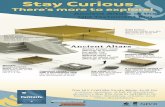

Defining the Afriscape through Ground Drawings and Street Altars

description

Transcript of Defining the Afriscape through Ground Drawings and Street Altars

Duane Deterville

Defining the Afriscape throughGround Drawings and Street Altars

A sense of agency among Black peopleacknowledges the authenticity of recombinantAfrican practices in the trans-Atlantic AfricanDiaspora, as well as the inPuence of the African Diasporic dis-cursive network on continental cultural practice and politics.1Le sacred ground drawings of Umbanda called pontos riscados,drawn to indicate the presence of a spirit or entity, are a richarea to position a discussion of an evolving African practice inthe Americas.2 Le ideograms contained in the drawings arefrequently based on Kongo and Yoruba cosmology, indicating aconnection to and contiguity with the spirituality of Africancontinental space. Ley also demonstrate the recombinantnature of African Diasporic cultural expression. Likewise, pretovelhos, or “old Blacks,” are manifestations of African Diasporicspirits that similarly express connections to Africa. Le thou-sands of names and types of these entities multiply, diversify,and grow as Umbanda develops. Ley represent the connectionto the dynamic agency of Africans in the Diaspora.

Le extreme cultural segregation that chattel slavery creat-ed insured the continuity of African cultural practices as a sur-vival tactic, while the imposition of European colonial languages

Duane Deterville 45

Figure 1 (top). The ponto riscado for Vovo Maria Conga do Congo (Grandma Maria

Conga of the Congo). Figure 2 (bottom). The Ki-Kongo cosmogram known as

Yowa or Dikenga.

44 Sightlines 2009

Maria Conga do Congo (Grandma Maria Conga of the Congo)is a good example of the ponto riscado broken into four sections(Og. 1). Le most interesting aspect of the pontos riscado forpreto velhos, however, is their apparent relationship to the Ki-Kongo cosmogram known as Yowa orDikenga.3Le cross with-in a circle is the most common representation of the cosmo-gram (Og. 2). Most importantly, the area below the horizon lineindicates kalunga or the land of the dead where the ancestorsdwell, and the horizon line itself is oQen represented as a bodyof water. Le ponto riscado forMaria Conga do Congo containsthree smaller crosses below the horizon line that represent the“. . . vibracao das almas” or “vibration of the souls.”4Lese cross-es must be represented below the horizon line in the ponto risca-do, and it is this element that ties them closely to the cosmolo-gy of Central African religions that manifest themselves in theDiaspora.5 Umbanda’s pontos riscados are a living practice thatdraws on ancient cosmology even as it evolves and recreatesitself in contemporary ritual and contemporary artistic practice.

Abdias do Nascimento and Casper Banjo

Abdias do Nascimento’s paintings are an excellent example ofhow ponto riscado ideograms inPuence contemporary Afri-Brazilian art. Nascimento’s creative eMorts are not primarily foraesthetic or formalist concerns; rather, his work explores arecombinant African spirituality and ethos that was, in hiswords, “exiled with my ancestors.”6 He paints orixas conPatedwith the names of contemporary people7 (Og. 3). Nascimentouses the ponto riscado ideograms as a powerful statement aboutthe dynamic relationship between African religion, politicalstruggle, and representational space. His paintings acknowl-

Duane Deterville 47

and religions has been the impetus for the idea that Africans inthe Americas are hybrid objects of Western construction. How-ever, operating from a theoretic lens that provides agency forBlack subjects under colonial conditions, I interpret the impactof Western language and culture as being inevitably Africanizedin some manner at this point of cultural change. In other words,those acts of cultural violence are rendered less harmful by self-determined Black subjects because, no matter what the mode ofcultural interaction, we are always already African.

Lis essay is a critical exploration of the ways contempo-rary Black artists use African iconography in their work. Leforms of pontos riscados are among the places that Africaniconography can be found. At the conclusion of this essay I pro-pose the use of iconography found in pontos riscados along withemerging Internet web-cast technology as a tool for veneratingthe dead victims of gun violence in the Black communities ofRio de Janeiro and Oakland. Lis essay concludes by engagingideas to use technology that adds Afrifuturism to my theoreticlens. Le use of internet web-casting expands the area of ritualspace to include virtual space along with metaphysical, AfricanContinental, and African Diasporic spaces to form what I callthe Afriscape. It is because I advocate for the model of willfulagency for African Diasporic subjects that I Ond this usage to bean authentic African cultural practice.

A brief explanation for one example of the form and syntaxused in pontos riscados is useful to understand the potential oftheir artistic uses. Le ideograms for the pretos velho entitiesusually contain a cross, which may be the circle of the pontoriscado sectioned into four parts or the Judeo-Christian crossthat is found in Catholic iconography.Le ponto riscado forVovo

46 Sightlines 2009

Figure 3. Abdias do Nascimento. Efrain Bocabalistico: Oxossi, Xango, Ogum.

Acrylic on Canvas. 1969.

48 Sightlines 2009

edge and represent both the living and the dead. He explainsthat, “In my painting I try to distinguish between those symbolsand myths that exist only as tradition and those that fulOll theneeds of our time and can open up perspectives for the future.”8

Nascimento emphasizes that his paintings use a contempo-rary practice to access the power of African spirituality for usein a secular context. Le future-focused concerns inherent inNascimento’s art practice relate it to Afrifuturism. I used a sim-ilar sensibility in my response to the violent killing of my friendCasper Banjo. Using the form of the ponto riscado ground draw-ing, I brought his image into a contemporary secular event.Contemporary secular rituals can be created anywhere in theAfriscape where visual subjects draw on similar cosmology forinspiration.Le mourning vigil for Oakland Black artist CasperBanjo in east Oakland on March 25th, 2008 is a primary exam-ple of the ponto riscado form in use outside of the Umbanda rit-ual that nevertheless carries the same attention to Kongo cos-mology and ancestor veneration. Seventy-one-year-old CasperBanjo was a highly respected Oakland printmaker and painter,whom Oakland police oNcer Tim Martin tragically killed onMarch 14th, 2008. On March 25th, 2008 a mourning vigil washeld in east Oakland near the site of elder Banjo’s death.

Seized with a need to both mourn and venerate the life ofmy friend Casper Banjo, I designed a ponto riscado for him.Lemost common theme in elder Banjo’s paintings and prints wasthe motif of a brick wall. Le walls were a representation of theurban Saint Louis environment in which Banjo spent part of hischildhood. In keeping with this element in his life, my designconsisted of a circle with a horizon line in the middle and abrick wall motif Olling the space (Og. 4). Le space below the

Duane Deterville 49

Duane Deterville 51

horizon line contained a simple drawing of an African banjostring instrument. Le outer circle was a reproduction of theKi-Kongo cosmogram with arrows moving in a counter-clock-wise direction as is common in its representation. Le banjoinstrument is an obvious representation of the “alma” or soul ofCasper Banjo, and it is located below the horizon line to indi-cate that he dwells in kalunga or the land of the ancestors. At themourning vigil, I drew the ponto riscado on the ground near thesite of Elder Banjo’s death and subsequent transition to being anancestor. Unable to endure the sadness of the event, I leQ imme-diately aQer executing the ground drawing. Le following day Ireceived the photographs of the ground drawing that the atten-dees had decorated with candles (Og. 5). I was told that atten-dees gathered around it in remembrance and veneration ofCasper Banjo’s contribution to the community.

As a result of the placement of Kongo ideograms in thespace of a communal event, this mourning vigil shares aNnitieswith Umbanda’s preto velho “gira,” or ritual, and African ances-tor veneration rituals. It is an example of the discursive net-works that can be created via the language of Kongo-rootedsigns and symbols related to the practice of creating pontosriscados. Lese practices have the potential of opening up dis-

50 Sightlines 2009

Figure 4 (opposite top). Duane Deterville. Casper Banjo Ponto Riscado Design.

Figure 5 (opposite bottom). Duane Deterville. Casper Banjo Ponto Riscado. East

Oakland. Photo by Wanda Sabir.

the body of literature preceding Dery’s description. However,Dery does observe that the tools used in Afri-Diasporic spiritu-al practices, “such as voodoo, hoodoo, santeria, mambo, andmacumba, function very much like the joysticks, Datagloves,Waldos, and Spaceballs used to control virtual realities. JeromeRothenberg would call them technologies of the sacred.”11

Taken a step further, the mojo bags of Louisianan Hoodoo,the patua of Afri-Brazilian Macumba, and the pontos riscadosground drawings of Umbanda can be understood as Afri-Diasporic hyperlinks to metaphysical forces embodied inKongo cosmology. Lese “technologies of the sacred” are evi-dence of how Africans in the Diaspora access the past and spec-ulative future simultaneously. Cultural critic and theorist GregTate underlines this notion when he says, “you can be backwardand forward-looking at the same time.”12 Le process of sam-pling employed in hip-hop is the most ubiquitous example ofthis sensibility and its application to the intersection betweentechnology and cultural expression. Le process of Ondingobscure, forgotten recordings and using them as the basis forpieces of music that are radically diMerent from the original isno doubt what lead Tate to say that “hip hop is ancestor wor-ship.”13 Tate’s statement is in keeping with perspectives onaccessing traditions from the past that are expressed in WestAfrican Akan philosophical ideas and embodied in the Adinkrasymbol of the Sankofa bird. Le Sankofa ideogram is graphical-ly illustrated by a long-necked bird with its head facing back-wards. It represents the idea that there is no taboo in returningto retrieve something that you may have lost, nor using it in thepresent in order to build a new future.14

Le notion of an ongoing ritual discourse—religious or

Duane Deterville 53

cursive networks across African Diasporic lines that can pro-vide a conduit for mourning and healing in the face of rampantoppressive gun violence in Black communities. In order to openthose networks, Black culture workers have the opportunity toactivate the spaces of secular mourning rituals with willfulfuture-focused visionary actuation.

Afrifuturism or The Future Blackwards

Lere is a rich legacy of Afri-Diasporic intellectuals who drawon imaginative, creative vision to imagine new futures for Blackfolks without losing sight of contemporary relevance. Lesefuture-minded intellectuals engage in cultural expressions thatdraw upon components of African ethos and engage it with thedeliberate intention to create recombinant African culturalexpression in the Diaspora.

Afrifuturism is my preferred spelling for what theoristMark Dery called “Afrofuturism.”9 Dery deOnes Afrifuturism as:

speculative Cction that treats African American themes andaddresses African American concerns in the context of twen-tieth-century technoculture—and, more generally, AfricanAmerican signiCcation that appropriates images of technolo-gy and a prosthetically enhanced future.10

Dery’s descriptions of Afrifuturism omit the literature ofMartin Delaney and George Schuyler (among others) whowrote about Black identity in speculative futures. Lis avoidsthe Black intellectual contribution to Afrifuturism prior to theappearance of Black characters in sci-O. Afrifuturism’s historicengagement with Pan-Africanism and a desire to transcendcolonialist boundaries is lost if these texts are not considered in

52 Sightlines 2009

terms acknowledge how diMerent the landscape looks depend-ing on what position we occupy in it.

I use the term Afriscape to underscore the contiguity ofAfrican culture, as it acknowledges commonality viewed fromvarying subjective lenses. However, I diMer from Appadurai inmy reasoning for the usage because my concern is for how theterm deOnes cultural cohesiveness among African people ratherthan emphasizing debilitating disjuncture.Le Afriscape is syn-onymous with Africa. It encompasses both Africa and its dias-pora regardless of geographic location. Any location thatAfrican cultural ethos is found is where the deterritorialized,ever-changing horizons of the Afriscape can be mapped. Liscultural cartography renders all these locales equidistant. Africashould not be deOned narrowly in terms of geography but moreimportantly as a cultural history that encompasses and tran-scends nation-state boundaries. Along those lines I deOne Blackpeople as subjects embodying the inOnitely malleable culturalethos of peoples descended from and ascending to an Africancontiguous history.

Blackness is the cultural ethos of African civilizations. Itsvery nature deOes Oxity and enables it to manifest across largeexpanses of time and space. Blackness is a perpetual motionmechanism that uses ancestor veneration as the motor of itsontology. Lis Black ontological process functions through theretrieval of an endless myriad of African practices, histories,and rituals in order to reconOgure them for contemporaryapplication. African and Black are signiOers for the same sub-ject viewed from diMerent angles. In most contexts they areidentical and synonymous. Ley are culturally constitutedthrough a contiguity of histories, practices, and willful imagi-

Duane Deterville 55

secular—with ancestors is in fact an advanced Afri-Diasporicsurvival tactic that protects African cultural ethos fromEurocentric hegemony. Culture theorist Tricia Rose statesplainly in her interview with Mark Dery, “If you’re going toimagine yourself in the future, you have to imagine whereyou’ve come from; ancestor worship in black culture is a way ofcountering a historical erasure.”15

Defining the Afriscape

To this discussion about the past, I add that ancestor venerationin secular or religious settings is the primary force of AfricanDiasporic subjectivity and that secular manifestations of ances-tor veneration, such as hip-hop, are in fact a recombinantAfrican ontology in the Americas that draws upon conceptspredating the existence of the colonial “new world.” Poet,activist Amiri Baraka observes in his prescient 1971 Afrifuturistessay Technology and Ethos that “the actual beginnings of ourexpression are post Western (just as they are truly preWestern).”16 Le act of drawing on Continental African cultur-al ethos, contemporary technology, and artistic actuation iswhat creates a self-determined, representational space thatforms what I call the Afriscape. Le Afriscape maps the deter-ritorialized cultural presence of Black/African subjects any-where in the world. Le term Afriscape draws on concepts cre-ated by social anthropologist and cultural theorist ArjunAppadurai.17 Appadurai proposes Ove aspects of global culturalPows that he says stem from disjunctures involving culture, pol-itics, and economies. Among these aspects of cultural Pows areethnoscapes and technoscapes.18 Le advantage to using termsthat analogize varying concepts to landscapes is that these

54 Sightlines 2009

tional space that function in similar ways to the notions ofEgungun. Le living and historical Ogures are conPated withsupernatural African spirits or venerated as ancestral spirits.Similarly, in the Yoruba belief systems, the ancestors are presentwith the living and can be mediators between the material andspiritual worlds.

A variation on this practice is the method of conPating his-torical Ogures with orishas in the way that African Americanartist Kerry James Marshall does with his 1991 painting titledNat Shango (Aunder)20 (Og. 6). Le painting depicts a standingBlack, male Ogure with two single-headed axes, one in eachhand, with several collaged heads of white women painted withyellow Olling the upper third of the painting. Le presence oftwo axes implies the double-headed axe symbol for Shango. Lehistoric Ogure of Nat Turner, who led the most famous slaverebellion in United States history, is merged with the powerfulimage of the Yoruba deity of justice, retribution, and thunder.Not only does it singularly imply that this famously brutalrebellion was a manifestation of justice, it also subverts thenotion that Nat Turner acted under the inPuence of theEuropean, Judeo-Christian teaching that he espoused as apreacher. Marshall’s painting reclaims this historical event andreinscribes it with a narrative that claims autonomy of thoughtand action motivated by African belief systems in the peoplewho executed the rebellion. In addition, when Marshall super-imposes Shango with Nat Turner, he further insinuates theYoruba notion that long dead ancestors are mediators betweenthe living and the supernatural orishas. Marshall claims Blackhistorical, representational space and Black cultural space thatdelineates two geographic points in the Afriscape; the location

Duane Deterville 57

nations that are never static but are positioned at the epicenterof the Afriscape in constant forward and backward symbioticmotion rePective of the Akan philosophical notion of Sankofa.

Afri-Diasporic Artists, Representational Space, andAncestor Veneration

Le process and method of venerating ancestors—in secular orreligious contexts—are probably the most common spiritualpractices among Black people across the Afriscape.Le practiceof remembering the dead, invoking their names, invoking theirimages, and channeling their presence in spirit possession isfound both on the continent of Africa and in its wide-rangingDiaspora. Le value of ancestor veneration lies in the powerthat it holds to bring the past into the present in new ways thatcan create a communal, representational space that facilitatescommunal healing. Both established international contempo-rary artists and cultural workers whose impact is purely localcreate artifacts that access ancestor veneration in some way.Lenotion that the dead still guide the living is a powerful tool inhealing Black, urban communities that have organically devel-oped secular rituals for venerating the dead through the cre-ation of street altars. Le West African Yoruba word Egun orEgungun is commonly used for the practice of venerating thedead in African Diasporic religious systems such as Afri-CubanLucumi, Afri-Cuban Palo, and Afri-Brazilian Candomble.19

Afri-Diasporic artists such as Nascimento (born in 1914)and Kerry James Marshall (born in 1955) are examples of twodiMerent generations that have created visual art that accessesthe power of African spirituality. By accessing African spiritual-ity in their work, Black artists open up avenues of representa-

56 Sightlines 2009

Figure 6. Kerry James Marshall, acrylic on canvas with paper collage. 74 x 55".

Nat Turner (Shango), 1991.

58 Sightlines 2009

of Shango with the Yoruba in West Africa and the location of ahistoric slave rebellion in the state of Virginia are brought intothe present through the medium of a contemporary painting.

Le role of the artist in contemporary, secular ancestorveneration varies widely in the types of cultural expressionused. I am using the label “artist” here in the broadest sense toinclude those creative projects that are not considered in thesame ways that western art projects are considered. An artist isa participant in the creation of vernacular street altars inOakland or a painter of the walls of Vodun ritual spaces inHaiti. Artists are consistently a key element in the creation ofAfri-Diasporic ritual space.

Le late Haitian painter and Vodou Houngan Andre Pierreis one example of the multiple roles that artists play in the cre-ation of ritual space in the African Diaspora. I visited AndrePierre’s compound and outdoor painting studio in 2002. Pierre’smultiple roles included not only being recognized as a VodouHoungan in his community but also as an internationally rec-ognized painter of Vodou rituals and spirits called loas (Og. 7).His paintings are not just illustrations of the Vodou rituals butconsecrated religious icons. In a catalog published in 1978 byLe Brooklyn Museum for an exhibition titled Haitian Art, UteStebich noted,

Pierre sees no contradiction between painting and his priest-hood. On the contrary, since every piece is devoted to thespirit’s glory, he understands his art as a principal means ofdemonstrating his reverence. Each picture is presented to,approved and consecrated by the divinities. Ais ceremonyturns his paintings into religious icons.21

Duane Deterville 59

Duane Deterville 61

Figure 7. Andre Pierre, Oil on canvas. 42x24", Baron Samedi, 1977.Andre Pierre understood his paintings to be agents of hispriesthood in the secular world of art collectors. He used themto send the power of the loas into the world. An additionaldimension of Pierre’s role as a Vodou priest is that he paints thewalls of his ritual space with sacred imagery. He expands theborders of his ritual space through his visionary artistic expres-sion. He aMects the ritual space through control of the visualOeld not just within the conOnes of his Vodou Houmfour butoutside of it when his consecrated paintings make their waythrough the secular, western art collector’s world. Le move-ment of his consecrated ritual images in the form of paintings,beyond the Vodou rituals that they depict, empowers them tocreate Afri-Diasporic representational space away from thepoint on the Afriscape that they were created.

Lese artists make representational spaces that acknowledgethe presence of spirit forces beyond thematerial world.Ley pur-posely use the power of African ritual iconography and imageryto ignite a historical space, in the case of Kerry James Marshall’spainting Nat Shango, and the spaces outside of the Vodou cere-monies, in the case of Andre Pierre’s paintings. Paintings by theseBlack artists use a diMerent value system and purpose than thatwhich is usually ascribed to the tradition of western painting.Abdias do Nascimento not only emphasizes the power of hisimagery to transcend the colonial nation-state boundaries but alsohis belief that his images become a conduit of non-verbal com-munication between the living and the dead. Nascimento says,

In the United States for instance I was very impressed by peo-ple who viewed my paintings and started crying. . . . my artwas used as a way to express feelings between people who arealive and other people who are dead.22

60 Sightlines 2009

Collective Healing: A Proposal for an AfrifuturistIntervention

“Ae real problem is, do we have time enough to get at thenihilism—the collapse of civic attentions that has gone on in thiscountry, where blacks are allowed to sink into poverty and shooteach other—drug wars—while the rest of America commutesindiBerently to the suburbs?” —Robert Farris Aompson25

As one of the most prominent scholars of trans-Atlantic Africanculture, Robert Farris Lompson’s statement is an indicationthat the study of Afri-Diasporic cultures should not be solelyconcerned with unearthing or theorizing connections betweenAfrican cultures. My concern, along withLompson’s, is for howthese connections aMect the representational space of Black peo-ple, the contemporary inhabitants of the Afriscape. Le traumaof gun violence in Black communities has produced the practiceof turning sidewalk space into secular ritual place. Le mannerin which Black people in these communities respond to thesetragic events by creating street altars to those who have beenslain is an indication that even in the midst of great trauma thereis still a sense of agency and a willingness to venerate the dead.Lese altars are signiOcant because they reinscribe the evolvingAfrican presence in Afri-Diasporic Black identity that is rePec-tive of African sensibilities towards ancestor veneration. Addi-tionally, they are important because they evidence the fact thatcontemporary vernacular artists still express these sensibilities.

Altars that conspicuously occupy ground space on streetcorners and sidewalks in response to the presence of death inBlack communities underscore the continual presence ofKongo rooted signs in the African Diaspora. Le common

Duane Deterville 63

Nascimento refers here to the way in which his paintingstranscend the colonial language barriers of English andPortuguese. Similar to the manner that Andre Pierre viewed hisartistic practice as part of his spiritual practice, Nascimentosees no diMerence between his contemporary painting practiceand the creation of Umbanda’s ponto riscado ritual grounddrawings.23

The ground drawing that I created in East Oakland atthe mourning vigil for Casper Banjo carries a similar sensi-bility because my intention was not as much to create animage to be aesthetically evaluated, but to respond to a trau-matic event in a way meant to go beyond aesthetics in orderto access a collective emotional response. The collectiveresponse to the ground drawing was perfectly appropriate.My intention is to engage the visual subjects that inhabit theAfriscape directly. I am not analyzing visual events at a dis-tance through critical theory alone. I enter the ritual theaterof the visual event and become one of the visual subjects. Inher essay Terra Infirma: Geography’s Visual Culture, curatorand writer Irit Rogoff remarks, “. . . the perspectives that Iwould like to try to represent, the critical analysis of visualculture, would want to do everything to avoid a discoursewhich perceives itself as ‘speaking about’ and shift towards adiscourse of ‘speaking to’…in claiming and retelling the nar-ratives (‘speaking to’) we alter the very structures by whichwe organize and inhabit culture.”24 I agree with Rogoff ’scomments, and I propose to continue the method of speak-ing to Afri-Diasporic subjects in the manner of anAfrifuturist who proposes new narratives or ways for Blacksubjects to inhabit new futures.

62 Sightlines 2009

particularly fertile ground for projects that directly engage thecommunity in healing strategies. Le predominantly Blackcommunities in East and West Oakland have recently respond-ed to the prevalent gun violence by creating eNgies that repre-sent the dead victims of shootings (Og. 8). Lese eNgies, mostfrequently representing the likeness of a young Black man, areerected in the space that the victim died. Lese eNgies repre-sent the latest evolution of an ongoing practice of veneration forthe dead that turns place into secular ritual space. Le emer-gence of the vernacular artists who erect these eNgies are anindication that there is an open acceptance of new, evolvingforms of venerating the dead in the space of the public street. Iobserved that the street is more recognized by the Black com-munity as the place holding the spirit of those young men lostto gun violence as opposed to the rariOed spaces of galleries,mortuaries, or churches where there are more customs andexpectations imposed on claiming representational space.

I observed similar conditions of gun violence in my Oeld-work while visiting the Jacarezinho favela of Rio de Janeiro,Brazil in August of 2008. Jacarezinho’s impoverished communi-ty’s victims were predominantly young Black men killed in vio-lence associated with the presence of the drug trade. Using theAfrifuturist visionary lens that engages technology, in additionto seeking ways of willfully engaging and making connectionsacross Afri-Diasporic lines with other inhabitants of theAfriscape, I propose a new method for venerating the dead.Lecommunity’s reaction to the ground drawing that I created forCasper Banjo in East Oakland indicates that there is acceptancefor the notion of the ground drawing in the open context of thestreet. Building upon people’s reactions and the openness of the

Duane Deterville 65

denominators in Kongo symbols serve as signposts that mapthe Afriscape. An altar constructed communally by mournerswho knew the dead victim of the gun violence typically consistsof Powers, stuMed animals, dolls, balloons, and prayer candles.But most prominent and common are glass bottles that aremostly, but not exclusively, liquor bottles. Lese bottles areanother manifestation of the practice found in Mississippi,Louisiana, and South Carolina of using bottles on gravesitesand trees as ways of variously protecting the houses of the liv-ing against the return of evil spirits and also preventing the wor-thy traits or talents of the deceased from being lost in the void.Le presence of plates or bottles on trees over Central AfricanKongo gravesites, according toLompson, means “not the end,”or “death will not end our Oght.”

According to Lompson, “Afro-American bottle trees arefugitive specters from a graveyard realm, just as bottle-linedburials are horizontal bottle trees.”26 I agree with Lompson’sassertion and add that urban street altars are to bottle trees whatUrban Blues music is to Delta Blues—a southern, rural Kongofugitive specter Onding its way into the city. In Oakland thepresence of bottle glass on urban concrete that is still hot withviolent death is the innate, culturally constituted practice of Blackfolks that is used to cool a space from the return of destructivespirits. Le presence of the bottles also alludes to the custom ofpouring water or alcohol as libations in honor of spirits and ances-tors. Lis explains the presence of bottle glass on Vodun altarsin Haiti. Ley are part of the recurring presence of Kongo signs,form, and syntax in the common lives of Afri-Diasporic subjects.

Le presence of these street altars and the creation of ver-nacular street art in Oakland that venerates ancestors make a

64 Sightlines 2009

Figure 8. Unidentified Artist. Effigy located in West Oakland. 2007.

66 Sightlines 2009

secular ritual space of an Oakland urban street, I plan to createan event that connects the creation of ground drawings byartists for people who have fallen to gun violence via intercon-tinental internet webcast. Le creation of ground drawings onthe street by artists venerating the recently killed inhabitants ofJacarezinho favela in Brazil along with East and West Oaklandwill create a unique Afri-Diasporic secular ritual space.Le formand syntax of the ponto riscado ground drawing is alreadyfamiliar to most inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro, and the work ofAbdias do Nascimento is an indication that their usage in secularspaces is not unheard of.Le images representing the recent deadin the secular ritual space of two local urban streets will be con-nected in a way that widens the ritual space to include cyberspace.

Le presence of others within the context of a mourningritual is one powerful element in the healing process. Oakland’sBlack neighborhoods deal with trauma from the rampant lossof community members through the creation of communalaltars. Le act of creating the altar reinforces the idea that thereis still community, that there is emotional support for the fam-ily of the victims, and that the dead are in some way still pres-ent with us. If these communities—Jacarezinho and Oakland—experienced an even larger representational space that connectsthem to other Afri-Diasporic peoples with a situational com-monality, such a representational space holds the potential tobring an even deeper sense of community, empathy, and subse-quent emotional support.

Le ultimate goal is to transcend nation-state boundariesin addition to the colonial language barriers of Portuguese andEnglish in a way that reinscribes the African presence in newways across the Afriscape.

Duane Deterville 67

Press, 1997). 233.Le Akan are an ethnic group residing in Ghana.Ley arerenowned for having developed a corpus of symbols called adinkra whichcorrespond to proverbs that explain philosophical ideas practiced by theirgroup. Gyekye explains the meaning of Sankofa.

15 Tricia Rose, interview by Dery in “Black to the Future: Interviews withSamuel R. Delaney, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose.” 215

16 (Leroi Jones) Imamu Amiri Baraka, “Technology and Ethos,” Amistad 2Writings on Black History and Culture, no. 2 (1971). 321. Baraka’s essay pre-dates Mark Dery’s Afrofuturist interviews by two decades and engages theidea of African cultural expression’s relationship to technology beforeDery’s.

17 Arjun Appadurai,Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization,ed. Dilip Gaonkar and Benjamin lee, 1st ed., vol. 1, Public Worlds(Minneapolis London: University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

18 Ibid. 34.19 J. Omosade Awolalu, Yoruba Beliefs & SacriCcial Rites, First ed. (Brooklyn:

Althelia Henrietta Press, Inc. Publishing in the Name of Orunmila, 1996).65–66.

20 Kerry JamesMarshall, Terrie Sultan, Arthur Jafa,Kerry James Marshall, Firsted. (New York Harry N. Abrams, 2000). 11, 53.

21 Ute Stebich, Haitian Art, First ed. (Brooklyn: Le Brooklyn Museum,Division of Publications and Marketing Services, 1978). 167.

22 Abdias Nascimento, in conversation with the author. (Rio De Janeiro:Unpublished, 2008), Digital recording.

23 Ibid.24 Irit RogoM, Terra InCrma: Geography’s Visual Culture, First ed. (London and

New York: Routledge, 2000). 3225 Robert Farris Lompson, interview by Donald Cosentino in African Arts

25, No. 4, no. 100 (1992). 59.26 Robert Farris Lompson, Flash of the Spirit, 1st ed. (New York: Random

House, 1983). 144–145.

Duane Deterville 69

Notes

1 J. Lorand Matory, “Afro-Atlantic Culture: On the Live Dialogue betweenAfrica and the Americas,” in Africana: the Encyclopedia of the African andAfrican American Experience, ed. Jr. Kwame Anthony Appiah and HenryLouis Gates (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 1999).

2 Diana DeGroat Brown, Umbanda Religion and Politics in Brazil, 2nd ed.(New York: Columbia University Press, 1994; reprint, Columbia UniversityPress Morningside Edition). Pontos riscados is pronounced “pawn-toes his-cah-dohs.”

3 Kimbwandende Kia Bunseki Fu-Kiau, African Cosmology of the BantuCongo, 2nd ed. (Brooklyn: Athelia Henrietta Press, 2001).

4 Mae Fatima Damas, in conversation with the author, Rio De Janiero, 2008,digital audio.

5 Ibid. Damas indicated that if the crosses are not represented below the hori-zon line she would question the authenticity of the ponto riscado.

6 Abdias Nascimento, “Art and the Orishas,” in Abdias Nascimento 90 Years-Living Memory, ed. Elisa Larkin Nascimento (Rio De Janeiro: IPEAFRO,2006).

7 Orixas are West African gods found in primarily Yoruba-rooted religions.8 Abdias do Nascimento and Elisa Larkin Nascimento, Africans in Brazil

(New Jersey: Africa World Press Inc., 1992). 549 Mark Dery, “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delaney, Greg

Tate, and Tricia Rose,” in Flame Wars: Ae Discourse of Cyberculture, ed.Mark Dery (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1994). 180. I pre-fer the spelling “Afrifuturism” because there is no “O” in Africa, and it is mysuspicion that the preOx “Afro” is merely a Pawed dialectical response to thepreOx Euro.

10 Ibid. 18011 Dery, “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delaney, Greg Tate,

and Tricia Rose.”12 Greg Tate, interview by Dery in “Black to the Future: Interviews with

Samuel R. Delaney, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose.”etc. Ibid. 21113 Greg Tate, Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America, First

ed. (New York London Toronto Sydney Tokyo Singapore: Fireside Simonand Schuster, 1992). 130

14 Kwame Gyekye, Tradition and Modernity: Philosophical ReDections on theAfrican Experience, First ed. (New York and Oxford: Oxford University

68 Sightlines 2009

![Umbanda Altars and Offerings Found in Niterói, Brazil · Microsoft PowerPoint - Candomble-Umbanda - altars as art [Compatibility Mode] Author: BRAVO Created Date: 4/26/2010 9:25:20](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5f023dfb7e708231d40348bc/umbanda-altars-and-offerings-found-in-niteri-brazil-microsoft-powerpoint-candomble-umbanda.jpg)