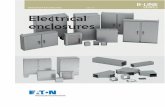

De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

-

Upload

yanis-margaris -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

1/14

Enclosures, Commons and the Outside.

Massimo De Angelis1

I

When we reflect on the myriad of communities struggles taking place aroundthe world for water, electricity, land, access to social wealth, life and dignity,one cannot but feel that the relational and productive practices giving life andshape to these struggles give rise to values and modes of doing and relatingin social co-production (shortly, value practices). Not only, but these valuepractices appear to be outside correspondent value practices and modes ofdoing and relating that belong to capital. The outside with respect to thecapitalist mode of production is a problematic that we must confront withsome urgency, if we want to push our debate on alternatives on a plane that

helps us to inform, decode, and intensify the web of connections of strugglingpractices.

The urgency can also be detected in the desire that many activists involved inthe many local ripples and trans-local rivers of the global justice andsolidarity movement have to run away from the claustrophobic, devious andecumenic embrace attempted by the agents of neoliberal governance. Listenfor example to Paul Wolfowitz, one of the inspirer of the butchery of Iraqpeople, and now respected president of the World Bank. In its first speech atthe annual IMF and WB meeting last September 2005, he said:

we meet today in an extraordinary moment in history. There has neverbeen a more urgent need for results in the fight against poverty. Therehas never been a stronger call for action from the global community. Thenight before the G8 summit in Gleneagles, I joined (sic) 50000 youngpeople gathered in a soccer field in Edinburgh to the last of the live-aidconcert. The weather was gloomy, but the rain did not dampen theenthusiasm of the crowd. All eyes was riveted on the man who appearon the giant video screens, the father of South Africa freedom. And thecrowd roared with approval when Nelson Mandela summed us to anew struggle, the calling of our time: to make poverty history.(Wolfowitz 2005)

In the words of the World Bank president, the fight against poverty is aspectacular event, uniting neoliberal supranational institutions and neoliberalnational governments marching together with youth wearing sweatshop-produced rubber bands and rock stars with cool sunglasses announcing to theCNN audiences that good governance is indeed the practical solution to

1

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

2/14

such a calamity.2As poverty is no longer a concrete condition of life andstruggle, it is turned into an abstract enemy, an outside that is supposed to befought with correspondent abstract policies that is, to recite a recent world

bank document assessing South Africa investment climate, macroeconomicsand regulatory policies; the security of property rights and the rules of law;and the quality of supporting institutions such as physical and financialinfrastructure. (World Bank 2005: 5) With the definition of this abstractoutside, concrete struggles of the poors that turn poverty into conditions ofproduction of community, social cooperation and dignity, can be locallycriminalised: after all they threaten macroeconomic stability, they threatenproperty rights and the rule of laws, and they threaten the roles ofinfrastructures qua vehicle of capital accumulation, demanding instead thatthey are devoted to the reproduction of needs of communities. With theproclaiming of poverty as an outside to struggle against, Paul Wolfowitz andthe discourse promoted by the institution he presides, can declare war to thepoors, and kill threebirds with a stone: first, continue to promote neoliberal

policies that reproduce the poors as poors, through further enclosures and thepromotion of disciplinary markets and their homeostatic mechanisms;second, persevering on the creation of a context in which the poors strugglesare criminalised whenever they oppose neoliberal discourse and reclaimcommons; and, third, divide the struggling body into goods and bads, thegood ones being the responsible movements holding hands with PaulWolfowitz and the likes, and the others the irresponsible rest of us. The

basis of neoliberal governance depends on games and selecting principles likethese.3

Listen instead to critical ethnographic accounts of poors struggles.

This was another defining moment for the struggle of the flat dwellers[in Chatsworth, SA]. Indian women had stood in the line of fire in orderto protect an African family who had no mother. If they had lost, theMhlongos would have been forced into the nearby bush. The council,

2

!!"# $$ $$ %

& $$ ' ( ) ** +# # # , - # )& ' ( . .'/ 0

1 '/ 2 3 . (4 + (4 5 12 6 7 8*8 4 # 8+ 9 8 1:4 $. ./ ' 1, ( '/ )0

+ , ) , %;;

3 +

# : 8

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

3/14

too, had shown its hand. For them the broader issues of the sense ofbuilding non-racial communities from the bottom up meant nothing.The fact that Mhlongo was respected by the community and wasworking hard as a mechanic to give his family a chance in life wasequally irrelevant. The council was a debt collector, fighting on moralterms. Their sense of morality was frighteningly clear. Mhlongo was anundesirable because he got in the way of their collection of (apartheids)debts. (Desai 2002: 53)

Also here we can envisage an implicit problematisation of the outside, buthere the outside presents itself in a more complex dimension. It is not posited

by abstract principles, but it is constituted as concrete and sensuous process,in which outsideness and correspondent reclaiming of otherness emergesout of the refusal of an outside measure, an outside value practice and it isreclaimed as a quality of a living relational practice. In the constitution of thisoutside to capitals measure we find the poors way to make poverty

history, by beginning, again and again and again, their own history. Theoutside here, shall we call it with a provocation, our outside, emerges andbecomes visible on thefrontline. This is the place of the clash against the outthere imposing its rules, as when opposition is deployed against the debtcollector who comes to knock at the door with a riffle butt or, at a differentscale, against the government and corporate managers conveying themessages that global market signals have decree the ruin of an industry andcorrespondent communities. The outside created by struggles is an outsidethe emerges from within, a social space created by virtue of creating relationalpatterns that are other than and incompatible with the relational practices ofcapital. This is our outside that is the realm of value practices outside those of

capital and, indeed, clashing with it. The value practice of Indian womendefending an Africas family (and thus contributing to the creation of acommon and the reformulation of identities)4versus the value practices of adebt collector evicting another African family in the name of respect ofproperty, rule of law and contract.

4 + &

0 :> + +

% )8 # ? * & 8 + + ( 1B +#

A' 8# > -

0 ,

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

4/14

Ouroutside is a process of becoming other than capital, and thus presents itselfas a barrier that the boundless process of accumulation and, in the firstinstance, processes of enclosures, must seek to overcome5. It goes withoutsaying that this outside is contingent and contextual, since it emerges fromconcrete struggles and concrete relating subjectivities. And it is also obvious,that the emergence of this outside is not a guarantee of its duration andreproduction. The point I am making is only this: Our outside is the realm ofthe production of commons. To this we will return in section III.

II

A brief review of some of the conceptions of the outside within radicalliterature reveals both the strength with which the many traditions havecharacterised capitals relation to the outside, but at the same time theweakness within which the processes of constitution of our outside, has

been brought into the spotlight of the problematisation.

In her classic text, for Rosa Luxemburg the outside presents itself as the pre-capitalist space that capital needs to colonise to face crises of underconsumption. In her account, capital accumulation has a twofold character.On one hand, commodities markets and the production processes in whichsurplus value is produced. Here, in classic fashion, accumulation is a purelyeconomic process, with its most important phase a transaction between thecapitalist and wage labourer. On the other hand,

accumulation of capital concerns the relations between capitalism andthe non-capitalist modes of production which starts making their

appearance on the international stage. Its predominant methods arecolonial policy, an international loan systema policy of spheres of

interestand war. Force, fraud, oppression, looting are openlydisplayed without any attempt at concealment, and it requires an effortto discover within this tangle of political violence and contests of powerthe stern laws of the economic process (Luxemburg 1968).

Although, we cannot avoid to problematise the classical division of these twosides of accumulation into economic and political, and we are certainlyaware of the difficulties of the under consumption argument at the basis ofcrises (giving for example no role to credit), Rosa Luxemburg contribution is

crucial in pointing out at the continuouscharacter of primitiveaccumulation.6

5? #

: 8

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

5/14

The work of Harold Wolpe (1972), in a Luxemburgs fashion, envisages theoutside as the precapitalist mode of production that came to an end in SouthAfrica with industrialization and apartheid. Arguing that segregation andapartheid were two distinct phases of capitalist regimes in South Africa,Wolpe was able to clarify the role of the reserves in the pre-apartheid regimeas a pre-capitalist outside which was instrumental to reducing the cost ofthe reproduction of labour time. This came to an end with the process ofimpoverishment of the reserves due to migration of adult population andunderinvestment, couple to the expropriation of land. The apartheid regimetherefore, with escalating element of coercion, had to be decoded as acapitalist strategy of subordination of increasingly rebellious urban blackworking class. With apartheid, in other words, we move from a dual, to asingle mode of production. Hence ultimately, in Wolpes work, at the end ofthis historical process there seem to be no outside to the capitalist mode ofproduction, at least in South Africa.

From a completely different perspective, and one which is less equipped toproblematise and account for the hierarchies being reproduced within theglobal multitudes, Hardt and Negri (2000; 2004) reach the same conclusionand state it explicitly: the outside is part of the dialectic inside-outside

belonging to modernity, while in post-modernity and Empire, there is nooutside. One could read this in terms of the fact that in the current phase thereis no outside to capitalist relations of production, that is relations betweeninside-outside of a particular nature, with the pervasiveness of the markets

brought by neoliberal globalization processes. But this interpretation is alsoproblematic once we see that in Hardt and Negri the paradigmatic process of

capitalist relations of production, the processes of measuring human activityfrom the outside of the direct producers and turning it into work, i.e. the lawof value, is supposedly coming to an end thanks to immaterial labour, or, atleast, this is supposed to be the tendency.7As it has been argued, this is farfrom the case, and when the issue of capitals measure is brought back totheoretical investigation (as it applies not only to communities facingenclosures, but also to both waged material and immaterial labour), then

7. + # +

+ # )+ , ) / , #

) % 00+ ,

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

6/14

we can account for the reproduction and hierarchy as it emerges from theongoing disciplinary processes of the market.8

I will indulge now a bit more extensively to discuss David Harvey (2003). Inthis book he builds on Luxemburg position, and argues that the outside is theobject of accumulation by dispossession that capital needs in order toovercome crises of overproduction, rather than of under consumption. In hisview, what accumulation by dispossession does is to release a set of assets(including labour power) at very low (and in some instances zero) cost.Overaccumulated capital can seize hold of such assets and immediately turnthem to profitable use. (Harvey 2003: 149) The outside thus is soon to beinternalised by capitals loops which, benefiting from lower costs, willovercome the overaccumulation crisis until the next round of enclosures isrequired.

However, as pointed in different ways by Gillian Hart (2002; 2005), Sharad

Chari (2005) and George Caffentzis (2002), there is no guarantee thatfollowing dispossession the released labour power will find employment,hence means of reproduction, in the capitals circuits. This means thatenclosures always put on the agenda the problematic of social reproductionand the struggle around it. The outside thus turns from the object ofexpropriation into, to use Charis term, the detritus, which I understand to bea space in which the problematic of social reproduction is uniquely in thehands of the dispossessed, and dramatically depends on the effectiveness,organisational reach and communal constitution of their struggles and abilityto reclaim and constitute commons. The problematisation of this detritus, thestruggles emerging therein, is hardly present in Harveys framework, a part

from some scant references to the fact that accumulation by dispossessionprovoke community struggles.

The same apply with respect to the relational patterns between the conatus ofself-preservation of these communities in struggle and the conatus of self-preservation of capital9. So for example, Hart (2002; 2005) point out that we

8 +

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

7/14

should not see dispossession from the land as necessary condition forrapid industrial accumulation, or at least not within the same locality. As heranalysis of Taiwanese investments in South Africa argues, industrialisation inTaiwan was an unintended consequence of redistributive land reforms in thelate 1940s and early 1950s that operated as a social wage and became later theprecondition for Taiwan capitals investment into South Africa. By the time inthe 1980s wage pressures built in Taiwan, Taiwanese capitalists could find inSouth Africa a welcoming condition. Not only the apartheid regime wasproviding massive subsidies for national and international investors to locatein racialized industrial decentralised areas like Ladysmith-Ezakheni, but themillion of black South African expropriated of land in the previous years andpacked in townships in rural areas provided an opportunity for investmentfor labour-intensive production techniques and labor practices that will later

become socially explosive.

All these point to what I think is a theoretical weakness in Harveys turning of

the problematic of enclosures into one of accumulation by dispossession.This term, although evocative of the horrors of ripping apart communities,expropriating land and other means of life, is ultimately theoretically weak,since it posits dispossession as a meansof accumulation, rather than as whataccumulation is all about. Indeed, in the context of accumulation of whichboth continuous (and spatialised) enclosures and market disciplinaryprocesses are two constituent moments, separation of producers and means ofproduction means essentially that the objective conditions of living labourappear as separated, independent values opposite living labour capacity assubjective being, which therefore appears to them only as a value of anotherkind (Marx 1858: 461). In an office or factory, in a neighbourhood of the

Global South threatened by mass eviction or in the Northern welfare claimantoffice playing with single mothers livelihoods if they do not accept low paidjobs, the many subjects to capitals measure are at the receiving end ofstrategies that attempt to channel their life activities according to the prioritiesof this heteronymous measure that define for them what, how, how muchand when to exercise their powers (i.e. that turn their activities into labourfor capital). What is common to all moments of accumulation as social relationis a measure of things, that traditional Marxism has conceptualised in termsof the law of value, but that in so doing has fetished as purely anobjective law and not as an objectivity that is continuously contested bysubjects in struggles who posit other measures of things outsidethose of

capital.10

+)

10- 0 -

- + # # ) 10,

-# # 10# # )+, # # & # ) *) )

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

8/14

The extent to whichcapitals measure of things takes over the lives andpractices of subjects, that is, the extent to whichtheir livelihoods is dependent onplaying the games that the disciplinary mechanisms of the markets demandfrom them, then dispossession occur. The extraction of surplus labour andcorrespondent surplus value is only one side of the occurringdispossession. The other is the detritusinscribed in the bodies and in theirenvironments by the exercise of capitals measure on the doing of the social

body, and their life activity. This detritus that is around the subjects andinside subjects, help us to read dispossession not as an occurrence out there,

but as a condition of life practices coupled to a variety of degrees and atdifferent level of the wage hierarchy to capitals circuits.

The problematic of the outside has always been ambiguous in the radicalliterature that has addressed it whether implicitly or explicitly. On the onehand, capitals own revolution depends on the overcoming of conditions

that, in given contexts and scales, are not suitable to accumulation, henceoutside its value practices. This overcoming of conditions may well besimply the coupling of circuits of pre-capitalist production to circuits ofcapital (as discussed for example in Wolpes brillant work on articulations ofmodes of production). Or the destruction of these pre-capitalistcommunities by the enclosures of land and other resources, as Marxsdiscussion of primitive accumulation points out. On the other, radicalthinking is supposedly entirely devoted to the problematisation and searchfor an outside to the capitalist mode of production: what is, in traditionalterms, the symbolic value of revolution but this great event delivering uswith a field of social relations outside those of capitalism?

In all the diverse approaches I have reviewed, I have difficulty to detect anytension to overcoming this ambiguity. Whether it is an outside that come toan end due to the increasing dependence on the wage by the proletariat(Wolpe) or to the reaching of the phase of real subsumption and thehegemonising tendency of labour to become immaterial (Hardt and Negri), or

+ , # +# B ? #

# - # *+ % #

4 # + 0

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

9/14

whether the presence of the outside is still with us as a necessary componentof accumulation (Luxemburg and Harvey), in all these cases the definition ofthe outside in terms of its presence or absence is a function of something thatis created ex-ante and that, in this fashion, can come to an end through thedevelopment of capitalist processes (Wolpe, Hardt and Negri) or is in the

processof coming to an end by ongoing dispossessions (Luxemburg, Hervey).

More in general, within the traditional Marxist discourse and moving beyondthe authors reviewed, we face a key problem in the conceptualisation of theoutside. It seems to me that this presents itself either as historical pre-capitalist ex-ante, or a mythological revolutionary post-capitalist ex-post. Inthe middle, there is the claustrophobic embrace of the capitalist mode ofproduction, withtin which, there seems to be no outside. In these terms, it isclear how the historical process of moving from one to the other has tended to

be conceived in terms the deus ex-machina of the party bringingconsciousness to the masses . . .from where? Precisely, from a fetishised

outside.

What is implicitly left out here is that processes of struggles are continuouslygenerating the outside. Our outside, or, maybe plural, our outsides, seem tohave been left out of the picture, left unproblematised in at least threedimensions:

a) in their constituent communitarian features of production of commonsand value practices (degrees of reproduction/challenges/overcoming ofgender, racial or other hierarchies, in a word the shape and form of theproduction of commons in different contexts);

b) in the forms, degrees, and processes of articulation of these constituent

featuresemerging in context specific places11to broader capitals loopsand global markets disciplinary processes;

c) in the nature and effectiveness of the challenge that these constituentprocesses pose to broader capitals loops and global markets disciplinaryprocesses.

In a word, what is left out is very obvious to the eyes of many participating instruggles and providing sympathetic ethnographical accounts: only people in

struggle, deploying specific discourses empowering them in their specificity,are co-producers of alternatives.12And if this is the case, much work is needed to

11 - + * + #

# - 5

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

10/14

relate the multitude of existing or possible ethnographies of struggles, to thegreat scheme of things. Namely, the problematic of contrasting a socialforce which conatus of self-preservation depends on a boundless drive todispossess, measure, classify, discipline the global social body and pitsingularities against each other by withdrawing means of existence unless oneparticipate in the race resulting in the threat of somebody else livelihood (theycall this, the market).

The problematic we have in front of us is thus how do we articulate andproduce commons among so diverse and place-specific struggles so as toconstitute a social force that threatens the self preservation of capital and atthe same timeposit its own self-preservation predicated on different type ofconatus and different type of value practices.But this is a big, too big of aquestion, for which I do not have an answer. Only a suggestion for a place tolook: the detritusas a condition for the production of commons and thetension detritus-conatusas its driving energy.

III

In the first section I have argued that the outside is the process of becomingother then capital. This process of becoming other then capital is more trivialthan we might think. Although it often appears as heroic outburst in whichthe new emerges through the phase time dimension of struggles accountedfor by many ethnographies, its underlying character is rooted in the dailypreoccupations that find expression in circular time and routines which arenecessary to reproduce life, to give form to a singularitys conatus of self

preservation. And this in a world that put us all in condition to articulate ourconatus of self preservation to that of capital. Let me exemplify.

# + & > + & + + &

A> + - # -# 0 +

3> 8 +

+ , + ) , #

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

11/14

A woman picks up the rubbish in a tube carriage in post-modern London.She might be from Eastern Europe or Western Africa, only the colour of herskin might tell. In one of the most expensive town on earth, she is paid 5.05an hour, regardless whether it is night or day, holy day or not; she has even topay for the transport in a tube carriage to travel to the station in which shewill clean carriages. Her daily return fare will cost her about one hour of herdaily work. On Friday and Saturday nights she will have to clean the orangevomit produced by stressed out immaterial workers, drowning theirfrustrations for not having met targets set at the office, or celebrating apromotion (a step in the wage-ladder that differentiate the social body in theeye of capital), or simply attempting to recover a sense of the self by looseningup from the codes and measures that define their character in formal businesscontexts.

What is that make the woman take up a crap job, for a crap wage but her

conatus of self-preservationand that of her community, perhaps a child, ayounger sister and a mother somewhere else in the world waiting for her tosend some cash under the threat of dispossession of their land or house? Orperhaps her conatus of self-preservation led her to take up a crap job far awayfrom home because it allowed her to escape from violent conditions in thecommunity she was born and bread, a violent man, a husband, a father, a

brother? And what is her daily struggle to turn up at work and maintainsanity vis--vis the ongoing humiliating measuring processes of her doing,continuously attempting to minimise cost, to minimise waste, hencemaximise the detritus inscribed in the body of this woman and others likeher? And when this woman together with others like her, articulate their lives

in struggles for better working conditions, wages, or a free travel card, what isthis struggle but the turning of detritus? And what is theproduction of thiscommon wealthif not the common emerging from all struggles presenting itselfin the twofold character of re-possession of social wealth if the strugglesucceed as well as the constitution of new relational practices and newcommunities among the struggling subjects?

What I am trying to say here is this: detritusis the common condition of asocial body divided in a hierarchy with respect to the access to social wealthfor the reproduction of livelihoods. Detritus is certainly posited and appearsin diverse form, a multitude of forms, but it is a common condition faced by

subjects and their communities whose conatus of self-preservation must bearticulated, in a variety of degrees, to the conatus of self-preservation ofcapital. And the latter, certainly demand its toll, hence produces detritus inour bodies and in our environments. In this respect, detritus is a common yetstratified ground or condition, with its own manure, out of which desires

flourishand, to put it with Gilles Deleuze, are producing reality. But theyproduce reality in different conditions. Some of these desires are siphoned

back into the circuits of capital through commodity exchanges and connection

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

12/14

to disciplinary and enclosure processes of global loops. Some are siphonedback in these circuit by necessity; some other by free consumer or citizenchoice; some other as a result of successful strategies of marketing agencies;and some other still by a mixture of these. In so far this happens and ithappens at an increasing level, the social force we call capital can self-preserve itself.

However, other desires emerging from the detritusdo not reproduce thereality of the circuits of capital. Social reproduction is a greater set thancapitalism and its circuits, and it is predicated on webs of relationalpractices which far exceed those constituted by capitals measure and theoutside that capital successfully articulate to its conatus (say the reproductionof bodies qua labour-power).

Some of these desires-creating-reality posit a direct relation to nature,whether this is in a productive relation with the land to reproduce ones

communitys livelihoods as much as autonomously from disciplinary marketsas possible; or simply, a different level of the wage hierarchy, a re-creativerelation to nature, in which the reproduction is not uniquely of thecommodity labour power, but of values and perspectives that are other thancapital. Other desires still are constituted out of clashes and conflict within thesocial body. In this cases, detritus is a condition of reproduction of racial,gender, and other hierarchies in which power, understood with Foucault asthe effect on action, pushes the receiving ends in these hierarchies tochallenge (through communication, negotiations and straggle) the meaningsof community of which they are allegedly part of. Alternatively, thedetritus is a condition of escape, exodus. Indeed, some time the conatus of

self-preservation of identities gives rise to dangerous games, especially whenthe identities in question produce effects at the receiving ends of which theymight want to call sexist, racist, homophobic and so on.

Finally, still some others desires emerging from the condition of detrituscreate convivial and horizontal commons, whether this happen in the contextof the daily struggle for the reproduction of necessity and self-preservation,or in heroic and intense outburst of collective activities that constitutestruggle as the limit of capitals conatus and the terrain of new commons. Theoutside, or better, our outsidesare all here, in the diverse processes of theconstitution of commons and in the problematic of their articulation,

preservation, reproduction andpolitical recompositionat greater scales of socialaction. 13

13& ++

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

13/14

References

Bonefeld, Werner (2001) The Permanence of Primitive Accumulation:Commodity Fetishism and Social Constitution, The Commoner, N.2,September 2001, http://www.commoner.org.uk/02bonefeld.pdf.

Caffentzis, George. 2002. On the Notion of a Crisis of Social Reproduction: atheoretical Review. In The Commoner, N. 5.http://www.commoner.org.uk/caffentzis05.pdf.

Caffentzis, George. 2005. Immeasurable Value? An Essay on Marxs Legacy.In The Commoner, N. 10.

http://www.commoner.org.uk/10caffentzis.pdf.

Cleaver, Harry. 2005. Work, Value and Domination On the ContinuingRelevance of the Marxian Labor Theory of Value in the Crisis of theKeynesian Planner State. In The Commoner, N. 10.http://www.commoner.org.uk/10cleaver.pdf.

Chari, Sharad. 2005. Political Work: the Holy Spirit and the Labours ofActivism in the Shadow of Durbans Refineries. In From Local Processes toGlobal Forces. Centre for Civil Society Research Reports. Volume 1. Durban:University of Kwazulu-Natal, pp.87-122.

Damasio, Damasio, Antonio. 2003. Looking for Spinoza. Joy, Sorrow and theFeeling Brain, London: William Heinemann.

De Angelis, M. (2004) Separating the Doing and the Deed: Capital and theContinuous Character of Enclosures.Historical Materialism,12.

De Angelis, Massimo. 2005. The Political Economy of Neoliberal GlobalGovernance. Review,XXVIII.

De Angelis, Massimo. Forthcoming. The Beginning of History: Value strugglesand global capital. London: Pluto Press.

0 0 0

0

-

8/12/2019 De Angelis Enclosures and the Outside

14/14

Desai, Ashwin. 2002. We are the poors: community struggles in post-apartheidSouth Africa, New York, Monthly Review Press.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri. 2000. Empire, Cambridge, Mass: HarvardUniversity Press.

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri A. 2004.Multitude. War and Democracy inthe Age of Empire, New York, The Penguin Press.

Hart, Gillian. 2002. Disabling Globalization. Places of Power in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Pietermartzburg: University of Natal Press.

Hart, Gillian. 2005. Denaturalising dispossession: Critical Ethnography in theAge of Resurgent Imperialism. In From Local Processes to Global Forces. Centrefor Civil Society Research Reports. Volume 1. Durban: University ofKwazulu-Natal, pp. 1-25.

Harvey, David. 2003. The New Imperialism, New York, Oxford UniversityPress.

Luxemburg, Rosa. 1968. The Accumulation of Capital. New York: MonthlyReview Press.

Marx, Karl. 1858. Grundrisse, New York: Penguin 1974.

Marx, Karl. 1867. Capital. Volume 1. New York: Penguin 1976.

Negri, Antonio (1994) Oltre la legge di valore, DeriveApprodi5-6, Winter.

Perelman, Michael (2000) The Invention of Capitalism. Classical Political Economyand the Secret History of Primitive Accumulation, Durham & London: DukeUniversity Press.

Wolfowitz, Paul. 2005. Charting a Way Ahead: The Results Agenda. 2005 Annual

Meetings Address. The World Bank GroupIWashington, D.C., September 24.Available at http://web.worldbank.org/. Last accessed 25 Feb 2006.

Wolpe, Harold. 1972. Capitalism and Cheap Labour-Power in South Africa:from Segregation to Apartheid. In Economy and Society1: 425-456.

World Bank. 2005. South Africa: An Assessment of the Investment Climate. NewYork.