Danish Stable Schools for Experiential Common Learning in Groups ...

Transcript of Danish Stable Schools for Experiential Common Learning in Groups ...

u n i ve r s i t y o f co pe n h ag e n

Danish stable schools for experiential common learning in groups of organic dairyfarmersWaarst, M.; Nissen, T.B; Østergaard, I.; Klaas, Ilka Christine; Bennedsgaard, T.W.;Christensen, J.Published in:Journal of Dairy Science

DOI:10.3168/jds.2006-607

Publication date:2007

Document VersionPublisher's PDF, also known as Version of record

Citation for published version (APA):Waarst, M., Nissen, T. B., Østergaard, I., Klaas, I. C., Bennedsgaard, T. W., & Christensen, J. (2007). Danishstable schools for experiential common learning in groups of organic dairy farmers. Journal of Dairy Science,90(5), 2543-2554. DOI: 10.3168/jds.2006-607

Download date: 07. Apr. 2018

J. Dairy Sci. 90:2543–2554doi:10.3168/jds.2006-607© American Dairy Science Association, 2007.

Danish Stable Schools for Experiential Common Learningin Groups of Organic Dairy Farmers

M. Vaarst,*1,2 T. B. Nissen,† S. Østergaard,* I. C. Klaas,‡ T. W. Bennedsgaard,*2 and J. Christensen§*Danish Institute of Agricultural Sciences, P.O. Box 50, DK-8830 Tjele, Denmark†Organic Denmark (The Danish Organisation of Organic Farmers), Frederiksgade 72, DK-8000 Arhus, Denmark‡Department of Large Animal Sciences, Section for Production and Health, The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University,Groennegaardsvej 2, DK-1870 Frederiksberg, Denmark§Organic Dairy Company ‘Thise’, I/S Ve & Vel, Byrsted, DK-Nibe, Denmark

ABSTRACT

The farmer field school (FFS) is a concept for farmers’learning, knowledge exchange, and empowerment thathas been developed and used in developing countries.In Denmark, a research project focusing on explicit non-antibiotic strategies involves farmers who have activelyexpressed an interest in phasing out antibiotics fromtheir herds through promotion of animal health. Oneway of reaching this goal was to form participatoryfocused farmer groups in an FFS approach, which wasadapted to Danish conditions and named “stableschools.” Four stable schools were established and wentthrough a 1-yr cycle with 2 visits at each of the 5 or 6farms connected to each group. A facilitator was con-nected to each group whose role was to write the meet-ing agenda together with the host farmer, direct themeeting, and write the minutes to send to the groupmembers after the meeting. Through group focus inter-views and individual semistructured qualitative inter-views of all participants, the approach of the farmers’goal-directed work toward a common goal was judgedto be very valuable and fruitful and based on a commonlearning process. Complex farming situations were thefocus of all groups and in this context, problems wereidentified and solutions proposed based on each farm-er’s individual goals. In this article, we describe theexperiences of 4 stable school groups (each comprisingfarmers and a facilitator), and the common process ofbuilding a concept that is suitable for Danish organicdairy farming.Key words: organic dairy farming, animal health plan-ning, farmer empowerment, common experientiallearning

Received September 18, 2006.Accepted November 28, 2006.1Corresponding author: [email protected] address: University of Aarhus, Faculty of Agricultural

Sciences, P.O. Box 50, DK-8830 Tjele, Denmark.

2543

INTRODUCTION

Organic livestock farming emphasizes health promo-tion and disease prevention with the goal of minimizingthe need for disease treatment, allowing as much natu-ral behavior and natural living for the animals as possi-ble (DARCOF, 2000; Hovi et al., 2004; Verhoog et al.,2004). In European organic livestock farming, antibi-otic treatment is allowed but with some restrictions,such as a prolonged withdrawal time for milk and meat.In Denmark, a discussion among organic milk produc-ers was initiated in 2001 around the goal of phasingout antibiotics from organic dairy herds. In 2004, acombined research and development project was initi-ated to develop strategies and follow the health condi-tion and management of the herds with the explicit aimof phasing out antibiotics (Vaarst, 2006).

The only sustainable way of reducing or eliminatingthe use of antibiotics and other medical treatments ina given herd is to eliminate the need for treatmentsthrough far-reaching health promotion and disease pre-vention initiatives. Clearly, these initiatives must bebased on the conditions on each farm, the goals andpriorities of the farmers, and the nature of the problemson the individual farm. Identifying the possibilities andinitiating individual strategies on widely differingfarms to phase out antibiotics seemed a large and com-plex task. One way of starting this process is to formsmaller groups of farmers who can work together, ex-change experience, guide each other, and form a com-mon learning environment.

Different approaches exist to farmer groups world-wide. In Denmark, so-called erfa-groups (erfa is an ab-breviation of erfaring, the Danish word for experience)have been widely used for decades for disseminationof new knowledge and ideas to and among farmers,focusing on themes for each meeting such as parasitecontrol, winter feeding strategies, or the use of bodycondition scores. In East Asia and Africa, so-calledfarmer field schools (FFS) have been developed (Anony-mous, 2003). These are groups for common learning

VAARST ET AL.2544

and development of farming systems for their local con-ditions, including economic conditions. The FFS arewidely used to alleviate poverty and to empower poorfarmers through education and common learning.Drawing upon practical experiences with this approachin Uganda (Vaarst et al., accepted) and knowledge ofDanish erfa-groups, an approach of forming farmergroups was chosen to be the main method to reach thecommon goal of phasing out antibiotics. These groupswere named “stable schools” and were adapted to theidentified needs and preconditions to support the farm-ers in fulfilling their specific goals.

We describe the practical framework of a 1-yr courseand the farmers’ evaluation of it, and discuss the rele-vance of the stable school approach to the overall goalof phasing out antibiotics from organic dairy herds, aswell as other approaches to advisory (veterinary) ser-vice in relation to the development of the individualfarmer and of organic dairy production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Setting: The Change in the DanishFarming Environment

Danish dairy farming has been undergoing a dra-matic development during the past few decades. In1985, 1995, and 2005, the number of farms with dairycows was, respectively, 31,800, 16,000, and 6,500, withan average herd size of 28, 44, and 86 cows (StatBankDenmark, 2006). Over the same period, the proportionof herds with more than 100 cows has increased from1% in 1985 to 4% in 1995 and to 38% in 2005 (StatBankDenmark, 2006). In 2003 and 2004, 430 new dairy cattlehousing systems were built (Rasmussen, 2005). In 2004,74% of Danish dairy cows were housed in loose housingsystems with an average herd size of 110 cows (Skjøthet al., 2005). High demands are put on the farmers’skills not only to manage the animals and crops, butalso to find their way in a jungle of subsidies, regula-tions, record keeping, and forms to complete. Mostfarmers who are still in business can be assumed to bevery skilled farmers who are in a favorable economicsituation, have a clear attitude about the future forthemselves and their farms, and are very busy manag-ing their farms. Through agreements with dairy andother companies, their market situation is usuallyclear, with a 5-yr guarantee for delivering milk for acertain price. After this time, new negotiations aboutprices and terms take place.

Project Framework

The project was initiated as an action research projectinvolving the Danish organization of organic farmers

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

(Organic Denmark), a private dairy company (Thise;at the start of the project owned by 46 organic milkproducers), and the Danish Institute of AgriculturalSciences. The aim was to phase out the use of antimicro-bial drugs (antibiotics) from organic dairy herds. It wascrucial for the project that drugs should be phased outby eliminating the need for disease treatment throughminimizing the disease level in the herds. Because theuse of antimicrobial drugs varies widely in differentherds and is complex, many different approaches canbe taken. It was therefore decided that the main ap-proach was to design individual farm and herd strate-gies through a participatory process using farmergroups for mutual advice and common learning.

Selection of Herds, Farmer Groups, and Facilitators

The 46 organic milk producers connected to the Thisedairy company were potential participants. At a meet-ing for the dairy producers, all producers were askedwhether they would be interested in participating.Twenty-two volunteered from the start, and 1 addi-tional farmer was allowed to join the project 4 mo afterinitiation. During the project, 2 herds went out of milkproduction. Table 1 presents data on herd size, level ofproduction, SCC, and mastitis treatments. The re-maining 23 farmers who did not volunteer to participatewere not systematically asked why they declined. How-ever, 6 or 7 of them contacted the project group to saythey found initiative interesting but had no time orhad participated in previous project activities on othertopics (e.g., paratuberculosis) and felt that they couldnot spare the time that participation would require.

The farmers agreed to give a high priority to keepingdriving distances down when forming groups, and whenall volunteers had signed up for participation in theproject, the chair of the dairy company formed 4 groupsbased solely on location. In 1 group, 3 of the farms wereplaced far away from all the others. The longest drivingtime within this group was approximately 1.5 h be-tween 2 farms. In other groups, the driving time wasbetween 15 and 45 min. It was suggested in the finalinterviews that the driving time between farms partici-pating in a group should not exceed 45 min.

The facilitator was originally a cattle production advi-sor in Organic Denmark, and was the project partnerin this project. He had undergone a 1-yr program inteaching, learning, and communication before this proj-ect, but had no previous practical experience in groupfacilitation.

Data Collection

The following data were collected. First, individualinterviews were conducted with each farmer at the be-

OUR INDUSTRY TODAY 2545

Tab

le1.

Pre

sen

tati

onof

the

23di

ffer

ent

part

icip

atin

gh

erds

inth

e4

stab

lesc

hoo

lgr

oups

(1th

rou

gh4)

Mas

titi

str

eatm

ent

No.

ofC

alcu

late

dpe

r10

0co

ws

inM

ilk

yiel

d,S

CC

,co

w-y

ears

,H

erd

Bre

ed1

2004

2004

(200

3)2

2004

(200

3)3

Hou

sin

gsy

stem

,20

0420

04(2

003)

4O

ther

char

acte

rist

ics

Gro

up

1(M

arch

2004

–Feb

ruar

y20

05)

A5

DH

827,

100

(6,4

00)

393

(339

)D

eep

litt

er12

(13)

Au

tom

atic

(rob

otic

)m

ilki

ng

syst

emB

Jers

ey72

6,90

0(7

,100

)29

4(2

73)

Dee

pli

tter

1(1

7)C

DH

438,

100

(8,2

00)

132

(113

)T

ied

23(5

2)D

5D

H13

57,

600

(7,9

00)

335

(356

)S

latt

edfl

oor/

stra

w14

(44)

Hei

fer

hot

el6

ED

H80

7,40

0(7

,300

)45

6(3

08)

Sla

tted

floo

r/st

raw

31(2

3)F

DH

659,

000

(8,2

00)

173

(217

)S

latt

edfl

oor/

mat

s+

saw

dust

12(2

5)A

uto

mat

ic(r

obot

ic)

mil

kin

gsy

stem

Gro

up

2(M

arch

2004

–Mar

ch20

05)

GD

H49

7,50

0(6

,700

)36

8(4

13)

Tie

d/de

epli

tter

34(4

6)H

Jers

ey11

67,

800

(7,9

00)

304

(275

)S

latt

edfl

oor/

saw

dust

10(1

9)I

Jers

ey51

6,60

0(6

,300

)23

2(1

89)

Dee

pli

tter

14(6

)J

Jers

ey35

6,90

0(6

,200

)22

7(2

15)

Dee

pli

tter

8(0

)O

utd

oor

acce

ss;

seas

onal

calv

ings

KD

H61

8,90

0(8

,600

)21

9(2

15)

Sla

tted

floo

r/st

raw

51(6

7)G

rou

p3

(Mar

ch20

04–A

pril

2005

)L

Cro

ss15

37,

000

(6,9

00)

325

(209

)D

eep

litt

er4

(10)

Ou

tdoo

rfe

edin

gta

ble

wit

hT

MR

7

MD

H11

16,

900

(6,7

00)

303

(339

)D

eep

litt

er2

(8)

Ou

tdoo

rfe

edin

gta

ble

wit

hT

MR

NJe

rsey

456,

300

(5,7

00)

135

(177

)D

eep

litt

er0

(3)

Ou

tdoo

rac

cess

;su

ckle

rau

nts

;se

ason

alca

lvin

gsO

DH

386,

100

(6,3

00)

264

(414

)D

eep

litt

er(b

uil

tn

ew)8

8(4

6)H

eife

rh

otel

PD

H70

7,90

0(7

,800

)15

5(1

82)

Sla

tted

floo

r(b

uil

tn

ew)8

3(4

)O

utd

oor

acce

ss;

suck

ler

aun

ts;

seas

onal

calv

ings

W5

DH

587,

000

(6,8

00)

248

(263

)D

eep

litt

er11

(12)

Su

ckle

rau

nts

Gro

up

4(M

arch

2004

–Mar

ch20

05)

QJe

rsey

345,

600

(5,8

00)

301

(289

)L

oose

hou

sin

g0

(0)

RD

H84

7,50

0(6

,300

)23

7(2

69)

Sla

tted

floo

r/m

ats

+st

raw

3(1

3)S

Jers

ey78

6,00

0(5

,600

)30

2(3

32)

Sla

tted

floo

r/st

raw

0(0

)T

DH

937,

700

(6,6

00)

263

(266

)D

eep

litt

er9

(23)

Hei

fer

hot

elU

Jers

ey15

06,

800

(6,5

00)

298

(260

)D

eep

litt

er15

(14)

Her

dsi

ze+5

0%du

rin

gpr

ojec

tye

arV

Jers

ey43

6,80

0(6

,300

)26

3(1

73)

Dee

pli

tter

7(2

)

1 DH

=D

anis

hH

olst

ein

-Fri

esia

n;

Cro

ss=

diff

eren

tbr

eeds

,in

clu

din

gD

Han

dJe

rsey

.2 C

alcu

late

d30

5-d

prod

uct

ion

aski

logr

ams

ofE

CM

for

cow

sca

lvin

gin

Au

gust

2002

–Ju

ly20

03(2

003)

and

inJa

nu

ary

2004

–Dec

embe

r20

04(2

004)

.Cal

cula

ted

asde

scri

bed

inB

enn

edsg

aaar

det

al.

(200

3).

3 Cal

cula

ted

from

mon

thly

indi

vidu

alco

wS

CC

,×1

,000

cell

s/m

L.

4 Vet

erin

ary

trea

tmen

tsw

ith

anti

biot

ics.

5 Far

mer

sA

and

Dso

ldth

eir

mil

kqu

ota

duri

ng

the

proj

ect

peri

od.

Far

mer

Apa

rtic

ipat

edin

4an

dfa

rmer

Din

9st

able

sch

ool

mee

tin

gs;

farm

erW

ente

red

the

proj

ect

atth

efi

fth

mee

tin

gin

the

grou

p.6 C

alve

sso

ld/b

rou

ght

up

ona

coll

abor

atin

gfa

rmat

1to

4w

kof

age

and

bou

ght/

incl

ude

din

the

her

dbe

fore

calv

ing.

7 TM

Rin

clu

ded

rou

ghag

ean

dco

nce

ntr

ate;

inso

me

case

s,th

isis

com

bin

edw

ith

feed

ing

ofco

nce

ntr

ate

inth

em

ilki

ng

parl

or.

8 Bu

ilt

new

hou

sin

gsy

stem

duri

ng

the

proj

ect;

farm

Pbu

ilt

ade

epli

tter

syst

eman

dcl

osed

the

stab

lew

ith

slat

ted

floo

r.

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

VAARST ET AL.2546

ginning and the end of the project (the method is de-scribed below). Second, group interviews of the 4 stableschools were conducted at the last meeting of eachgroup to evaluate the project and the concept of stableschools. This interview focused on the whole frameworkof the groups, the meetings, the role of the facilitator,and factors such as the differences among herds andhow this had influenced group work and common learn-ing. Finally, the first author of this article participatedin one-third of the monthly stable school meetings andhad regular discussions and follow-ups with the facilita-tor of the 4 groups.

The Qualitative Semistructured Interview Approach

The individual qualitative research interview is aresearch method that aims to explore and describe aspectrum of attitudes and experience within a certainfield, rather than presenting a representative sampleof opinions or quantifying opinions or experience amonga group of people (Strauss and Corbin, 1990; Kvale,1996). All participating farmers were individually in-terviewed by means of this method at the beginning andthe end of the project. All interviews were performed bythe first author and recorded on tape. Each interviewlasted 60 to 100 min, preceded by a 30-min walking tourof the farm. The interviews were structured accordingto several thematic questions. In the last interview(which is focus of this article), the focus was primarilyon changes at the farm during the project, includingthe decisions, process, and perceptions related to thesechanges. The individual farmer’s experience with hisor her participation in the stable schools was treatedin depth during the interviews. The interviewee wasencouraged to speak and direct the course of the inter-view, and the interviewer followed up on his or herquestions, explored apparently self-contradictory state-ments, asked for examples, and tried to keep to the pointand the theme of the interview. A written summary wasmade and sent to the farmer for confirmation. Quota-tions of what the farmer said were included in thissummary. This approach was chosen to confirm thatthe interviewer had correctly understood the importantmessages and conclusions of the farmer regarding hisor her experience with the stable schools. A full tran-scription was difficult to read (because it containedpauses and interruptions) and did not contain any inter-pretation, unlike the summary, in which some state-ments were summarized and background for conclud-ing remarks was given, which were also included in thedocument confirmed by farmers. Overall themes weredescribed across the interviews in an approach modifiedfrom Strauss and Corbin (1990).

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

RESULTS

The Practical Framework of the Meetings

One year’s worth of work in the group was requiredby the project structure. The farmers decided to meetmonthly in groups of 5 or 6, based on an estimate ofthe time they felt that they could spend on meetings.During the 1-yr period they met twice at each farm,with approximately 6 mo between the 2 meetings onthe same farm, so that at the second meeting they couldsee changes and improvements initiated by the hostfarmer as a result of the first meeting. The farmersagreed on meetings lasting 2.5 to 3 h. During the firstmeetings, a routine was developed of spending approxi-mately 1 h in the stable and field, and 1.5 to 2 h indoorswith discussions around the table, as illustrated in Fig-ure 1. In Figure 2, the practical arrangements of meet-ings are summarized. This practical framework, as wellas the structure of the meetings including the agenda,data from the farm, and the role of the facilitator, wasjudged appropriate under Danish organic farming con-ditions, where farmers are usually under time pressurebut are generally skilled in looking at data from herdsas well as buildings, feed, and animals. Making anagenda gave the farmers in the group an opportunityto be prepared for the next meeting, and stimulatedthe host farmer for each meeting to think through whatactually were the successes and problem areas in theherd on which they would focus.

The Common Goal for Widely Differing Farms

As illustrated in Table 1, the participating farms dif-fered widely regarding the structure of the farmingsystem, the herd size, breed, daily management rou-tines, and goals of the farmer. The group focus inter-views revealed a general agreement in all 4 stableschools that the common goal challenged all farmersand made it interesting to work with farms differentfrom one’s own. The fact that a goal carried the processshould be clearly distinguished from having a themeas the foundation of the group, as expressed by farmerW in the group focus interview:

“I want to emphasize the importance of the factthat this is not a theme, this is a GOAL. That isdifferent. I mean, we have a common goal to phaseout antibiotics. … Not like just discussing ‘feedingstrategies,’ right? … It is not just discussing how tofeed one’s cows, but ‘how do we work towards thisgoal?’ with all the facets this may have.”

A goal can be reached in as many ways as there areparticipating farms, and demands an analysis of theconditions for each herd, farmer, and farm.

OUR INDUSTRY TODAY 2547

Figure 1. In the stable schools in Denmark, the farmers start with a farm walk, where the group gets an impression of the farm. Afterthis, the farmers sit down and examine the results of the farm in terms of, for example, production, health and disease patterns, feedingplans, and calving patterns and findings in clinical examinations of the animals in the herd.

The Farm’s Individual Goals and Focus Areas:Ensuring the Relevance of the Advice Givenin Each Group

In the initial phase of each farm meeting, the farmerexplained the goals and values of his or her individualfarm. It could mean, for example, that they wantedtime and resources for a good family life, or that theywanted as much outdoor life for the animals or as exten-sive a way of farming as was possible under Danishconditions. It could also mean that they did not wantto increase the farm size to make things work, or thatthey wanted to work toward more self-sustainability interms of feeding and biosecurity on the farm. In theevaluation, this was emphasized as crucial for directingthe advice of the fellow farmers to the farmer on thefarm, to make it relevant to this particular farm andherd, as articulated by farmer P:

“As far as I remember we all started telling aboutone’s goals, and then it is a duty for us, who come asvisitors to that particular farm, to try and under-stand those goals. It does not work if you just wearyour own glasses and say ‘This way of farming—it

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

is best that you just close the farm right away,’ butrather to step into this and say that ‘if you havethese goals then I can see the following possibilityfor fulfilling them.’”

The immediate goals could be characterized as identi-fied focus areas, which were also visible in the agendafor the meeting on the host farm. They also were ofdifferent types, and in most cases were directly linkedto animal health promotion issues, such as “improvedsomatic cell counts in the herd,” “less lameness,” or“build good outdoor facilities.” In some cases, these wererather broad, as with farmer W, who focused on workingroutines during the day and during the week to decreasestress, hoping in this way to make better observationsof the herd and take better care of individual animals.

One of the participating farmers gave a presentationat the 2006 Danish Organic Congress about her experi-ences with stable schools. She emphasized the impor-tance of including the individual goals and lives of eachparticipant in combination with the common goals forthe stable schools (Olsen, 2006; translated by thefirst author):

VAARST ET AL.2548

Figure 2. The practical framework of the meetings in the stable schools, as developed in the project and evaluated to fit the conditionsfor Danish farmers.

“Our stable school had life as a farmer as a startingpoint, being organic as a precondition, and phasingout of antibiotics as a goal. The stable schools haveclarified in my mind what the problems were on myfarm. The mutual trust among the participants madeit possible for us to go far with each other and totouch the problem areas that hurt.”

Whether the goals and focus areas had been fulfilled,and with what outcomes, were difficult to evaluate inan unambiguous way after 1 yr. All farmers, withoutexception, had committed themselves to finding solu-tions to identified problem areas, and by the secondmeeting on all farms, new initiatives and improvementshad been started. In some herds, the improvementsalready had measurable effects, such as fewer cases ofcalf diarrhea or lameness compared with earlier evalua-tions in the herd.

Learning from the Successful Case of Each Farm

At each meeting, the host farmer was supposed totell about one area or case of success in the host herd.It could be a type of equipment, such as the water supplyfor the herd or a new outdoor pathway with a gooddrainage system, or it could be a management routinethat improved the health situation, such as separatingthe dry cows completely from the lactating herd or at-tracting the cows to the feed right after milking to avoidtheir lying down in the litter with their udder and theirteat canals still open. This created room for the hostfarmer to tell about something that had been solvedand turned out to be a success in this herd, and notonly to focus on the 2 selected problem areas (see Figure2). The successful cases were very interesting for the

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

other farmers, because many of them involved innova-tive, context-related thinking and practice-based trial-and-error stories from which all could learn.

The Feeling of Being Equally Interesting as GroupMembers from Different Farms

During the evaluation in individual interviews aswell as in group interviews, all participants describedthe positive side of having been members of groups withmutual trust, respect, and openness, and the feelingof having equal rights to tell about experiences, giveopinions, and be able to contribute. In some cases, thiswas contrasted to other experiences the farmers hadhad, as farmer J explained:

“Here, I compare this group with another erfa-group I once attended. In the other group—maybemore than in this group—I was the one owning thesmallest herd, although the difference was not allthat big. But there in the other group, I had thisfeeling that some of the other farmers thought myfarm was a ‘nothing’ that could not really contributeto anything. It was too small, and when they werehere, it felt as if they immediately stopped lookingaround and started talking about something com-pletely different. That has not happened in thisgroup—at no point have I had the feeling that whathappened here was not fully professional, competent,or interesting, or was something you could not learnfrom or use for anything.”

Farmers in all groups agreed that the differencesamong farms in size, breeds, and practices, such asseasonal calving, were an advantage. It was empha-

OUR INDUSTRY TODAY 2549

sized that when it was a matter of reaching a commongoal such as the one in this project, all experienceswere relevant.

The Role of the Facilitator

The role of the facilitator developed into 3 main well-defined tasks: 1) to make an agenda for the next meetingin collaboration with the farmer and send it out to allgroup members together with key figures from the herd;2) to help the group through the discussions and directthe meeting to keep to the schedule; and 3) to write areport, including the decisions made, after the meeting.

In this project, 1 facilitator was involved in all 4groups. His way of managing the role was generallyvery well received by all participants, and it was empha-sized that it was a big advantage that he was a facilita-tor and did not take the role of an “expert.” In one groupfocus interview, a farmer raised the question of whetherthe facilitator should have been more “aggressive” andasked more critical questions, acting more like an ani-mal health professional. In the individual interviewsafterwards, all farmers except this one said that whatthey would want and expect from a facilitator was ex-actly what they had experienced in practice in thesegroups, namely a person who guides the process andthe discussions and allows the farmers be active, criti-cal, and advising colleagues. Based on this, we con-cluded that the development of the facilitator role hadtaken an appropriate direction through the process andhad been shown, in practice, to work well. The learningexperience of being a facilitator was profound with re-spect to shifting from the role of an advisor (who feltresponsible for having an answer to all possible ques-tions and being able to teach farmers about correctmanagement routines, for example) to the role of a facil-itator (who concentrated on guiding and keeping thefocus on a process and a dialogue among group parti-cipants).

Animal Health Professionals Do Not Takea Whole-Farm Approach

In the individual and the group focus interviews, itwas emphasized that the whole farm was in focus, in-stead of a more narrow focus on feeding or milking, forexample. Furthermore, the focus was on health promo-tion and disease prevention rather than disease treat-ment. In one group focus interview, the farmers’ experi-ences with animal health professionals (particularlyveterinarians) were contrasted with the focus area inthis project, as illustrated in the dialogue given in Fig-ure 3.

The groups had a common goal—phasing out antibi-otics from organic herds—but it seemed as if no animal

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

health professional was willing or knowledgeable aboutthis, as stated by farmer S, for example:

“Well, taking the issues of penicillin and phasingout, there are no professionals who tell us what todo, right? Only in our own daily practice can we de-velop how things should be, and there we have onlyour own experiences and attitudes. Maybe the thingsthat one person does cannot work on anybodyelse’s farm.”

Group Support to NontraditionalDisease-Handling Approaches

In all groups, farmers had found support to try thingsthat, according to their own statements, they might nothave tried if other farmers had not convinced them. Inall groups, some practices were spread among all oralmost all farmers in the group, such as a certain typeof ventilator in the milking parlor to minimize the num-ber of flies in the summer; using TMR; building outdoorfeeding tables; and taking samples of the drinking wa-ter to test the quality, and improving the hygiene ifnecessary. In stable school group 4, one of the farmershad not used veterinary medical treatment for approxi-mately 15 yr, primarily through creating a robust herdwith great emphasis on the health of the animals, butalso through untraditional approaches, such as extramilking-out by hand in case of mastitis and making hisown oat soup for calves with diarrhea. This farmer wasgiven a central position in discussions about differentapproaches to disease prevention and treatment at themeetings of this group. In the final evaluation, the otherfarmers in this group pointed to the fact that this farmerhad been a driving force for everyone when exploringpossibilities for alternative disease handling methods,based on the argument that “if he can do it, so can we.”

Mutual Trust and Insight into Other Farms

The whole concept that was developed in this processwas based on farmer groups meeting on private farms,where the outcome of the process, the dialogue, andthe success of the meetings were based on access andopenness of each farmer toward the whole group. Datafrom each farm were sent to the whole group beforethe meeting, and the colleagues’ analysis of the herdsituation and later the advice about improvements wasdependent on the farmer not trying to hide anythingand being able to enter into an honest dialogue, wherehis own shortcuts, and in some cases inappropriate rou-tines, to achieve and maintain good animal health andwelfare were exposed to the other farmers in the group.This open-minded approach clearly demands a highlevel of motivation. The success of this process perceived

VAARST ET AL.2550

Figure 3. A conversation between 3 participating farmers about their collaboration with their local practicing veterinarians. *The farmerrefers to veterinary medical products. In Denmark, veterinarians are allowed to give all types of medicine to the farmers including theorganic farmers. According to the regulation on organic farming, the farmers are not allowed to use all these products. Thus, it is theresponsibility of the farmer to check what he or she receives. Some veterinarians are aware of this and include it in their advice.

by the farmers is clearly linked to the open-minded andtrustful attitude in the groups. The existence of thismutual trust is because farmers participated solely outof their own motivation to make an effort to improvetheir farms and to participate in a group process.

Group Life in the Stable Schools

There were no systematic, recognizable differencesin the perception of the project, the stable schools, orthe value of the participatory group approach amongthe 4 groups, as expressed in both the individual andthe group focus interviews. The ways of communicatingand the mutual respect within the group were promi-nent in all 4 groups. However, each group seemed todevelop characteristics from which it could be distin-guished from the other 3 groups. For example, in onegroup’s meeting, there usually were 2 participants from5 of the 6 participating farms, either a husband andwife (from 3 farms) or 2 men who ran the farm together(from 2 farms). In the 3 other groups, only one maleowner of the farm normally participated. Sometimes,the wife at the host farm participated in these groups.Moreover, in 1 group, 1 of the farmers had not usedantibiotics for 15 yr. There was a tendency for the farm-ers in this group to develop a more radical phasing-outpolicy than in the other groups. In another group, 2farmers were eager to stop using antibiotics in cases ofchronic mastitis, which influenced the group towarda less radical policy. In addition, the groups differedslightly with regard to how easily they broke the speak-ing order when not strictly guided by the facilitator.Generally, the farmers rapidly went into a certain well-

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

disciplined way of communicating around the table, butin the case of issues in which they all had experiencesor opinions (such as drying-off routines), they couldstart a more anarchistic discussion. Finally, all 4 groupswere officially closed after 2 rounds of visits to eachfarm, and all 4 groups chose to continue on their owninitiative, but with 4 to 6 annual meetings instead ofmonthly meetings.

DISCUSSION

The Practical Framework of the Meetings

The conduct of meetings obviously fit well into theDanish context as described above as part of the setting.The FFS are often based on weekly meetings lasting 4to 6 h. In the Danish stable schools, the farmers wouldnot be able, nor would find it relevant, to spend somuch time on these meetings. With many farmers indeveloping countries not professionally educated asfarmers, the FFS approach in some ways seems to re-place an education, whereas the Danish approach isused in a very different context. When using the stableschool approach with the aim of improving daily prac-tice and routines, it is appropriate to have a lot of timebetween the meetings, because the experience of imple-menting and seeing the effects of change needs time.The common learning is improved in this way. Whenimplementing concepts like FFS under completely dif-ferent conditions, we conclude that it is crucial to ana-lyze the conditions and context into which the approachfits and then base the newly developed version of theconcept on this analysis.

OUR INDUSTRY TODAY 2551

The Common Learning Process in Stable SchoolsCompared with FFS Principles of Learning

The common learning process and the equality amongparticipants of a group are characteristics of the origi-nal FFS concept (Anonymous, 2003), and served as themain source of inspiration for the stable schools. Khisa(2003) describes an FFS in general terms as “a platformand ‘school without walls’ for improving decision mak-ing capacity of farming communities and stimulatinglocal innovation for sustainable agriculture,” andquotes one of the leading advocates for FFS, Kevin Gal-lagher, as saying that “the farmer field school is notabout technology, it is about people development.”

In the stable schools, a significant learning processtook place as expressed by the participants in the indi-vidual and group focus interviews, and as reflected inthe technical results from the farms, where greatchanges and improvements regarding animal healthwere demonstrated (Klaas, 2006; Klaas et al., 2006;Vaarst, 2006). The question is what made this learningprocess happen in 4 groups of widely different farmersfrom different herds and farms. The 5 key principles ofthe FFS concept as described by Khisa (2003) are asfollows (the authors’ comments regarding the Danishstable schools are in brackets):

1. What is relevant and meaningful is described bythe learner and must be discovered by the learner.[The members of a stable school decide what tofocus on in their own farms and the group buildsits learning and experience on this.]

2. Learning is a consequence of experience. [Commonexperience was built up in the group in terms ofsharing insights into each other’s farms and follow-ing the development after initiation of new routinesand improvements.]

3. Cooperative approaches are enabling. As people in-vest in collaborative group approaches, they de-velop a better sense of their own worth. [Many FFSinvolve forming a formal farmer organization orassociation involving money, which was not re-garded as relevant in Denmark.]

4. Learning is an evolutionary process and is charac-terized by free and open communication, confronta-tion, acceptance, respect, and the right to makemistakes. [A respectful and open dialogue wasachieved in the groups, partially because of the fa-cilitator.]

5. Each person’s experience of reality is unique. Asthey become more aware of how they learn andsolve problems, they can refine and modify theirown styles of learning and action.

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

Each individual’s personal driving force for learningmust not be underestimated. Boud et al. (1985) empha-size the emotional element in the learning: “In particu-lar we give much greater emphasis to the affective as-pects of learning, the opportunities these provide forenhancing in reflection and the barriers which thesepose to it.” They partly relate the feelings on the per-sonal level to the reflection created by the learnersthemselves rather than to activities planned by others.

Situated Learning on Different Levelsin Danish Stable Schools

The common goal is closely linked to the commonlearning process. When working with a common goalin different farm contexts, all movement toward thiscommon goal is relevant for all participants. This goalcan be met in many different ways, and it should alwaysbe met in a way that fits well into the local goals andreality of each individual herd. There, a consciousnessabout and respect for the local circumstances and farm-ers’ priorities and goals are necessary.

The ideas of situated learning are crucial here, wherethe common learning process is embedded in a social,cultural, and personal context, that is, in the local envi-ronment of each farm (Lave and Wenger, 1991). There-fore, learning in groups is an important process whenseen from a community perspective, where the struc-tures (e.g., the roles of farmers and advisors) are repro-duced hand-in-hand with new ideas, or changed.

Empowerment in the Context of DanishStable Schools

A learning process leading to empowerment of farm-ers on a personal as well as the community and societylevel will have a great impact on the farmers’ attitudesand practices; this was also reflected in the results fromthe herds (Klaas et al., 2006). Yet in the Danish setting,empowerment understood as “enabling people to takecontrol over their own life situations” may need to beunderstood in a different context from where it is nor-mally used. The photograph in Figure 1 demonstratescompetent and skilled farmers around a table at a groupmeeting, interpreting data, and analyzing the farm sit-uation based on their own observations and data.

The aim of the Danish stable school groups was tosupport farmers in improving the health status in theirherd and to enable them to phase out antibiotics. Never-theless, there are several ways to reach this goal, andfarmers improved their skills and insight in the generalmanagement of their own herds. The sociocultural partof the process may be closely linked to empowermentof the farmers in a broader understanding. “Empow-

VAARST ET AL.2552

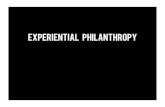

Figure 4. The challenging process of 2 meetings on each participant’s farm over a 1-yr period, where the relationship at each individualmeeting is asymmetric, because one farmer is in focus and the others give input. However, everybody in the group goes through the wholeprocess trying both roles, which creates the common learning environment.

erment” is normally related to the situation of “power-lessness;” for example, often addressing certain under-privileged or marginalized groups in society with regardto race or gender issues, with the aim of empoweringthem to take control over their own lives. In this studythe participants were not generally powerless, and em-powerment in this context is understood rather as acontinuous development on the human and communitylevel, where farmers take responsibility for, and controlof, their own situation as core elements of the commonlearning processes.

The Learning Situation at Each Meetingand in the Group

When looking only at what happens during one meet-ing, it can seem like an asymmetric relationship withinthe group, with one person being advised by a wholegroup. However, all participants in the group in turnare in the same situation and participate under thesame conditions: they and their farms are exposed, ana-lyzed, and given advice, and each participant visits allother farms with the purpose of contributing their ownadvice and experience.

In Figure 4, the learning process is illustrated as achallenging contrast between the individual meetings,where one farmer is in focus during a whole session,with 2 meetings at each farm. The farmers are learningtogether from the process and from the improvementson all farms.

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

Stable Schools Contrasted to Animal HealthProfessionals and Advisory Services

During the final interviews, the stable schools werecontrasted to the ordinary advisory service, and in par-ticular the veterinary service. Veterinarians are nor-mally very involved in a dairy farm, because only veteri-narians are allowed to treat with antibiotics on an or-ganic farm. In these groups, a common learning processhappened that included equality among group mem-bers. This is in contrast to the relationship betweenfarmers and animal health professionals (in this casethe veterinarian), which can be described as an asym-metric power relationship in terms of a meeting be-tween an educated animal health professional and afarmer. In contrast to the situation illustrated in Figure4, the asymmetry is permanent, and the farmer is sup-posed to be the one learning from the professional. Theexpected outcome of an advisory service dialogue is im-provements at the farm based on inputs from the ani-mal health professional, who can (but need not) remainunchanged. In contrast, the farmer is expected tochange his or her attitude, knowledge base, andpractice.

Many similarities can be found between this relation-ship and the relationship between a medical doctor anda human patient. The work of Bourdieu (1990) focusingon symbolic violence can help to understand this asym-metric power relationship. According to Bourdieu, theprofessional will dominate the nonprofessional through

OUR INDUSTRY TODAY 2553

the authority of his own profession and the commonexpectations regarding his knowledge and skills as aprofessional, which are superior to those of the nonpro-fessional (in this case the farmer). Symbolic violencemay affect both the daily communication as well as theoverall collaboration between veterinarians and farmercommunities, which was obvious from the conversationin Figure 3. These farmers seem to reject the veterinar-ian and the knowledge that could be obtained from himor her for several reasons, according to their perception:

1) The veterinarian does not respect the goals of thefarmer, one of which is being organic.

2) The veterinarian focuses more specifically on ani-mal diseases, rather than on the whole farm and,for example, the farmer’s general working situationand priorities, which may influence the animalhealth situation.

3) The asymmetric power relationship seems to berecognized and identified, partly through experi-encing the dialogue and the feeling of equality inthese stable schools.

There are 2 different types of veterinary services ona farm, namely the herd health approach and the indi-vidual animal approach. A veterinarian who is inter-ested in herd health and organic farming is a relevantpotential partner for the farmer. But farmers in thestable schools did not think of their veterinarians asrelevant partners in herd health improvements. Theyfelt that their veterinarians did not support them inbeing organic farmers and in developing daily practicesthat were more in accordance with organic livestockproduction. In this light, the veterinarian did not seemto possess the type of knowledge that they needed,namely knowledge encompassing the whole farm andinvolving more aspects of animal health and welfare.

This does not imply that the veterinarians in thesecases do not possess high-level professional knowledgewhen dealing with diseases and disease treatments ofthe individual animal or the whole herd. According toBourdieu (1990), knowledge is almost exclusively rheto-ric and capital and, as such, is primarily used to main-tain an asymmetric power relationship. Thinking of theveterinarian’s knowledge only in this way, one mayignore the fact that the veterinarians potentially dopossess knowledge that the farmers lack and can benefitfrom. The farmers may acknowledge this when theyhave a diseased animal, but because they do not wantto find themselves nor their animals in situations wherethis particular knowledge is needed, they do not valuethe knowledge of the veterinarian. At the same time,they want an animal health professional who canguide them toward a better herd situation. Therefore,

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

even though the veterinarian can help to develop knowl-edge about diseases and disease control, it seems thatthis was not the type of knowledge that the farmerswanted to focus on in these groups.

The increased focus on improving animal health inthe stable school groups through changed farm prac-tices may lead to an increased wish to involve animalhealth professionals in general farm improvements,taking as the starting point their own goals and a goalsuch as the one in this project of phasing out antibiotics.If the veterinarians do not respond to this request toinvolve the whole farm in their analyses and advice bykeeping the local farm goals in mind or by being rele-vant partners in a sparring or learning process, thestable school process may lead to structural changes inthe relations between the veterinarians and farmers.

Such a development is highly dependent on bothsides’ attitudes, and whether they can handle a changein focus and mode of dialogue. The empowerment ofthe farmer may lead to the conclusion that the farmercan do the animal health planning without the veteri-narian, who does not seem to respond in the right wayto the goals and wishes of the farmer. But it can alsotake another direction, namely to empower the farmerto articulate his or her expectations to the veterinarianin a more concise and precise way in future communica-tions, which could empower the veterinarian by givinghim or her the opportunity to respond to these expecta-tions and live up to the needs expressed by the farmer.

CONCLUSIONS

The farmers participating in this project expressedthe view that the stable school process had been valu-able and had led to concrete improvements in theirherds.

The common goal of a stable school is of crucial impor-tance. The farms, herds, and farmers in the same stableschool can very well be different from each other, aslong as the farmers work toward the common goal andcombine the common goal with the local goal of eachfarm. The farmers own the common experience-basedlearning process, and the participation and the processin the stable schools must be completely driven by thefarmers’ own motivation. Prerequisites for a profound,well-prepared, and meaningful dialogue in a stableschool group are the willingness among all members tolet others gain insight into their farm, an agenda di-rected by the host farmer, and equality among groupmembers in the sense that all experiences and opinionsare perceived as equally valid. The facilitator has a roleof guiding the process and the meetings, and in doingthe practical work. The fact that the facilitator was not

VAARST ET AL.2554

given a role as the expert was crucial for the successof the process.

The interplay between the apparently asymmetricrelationship at individual meetings (one farmer andfarm being in focus for analysis and advice from thewhole group) and the whole process, where all farmerstake both roles, will create a challenging learning situa-tion in the whole group.

The future concept of stable schools in a Danish con-text will be a 1-yr process for farmer groups workingwith learning, advising, and knowledge exchange. Afterthis year, which includes 2 meetings at each farm, itis up to the group whether to continue, maybe in an-other way, such as taking other approaches to the learn-ing situations, involving veterinarians (provided theyare able to work at the herd-health level, respect theindividual farmer’s goals, and understand the princi-ples of organic farming), or to dissolve the group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The farmers participating in the project are grate-fully acknowledged for carrying the process with suchan open-minded attitude and enthusiasm throughoutthe project, and the great hospitality and communica-tion. Our colleague, Willie Lockeretz (Tufts University,Boston, MA), is gratefully acknowledged for valuablesuggestions to improvements of an earlier version ofthis manuscript.

REFERENCES

Anonymous. 2003. Farmer Field Schools. The Kenyan Experience.Report of the Farmer Field School stakeholders’ forum, Int.Livest. Res. Inst., Nairobi, Kenya.

Bennedsgaard, T. W., S. M. Thamsborg, M. Vaarst, and C. Enevold-sen. 2003. Eleven years of organic milk production in Denmark:Herd health and production in relation to time of conversion andcompared to conventional production. Livest. Prod. Sci.80:121–131.

Boud, D., R. Keogh, and D. Walker. 1985. Promoting reflection inlearning: A model. Pages 18–40 in Reflection: Turning Experienceinto Learning. D. Boud, R. Keogh, and D. Walker, ed. Kogan PageLtd., London, UK.

Bourdieu, P. 1990. In Other Words. Essays Towards a Reflexive Soci-ology. Polity Press, Cambridge, UK.

DARCOF. 2000. Principles of organic farming. Discussion documentprepared for the DARCOF Users Committee. Danish ResearchCentre for Organic Farming (DARCOF), Tjele, Denmark.

Journal of Dairy Science Vol. 90 No. 5, 2007

Hovi, M., D. Gray, M. Vaarst, A. Striezel, M. Walkenhorst, and S.Roderick. 2004. Promoting Health and Welfare through Planning.Pages 253–278 in Animal Health and Welfare in Organic Agricul-ture. M. Vaarst, S. Roderick, V. Lund, and W. Lockeretz, ed. CABIPublishing, Wallingford, UK.

Khisa, G. S. 2003. Overview over the Farmer Field School approach.Pages 3–10 in Farmer Field Schools. The Kenyan Experience.Report of the Farmer Field School stakeholders’ forum, Int.Livest. Res. Inst., Nairobi, Kenya.

Klaas, I. 2006. Development and application of systematic clinicaludder examinations as supplementary tool in udder health as-sessment. PhD Diss. Department of Large Animal Sciences, TheRoyal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Denmark, and De-partment of Animal Health, Welfare and Nutrition, Danish Insti-tute of Agricultural Sciences, Research Centre Foulum, Denmark.

Klaas, I., M. Vaarst, T. W. Bennedsgaard, and S. Østergaard. 2006.Udfasning af antibiotika i danske besætninger—resultater fraThise projektet [Phasing out antibiotics from Danish herds—results from the Thise-project]. Pages 114–115 in Proc. DanishOrganic Congr. 2006, Odense, Denmark. Danish Research Centrefor Organic Farming, Tjele, Denmark.

Kvale, S. 1996. Interviews. An Introduction to Qualitative Research.Interviewing. Sage Publications, Thousands Oaks, CA.

Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated learning: Legitimate periph-eral participation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Olsen, A. B. 2006. Mine erfaringer med staldskoler og udfasning afantibiotika. [My experiences with Stable Schools and phasing outantibiotics]. Pages 116–117 in Proc. Danish Organic Congr. 2006,Odense, Denmark. Danish Research Centre for Organic Farming,Tjele, Denmark.

Rasmussen, J. B. 2005. Færre end 200 nye kvægstalde i 2004 [Lessthan 200 new cattle housing systems in 2004]. Info- Byggeri ogTeknik. Nr. 1409. http://www.lr.dk/bygningerogmaskiner/informationsserier/info-byggeriogteknik-gratis/1409_jbr.htm Ac-cessed Oct. 18, 2006.

Skjøth, F., A. M. Keldsen, and M. Trinderup. 2005. Landbrugsinfo—kvæg—tal om kvæg [Farming Information > Cattle > Figures].http://www.lr.dk/applikationer/kate/viskategori.asp?ID=ka004000080001401 Accessed Oct. 18, 2006.

StatBank Denmark. 2006. Detailed statistical information on theDanish society. http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1280 Accessed Oct. 18, 2006.

Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research.Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage Publications,Thousands Oaks, CA.

Vaarst, M. 2006. Farmer stable schools: A fruitful way for Danishorganic dairy farmers with the goal to phase out antibiotics fromtheir herds. Pages 64–68 in Changing European farming systemsfor a better future. New visions for rural areas. H. Langeveld andN. Roling, ed. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen,the Netherlands.

Vaarst, M., D. K. Byarugaba, J. Nakavuma, and C. Laker. Participa-tory livestock farmer training for improvement of animal healthin rural and peri-urban smallholder dairy herds in Jinja, Uganda.Trop. Anim. Health prod. (accepted)

Verhoog, H., V. Lund, and H. F. Alrøe. 2004. Animal Welfare, Ethicsand Organic Farming. Pages 73–94 in Animal Health and Welfarein Organic Agriculture. M. Vaarst, S. Roderick, V. Lund, and W.Lockeretz, ed. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, UK.