Dakota Life 1 16 2015

-

Upload

wick-communications -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Dakota Life 1 16 2015

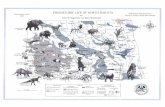

Dakota Lifevisit us at www.capjournal.com • e-mail us at [email protected] Friday • 1.16.2015

Finding the sweet in a bitter eraBy Lance [email protected]

To spare the butter and save your eggs and spare the milk, what you ought to bake for your family is some of that Depression Cake.

But good luck getting it exactly right. Some say the very best Depression Cake is made on an old wood-fired range that burns driftwood and downed timber like you used to find in the Oahe Bottom, but to get to one of those smoky kitchens in this day and age is not easy. You can try taking the road north of Pierre as though you’re going to Peoria Flats, but you’ve got to go way further back than that – turn left at the 1940s, watch for the turn for the 1930s. But if the road to those old decades is under water, just stop and ask directions. Stop and ask Loretta Cowan.

She’ll tell you all about it.She might even share the

recipe.

“My Dad’s family grew up at Canning. I went to first grade in Canning School and that year Mom and Dad moved up into the Oahe Bottom. So that was probably 1946, I suppose,” Loretta Cowan tells you in a house that’s now perched on the bluffs above Lake Oahe. “It always kind of rubs me the wrong way when they call it ‘Peoria Flats,’ because that is a mod-ern-day term for it and the Oahe Bottom was the river bottom, you know – the valley that was created by the Missouri River. And the ‘Peoria’ came because it’s Peoria Township. It was always called ‘the Oahe Bottom.’ Peoria Flats is another bench higher than the bottom was.”

There was some thought that someone had named Peoria Flats for the town of Peoria, Illinois, but Cowan said it’s more likely that it was named for a Missouri River steamboat that plied those waters, the Peoria Belle.

There’s a portrait from the Miller studio in Pierre taken about that time that shows Art and Helen Metzinger and four of their kids, Deenie, Judy, Janet and Loretta.

“It had to have been taken the year they moved up into the river bottom. And then they had six more kids,” Loretta says.

A little girl’s view of Utopia

“When we lived in the river bottom, when you went up on the flat and then you dropped back down to the river was what we called ‘Fielder

Bottom.’ There were people that lived in that area, too.”

And there was also ‘the Little Bend’ that you’d hear the big people talk about. But if you were just a kid fresh out of first grade you didn’t worry about all the names for things when you first came down to live in the bottom. You had other things to think about.

“We loved it. It was wonderful. I think Mom and Dad were so happy there – Mom said it was ‘Utopia.’ It was so differ-ent from the prairie, she always said, because of the trees and the woods and the river and the ani-mals that they saw that they didn’t see on the prairie,” Cowan said.

There were trees that would fall in the river bottom that were near as big across as a little girl was tall, and big peo-ple would cut them into lengths and you could sit on them; and there were old log buildings that other people had made long before – peo-ple said they were made by Harney’s troops when they needed winter quar-ters in the river bottom. And there were floods in 1947 and ‘50 and ’52 that came up even around grand old buildings like the Oahe Mission and the Riggs mansion away off across the flat of the plain. Sometimes the big people had to use a trac-tor or a boat to get across water, and sometimes they had to use a boat to chase your horses to higher ground.

And your mom grew tomato plants and water-melons, and sent you to Grandview School, and taught you all kinds

of things that she’d learned from Grandma Sherwood, her mom. But some of them Grandma actually had learned from the government, oddly enough; because the government had a different way of dealing with people at that time.

You understood all that after a while. The government had set up a land-grant university system to teach agri-culture and mechanical arts in every state way back in 1862 when Abe Lincoln was the presi-dent, and after that it had organized agricultural experiment stations in 1887 to make better crops and cattle and figure out better ways cook and sew and make canned goods from the things you grew. And then finally the government built a Cooperative Extension service in 1914 – 101 years ago now – to extend that knowledge of the land-grant universities out to the people. And the university did extend all that learning – including the knowledge of how to bake Depression Cake.

A Helping HandLoretta Cowan isn’t

exactly sure how the rec-ipe came into the family.

“I am not sure if it came from Mom or if she might have gotten it from her mother, Grandma Sherwood. It was some-thing they put out dur-ing the Depression. They had leaflets that they put out. From the Extension I think probably is where some of those things came from – from the Extension office.”

There was sound thinking behind that idea of Depression Cake.

“It has no butter, eggs or milk in it, so that let the people make some-thing that was a sweet thing without using the things that they could sell at the grocery store or the creamery or what-ever. It didn’t take away from their livelihood. They could sell their eggs and sell their milk and sell their cream.

“I could see the pur-pose of it. We spent a lot of time with Grandpa and Grandma. That was their grocery money. They sold cream and sold eggs and even sold the chickens. Grandma always got chickens in the spring and sold spring fryers.”

The government and the land-grant university

people had even set up a way to get that knowl-edge out into the rural neighborhoods.

“Grandma belonged to the Helping Hand Club. Grandpa and Grandma lived in DeGrey at that time. It was an Extension club they had at that time in that area,” Cowan

Recipe for hard times

Clockwise from Top: The Metzingers’ house in the Oahe Bottom, where the family lived from 1946 until they bought a house in Fort Pierre in 1958 as Lake Oahe began filling the river bottom.

Four of the Metzinger children on a fallen tree that toppled in about 1948.

In 1959, the Metzingers and neighbors such as the Robinsons watched water from newly formed Lake Oahe swallow up farmsteads.

Art Metzinger and a neighbor fording high waters from spring snowmelt with a tractor. Flooding caused by ice jams would routinely back up about farmsteads in the Oahe Bottom. (Photos courtesy of Loretta Cowan)

See Recipe, C6

Dakota Life Friday, January 16, 2015capjournal.comC6

said. “It was a social event when you had ‘club’ at your house. You prepared, you painted, you got new curtains.

“You usually had a demonstration on how to cut up a chicken or things like that or a sew-ing-type thing. They paid dues. I think Grandma said the dues were 15 cents or something – it was small. Then when they had club, a lot of times the men drove the women and then they vis-ited while the women had their club meeting. And then of course all the kids came. It was quite a houseful, usually on a weekday.

“The women were stay-at-home moms com-pared to today’s women. They worked, but not outside the home – well, except for milking cows or working in the field.”

Loretta Cowan has her Grandma Sherwood’s diaries, and sometimes Grandma wrote that there were 40 people at her house when the Extension club met.

“It was, for some of those people, hard times,” Cowan said.

And that was the gov-ernment in action in those days – how to spare the butter and save the eggs. Which was infor-mation you could use to live a little better in the 1930s; or even if you were just a daughter learn-ing from your mother in the 1940s; or if you were a granddaughter like Loretta Cowan, studying your grandmother’s reci-pes in the 1950s.

The recipeShe learned that to

make Depression Cake you need:

2 cups brown sugar2 cups water2 cups raisins2 tablespoons lardBoil 5 minutes. Cool.

Then add:1 teaspoon soda1 teaspoon salt1 teaspoon cinnamon1 teaspoon nutmeg½ teaspoon cloves3 cups flourBake 30-35 minutes in

an ordinary cake pan at 350 degrees.

The frostingAt least in the Cowan

family, the frosting was always the recipe they picked up from some members of the Hyde family of DeGrey through the Hughes County 4-H Cookbook.

To make an easy cara-mel frosting, the things you need are these:

½ cup butter1 cup brown sugar¼ cup milk1 ¾ to 2 cups powdered

sugarMelt butter, add 1 cup

firmly packed brown sugar and cook over low heat for 2 minutes, stir-ring constantly. Add ¼ cup milk and cook and stir until mixture comes to a boil. Remove from heat. Cool. Add enough pow-dered sugar until of right consistency.

Picnic CakeAnd there were some

variations; like what

Loretta Cowan’s mother, Helen Metzinger, did.

“She used it as a base for fruit cake – she would add the candied fruit and nuts to it and use it as a base for fruit cake because it was moist and kept good. She’d wrap it up. She usually make it about, oh, Thanksgiving, and wrap it up with foil and put it in a cool, dark place and then you had fruit cake for Christmas. I still make it at Christmas time. She used to make it in an angel food cake pan and make a big one.

“When she made it in just a standard cake pan, without the fruit, we always called it ‘the picnic cake.’ She always made it for picnics because it was a good cake to haul.”

And there were lots of places you could picnic then – living in Utopia.

“You hear it said quite often: ‘We were poor but we didn’t know we were.’ Nobody else had anything more than you did.”

And just to have good neighbors, there was a kind of wealth in that. As the Metzinger family could see in a year such as 1953.

“Dad got real sick and had emergency surgery and then couldn’t work – there was hay to be brought in, it was late summer. The neighbors and family and every-body hauled his hay in and of course in those days it was done in a hay rack. And then later I think someone came and cut silage for him.”

Lake OaheBut so many things

have gone under water now.

The government want-ed to build a big dam a few miles south and flood the whole Missouri River Valley after the Pick-Sloan Act of 1944 went through Congress. And when it came time to build it, the federal government taught the people in those neigh-borhoods another lesson – about property. Under threat of condemnation,

the Metzingers signed an option to sell their land at $30 an acre in October 1954. There was never any compensation for their gravel that helped sur-face the face of the dam, but the Corps told them later in a letter that it wouldn’t have enhanced the value of the property, anyway.

“I think what really sticks in most people’s craws was the compensa-tion, and that the Corps of Engineers declared it was just wasteland, it was no good for any-thing,” Loretta Cowan remembers. “Well, for heaven’s sake, it was the best winter country we had, the woods and the valleys.”

The people in the Oahe Bottom got to experience that kind of river politics first.

“We were the first bunch. And it wasn’t that many years till they started taking the land for the Big Bend. And so those people in those areas had learned, Yes, you could fight the Corps of Engineers and the U.S. government. So they were a little better com-pensated.

“I guess growing up and even in my early adult life, I thought that you did not fight the IRS and the Corps of Engineers – to do so was kind of like a sin against God or something. I think I wasn’t the only person who felt that way. You just accepted what they said, you really had no voice in the matter. Well, you do.”

Her parents and the neighbors fought it; espe-cially her mother.

“They did form a land-owners association and she did testify at hear-ings. She wrote a ton of letters.”

The Metzingers real-ized later the dam had to be in the making already about the time they moved down into the Oahe Bottom, maybe even before.

“They were doing sur-veying even in ’45 and ’46 and taking soil samples,” Cowan said. “Dad always said he wished he would have just shot the first son of a bitch that came on the land. I don’t think that would have solved anything. Mom was a lot more vocal than Dad was – of course his methods might have been a little more extreme than hers were. “

They lived in the Oahe Bottom from 1946 until they had to get out in 1958.

“When they finally moved out of the bot-tom and they bought a house in Fort Pierre, they were always looking for another place that they could move to. Nothing ever measured up to what they had before.”

No; because there was no place like that Utopia they’d found down by the river.

“They finally found a place south of Blunt and they moved there. And they were hardly there when they started the Oahe Project to dig the

big ditch that went clear across that they could irrigate out of.”

By then the Metzingers were so used to fighting the government that they fought that project, too. And this time they won.

“They fought that then because it was going to come right through their land. That’s one of the few things that they ever got stopped.”

They were part of United Family Farmers and they testified at the Oahe Subdistrict hear-

ings in Blunt about the land acquisition prac-tices of the Bureau of Reclamation and the Corps of Engineers, and in the end, they helped get the irrigation project traded for rural water projects.

“Everybody needed good water,” Loretta Cowan said.

Everybody still needs good water.

If you’re making Depression Cake, you’ll need at least two cups.

Some say Missouri River water is best.

XNLV

1342

01

XNLV193567

BO

OK

SIG

NIN

G MICHELLE RAYWednesdayJAN 21, 4-6PM

BO

OK

SIG

NIN

G

www.michelleray.com

wwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww....mmmiimimicccichhhhcheeeelllll yyy

321 S. PIERRE ST | 945-1100

lllll o

Born in Australia and now residing in Vancouver, Canada, leadership expert and author, Michelle Ray, is an award-winning speaker and founder of the Lead Yourself First Institute.

Top: Helen Metzinger tending her flock of turkeys in 1948 next to a log cabin in the Oahe Bottom. The log house was said to have been built by Harney’s men for winter quarters due to poor conditions farther south near Fort Pierre.Bottom: Driving horses to higher ground with a boat in the 1950 flood.

RecipeFrom C1