Cutting Edge: Contemporary Africa in the etchings of Mario ...€¦ · Mario has lived) as well as...

Transcript of Cutting Edge: Contemporary Africa in the etchings of Mario ...€¦ · Mario has lived) as well as...

Cutting Edge:

Contemporary Africa in the etchings of Mario Soares

“I don’t like to make portraits because my spirit feels like I’m not doing my work. My work, I like it to be very busy.”

Looking at Mario’s prints, one gets the feeling of having found an old photograph in a family album. The viewer gets the sense of having been there, and having known them, when faced with the subjects and spaces that are composed within the etchings. This owes much to the artist’s careful capturing of both the minute details of urban South Africa and Mozambique (two countries in which Mario has lived) as well as

the feeling of the scenes which he depicts. Bustling cosmopolitan squares, loud markets and traffic-ridden highways are episodes Mario is drawn to, and it isn’t difficult to see why.

Mario started making art at the age of six, in Mozambique, drawing as frequently, and in as many way he could. For him art and education were the pillars of his childhood, occupying an even amount of importance, and deserving an equal amount of time. When he was eighteen, Mario joined a circle of artists in his home town, a lively body of talented painters who would inspire one another and share ideas. This laid the foundation for Mario’s relationship with local artistic groups, to which he would find himself drawn throughout his entire career.

In 2008, Mario moved to South Africa, finally leaving painting and Mozambique behind. Joining Artist Proof Studio in Johannesburg, the artist began experimenting with printmaking, and found that the medium offered him what he had been looking for. Mario still works in print, specialising in etching on steel plates, a technique which the artist operates with remarkable technical skill to achieve masterly finesse.

In Heroes’ Square (Maputo) Mario looks at his time in Mozambique. We see a scene scattered with faceless market-goers, the facades of shops in the right and left portions, and a plethora of trees lined up in uniform in the farthest point of the landscape. Amidst the anonymous bodies and nondescript architectural fragments, the artist

has positioned an intriguing portrait of a young man. Placed in the corner of the frame, he looks at the viewer, acknowledging their presence and gazing back in a confident, if daring gesture. Almost worthy of being an entire composition of its own, the portrait reckons with the boundaries between the unknown and the familiar, attesting to an intimate relationship which has managed to break the motion that engulfs the entire image.

Asking the artist about his subject matters, Mario states that “[I] don’t like to make portraits because my spirit feels like I’m not doing my work. My work, I like it to be very busy”. His compositions are mostly bound to spaces, rather than people, although I think that the two

are almost indistinguishable in his work. The streets are people-like, alive and full of noise. “I am looking at the movement” says the artist, movements enacted onto the streets in such regularity, that they seem to have compressed kinetic energy in themselves, finally springing outwards. Yet the action is not imposing, nor frightful, but rather comforting, like white noise that for a moment makes you think that the streets are humming after being mute for so long. Sound, movement and space are forces that build up the familiar, in Mario’s prints, a familial conversation between the image and the viewer. The cityscapes are almost formed as noisy portraits, subjects in their own way, and Mario’s prints capture their peculiar, urban subjectivity.

The artist works always from photographs. After capturing a scene, and reducing the colour palette to black and white, Mario begins etching onto his plate. Working from one photograph at a time, he does not mix multiple compositions, nor digitally warp the single image in any way. “But” says Mario, “I am very playful”. When transferring the image onto the plate the artist admits that “I like to play with what I see in the photograph”, allowing the final image to be indexical to his vision, bound to the physical world, its sensorial reception, and the imagination that navigates these thresholds. After all, says Mario “I cannot make the product without the photograph, but I also cannot make it without my mind”.But what is in Mario’s mind is beyond playfulness and urban noise. The artist is interested in the potential of the medium of print to

address the translucent politics of inequality, a haunting vestige that clouds the cities he carves into his plates. In Mozambique, the artist had “seen a lot of people working very hard for a better future, a better life”, a pattern he notices in contemporary South Africa. Having lived through poverty himself, the prints retain an embodied spectatorship, one in which the artist sees problem out-there on the streets, signs that may easily be ignored without the aid of Mario’s diacritics.

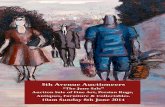

In his 2017 print Even People of Johannesburg Still Fight Against Poverty III, the artist addresses the abidance of structural inequity through the body of localised urban life. Seen from the position of a heightened vantage point, the viewer is allowed access into the particular happenings of a cityscape that at first overwhelms, before fitting

together like pieces of a puzzle. Mario’s layering of vehicles on people (and people on vehicles) signals the aura of Johannesburg as a noisy space where mouths and machines seem in competition with one another. This is not, however, a merely pictorial gesture, nor an empty metaphor. For Mario, this is the mode through which the layered, and layering, politics of class and economy may be parsed. On the one hand, by drawing attention to the populace who flood highways, pavements and cars, Mario reduces the human body to the labour-force that it signifies in the brutal capitalist mechanism. At the same time, the attention to activity and movement attest to the protraction of resistance activated daily by these bodies who exist in a system that consumes their subjectivity.

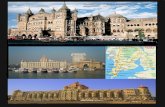

ImagesPage one—Day To Day Of People of Johannesburg (2017), and detail from Heroes’ Square (Maputo) (2018)Page two— Heroes’ Square (Maputo) (2018)Page three— Even People of Johannesburg Still Fight Against Poverty III (2017) Page four— Faraway II (2018)

As politically sharp as his commentary is, there is something, I think, in Mario’s work that hints to the hopeful. Mario has recently opened his own studio in Parkhurst, Johannesburg (a stone’s throw from Guns & Rain) to make way for young talented artists to have access to specialised printing equipment. He claims that he wants to collaborate “with other talented people who have their talent but do not have access to resources”. Mario not only wants to establish his practise in South Africa, but also to bring equipment to Mozambique where he believes are young people who need printmaking. This lays beneath the surface in works such as Faraway II, where the artist carefully renders each individual with precision. A face from profile, a turned head, an ear or a neck marks each subject mimetically, and almost with photographic attention, breaking down the dizzy movement and anonymity that in the other works feel incapacitating, or so familiar it renders inactivity. The people in Faraway II have not moved beyond the capitalist market (we see plastic bags), but are neither consumed by it. Representing the existence of the individual within the collective, Mario attests that there is space amidst the deafening noise for hopeful chants. In these moments, the prints become stages in

which to immortalise the working-class and grant them subjectivity, while looking forward to a time in which their hopefulness can assume life outside of Mario’s printed borders.

—Kayra Uguz

Learn more of Mario's work at Guns & Rain, www.gunsandrain.com