Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535...

-

Upload

tameka-roberts -

Category

Documents

-

view

229 -

download

0

Transcript of Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535...

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 1/134

Cult and Continuity

A religious biography of the Maltese

archipelago from the Neolithic up till 535 CE

J.L. van Sister

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 2/134

Cover image: Statue of a female deity, originating from Malta (Bonanno 2005, 163).

Name: J.L. van Sister

E-mail: [email protected]

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 3/134

1

LEIDEN UNIVERSITY

Cult and Continuity

A religious biography of the Maltese

archipelago from the Neolithic up till 535 CE

J.L. van Sister

15/12/2013

S0912395

MA Thesis; ARCH 1044WY

Supervisors: Dr. M.J. Versluys and Dr. H.H. Stöger

Classical and Mediterranean Archaeology

Leiden University, Faculty of Archaeology

Leiden, 2013

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 4/134

2

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 5/134

3

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 6 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 7 2. History of Malta ............................................................................................................ 13

2.1 Prehistoric developments ....................................................................................... 13 2.1.1 The Early Neolithic phases .............................................................................. 14 2.1.2 The Temple Period ........................................................................................... 15 2.1.3 The Bronze Age ............................................................................................... 20

2.2 Proto-historic phases .............................................................................................. 22 2.2.1 Arrival of the Phoenicians ................................................................................ 23 2.2.2 Influence from the West ................................................................................... 24

2.3 Roman Period ......................................................................................................... 27 2.3.1 Roman Conquest; Malta under the Republic ................................................... 27 2.3.2 Imperial Malta .................................................................................................. 28 2.3.3 Late Antiquity .................................................................................................. 30

3. Theoretical discussion ................................................................................................... 33 3.1 Critical review of Malta’s historical chronology ................................................... 33 3.2 Reconstructing religion ........................................................................................... 34

3.2.1 Discussing and recognising religion ................................................................ 34 3.2.2 Defining concepts............................................................................................. 36

3.3 Cultural universalism or relativism? ....................................................................... 39 3.3.1 Mediterraneanism ............................................................................................. 39 3.3.2 A question of identity ....................................................................................... 40 3.3.3 Insularity .......................................................................................................... 41

4. Prehistoric island cult .................................................................................................... 43

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 6/134

4

4.1 Early evidence for ritual activities .......................................................................... 43 4.2 Cult during the Temple period ................................................................................ 46

4.2.1 Function and use of the temples ....................................................................... 47 4.2.2 Burial customs .................................................................................................. 53

4.3 A break in traditions ............................................................................................... 55 5. Growing connectivity and influence of city-states ........................................................ 57

5.1 'Phoenician' religious developments ....................................................................... 57 5.1.1 Epigraphic evidence for religious activity ....................................................... 58 5.1.2 Continuity in cult locations: Phoenician temples ............................................ 59 5.1.3 Burial customs .................................................................................................. 61

5.2 The Hellenising and Punic influence on religious developments ........................... 63 5.2.1 The continuation and erection of cult locations ............................................... 63 5.2.2 Recognising the deities .................................................................................... 67 5.2.3 Mortuary customs............................................................................................. 69

5.3 Apotropaic amulets ................................................................................................. 72 6. Malta under Roman hegemony ..................................................................................... 75

6.1 Clinging to old traditions (218 BCE to the 1stcentury BCE) .................................. 75 6.1.1 Votive inscriptions ........................................................................................... 76 6.1.2 Syncretism on coins ......................................................................................... 77 6.1.3 Continuity of cult locations .............................................................................. 81

6.1.3.1 Tas-Sil ..................................................................................................... 81 6.1.3.2 Ras-Ir-Raeb ............................................................................................. 81 6.1.3.3 Ras Il-Wardija ........................................................................................... 82

6.2 A time of change (1st century BCE-Late Antiquity) ............................................... 85 6.2.1 Evidence for religious developments ............................................................... 85 6.2.2 Presence of 'Eastern' cults ................................................................................ 88

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 7/134

5

6.2.2.1 Isis and other Egyptian deities .................................................................. 88 6.2.2.2 Mithras ...................................................................................................... 91

7. Palaeo-Christianity and Judaism on the islands ............................................................ 95 7.1 The Jewish community on Malta ............................................................................ 95 7.2 Palaeo-Christianity ................................................................................................. 99

7.2.1 Early Christian cult locations ........................................................................... 99 7.2.1.1 Tas-Sil ..................................................................................................... 99 7.2.1.2 San Pawl Milqi ........................................................................................ 101

7.2.2 Hypogea ......................................................................................................... 103 8. Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 109

8.1 Synthesis of the 'Religious biography' .................................................................. 109 8.2 Possibilities for future research............................................................................. 114

Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 117 List of figures .................................................................................................................. 119 Literature ......................................................................................................................... 123

Primary Sources .......................................................................................................... 123 Regular Sources .......................................................................................................... 123 Online sources ............................................................................................................ 132

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 8/134

6

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my thanks to Dr. Versluys for accepting to be my thesis supervisor

and for believing in me and trusting me. I also would like to thank Dr. Stöger for her

continuous support while writing the thesis and the effort she put in reading it and

commenting on it. By constantly challenging me and the work written she pushed me to

go further and often gave me the encouragement I needed.

My sincere thanks go to Prof. Dr. Anthony Bonanno and Dr. Nicholas Vella, both from

the University of Malta, Department of Classics and Archaeology. Both of them showed

great support and help when I asked them for assistance. Without them I would have not

have been able to access some very vital sources.

Further gratitude is owed to Heritage Malta for allowing me to use some of their images

and photos in this publication and for allowing me access to the site Tas-Sil in January,

after I handed in this thesis. Thanks to Louis Vella for sending me some of his photos of

objects I studied and allowing me to use them.

Finally I would like to thank my beloved. Without her constant support I would not have

been able to finish. Her remarks after reading chapter drafts were insightful and

stimulated me to once more go through everything.

Thank you.

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 9/134

7

1. Introduction

This study is concerned with the ‘religious biography’ of the Maltese islands from a long-

term perspective. This research analyzes the islands’ religious development in terms of

the (dis)continuity of religious activities from the Neolithic period until the incorporation

of Malta into the Byzantine Empire in 535 CE. This study will focus on the period before

the islands' incorporation into the Byzantine Empire, so as to include the early forms of

Christianity and the end of the Roman Empire, a clearly defined temporal scope and still

a period large enough to be able to recognise patterns. This temporal approach will

identify and explain diverse religious traditions, as well as highlight regional

developments through the continuous use of select cult sites as well as the associated

cultic practices.

The Maltese archipelago, located to the southeast of Sicily, lies well situated in the centre

of the Mediterranean (figure 1.1). While the Maltese islands only cover 314 square

kilometers (Malta 243 km2, Gozo 69 km2 and Comino 2 km2) (Trump 1972, 13-15), a

remarkably diverse history and high levels of connectivity between the islands and other

regions are observable. Owing to their geographical location, the islands were subject to

many different cultural and political encounters, ranging from economic exchange to

fully-fledged colonial domination. From the Early Neolithic until modern times the

islands have been home to a great number of different people, ushering in different

cultural phases, which are often chronologically distinct and clearly reflected in the

islands’ material heritage. During this extensive period, from the Neolithic to the

Byzantine era, many different influences from various geographical regions and diverse

political systems affected the religious activities on the islands.

Figure 1.1: Map of the Mediterranean showing Phoenician trade routes (Bonanno 2011, 39).

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 10/134

8

The Neolithic stone complexes, which number more than 30, have been described by

Colin Renfrew as the 'earliest free-standing monuments of stone in the world' (1973,

147). These megalithic buildings, referred to as temples, have been explored intenselyfrom different perspectives, ranging from discussions about aspects of prehistoric cult

(e.g. Barrowclough and Malone 2007) to studies into the material culture. The latter

studies were conducted to draw inferences about Malta’s connectedness with the wider

Mediterranean (van Dommelen and Knapp 2010, 5). Although diverse assumptions exist

concerning the religious nature of these Neolithic structures, recent efforts have

deconstructed earlier simplistic views about the so-called temples and the associated

Neolithic belief systems (Barrowclough and Malone 2007; Trump 2002).

Malta continued to be a place of importance during the first Millennium BCE, when sea-

faring activities intensified throughout the Mediterranean. The archipelago was then a

prime strategic location between not only north and south, but foremost between the

eastern and western Mediterranean. During the Punic Wars, Malta was a sought-after

military outpost, prompting Roman sources to specifically name (and date) the moment of

conquest in 218 BCE (Livy, 21, 51, 1-2). After Malta had been under Roman rule, the

islands witnessed a period of Byzantine occupation, followed by a sequence of foreign

domination, including Muslim and Frankish rule, as well as a number of subsequent

ruling powerhouses of the Mediterranean and beyond (Aragon, The Knights of St. John,

the French and finally the British), until Malta eventually gained independence in 1964.

This rich exposure to cultural diversity, accumulated over time, makes the islands a

suitable case study to investigate the correlation and the interplay between insularity and

connectivity and more specifically, the effect these forces had on religious developments,

taking into account the local impact and the influences from outside.

Previous studies have looked at various aspects of Malta’s religious landscape mainly in

isolation or by time period. This study has the stated aim to achieve a synoptic approach

pursued from a long-term perspective. Therefore the main research question posited by

this study is: How have the influences of connectivity and insularity, two seemingly

opposing forces, influenced and shaped the religious developments occurring on the

Maltese archipelago from the Neolithic until the beginning of the Byzantine period

in 535 BCE?

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 11/134

9

In order to answer this question this research will examine the development of religious

activities over time with specific attention to breaks and/or continuity in cult location,

ritual practice and venerated deities. By focusing on various aspects of cult location, ritualpractice and prevalent or specific divinities, this study seeks to identify patterns of

continuous tradition, adaptation, assimilation, or new beginnings. Naturally, such an

expansive chronological range can only allow for an exploratory rather than an

exhaustive examination of religious phenomena. The dataset explored is derived from the

extensive corpus of publications dealing with the prehistory and history of the Maltese

archipelago and no unpublished material will be discussed in this thesis.

The combined results of this study will construct the religious biography of the Maltese

islands, describing chronologically the development of religious activities, as well as the

presence and absence of certain cults. In compiling this religious biography, the main

focus is on the continuity of religious activities throughout different periods, as well as

any cultural and societal information (e.g. indications for trade or social stratification)

that can be gleaned from these investigations into the material evidence of religious

practice.

The study of the development of religion and ritual allows insights into the cultural

interactions and may therefore help to understand the development and cultural character

of the Maltese islands within a larger geographical and political context. The analysis of

several continuous aspects of religion, such as rituals and cult locations, can help to

comprehend better how these phenomena developed. By discussing not only one period

(e.g. prehistory), but multiple periods, long-term patterns of continuity can be recognised

and the developmental stages of persisting traditions can be recognised appropriately. A

complete overview of religious developments for these rich and varied Mediterranean

islands has never been achieved, while separate chronological phases or religious

phenomena have been studied extensively and only several cult sites (such as Tas-Sil)

have been studied diachronically. An earlier study to understand cult through the material

culture has been conducted for the prehistoric period, with a specific focus on the

contextualisation of ritual in the archaeological heritage of Malta (Barrowclough and

Malone 2007). The Phoenician, Punic, and Roman periods have been studied by Anthony

Bonanno and others, while the evidence for early Judaism and palaeo-Christianity has

been analyzed by Mario Buhagiar. This study will thus contribute to a more

comprehensive understanding of Malta’s religious development by covering all of these

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 12/134

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 13/134

11

continuity. Chapter Six covers the period from 218 BCE until Late Antiquity, examining

religious changes during the era of Roman rule. The introduction of new cults and the

development of already established cults are the subject of this chapter, followed by acritical assessment of the presence of mystery cults on the islands. Chapter Seven

concentrates on the evidence for Christian and Jewish activities on the islands until 535

CE, effectively covering the last period studied in this research.

Chapter Eight, the concluding chapter, synthesises what has been argued for and

achieved in this thesis. Conclusions drawn and observations made while studying the

evidence for religion during continuous temporal phases, assessed in the light of the

theoretical discourse pertaining to insularity and connectivity, are presented, which thus

chart the island’s religious biography. Periods of increased religious influence due to

connectivity can be witnessed on several occasions in Maltese history, when we see the

appearance of new religious phenomena on the islands. With the exception of the hiatus

in the Bronze Age, there is however an overall continuity visible in the development of

religion. New and old traditions are selectively maintained or adopted and this is reflected

in both the continuity of cult sites and the syncretism of several deities. Finally, the

concluding chapter points out the areas where future research can provide more clarity.

Those areas in Malta's religious landscape, which are very unclear at the moment, should

be examined in the future.

During this large-scale research into this complex subject matter, what will be lost in

details will hopefully be gained in long-term overview.

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 14/134

12

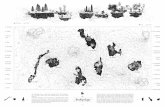

Figure 1.2: Map of the archipelago showing archaeological sites and locations (Bonanno 2005, 282-283).

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 15/134

13

2. History of Malta

This chapter will outline the history of the Maltese archipelago from the Neolithic period

until the incorporation of the islands into the Byzantine Empire in 535 CE. This outline

will provide the chronological framework for the cultural developments which will be

discussed in the following chapters. The chronology presented here follows the work of

established scholars in Maltese archaeology. The timeframe will be presented within the

context of the connections between the islands and the areas of the Mediterranean from

where new people and new cultural influences hailed from. The influences resulting from

these connections, combined with the effect of the insularity of the Maltese islands are at

the core of this thesis and will be explored through the islands’ religious biography. It is

vital for the understanding and contextualisation of the religious developments covered in

the following chapters to have discussed the cultural complexities of the past and their

characteristics (figure 2.1).

2.1 Prehistoric developments

Figure 2.1: A chronological overview of cultural sequences in Malta (Fenech 2007, 37, figure 3.1).

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 16/134

14

2.1.1 The Early Neolithic phases

The early prehistory of the islands can only partly be reconstructed, as there are not many

archaeological sources available for this period of human occupation. The earliest known

evidence for human presence comes from Gar Dalam, a cave site in the area of

Birzebbuga in the southeast of Malta. The cave deposits yielded shards of pottery (Trump

2002, 28). Għar Dalam (5500-4100 BCE) thus became the type site for the earliest

period of human activity on the Maltese archipelago, marking the beginning of the

Neolithic (Driessen 1992, 28-39; Stoddart et al. 1993, 6; Trump 2002, 28). A number of

other sites have yielded Gar Dalam pottery, one of which is Skorba, the type site for the

next following periods.Gar Dalam

pottery has been dated to approximately 5000 BCE,

based on the radiocarbon dates of a sample from Skorba (5266-4846 BCE). The pottery

shares stylistic similarities with the Sicilian Stentinello ware, which lead to the theory that

early settlers came from this area (Driessen 1992, 29; Fenech 2007, 37; Stoddart et al.

1993, 6).

The earliest society seems to have been fully agricultural, a conclusion drawn from the

absence of small game (possibly extinct as a result of the early colonisation), and

restraints imposed by the islands’ biogeography. Agricultural production, as well as a

constant influx of new people, was necessary due to the limited natural resources offered

by the island (Stoddart et al. 1993, 6; Trump 2002, 23-30).1 These people, possibly the

first settlers, brought with them domesticated animals, including cattle, sheep, goat and

pigs, as learned from evidence obtained from excavations at Skorba (Fenech 2007, 38).

During the Gar Dalam phase (Fenech 2007, 37) the early population utilised natural

caves for domestic purposes, but there is also evidence for the use of huts near the site of

Skorba, where also traces of a long wall have been uncovered (Trump 2002, 32-33).

The next two phases of Maltese prehistory have both been named after the type site

Skorba, and are mostly based on stylistic differences in pottery. The later Gar Dalam

wares seem to foreshadow already the succeeding Grey Skorba wares (4500-4400 BCE),

thereby pointing to a seamless continuity in the succession of these phases (Trump 2002,

1 It is beyond the scope of this research to completely cover the discussion about the early colonisation of the

archipelago. For more information on this discussion, see Trump 2002.

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 17/134

15

47-48). The Grey Skorba phase is solely distinguished on the basis of ceramic typology,

since no carbon dates have been established for this period. Directly developing from the

Grey Skorba wares is the Red Skorba style (4400-4100 BCE), which is similar to thecontemporary red slip Diana wares from Sicily and Italy (Evans 1971, 210-211; Fenech

2007, 39). Typological differences in the shape of the vessels lead to the distinction

between the two phases of Skorba pottery, while similarities in texture and method of

production of both types suggest continuous development (Trump 2002, 30-48). The

sudden appearance of red slip ware points to unbroken contact with Sicily and the

mainland of Italy (Stoddart et al. 1993, 6; Trump 2002, 30). The Skorba periods saw a

consolidation of agricultural dependence, possible evidence for ritual and an increase in

village size, as is shown by the presence of the remains of a wall (Fenech 2007, 39;Stoddart et al. 1993, 6; Trump 2002, 31). The social organisation on the islands can be

described as a largely egalitarian society, with most activity at a household level, while

sometimes different groups would collaborate in a larger project (Stoddart et al. 1993, 6-

7; Trump 2002, 36).

2.1.2 The Temple Period

The Żebbu phase (4100-3700 BCE), preceding the construction of the megalith temples,

displays a break in the continuous development of pottery and the start of a new period

(Evans 1971, 212; Fenech 2007, 39). The shape, fabric and decorations of Żebbu ware

have little in common with the Red Skorba wares, but display a remarkable similarity

with San Cono-Piano Notaro styles, which can be found in Sicily (Stoddart et al. 1993, 6-

7; Trump 2002, 30-49), thereby implying the arrival of new settlers from that region

(Fenech 2007, 40). During the Żebbu phase there was continuous cultural contact with

mainland Italy, Sicily and the smaller islands, and an ongoing exchange of 'exotic' goods,

which brought obsidian from Lipari and ochre from Sicily (Evans 1977, 19; Stoddart et al.

1993, 6-7; Trump 2002, 38-39).

For the next millennium-and-a-half no break in the development of the islands can be

observed. While certain objects were imported from the outside, there was continuous

development of crafts on the islands and an increasing complexity in architecture and

other fields. All in all, the islands did not seem to have been dependent on an influx of

outside material (Evans 1977, 20-21; Trump 2002, 40). Society is thought to have

consisted of extended family groups, whom were often buried together in rock-cut tombs

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 18/134

16

as well as natural caves. These larger family groups would have engaged in competitive

activities, possibly the gaining of prestige/status through exchange (Stoddart et al. 1993,

6-7; Trump 2002, 40-44).

The next period in Maltese prehistory, the Marr phase (3800-3600 BCE), is not well

represented in the archaeological landscape of Malta and only has a few known deposits.

During this phase we see a change in the ceramics, but also a continuation of most of the

established phenomena such as the exchange of obsidian with Lipari (Evans 1971, 215).

The pottery made during this phase can be described as being "on the whole better made,

harder fired, and darker in colour than Żebbu " (Trump 2002, 217). Not much funerary

or domestic architecture from this period has survived and little can be derived from what

is left. Some scholars describe the phase as a transition between the earlier Żebbu and

the succeeding gantija phases (Evans 1971, 215), while others identify the Marr phase

as a new phase based on the discovery of a sterile level during the excavations in Skorba,

distinguishing different periods (Trump 2002, 218).

The pottery of the next period in the chronology of Malta, the gantija phase (3600-

3000 BCE), is characterised by incised decoration of lines, scratched on the surface after

firing (Evans 1971, 215). There is little to suggest a big change in the way people lived

their lives (Trump 2002, 209). Most researchers prefer to see this period as one of

growing insularity and cultural isolation, whereby an increased ritualisation of the

landscape commenced (Stoddart et al. 1993, 7). While trade still continues, there is no

excessive amount of imported objects present in the archaeological material, therefore it

is highly likely that the simple mixed economy maintained the shape it had in

contemporary cultures in the Mediterranean (Trump 2002, 234). There is still little

evidence for the domestic life of the people in this phase of prehistory, but a single hut

and traces of a few more have been uncovered at Skorba (Evans 1971, 218; Trump 2002,

207).

The gantija phase marks not only the next development in the typology of pottery, but

also the physical start of the construction of megalithic buildings, often described as

Temples (Evans 1977, 23) and therefore henceforth referred to as such in this study.

There have been extensive studies looking at the development and the typology of these

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 19/134

17

temples.2 This study will not specifically focus on the megalith structures, it will however

briefly discuss the role of the temples in the religious landscape and their use (Chapter

Four). These temples are an interesting development, as the society that built themdiffered not a lot from the contemporary societies in the Mediterranean, which developed

along different trajectories and did not produce monumental buildings on such a scale.

Evidence from these temples might suggest social stratification in the form of priesthood,

but there is little evidence to support this idea (Trump 2002, 236). There is also not

enough evidence the support an often mentioned theory of chiefdom rivalries (Evans

1977, 23; Renfrew 1973), since there is not enough evidence to support the notion of

chiefdoms at all (which could be recognised through -among other factors- social

differentiation in burial or warfare) (Trump 2002, 234-235). Nevertheless the clusteringof the temples, as well as the similarities between them, suggest some sort of social

competition and emulation, possibly between rivaling families (Evans 1977, 23; Stoddart

et al. 1993, 7; Trump 2002, 236).

The next transitional phase is called the Saflieni phase (3300-3000 BCE), named after the

type site al Saflieni, connecting the gantija and Tarxien phases. Originally thought to

have been a small variation in pottery, separate levels of the phase have been found at

Skorba, Santa Verna and Marr (Evans 1971, 218; Trump 2002, 223). The pottery showsa clear continuation of the decorations used in the gantija phase, with slight differences,

foreshadowing later pottery styles (Evans 1971, 219; Trump 2002, 224-225). There was

also a further import of alabaster and other stone wares. The type site of this phase, al

Saflieni, shows a continuous development of the temples from the beginning of the

Marr/gantija period until the end of the Temple period, indicating a state of

continuous development and alterations (Trump 2002, 237).

The final phase of the Temple Period is the Tarxien period (3150-2400 BCE), named

after the type-site Tarxien. During this phase a continuation of established traditions,

including types of pottery, can be witnessed, as well as the introduction of new types of

pottery (Evans 1971; 219; Trump 2002, 226). However, in contrast to the earlier Saflieni

and gantija phase, a crudeness and uncertainty is noticeable in the decoration of the

Tarxien pottery, which gave rise to suggestions that these decorations were imitating

2 See Trump 2002, 69-203, as well as Driessen 1992.

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 20/134

18

foreign pottery. At the same time, the continuation of established tradition gives more

weight to internal development than foreign influx (Evans 1971, 219). This phase in

prehistory yielded a remarkable amount of diverse pottery, in quantity more than everyother period combined (Trump 2002, 226), which could be the result of the long span this

phase stretches, or it could indicate population growth (Fenech 2007, 42).3 This period

also shows a continuation of the use of existing Temples and the construction of new ones

(Evans 1971, 222; Fenech 2007, 42). During this phase a cycle of rebuilding of the

temples can also be distinguished (Robb 2001, 177). Furthermore, there is some evidence

for the weaving industry, in the form of two conical clay spindle-whorls (Evans 1971,

222), and a continuation of the use of bone, encountered in small quantities in earlier

periods, is visible as well (Evans 1971, 221).

One of the characteristics for this phase is the occurrence of carved objects from

globigerina limestone, such as cups, bowls and 'slingstones', but also for more complex

items such as carved plates, a phenomenon dubbed the 'flowering of plastic art' by Evans

(1971, 223). There is an increase in the representation of the human form, as shown by

figurines, cult figures, local figures and votive offerings (Evans 1971, 223). Most of these

items resemble the style of representation popular in the eastern Mediterranean during

this period. The Tarxien period, like its predecessor the gantija phase, was a long-spanning phase and contacts with other cultures are thus well attested in the material

record. The pottery and architecture shows influence from the west, while the figurines

tend to show more of an influence from the east (Evans 1971, 223).

The main source of food for the society during this phase remains agriculture, as well as

dependence on domestic animals, such as sheep, goat, pig and cattle (Evans 1971, 223).

Elaborate arrangements in the temples, as well as the style of terracotta figurines

originating from Tarxien, which seem to portrait priests, lead scholars to the proposition

that there was an increase in social distinction during the Tarxien period (Evans 1971,

223; Robb 2001, 183). The evidence for a priestly caste, the presence of so-called 'oracle-

rooms', and evidence for a healing cult support this hypothesis. Human remains

originating from the Xemxija tombs, displaying a society living a soft live with the

absence of a lot of physical work, which seems to indicate they were not involved in the

3For an overview of the pottery and its typology for this period see Evans 1971.

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 21/134

19

manual labors of building the temples, and that a different stratum than the Tarxien phase

might be represented here, possibly the gantija phase, for many of the finds were

gantija, and only some were Tarxien (Evans 1971, 223; Trump 2002, 162-165).

Figure 2.2: Overview of the carbon dates from the Maltese archipelago (Fenech 2007, 36, table 3.2).

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 22/134

20

2.1.3 The Bronze Age

After the Tarxien Temple4 phase a second complete break in tradition is witnessed, which

has not yet been adequately explained (Driessen 1992, 39; Evans 1971, 224; Trump 2002,

38). There is much debate about the chronology and even more about the reasons for this

discontinuity. Common theories are that famine, warfare, plague or possibly contact with

new cultures played a role in the cultural break with the earlier phases. Evidence for

warfare for the Early Bronze Age is absent, while the succeeding phases do shown signs

of conflict (Driessen 1992, 39;Fenech 2007, 42; Trump 2002, 239). Taking all of this into

consideration, it seems unlikely that the complete civilisation would have been wiped out

(Trump 2002, 239). Some scholars argue for a break in sequence of about 500 years

(Anati in Driessen 1992, 39; Fenech 2007, 42). This would imply that the people who

represent the following Tarxien Cemetery phase (2400-1500 BCE) had settled on an

empty island. However, one of the carbon dates (T-BM101) suggests an overlap of 400

years between the Tarxien Temple and the Tarxien Cemetery phases (figure 2.2), which

would make both phases contemporaneous. In addition, this would link the Tarxien

Cemetery with the Sicilian Castelluccio culture, with which there are many similarities

(Fenech 2007, 42). Further similarities to the Capo Graziano culture of Lipari are also

attested (Evans 1971, 224; Fenech 2007, 43; Trump 2002, 248). However, the complete

absence of an overlap in material cultures between the two (Tarxien Temple and

Cemetery) phases makes it rather unlikely that the two cultures met. Bonanno argues

against the introduction of new people and rather suggests a break in traditions. His

argument is based on the fact that evidence for the Tarxien Cemetery phase has been

found in the Late Temple Period, when the temples were still in use. Bonanno argues that

the Bronze Age saw a new ritual expression that eliminated the need for monumental

construction (Bonanno et al., 1990, 202-203).

The temples were not left to decay fully during the new phases. While some temples

(Tarxien, Skorba and Haqar Qim) shown signs of destruction by fire (Driessen 1992, 39;

Trump 2002, 238), others show signs of repurposing, either as a house, as it is the case at

Bor in-Nadur (Driessen 1992, 38; Trump 2002, 238), or as cemetery, thus providing the

4 Which is the preceding Tarxien phase. The 'Temple' bit is added to avoid confusion with the succeeding Tarxien

Cemetery phase.

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 23/134

21

phase with its name. At Tarxien parts of the Temples were used as burial grounds for urns

with cremated remains (Fenech 2007, 43; Trump 2002, 247-248). These new influences

brought with them knowledge of metal (Trump 2002, 246), as well as conflict. This isillustrated by the presence of bronze weapons and an increase in fortification (Driessen

1992, 40; Fenech 2007, 43). The Tarxien Cemetery society most likely supported a mixed

economy (Trump 2002, 255) and lived in domestic huts, as well as in the temples on

some occasions (Fenech 2007, 43). Overall this period does not show much evidence for

cult (Trump 2002, 258), but this will be reviewed in Chapter Four. New stone

constructions in the shape of dolmens were erected on the islands in, attributed to this

period, for some of the dolmens are exclusively datable to this phase. (Evans 1971, 224;

Fenech 2007, 43). The function of these dolmens is unclear, but they might have beenused to house cremation burials (Fenech 2007, 43). The dolmens are very similar to the

ones encountered in the Otranto area in south eastern Italy, where similar pottery sherds

have been found (Evans 1971, 224; Fenech 2007, 43; Trump 2002, 250).

The next phase is named after the type site of Bor in-Nadur (1500-700 BCE), and

shows a survival of earlier tradition in pottery, which resembles the Tarxien Cemetery red

slip wares, but is different in colouring, shapes and decoration (Evans 1971, 225). While

pottery survived from this phase, however fragmentary, not much metal has survived(Evans 1971, 226). A new wave of immigrants seems to have introduced this new type of

pottery, which is similar in style to the Thapsos ware from south-east Sicily; these new

settlers might have co-existed with the Tarxien Cemetery people (Evans 1971, 226;

Fenech 2007, 43). The Bor in-Nadur period is characterised by settlements on easily

defendable hilltops, often fortified further with walls when deemed necessary (Evans

1971, 226; Fenech 2007, 44; Trump 2002, 252). In addition, there was settlement in caves

(Fenech 2007, 44; Trump 2002, 253) or in oval huts (Evans 1971, 226). Also known are

quite a few bell-shaped silos cut into the bedrock, which were used for grain and waterstorage (Evans 1971, Fenech 2007, 44), and loom weights and spindle-whorls provide

evidence for weaving (Evans 1971, 226; Trump 2002, 255).

The short Baħrija phase (900-700 BCE), spanning only two hundred years, can be

distinguished by its pottery. Most of the material originates from Barija, the type site.

The pottery resembles earlier ware, however with more complex decoration of foreign

inspiration. In addition, a new type of painted wares was introduced, which seems similar

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 24/134

22

to the Fossa Grave cultures of Calabria (Evans 1971, 227; Fenech 2007, 45). Co-existing

with the Bor in-Nadur culture, the Barija phase seems more of a regional

differentiation than a completely different culture (Evans 1971, 227; Trump 2002, 274).

2.2 Proto-historic phases

The end of the prehistory is marked by the arrival of the Phoenicians on the archipelago

and there is general consensus that this had happened by the end of the seventh century

BCE. Although the Phoenicians (700-550 BCE) were a literate people, they rarely used

their skills to write down history. This apparent lack of ‘historical accountability’ on the

part of the Phoenicians, prompted scholars of Maltese history (notably Trump) to

effectively start the Historic Period of Malta in 218 BCE, after the Roman conquest

(Trump 2002, 295). Whether one agrees with this or not, for reasons of practicality this

study follows Trump and groups the five centuries of Phoenician/Punic presence under

the proto-history of the islands. As we have seen in the previous sections, the prehistory

of the Maltese islands was divided into cultural sequences based on the coherence of their

material culture, mostly pottery. In contrast, the proto-history and historic phases are

distinguished by the prevailing political rule, e.g. Phoenician, Roman and Byzantine

(Fenech 2007, 45). Whereas the periods of political domination allow us to establish

chronological differentiation, the material culture might have spanned across several

periods of political rule.

When the Maltese islands still enjoyed their Bronze Age cultures, the East saw the rise of

a maritime people, often dubbed the Phoenicians. To understand properly the Phoenician

phase on Malta, one must define these new people and look at their motives for crossing

the Mediterranean Sea. The word "Phoenicians" is not the term used by the people

themselves, but rather one used by the Greeks to describe the "Canaanites", as the people

used to call themselves (Ball 2010, 4-5; Bonanno 2005, 14-15). They are also often

referred to as "Sidonians", or in a later period as "Carthaginians" or as being "Punic". All

of these words are labels created to group together the peoples of different city-states, the

foremost being Tyre. This study will use the term "Phoenicians" to refer to the seafaring

people originating from the Levantine littoral (comprising city-states such as Ugarit,

Byblos, Tyre, Sidon and some more), which colonised a large part of the islands and the

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 25/134

23

mainland surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. Several waves of Phoenician expansion can

be recognised5. During their second wave of expansion, in the ninth century BCE, the city

state of Carthage was founded on the North African coast (today’s Tunisia). WhileCarthage grew, Tyre declined, and a shift in power from East to the Southwest occurred.

That is why, from 550 BCE (after the Carthaginian defeat of the Greeks in Sicily)

onwards the term "Punic" will be used to discuss the sphere of influence of Carthage over

the Phoenician colonies (Ball 2010, 19).

2.2.1 Arrival of the Phoenicians

First contacts between the Phoenician people and the Maltese population most likely

occurred much earlier than 700 BCE. Most scholars argue that the actual colonisation

took place during the 8th century in the area of Mdina and Rabat (Bonanno 2011, 40;

Fenech 2007, 45). Sagona pushes the date of Phoenician contact back to 1000-900 BCE,

based on the pottery repertoire of the archipelago (2002, 2), while she confirms the period

of colonisation during the 8th century, calling this period the "Established Phase I: fully

fledged Phoenician colonisation" (Sagona 2008, 500). The island offered an ideal

situation for the seafaring merchants, with its sheltered harbors and its conditions as

"convenient stopovers on their long open-sea voyages between their motherland

Phoenicia in the east and their many colonies in the west" (Bonanno 2011, 38; Trump

2002, 296), a point confirmed by ancient authors such as Diodorus Siculus (Diod. Sic. 5,

12 in Bonanno 2005, 11-12), emphasising the importance of the islands as a shelter and as

a trade post.

The local people were not replaced by the new colonisers and no cultural break can be

witnessed during these phases (Trump 2002, 296). The archaeological material clearly

shows transitional phases of increased cultural contact before the 8th century and even

after the 8th century the remains are never purely Phoenician (Sagona 2008, 488; Trump

2002, 296-297). To sidestep the discussions about ancient territoriality, identity and

politics Sagona uses the word "Melita" to describe the population, local as well as

eventual settlers on the islands, rather than to talk about proper Phoenicians, so as to

indicate the large role the local population still played during these phases (Sagona 2008).

5See Ball 2010 or Moscati 1988 for a more complete overview of the history of the Phoenicians.

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 26/134

24

The Phoenicians would probably have settled first in the Mdina region, where the Bronze

Age population was very present, as well as in prominent harbour areas (Bonanno 2005,

22-23).

It is unclear how exactly the spread of Phoenician culture would have occurred, but it is

clear that this happened quite fast. Whether the Phoenician settlers themselves spread

across the islands, or the local people adopted and spread the customs is hard to discern.

The importance of the Phoenician hegemony on the islands is clear however, as their

influence can be traced throughout Maltese history. The language spoken on the islands

could well be a derivative of the old Phoenician language (Ball 2010, 7), or it might be

the result of Arabian conquest in later times.

Two inscriptions from the Early Phoenician phase have been found, both dedications to

the deity Baal Hammon, effectively the first written sources from the islands, marking the

true end of prehistory (Bonanno 2005, 42-43). One of the most important features from

this early phase is the re-introduction of rock-cut chamber tombs, used previously during

the Temple period (Bonanno 2005, 46-49; Malone et al. 2009, 98-99; Trump 2002, 296).

Most of these tombs, datable to the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, are located in the

Mdina-Rabat surroundings, suggesting that this area was the main urban settlement

(Bonanno 2005, 46-47). There is also evidence for the re-purposing of Temple buildings

in some areas for Phoenician deities (the most well-known example being Tas-Sil).

Furthermore, the material culture shows a tendency for contact with the East, rather than

the West, as is indicated by similarities in statuary, architecture and Aegyptiaca (Bonanno

2005, 49-50; Trump 2002, 296; Van Sister 2012).

2.2.2 Influence from the West

The succeeding Punic phase is in many ways a direct continuation of the Phoenicianphase. During this phase the Mediterranean was host to a number of commercial, political

and military hostilities between the different growing powers. Among the important

players during the Punic phase (550-218 BCE) are the Carthaginians, the Etruscans, the

Greeks and near the end of the phase (eventually giving rise to the next phase of Maltese

history) the Romans. Wars between the Greek city-states and the Carthaginians shaped

the area around Sicily (Bonanno 2005, 74-75), which was conquered by Carthage in 550

BCE (Ball 2010, 29). In 524 BCE the Phoenician homeland was incorporated into the

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 27/134

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 28/134

26

80). In addition, we find inscribed pottery with dedications to the goddess Ashtart

(Bonanno 2005, 83). Until the advent of the Roman period, no local coins have been

minted on the islands (Bonanno 2005, 86). Coinage had been in use from the sixthcentury BCE onwards, as is shown by the presence of fifth century BCE Greek coinage,

originating most likely from Greek Sicily, as well as fourth century BCE Punic coins

from Punic Sicily (Bonanno 201, 48).

While there is not much evidence for definitive settlements, it is thought that there were

at least two settlements present on the islands during this period (Bonanno 2005, 86).

This assumption is based on the clustering of rock-cut tombs. If this is to be taken as an

indication for settlements, than one could argue that another settlement might have been

located near Marsa, one of the favored harbor locations (Fenech 2007, 45). There is

ample evidence for a settlement near Mdina-Rabat, where Phoenician remains appear to

have been replaced and are cut into by Punic remains, in the form of an ashlar wall

(Bonanno 2005, 97; Fenech 2007, 46). There seems to have been separated domestic

quarters near Rabat, possibly indicating a shift in purpose from the main area of Mdina as

a city-center (Bonanno 2005, 87; Fenech 2007, 46). Bonanno also argues that the so-

called "round towers", often interpreted as Roman, are in fact from this period. Apart

from various religious buildings, which will be discussed later on, scholars argue for aspread of country houses during this period. While there is no conclusive evidence for

this, most later Roman villas have earlier foundations and are often accompanied by

Punic Pottery (Fenech 2007, 46).

During the Punic phase on the islands there is an increase in the use of rock-cut tombs,

changing only slightly in its floor plans (Bonanno 2005, 92-93; Fenech 2007, 45). Most

of the material culture surviving from this period originates from these tombs. As there

are more tombs than in earlier periods, there is also more archaeological material culture,

although limited to one specific category of finds (grave goods, rather than domestic

material). While the tombs are not poor, they lack some types of objects which are

common in Punic tombs in other regions, such as banded glass, ivory and faience

(Bonanno 2005, 94). A continuation of the import of Aegyptiaca and Greek precious

objects can be witnessed from the tombs (Bonanno 2011, 43-44). Most abundant in the

material culture is the pottery, which was extensively studied and classified by Claudia

Sagona (2005).

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 29/134

27

2.3 Roman Period

2.3.1 Roman Conquest; Malta under the Republic

As mentioned above, the islands were incorporated into the Roman sphere of dominance

in 218 BCE, when Tiberius Sempronius Longus conquered the islands with little

resistance (Bonanno 2005, 132). The islands were included in the province of Sicily,

which was under a propraetor chosen by Rome. During this time the islands were still

allowed to mint their own coins and they seem to have been quite autonomous during the

early Roman period (Bonanno 2005, 133). Most information for this period of early

Roman occupation is gained from literary sources. Titus Livius discusses the conquest of

the islands in his books covering the Punic Wars (Livy, 21, 51, 1-2 in Bonanno 2005,

143) and Marcus Tullius Cicero accuses Caius Verres of many wrongdoings and crimes

committed when he was governor of Sicily for three years (Cic., Verr., 2, in Bonanno

2005, 145-148). Cicero’s allegations against Verres give us an opportunity to learn more

about the social-political climate in the civitates. Malta is also discussed by Strabo

(Strabo, Geog., 6 and 17, in Bonanno 2005, 149) and the contemporary situation of the

islands to the author has been delivered to us by Diodorus Siculus (Diod. Sic. 5, 12 in

Bonanno 2005, 149). Sicily, along with Lipari and Malta, was divided into multiplecivitates with different rules regarding each community. Their main function was to

provide Rome with a manageable administrative unit, mainly to collect taxes (Bonanno

2005, 140-141). The local administration however was left largely in the hands of the

locals, leading to large differences in different civitates under Roman rule. Malta thus

remained largely under the influence of the earlier (and concurrent) Punic hegemony, but

was also affected by Hellenistic influences, as well as dependent on interaction between

Sicily and the Maltese archipelago.

These cultural interactions are reflected in the material culture. Much of the Hellenising

movement can be recognised in statuary (Bonanno 2005, 163) and in other aspects of the

material culture, such as mosaics. Despite these influences there is much survival of

Punic traditions present on the islands, most of them religious (Fenech 2007, 46). While

the iconography of female deities seemed to Hellenise more and the deities were

associated with Graeco-Roman counterparts, the male deities remained in their original

forms (Bonanno 2005, 188-189). This is no strange phenomenon, considering the

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 30/134

28

Romans tolerable stand on foreign religions and the relative autonomy of the civitates.

The same goes for language, the Punic language might have survived even up to the fifth

or sixth century AD (Fenech 2007, 46). Within the numismatics of the islands a clearevolution can be distinguished during the early period of Roman occupation, where the

coins first display Egyptian and Levantine iconography with Punic legends, which slowly

get replaced by Greek ones, maintaining the Punic iconography (Bonanno 2005, 157).

Near the end of the Republican period Latin gets introduced into the legend.

Many sites and locations of settlement from the preceding phase continued to be used.

Most of the aforementioned country houses originate from this period and the

concentrated urban centers present during the Punic phase continue to grow, a

development clearly visible in the corpus of pottery (Fenech 2007, 47). The cluster of

activity found at Mdina-Rabat is now identified as the Roman city Melita (Fenech 2007,

47). There is also evidence for the continuous use of several sanctuary sites, such as Tas-

Sil. Further continuation of earlier customs can be witnessed in the mortuary customs.

Inhumation, cremation and the use of specific burial urns, set into underground rock-cut

tombs remain the main method of burial (Bonanno 2005, 162-163; Fenech 2007, 47).

These tombs adopted a rectangular shaft and chamber and became more clustered in the

form of hypogea, which can mostly be found in the Mdina-Rabat area near the countryhouses or among the coast (Bonanno 2005, 163; Fenech 2007, 47).

The continuation of these former traditions, both religious and in material culture, lead

some scholars to consider this phase as an extension of the Punic period (Sagona 2000,

84; Said-Zammit 1997, 5), or as Romano-Punic (Bonanno 2005, 190). There are a

number of objects datable to this phase that are often classified as "Roman" (difficult this

terminology might be, considering the Hellenising nature of art during this phase), such

as statuary, but also pottery, among which the famous terra sigillata and normal "Roman"

pottery (Bonanno 2005, 168-170).

2.3.2 Imperial Malta

The Roman period was not by large homogenous, but showed fluctuations in activity and

political situations. On Malta the peak in activity would have been between the second

century BCE and the early third century CE, after which a decrease in activity occurred,

which would not recover until the end of the Roman period (Fenech 2007, 47). In 27 BCE

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 31/134

29

the political situation in Rome changed when Octavian emerged victoriously from the

civil wars and became the first emperor of the Roman Empire. During this civil war

Malta and Gozo lost many of their autonomous rights, possibly because they chose thewrong side (Bonanno 2005, 195). In the subsequent division of provinces between the

emperor and the senate, Sicily became a senatorial province, governed by a proconsul,

and often assisted by not only quaestors and legates, but also by an emissary from the

emperor, a procurator (Bonanno 2005, 195-196). The political status of Malta is unclear

during the first part of the period, possibly a setback from the infraction mentioned above.

During the second century CE however there is epigraphic evidence for Malta having a

municipal status (Bonanno 2005, 232). Social differentiation was a standard during the

Roman period and although its exact amount of strata is unknown, it is often expressed inthe holding of religious priesthood (Bonanno 2005, 234).

Confirmation of the names of the urban areas is given by the geographer Ptolemy (100-

178 CE), who mentions the cities of Melita and Gaulos, as well as two sanctuaries (one

for Juno and one for Hercules) and a landmark called Chersonnesos (Bonanno 2005, 200-

202). Their exact location is hard to determine, although many scholars have published on

the whereabouts of the sanctuaries (such as Vella 2002). It is from this period that we

have inscriptions in Latin, among which not only dedications, but also onecommemorating the good deeds in reconstructing a temple by one of Augustus'

proconsuls (Bonanno 2005, 203-204). Most of the Roman architectural material remains

from the islands are datable to this period. While the necropoleis continue to be used and

grow, there is also a lot of evidence for the opening and re-use of already existing tombs

(Bonanno 2005, 218). Isolated rock-cut tombs became less used during the second

century CE, possibly indicating a shift in burial rites (Bonanno 2005, 218). Coinage was

now minted not locally, but in other parts of the Roman Empire, such as Sicily (Bonanno

2005, 227).

During the pax Romana Malta benefited greatly from her geographic position in the

Mediterranean and prospered, as is displayed in the restoration of buildings, as well as the

import of luxury goods from far away (Bonanno 2005, 238). The presence and

distribution of so many rustic villas suggest an intensive cultivation of olives and grapes

(Bonanno 2005, 240-252). The textile industry is attested for by the presence of loom

weights and spindle whorls (Bonanno 2005, 241). During the early Principate the

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 32/134

30

archipelago appears to accepted the Roman influence and Latin became the official

language, while Punic remained the spoken language of the commoners (Bonanno 2005,

253).

2.3.3 Late Antiquity

During the third century CE there was a general crisis in the Roman Empire. Emperor

Diocletian (284-305 CE) took measures, among which was the introduction of the

tetra rchy (the rule of four emperors), effectively dividing the empire into two parts, each

governed by a co-emperor and a lieutenant. One of those Augusti, co-emperors, went as

far as to move his seat of power to Byzantium, giving rise to the Byzantine empire. While

the Eastern Byzantine Empire grew and prospered, the Western Empire declined

evermore, until the deposition of Romulus Augustulus, last emperor of the west, in 476

CE. Malta was incorporated into the Byzantine Empire in 535 CE, during the time of

expansion under the Emperor Justinian I (Bonanno 2005, 258; Fenech 2007, 48). Three

hundred years later it was won over by the Muslim Arabs in 870 CE (Bonanno 2005,

258).

Figure 2.4: Overview of the chronology of the Maltese archipelago as set by different authors (Fenech 2007,

35, figure 3.1).

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 33/134

31

The periods between the third century CE and Malta’s incorporation into the Byzantine

Empire are hardly represented in the archaeological records and therefore leave more

questions than answers. Around 445 CE Malta is thought to have been occupied by theVandals and around 477 CE possibly by the Ostrogoths (Bonanno 2005, 258; Fenech

2007, 48). Most of the evidence from these phases is of religious nature, in the form of

the basilica of Tas-Sil and the shrine attached to a rock -cut tomb of L-Abbatija tad-Dejr

in Rabat (Bonanno 2005, 259). There are a few inscriptions from the early fourth century

CE on Gozo, which imply that Gozo by this point had an autonomous government

(Bonanno 2005, 160-161). It is during this period that Christianity most likely developed

on the islands, visible mostly in the burial rites, while there is also evidence for a Jewish

community. For a complete overview of the chronology of the islands, as set by differentauthors, see figure 2.4.

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 34/134

32

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 35/134

33

3. Theoretical discussion

This chapter will explore some of the theoretical problems related to the study of

religious developments in the past. Several of these problems cannot be solved perfectly,

and compromises need to be made, while others can be solved by providing good

definitions and setting boundaries. This is necessary to address at the start of the study,

so as to be aware of theoretical problems and to be able to avoid them. This study

concerns the religious developments in an insular context and is thus prone to several of

these problems. The chapter opens with a brief critical review of the established

chronology and addresses the problems arising from compartmentalising the past. The

second part of this chapter will be dedicated to the array of problems related to the study

of past religion. Definitions of related terminology will be provided, which will be

followed during the rest of the study. The last part of the chapter will focus on the unit of

analysis and on the problems that arise when drawing parallels between different

geographic regions. Mediterraneanism, as a theoretical discourse, will briefly be

discussed, for phenomena (especially religious phenomena) are often drawn in a broader

context than they should, and this comparative approach could well lead to assumptions

one does not want.

3.1 Critical review of Malta’s historical chronology

There are many issues that arise when studying the prehistory and history of the Maltese

archipelago, some of them practical, while others are on a more theoretical level. For

instance, there are not many carbon dates available for the entirety of prehistory (see

figure 2.2) and these dates already show quite some discrepancies in itself. The current

chronology is therefore based mostly on the typology of ceramics, supplemented by the

carbon dates. One can even go as far as to say that most archaeologists try to fit the

carbon dates into what the typology dictates, which in itself is a faulty way of studying

the past. The units into which the prehistory has been compartmentalised are mostly

based on the cohesion of the pottery wares, which in its turn might show colonisation

waves or other waves of interaction, but is not a definitive indication thereof. In case of a

continuous development, as can be witnessed for some periods, such as the Grey and Red

Skorba, where does one draw the line between periods and why does one draw this line?

There is no simple answer to this theoretical problem, but for now it is sufficient to say

that to adequately discuss changes in past human behavior, an artificial distinction is

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 36/134

34

necessary to properly contextualise these changes. The same is true for regional

distinctions, such as the Barija, and for the afore-mentioned 'transitional' phases, such

as the Saflieni phase. For the sake of discussion, these phases will be distinguished asdiscussed in Chapter Two.

The proto-history and the history of the Maltese archipelago have been set-up in phases

based upon the political domination. This is in contrast to prehistory, which is set-up

based upon changes in material culture. The problem with the socio-political distinction is

that this is often not directly reflected in the material culture. It might take years for the

influence to be shown in the overall material culture. One can discuss then what is the

better way of dividing the past. Attempts have been made to synthesise a chronology

which fits both systems, socio-political as well as material-based (e.g. the Romano-Punic

phases recognised by Claudia Sagona), but this often leads to more complications. One

needs to remember that most of the terminology we apply to the past are only labels

which we constructed and make use of. As long as we are aware of this, as well as the

fact that even in a socio-political division the material culture does not directly follow this

division, it should not raise that many problems.

3.2 Reconstructing religion

The reconstruction of past religious and ritual activities is not an easy feat and it is always

subjected to different opinions and criticism. The historiography of religious studies is a

vast subject in its own right and therefore will not be treated within this study. Religion is

one of the aspects of human life that is present in almost every instance from the Upper

Paleolithic onwards (Insoll 2004, 5) and has huge consequences for the development of

cultures, as well as for our interpretation thereof. Considering the subject of this thesis,

the development of religion throughout the ages on the Maltese archipelago, it is

necessary to briefly look at the definitions related to the study of ancient religion and tobriefly mention often made mistakes related to this, so as to avoid them and to identify

correctly religious activities on the islands and discuss them adequately within their

cultural and historical context.

3.2.1 Discussing and recognising religion

There is no conclusive definition of religion that suits all situations and fits every model

and for which there is unanimous agreement. The lack of clear definitions is also true for

8/12/2019 Cult Continuity a Religious Biography of the Maltese Archipelago From the Neolithic Up Till 535 CE-Libre

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/cult-continuity-a-religious-biography-of-the-maltese-archipelago-from-the-neolithic 37/134

35

other concepts related to the study of religion, such as ritual, sanctuary, temple and shrine,

but also to broader concepts such as culture and civilisation. Nevertheless most of these

concepts have been used to describe phenomena and activities in the past, so as to makethese phenomena more tangible and to be able to discuss them. While religion in itself

can be considered to be intangible, thus creating a paradox when made tangible, it is

indeed necessary to make use of some labels, for without them discussing these

phenomena would become impossible. But in its core, religion remains indefinable, and it

can be seen as a created discursive formation, which includes the irrational, the

indefinable and the intangible (Insoll 2004, 6-7).

Many problems arise when separating the secular and the spiritual worlds, creating an

artificial dichotomy, and viewing these parts from a contemporary point of view, while in

the past this division was not even present. Contemporary ideologies played (and still

play) a large role in study of the past, as can be witnessed when reviewing the way past

scholars discussed religion. It is not within the scope of this research to discuss all of

these discourses, but suffice it to say that while not one of them offers a complete view of

reconstructing past life, most of them offer valuable partial views. The reductionist view

offered by evolutionary paradigms, such as those by Tyler and Frazer (Pals 2006), the

distinction between sacred and profane, as offered by Durkheim (Durkheim 1912), as

well as the phenomenological viewpoints offered by Eliade (Eliade 1956) and later post-

processual archaeologists each add value to the broader understanding of past religion.

Processual archaeology placed religion in a larger system, but did so at the cost of the

individual. One has to step beyond established biases within the archaeology of religion

(of which there are many) and break established dichotomies when creating a working

definition of these concepts. These concepts again are necessary to not fall into the post-

modern trap of deconstructing everything and saying that we know nothing at all.

After defining religion and its related concepts, there is still the problem of properlyrecognising it in the material record. It is in this area that there are many biases within the

field of archaeology, placing the focus on ritual and funerary archaeology. As a result of

the compartmentalisation of the processual archaeologist, as well as for practical reasons