cue-wp-004

-

Upload

ar-apurva-sharma -

Category

Documents

-

view

9 -

download

1

description

Transcript of cue-wp-004

Working Paper 4

Land reservations for the urban poor: the case of town planning schemes in Ahmedabad

Rutul Joshi Prashant Sanga

December 2009

Centre for Urban Equity

(An NRC for Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, Government of India) CEPT University

Kasturbhai Lalbhai Campus, University Road, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad – 380009

Land reservations for the urban poor: The case of town planning schemes in Ahmedabad

Rutul Joshi1

Prashant Sanga2

The Urban Housing Challenge

Time and again, it has been pointed out that an essential dimension of urban development is addressing the need for secured shelter for the low income groups in the cities, in particular of the slum dwellers. Slums represent poor living quality and also indicate urban distress. At the same time, these also indicate a housing solution as well as investments by the poor in urban housing stock.

Scarcity of developed and serviced land, high land prices, rising prices of materials and resource constraints of government agencies are some of the factors which forces the urban poor to live in a substandard housing and unhealthy environment. Land in urban area, on one hand, is a scare resource which needs to be utilized appropriately in order to achieve balanced development and on the other hand, there is a very big need to supply land for housing the poor.

The total housing shortage in India was about 24.71 million dwelling units in the year 2007. Amongst this 21.78 million dwelling units comprised were required for SEWS (social and economically weaker section) housing while 2.89 million dwelling units for LIGs. National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) 2002 survey indicate that 52,000 slums hold eight million urban households, representing 14 per cent of the total urban population in the country. This explains the failure of provision of adequate housing stock with minimum basic services for the urban poor resulting in rapid growth among the slum population in the cities. Low affordability of the poor poses a very important challenge in ‘Housing for All’ goal of the national housing policy of 2007. Such conditions create an ever mounting ‘house-less’ and ‘land-less’ population in the cities which takes shelter in slums and squatter settlement.

1 Faculty of Planning and Public Policy & CUE (Centre for Urban Equity), CEPT University,

[email protected] 2 This work is partially based on the field investigations carried out by Prashant Sanga for his masters’ level

dissertation. [email protected]

As per Ministry of housing and urban poverty alleviation, (Socially and Economically Weaker Section) SEWS households and (Low Income Group) LIG households are defined as the families having monthly household income of less than Rs. 3,300 and Rs. 7,300 respectively. However, this has been the subject to revision by the Steering Committee of the scheme of affordable housing from time to time. The total number of households coming under the category of ‘SEWS’ in the city of Ahmedabad were 105,472 as on Nov 2005.

One of the biggest hindrances to implement developmental project related to the urban poor is the availability of land and number of government agencies have, time and again, argued so. In order to make land available to the government, various planning systems of the country have practices of reserving land for public purposes out of the total land pool.

Land Development Mechanism – Town Planning Schemes in Gujarat

In Gujarat and Maharashtra, land pooling mechanism is adopted for urban land development. Under this, Town Planning (TP) Schemes are prepared in which land is not acquired by the government agency. It is reshaped, readjusted and returned to the original owner. Generally when a TP SCHEME is laid in an area, about 40 per cent of land is utilised in providing common infrastructure and facilities like roads, gardens, play grounds etc. This proportion of land area is deducted from each of the individual land owners’ original land. Land parcels retained by the planning authority are then used for ‘public purposes’. Evidently, the land area of a land owner decreases but overall value of the land increases several times because with the implementation of the town planning schemes, the land parcels become more organised and accessible with better infrastructure provision.

In Maharashtra, the TP Schemes are prepared and implemented under Maharashtra Regional and Town Planning Act, 1966; and in Gujarat, Gujarat Town Planning and Urban Development Act (GTPUD), 1976. Major difference between land pooling mechanism (TP Scheme) and land acquisition mechanism is that under the land pooling, the benefit of urban development is realized by the original owner of the land, whereas in the acquisition model, the planning agency benefits and not the original owner.

At the local area level, the potential of any plot improves with regularity of shape, improved accessibility, availability of facilities in the neighbourhood and better linkage with other parts of the city and TP Schemes facilitates these changes. The improved potential obviously results in increment of market value. Since this increase takes place without any effort on the part of the owner, it forms ‘Unearned Increment’ which can be shared by the owner and the government agency. The owner receives compensation for the land deducted from his original plot. The

owner also retains at least half of the increment in market value of the plot immediately available and full increment in the future.

The TP Scheme as a detailed local area planning mechanism has been practiced in Gujarat for more than last eight decades. In Ahmedabad, the first TP Scheme was prepared in Jamalpur in 1917. Area for a TP scheme is taken as 250 acres to 300 acres (100 or more hectares) as a thumb rule. It was prepared under the provisions laid by Bombay Town Planning Act, 1915. Now the GTPUD Act, 1976 provides for the planning and administration of TP Schemes in the state.

Research design and limitations

This paper examines the role and effectiveness of the much talked about town planning schemes of Ahmedabad in providing land for the poor households. First of all, the list of reserved land in Ahmedabad was acquired from the Municipal Corporation. Based on the list, the reserved land for the SEWS (socially and economically weaker section) housing were sorted out, located and mapped. Finally, 172 plots were allocated for SEWS housing which amounts to total area of 135 hectare. All the 172 plots were visited and the detailed land inventory comprising of the size of the plot, proposed and current use, access to road and basic services was prepared and analysed.

However, when the field investigations carried out in January 2009, the readily available list was comprised of the reserved land parcels located in the pre-2006 municipal limits of Ahmedabad3. In the adjoining areas to the municipal limits were being planned and administered by the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA) till 2006. And thus, this work is limited to the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation’s jurisdiction till 2006 and it takes in account the town planning schemes planned and implemented between 1976-2006.

Town Planning Schemes in Ahmedabad

The TP Schemes in Ahmedabad city are a well-known tool for land management which provides serviced land parcel for urban development efficiently. In order to provide affordable housing to the poor population of a city, the GTPUD Act (1976) has a provision of reserving land for the urban poor defined as socially and economically weaker section housing. The idea of reserving land for the SEWS housing is to minimize the distance between residential location of the poor and the distance from the work area by providing land for the poor in all the TP Schemes in a city.

3 The limits of Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation were expanded from 256 sq kms to 464.16 sq kms in 2006 and

subsequently.

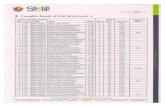

Chart 1: Public Purpose Land within AMC Limits 2006

As per the GTPUD Act (1976), of the 40-50 per cent of remaining land for public purpose, 15 per cent of land is reserved for roads, 5 per cent for open spaces (play ground, garden, parks), 5 per cent for social infrastructure (schools, dispensaries, fire station, public utility etc.) and there are also norms for up to 10 per cent reservations for SEWS housing. To be precise, section 40(j) of GTPUD Act provides for “the reservation of land to the extent of ten per cent; or such percentage as near there to as possible of the total area covered under the scheme, for the purpose of providing housing accommodation to the members of S.E.W.S.” The ownership of the common plot/land reserved for public purposes rests with the

government or local authority. The map above shows the locations of the ‘public purpose’ reserved land in the pre-2006 expansion of municipal limits in Ahmedabad city.

Based on the secondary information collected from the town planning department, Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation in 2009, it has been observed that 1692 hectares of land has been kept reserved for public purposes by the local authority. Out of 1692 hectare of land, 172 plots

are allocated for SEWS housing which amounts to total area of 135 hectare (Chart 1).

Map 1: Distribution of all the reserved lands in Ahmedabad

Chart 1 show that maximum land is allocated for the miscellaneous use, which includes parking, small markets, pumping station, fire station, government buildings and recreational purpose. The land for miscellaneous use accounts for 623 hectares or 36.8 per cent of the total reserved lands for public purpose. This is followed by saleable land for commercial purposes and its accounts for 20.7 per cent of the total public purpose land. The purpose of the saleable lands is to earn profit in order to recover the cost of those lands which are used for social purpose. The allocation of the public lands for slum up gradation and social sectors (schools and dispensary) is small, around 8 per cent (142 hectares) and 6 per cent (162 hectares) respectively. In contrast, the lands reserved for open space and garden accounts 16 per cent of the total or 282 hectares. This indicates that SEWS housing and social amenities do not form the priority of DP reservations.

Land Reservations for SEWS in TP Schemes (1976-2006)

As per the records of the town planning department of the AMC, 172 plots have been allocated for SEWS housing. In the AMC limits by the year 2006, there are about 50 TP Schemes had land parcels allocated for SEWS housing. Out of 986 hectare of land which is reserved for public purpose in these 50 TPS, 135 hectare (i.e. 13.7 per cent) of land is allocated for the SEWS. Most of these lands fall in the southern, eastern and northern zones of the Ahmedabad city. Map 2 shows this spatial distribution of plots allocated for the SEWS.

The concentration of SEWS plots in the southern and eastern Ahmedabad is a mainly because of the majority of urban poor in Map 2: Spatial distribution of SEWS reserved land parcels

Ahmedabad residing in these zones. They are working in the adjoining industrial estates and commercial units or are self-employed in the informal sector. Besides, the land prices in the eastern and particularly southern-eastern Ahmedabad area comparatively lower than the western parts of the city and thus, are easier and obvious practice amongst the town planners to allocate for economically weaker section housing. Within the southern zone, maximum number of SEWS plots are located in the Vatva TP Scheme, where 21 plots have been assigned for the SEWS housing. In the southern zone, 98.8 hectares of land are allocated for SEWS housing out of total 805.7 hectares within the zone.

Current status of SEWS land reservations

It was important to see the usage of the reserved land to determine the status of a mechanism which was devised for the welfare of the poor. It becomes crucial to examine the land reservation mechanisms of the past when the JnNURM (Jawaharlal Nehru Urban Renewal Mission) – the biggest urban development mission of the Government of India since Independence – proposes a certain amount of reservations of land for the poor in cities of India as a mandatory reform of the mission.

There are total 172 plots reserved for SEWS housing amounting to be 135.85 ha within the AMC area (prior to 2006) under various town planning schemes planned and implemented between 1976 and 2006. All the 172 plots were visited and mapped across the municipal zones. A detailed land inventory comprising of proposed and current use, size of the plot, access to roads and basic services was prepared.

It was clear from the land inventory that out of 135.85 ha, about 37.43 ha (27.55 per cent) land parcels were vacant and about 27.2 has (20 per cent) were still under agricultural use (Table 1). SEWS public housing was built merely on 6.11 per cent of land and rest of the land had residential and commercial developments. It is not known whether the surveyed residential and commercial uses on these plots were the legitimate use of not. There are strict restrictions on converting the reserved land in the town planning schemes to the uses other than what is proposed. It is administratively very difficult to convert the reserved land. So there is a strong possibility that the land uses seen on the SEWS reserved land are not legitimate uses.

Most of the allocated residential areas in Danilimada, Narol, Shahwadi and Isanpur south have been illegally occupied, total such area amounting to about 49.94 hectares of the land (out of 135 hectares). In some areas, the SEWS reserved land was being used for the parking of trucks and heavy vehicles. In case of Narol and Shahwadi, plots with FP (final plot) number 2, 4 and 5 are being used for parking on account of their proximity to the National Highway No. 8. Besides, 20 per cent of land currently reserved for SEWS is being used for the agricultural purpose.

Table 1:

Out of thhousing wall the lanbuild’. Mnot be finat the TP42 draft verified t34 hectar

4 In the TPin Septemb

Land useVacant lAgricultuEWS PubOther resOther comOthers Total

Total Rese

he 172 plotwhich is onlnd parcels lo

Much of this lnalised and

P Schemes oTP Scheme

that the ownres of SEWS

P Scheme at Odber 2009.

e land ural Land blic Housingsidential mmercial

rved Lands

Chart 2: Su

ts being alloly 6.1 per ceocated on thland might bsanctioned o

of eastern Ahes and only

nership of theS housing lan

dhav with final

g

s Available,

urvey of Use

ocated for tent of land o

he map 2, thebe entangledor some of thhmedabad wy 10 TP Sce reserved land parcels a

l plot number 3

Ahmedaba

e of Land R

the SEWS oout of the toe AMC mighd in the plannhe land mig

which have rechemes haveands for SEWare vacant. T

38 and 86, con

Area in ha37.43 27.20 8.30 41.33 17.23 4.36 135.85

ad

Reserved for

only 10 plototal 135.85 hht not have aning processht be under eservations e been finalWS housing

This is possib

nstructions for t

a

r SEWS

ts are beinghectare of lanall the land ps where the Tlegal disputfor SEWS hlised complis with the A

bly because m

the SEWS hou

Area in 27.55 20.02 6.11 30.42 12.68 3.21 100.00

g used as Snd4. Out of pockets ‘reaTP Scheme mtes. Lookinghousing, theretely. Our sAMC. Moremost of the

using had just s

per cent

EWS these

ady to might g only re are study

e than lands

started

are located on those TP Schemes which are still to be sanctioned and they are in either preliminary or draft stage.

In any case, the AMC had about 68.99 ha of land (vacant+agricultural+others) where there is a scope to use the land as SEWS housing. Table 5 shows that on the given land (68.99) ha, it is possible to build more than 27,000 housing units following the existing FSI norms (1.8) and following the current norms of construction for the EWS housing (25 sq mts per unit). With an increased FSI of 2, more than 30,000 housing units could be built.

Table 2: Housing Supply Possibility on Reserved Lands

Under utilization of SEWS housing land

The formal planning tool such as the TP Scheme does provide lands for the poor. But the local government does not take the advantage of this and do not built SEWS housing on it due to various administrative and legal reasons. The underutilization of SEWS housing land reflect serious mis-management of resources and inefficient land management. There are land reserved to build housing for the poor very much within the city limits and it is not being used effectively to increase the housing stock for the poor. This study also contradicts the claim that there are no lands available for housing the poor in the city of Ahmedabad and this might be true for the other cities in the state as well.

Such lands could be squatted upon and may be used by the ‘SEWS’ for their own housing subverting the official planning practices. However, this kind of housing is not legal. As per the GTPUD act if the lands reserved for the SEWS are squatted upon then, the local government will have to remove the poor from the land and they could only be housed (on the same land or on some other land) after government builds housing on the land and give it back to the poor (same inhabitants or some other). If there is a demand to legalise the squatter settlement on the SEWS reserved land then the Town Planning Department has to first de-reserve that piece of land, then the state government will have to grant patta (land title) to the occupants of the same land. It is a

Available Land (Ha) 68.99 68.99 FSI (as per DCR) 1.80 2.00 Available Built up 124.18 137.98 In Sq Mts 1,241,820.00 1,379,800.00 SEWS Unit size 25.00 25.00 Number of Units 49,673.00 55,192.00 SEWS Unit size 30.00 30.00 Number of Units 41,394.00 45,993.00 SEWS Unit size 45.00 45.00 Number of Units 27,596.00 30,662.00

long and tedious process, indicating lack of will on the part of the local government to grant lands to the urban poor.

Besides, the municipal budget (from 2002 to 2007) shows that although funds are allocated for urban poor in the municipal budget in the past few years but the actual utilization is very negligible. In the year 2000-01 the fund allocation and actual utilization is 57 per cent which is negligible in the year 2003-04. In the consequent year allocation of money is only 12 per cent but in recent time it has increase. Only in the current years (2006 onwards) with the introduction of the BSUP component of JnNURM the fund utilisation for SEWS housing in the municipal budgets have increased. This means that there were provision of land and finances both available with the urban local body which are not utilized to provide housing to the poor.

What kind of plots are allotted for SEWS housing?

There are also concerns regarding the type of land is allocated for the SEWS reservation. It is observed that the land pockets which are reserved as SEWS housing are often does not get enough attention from the planners. They might have odd shapes or they are on difficult terrain or low lying area. Most of the plots reserved for urban poor are located at distant places which are not easily accessible which directly affects the quality of the housing scheme.

For example, In the TP Scheme of Hanspura Muthia (Map 3), the land parcels allocated for SEWS housing have irregular shapes and it is difficult to conceive housing schemes on such

Map 3: Hanspura Muthia TP Scheme Map 4: Hathijan-3 TP Scheme

Plots reserved for SEWS housing

plots. Similarly, in case of Haithjian -3 TP Scheme (Map 4), the shape and size of the reservation land for the urban poor is irregular, small and it is located in the low-lying area. In case of Vatva –VI, with TP Scheme No-80, the land allocated for the urban poor is not easily accessible to the main connecting roads. Vatva –VI TP Scheme is currently in draft stage (January 2009) and in the draft plan there is no connectivity given to the SEWS plots directly.

In essence, reserving lands for the socially and economically weaker section housing are deficiently planned; inadequately financed and inefficiently implemented. Only reason why this mechanism survives and is practiced because of it is legally binding under the GTPUD Act. It is an example of a mechanism which is mainly devised for the poor which does not work for them. However, if this mechanism can be used effectively to provide land for the urban poor’s housing, it can be the most useful mechanism.

Emerging Issues – Land reservations and the poor

a. TP Scheme doesn’t work for the public domain and for the poor Our research in case of Ahmedabad clearly demonstrates that even the TP Scheme mechanism, one of the most celebrated planning mechanism, does not really work for the benefit of the poor, given the former apathy and now hostility to the urban poor in our cities. It is a classic example of top-down planning mechanism which is well-intentioned in providing land for the poor but it fails in its execution completely.

It has been a long-standing critique of the TP Schemes in Gujarat that although it efficiently returns streamlined land parcels back to the private land owners, on the public domain front efficient and equitable use of land resources depends entirely on the inclination, interests and initiatives taken by individual technocrats involved. Thus, although lands are reserved for the EWS housing they do not get used for the purpose and lie unutilized and therefore prone to encroachments. No one is called to account if the reserved lands are not used for the purpose.

Today, the AMC is not even considering to use the SEWS reserved plots for BSUP housing under JnNURM as most of these land parcels are stuck in the sanctioning process. It is ironical that there are other municipal corporations in the country struggling to find land parcels to implement schemes for the poor and here there is a mechanism of making land available to the poor but it is not being utilised properly.

b. TP Scheme need to be tighten for faster delivery of serviced land The TP Scheme mechanism too is very slow in spite of its advantages of being more pragmatic as well as democratic as far as the land owners are concerned and in comparison to land acquisition mechanism. It needs to be further tightened up to deliver land parcels for the poor on

a regular basis. In case of the SEWS reservations, the land should be transferred to the ULB at the stage of draft scheme itself where the ULB may propose a housing project in the given time frame. Secondly, there should be an independent audit of the quality of land parcels marked in the TP Scheme and the quality housing projects build on them subsequently. But, a TP Scheme mechanism, which sounds more pro-people and also pro-poor may fail to deliver in a system where the bureaucracy rules the roost.

c. What should be the model of public housing on the SEWS reserved land? There may not be one answer to this question. It is also not expected of the ULB to build public housing themselves on all the SEWS reserved plots. The ULBs can enter into a partnership with private developers using concepts like transfer of development rights (TDR). But it is finally the government agency which will take care of the identification of the beneficiaries and the allotment of the housing units. There are different approaches and models available across the country where mutually beneficial partnerships have been worked out. The SEWS housing reserved land can be instrumental in addressing the demand of lower-income segments of housing market.

d. What about the slums existing on the SEWS reserved land? There is also an issue of the slum squatters existing on the SEWS reserved lands. There are two possibilities here. One, there is an existing slum and the planning authorities have declared the land of that slum as SEWS reservation. Second, there is a local politician led invasion on the public land which is going to be reserved for the poor. The implementation of TP Scheme takes a long time and thus, by the time, the TP Scheme is fully implemented slums come up on the lands reserved for the SEWS. In such cases, as per the GTPUD Act, if there are slum squatters existing on the reserved land, it needs to be removed first and only after building the housing units, the beneficiary may be allotted the residential units. The GTPUD Act should be amended in case of slum existing on the SEWS reservations where the existing slum itself could be redeveloped over a period of time giving land titles to the poor family over a period of time.

e. How to make the ‘reservation’ policy work? Will the 25 per cent of land earmarked for the poor work for them?

Reserving land for the poor has not really worked in the past in one of the most urbanised state in the country and her main city (Ahmedabad), which is leading in JnNURM project allocations and implementation. The TP Schemes only reserved the land but beyond that no institutional arrangement was developed nor institutional accountability introduced to ensure that the land are indeed used for housing the poor. The existing slum development departments of the urban local bodies can be provided with the financial and administrative resources to develop housing projects for the poor on the reserved land. It is a mandatory reform of JnNURM to earmark 25

per cent of land for housing the poor. Here, we saw an example where 10 per cent of land reservations in the local area plans are not taken care of then managing 25per cent of land reservations would be even more difficult in the existing circumstances. There needs to be institutional mechanism and accountabilities to be established to provide housing and basic services for the poor otherwise the goals of this mandatory reform would not be achieved.

Policy implications – making planning work for the poor

The proliferation of informal and illegal forms of access to urban land and housing has been one of the main consequences of the processes of social exclusion and spatial segregation characterized as intensive urban growth in the city. Absence of adequate housing policy and the land market dynamics force the urban poor to create their own shelter by encroaching upon the vacant land and construct their own housing. To prevent the growth of slums, there is a need to understand and identify the factors that have contributed to the phenomena of urban illegality. The local authority should explore practical but transparent methods to promote better utilization of public purpose land while improving access for the urban poor. The efficiency of town planning and urban development programmes lies in meeting the growing demand for housing in urban areas that ensure orderly urban growth. Private sector involvement has been applied in different cities which give the efficiency in the implementation process.

The government should use all possible ways of making land and housing available to the urban poor. If the land is utilised efficiently the quantum of land required for the urban poor in the city of Ahmedabad is not much compared to the size of the city. To house about one million urban poor (2 lakh households) in the city the gross land requirement is about 10 sq. kms. For an urban agglomeration of Ahmedabad, which is more than 700 sq kms, it is not difficult to find about 10 sq kms of land distributed across the entire agglomeration.

The city level DP and the area level TP Scheme are the formal and most important mechanisms to earmark land for the poor time to time. They should play an active role in providing for the poor. Planning authorities should make sure that these plans are timely revised and sanctioned. The new township policy in the Gujarat State would allow large scale housing projects possible and the government should make sure that there are pro-poor components in such projects.

The TP Schemes in Gujarat have proved to be successful instruments in reserving lands for infrastructure project and the same can be used effectively to allocate lands for the poor. The state government should encourage the city government to develop land pools which could be utilised for the benefit of the urban poor.

References:

1. AMC and AUDA with CEPT University (2006). City Development Plan.- Ahmedabad. Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation and Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority, Ahmedabad.

2. AUDA (2006): Draft Development plan of AUDA-2011. Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority, Ahmedabad.

3. Kundu, Amitabh and Mahadevia Darshini (2002), ‘Ahmedabad–Poverty and Vulnerability in a Globalizing Metropolis’, Manak Publications, New Delhi.

4. MoUD (2005): Guideline for the project on Basic services to urban poor, to be taken up under JNNURM, Ministry of Urban Development, GOI, New Delhi

5. MoHUPA (2007): National Urban Housing and Habitat Policy 2007. Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, GOI, New Delhi.

6. MoHUPA (2007): National Urban Housing and Habitat Policy, 2005, September 6, 2005. Source: muepa.nic.in/policies/duepa/DraftNHHP2005-9.pdf.

7. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2003), The Challenge of Slums, Earthscan Publications Ltd., London