CSR Disclosure, Visibility and Media Pressure...

Transcript of CSR Disclosure, Visibility and Media Pressure...

European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences ISSN 1450-2275 Issue 93 February, 2017 © FRDN Incorporated http://www.europeanjournalofeconomicsfinanceandadministrativesciences.com

CSR Disclosure, Visibility and Media Pressure International

Evidence from the Apparel and Textile Industry

Andrea Lucchini

Department of Economics and Management

University of Pavia, Italy

Anna Maria Moisello

Corrisponding author, Department of Economics and Management

University of Pavia, Italy

E-mail: annamaria. moisello@unipv. it Tel. +39-382-986247

Abstract

This paper studies how pressure and visibility affect Corporate Social

Responsibility (CSR) disclosure for companies indirectly exposed to a high risk of legitimation gap, by the means of their suppliers’ actions. It analyzes how different forms of visibility and pressure affect a firm’s CSR disclosure behavior using an international dataset of 40 companies, from the apparel and textile industry, during the period 2006-2015. We construct a continuous disclosure weighted index covering organizational, stakeholder, ethical, economic, environmental and social issues. We find that size and media exposure significantly affect social disclosure from one year to another within the same firm, while international presence and media pressure enhance the level of corporate disclosure between companies.

Keywords: Corporate Social Responsibility, CSR disclosure, Legitimacy Theory, Stakeholder Theory, Visibility, Pressure

JEL: M14, M41, M10, G30

Introduction Societal expectations about corporate activities are increasing by the day. Companies are no longer seen as having only economic responsibilities within the boundaries established by law; they also have to operate following ethical guidelines. If they fail to do so, society, and more specifically corporate stakeholders, are likely to withdraw their support and the legitimacy that allows companies to survive (Dowling and Pfeffer, 1975).

Literature suggests that,if consumers are aware of them, CSR activities have a significant impact on attitudes toward a brand and on purchasing intent (Pomering and Dolnicar, 2009). Empirical findings point out that positive CSR associations favorablyaffect a new product’s evaluation through their influence on corporate evaluation, while negative CSR associations may exert a detrimental influence on the overall product evaluation (Brown and Dacin, 1997). There is evidence that the internal and external communication of CSR commitment is associated with enhanced levels of employee commitment, customer loyalty, and business performance (Maignan et al. , 1999). Moreover, empirical studies suggest that CSR announcements are viewed positively by investors, influencing

6 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

stock prices (Arya, B. , and Zhang, G. , 2009), there is a growing demand for social responsibility in mergers and acquisitions (Ciambotti et al. ,2011) and firms are more prone to disclose their socially responsible behavior when they are planning to issue equity and bonds (Gavana et al. , 2017). Nevertheless, literature highlights that companies which most display their ethical and social goals are more likely to be critically observed by stakeholders (Ashfort and Gibbs, 1990). Stakeholders’ increased attention to the impact of a firm’s operation on the environment and society implies a growing need for information on companies’ socially responsible behavior and stimulates firms’ commitment to CSR reporting (Van der Laan Smith et al. , 2005).

Several studies have analyzed firms’ decision to communicate social and environmental information, finding that visibility exposes companies to stakeholder pressure which is the main reason behind the adoption of sustainability disclosure (Patten, 2002; Cormier and Magnan, 2003; Branco and Rodrigues, 2008; Brown and Deegan, 1998). The extent of CSR disclosure provided by a company would indicate the importance it attaches to societal and environmental issues (Chan et al. , 2014) and a firm would use disclosure in order to communicate its CSR commitment or to manipulate the perception of its CSR performance (Ling et al, 2013).

Some studies concentrate on firms belonging to environmentally-sensitive industries, which are more subject to a legitimacy gap caused by their direct actions (e. g. Neu et al, 1998; Brown and Deegan, 1998; Li et al, 1997); other studies take into account different industries, focusing either on an inter-firm (Ayadi, 2004; Branco and Rodrigues, 2008; Garcìa-Ayuso and Larrinaga, 2003) or in an intra-firm analysis of one or two companies (Campbell, 2000; Islam and Deegan, 2010) and reporting a short period of observations.

Nowadays, CSR concerns are related not only to environmentally or ethically-sensitive industries but also take into account issues, such as child labor and sweatshops, which can affect many industries (Morsing and Schulze, 2006). Stakeholders pay great attention not only to a company’s direct actions but also to suppliers’ behaviors that may prompt criticism toward a firm (Morsing and Schulze, 2006).

To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies focusing on CSR disclosure in industries that are most likely to suffer a legitimacy gap indirectly, by means of suppliers’ actions, such as the apparel and textile businesses.

Few apparel and textile companies are vertically integrated and they rarely engage with issues related, for example, to raw material extraction and agriculture; factorsthat raise relevant problems in terms of worker exploitation and environmental damage. Therefore, CSR managers experience great difficulties in controlling noncompliance problems further down the supply chain in order to avoid sweatshops being set up (Welford and Frost, 2006). This means that apparel and textile industries may be subject to severe pressures from stakeholders, as they have been, and continue to be, highly criticized for their poor performance regarding social issues, not only in their own factories and but also in those owned by their suppliers.

There is evidence that this industry has long been aware of the relevance of CSR (Marvel, 1977; Smith, 2003). It used CSR in the context of political strategies, imposing it on rivals who did not employ adequate technology, raising their costs and resulting in regulatory barriers to imitation (McWilliams et al. , 2006). As a matter of fact, the first child labor law was passed in Great Britain in the early 1800s after the textile companies, who employed modern technology, lobbied for restrictions on child labor, which was used more by the older and smaller firms (Marvel, 1977). Moreover, the literature points out that some of the textile industry’s forward-thinking entrepreneurs from this erawereaware that firms have societal obligations and new industrial communities, with houses for workers, churches, schools and hospitals, were created on the initiative of those entrepreneurs (Smith, 2003).

7 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Therefore, given that no studies have yet done so, it is of interest to study how pressure and visibility affect CSR reporting,over time, for companies indirectly exposed to the risk of a legitimation gap as their voluntary disclosure behavior is largely unexplored.

We address this gap by drawing on legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory. According to legitimacy theory (Dowling and Pfeffer, 1975), a company has to operate following societal expectations. If this does not happen, a legitimacy gap is likely to arise, eventually leading to the withdrawal of the company’s legitimacy, thus threatening its survival. Firms disclose their socially-responsible behavior because of the pressure stemming from various societal groups, in order to demonstrate that they behave consistently with societal values and beliefs (Hooghiemstra, 2000) and therefore they may legitimately continue their operations. CSR reporting is a means of influencing the public’s perception of the firm (Brown and Deegan, 1998). Stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984) points out that society is not a homogeneous entity and it consists of different societal groups. Within this framework, CSR disclosure is the means to satisfy these eventual expectations or change a firm’s perception of particular stakeholders (Deegan, 2002).

We analyze how different forms of visibility and pressure affect a firm’s CSR disclosure behavior using a longitudinal international dataset of 40 companies, operating in the apparel and textile industry, during the period 2006-2015. In order to measure the level of social disclosure, we build a continuous disclosure index covering organizational, stakeholder, ethical, economic, environmental and social issues. A weighted index is used to overcome the main weaknesses of other evaluating instruments used to score corporate reports, such as word counting (Neu et al, 1998; Williams and Ho Wern Pei, 1999) and unweighted index (Hossain et al, 2006) - which fail to deal with companies’ greenwashing. We use size, international presence, age, media exposure and media pressure as visibility proxies, as well as some control variables.

We contribute to CSR literature by focusing on the apparel and textile industry which, indirectly,is at a high risk of a legitimation gap. Our findings suggest that within the same firm, size and media exposure significantly affect social disclosure from one year to another; while international presence and media pressure influence positively the different level of corporate disclosure between companies.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: chapter 1 addresses the theoretical framework, literary review and the hypothesis definition; chapter 2 presents data and methods; chapter 3 provides the empirical results; chapter 4 discusses the main results and chapter 5 concludes by pointing out practical implications and limitations,while also providing suggestions for further research.

1. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development Legitimacy and Stakeholder Theory

Legitimacy theory is, along with stakeholder theory, one of the most popular theoriesused to analyze the behavior of a company dealing with corporate social responsibility. One of the clearest and most complete definition of legitimacy is provided by Suchman (1995), who states that “legitimacy is a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed systems of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions”. Legitimacy is, therefore, something that companies cannot assign to themselves, on the contrary they have to act according to a set of beliefs and values that are established by the society (Hooghiemstra, 2000), in order to be perceived as legitimate.

Moreover, it appears clear that legitimacy is something that companies may have today but may not have in the future if they fail to maintainbehavior in compliance with society’s values and beliefs (Sethi, 1979), which, in turn, are subject to continuous change.

However, societal values and beliefs is such a broad term that it risks becoming too complicated and vague for managers to deal with and can result in the idea behind CSR being

8 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

misunderstood. Stakeholder theory points out that society is made up of different groups of individuals characterized by different expectations in terms of a firm’s actions and exercising different levels of power in influencing its behavior (Deegan, 2002).

Corporations do not have to answer for, or be accountable for, every social problem but only those related to their stakeholders (Clarkson 1995; Wood, 1991). They engage in the fulfilment of their expectations (Haniffa and Cooke, 2005). Wood highlights that “stakeholder analysis provided a starting point for scholars to think about how society grants and takes away corporate legitimacy”, specifying that “if central stakeholders lose confidence in the firm’s performance, legitimacy may be withdrawn” (Wood, 1991). Thissentence states that in order to understand and classify society’s expectations, a company needs to understand stakeholders’ needs, and that it is the central stakeholders who may decide to revoke the legitimacy.

According to Suchman (1995), there are three types of legitimacy: pragmatic, moral and cognitive.

Pragmatic legitimacy results from the self-interested calculation made by a company’s stakeholders. They will concede legitimacy to an organization as long as they perceive that they will benefit from corporateactivities (Palazzo and Scherer, 2006). Therefore, the corporation has to attempt to influence stakeholders and persuade them about the usefulness of its activities. This can be done through stakeholders’ involvement in corporate decision-making and through a careful management of public relations and communication (Prado-Lorenzo et al. , 2009)

In the apparel sector, a form of pragmatic legitimacy is given to unethical companies by some customers, which tend to justify, or at least not to criticize, those companies involved in sweatshop scandals as long as they receive the benefit of lower prices (Ha and Lennon, 2006).

Moral legitimacy does not rest on a self-interest calculation but rather on “positive normative evaluation of the organization and its activities” (Suchman, 1995). Thus, these judgements are based on the effective evaluation of corporate activities and are expected to be resistant to a firm’s attempts to manipulate and influence stakeholders in the evaluation process. Stakeholders judge an organization as legitimate if “socially acceptable goals in a socially acceptable manner” are pursued (Ashforth and Gibbs, 1990). Stakeholders’ attention is not limited to a firm’s direct behavior, but also focuses on the actions of its consumers and suppliers, as in the case of Nike, a company that that has been strongly criticized for its suppliers’ working conditions (Morsing and Schultz, 2006). Cognitive legitimacy emerges when stakeholders repute the organization, and its activities, as “inevitable and necessary” and the “acceptance is based on some broadly shared taken-for-granted assumptions” (Palazzo and Scherer, 2006).

Cognitive legitimacy has little chance of being influenced and managed by the organization, as it operates mainly in the subconscious of the constituencies. Therefore, the firm would do better to simply adapt to social expectations, without trying to manipulate those stakeholders, as, if the attempt is disclosed, cognitive legitimacy would collapse (Palazzo and Scherer, 2006) and they would begin an active opposition to corporate activities. It appears clear that in moving from pragmatic to the moral to the cognitive, legitimacy becomes increasingly more difficult to manipulate but also becomes more stable once established (Suchman, 1995).

Stakeholders perceive legitimate organizations as more worthy, meaningful, more predictable and more trustworthy (Suchman, 1995). Consequently, if an organization is perceived as being non-legitimate, it is likely to face several problems in the relationships with its stakeholders: customers may stop buying its products, shareholders might withdraw their money; media and social activist groups may decide to start negative campaigns and boycott the companies’ products; and local communities may decide not to concede to the company the possibility to operate there. It appears clear that in order to survive, a corporation has to maintain its legitimacy (Husted, 1998; Branco and Rodrigues, 2006).

However, it may be that, at a given time, corporate behaviors differ from stakeholders’ expectations. This is when a legitimacy gap is likely to arise(Sethi, 1979, Oliver, 1991, Scott, 1987). Managers may react strategically to this according to how the hypothetical claim brought by a

9 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

stakeholder is perceived as salient: if the stakeholder is considered as fundamental, the firm would react by accommodating the request. However, if the stakeholder is considered as being less important, the expectation may be ignored and the company may decide not to take into consideration the threat or, simply, communicate symbolic engagement without taking significant steps into solving the problem (de Villiers and van Staden, 2006).

Moreover, managers have constantly to monitor the external environment and stakeholders’ expectations, without being too self-assured of the organization’s legitimacy and the way of achieving it (Suchman, 1995). For this reason, they should monitor multiple stakeholders’ interest and perceive possible change, involving stakeholders in the decision making of the firm (Prado-Lorenzo et al. , 2009). Further, companies should transform their legitimacy activities from episodic to continual, make the activities and the communication of the firm credible and engage in an effective CSR communication (Du et al. , 2010). Legitimacy and Disclosure

The strategic analysis of the stakeholder’s claim made by the manager is important in order to manage hypothetical legitimacy gaps. Dowling and Pfeffer (1975: 127) indicate three ways in which managers can deal with a legitimacy crisis, thus legitimizing corporate activities:

• Adapt output, goals and methods

• Communicate to change societal expectations

• Communicate to identify with symbols, values or institutions with legitimacy The last two methods involve a communication of the company’s commitment, and it is usually

made through the sustainability or annual report. The first method does not really address the legitimacy threat if the society is not made aware of the change (de Villiers and van Staden, 2006).

The fact that “legitimacy management rests heavily on communication” (Suchman, 1995) is confirmed by several authors. For example, Gray et al (1995) state that: “information is a major element that can be employed by the organization to manage (or manipulate) stakeholders in order to gain their support and approval or to distract their opposition and disapproval”. So, for an action to be effective, it needs publicity, and the disclosure of environmental and social information are methods by which managers may try to align public expectations with a company’s actions (Patten, 1991).

Newson and Deegan (2002) state that “legitimacy is assumed to be influenced by disclosures of information and not simply by (undisclosed) changes in corporate actions” therefore firms may use CSR disclosure in order to gain, maintain or repair legitimacy (Patten, 1991; O’ Donovan, 2002).

On the one hand, a company may retain legitimacy even if it is acting contrary to stakeholders’ expectations if theirbehavior goes unnoticed (short-run situation). On the other hand, a company may fail to receive legitimacy although it is behaving according to values and beliefs of the stakeholders if such behavior is not correctly communicated or stakeholders fail to notice it. The extent of CSR disclosure provided by a company is perceived as an indicator of the importance the company attaches to societal and environmental issues (Chan et al. , 2014), therefore it is a means to communicate CSR commitment and might also be used in order to manipulate external stakeholders’perception of a firm’s CSR performance (Ling et al, 2013).

CSR disclosure has been highlighted as the most effective way an organization has to communicate its commitment towards stakeholders’ values and expectations, thus reducing political, social and economic exposure and pressure (Patten, 1991). In fact, through CSR disclosure, companies can demonstrate that “their actions are legitimate and that they have behaved as good corporate citizens (Hooghiemstra, 2000). Information on a firm’s good CSR performance improves consumers’ brand evaluation (Pomering and Dolnicar, 2009; Brown and Dacin, 1997). CSR communication also affects investors’ perceptions and there is empirical evidence that firms tend to use CSR disclosure in order to facilitate bond and equity issues (Gavana et al. , 2017)

As a matter of fact,as time goes by, there has been an increase in the disclosure of environmental and social information in the sustainability and annual reports made by firms (Adam &

10 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Frost, 2008), although a great deal of effort is still needed in order to better integrate CSR and financial information (Pesci and Andrei, 2011). However, disclosure is not a cost-free practice: it requires the measurement and verification of social and environmental impacts and the publication of such information (Verrecchia, 1983; Li et al. , 1997; Cormier and Magnan, 1999) so companies are involved in a cost and benefit analysis (Brammer and Pavelin, 2008), which is likely to vary with pressure from external agents.

Within the legitimacy theory framework, the amount and quality of disclosure is likely to change as a result of the degree of public scrutiny of the firm (Garcìa-Ayuso and Larrinaga, 2003).

The pressure that stakeholders exercise on the company is influenced by some characteristics of the company itself, and legitimacy theory’s studies found visibility to be related to corporate social disclosure (Branco and Rodrigues, 2006). Some characteristics of thefirm may be used to represent its visibility, such as size, age, international presence and media exposure and pressure, as has been done by several authors (Patten, 2002; Cormier and Magnan, 2003; Branco and Rodrigues, 2008; Brown and Deegan, 1998). Size

Larger firms, in fact, tend to be more visible to the general public than smaller ones, and are thus subject to greater pressure from external stakeholders (Belkaoui and Karpik, 1989; Brown and Deegan, 1998) and face higher risks of running into a legitimacy gap. Bigger companies’ CSR managers must face great difficulties in controlling noncompliance problems related to the supply chain in order to avoid sweatshops (Welford and Frost, 2006), which closely involved the reputation of firms operating in the textile and apparel industry (Morsing and Schultz, 2006). One of the problemswith this situation is that “legitimacy crises tend to become self-reinforcing” (Suchman, 1995): stakeholders become suspicious about a company’s activities although the legitimacy gap has been closed, and the company is likely to be subjected to a high degree of scrutiny in each of its operations.

Stakeholders are likely to have higher expectations from large firms as they are more visible (Brammer and Pavelin, 2008) and have achieved the economic efficiency that should allow them to employ a percentage of their resources for social and environmental issues. In the same way, the impact on social and environmental matters of large firms’ policies is greater than those of smaller ones, thus stimulating bigger companies to be better sustainability communicators (Gavana et al. , 2016).

Therefore, larger companies may consider social disclosure and corporate social responsibility as a way to improve their reputation (Branco and Rodrigues, 2008).

H1a: There will be a positive relationship between size and CSR disclosure within the same company

H1b: Larger companies are likely to disclose more than smaller ones Age

Older firms tend to be more visible to stakeholders because they are likely to have had a greater impact on society than relatively younger firms. They are also used to having better economic performance than younger companies. Roberts (1992) finds a significant positive relationship between a firm’s age and environmental disclosure and suggests that asa company matures, its reputation and history of involvement in CSR activities are strictly linked stakeholder expectations in terms of CSR are high and CSR sponsorship withdrawal could signal to stakeholders that the firm expects to face financial or managerial difficulties.

Moreover, younger firms are likely to have fewer issues to report than older ones (Yao et al. , 2011).

These reasons should encourage older companies to disclose more information than younger ones in order to meet stakeholders’ expectations.

H2: Older companies are likely to disclose more than younger ones

11 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

International Presence

Multinational companies operating in multiple countries may have to face different perceptions of legitimacy according to the country in which they are operating. In fact, “on the global playing field, there are no broadly accepted normative standards, neither in legal, nor in moral terms” (Habermas, 2001, as cited in Suchman, 1995).

Some activities may be perceived as legitimate in the host country but not in the home country of the company, thus creating a dilemma in the firm on which activities to pursue and which not (Barkemeyer, 2007).

Internationalized firms face different systems of ethical rules and values and literature provides evidence that the case in foreign listings, the presence of international stakeholders, increases CSR disclosure (Gamerschlag et al. , 2011; Hackston and Milne, 1996). Firms exporting their products abroad have to answer to different customer needs according to their values and culture, and to different laws and regulations that govern trade within different countries. (Branco and Rodrigues, 2008).

Companies that operate internationally will face a denser stakeholder network and are likely to be in a less central position within it. For this reason, they have to balance their strategies, taking into consideration different stakeholder expectations in different countries. They are also likely to face more difficulties in imposing their norms.

Internationalization requires a deeper analysis and balance of the different interests that stakeholders have in different countries, and if the risk of losing legitimacy is high, the firm should adopt the higher standards of CSR from a developed country and renounce the benefits, in terms of the lower costs that adopting the lower standards from a developing country would bring.

Moreover, visibility increases along with foreign presence as the company is also likely to become known in the new countries where it is operating. As the firm diversifies its activities internationally, the dimension of the contact between it and the society is going to increase too.

So, companies that have operations in foreign countries should disclose more information than those operating in the domestic country.

H3a: There will be a positive relationship between international presence and CSR disclosure within the same company

H3b: Companies that sell more products at the international level are likely to disclose more than companies that focus more on the domestic market Media Exposure

Companies that are more reported in the newspapers face higher visibility and, for this reason, are likely to be scrutinized more by stakeholders. The media has an influential role in increasing public attention on firms’ actions, thus influencing public perceptions about firms’ activities and eventually generating a legitimacy gap (Garcìa-Ayuso and Larrinaga, 2003). Media coverage increases the companies’ visibility (Bansal, 2005) putting them under the lens of public scrutiny. Media play a relevant role in disclosing corporate information for stakeholders (Brown and Deegan, 1998). The power of media has been noted by several researchers, such as Patten (2002), Brown and Deegan (1998), Gamerschlag et al. , (2011) and Reverte, (2009) who state that increased media attention leads to increased pressure.

Moreover, if a company is cited it means that it is having some impact on the society, either positive or negative. It becomes an easy target for stakeholders’ judgments and it has to disclose more information about its activities in order to avoid a legitimacy gap arising.

H4: There will be a positive relationship between the level of exposure a firm has in the media and CSR disclosure within the same company

12

Media Pressure

Media pressure is used as a proxy for negative publicity a firm is facing, thus representing an alarm bell of which companies should take serious notice

social activist groups, who may start promoting boycotts of the company’s product, thus damaging its corporate image and reputation

to show stakeholders that they are taking important steps in the right direction, aligning their actions with societal values and beliefs (Islam and Deegan, 2010)

associate to both media coverage and the level of negative print media coverage

face less negative visibility in the media

2. Sample

The first step in the study was to select a consistent number of companies in the apparel and textile sector that disclosed information about their activities in the period 2006consulted was primarily that provided bythings, collect social reports that companies sendto themsector of interest, which was mainly the apparel and textile sectordatabase is that it only collects information from companies that send reportsto them; companies that are expected to satisfy and follow GRIreporting guidelineschecked each company’swebpagesto verify whethernot appear on the GRI websitesearched the database of the Clean Clothes Campaign and that of the United Nations Global Compact, anotherimplementation of ten social and environmental principles, and that reports the name of the companies that adhere to it

apparel and textile sector that were found in the UNGC website and we checked their official webpages to see if they provided a report from 2006 to 2015

2006to 400

12

Media Pressure

Media pressure is used as a proxy for negative publicity a firm is facing, thus representing an alarm bell of which companies should take serious notice

Companies that face higher pressure from the medsocial activist groups, who may start promoting boycotts of the company’s product, thus damaging its corporate image and reputation

Companies are likely to respond to such pressure by disclosing more social infoto show stakeholders that they are taking important steps in the right direction, aligning their actions with societal values and beliefs (Islam and Deegan, 2010)

Brown and Deegan (1998) partially confirmed that the level of environmentaassociate to both media coverage and the level of negative print media coverage

H5: Companies that face higher media pressure are likely to disclose more than companies that face less negative visibility in the media

2. Data and MethoSample

The first step in the study was to select a consistent number of companies in the apparel and textile sector that disclosed information about their activities in the period 2006consulted was primarily that provided bythings, collect social reports that companies sendto themsector of interest, which was mainly the apparel and textile sectordatabase is that it only collects information from companies that send reportsto them; companies that are expected to satisfy and follow GRIreporting guidelineschecked each company’swebpagesto verify whethernot appear on the GRI websitesearched the database of the Clean Clothes Campaign and that of the United Nations Global Compact, another initiative that encourages companies to adopt more sustainable politics through the implementation of ten social and environmental principles, and that reports the name of the companies that adhere to it

After that, the same process as before was followapparel and textile sector that were found in the UNGC website and we checked their official webpages to see if they provided a report from 2006 to 2015

Finally, the number of companies which satisfied the re2006-2015 amounted to 40, bringing the total number of observations (reports that have been analysed) to 400.

European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Media Pressure

Media pressure is used as a proxy for negative publicity a firm is facing, thus representing an alarm bell of which companies should take serious notice

Companies that face higher pressure from the medsocial activist groups, who may start promoting boycotts of the company’s product, thus damaging its corporate image and reputation

Companies are likely to respond to such pressure by disclosing more social infoto show stakeholders that they are taking important steps in the right direction, aligning their actions with societal values and beliefs (Islam and Deegan, 2010)

Brown and Deegan (1998) partially confirmed that the level of environmentaassociate to both media coverage and the level of negative print media coverage

H5: Companies that face higher media pressure are likely to disclose more than companies that face less negative visibility in the media

Data and Methods

The first step in the study was to select a consistent number of companies in the apparel and textile sector that disclosed information about their activities in the period 2006consulted was primarily that provided bythings, collect social reports that companies sendto themsector of interest, which was mainly the apparel and textile sectordatabase is that it only collects information from companies that send reportsto them; companies that are expected to satisfy and follow GRIreporting guidelineschecked each company’swebpagesto verify whethernot appear on the GRI websitesearched the database of the Clean Clothes Campaign and that of the United Nations Global Compact,

initiative that encourages companies to adopt more sustainable politics through the implementation of ten social and environmental principles, and that reports the name of the companies that adhere to it.

After that, the same process as before was followapparel and textile sector that were found in the UNGC website and we checked their official webpages to see if they provided a report from 2006 to 2015

Finally, the number of companies which satisfied the re2015 amounted to 40, bringing the total number of observations (reports that have been analysed)

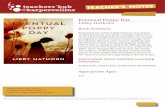

Figure 1

European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Media pressure is used as a proxy for negative publicity a firm is facing, thus representing an alarm bell of which companies should take serious notice

Companies that face higher pressure from the medsocial activist groups, who may start promoting boycotts of the company’s product, thus damaging its corporate image and reputation.

Companies are likely to respond to such pressure by disclosing more social infoto show stakeholders that they are taking important steps in the right direction, aligning their actions with societal values and beliefs (Islam and Deegan, 2010)

Brown and Deegan (1998) partially confirmed that the level of environmentaassociate to both media coverage and the level of negative print media coverage

H5: Companies that face higher media pressure are likely to disclose more than companies that face less negative visibility in the media

ds

The first step in the study was to select a consistent number of companies in the apparel and textile sector that disclosed information about their activities in the period 2006consulted was primarily that provided bythings, collect social reports that companies sendto themsector of interest, which was mainly the apparel and textile sectordatabase is that it only collects information from companies that send reportsto them; companies that are expected to satisfy and follow GRIreporting guidelineschecked each company’swebpagesto verify whethernot appear on the GRI website. Unsatisfied by the number of companies foundon the GRI database, we searched the database of the Clean Clothes Campaign and that of the United Nations Global Compact,

initiative that encourages companies to adopt more sustainable politics through the implementation of ten social and environmental principles, and that reports the name of the companies

After that, the same process as before was followapparel and textile sector that were found in the UNGC website and we checked their official webpages to see if they provided a report from 2006 to 2015

Finally, the number of companies which satisfied the re2015 amounted to 40, bringing the total number of observations (reports that have been analysed)

Figure 1: Geographical distribution of analyzed companies

European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Media pressure is used as a proxy for negative publicity a firm is facing, thus representing an alarm bell of which companies should take serious notice

Companies that face higher pressure from the medsocial activist groups, who may start promoting boycotts of the company’s product, thus damaging its

Companies are likely to respond to such pressure by disclosing more social infoto show stakeholders that they are taking important steps in the right direction, aligning their actions with societal values and beliefs (Islam and Deegan, 2010)

Brown and Deegan (1998) partially confirmed that the level of environmentaassociate to both media coverage and the level of negative print media coverage

H5: Companies that face higher media pressure are likely to disclose more than companies that face less negative visibility in the media

The first step in the study was to select a consistent number of companies in the apparel and textile sector that disclosed information about their activities in the period 2006consulted was primarily that provided by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which, among other things, collect social reports that companies sendto themsector of interest, which was mainly the apparel and textile sectordatabase is that it only collects information from companies that send reportsto them; companies that are expected to satisfy and follow GRIreporting guidelineschecked each company’swebpagesto verify whether

Unsatisfied by the number of companies foundon the GRI database, we searched the database of the Clean Clothes Campaign and that of the United Nations Global Compact,

initiative that encourages companies to adopt more sustainable politics through the implementation of ten social and environmental principles, and that reports the name of the companies

After that, the same process as before was followapparel and textile sector that were found in the UNGC website and we checked their official webpages to see if they provided a report from 2006 to 2015

Finally, the number of companies which satisfied the re2015 amounted to 40, bringing the total number of observations (reports that have been analysed)

Geographical distribution of analyzed companies

European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Media pressure is used as a proxy for negative publicity a firm is facing, thus representing an alarm bell of which companies should take serious notice.

Companies that face higher pressure from the media are likely to become an easy target for social activist groups, who may start promoting boycotts of the company’s product, thus damaging its

Companies are likely to respond to such pressure by disclosing more social infoto show stakeholders that they are taking important steps in the right direction, aligning their actions with societal values and beliefs (Islam and Deegan, 2010).

Brown and Deegan (1998) partially confirmed that the level of environmentaassociate to both media coverage and the level of negative print media coverage

H5: Companies that face higher media pressure are likely to disclose more than companies that

The first step in the study was to select a consistent number of companies in the apparel and textile sector that disclosed information about their activities in the period 2006

the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which, among other things, collect social reports that companies sendto them. On the website, it was possible to select the sector of interest, which was mainly the apparel and textile sectordatabase is that it only collects information from companies that send reportsto them; companies that are expected to satisfy and follow GRIreporting guidelineschecked each company’swebpagesto verify whether they have reports for the years 2006

Unsatisfied by the number of companies foundon the GRI database, we searched the database of the Clean Clothes Campaign and that of the United Nations Global Compact,

initiative that encourages companies to adopt more sustainable politics through the implementation of ten social and environmental principles, and that reports the name of the companies

After that, the same process as before was followed: we noted the name of the companies in the apparel and textile sector that were found in the UNGC website and we checked their official webpages to see if they provided a report from 2006 to 2015.

Finally, the number of companies which satisfied the re2015 amounted to 40, bringing the total number of observations (reports that have been analysed)

Geographical distribution of analyzed companies

European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Media pressure is used as a proxy for negative publicity a firm is facing, thus representing an alarm

ia are likely to become an easy target for social activist groups, who may start promoting boycotts of the company’s product, thus damaging its

Companies are likely to respond to such pressure by disclosing more social infoto show stakeholders that they are taking important steps in the right direction, aligning their actions

Brown and Deegan (1998) partially confirmed that the level of environmentaassociate to both media coverage and the level of negative print media coverage

H5: Companies that face higher media pressure are likely to disclose more than companies that

The first step in the study was to select a consistent number of companies in the apparel and textile sector that disclosed information about their activities in the period 2006

the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which, among other On the website, it was possible to select the

sector of interest, which was mainly the apparel and textile sector. The main shortcoming ofdatabase is that it only collects information from companies that send reportsto them; companies that are expected to satisfy and follow GRIreporting guidelines. In order to overcome this problem, we

they have reports for the years 2006Unsatisfied by the number of companies foundon the GRI database, we

searched the database of the Clean Clothes Campaign and that of the United Nations Global Compact, initiative that encourages companies to adopt more sustainable politics through the

implementation of ten social and environmental principles, and that reports the name of the companies

ed: we noted the name of the companies in the apparel and textile sector that were found in the UNGC website and we checked their official

. Finally, the number of companies which satisfied the request of having a report for the period

2015 amounted to 40, bringing the total number of observations (reports that have been analysed)

Geographical distribution of analyzed companies

European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Media pressure is used as a proxy for negative publicity a firm is facing, thus representing an alarm

ia are likely to become an easy target for social activist groups, who may start promoting boycotts of the company’s product, thus damaging its

Companies are likely to respond to such pressure by disclosing more social infoto show stakeholders that they are taking important steps in the right direction, aligning their actions

Brown and Deegan (1998) partially confirmed that the level of environmentaassociate to both media coverage and the level of negative print media coverage.

H5: Companies that face higher media pressure are likely to disclose more than companies that

The first step in the study was to select a consistent number of companies in the apparel and textile sector that disclosed information about their activities in the period 2006-2015. The database that was

the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which, among other On the website, it was possible to select the

The main shortcoming ofdatabase is that it only collects information from companies that send reportsto them; companies that

In order to overcome this problem, we they have reports for the years 2006

Unsatisfied by the number of companies foundon the GRI database, we searched the database of the Clean Clothes Campaign and that of the United Nations Global Compact,

initiative that encourages companies to adopt more sustainable politics through the implementation of ten social and environmental principles, and that reports the name of the companies

ed: we noted the name of the companies in the apparel and textile sector that were found in the UNGC website and we checked their official

quest of having a report for the period 2015 amounted to 40, bringing the total number of observations (reports that have been analysed)

Geographical distribution of analyzed companies

European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Media pressure is used as a proxy for negative publicity a firm is facing, thus representing an alarm

ia are likely to become an easy target for social activist groups, who may start promoting boycotts of the company’s product, thus damaging its

Companies are likely to respond to such pressure by disclosing more social information in order to show stakeholders that they are taking important steps in the right direction, aligning their actions

Brown and Deegan (1998) partially confirmed that the level of environmental disclosure was

H5: Companies that face higher media pressure are likely to disclose more than companies that

The first step in the study was to select a consistent number of companies in the apparel and textile The database that was

the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which, among other On the website, it was possible to select the

The main shortcoming of the GRI database is that it only collects information from companies that send reportsto them; companies that

In order to overcome this problem, we they have reports for the years 2006-2015 that do

Unsatisfied by the number of companies foundon the GRI database, we searched the database of the Clean Clothes Campaign and that of the United Nations Global Compact,

initiative that encourages companies to adopt more sustainable politics through the implementation of ten social and environmental principles, and that reports the name of the companies

ed: we noted the name of the companies in the apparel and textile sector that were found in the UNGC website and we checked their official

quest of having a report for the period 2015 amounted to 40, bringing the total number of observations (reports that have been analysed)

European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Media pressure is used as a proxy for negative publicity a firm is facing, thus representing an alarm

ia are likely to become an easy target for social activist groups, who may start promoting boycotts of the company’s product, thus damaging its

rmation in order to show stakeholders that they are taking important steps in the right direction, aligning their actions

l disclosure was

H5: Companies that face higher media pressure are likely to disclose more than companies that

The first step in the study was to select a consistent number of companies in the apparel and textile The database that was

the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which, among other On the website, it was possible to select the

the GRI database is that it only collects information from companies that send reportsto them; companies that

In order to overcome this problem, we 2015 that do

Unsatisfied by the number of companies foundon the GRI database, we searched the database of the Clean Clothes Campaign and that of the United Nations Global Compact,

initiative that encourages companies to adopt more sustainable politics through the implementation of ten social and environmental principles, and that reports the name of the companies

ed: we noted the name of the companies in the apparel and textile sector that were found in the UNGC website and we checked their official

quest of having a report for the period 2015 amounted to 40, bringing the total number of observations (reports that have been analysed)

13 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

As it is possible to see from the chart, the majority of the companies come from Europe and United States and Canada, namely the developed world.

This is not surprising as CSR is not cost-free and developing countries are likely to consider it as a luxury and prefer to concentrate more on economic matters.

On the contrary, almost all developed countries are approaching social and environmental issues very seriously, legally binding companies to respect rules and report about them. Dependent Variable

The first variable, which is used as a dependent variable in the regression, is the amount of disclosure that a company makes.

In order to select which report to analyze, we followed this procedure: if a company provided a sustainability report (which may have also been named as CSR report or social and environmental report) we evaluated it; if not the attention moved to the annual report, and, if this was unavailable, we checked the financial statement. News reported on the website and press releases are not taken into account because they usually provide far less information than reports, which are also subject to more specific regulation and audits, making this information more credible (Cormier et al, 2009; Aerts et al, 2008).

After that, the first author, in order to ensure homogeneity in the evaluation, made a content analysis of each report based on a weighted and continuous index that was previously built. First, he carefully read the report twice and then, to be sure that no issue had been forgotten,the “search” command available in the pdf document was used, writing the keyword and checking to see if it was in the document or not. Through this double-checking, it was possible to avoid the problem of failing to analyze an issue because it had not been noticed in the first two content readings. Finally, a third party reviewed the process in order to assure the evaluation’s consistency.

We decided to adopt such an approach to evaluate the amount of information disclosed as, although it is far lengthier than other kind of evaluation system, it allows us, at least partially, to eliminate the problem of greenwashing made by companies (Marquis and Toffel, 2012; Berrone et al. , 2015; Delmas and Burbano, 2011).

Credibility of CSR disclosure, in fact, has been subject to some critics (Tilt, 1994), who repute it to be mainly qualitative, without giving quantitative information on companies’ activities. In this way, poor-performing companies would report their social and environmental policies in a rhetorical way only to convince stakeholders that they are on the right path to fully implementing CSR within the company when, in reality, they are not taking any steps to do so. In order to avoid this problem, we preferred to abstain from using evaluating methods such as “words counting” (Neu et al, 1998; Williams and Ho Wern Pei, 1999) or using a completely unweighted index, which gives a value of 1 if the issue is reported and zero if it is not (Hossain et al, 2006), as they do not investigate fully the kind of information companies are disclosing, perhaps involuntarily helping them to greenwash. Such methods have some advantages: they do not take as long and are objective in nature; while our weighted index is subjective. However, the subjectivity of the indexwas notdeemed as a problem, because a third party’s review assured content analysis consistency across firms.

We took into consideration 56 disclosure items grouped into 8 categories or indicators: 2 for strategy, 13 for organizational profile, 4 for stakeholders’ engagement, 5 for governance, 2 items ethics and integrity, 4 economic indicators, 8 environmental indicators, 18 indicators. The items providing qualitative disclosure (strategy, organizational profile, stakeholders’ engagement, governance, ethics and integrity) was evaluated on a 0-1 scale: value 1 if the item is reported and 0 otherwise. This is because these issues are typically of this type: they can either be reported or not, but we cannot weigh them following some principles.

The remaining items, which are related to quantitative disclosure, were evaluated by a rating scale 0-6 with a point given for each of these conditions: 1) the item is reported; 2) comparison with other companies in the sector is made; 3) comparison with the past is made; 4) comparison with the objectives is made; 5) the data are presented both in absolute and relative terms; 6) the data are

14 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

presented in a disaggregated way (shops, plants, geographical area). These items are those that can allow us to make a stronger evaluation of the amount of information disclosed by companies, reducing the risk of greenwashing. The items, used in building this index,follow the guidelines from the Global Reporting Initiative and the principles of the AccountAbility 1000. The former is widely recognized as the leader among voluntary sustainability reporting systems (Brown et al. , 2007) and its guidelines are the most followed by companies worldwide; the latteris a standard developed by the Institute of Social and Ethical Accountability.

We gave different weight to the economic, environmental and social indicators, inserting only 4 issues in the first, 8 in the second, and 18 in the third, which brought the maximum possible score for the economic indicator to be 24 points, against the 48 for the environmental and 108 points for the social indicator. This choice reflects the idea behind the investigation of CSR disclosure in a sector like the apparel and textile one. First of all, the matter under scrutiny is sustainability so from here the decision to give less importance to economic performance. Secondly, in the apparel sector social issues have more relevance than the environmental ones. This is in line with the different weight the Dow Jones Sustainability Index gives to the economic, environmental and social performance according to the sector a company comes from.

In the organizational profile’s category six standards, which should help organizations in implementing CSR, are taken into consideration. The decision to consider each standard individually and not just as a unique item named “implementation of standard” and which would have had a value between 0 and 1 point, is justified by the increasing importance and attention these standards are acquiring, as their aim is to fill the gap that governmental regulation has left in the protection of the environment and workers due to the increasing globalized world (Albano et al, 2012; Christmann, 2004). Independent Variables

The independent variables that wereanalysed in this study are: size, age, international presence, media exposure, and media pressure. Data was collected using the Facset database, firms’ financial reports and the databases of certain publications (The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, Finland Times, Helsinki Times, SüddeutscheZeitung, El País, The Rio Times, Japan Times and SABC News, China Daily, BBC, The Economist and The Guardian. )

Revenues, total assets and the number of employees were taken by many studies as proxies for the firm’s size in studying CSR disclosure (Aerts et al, 2008; Cormier and Magnan, 2003; Cormier et al, 2004; Dawkins and Fraas, 2011; Lai et al, 2014, Branco and Rodrigues, 2008). As suggested byHackston and Milne (1996), there are no particular reasons to prefer one particular measurement of size, therefore we decided to use the natural logarithm of revenues. We use revenues as an explanatory variable of CSR disclosure both for the inter-firm and intra-firm level.

Companies’ age is the second independent variable, whose value increases by one each year of the observed period.

International presence was computed as the number of sales outside the country of origin on the total sales made by the company, expressed as a percentage (Bansal, 2005; Branco and Rodrigues, 2008; Ayadi, 2004).

���. ������� =Foreign sales

Total sales %

We will analyze both inter-firm and intra-firm trends. Media exposurewas defined as the number of articles a company has in the following

newspapers for the period 2006-2015: The Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, Finland Times, Helsinki Times, SüddeutscheZeitung, El País, The Rio Times, Japan Times and SABC News. The choice to count the number of articles to define the level of media exposure, and then of media pressure, has been used by a number of authors (Weaver et al. , 1999; Aerts et al. , 2008; Garcìa-Ayuso

15 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

and Larrinaga, 2003). The choice of the newspaper tends to reflect the geographical distribution of the sampling companies, with the inclusion of at least one newspaper for each represented continent. Moreover, due to the inclusion of the time variable in the regression, newspapers that did not report the dates, or that did not allow to filter for time period have not been taken into consideration. We have not carried out a content analysis of the articles, therefore media exposure is a proxy for social visibility (Brammer and Pavelin, 2008; Yao et al, 2011; Branco and Rodrigues, 2008) and not necessarily for public pressure. The values of media exposure were taken in logarithms as the distance between the minimums and the maximums values was extremely large, due to the poor media coverage of some companies, as opposed to certain others that are continually discussed in the newspapers.

Due to the fact that some observations had the value of media exposure as equal to zero, we had to make the logarithmic transformation as log(x+1), in order to avoid missing values.

Media exposure was included only in the within company regression, while, for the inter-firm regression, the media pressure variable has been used.

The last independent variable is media pressure and it is defined as the number of articles from 2006 to 2015 that we found, using as keywords the name of the company and ‘sweatshop’.

We decided to use the word sweatshopas it represents the main problem of the apparel and textile sector. The publications that were consulted are: Financial Times, Japan Times, China Daily, SABC News, BBC, The Economist and The Guardian. In this case, we made a content analysis of the articles to be sure that there was negative publicity for the reported company, and this effort proved to be efficient, as some articles that contained both the name of the company and the word ‘sweatshops’, were positive about the firm, either for its efforts in dealing with the problem or because it had never had anything to do with the issue. Owing to the very strict method of analysis that was adopted, many companies had the values of the variable as equal to zero for many years. For this reason, media pressure is included only in the inter-firm regression.

Several empirical studies have used profitability as a variable of CSR disclosure (Belkaoui, 1976; Cormier and Magnan 1999; Ingram and Frazier, 1980; Belkaoui and Karpik, 1989; Brammer and Pavelin, 2008; Patten, 1991; Carmona and Carrasco, 1988). We used firms’ ROA (return on assets)

��� =Net income

Total assets

ROA, defined as the ration between net income and total assets, has been used by several studies in this field as a proxy for profitability (Branco and Rodrigues, 2008; Belkaoui and Karpik, 1989).

Several studies have investigated companies’ country of origin as a possible explanatory variable for the different level of disclosure between firms, as reported by Ayadi (2004); Adams and Kuasirikun (2000); Belkaoui and Karpik (1989); Trotman and Bradley (1981), therefore we use it as contro variable. To construct the values of this qualitative characteristic the Country Sustainability Ranking, developed by RobecoSAM1, was used an “investment specialist focused exclusively on Sustainability Investing”. Thecountry sustainability score is based on 17 environmental, social and governance indicators, which receive a weight of 15%, 25% and 60% of the total score, respectively. The score ranges from 1 to 10, with the highest grade being 10 and the lowest 1 (RobecoSAM2). The ranking built by this company is composed of 62 countries and comprehends all the countries of our sample. As there are 62 countries in the rankings, we assigned the country of origin these values: 62 if the country ranks first; 61 if it ranks second, 60 if it ranks third, and so on until the last position which we scored with 1 point. Empirical Models

Panel data models analyze cross-sectional (between companies) and or time-series effects. These effects may be fixed or random (Park, 2010).

The fixed effects model is used when the interest is to analyze the impact of the variables within a company over time. Each company has its own characteristics (such as culture) that may or may not influence independent variables. The fixed effects model assumes that we need to control for

16 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

this. Itassumes that these time-invariant characteristics are unique to each company and should not be correlated with the others (Torres-Reyna, 2007).

The random effects model allows the impact of the variables, either within the company or across companies, to be captured. Unlike the fixed effects model, it assumes that variation across entities is random and uncorrelated with independent variables.

The between effects model is a sub-category of the random effects model: it estimates using the cross-sectional information in the data. It analyses the impact of the variables across companies, computing the variable means for each company.

Therefore, we ran two different regressions: one that accounts for the variation, in time, within the companies (fixed effects model) and one that analyses the impact of the independent variables on the dependent variable across different companies (between effects model).

However, before adopting the fixed effects model for the first regression, the Hausman test was run in order to verify whether the data fitted with the fixed or the random effects model.

In the Hausman test we have:

• H0: the unique errors are not correlated with other regressors

• H1: the unique errors are correlated with other regressors The dependent variable is the reporting value while the independent variables are: ln(revenues),

ln(media exposure+1), international presence and ROA. The variable country effect cannot be added because it is a time-invariant variable, so it is not going to be considered in the fixed effects model asthis considers only the variations within a company across time.

In order to run the Hausman test, a regression needed to be run with the fixed effects model and the result stored. Then, the same process using the random effects model regression had to be carried out. Finally, the Hausman test could be performed, as shown in the table below. Table 1: Hausman test

The result from the Hausman test is a p-value that is small enough (<5%) to reject H0, so the correct model to use for this first equation is the fixed effects model. Reported here are the two regressions that were run:

1. Fixed effects model

RVi,t = α + β1lnREi,t + β2lnMEi,t + β3IPi,t + β4ROAi,t + Ɛ

2. Between effects model

RVi = α + β1lnREi + β2MPi + β3IPi + β4lnAGEi + β5ROAi + β6CEi + Ɛ

Where, for a company i:

• RV: reporting value

• α: intercept

• βk: coefficients of the independent variables

• lnRE: natural logarithm of the revenues

Prob>chi2 = 0.0002

= 21.68

chi2(4) = (b-B)'[(V_b-V_B)^(-1)](b-B)

Test: Ho: difference in coefficients not systematic

B = inconsistent under Ha, efficient under Ho; obtained from xtreg

b = consistent under Ho and Ha; obtained from xtreg

ROA -.0569237 -.0318859 -.0250378 .021661

IP .215561 .2616374 -.0460764 .0785299

lnME 3.356998 2.146747 1.210251 .666336

lnRE 8.960163 6.087302 2.872861 1.197694

fixed random Difference S.E.

(b) (B) (b-B) sqrt(diag(V_b-V_B))

Coefficients

17 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

• lnME: natural logarithm of the media exposure

• IP: international presence

• ROA: return on assets

• lMP: media pressure

• AGE: age of the company

• CE: country effect

• Ɛ: error term Media pressure was used only in the inter-firm analysis because, for many companies, it has the

value of zero many years, rendering them comparable to a constant. For this reason it was not possible to analyze in a fixed effect model.

3. Results Descriptive analysis

Figure 2: Reporting value

The graph reports the line plots of every company for the 2006-2015 period. It appears immediately clear that, in the majority of the panels, the reporting value has a growing trend. This result is in line with expectations: society’s expectations about corporate disclosure is increasing year on year, along with guidelines that help companies report information in a more standardized way. Consumers, investors, employees, regulators, suppliers, and so on, are ever more interested in CSR, and the result has been the growing incidence and sophistication of corporate social reporting (Gray et al. , 1995). Moreover, as has been said before, communication is the main tool companies have in order to gain, maintain and repair legitimacy.

05

01

00

05

01

00

05

01

00

05

01

00

05

01

00

05

01

00

2005 2010 2015 2005 2010 2015

2005 2010 2015 2005 2010 2015 2005 2010 2015 2005 2010 2015 2005 2010 2015

Abercrombie & Fitch Adidas Aksa Akrilik Asics Asos Plc Burberry Coats

Columbia Sportswear Edcon Fast Retailing Foot Locker Foschini GIII Apparel Gap

Gildan Guess H&M Hermès High Fashion Group Hugo Boss Inditex

JD Sports Kappahl Kate Spade Kewal Kiran Li Ning Lojas Renner Louis Vuitton

Marimekko Next Plc Nike Odd Molly Puma Ralph Lauren Ross Stores

Shenzou International Suominen Truworths Under Armour VF Corp

RV

Co

mp

an

ies

Time

Graphs by A

Reporting value

18 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Table 2: Descriptive statistics

In table 2, we can find the principal statistics of the variables chosen for this model. Each variable has 400 observations, as there are no missing values. CSR disclosure has a minimum value of zero and a maximum of 102. 5. The mean is 40 (approximation of the value reported in the table), and is well below the total possible score of 206. The maximum too, which has a value of 102. 5, is nearly half of the total value, summing the maximum of each indicator. Although the way we built the index may be a reason for this, such low values also mean that companies still do not disclose all the information about their activities. Some of them may lack instruments to measure environmental and social performance, meaning that they are unable to provide quantitative data about these issues. Several studies highlight how companies are used to reporting good news while omitting bad news; typical behavior in the sphere of greenwashing (Delmas and Burbano, 2011; Berrone et al. , 2015).

This is one reason corporations may decide to disclose all the information about the environmental and social issues where they perform well while choosing not to report problematic issues, in order to avoid possible criticism from stakeholders. The voluntary nature of the sustainability report, and a lack of universally adhered to guidelines may increase this behavior.

Observing the other statistics, on the one hand there is a good news with only 1% of the reports having a reporting value that scores less than 10 points; these are likely to be the financial statements. However, on the other hand, 99% of the analysed reports show a score that is less than 95. 5. The distribution of the reporting values has a positive skewness and it is a leptokurtic distribution, which has a higher peak than the normal distribution.

The variable revenue has a great dispersion as it is possible to notice from the value of the variance, and the difference between its minimum of $7,388 million and the maximum of $40. 64 billion is very large. For these reasons, its natural logarithm was taken when we ran the regression. 50% of the observed revenues is less than $2. 178 billion, while the other 50% is more than $2. 178 billion. The distribution of the revenues has a clear skewness on the right and it is leptokurtic.

On average, the companies have 70 years of activity, with a minimum of 4 years and a maximum of 260 years. The variance of this variable, and the difference between its minimum and maximum value, is quite large too, making it reasonable to take its natural logarithm. The majority of the companies can be considered relatively young: 50% of them are less than 58 years old. This is likely to be a peculiarity of the apparel and textile sector, with companies that cease their activities and others that decide to enter the sector each year, due to lower entry and exit barriers than in other sectors, such as oil and gas.

The variable media exposure has a minimum value of 0, which is common for some companies in many years, and a maximum value of 827 articles in a year. In 50% of cases, companies are reported

kurtosis 2.368336 8.647749 5.530579 9.990827 1.720069 19.08693 6.18414 3.289596

skewness .6383767 2.274256 1.511478 2.494965 .2786121 3.786154 .0203854 -1.125535

variance 548.7204 5.01e+07 2659.348 20953.46 1046.095 6.046892 93.02406 230.9373

max 102.5 40640 260 827 99 18 55.32 62

iqr 37 4742.2 57.5 108.5 61 0 10.6097 12

p99 95.5 34500 256.5 708 98 13.5 34.4049 62

p75 56 5705 90.5 111.5 67.5 0 16.7269 54

p50 35 2178 57.5 28.5 36 0 10.98575 47

p25 19 962.8 33 3 6.5 0 6.1172 42

p1 10 29.194 6.5 0 0 0 -14.9136 7

mean 39.69875 5155.205 69.225 91.96 40.3 .885 11.17274 43.8

min 0 7.388 4 0 0 0 -31.4488 7

N 400 400 400 400 400 400 400 400

stats RV RE AGE ME IP MP ROA CE

19 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

fewer than 29 times in a year while, in the other 50%, it is more than this. It is a low value, which may reflect disinterest that media have with respect to some companies in this sector. This may be due to some firmsbeing relatively new with only a few years of activity, meaning they are likely to be unknown to the general public; some of the companies in the sample are not multinational, therefore attracting the interest only of some local or regional newspapers, not national or international ones; finally, the apparel and textile sector has a lower environmental impact than others. The distribution of media exposure has a clear positive asymmetry and a kurtosis that has a higher peak than a normal distribution.

As the variable has quite a big variance, it was decided to take the logarithm of it; however, as some values were equal to zero, the following transformation was made: ln(ME+1).

Regarding the variable international presence, there are companies which, for a few years, operated only in the domestic market, from here the minimum value of 0%; others sell nearly all their products (99%) internationally. On average, the international presence of the companies is equal to 40%, meaning that nearly half of the sales are made outside the country of origin. This is quite a high value that reflects the needs in a sector like apparel and textile, one of entering new markets and outsourcing production to less developed countries. The distribution of the variable presents a slight right-asymmetry and it is leptokurtic, although less accentuated than for the other variables.

For media pressure,the number of articles that were found each year ranged from a minimum of zero to a maximum of 18. The minimum value is not surprising, being in line with the value of the variable mediaexposure. However, conversely to this variable, media pressure reflects only negative visibility, thus making the possibility of finding some articles even harder. On average, companies are the target of negative articles just once a year and, in 50% of the observations, companies did not experience any form of media pressure, as defined before. For these reasons, the dispersion of the values is very low compared to the other variables and is reflected in the value that the variance has, which is equal to 6. 05. In the same way, the distribution of the variable is clearly leptokurtic with fat tails and concentration of the values around the mean.

Finally, we have the two control variables. The return on assets, expressed as a percentage, ranges from -31. 45% to 55. 32%. On the one hand, such a negative minimum value signifies that the company is investing heavily while receiving little income, so it may have no money for CSR programs. On the other hand, the maximum ROA value is quite high, meaning that the company is highly profitable compared with the total assets it owns. On average, the return on assets of our sample companies is equal to 11. 17%, while, in 50% of cases, it is lower than 11% and in the other 50% it is higher than 11%. The distribution of the ROA values is almost symmetrical and has higher peak than a normal one.

The last variable attempts to capture the possible effects that a company’s country of origin may have on its way of disclosing information.

The minimum score is 7, which was given to companies from China, while the maximum of 62 was assigned to Swedish firms. The distribution presents negative skewness, meaning that the majority of the companies come from countries that score high in the ranking, while only a few companies hail from poor CSR performing countries. Main Results

A fixed effects model and then a between effects model were run in order to test for the previously-developed hypotheses.

However, before doing this we performed diagnostic tests. First of all, for the fixed effects model, we had to test if there was a problem of heteroscedasticity. To do that we ran a Modified Wald test, which suggested to us that our data sufferedfrom heteroskedasticity and that we wouldneed to undertake a corrective measure, such as robust standard errors. Other tests, such as the Breusch Pagan LM Test of independence and the Pasaran CD Test for cross-sectional dependence, are much more an issue for macro-panels in long time-series (20-30 years) so there wasno need to perform them (Torres-Reyna, 2007).

20 European Journal of Economics, Finance and Administrative Sciences Issue 93 (2017)

Table 4 reports the results from regressing the independent variables (revenues, media exposure, international presence and return on assets) on the dependent variable (CSR disclosure) after having corrected for heteroscedasticity using robust standard errors. Table 3: Results of the fixed effects regression

The F value for the model is significant at the 0. 01 level. This means that the independent variables, taken together, have an influence on the level of CSR disclosure. However, only size and media exposure are significant, while international presence and return on assets are not.

In the table above there are three R-squared reported, however we are interested only in the within one, which has a value of 18. 95%. This means that size, media exposure, international presence and return on assets jointly explain the 18. 95% of the CSR disclosure within companies over time. The correlation between the errors and the regressors is obviously different from zero, as we are in a fixed effects model, which assume that errors and independent variables are correlated. Rho term is equal to 0. 76. This means that 76% of the variance is due to differences across panels.

We can now analyze the β coefficients for the statistically-significant variables revenue and media exposure. Both are positives, implying a positive correlation between these two independent variables and CSR disclosure. This means that when media exposure and revenues increase, from one year to another, CSR disclosure will increase too. Precisely, if we increase revenues by 1%, reporting value will increase of 0. 08 points and if media exposure increases from one year to another by 1%, the score of CSR disclosure will augment by 0. 03 points.

Table 5 shows the results from the betweeneffects regression, which estimates using the cross-sectional information in the data:

rho .75701174 (fraction of variance due to u_i)

sigma_e 11.744824

sigma_u 20.73028

_cons -46.9536 20.54681 -2.29 0.028 -88.51345 -5.393759

ROA -.0569237 .1276049 -0.45 0.658 -.315029 .2011816

IP .215561 .1617561 1.33 0.190 -.1116217 .5427437

lnME 3.356998 1.482314 2.26 0.029 .3587358 6.35526

lnRE 8.960163 2.847856 3.15 0.003 3.19983 14.7205

RV Coef. Std. Err. t P>|t| [95% Conf. Interval]

Robust

(Std. Err. adjusted for 40 clusters in company)

corr(u_i, Xb) = -0.5369 Prob > F = 0.0001

F(4,39) = 7.99

overall = 0.2309 max = 10

between = 0.2655 avg = 10.0

R-sq: within = 0.1895 Obs per group: min = 10

Group variable: company Number of groups = 40

Fixed-effects (within) regression Number of obs = 400