Córdoban Discoursesjamesshields.blogs.bucknell.edu/files/2012/12/Cordoba-final.pdf · (Prov. 1:5)....

Transcript of Córdoban Discoursesjamesshields.blogs.bucknell.edu/files/2012/12/Cordoba-final.pdf · (Prov. 1:5)....

ARC, The Journal of the Faculty of Religious Studies, McGill, 27, 1999, 137–159

Córdoban Discourses: A Drama of Interreligious Dialogue* James Mark Shields Faculty of Religious Studies, McGill University

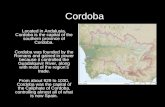

SETTING: Córdoba, Spain, 1135 CE, 29th year of the reign of ‘Ali “amir al-muslimin,” second king of the Berber Almoravid dynasty, rulers of Moorish Spain from 1071 to 1147. Córdoba, the capital of Andalus and the center of the Almoravid holdings in Spain, is a bus-tling cosmopolitan center, a crossroads for Europe and the Middle East, and the meeting-point of three religious traditions. Most signifi-cantly, Córdoba at this time is the hub of European intellectual activ-ity. From the square—itself impressively large and surrounded by a massive collonade, the regularity and ordered beauty of which typifies the Moorish taste for symmetry (so beloved of M.C. Escher)—can be seen the huge Córdoban mosque, erected in the 8th-century by Khalif Abd-er-Rahman I to the glory of Allah, oft forgiving, most merciful. It is the second largest building in Islam, and the bastion of the still en-trenched but soon to fade Muslim presence in western Europe. SCENE: Three figures sit upon stone benches beneath the westernmost colonnade of the Córdoban mosque, involved in an animated, though friendly discussion on matters of faith and reason, knowledge and God, language and logic. The host is none other than Jehudah Halevi,1 and his esteemed guests Master Peter Abelard2 and the venerable Råmånuja,3 whose obviously advanced age belies his youthful voice, gleaming eye, quick hands, and general exuberance. It is autumn, early evening…

* The following text reproduces, to the best of his ability, a recent dream of the author, after an evening of overstrenuous persual of sundry medieval texts. It should be noted that any historical or factual errors are entirely the fault of the limitations of retrieval, and in no way reflect upon the veracity of the char-acters or the truth of the dream itself.

138 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

Jehudah: Once again, I cannot sufficiently express my sincere pleasure in having two such esteemed guests. Master Abelardus, your taking some time from your busy schedule is much appreciated… Abelard: But my dear ben-Samuel, you must know that my affairs are in a disordered state, as per the usual.4 My persecutors are relentless, and now I hear that the famed Bernard of Clairvaux has shown interest in defaming me to the Christian world. At any rate, the opportunity to discourse with you again would alone be enough to tear me away from the pesterings of Lombardus5 and that damnable Brescia,6 let alone the rare chance to hold forth with the venerable Master Råmånuja; to drink, if you will, a rare draught from the timeless fount of Indian knowledge and teaching. Jehudah: Young Lombardus no doubt looks upon you as something of a hero, as I am sure do many of the hot-blooded youths of Paris… Abelard: That wretched affair7 has caused such distraction; I’m sure that even in the most remote hills of India the story of my misfortunes abounds. I wish to speak of it no more. I am sure Råmånuja, whose own ascetic practice, though freely chosen, unlike my own, was precipi-tated by the ways of the fairer sex,8 will oblige. But let us continue our discussion, as pleasant as such digressions can be on such a beautiful autumn eve. I was asking our resident Brahmanist here to explain, if he may, his so-called viçi‚†ådvaita; to explicate, in particular, his “qualified non-dualism” vis-à-vis the teachings of his estimable predecessor Çaπkaråcårya. As our (Jehudah and my) Proverbs say: “A wise man by hearing will be wiser, an intelligent man will gain sound guidance” (Prov. 1:5). Råmånuja: Thank you, Master Abelard, for your kind words, and you dear Ha-Levi, for your hospitality, and the opportunity to speak on divers matters in this great city of learning. My regret, if any, is that we lack a Mohammedan participant in our colloquy. Jehudah: Yes, there are certainly Muslim (as they prefer to be called) scholars abounding here (though none, perhaps, of equal to the late Ibn S⁄nå9); unfortunately none have been able to make it here this evening, it being Rama∂ån. Perhaps at a later date we will be obliged as such. But there is young Roshd [gestures towards a young boy reading on a bench nearby]. Though but a boy of nine, he is said to be quite an adept in such matters as we have been speaking.10 I shall call him over.

James Mark Shields ❖ 139

Unity in D(e)i(vers)ity Råmånuja: But as to your enquiry, Peter. We “objectors” (p¨rvapak‚ins) to the advaitan philosophy of Çr⁄ Çaπkara cannot fully accept the idea of an eternal, absolutely non-changing consciousness—whose nature is pure non-differenced intelligence, free from all distinc-tion whatever—as the Braham, the Supreme Lord, similar perhaps to your own European image of God, particularly, as I understand it, coming out of the Greek tradition. For just as your God of Abraham maintains contact with the world, so for us viçi‚†ådvaitin the reality of immanence involves the manifestation of Brahman, the ensoulment, if you will, of the world and of individual souls by Brahman. This is the basis for our core concern with the reality of “plurality” and difference, based on linguistic evidence and empirical knowledge (Vedånta I.i.1). Abelard: So that your Brahman partakes in “contingency”? Råmånuja: For Çaπkara, the One is nirgu~a, that is, without qualities or attributes; its seeming manifestations in the world are in fact illu-sory. We objectors dispute this vision of the Supreme, for such a qual-ity-less God is unthinkable, as is anything “attribute-less.” Besides, is it not the relation of Brahman to j⁄vas (souls) and prak®titi (materiality) which reveals the Glory and all-pervading aspects of the One? The disciples of Çaπkara, as I am sure happens in your own faiths,11 have moved away, we feel, from devotion, or bhakti, to a too-limited focus on theoretical knowledge and cognition, as if these, without grace, could bring salvation. Jehudah: But of plurality? You were about to say… Råmånuja: Yes, forgive me. We do not believe in a “pure conscious-ness.” Consciousness must be of something, after all; this seems too obvious a point to belabour. Many arguments have I propounded, in my commentaries, to show that though Brahman is the source and cause of all things, this need not entail non-differentiation. Suchwise is our belief more aptly known as the “non-dualism of the qualified.” What are qualified are One, what qualifies is Many. When the Upani‚ads, to which as Uttaravedånta we attach great importance (be-ing, in some ways, our New Testament…forgive me Master Halevi, our “Second Testament”); as I say when the Upani‚ads identify Brahman and the world, they denote not non-differentiation but rather “insepa-rability,” what in my language we call ap®thaksiddhi. In other words,

140 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

though Brahman is of course the All, the One—in relation to the souls (cit) and the world (acit); as Sagu~a-Brahman, or Îçvara—Brahman’s unity is filled with diversity. As the Supreme Lord Brahman has six qualities: jñåna (knowledge); bala (strength); aiçvarya (sovereignty); v⁄rya (heroism); çakti (power); and tejas (splendour). Young Averroës: Thus, if I understand you, a tripartite division of the cosmos, something akin perhaps to the Christians’ heretical tritheism? Råmånuja: [laughs] Well, no, not precisely, though I should defer to Master Peter for a response to that remark. Remember that, although we assign eternality to “God,” the selves and the world, they are not on the same footing, the latter two being necessarily dependent upon the former; the j⁄vas and the world make up the body of Brahman, who, like your own Allah, is all-powerful. Abelard: Young Roshd and I will discuss my heresies later; God knows, he is not the first, nor probably is he the last to accuse me of such… Would you say, Råmånuja, that your doctrine could be put thus: Reality is not some sort of synthesis, nor is it illusion, but rather is exhausted by but does not exhaust Brahman? Råmånuja: Very good, yes. In the case of the blue lotus, for example, the attribute of “blueness” is, you must admit, distinct in some fashion, from the substance “lotus”—distinct but yet inseparable. In fact the “blueness” of the lotus depends upon the “lotus” for existence, though not vice versa. Abelard: Indeed. Brahman qualified by the universe and j⁄vas is One. Råmånuja: Yes. The universe, the plurality of souls are distinct but inseparable from Brahman. Abelard: I have suggested, in my ill-used treatise on the Christian Trinity,12 that, by way of analogy, the Godhead is similar to a piece of brass, from which is self-begotten the seal, from which proceeds the act of sealing. Thus, in Christian terms: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. But of course, in my recognition of the plurality of religious faiths,13 I have suggested ulterior “names” for these aspects of divinity: Power, Wis-dom and Love.14

James Mark Shields ❖ 141

Jehudah: This is interesting to me. But I have an objection to make: it seems to me that either, on the one and, this diversity of persons must consist in the names only, and not in actuality, so that only the names are different, and there is no real diversity in God Himself. Either this must be the case, or else the diverity is in actuality (in re, as you may say in your Latin tongue) and not in names. Or, failing this supposi-tion, then it must be both in actuality and also in the names. If it were possible, however, for one of the names to be taken away the total meaning of the Trinity would be lost and, if we consider the names only, there is no eternal Trinity or persons to whom names can be given by men (see Theo. 1237A). Young Averroës: Assuredly Halevi is right; and, moreover, how can there be three persons where it is evident that there are not three things? Why, indeed, speak of “three” in such a case? There is not even a multiplicity. How can a thing be multiple if it has no multiple within it? There must be parts to make any kind of multiplicity. Yet you have said that there are no parts in your so-called Trinity. Abelard: Perhaps… Young Averroës: Wait, let me finish sir, if you please. Since God is substance and this name God refers to substance, not to a person, we may just as well speak of a threefold God or a threefold substance or, for that matter, of a threefold Father (all praise to Allah!). For what does a threefold God or threefold substance mean but three Gods or three substances? Indeed ye have put forth a thing most monstrous!15 Abelard: Well indeed, a Muslim scholar we do have with us! Perhaps I will let my colleague Råmånuja answer this one, for, though it pertains to my vision of the Trinity, it also puts into question the unity-in-diversity of which you have spoken. For the central problem here, it seems to me, is that we have no adequate philosophical forms of thought to clarify this idea, which seems to confound reason, and per-haps even faith, faith in a Supreme Lord (cf. Theo. 1241B). As such, the wisdom of India may help us to come through this muddle and into a clearer light… Råmånuja: Very well, let me see. Perhaps I should relate my interpre-tation of the famous Upani‚adic statement Tat tvam asi, or “Thou art that!” (Ch. VI.12–14) For Çaπkara this merely restates the Unity of Brahman, it functions thus as a tautology of sorts; but we view it quite

142 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

differently. From another text which reads “Having entered with this individual self, let me proliferate name and form,” (Ch. Up. VI.II.3) we learn that, since the ensouling self is ensouled by Brahman, Brahman is referred to by the names of the ensouling self. Thus it is Brahman who is expressed by the two words “that” and “you,” applied in a way that might be called “correlative predication”—the word “that” declares him who is the cause of the world, the source of every noble quality, with-out change, while “thou” declares that very Brahman qualified by the mode that is one’s body insofar as Brahman is the inner Controller of the individual self. In short, one can say that the two words “that” and “thou” are applied to one and the same Brahman in respect of a differ-ence of grounds in him for the application. Perhaps I should sum up this way: from the viewpoint of the qualifying mode (mode-possessor relationship) identity-in-difference can be proclaimed; while from the causal-Brahman-effected-Brahman point of view, identity-in-difference is stressed (see Lipner 1986, 46–47). God is the sole Immanent ground of Reality of all this evolved and evolving world, pervading all that is concretely Real down to the blade of grass; the effulgence that illumi-nates the universe (Vedånta 6). Içåvåsyaam idaµ sarvam (“By the Lord is all pervaded”; Isa Up. 8). Jehudah: We must be wary, all of us, of pantheism. I must object to the temptation, particularly prevalent among philosophers of our age, to place Nature on a par with God… (Kuz. I.76) Råmånuja: “Ah, now: While His is the Essence, He ‘essentializes’ and develops.”16 That is, we must remember that Brahman is not exhausted by the universe and souls, though He exhausts them. Says our Isa Upani‚ad: “Into deep darkness fall those who follow the immanent. Into deeper darkness fall those who follow the transcendent” (Isa Up. 9). Not pantheism, surely, though perhaps “panentheism”—God is all, and is in all, while not being exhausted by all (see Hartshorne 1987). Abelard: And to think that I once thought of myself, in my pride, as the only philosopher in the world! (Story 65)

James Mark Shields ❖ 143

Tertium Via: Conceptualism Abelard: Some sort of tertium quid, or tertium via, is here presented I think, staying the balance between the pitfalls of what we in the West-ern tradition might call “idealism” (or Platonism, rationalism), which loses sight of the magnificence of God’s creation, and the glory of eve-ryday human existence, and “nominalism” (or Aristotelianism, empiri-cism), which, in sticking too closely to empirical reality, comes in dan-ger of losing God and the spiritual realm altogether.17 If so, then we really have crossed a Rubicon in our thinking, before even meeting; for I have been working on what can be called “conceptualism,” a linguis-tically-based epistemological framework in which to reconcile the du-alities we are facing, not just in terms of God and the world, but in everyday language, with respect to identity, differentiation, universal-ism and pluralism. In such, “universals” are neither “realities” in the traditional sense, nor mere names, but the concepts formed by the intellect when abstracting the similarities between perceived and indi-vidual things; while not “real” in and of themselves, they have a lin-guistic and intellectual reality that derives their participation in particu-lars. Thus we know the universal only through the particular instantiation of such, and we perceive the particular in the universal. In short, the universal is considered to be the one characteristic which enters into particular things and through which they are known. The variety of things bespeaks differing degrees of particularity, it is a mat-ter of differing forms of the universal. The logic of the Platonists (and perhaps the advaitins), only succeeds in showing how there can be di-versity understood by the mind, it goes nowhere towards revealing how there can be particular things in the world as perceived. For the act of thought and the process of perceiving must be distinguished from their objects (see McCallum 1948, 41–42). Råmånuja: Yes! For neither “mere Being” nor “consciousness” alone constitutes reality; there is a distinction between consciousness and its objects, which rests on the relation of “object” and “that for which the object is”; Being and consciousness are not one (Vedånta I.i.1). In an-swer to the earlier remark made about “substances,” let me suggest that “substance” be conceived as “that which has a mode,” a subject-in-relation, perhaps, a “that” which involves, necessitates even, a “thou,” in order to fulfill its “thatness.” Let me explain in terms familiar to Indian thought, before I make more general statements, and allow Master Abelard to respond, as well as you Master Halevi, who have been silent, but who I know has much to add here. There are six sub-

144 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

stances in viçi‚†ådvaita, but three eternalities, which are Brahman (here I will say “God,” to ease communication, though wary of the differ-ences) and God’s body, as j⁄vas (souls) and prak®ti (nature, the world). Like the individual soul, God is the essence of intelligence, self-revealing, and knows objects through dharma-bh¨ta-jñåna; but God is free from all defects and is possessed of all auspicious qualities. God is also all-merciful, young Master Roshd, and salvation only comes through his grace, complete submission (’islam) to which we call in our language prapatti. God is both material and efficient cause of the uni-verse: as cause, he has as his body the souls and matter in their un-manifest form; as effect, he has them in their manifest and diversified form. Prak®ti, the physical world, evolves in its infinite variety under the guidance of God. The material cause is not the “substance” as such (“clay”), but as characterized by a mode (“lump”), and the effect is the same substance as characterized by another mode (“pot”). In short, what are “qualities” in other systems are “modalities” in viçi‚†ådvaita. In terms of causation, reality is the cause; reality in different modes is the effect. All change is modal change. Abelard: The religion of the Christian faith asserts and believes in one God as three Persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. One God, not a plurality of Gods: one Creator of things visible and invisible, one first principle, one goodness, one disposer and Lord of all things; one eter-nal, one omnipotent, one immeasurable; and withal affirms a single identity of unity…except, and this is the key to my stance, except as per-tains to the (necessarily) discrete attributes of the three persons. Plural-ity, multiplicity, diversity are professed only in regard to the persons. In everything else unity is maintained (Theo. 1229B, C). Jehudah: You sound as though you are back as Soissons, good Peter; you need not apologize for the admission of diversity; we all seek to learn here, not to judge.18 But now I shall put in my own word; as you say, I have been quiet, letting these thoughts be spoken, so that I could formulate my own perspective more thoroughly. In my view, the at-tributes, or names given to God, are many, although His essence, as you say, is only one. The variety arises from the variety of places where God’s essence dwells, just as the rays of the Sun are many whilst the Sun is everywhere the same. Our human sense, after all, can only per-ceive the attributes of things, not the substrata themselves. It is not these to which we must render homage. One sees a prince, for instance, in war in one habit, in his city in another, in his house in a third—all different modes or states of being, yet one can see, following one’s

James Mark Shields ❖ 145

judgement rather than one’s perception, that he is a prince at all times! With respect to the Great Prince, though his appearance, manner, dis-position and qualities may change, still we consider him to be the same and the Prince, or King, or Lord, because he has spoken to thee and given thee his commands (Kuz. IV.3). Theologia: Language, Speech, Scripture Råmånuja: I am glad you have spoken thus, dear Jehudah, for you bring in the linguistic element which I think serves as a bridge of sorts between the doctrines we are all propounding here, whatever may be our theological differences. For it is speech (çabda) which proves differ-ence. Speech possesses the power of denoting only such things as are affected with difference. For the plurality of words is based on a plural-ity of meanings; the sentence, therefore, which is an aggregate of words, expresses some special combination of things (meanings of words), and hence has no power to denote a thing devoid of all differ-ence (Vedånta I.i.1). All terms whatsoever denote Brahman insofar as distinguished by the different things which we associate with those terms on the basis of everyday speech and etymology. But there is even more to language than this. Vedic language, all language actually, is, pace the Prabhåkara position, “fact-assertive,” but this need not deny the prescriptive element that you, Halevi, have just exposed. Vedic words have an innate denotative power demanding fruition in the ul-timate production of real things, but they do not “terminate” in natu-ral objects, which are only, one might say, a “first order stopping-place.” The çruti terminate referentially in Brahman, the very ground of all Being. In an exegetical analysis of the mystical syllable OM (found in the Çvetåçvatara Upani‚ad), I have tried to develop the structural correspondence between language and reality (see Lipner 1986, 21–22). Language is not an entity apart from the Supreme. Jehudah: In my writings have I also pursued this line, in keeping with a long tradition within Judaism, particularly the Kabbalistic tradition, which, as you may know, places much emphasis on the close tie, or even the coevality of God and the divine language (in the Tetragram-maton)—the voice of the words of the living God which produced the form of the things spoken. YHWH speaks, and things come into exis-tence. Abelard: Yes, Jehudah, and we have had occasion to speak of this be-fore. I want to return, however, to several points in the long and in-

146 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

formative discourse just given to us by our viçi‚†ådvaitin friend. First, with regard to your comment on the modality of change, I would like to note that, in so-called “modal” propositions, normal (predicate) logic does not apply; normal logical analysis is shut down.19 Modals hearken to a logic which is something more than the predicate logic we have come to assume as the only form of logic; perhaps, with modals, we are driven to re-examine the linguistic element of logic, the “word” of logos. In my work I have sought to rigorously apply the rules of logic to all fields of thought; but I do not of course attempt to apply the rather limited formal logic of which we are familiar; for I am con-cerned, largely, with how we express concepts and words and how we understand or give meaning. Now, I would like to ask our guest to ex-plain, if he might, the “correlative predication” to which he referred; I am afraid I am somewhat unclear on this. Råmånuja: Certainly, Peter. I have used the rather awkward term “correlative” or “co-ordinate predication” to translate the Sanskrit’s samånådhikara~ya. In a co-ordinate predication the identical import of terms taken in their natural signification should be brought out. This fits, I think, with the modal logic we have been speaking of. Patañjali’s Mahåbhåçya defines co-ordinate predication as “the signification of an identical entity by several terms which are applied to that entity on different grounds” (see Adidevananda 1968). Abelard: In other words, accidental or adjectival predication does not imply separate identity. I may say that a man is a good lute player; I do not therefore say that he is a good man (Theo. 1263B). Råmånuja: Exactly. This is in accordance with the general principle that co-ordination is meant to express one thing subsisting in a twofold form.20 Thus Identity-in-Difference: in such a proposition the attrib-utes not only should be distinct from each other but also different from the substance, though inseparable from it. Co-ordinate predication im-plies differentiation not only between individual objects but also within the object. Çar⁄ra-çar⁄ri-bhava: thus in Brahman as in the purple lotus… Jehudah: Blue. Blue lotus, my friend. Råmånuja: Yes, of course, blue lotus, forgive me. Jehudah: No apologies needed; I thought to call on you there as a joke of sorts, for I am in such agreement with you that, in order for this to

James Mark Shields ❖ 147

be a true disputation, I thought… But I was going to point out, in our flirting with questions of language and speech, my impression and opinion that it is speech—oral communication—which must be given priority over the written word. Written texts can certainly prompt and give knowledge, but true devotion is a conversational activity, a listen-ing and speaking. In more general terms, it is the faculty of speech which transmits the idea of the speaker into the soul of the hearer; as the Proverb says (not “reads,” for it is a living word—in God, S’far, divine calculation, Sippur, and writing, Sefer, are a unity)21: “From the mouths of scholars, but not from the mouths of books” (Kuz. II.72). Experience, assuredly, must be the starting point for thought.22 Abelard: I agree. I have used, as a term denoting this “logic above logic,” this “speech above speech,” this “over-knowledge”—the ancient word theologia.23 Religion and philosophy have the same fundamental purpose: an understanding of life and reality. Theology subsumes these, drawing them into concert; it involves not only logic, in the fullest sense, but also physic and metaphysic, and for myself is cen-tered around a critical approach to the meaning of words and concepts as the basis of knowing—this being a bridge of sorts to further our “understanding” of divinity and the world. For to get understanding we should employ every available means.24 Råmånuja: Right. “Unitil divya-sthåna25 over land flees, our ‘theology’ topples opponents.”26 I as well believe that texts other than our Vedas should be used in our studies and our devotion: hymns of the saints, Purå~as, Tamil literature, Agana literature—all these can be helpful and illuminatory, as addendum to the çruti and sm®ti. Young Averroës: But what does all this presage in terms of your re-spective readings of the Divine Word—Holy Scripture? Abelard: Good question, Roshd. My Sic et Non is a work of disputatio—a tool for the sharpening of the wits rather than a systematic exposi-tion of nature or God. “Contradiction” within scriptural passages are neither to be glossed over, denied, nor admitted as “contradictions” which refute the corpus in toto. Rather, these must be set forth, in or-der that we may see the modes and relations involved, so that we may approach the texts with a more wary eye and an ear for nuance and subtlety. For, bearing in mind our foolishness we believe that our spontaneous understanding is defective, not the divine record; but our achievement of full understanding is impeded especially by unusual

148 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

modes of expression and by different significances that can be attached to one and the same word, as a word is used now in one sense, now in another (Sic et Non, quoted in Tierney 1983, 173). Råmånuja: Aha! Scripture is, in a strong sense, not derivative but originative—it is not a mere statement (anuvåda) bout something “other.” Scripture speaks, shows divinity (Vedånta I.i.1). But in advaita, the empirical evacuation of terms to the point of signifying absolute non-differentiation destroys the very fabric of language as we know it and by implication nullifies the very raison d’être of the Scripture (Lip-ner 1986, 28). I have conceived of a method of grasping seemingly contradictory scriptural passages by pointing to the different empha-ses, or the different grounds upon which these attributes are applied. These are, briefly: (1) analytical texts—which declare difference be-tween world, self, and Brahman by virtue of “world” in this case being the non-sentient matter which is the object of experience; (2) mediating texts—in which Brahman is the inner self of all entities that constitute His body, and where j⁄vas and prak®ti are particular modes of Brahman; (3) synthetic texts—such as the Tattvamasi, where the unity of Brahman, in causal and affected aspect, is maintained, and where souls and mat-ter are nothing more than modes of Brahman; here is the aspect of dependent existence, and the transcendence of Brahman, stressed. Jehudah: It is remarkable, Råmånuja, but I too, in my Kuzari, have put forth a tripartite schema for dealing with attribution in terms of names for God, which resembles yours: (1) relative attributes (such as “blessed, praised, holy”)—which distinguish God, borrowed as their are from the devotional stance; but which, though numerous, do not con-note a full plurality or absolute transcendence, they do not affect his Unity; (2) creative attributes—which are derived from acts emanating from Him by ways of the natural medium, thus names of God which are expressed in recognition of his eternally creative and life-giving capacity; (3) negative attributes—attributes which are given not as true names but rather to negate the possibility of their contraries being attributes of God; ultimately, of course, God is above these referents… Råmånuja: Indeed! I have suggested that those (Vedic) texts which deny “plurality,” actually deny that plurality-which-contradicts-the-Unity of Brahman, who has no competitors (Vedånta I.i.1). These do not, however, deny that plurality on Brahman’s part which depends on its intention to become manifold—a plurality proved by the text “May I be many, may I grow forth” (Ch. Up. V.3.3). For “Immanence” is not

James Mark Shields ❖ 149

the “non-transcendent” or “finite,” but is the presence of the infinite in the finite—establishing the latter in existence and continually imparting to it the power to be (Rhagavachar 1972). Jehudah: In the last instance, “One” is used to negate plurality, in the sense of there being ulterior or separate essences, but does not thereby imply Unity as usually conceived, for instance, by the advaitins or our own Neoplatonists, at times—a “Godhead” which is All, but without qualities. Abelard: We are reaching a consensus, it seems, with regard to the importance of language, beyond the merely “grammatical” or “syntac-tic-semantic” realm; language and language-use have ontological impli-cations, and thus, it would seem, implications on divinity. Bhakti: Devotion, Atonement, Liberation Jehudah: Yes, good Peter. But let us be wary; as we before strayed close to pantheism, let us not emphasize rhetoric over all else, and allow the cadres of dialecticians who populate our respective realms to claim us as ones of their own; let us not become “sophists,” like the Mutukul-liman.27 For,

Wisdom is withered that abode in state In hearts exceeding wise For all they thought and did devise Is other than he knoweth…28

Råmånuja: Quite right! For all my attempts to bring the utterly tran-scendent Brahman of the advaitins “down to earth,” I do so not to hu-manize God so much as to render more proper our submission and devotion to his word. For, as my great teacher Çr⁄ Yamunåcårya taught, after the twofold training of the mind in karma-yoga (performance of those duties fit to one’s station in life, selflessly, ni‚kåmyakarmayoga, as per the G⁄ta), and jñåna-yoga (meditation upon the self as distinct from body, mind, from which comes “self-knowledge”), bhakti-yoga is the third and ultimate stage. But first, let me add, “self-knowledge” here is nothing other than the realization of one’s dependence on Brahman. As one disassociates one’s “self” from the world or “nature,” one sees one’s association yet distinction from “God.” Against Çaπkara, the crypto-Buddhist, dissolution of Self into Brahman is not “liberation,” but rather an understanding of true Self (åtman). Thus, it is a destruc-

150 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

tion not of the ego so much as of egoity—and thus presages a new atti-tude or disposition towards works and faith. As it has bee said: “Lest ultimate truths hie Endymion’s route,29 may atman reveal the I-Nåråyå~a”—the Brahman-filled and Brahman-dependent Self.30 As to bhakti, it is the pinnacle of the life process, though not the “end,” for it is a stage lasting the rest of one’s life. Bhakti we p¨rvapak‚ins use in a rather distinctive way; it does not connote the popular sense in which it is understood. When the meditation of jñåna attains the form of what might be called “firm remembrance” (dhruvånusm®tiª), character-ized by intense love, the vision of the Supreme is attained. But note that I say not “union” with God, rather a vision that is in some sense union, by its intensity. This is “God-knowledge,” the vidya or upåsanå spoken of in the çrutis.31 In short, ordinary knowledge, though not to be disdained, is not sufficint for “salvation” or “liberation,” which comes through bhakti, a certain, perhaps “higher knowledge” through which God can be “seen.” Thus the Song of the Blessed: “I am attain-able only through undivided bhakti” (G⁄ta XI.54). Jehudah: In my view there exists a separate “faculty,” higher than understanding, where “communion” with God is achieved (ha-inyan, ha-elohi)—this indicates both sides of the relation: objectively, from God alone; subjectively, in language and logic, from our power to ap-percieve. Though in one sense we must be silent before Him, we are importuned to “listen” to

the works His hand hath wrought Let them declare; and may lips o’erbrim With singing and their voice be loud with praises frought. Tongues fulfilled of speech, Exalting, crowning, telling o’er His praise; Souls be extolling, still discerning ways, To learn and tell and teach…32

Abelard: God is more than the world He created, certainly. Though, according to our faith and clear reason, wherever a faithful soul may be, there it finds God, since he is present everywhere; “beatitude” we receive from the vision of God which he infuses into us and which we do not apprehend by our own power. We certainly do not mount up words to apprehend the brightness of the material sun, but it sheds its light on us for us to enjoy. Likewise, it is not so much that we ap-proach God as that He approaches us, shining his brightness on us and the heat of his love from above…sorry? Yes perhaps we could say ta-

James Mark Shields ❖ 151

pas… (Dial. 139–40). As you, Halevi, have just expressed in your lovely poem, we can, with some adequacy, speak and describe God’s creation, or perhaps, as we panentheists might say, God-in-creation, or Brahman-as-qualified by the world and souls; but we can never reach Brahman as the source and sustainer of creation and existence. For as the Evangelist tells us “The one who is of the earth speaks on an earthly plane” (Jn. 3:31). In speaking of these things we use, at best, similes and parables, as did Our (excuse me) My Lord Jesus Christ. For us Christians the work of Christ is one of illuminating wisdom and our incitement to responsive love in human conduct (Theo. I.4). Jehudah: These are saintly words which are more than philosophic; indeed, they deserve the name of wisdom, not philosophy.33 But we come full circle, for it seems we are back to discussing “attributes,” which, as I think we all agree, have neither direct correlation to sub-stance, nor are they merely signs which point to essences. They are symbols, concepts from which substance, universality, can be glimpsed. But only imperfectly, if without the infusion of grace through devo-tion. For none applies a distinct name for God except he who hears His address, command, prohibition, approval for obedience and re-proof for disobedience (Kuz. IV.3). But here is Rabbi Maimon. [a man approaches from the other side of the square, hurriedly, about to burst with excitement] My dear Rabbi, what ails ye? Rabbi Maimon: Dearest Jehudah…I have a son, he has just been birthed…we have called him Mosheh34…praise to YHWH…greetings sirs…but I must return… [leaves] Jehudah: Indeed, a scholar has been born to the world; for in Cór-doba’s light the son of the learned Maimon cannot help but become a sage. We only hope he shall be a man of faith, as well, seeking knowl-edge and concord, in the spirit of outr present colloquy, ever-mindful of the Supreme.

152 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

Conclusions Jehudah: In short, what is key is the spirit in which we offer devotion, and in which we acquire and search for knowledge, and in which we do our duties (selflessly, as per your G⁄ta and our Scriptures). Fear, love and joy are equally valid “approaches” to God. Just as prayers demand devotion, so also is a pious mind necessary to find pleasure in God’s command and law… (Kuz. II.50) Knowledge and philosophy are well suited to, and must grow out of, an active life of belief. Abelard: Credo nos in fluctu eodem esse.35 For myself, I do not wish to be a philosopher if it means conflicting with Saint Paul, nor to be an Aris-totle if it cuts me off from Christ (Conf. 270). One must give way nei-ther entirely to authority nor to shallow cleverness in argument. Yet in order to come to reconciliation, we must talk of these things, rooting out both the unity and diversity of our “ways.” For “worlds can be different although they contain exactly the same things.”36 God con-sidereth not action, but the spirit of the action. It is the intention, not the deed, wherein the merit or praise of the doer consists (Eth.). Råmånuja: Certainly, we should not assume a Unity in our own thoughts, though they show remarkable congruence, or perhaps, to use a more adequate term, “confluence,” given their different sources, our various backgrounds and unsaid assumptions. Rather, let us see the Unity in our own Diversity, the modal and situational variegations which, though ancillary to the substance of our speech–the possible agreement of our ideas in the Supreme–are nonetheless very real and undeniable, and must not be washed away as floodbanks in the spring, merely for the sake of dialogue and communion. For speech, as critical and formative (even divine) as it may be, can only build the bridge over which we must cross; the crossing itself is another matter. What is certain is that, if we began today’s discussion under the sign of Arya-man, in Vedic literature the god of formal hospitality, we have ended it under Mitra’s protection, the god of intimate friendship among one’s own kind. Jehudah: It grows late, and Master Råmånuja must leave us tomorrow in the early hours. A word before we break this enjoyable and informa-tive gathering of three worlds (four, before young Roshd was called away by his doting mother). Let me offer a prayer of sorts, to which I think we would all adhere, in summation of these Córdoban dis-

James Mark Shields ❖ 153

courses: “So maketh He man’s eyes luminous to look upon the Light” (Poems 173). Råmånuja: And I would add, if I may, a prayer of my own tongue, which strikes a similar chord:

TAT SAVITUR VARENIAM BHARGO DEVASYA DHIMAHI

DHIYO YO NAH PRACODAYAT.37

Endnotes 1. J(eh)udah Halevi (or ben-Samuel, Arabic name Abu’l-Hasan), foremost Hebrew poet of the Middle Ages, and author of the philosophical-theological dialogue The Kuzari (Kitab Al Khazari, 1130–40, thus in progress in 1135), which purports to expound the principles of the three Abrahamic faiths as well as Aristotelian philosophy; born c. 1086 C.E., thus aged 48–49 at the time of the present colloquy.

2. Peter Abelard (or Pierre Bailard), Christian philosopher-theologian, the first “scholastic,” and a proto-humanist; born 1079 C.E., thus about 55 or 56 at this time. J. Ramsey McCallum: “The ancient philosophers, their Roman and medieval successors, the prophets and seers of Israel, the Scriptures, and the Christian Fathers, all these he introduced to one another and found in their speech a common note” (McCallum 1948, v).

3. Çr⁄ Råmånujåcårya (herein Råmånuja), Indian sage and founder of the school known as Viçi‚†ådvaitavedånta; date of birth is disputed, said to be c. 1017 C.E., thus making him a venerable 117–18 here, at any rate within several years of his reputed death in 1137 C.E. Råmånuja travelled much in his ex-tended life, conversing and disputing with other theists, and was in exile in his later years, a period that included contact with the Muslim king at Delhi, who no doubt had friends and relations in the Moorish capital…

4. Apart from the fact that John of Salisbury heard him lecture in Paris in 1136, nothing is known of the whereabouts of Abelard from his quitting the abbey at St. Gildas in the early 1130s to the late years of that decade, when he returned to the limelight in his confrontation with Bernard of Clairvaux (Radice 1974, 34–35). Wherever he was, he completed in these years Sic et Non, Ethica, and the Dialogue of a philosopher with a jew and a christian, and seemed to have gained renewed spirit. The Dialogue, whose date has been dis-puted, but seems to be placeable in this period, led Pierre J. Payer to comment on the close parallel between such and The Kuzari of Halevi, Abelard’s con-temporary: “There is a surface similarity between the two which is quite strik-ing…However, I know of no possible contact nor a common sourse which

154 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

might explain what seems to be a coincidental parallel” (Payer 1979, 10). Where was he during these years? We know that around 1130, in despair of persecution, Abelard thought seriously of “quitting the realm of Christendom and going over to the heathen (i.e., Saracens, Moors?), there to live a quiet Christian life…” (Story 94). Hmmm…

5. Peter Lombard (1100–64), a pupil of Abelard in Paris, wrote his famous Sentences, a seminal theological text up to Luther’s day, using his master’s dia-lectical treatise Sic et Non.

6. Arnold of Brescia (or Arnaldo da Brescia, 1100–55), Italian religious and political reformer and agitator, one time student of Abelard, he was eventually condemned by St. Bernard, executed and his body burned. Abelard is uncon-sciously prophetic, for Brescia was “damnable” indeed.

7. Abelard refers to the “Story of His Calamities” (Historica calamitatum, as he titled his autobiographical “apology”); the relation, in large part, of his affair with Héloise, which came to a brutal end at the hands of her enraged uncle Canon Fulbert, whose thugs unmanned the scholar, sending both he and her into holy orders, and thereby making of Abelard and Héloise hero-figures for romantics throughout the ages.

8. Abelard refers to Råmånuja’s fight and break with his wife, who placed caste-differences over hospitality and devotion.

9. Ibn Sina (or Avicenna, 980–1037), Arabian philosopher and physician; like Halevi, and many Muslim and Jewish thinkers of the time, master of these two realms.

10. Ibn Roshd (or Averroës, 1126–98), was of course to become the greatest of Moorish thinkers; he is most particularly known for his commentaries on Aris-totle, many of whose writings were lost to the Latin West until resurrected in the 12th and 13th centuries through retranslation from the writings of Arabic scholars.

11. In fact, what Råmånuja speaks of is to occur over the next few centuries, and will eventually contribute to the great schism of the Reformation in Chris-tianity; viz. the scholastic disciples of Anselm, Abelard, and Aquinas lose their focus, forgetting the point of their dialectics and the aim of their knowledge—God. In some sense, Råmånuja is the Martin Luther of Vedånta, calling for a return to faith and grace over mere “works” and abstruse metaphysical quib-bling (see note 30).

12. Abelard refers to his De unitate et trinitate divina (Of Unity and the Holy Trinity), written about 1120 and later reworked as the first section of his The-ologia. Both works were the subject of much controversy; the former was con-demned, and Abelard called to a Synod at Soissons (1121) where, devoid of a defense, he was importuned to burn the book with his own hands. In De uni-

James Mark Shields ❖ 155

tate he explains the nature of the Christian Trinity by logic, reason, and analo-gies like that above.

13. He writes to his son Astrolabe: “Tut fidei sectis divisus mundus habetur…” (“The world is divided into so many religious schools of thought…” (Dial. 20 n. 3). And Abelard does not have in mind solely the Abrahamic faiths, alluding in his Theologia to Indian philosophy, however misinformed he was in this regard (I.1164). McCallum notes that “(t)his reference to the Brahmans indi-cates the range of Abelard’s philosophy in contrast to medieval limits” (1948, 56–57 n. 3). 14. Cf. Augustine’s distinction within the Godhead of ingenitas, genitas, proce-dens.

15. Much of the young Muslim’s argument is taken, again, from Abelard’s Theologia (1237D, 1238A). The last line comes from the Qur’an, Surah 19:89, a condemnation of the blasphemy of the Christians in imputing to God the begetting of a Son!

16. Strangely, this sentence of Råmånuja makes an anagram which spells “A.N. Whitehead.” Whitehead (1861–1947) is of course the twentieth-century Brit-ish logician, philosopher, and father of “process theology,” who seems to hold a very similar conception of the divine to Råmånuja, and who could probably be called, with some justice, a “panentheist.” The Process God’s nature is “the composite nature of all the actualities of the world, each having obtained its unique representation in the divine nature” (Mellert 1975, 47). See White-head 1978, esp. parts I and V.

17. Abelard studied under the famed Platonist (“realist”) William of Cham-peaux (c.1070–1121), as well as the arch-nominalist (and for this, ill-fated) Jean Roscelin of Campeigne (Roscellinus, c.1050–c.1120), thus imbibing both the still-dominant idealism and the emergent upstart challenge of nominalism.

18. Abelard echoes this sentiment in his Dialogue: “I…more desirous of learn-ing than of judging…” (Dial. 71).

19. “At vero, cum de sensu propositionis exponuntur, proprie modales non sunt, nec universales vel particulares vel indefinite vel singulares, nec ideo simplicium conversiones retinent…” (Tweedale 1976, 256).

20. Vedånta I.i.1. Lipner: “[T]he correlatively predicated expression indicates that a particular thing (the referent) is the basis of a co-presence of more than one determination such that it gives grounds for the predication of several non-synonymous terms in respect of it” (1986, 29).

21. Kuz. IV.25. Halevi borrows this mystical cosmogony from the pseudepi-graphal Book of Creation.

22. Halevi has been considered a precursor of modern existentialist religious

156 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

philosophers such as Martin Buber (1878–1965) and Franz Rosenzweig (1886–1929), the latter of whom saw the medieval poet as a forerunner and muse of his own philosophic method of Sprachdenken (speech-thinking). See Galli 1994.

23. Abelard’s use of “theology” as the title of his last work was controversial (Bernard called it “brazen”), for this term retained its original sense of what we might today call “classical mythology”; that is, storytelling about the gods of the Greco-Roman pantheon. Abelard brought the term into acceptability, though his own use may have retained some of its ancient meaining, as some-thing “other than” pure philosophical talk about God…

24. Theol. 1215B. Thus Abelard’s “humanism” long before the Renaissance. Another of his pupils, William of Conches, was instrumental in developing the plea for more inclusive study, of literature and the classics, in “theology.”

25. Divya-sthana is God’s celestial abode; thus the meaning of the first part of this epipthet is a strong evocation of “never,” for God’s heavenly “home” can never “fly over land” (see Carman 1974, 168).

26. Once again, Råmånuja prophesyses through anagram, this time his sen-tence—which seems to imply that the “theology” which the three are creating in their discussion will tumble all comers, from the side of the mystic pietists as well as from the philosophers—spells the name Rudolf Otto (1869–1937), a twentieth-century phenomenologist of religion who takes Råmånuja’s side against Çaπkara in the “battle for God.” Otto argues, quite correctly I think, that Råmånuja is as interesting a “theologian” as a “philosoper”—his philoso-phy is, however important, a tool to be confirmed by experience and grace. Cf. Carman 1974, 200.

27. A theological school of dialecticians (their naming means literally “the takers”) who are criticized by Halevi in The Kuzari V.10.

28. From Halevi’s “Nature and Law” (Poems 173).

29. Endymion is a figure from classical Greek mythology whose beauty caused the moon to fall in love with him while he was sleeping on Mount Latmos. She made him sleep everlastingly so that she could look upon his beauty for ever. In this sentence of Råmånuja, “Endymion’s route” thus implies the state of dormancy. Thus, his meaning seems to be: Unless these truths stay dormant, let God-who-is-in-the-Self reveal the connection between God (Nåråyå~a) and the “I.” Where the Indian learned his Greek mythology cannot be ascer-tained…

30. Here we have a subliminal invocation of Protestant Reformer and Saxon firebrand Martin Luther (1483–1546), for whom, as with Råmånuja, “works” without faith are useless, and “justification” ultimately comes through “faith” alone (Cf. G⁄ta 17.28: “but work done without faith is ASAT, is nothing: sacri-

James Mark Shields ❖ 157

fice, gift, or self-harmony done without faith are nothing, both in this world and in the world to come”; and Luther, in his “Preface to the New Testament”: “the gospel demands no works to make us holy and to redeem us. Indeed, it condemns such works, and demands only faith in Christ…”). Råmånuja’s use of anagrams may well be in deference to Halevi’s own tradition, and the Kab-balistic penchant for acrostics in particular, or he may have picked up this talent from his own beloved pupil Kuruttalvar, who penned a cryptic acrostic poem entitled Yamakaratnakaram, before his eyes were plucked out in defiance of Råmånuja’s persecutor, the Cola king.

31. “One who knows Brahman attains the Supreme” (Tait. Up. II.1); “He who knows Brahman becomes Brahman” (Mand. Up. III.2.9).

32. From Halevi’s “Nature and Law” (Poems 173).

33. Jehudah echoes verbatim Héloïse’s words to Abelard in Letter I of their famed correspondence (Letters 114).

34. The newborn child, Mosheh ben Maimon (Arabic name Musa ibn Maimun, but known to the world as Maimonides), is of course the great Jew-ish scholar who would write the influential More Rehobin (Guide to the Per-plexed), and who would attempt to fuse Aristotelian and classical thinking with Jewish faith and learning. Alas, Maimonides was not destined to bask in the “light” of Córdoba, as the tolerant intellectual center dimmed with the Almohad overthrow of the Almoravids in 1145, and with the continuing “suc-cess” of the Christian reconquista of the Iberian peninsula. His family was forced to renounce their faith and flee to North Africa and the Middle East, where Maimonides died (in Cairo) in 1204.

35. L.: “I think we are on the same wavelength.”

36. Abelard “quotes” Martin M. Tweedale, a modern commentator, who says that this phrase can be seen as “the ontological consequence of Abelard’s logic and semantics” (Tweedale 1976, 304). McCallum notes, especially in his Dia-logue, Abelard’s “penchant for religious reconciliation that must have been as rare in the Middle Ages as it has been until very recent years” (2); indeed, one could say this attitude was almost unheard of, in Christianity, before Raymond Lull (1232–1316) and Nicolas Cusanus (1401–64), and rare even in the time of G. E. Lessing (1729–81), whose 18th-century play of tolerance Nathan der Weise was an anomaly. It might be noteworthy to add that, as Abelard was seeking these “points of contact,” his nemesis Bernard of Clairvaux was busy preaching the Second Crusade against the “infidel,” in 1146.

37. “Let our meditation be on the glorious light of Savitri [“Impeller,” god of the rising and setting sun]. May this light illumine our minds” (Quoted in Mascaró’s Introduction to the Bhagavad-g⁄ta, 10). This is the famous gayatri, a prayer which has been on the morning lips of Indians for some three millenia.

158 ❖ Córdoban Discourses

Works Cited

Abelard, Peter. 1974. Historia calamitatum: Abelard to a friend—The story of his calamities. In The letters of Abelard and Héloïse, translated by Betty Radice, 57–108. London: Penguin Books. Cited as Story.

———. 1974. The personal letters and the letters of direction. In The letters of Abelard and Héloïse, translated by Betty Radice, 109–269. London: Penguin Books. Cited as Letters.

———. 1974. Confession of Faith. In The letters of Abelard and Héloïse, trans-lated by Betty Radice, 270–71. London: Penguin Books. Cited as Conf.

———. 1979. A dialogue of a philosopher with a Jew, and a Christian. Translated

by Pierre J. Payer. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. Cited as Dial.

———. 1983. Selection from Sic et non. In the Middle Ages, edited by Brian Tierney. New York: Knopf.

Adidevananda, Swami. 1968. Foreword to Råmånuja, Vedartha-Sangraha. Translated by S. S. Raghavachar. Mysore: Çr⁄ Ramakrishna Ashrama.

The Bhagavad g⁄ta. 1962. Translated by Juan Mascaró. London: Penguin Books.

Carman, John Braisted. 1974. The theology of Råmånuja: An essay in interreligious understanding. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Galli, Barbara. 1984. Rosenzweig’s philosophy of speech-thinking through response to the poetry of Jehuda Halevi. Studies in Religion 23 (4):413–28.

Halevi, Judah. 1964. The Kuzari: An argument for the faith of Israel. Trans. by Hartwig Hirschfield. New York: Schocken Books. Cited as Kuz.

––––––––––. 1928. Selected poems of Jehudah Halevi. Edited by Heinrich Brody. Translated by Nina Salaman. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America. Cited as Poems.

Hartshorne, Charles. 1987. Panentheism. Entry in the Encyclopedia of Religion, volume 18, 165–71. New York: Macmillan.

Lipner, Julius. 1986. The face of truth: A study of meaning and metaphysics in the Vedantic theology of Råmånuja. Albany: SUNY Press.

McCallum, J. Ramsay. 1948. Abelard’s Christian theology. Oxford: Basil Black-well. Includes substantial selections from Abelard’s Theologiae christiana, translated by J. Ramsay McCallum. Cited as Theo.

Mellert, Robert B. 1975. What is Process Theology? New York: Paulist Press,

James Mark Shields ❖ 159

Payer, Pierre J. 1979. Introduction to Peter Abelard, A dialogue of a philosopher with a Jew, and a Christian. Translated by Pierre J. Payer. Toronto: Pontifi-cal Institute of Mediaeval Studies

Radice, Betty. 1974. Introduction to The letters of Abelard and Héloïse. Trans-lated by Betty Radice. London: Penguin Books.

Raghavachar, S. S. 1972. Çr⁄ Råmånuja on the Upani‚ads. Madras: Vidya Press.

Råmånujåcårya, Çr⁄. 1904. The Vedånta S¨tras with the commentary of Råmånuja. Translated by George Thibaut. Sacred books of the East XLVIII. Oxford: Clarendon Press. This work is also known as the Çr⁄bhasya, and, in its shorter versions, the Vedåntasara and the Veddantadipa. Cited as Vedånta.

———. 1968. Råmånuja on the Bhagavadg⁄ta: A condensed rendering of his

G⁄tabhasya with copious notes and an introduction. Translated and edited by J. A. B. Van Buitenen. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. Cited as Bhasya.

———. 1968. Vedartha-Sangraha. Translated by S. S. Raghavachar. Mysore: Çr⁄ Ramakrishna Ashrama. Cited as Sang.

Tweedale, Martin M. 1976. Abailard on universals. Amsetrdam: North-Holland Publishing Co.

The Upanishads. 1965. Translated by Juan Mascaró. London: Penguin Books.

Each Upanisad cited separately.

Whitehead, Alfred North. 1978 [1929]. Process and reality: An essay in cosmology. New York: Free Press.