Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing ...ledochowicz.com/ftp/dodatkowe_zdjecia/Yale...

-

Upload

truongthuy -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

1

Transcript of Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing ...ledochowicz.com/ftp/dodatkowe_zdjecia/Yale...

Asia Society Museum

in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London

Edited by Ive Covaci

REALISM AND SPIRITUALITY IN THE SCULPTURE OF JAPAN

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

President’s Foreword | Josette Sheeran 00Museum Preface | Author 00Curator’s Acknowledgments | Ive Covaci 00Funders of the Exhibition 00Lenders to the Exhibition 00Note to the Reader 00

ENLIVENED IMAGES: BUDDHIST SCULPTURE 00 OF THE KAMAKURA PERIOD Ive Covaci

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE KEI SCHOOL Samuel C. Morse 00

SOFTENING THEIR LIGHT, MINGLING WITH THE DUST: 00 JAPANESE GODS IN BUDDHIST ART Hank Glassman

THE TRANSFER OF DIVINE POWER: 00 REPLICAS OF MIRACULOUS BUDDHIST STATUES Nedachi Kensuke

CATALOGUE Ive Covaci and D. Max Moerman 00

FORM AND PRESENCE 00

RITUAL AND DEVOTIONAL CONTEXTS 000

EMPOWERING INTERIORS 000

Map 000 Timeline of Selected Artistic, Historical, and Religious Events 000

of the Kamakura PeriodGlossary 000Selected Bibliography 000Contributors 000Index 000Photography Credits 000

Published with assistance from <to come, if applicable>

Published on the occasion of the exhibition “Kamakura: Realism and Spirituality in the Sculpture of Japan,” organized by Asia Society Museum.

Asia Society Museum, New York

<exhibition dates>

© Asia Society, New York, NY, 2016.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Published by

Asia Society 725 Park Avenue New York, NY 10021 AsiaSociety.org

Yale University Press P.O. Box 209040 302 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06520-9040 yalebooks.com/art

Designed by <to come> Set in <to come> type by <to come> Printed in <to come>

Library of Congress Control Number: <to come>

ISBN 978-0-300-21577-9

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The paper in this book meets the requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Jacket<or Cover> illustrations: (front) <to come>; (back) <to come>

Frontispiece: <to come>

CONTENTS

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

vi vii

Japanese Historical Periods

Asuka Period 538 –710Nara Period 710 –794Heian Period 794 –1185Kamakura Period 1185 –1333Nanbokucho Period 1336 –1392Muromachi Period 1392 –1573Momoyama Period 1573 –1615Edo Period 1615 –1868Meiji Restoration 1868 –1912

For Japanese names, the surname is cited first, followed by the given or the artist’s name. This does not apply, however, to those who publish in the West and/or who have opted to use the western order of their names. In discussion, Japanese artists and historical figures are referred to in the form most commonly cited, usually by the given or art name. Shunjobo Chogen, for example, is known as Chogen.

Japanese is rendered in the modified Hepburn Romanization system. The macron is used to indicate a long vowel in Japanese (Fudo Myoo), except where the Japanese name or term has entered the English lexicon (shogun). Names and terms are provided in the Japanese kanji system in the glossary.

In the text, Sanskrit names and words are tran-scribed without diacritical marks. Diacritical marks appear in the Sanskrit version of terms cited in the glossary for the reader’s reference.

NOTE TO THE READER

Asia Society, New YorkBritish MuseumBrooklyn MuseumThe Cleveland Museum of ArtLarry Ellison CollectionHarvard Art MuseumsKimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TexasThe Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkMinneapolis Institute of ArtsMuseum für Ostasiatische Kunst, KölnMuseum of Fine Arts, BostonMuseum Rietberg ZürichNew York Public Library Odawara Art FoundationPhiladelphia Museum of ArtSeattle Art MuseumTokyo National MuseumJohn C. Weber Yale University Art Gallery

Major support for “Kamakura: Realism and Spirituality in the Sculpture of Japan” comes from TKTK.

Additional support is provided by Toshiba International Foundation and the Japan Foundation.

Support for Asia Society Museum is provided by Asia Society Contemporary Art Council, Asia Society Friends of Asian Arts, Arthur Ross Foundation, Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation, Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions, Hazen Polsky Foundation, New York State Council on the Arts, and New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

<additional funders to come>

FUNDERS OF THE EXHIBITION LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

viii 1

When you think about an object carved from wood or drawn in a picture as if it were a living being, then it is a living being.

—Myoe (1173–1232)

Who would call this a mere wooden image of a deity? . . . How could it not possess the majesty of a living body?

—Eison (1201–1290)

The vigorous, expressive, and beautiful sculptures of Kamakura-period (1185–1333) Japan display an uncanny realism. Face to face with the masterworks illustrated in this catalogue and presented in the associated exhibition we can identify with the thirteenth-century Japanese monk Eison, who describes an icon he has just dedicated as possessing the “majesty of a living body.”1 Often described as a sculptural renais-sance, works of the Kamakura period possess naturalistic proportions and a sense of movement, life-like facial expressions with eyes of inlaid crystal that reflect light, and realistic drapery.2 With many extant signed and dated works, art historians have been able to trace individual sculptors’ styles and to tell us much about the master artists and their patrons. At the beginning of this period, sculptors looked back to art of the Nara period (710–794), which is also characterized by a high degree of naturalism. Tech-nical and stylistic innovations in the twelfth century allowed sculptors to depart from the more abstracted and idealized sculpture of the Heian period (794–1185) to create statuary that exudes the immediacy of the deity in more approachable, humanlike form (see cat. no. 3).

ENLIVENED IMAGESBUDDHIST SCULPTURE OF THE KAMAKURA PERIOD

Ive Covaci

Detail of cat. XX (see page XX)

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

2 3

Japan, it seems ideal to consider it within the contexts of the stunning objects of devo-tion and assimilative religious inclinations of this short, turbulent era.

THE KAMAKURA PERIOD IN HISTORY: DISRUPTION AND INNOVATION

The 150-year span we call the Kamakura period is bracketed by civil wars that severely disrupted political, social, religious, and artistic institutions. Armed conflicts between rival warrior clans and aristocratic powerbrokers became increasingly common in the twelfth century until a large-scale civil war in the 1180s pitted the Kyoto-based Taira war-rior clan against the ultimately victorious Minamoto clan from the east (fig. 1). The conflict caused the burning to the ground of the great ancient temples of Kofukuji and Todaiji in the old capital of Nara in 1180 by Taira forces. Following this devastation of architecture, libraries, and artifacts, work began almost immediately on the temples’ rebuilding and sculptural repopulation under imperial, aristocratic, and warrior patronage—even small donations solicited from among the broader population. This urgent need to replace old icons and buildings, in quantity and quality, was a significant factor in stylistic change during the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries.

While the last century of the Heian period saw the rise to power of warrior elites within the existing aristocratic court structure, it was not until 1192 that a warrior chief-tain, Minamoto Yoritomo (1147–1199), was given the title “great barbarian-quelling general” (sei-i-tai-shogun). Yoritomo had established a bona fide military government

Enlivened Images

What Eison means by “the majesty of a living body” goes far beyond the idea of formal, external resemblance to earthly beings. As religious icons, these images were enlivened by their function as objects of ritual and devotional focus. Whether installed as the principal icon (honzon) of a temple hall, as the focus of a discrete esoteric ritual, or as a vehicle for personal devotions, the material image is transformed into an embod-iment of divine presence during the act of worship.3 This sense of embodiment is enhanced by the practice of depositing sacred relics, texts, and even miniature images within the hollow interior of many sculptures. Such forms of enlivenment have received a great deal of scholarly attention in the past decade in both Japan and the West, and this exhibition and catalogue draw extensively on recent work in the fields of Japanese art history and religious studies.4

This essay intends to outline historical conditions of the Kamakura period and to introduce the three sections of the exhibition: “Form and Presence” examines stylistic and technical developments in Kamakura sculpture; “Ritual and Devotional Contexts” centers on enlivenment through worship; “Empowering Interiors” interprets the practice of making sacred deposits in statues. The subsequent essays in this volume by leading scholars of Japanese art and religion explore significant aspects of these topics. Samuel C. Morse explains the development of the innovative Kei school of sculptors. Hank Glassman discusses religious pluralism in art combining belief in the native gods (kami) and the buddhas. Nedachi Kensuke shows how the practice of copying miraculous images served as a means of transferring sanctity between icons. Although the treat-ment of icons as enlivened images is by no means limited to the Kamakura period in

FIGURE 1. Detail from Night Attack on the Sanjo Palace, from the Illustrated Scrolls of the Events of the Heiji Era (Heiji Monogatari Emaki). Second half of the 13th century. Handscroll, ink and color on paper. Image H. 16¼ x W. 27511⁄16 in. (41.3 x 700.3 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Fenollosa-Weld Collection, 11.4000.

This illustrated handscroll from the Kamakura period depicts one of the tumultu-ous events of the mid-twelfth century, the Heiji Disturbance of 1160, when a warrior- aristocrat alliance staged a coup, kidnapping the retired emperor and emperor and burning the palace.

Ive Covaci

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

4 5

GoDaigo (reigned 1318–1339) endeavored to overthrow the shogunate and restore imperial authority by appointing his own son and heir crown prince in defiance of the alternation system. This restoration was short-lived, however, and GoDaigo fled south to Yoshino when his former ally, the warrior Ashikaga Takauji (1305–1358), took Kyoto and appointed a new emperor. The end of the Kamakura shogunate, the schism in the impe-rial court, and the establishment of the Ashikaga shogunate in Kyoto initiated a period of instability that lasted for much of the remaining fourteenth century (the so-called Nanbokucho jidai, “Period of Southern and Northern Courts”) and to a great extent endured for the next three hundred years.

BUDDHISM AND PATRONAGE IN THE KAMAKURA PERIOD

Within this era of political change, a great diversity of Buddhist temples and movements flourished. Mahayana Buddhism—which teaches the existence of universal, timeless buddhas, holds up the bodhisattva ideal of compassion, and promises the possibility of salvation for all sentient beings—had first entered Japan in the sixth century via China and Korea, whereupon it quickly attracted patronage from the court and powerful clans. During the Nara period, the religious landscape was dominated by the so-called Six Nara schools and the great temples Todaiji, supported by the imperial court, and Kofukuji, sponsored by the Fujiwara family. With the transfer of the capital to Kyoto in the late eighth century, the Nara schools were largely supplanted by the Tendai and Shingon schools centered at temples in and near Kyoto. These schools were founded in the early ninth century upon the return of the monks Saicho (767–822) and Kukai (774–835) from China, bringing new esoteric teachings and ritual forms they had encountered on the continent. A mainstay of these new, esoteric temples and their clerics was the perfor-mance of large-scale rites for the protection of the state and sovereign, along with pri-vately commissioned rituals for worldly benefits, such as healing illnesses, conception and safe birth of heirs, political advancement, and defeat of one’s enemies. In the Kama-kura period, as in the preceding centuries, Buddhism serving the court was dominated by these Tendai and Shingon-affiliated temples around the capital. The Kyoto-based sculpture workshops that filled their demand for images likewise continued to receive patronage from the imperial and aristocratic families. The emerging elite warrior class, including the shogunal household and high-ranking vassals around the country, also patronized esoteric institutions, perhaps in an attempt to harness the legitimacy of established institutions for their own purposes.

The Kamakura period also ushered in a revival of the old schools of Buddhism cen-tered in the old capital of Nara, undoubtedly aided by the flurry of rebuilding temples after the destruction of the 1180s. These Nara schools traditionally emphasized the monastic rules, or vinaya, and the academic study of Buddhist doctrine and textual traditions. In this period, however, innovative Nara-based monks such as Jokei (1155–1213) and Eison (1201–1290) stressed devotion to the historical Buddha Shakyamuni and brought about a concomitant increase in the worship of relics, considered the cor-poreal remains of the Buddha. These beliefs and practices relate closely to the idea of enlivened images because many of these monks were concerned with establishing an immediate connection to the historical Buddha in their time.

Along with continuity and revival, a number of new movements developed and found popular appeal in the late Heian and Kamakura periods. Often founded by char-

Enlivened Images

(called a bakufu, “tent government”) based in eastern Japan in the town of Kamakura, from which the period takes its name. Although Yoritomo’s sons inherited the title of shogun after his death, real power quickly concentrated in the hands of his in-laws, the Hojo clan. Members of this family ruled throughout the period as regents for figure-head shoguns, often young princes brought to Kamakura from Kyoto. An important innovation of the new military government was granting appointments as estate over-seers ( jito) and provincial constables (shugo) to loyal vassals and political allies, thus consolidating the shogunate’s network of fealty throughout the country. It must be noted, however, that this military government coexisted with, and continued to at least nominally derive its authority from the imperial court in Kyoto, in what historians call a dual-polity system.5 Nevertheless, the Jokyu War of 1221, in which the retired emperor GoToba’s (1180–1239) attempt to overthrow the military government ended in spectac-ular failure, represented the symbolic solidification of military rule from Kamakura. It must have been apparent to contemporaries that the warrior ascendancy was not a temporary upset.

The Kamakura period can be seen as a transitional one—from the old aristocratic order of the Heian period to a new feudal system that persisted in the Muromachi (1336–1573) and subsequent periods. While Kyoto’s aristocratic elite continued to dominate as cultural tastemakers, new sources of patronage and popular developments in religion also began to have an effect upon artistic and literary production. These simultaneous forces of conflict, change, and continuity are perhaps what fostered the innovation and pluralism—of government, of religious practice, of artistic output—that characterize the Kamakura period.

Contact with Song-dynasty (960–1279) China also had a significant impact on developments in Kamakura culture. Sustained diplomatic, commercial, religious, and artistic exchange with the Asian mainland increased in the twelfth century.6 In the rebuilding of the great temples of Nara in the 1180s and 90s, newly imported Chinese modes of architecture were employed, and immigrant Chinese craftspeople played important roles in these projects. Monks went back and forth between Japan and China with increasing frequency, bringing with them ideas and artifacts. The Japanese monk Chogen (1121–1206), who had reportedly visited China, spearheaded the fundraising campaign to rebuild Todaiji, and the grand ceremony for consecrating the temple’s reconstructed Great Buddha was attended by multiple monks from the continent.7 But this flourishing cultural exchange was soon impeded by the Mongol Empire’s expansion across China. After a long struggle, the Southern Song dynasty finally fell in 1279, and Japan itself experienced an unprecedented threat from abroad with attempted Mongol invasions in 1274 and 1281. Neither attempt was successful, thanks in part to the fortu-itous occurrence of a typhoon that hampered the invading forces and helped the Japa-nese defenses hold. The victory reinforced the legitimacy of the shogunate and boosted the claims of the shrines and temples that credited their fervent rituals and prayers with calling up the storm. Still, the cost associated with maintaining a defensive force, cou-pled with the lack of war spoils and land to redistribute, ultimately contributed to the weakening of the Kamakura shogunate.

As for political developments at court, the shogunate’s attempt to control imperial succession by forcing heirs from two different lines of the imperial family to alternate had already resulted in the fragmentation of the court into competing factions. In the 1330s, with the help of warrior clans disenchanted with Hojo family rule, Emperor

Ive Covaci

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

6 7Ive Covaci

ismatic monks departing from established institutions, such as Honen (1133–1212) and Shinran (1173–1263) who emerged from the Tendai center of Mount Hiei, these move-ments are characterized by their focus on single deities or texts, accessible paths to sal-vation, and broad appeal to the masses. Although sculpted and painted icons had important purposes in many of these movements, they generally required fewer and less elaborate images for worship than the traditional Buddhist sects, and thus afforded more opportunities for people of all social classes to participate. Many of the move-ments were focused on the worship of Amida, the Buddha who descends to welcome the soul of the faithful on his or her deathbed for rebirth in paradise. The immediacy of the idea of meeting with the Buddha at the moment of death relates closely to the sense of presence and action in “this world” that characterizes imagery of this period.

It was also during the Kamakura period that the Zen school of Buddhism, newly imported from China, began to gain prominence and patronage. While Zen found adher-ents among various social classes, in eastern Japan the shoguns, their regents, and elite warriors served as major patrons. It is often said that Zen particularly appealed to the military class because of its emphasis on discipline and direct access to enlightenment, rather than on elaborate ritual and imagery. The strong tradition of realistic portraiture of Zen masters that flourished in these institutions must be kept in mind when assessing realism in Kamakura sculpture in general. A portrait sculpture of the Zen master Hotto Kokushi (1207–1298) is a rare example in western collections (fig. 2).8 As various schol-ars have demonstrated, the treatment of statues as enlivened presences was no less pronounced in the Zen setting.9

Rather than stressing sectarian divisions between “old” and “new” Buddhism, or establishment and popular Buddhism, recent scholarship on Kamakura religion empha-sizes the pluralistic character of the period. More than representing a broader sect or school, clerics saw themselves as following in a specific temple’s lineage, and it became increasingly common for monks to combine thoughts and practices from multiple tradi-tions.10 Beliefs in the native gods (kami ) also played a key role in the Kamakura religious landscape, especially in Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, wherein the native gods were seen as manifestations of Buddhist deities (honji-suijaku). See Hank Glassman’s essay in this volume for further discussion of this topic and its repercussions in sculpture. The diver-sity of imagery in this exhibition is a testament to the dimensions of this pluralism.

REALISM AND SPIRITUALITY IN THE SCULPTURE OF JAPAN: THE EXHIBITION

form and presenceThe exhibition first considers formal expression, stylistic change, and technical achieve-ments in Kamakura-period sculpture. Included are a number of works signed by their makers, rare in western collections, and others that can be confidently attributed to specific sculptors or their immediate workshops. The works demonstrate the tendencies toward intense realism and expressive movement, on the one hand, and gentle natural-ism and worldly sweetness, on the other.11

Although we know the names of many sculptors of the preceding centuries through documents, it was not until the Kamakura period that sculptors began signing their works with any regularity, usually on the tenons attaching the feet to the bases or on the interiors (see cat. no. 9). Masters such as Unkei (d. 1223), Kaikei (active 1183–1236; see

Ive Covaci

FIGURE 2. Portrait of the Zen Master Hotto Kokushi. Kamakura period, c. 1286. Wood with hemp cloth, black lacquer and iron clamps. Overall H. 36 in. (91.4 cm). Cleveland Museum of Art; Leonard C. Hannah fund, 1970.67.

This portrait of the Zen monk, Shinchi Kakushin (1203–1298), was likely created around the time of his death. Three other sculptural portraits of the monk are known in Japan, one of which contained a number of interior deposits. Owing to the now missing surface decoration, the joined-woodblock construc-tion method is visible in this work.

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

8 9

cat. nos. 2, 3, and 4), and Zen’en (1197–1258; see cat nos. 7 and 8) were awarded successive honorary ecclesiastical titles; the inclusion of these titles in documents and inscriptions can help to date Kamakura works with precision.12 Sculpture workshops were often family-based, with sons succeeding their fathers in the position of workshop head. The essay by Samuel C. Morse in this volume discusses the importance of lineage and the development of the Kei school (as the descendants of the sculptor Kokei [active 1152–1196], including Unkei and Kaikei, came to be known) in Kamakura sculpture. As Morse explains, a growing sense of individual artistic identity in the period is an import-ant reason for the increase in signed works. Another factor contributing to this practice is that sculptors were also followers of Buddhism, and the inscriptions perhaps served a devotional—in addition to a documentary—purpose. A person could gain much merit from creating an image of the Buddha, and the artist’s signature on the work established a permanent, tangible bond with the deity, to be discussed below.

In terms of stylistic influences on the naturalism of Kamakura sculpture, two factors loom large: sculptors looking backward in time and looking outward in geography. Within Japan, sculptors active in the Nara region were employed to replace and restore the statuary for the great temples of Kofukuji and Todaiji. Consequently, they attuned themselves to Nara-period sculpture displaying a high degree of naturalism, and per-haps sought to emulate this style in re-creating imagery for these temples. (The sculp-ture of the long intervening Heian period, by contrast, tends to be more idealized, abstracted, and otherworldly seeming.) Expanded contact with Song-dynasty China also played a role in stylistic change, as Chinese sculpture of that period displayed increased realism in form, proportion, and color. Because few artists had the opportunity to travel to China and limited quantities of Song sculpture were imported, much of the Song influence upon Japanese sculptors likely came through two-dimensional works of art. Records indicate that Kaikei made direct reference to Song-dynasty paintings in creating the Amida triad at Jodoji.13 Characteristics in Kamakura sculpture that point to Song antecedents are high, elegant topknots, fluttering hems of sleeves and robes, and long fingernails—all elements that well adapt from two-dimensional to three-dimensional forms. The early fourteenth-century Monju from the Philadelphia Museum of Art (see cat. no. 10) exhibits many of these Song traits, showing that they entered the stylistic vocabulary of Japanese sculptors and remained there after contact with China was inter-rupted in the late thirteenth century.

Technical developments in sculpture of the late Heian period, deployed on a wide scale in the Kamakura period, also contributed to the increased realism of these works. The technique of joined-wood-block construction ( yosegi zukuri ), in which multiple blocks of wood are carved separately and then assembled together to form a single statue, allowed for large works that could realistically express dynamic movement. This process created spacious, hollow interiors of sculptures into which consecrated objects could be inserted. A third section of the exhibition and the essay by Nedachi Kensuke in this volume consider this aspect of their devotional potency. The joined-block technique also allowed multiple craftspeople to work on a single sculpture simultaneously and produce images quickly in assembly-line fashion. This must have been especially conve-nient for the large sculptural output needed to replace works lost to fire and war.

One of the most dramatic technical developments in Kamakura-period sculpture was the use of rock-crystal or glass inserts ( gyokugan) for the eyes of sculptures, as seen on many works in this exhibition (fig. 3). As Samuel Morse explains in his essay, the

Enlivened Images

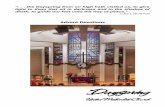

FIGURE 3. Head of a Guardian King. Kamakura period, 13th century. Polychromed Japanese cypress (hinoki) with lacquer on cloth, inlaid crystal eyes, and filigree metal crown. H. 221⁄16 x W. 10¼ x D. 1315⁄16 in. (56 x 26 x 35.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alastair B. Martin, the Guennol Collection, 86.21 (cat. no. 1).

This large head, once owned by Kofukuji Temple in Nara, exemplifies the expressive realism of Kamakura sculpture. The inset eyes are made of rock crystal and painted on the reverse for a life-like appearance.

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

10 11

Although large and luxuriously produced images could certainly serve the function of a private devotional image ( jibutsu), most personal icons were smaller in size and might be contained within a shrine (zushi ), just as a temple hall and altar house a larger image. The diminutive images in this catalogue and exhibition likely functioned in this context and give some sense of the breadth of objects of devotion in the period. Nyoirin Kannon (see cat. no. 31) and Aizen (see cat. no. 32) were popular esoteric icons wor-shipped for their ability to grant wishes and bestow benefits. Others maintained faith in Miroku (see cat. no. 33), the Buddha-to-be, who waits in his paradise while the Buddhist law declines and disappears, only then appearing in this world to precipitate a new golden age.

Even if enlivened through ritual performance, sculptures usually remained static on altars or in shrines. On occasion, however, images might be quite literally made to move through ritual processions or re-enactments. The ceremony of the welcoming descent of Amida (mukaeko) is performed even today at certain temples, most famously Taimadera in Nara.20 Historical records indicate that in the Kamakura period, monks wearing masks and costumes of bodhisattvas would parade to re-enact the welcoming descent. The sculptor Kaikei produced an over-six-feet-tall, half-nude statue of the Buddha Amida that would have been clothed and wheeled in a cart through this procession; Kaikei and other sculptors also produced a set of twenty-seven masks for the same temple.21 A bodhisattva mask (see cat. no. 27) might have been used in a similar ceremony, and the dramatic-looking tsuina mask (see cat. no. 28) would have been worn in fire-filled rituals as part of New Year’s ceremonies to chase away demons and ensure good fortune in the coming year. As the same workshops that created regular icons also carved such masks, there are stylistic affinities between masks and full-body sculpture of the period.

Less tangibly, icons were enlivened through legends, stories, visions, and dreams. The compilations of miracle tales that circulated in the late Heian and Kamakura periods are replete with stories of devotees whose personal devotional icons, or an icon at a temple they had traveled as pilgrims to worship, come to life and address the believer. Even unseen images could be accessed in this way, as these stories and experiences

inserts greatly enhanced the sense of lively presence of these works as the firelight reflected off the glass eyes in temple interiors.14 The eyes of an image also have a sym-bolic significance. The ritual for consecrating—and thus activating or enlivening—a Bud-dhist image is called the “eye opening ceremony” (kaigen kuyo), during which a priest ceremonially dots in the pupils of the eyes of the sculpture.15 Although ceremonial con-secration would be performed for various images, not just sculpture with crystal inserts, it indicates that the eyes were critical, both formally and ritually, to enlivenment.

ritual and devotional contextsThese sculptures were meant to embody the deity and effect its presence in ritual and devotional worship. Although many texts contain doctrinal discussions about the rela-tionship between the material, physical icon and the ultimately formless Buddha, Robert Sharf has remarked that devotees do not distinguish between the deity and its iconic form, and that even separate images of the same deity are endowed with unique, individual identities.16 In the ritual arena or in devotional worship, these individual icons mediate a communion between the divine and the human, whether to bring about spiritual awakening, to produce worldly benefits ( genze riyaku), or to ensure salvation in the afterlife.

Images of Daiitoku Myoo (see cat. no. 14) and Fudo Myoo (see cat. no. 15), both of which represent Wisdom Kings (myoo), are fierce deities in the esoteric Buddhist pantheon worshipped for their powers to remove obstacles to enlightenment and to bestow worldly benefits. Esoteric rites begin with the installation of the icon or group of icons on an altar. The rituals follow a process of purification of the space, making offer-ings to and welcoming the deity’s presence, chanting of scripture or mantras, manipula-tion of ritual implements (such as those also displayed in “Ritual and Devotional Contexts”), and, finally, sending off the deity in a manner analogous to seeing out an esteemed guest.17 The icon is temporarily “activated” when inhabited by the deity addressed through ritual. The ritual aims to unite the practitioner and deity, allowing divine insight and powers to be transferred to the practitioner, and by extension, to patrons of the rite. In the Kamakura period, temples and sculpture projects associated with esoteric rituals were sponsored by aristocratic and military patrons alike.

While such rituals could only be conducted by specialists initiated into the teach-ings and practices, popular worship of deities originally associated with esoteric forms, such as Nyoirin Kannon (see cat. nos. 16 and 31) and Bato Kannon (see cat. no. 30), also flourished. Bernard Faure has commented that the intensity of the worshipper’s faith is equal to the “ritual identification” of the officiating priest.18 Devotees formed “spiritual bonds,” called kechien, with icons and their associated deities as part of devotional prac-tice, through donations to image-making projects and inclusion of their names on lists or inscriptions of the dedication vow placed inside or inscribed on images. Devotional cults focused on individual deities, such as the historical Buddha Shakyamuni (see cat. no. 4), Prince Shotoku (see cat. no. 38), or the bodhisattva Jizo (see cat. nos. 2, 7, and 34), also increased in popularity. New forms of icons developed to meet the needs of believers. The standing Amida (see cat. no. 25), for example, contrasts with seated types prevalent earlier, and implies an active presence of the deity, moving forward to greet the devotee. Records describe people on their deathbeds holding cords attached to such images, establishing a physical connection between worshipper and icon, and by extension Amida Buddha.19 Such practices can occasionally still be found in temples today.

FIGURE 4. View of main altar of Tako Yakushido, Eifukuji Temple, Kyoto. Photograph courtesy of Mark Schumacher.

This image shows icons arranged on the altar of a temple hall, including offering stands and adorn-ments. Two icons of Yakushi Buddha are in the center, flanked by bodhisattvas, and the twelve divine generals. Note the five-colored rope that extends from the hand of the rear-center icon up and over the altar platform for the worshipper to grasp. The main icon of worship at this temple is a hidden (hibutsu) stone image of the Buddha Yakushi concealed in a shrine behind the two visible icons in front. The legend about this hidden statue states that it was a miraculous replica of another famous image, and was found by a monk in 1181 following a dream revelation in which the original icon appeared and spoke to the monk. See Yui Suzuki, Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 127.

Enlivened ImagesIve Covaci

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

12 13

within a large statue of the same Buddha at the temple Joruriji. These items and lists of names, like the rituals discussed above, represent another mode of “meeting” of devo-tee and deity that essentially takes place inside the work itself, where the embodied presence and its worshippers stand in a kind of permanent interaction.

Some specific Buddha images were considered especially capable of producing miracles and responding to devotees, and were referred to as “miraculous Buddhas” (reigenbutsu) or “living Buddhas” (shojinbutsu). Copies of these famous icons, such as the small bronze Amida triad of the Zenkoji type (see cat. no. 37 and the essay by Nedachi Kensuke in this volume), flourished in the Kamakura period. The replicas were consid-ered to partake in the essence of the original, itself often an unseen or hidden Buddha image, and helped spread the cults of specific, local manifestations of deities throughout the land.29 The prime example of such a living Buddha is perhaps the image of Shakya-muni enshrined at Seiryoji temple (see fig. 1 in Nedachi Kensuke’s essay and his discus-sion). Legends about this statue relate that it is a replica of, or in some accounts the original, sandalwood image commissioned by an Indian king to stand in for the Buddha while he ascended to the heavens to preach to his late mother. Upon the Buddha’s return to this world, the statue became animated and rose to greet the Buddha, who addressed the image, saying that it would aid in the spread of the Buddhist teachings after his death. Through such legends, Japanese devotees traced the existence of “enlivened” images capable of acting in the world back to the time of the historical Buddha himself.

This catalogue and the accompanying exhibition combine to take us on a journey from the arresting form of Kamakura-period works, through their function in ritual and devotional worship, and into their hidden interiors packed with spiritual significance. Overall, sculptures of this era exude a sense of humanness, brought about through artis-tic developments resulting in greater naturalism and approachability. Religious develop-ments of the time brought deities into closer proximity to their devotees and encouraged the “living presence” of icons.30 Long appreciated for their beauty and technical bril-liance, Kamakura sculptures must also be understood in this spiritual dimension, a dimension that encompassed the beliefs and practices of their artists, patrons, clerics, and devotees alike.

notes1 Epigraphs: The epigraph attributed to Myoe is taken from Robert Morrell’s translation of “Final

Injunctions of the Venerable Myoe of Toga-no-o” (Toga-no-o Myoe Shonin ikun) written in 1235 by Koshin, Myoe’s hagiographer. See Morrell, Early Kamakura Buddhism: A Minority Report, 60. The quote from Eison comes from a votive document for an icon of Monju. See David Quinter, “Votive Text for the Construction of the Hannyaji Mañjusri Bodhisattva Statue: A Translation of ‘Hannyaji Monju Bosatsu Zo Zoryu Ganmon,’ by Eison,” 472.

2 Mori Hisashi, for example, likens the sculptor Unkei (d. 1223) to Michelangelo, and Kaikei to Raphael. Mori Hisashi, Sculpture of the Kamakura Period, 108. The last major exhibition on Kamakura sculp-ture outside of Japan took place at the British Museum in 1991 and was entitled “Kamakura: The Renaissance of Japanese Sculpture.” See Victor Harris and Ken Matsushima, Kamakura: The Renais-sance of Japanese Sculpture 1185–1333.

3 For a discussion of the terms “icon” and its Japanese parallel honzon, or “principal object of worship,” see Robert H. Sharf, “On the Allure of Buddhist Relics,” 163–91. See also the concluding chapter in Donald McCallum, Zenkoji and its Icon: A Study in Medieval Japanese Religious Art, 179–94.

4 See, for example, the work of Helmut Brinker, Bernard Faure, Hank Glassman, Roger Goepper, Sarah Horton, Nedachi Kensuke, Samuel C. Morse, Oku Takeo, Robert Sharf, and Pei-Jung Wu listed in the bibliography to this volume.

allowed worshippers to interact with the many secret hidden images (hibutsu) of the period, which were displayed to devotees only on specific days, if at all (fig. 4).22

empowering interiorsIn the Kamakura period, adornment of the unseen interior by means of inscriptions and deposits was a primary way in which icons were “enlivened.”23 Advances in scientific techniques for examining the interiors of sculptures, such as X-rays, CAT scans, and endoscopic cameras, have led to the discovery of inscriptions and contents even when sculptures are not physically opened (fig. 5).24

A Bodhisattva Jizo (see cat. no. 34) is a rare example in western collections of a sculpture with intact contents, discovered during conservation treatment.25 Packed into this small image are miniature statues, scriptures, written incantations (dharani), printed sheets of thousands of tiny buddhas (inbutsu), and a silk bag with a grain considered to be a relic of the Buddha. Later in these pages, Nedachi Kensuke explains the logic by which such images are imbued with a numinous presence.

Although the practice of making deposits inside statues (zonai nonyuhin) was not new to the Kamakura period, several developments led to a dramatic increase in both the frequency and number of items deposited within sculptures. One is technical; as mentioned earlier, the joined-wood-block construction method allowed for larger hollow spaces within sculptures and thus accommodated many more contents. In some cases, special shelves or containers were fashioned within images to hold such objects in signifi-cant locations—for example, inside the head, in the center of the chest, or in the abdo-men. The small sculpture of the infant Shotoku Taishi (see cat. no. 38), while now devoid of contents, would likely originally have been filled just as other examples of its type.26

Another phenomenon that led to the increase in deposits within sculptures is the rise of relic worship in the Kamakura period.27 The legend accompanying representa-tions of the infant Shotoku relates that when the prince was two years old, he recited the name of the Buddha and a relic miraculously appeared within his palms. The sculptures of this type, widely created in the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, depict the prince with palms held together to imply the presence of this relic. The intent was to establish a strong parallel between the life of the legendary Japanese prince and the life of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni.28 The resurgence of devotion to the historical Buddha, whose corporeal presence in this world is signified by relics, also contributed to an increase in the practice of packing statues with sacred materials. When relics are deposited within a statue, the image becomes both a reliquary structure and the very body of the Buddha.

Other objects included in this section demonstrate devotional activities and the practice of forming “spiritual bonds” (kechien) with icons and deities, another important reason for the increase in deposits and inscriptions in sculptures. Commissioning or simply donating funds toward the production of a Buddha image generates merit for the patron. Therefore, sculptures were often accompanied by dedicatory texts including the names of the individuals who participated in the project, and—increasingly in the Kama-kura period—long lists of people, living or dead, to whom the donors wanted to extend the spiritual benefits of the image’s creation. Of course, the physical replication of a Buddha image or the copying out of a Buddhist scripture generates merit as well, and the results of such devotional acts could be placed into statues. A sheet of multiple printed images of Amida (see cat. no. 35) is one of many such sheets recovered from

Enlivened ImagesIve Covaci

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

14 15

24 (placeholder note about Shotoku if something is found through examination) 25 Since the discovery of its interior contents in 1983, when the statue was examined for conservation,

it has been the subject of numerous studies in German, Japanese, and English. See the entry for cat. no. 34. In English, the most recent study is the posthumously published article by Helmut Brinker, “Anointing with Eyes, Raiment, and Relic: Insights from the Cologne Jizo.”

26 For an analysis of the contents of another image of this type, see John M. Rosenfield, “The Sedgwick Statue of the Infant Shotoku Taishi.”

27 On relic worship, see Brian D. Ruppert, Jewel in the Ashes: Buddha Relics and Power in Early Medi-eval Japan.

28 See Kevin Gray Carr, “Pieces of Princes: Personalized Relics in Medieval Japan.” 29 For a study of these replicas, see McCallum, Zenkoji and its Icon.30 Robert Sharf states, “Japanese Buddhist icons were, more often than not, regarded as living pres-

ences. . . . This conclusion is simply inescapable: it is reiterated in historical documents, in liturgical and ritual materials, in biographies, hagiographies, and mythology, and is fully countenanced by scripture and commentary.” Robert H. Sharf, “Prolegomenon to the Study of Japanese Buddhist Icons,” 8.

5 For a more in-depth historical overview of the Kamakura period, see the essays by Andrew Goble and Ethan Segal, in Japan Emerging: Premodern History to 1850.

6 Recent scholarship on Heian-period Japan has revised the notion that this period was altogether insular. While formal diplomatic exchange ended, it is now clear that commercial and religious exchange continued to occur throughout the period, serving also as channels for informal diplomacy. See Adolphson, Kamens, and Matsumoto, eds., Heian Japan: Centers and Peripheries.

7 For an in-depth account of this rebuilding and Chogen’s role in it, see John M. Rosenfield, Portraits of Chogen: The Transformation of Buddhist Art in Early Medieval Japan, 97–127.

8 Unfortunately, this work is too fragile to be considered for travel to this exhibition.9 Scholarship on this issue as it pertains to the Zen context includes Bernard Faure, Rhetoric of Imme-

diacy: A Cultural Critique of Chan/Zen Buddhism and Visions of Power: Imagining Medieval Japa-nese Buddhism; Helmut Brinker and Hiroshi Kanazawa, Zen Masters of Meditation in Images and Writings; and Gregory P. A. Levine, Daitokuji: The Visual Cultures of a Zen Monastery.

10 William M. Bodiford, “The Medieval Period: Eleventh to Sixteenth Centuries,” in Nanzan Guide to Japanese Religions, 165. This essay provides a succinct overview of recent scholarship on medieval Japanese Buddhism.

11 Recent discussions of sculptural realism in the Kamakura period in English include Rosenfield, Por-traits of Chogen, and Samuel C. Morse, “Animating the Image: Buddhist Portrait Sculpture of the Kamakura Period.” Morse argues that the realism of the period is not merely due to technical and stylistic developments, rather it was a result of a new emphasis on understanding Buddhahood as originally existing in all beings (hongaku shiso). He writes, “The adoption of a naturalistic mode of figuration by the sculptors of the Kamakura period was a clearly articulated ideological choice derived from the conviction that the potential for salvation resided in all phenomena,” 27–29.

12 These are hokkyo (“bridge of the law”), hogen (“eye of the law”), and hoin (“seal of the law”), the last being the most exalted.

13 Yoshiko Kainuma, “Chogen’s Jodoji Amida Triad and its Environment: A Theatrical Effect of the Raigo Form,” 110.

14 The earliest extant example of the use of gyokugan is in the Amida Triad at Chogakuji which dates to 1151 (see fig. 1 in Samuel C. Morse’s essay in this volume).

15 Conversely, when an icon requires restoration work, monks must first perform a ceremony to remove the “spirit” so that sculptors can work on the inanimate object. See Fabio Rambelli, “Secret Buddhas (Hibutsu): The Limits of Buddhist Representation,” 285.

16 Sharf, “On the Allure of Buddhist Relics,” 172.17 For a recent study of esoteric ritual, see Koichi Shinohara, Spells, Images, and Mandalas: Tracing the

Evolution of Esoteric Buddhist Rituals.18 Faure, Visions of Power, 258.19 On this practice see Sarah Horton, “Mukaeko: Practice for the Deathbed,” 27–44, and Sarah Horton,

Living Buddhist Statues in Early Medieval and Modern Japan, 70–73.20 For a description of the contemporary ritual, see Horton, Living Buddhist Statues, 52–53. For a

historical study, see Horton, “Mukaeko: Practice for the Deathbed.”21 A comprehensive study of these masks is by Furuhata Noriko, “Hyogo Jodoji bosatsumen no seisaku-

sha to zozo haikei: Kaikei, mukaeko, shojin shinko.” See also Rosenfield, Portraits of Chogen, 160–61.

22 On these, see Rambelli, “Secret Buddhas (Hibutsu),” 271–307.23 For recent work on interior deposits, see the following: Helmut Brinker, Secrets of the Sacred:

Empowering Buddhist Images in Clear, in Code, and in Cache; Samuel C. Morse, “Revealing the Unseen: The Master Sculptor Unkei and the Meaning of Dedicatory Objects in Kamakura-Period Sculpture”; and Pei-Jung Wu, “Wooden Statues as Living Bodies: Deciphering the Meanings of the Deposits within Two Mañjusri Images of the Saidaiji Order.”

Enlivened ImagesIve Covaci

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

16 17

SOFTENING THEIR LIGHT, MINGLING WITH THE DUSTJAPANESE GODS IN BUDDHIST ART

Detail of cat. XX (see page XX)

Hank Glassman

Gazing at the images and objects gathered in this catalogue and the exhibition it accom-panies, one cannot help but be struck by their immediacy and raw power. While the modern viewer finds in their beautifully composed surfaces, lines, and shapes breathtaking technical mastery and aesthetic force, the transcendence of these images is evident even to the casual observer fully rooted in the modern world of the real. For those who com-missioned their creation, the power of these works was of a different order all together. Imbued as they are with the prayers and magical intentions of their makers and those who worshipped and treasured them over centuries, they speak to us across the historical and cultural divide with a profound eloquence. This essay seeks only to amplify and gloss this speech; translation remains unnecessary in the wordless communion.

It might behoove us to stretch somewhat to imagine the full engagement of the sensorium: a large wooden hall echoes with the rhythmic chanting of monks; the air fills with the heady fragrance of incense pressed from sandalwood, agarwood, and camphor; and numerous oil lamps and candles flicker, set in their heavy iron bases. We can envi-sion the crystal eyes ( gyokugan) of the statues glittering in flashes of candlelight and the golden gleam of the ritual implements as the monks move them with practiced solem-nity and grace. The objects gathered here in the galleries and between the covers of this book are first and foremost the focus of religious devotion; their great beauty is undeni-able and must also be understood as an essential aspect of their efficacy. Yet, these images and objects were made splendid not only to draw the eye. Far from inert and passive objects of aesthetic admiration, these are “real presences” (a phrase from Robert Campany), fashioned with great care and cost for the purpose of bringing about con-crete changes both in the worshipper and in the external world. They come to us as fragments of an integrated and complex system of devotion. Though removed from their original contexts, many contain clues and indicators to help us imagine more fully their place in the religious regimes of the day.

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

18 19

What were the contours and concerns of the religious tradition that produced these sculptures, paintings, masks, and ritual implements? What do the artifacts reveal about the spiritual life, worldview, and religious imagination of Kamakura-period Japan?

ECLECTICISM AND COMBINATORY FAITH: RELIGIOUS TRADITIONS IN THE KAMAKURA PERIOD

The Kamakura period (1185–1333), as Ive Covaci explains in her introduction to this volume, was a time of great foment and religious innovation. Political turmoil, natural disasters, and a millenarian sensibility all spurred on an energetic phase of building and consolidation. Here, I refer not only to the construction of physical edifices and the solid-ification of institutional structures; there were also substantial doctrinal, ritual, and artis-tic advances. During the Heian period (794–1185), Buddhism had come to play a fundamental role in court culture and in political discourse. Key temples had grown extremely influential, as had a general Buddhist worldview.

The cosmology of Buddhism, a foreign religion imported to Japan from the main-land in the sixth century CE, had become widespread as a sort of common sense. Ideas of rebirth through the cycle of samsara and karmic reward and retribution, as well as a hope of salvation through the intervention of compassionate buddhas and bodhisattvas, were by now well known to all within the ken of Japanese civilization. Down through centuries, the creativity and industry of preaching monks, collectors of miracle accounts, painters, and sculptors wove together various strands from India, China, Korea, and Japan to create a convincing tapestry of belief.

A very complexly articulated vision of Buddhism, one deeply colored by so-called Tantric or Esoteric ideas and practices, had arisen among the clerics, patrons, and elite artisans who created the objects and icons gathered in this exhibition and book. Esoteric Buddhism (mikkyo in Japanese) is a system or style of religion imported from China to Japan in the mid-Heian period, not too long after it had come from India to China.1 Esoteric Buddhism, also called Vajrayana or Mantrayana (Shingon) Buddhism, dazzles the eye and occupies the mind with a large and varied pantheon of wrathful and peaceful deities, an array of ritual implements, and dramatic ceremonies. This form of the Mahayana emphasizes the inherently enlightened nature of all beings and insists upon the full engage-ment of the senses, rather than a retreat from them. According to this line of thinking, by filling body, speech, and mind with the sights and sounds of the transcendent bud-dhas, a person transforms the mind to erase the effects of habitual thinking. Every item appearing in this exhibition was created with this ultimate intent: to capture the human mind and propel it in the direction of awakening to its own originally pristine nature.

This era also saw the deepening of an already established system of correspon-dence between the pantheon of Buddhism and the native Shinto gods, or kami. That is, as was typical of Buddhism in many cultural contexts, rather than conquer or obliterate the old gods, the imported religion placed an emphasis on the assimilation of the Japa-nese gods, or kami, to Buddhist deities. This meant that equivalencies were proposed between certain buddhas and bodhisattvas, on the one hand, and certain Shinto kami, on the other. The practice or theory of combining buddhas and kami was termed honji suijaku (original ground and trace manifestation); this means the kami are viewed as local manifestations of the Buddhist deities. The Shinto gods, in many cases deified ancestors of aristocratic families, continued to hold a very important position in the reli-

Hank Glassman

gious life of people in Japan even as the power and influence of Buddhism rose. In a common phrase of the time, the buddhas and celestial bodhisattvas “soften their light and mingle with the dust,” condescending to take form as more approachable kami and bending to Japanese custom in order to better minister to the people of that land. Along with this rapprochement between Shinto and Buddhism, the period saw techno-logical and artistic innovations that gave rich visual expression to these theological nego-tiations and collaborations.

EMPOWERING IMAGES

The most relevant of those innovations for the present exhibition is no doubt the devel-opment of new sculptural techniques that allowed carvers to bring to these icons a striking sense of optical reality. As Sherman E. Lee (1918–2008), an important advisor to many of the collections represented in this exhibition, put it, “Once images were no longer confined to single large columns of wood, the sculptor could indulge in more daring explorations of the volumes, voids, and drapery. Limbs and hands became more active and expressive.”2 As Covaci points out, the new fitted-wood technique also opened up interior spaces, where clerics, sculptors, and ritual specialists worked to create a differ-ent verisimilitude through tantric magic.3 A wide array of items and inscriptions have been discovered inside statues of the period: scriptural texts on paper, relics in small pagodas, votive statements, smaller sculptures, magical Sanskrit spells and syllables painted on the interior surfaces, even internal organs sewn together of different types of wadded silk cloth. In his essay for this volume, Samuel C. Morse discusses how the crystal eyes inset in the statues’ heads are essential to their almost eerie realism. Interior spaces were often used to illustrate and articulate the connections between the kami and the buddhas. As carefully wrought and exquisitely finished as the exteriors are—and of course we can scarcely imagine what they would have looked like colorfully painted and gilded—it is the doctrinal and mantric manipulations within these invisible interior spaces that empower the icons.

BUDDHAS AND KAMI: ESTABLISHING IDENTITY

The doctrine of honji suijaku held that the buddhas and bodhisattvas manifested as Japanese gods to facilitate connection. It is one thing to state this as a theory and another to develop it into a convincing theological tenet. In this task, artistic inven-tion and ritual innovation were essential. As the belief in a combinatory vision of Buddhism and the local Shinto traditions continued to deepen over the course of the twelfth century, clerics and the artisans who worked with them became increasingly interested in representing this relationship between the imported deities and the local in concrete ways.

Two small statues by Zen’en representing the bodhisattvas Jizo and Monju illustrate this process especially well (see cat. nos. 7 and 8). These diminutive figures are remark-ably well preserved and, within their perfect proportions, these jewel-like pieces have a fascinating “inside” story to tell us. The Jizo from the Asia Society Museum Collection (cat. no. 7) and the Monju from the Tokyo National Museum (cat. no. 8), along with an eleven-headed Kannon image held by the Nara National Museum (fig. 1) were almost certainly originally from a set of five carved by Zen’en.4 These images were

Softening their Light, Mingling with the Dust

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

20 21Hank Glassman

FIGURE 1. Standing Eleven- headed Kannon by Zen’en. 1221. Collection of Nara National Museum, (object no. 803-1).

created in order to represent the kami of the Kasuga shrine—an ancestral shrine to the powerful Fujiwara family—in their Buddhist guises. The four old Kasuga gods, and a fifth young god, or wakamiya, added in the twelfth century, each had a Buddhist alter ego. The new god, or young lord, is portrayed as Manjusri (Monju bosatsu), here a beautiful child with the five knots of wisdom for his coiffure. The Jizo image embodies the deity Amenokoyane, the main Kasuga god and progenitor claimed by the Fujiwara clan.5 The other two images, now lost, presumably represented Shakyamuni Buddha and Yakushi, the medicine Buddha, as they would complete the set of five Kasuga “original manifes-tations,” honji.

These images, created in the early years of the thirteenth century, dedicated and enlivened with the prayers of clerics and patrons, represent the Buddhist “original ground” to the “trace manifestations” of the five kami of Kasuga. The interiors of the three extant statues reveal a great deal about the social and ritual contexts for their cre-ation and dedication. Their inside surfaces are completely covered with prayers and spells, most remarkably with the Sanskrit seed character, or bija of the deity in question, written one thousand times. Among the votive prayers and various dharani spells and mantras, we also find the names of high-ranking monks, nuns, and lay aristocrats listed, tying them to the karmic benefits generated in the production of the images.

The gods of the Kasuga shrine were a common cultic focus of the monks of Kofukiji, the temple that formed a single complex with Kasuga. Many paintings of the famous shrine in Nara represent the landscape of the giant temple-shrine complex and the “orig-inal manifestations,” Buddhist honji, of the Kasuga deities floating above Mount Mikasa (fig. 4).

The style of worship developed at Kofukuji and Todaiji was very influential on the material and visual culture of the nearby temple Saidaiji in the same city of Nara, the old capital. As much as the six so-called Southern Capital sects emphasized the sameness of the kami and the buddhas, and as much as they integrated and developed tantric tech-niques and motifs into their regimens, liturgies, and repertoires, the schools also nour-ished a fervent devotion to Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha. This faith is evident in the beautiful Standing Shaka Buddha by Kaikei in the Kimbell Museum and Shaka Nyorai in the Rietberg Museum (see cat. nos. 4 and 29), as well as in the many related objects and reliquaries that were also created, specifically those shaped as pagodas—not the great architectural towers with gabled roofs, which always do house relics, rather various miniature analogues of the stupa, the grave mound of the Buddha himself.

PAGODAS, WISHING JEWELS, RELICS, ICONS: THE SEED OF THE SACRED

Particularly striking among the objects in the exhibition and catalogue are the various small pagodas: among them, the ones held by the two Bishamonten images as icono-graphical attributes (see cat. nos. 6 and 39); the dark wooden reliquary (see cat. no. 41); the one that forms the finial of the gilt-bronze bell (see cat. no. 18); and the reliquary carved from quartz crystal (see cat. no. 40).6 From the earliest days of Buddhism, back to the very first records and established sites of worship, the cult of relics has been a central part of Buddhist practice. The relics are not bone fragments, as often seen in the Latin West, but are cremated remains that have undergone miraculous transformation into smooth pearlescent grains of five colors. In Buddhist iconography, relics are often

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

22 23

represented as flaming jewels, and sometimes as treasures piled together, such as on an unusual vajra in the exhibition (see cat. no. 21). The wishing jewel, or cintamani (nyoi hoju in Japanese), the same jewel held by Jizo or Nyoirin Kannon, is a magical object, closely associated with the relics of the Buddha. The pinnacle of the five-tiered reliquary pagoda just mentioned takes the shape of the mani jewel. Buddha relics placed inside a statue would be encased in a glass or gemstone sphere that was in turn enshrined within a pagoda-shaped reliquary, nested within each other like Russian dolls. These reliquar-ies, invisible once housed in the image, offer us an important reminder. The objects, beautiful though they are, have a power far beyond their sublime form or attractive proportions. As with the thousand siddham letters adorning the interior surface of the Zen’en Jizo, they are the very stuff that brings the icon to life.

notes1 For insightful explorations of the doctrinal, cultural, textual, and visual world of Esoteric Buddhism

in ninth-century Japan, see Ryuichi Abe, The Weaving of Mantra: Kukai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse, 1999; and Cynthea J. Bogel, With a Single Glance: Buddhist Icon and Early Mikkyo Vision, 2009.

2 Sherman E. Lee, Reflections of Reality in Japanese Art, 1983, 90.3 I borrow the heading for this section from a volume by Helmut Brinker that is a sophisticated and

lucid investigation of the practice of inserting prayers and objects into the bodies of Buddhist statues in Japan. In Brinker’s phrase, this transforms the statue “from image to icon.” Helmut Brinker, Secrets of the Sacred: Empowering Buddhist Images in Clear, in Code, and in Cache, 2011. A great deal has been written on the topic of animating images in a number of different Buddhist cultural contexts. For another in English, see James Robson, “The Buddhist Image Inside Out: On the Placing of Objects Inside Statues in East Asia,” in Buddhism Across Asia: Networks of Material, Intellectual and Cul-tural Exchange, vol. 1, edited by Tansen Sen, 2009.

4 For more on this set of images, see Sherry Dianne Fowler, “Between Six and Thirty-three: Manifes-tations of Kannon in Japan,” in Kannon, Divine Compassion: Early Buddhist Art from Japan (English edition of Kannon: Göttliches Mitgefühl, frühe buddhistische Kunst aus Japan), 2007. On Saidaiji’s Eison and his collaboration with Zen’en, also see Paul Groner, “Icons and Relics in Eison’s Religious Activities,” in Living Images: Japanese Buddhist Icons in Context, 2001.

5 On this image and the related “nude” Jizo at Denkoji in Nara, see chapter 2 of Hank Glassman, The Face of Jizo: Image and Cult in Medieval Japanese Buddhism, 2012.

6 On the topic of reliquaries and other relic implements, such as the vajras from the collections of John C. Weber and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in this volume and exhibition, see chapter 8 of John M. Rosenfield, Portraits of Chogen: The Transformation of Buddhist Art in Early Medieval Japan, 2011.

Softening their Light, Mingling with the Dust

FIGURE 4. Kasuga Shrine Mandala. Kamakura period, late 13th century. Hanging scroll; ink, color, and gold on silk. H. 39½ x W. 155⁄8 in. (100.3 x 39.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, credit and acc number tk.

placeholder image

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

CATALOGUEIve Covaci and D. Max MoermanCopyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

28 Catalogue

The deep carving and expressive realism of this head exemplify Kamakura sculptures of fierce deities, and traces of original brightly painted polychromy remain on the surface. The head once belonged to Kofukuji, one of the Nara temples that lay at the center of the revival of realism in sculpture of the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries. The heads of statues were often worked on separately and then placed onto the body of the sculpture. As seen here, one of the technical innovations developed in Nara-area sculpture workshops that allowed for a sense of life-like presence in Kamakura sculpture was the use of inset crystal eyes that caught and reflected candlelight in dark temple interiors. The crystal would be inserted into the eye opening from within the hollowed-out head, which in this work is made of two separate pieces, with an additional piece for the topknot (the filigree crown is a later replacement). The crystal was painted on the reverse to show pupils and irises, backed with white paper, and then held in place with a small wooden panel secured by wood nails.IC

Kamakura period, 13th century Polychromed Japanese cypress (hinoki ) with lacquer on cloth, inlaid crystal eyes, and filigree metal crown H. 221⁄16 x W. 10¼ x D. 13 15/16 in. (56 x 26 x 35.5 cm)Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alastair B. Martin, the Guennol Collection, 86.21

This over-life-size head with ferocious expression sur-mounted a large, dynamically posed sculpture of an armor-clad guardian king trampling a demon. Pairs of such images could serve as guardians at either side of a temple gate or as a group of Four Heavenly Kings (Shitenno) they could occupy the four corners of the central altar of a hall. Each guardian king is associated with one of the cardinal directions and serves to protect the Buddhist Law and the Buddha enshrined within the hall. The Four Heavenly Kings were invoked in rituals for the protection of the state in Japan since the Nara period, and enjoyed a resurgence in popularity with the threat of the Mongol invasions in the late thirteenth century.

1

HEAD OF A GUARDIAN KING

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

30 Catalogue

1 Miyeko Murase, Bridge of Dreams, 70–73.2 On the relationship between Kaikei and Chogen, see John M. Rosenfield, Portraits of Chogen.3 Murase, Bridge of Dreams, 73.4 Samuel C. Morse, “Kaikei-saku Jizo Bosatsu ryuzo / Standing Image of Ksitigarba by Kaikei,” 24.

in the first decade of the thirteenth century that were widely imitated by other sculptors in later years. The appeal of works in this style to the devotee is clearly understand-able, especially for images of the Buddha Amida, who promises rebirth in paradise, or for images of bodhisattvas such as Jizo, who promises salvation from the torments of hell and the other undesirable paths of rebirth.

Kaikei is not the only sculptor mentioned in the inscription. It also includes the names of two of his associ-ates, En’Amidabutsu Shinkai and Ryo’Amidabutsu.3 These names have also been found on other works by Kaikei, giving us insight into the organization and division of labor in sculpture workshops. En’Amidabutsu, who is likely the same person as Shinkai, seems to have been a specialist in making inset crystal eyes ( gyokugan) and may have been responsible for the ones on this image.4 The interior of this Jizo also contains the written Sanskrit “seed syllables” (bija) of Jizo, Amida (on the lotus), Dainichi (the cosmic Buddha at the center of the esoteric Diamond World Mandala), and the bodhisattva Fugen, reflecting the layering of identities and associations that such icons represent.IC

Kamakura period, ca. 1202Lacquered, polychromed, and gilded Japanese cypress (hinoki ) with cut gold leaf (kirikane) and inlaid crystal eyesH. 201⁄8 in. (51.2 cm); pedestal H. 17⁄8 in. (4.8 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015, TR.10.226.2015 (Burke storage number SC 17)

This small image of the bodhisattva Jizo is one of only three signed works by Kaikei in western collections.1 The statue can be dated to around 1202 based on the inscrip-tion on the interior, “An’Amidabutsu,” a signature that Kaikei used up until the year 1203 (fig. [interior]). Kaikei began to use this name while working closely with the monk Chogen (1121–1206), who similarly called himself “Namu Amidabutsu Chogen,” and whose followers often adopted these names as a reference to their faith in the Buddha Amida of the Western Pure Land.2 Kaikei’s works signed in this manner gave rise to the designation “An’Ami mode” characterized by the beautiful, refined, and somewhat idealized sculpture that Kaikei produced

2

KAIKEI (ACTIVE CA. 1183–1223) STANDING JIZO BOSATSU

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

34 Catalogue

1 Selected publications: Miyeko Murase, Bridge of Dreams, no. 22, 74–76; and Anne Nishimura Morse and Samuel C. Morse, eds., Object as Insight, no. 36, 94–95.

2 The eyes are later replacements, but the original would have had inset crystal eyes as well.3 Murase, Bridge of Dreams, 76.

naturalism and sense of muscularity, evident in the modeling of the chest and articulation of the waist in this figure. The expressive but not overly exaggerated face, with deep furrowed eyebrows and fleshy cheeks, also brings a greater sense of realism to the work. The crystal inset eyes ( gyokugan) would have reflected the light of the fire ritual ( goma) offerings to this deity and he would have been framed by a flame-shaped halo.2 Fudo is usually seated on a rock-shaped pedestal befitting his name’s meaning of “the immovable one.” The sword and the lasso he holds are later replacements but they represent the deity’s ability to cut through illusions and to bind the obstacles to enlightenment, pulling sentient beings onto the path of salvation.

It has been suggested that this sculpture came from the Tendai-school temple Shoren’in in Kyoto. In the early decades of the thirteenth century, Kaikei maintained a relationship with this temple and several of its aristocratic abbots.3 Although Kaikei is best known for his work in the Nara region with the monk Chogen (1121–1206), it should be remembered that he and other Kei-school sculptors also produced many works for Kyoto-based aristocracy and clergy.IC

Kamakura period, early 13th centuryLacquered, polychromed, and gilded Japanese cypress (hinoki ) with cut gold leaf (kirikane) and inlaid crystal eyesH. 20¼ in. (51.5 cm)The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015, TR.10.227.2015 (Burke storage number Sc 19)

This balanced yet fierce sculpture of Fudo, one of the Wisdom Kings (Myoo) in esoteric Shingon Buddhism, is one of very few works in western collections attributed to the early Kamakura-period master sculptor Kaikei.1 A temple in Kyoto, the Sanbo’in, holds a very similar image of Fudo signed by Kaikei and dated to 1203, which helps date the present unsigned statue to the early thirteenth century, as well. The folds of the drapery and the sense of breath-filled three-dimensionality are traits distinctive of this sculptor’s work.

Worshipped in Japan since the early Heian period, the traditional iconography of Fudo Myoo dictates his stocky, child-like body and scowling face. In the Kamakura period, however, depictions of Fudo were imbued with a new

3

KAIKEI (ACTIVE CA. 1183–1223) FUDO MYOO

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

36 Catalogue

1 Rosenfield, Portraits of Chogen, 139. See chapter seven of Rosenfield’s volume for a discussion of Kaikei’s oeuvre.2 Kaikei created a pair of standing statues of Amida and Shaka for the Kenkoin, a temple of the Pure Land sect.

On these, see Rosenfield, Portraits of Chogen, 149.3 In a recent article, Iwata Shigeki links this statue to Kasuga worship because of the Sanskrit characters corresponding

to the honjibutsu (“original trace manifestations”) of Kasuga on the halo, which he considers original to the work; others have postulated that the halo is a later addition to the statue. The pedestal, on the other hand, is likely not original to the work. Iwata Shigeki, “Standing Shaka Buddha by Kaikei from the Kimbell Art Museum Collection.”

style is characterized by naturalistic proportions, simplified but beautiful rendering of the drapery folds, idealized and refined expression in the face, and a gentle sense of movement. Like this work, the statues Kaikei produced in this style are often small, conforming to the standard measurement of approximately three feet (sanshaku). Shaka is fully covered in gold paint (kindei ) with further application of cut goldleaf patterns on the robe, creating a highly refined effect.

Revival of faith in the historical Buddha is an import-ant characteristic of Kamakura-period Buddhism, and images of Shaka took on an increasingly active presence in new iconographic formulations.2 Whether depicted standing in the “Welcoming descent of Shaka” (Shaka raigo), paired with Amida as “dual objects of veneration” (nison), or worshipped as one of the “original ground” (honji) of the Kasuga shrine as part of Shinto-Buddhist syncretism, these new forms of Shaka speak to the fertile combination of religious traditions in Kamakura Buddhist art.3

IC

Kamakura period, ca. 1210Gold-painted (kindei ) and lacquered wood with cut gold leaf (kirikane) and crystalH. 547⁄16 x W. 19¼ x D. 13½ in. (138.2 x 48.9 x 34.3 cm)Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas: AP 1984.01 a,b,c

This radiant statue of Shaka, the historical Buddha, is inscribed with the name of the sculptor Kaikei on the left-foot tenon. The inscription reads “Kosho hogen Kaikei,” in which kosho means “highly skilled craftsman” and hogen signifies “eye of the Law,” the middle of three ecclesiastical ranks awarded to sculptors. The signature helps date the work to around 1210, when Kaikei ascended to this rank.

As many as thirty-eight works by this master are extant, allowing art historians to trace the development of his style.1 This rare image of Shaka (only one other by Kaikei is known) closely resembles the much more numer-ous statues of the Buddha Amida created in the “An’ami mode,” so-called because Kaikei often signed these works with his religious name An’amidabutsu (cat. no. 2). This

4

KAIKEI (ACTIVE CA. 1183–1223) STANDING SHAKA BUDDHA

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

38 Catalogue

1 The ritual is described in Taiko Yamazaki, Shingon, 182–90.2 On this work, see Iwata Shigeki, “Suisu Ritoberugu Bijutsukan kizo bosatsu zazo” [The seated wooden bodhisattva

statue in the Rietberg Museum, Switzerland].

In contrast to the very human-looking devotional icons elsewhere in this section of the catalogue and exhibition, the straight-backed body position, spherical face, geometrically rendered facial features, and severe pattern in the draperies create a reserved appearance befitting the esoteric and cosmic nature of this deity. In these characteristics, this Kokuzo bears some resemblance to representations of Dainichi, the cosmic Buddha, by the sculptor Unkei (see fig. X in the essay by Samuel Morse in this volume). Lacking an inscription or date, the image has been attributed to the late-twelfth-century Kei school on the basis of style.2 The well-preserved statue has portions of the original black lacquer and white paint, and gold foil on the crown and robes. The towering hairstyle is in the Chinese Song-dynasty (960–1279) style, and there are remnants of attached cascading hair on the right shoulder of the figure. Auspicious Buddhist symbols are painted with red pigment onto the body of the figure: a swastika appears on the chest and the palms display the Wheel of the Law (dharmachakra).IC

Kamakura period, late 12th centuryWood with black lacquer, polychrome, and gilding H. 235⁄16 in. (59.2 cm)Museum Rietberg Zürich, Donated by Julius Müller, RJP 13

The name of the bodhisattva Kokuzo means “repository of the void” and symbolizes his unlimited wisdom and compassion. This form of the deity is associated with an esoteric rite called the Gumonjiho, or “Morning star meditation.” Performed since the Nara period, this wisdom- and memory-increasing ritual involves reciting the mantra of the bodhisattva one million times, and was popular among Kamakura-period monks combining practices from esoteric Shingon Buddhism with other traditions.1 Although many icons for this ritual survive as paintings, sculpted icons are lesser known. The size of this statue conforms to the iconographic prescriptions of the ritual, and the bodhisattva possibly held a lotus topped with a flaming jewel in his left hand, to accord with the wish-granting mudra made by the right hand.

5

KOKUZO BOSATSU

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

44 Catalogue

FIGURE XX. Plate 7 interior views

45Catalogue

Copyright @Yale University Press 2015 For marketing purposes only

46 Catalogue

1 On this work, see Yamamoto Tsutomu, “Tokyo Kokuritsu Hakubutsukan hokan Monju Bosatsu ryuzo / Manjusri (Standing Image).” See also Oku Takeo, “Nara no Kamakura jidai chokoku” [Nara sculpture of the Kamakura period].

2 See the essay by Hank Glassman in this volume.

each associated with one of the native deities (kami) enshrined there.2 Monju is usually represented seated, but in this case his standing posture may relate to his grouping with the other images in the set. Originally, he would have held a sword or lotus in his right hand and a scroll in his left; the hands are likely later replacements.