copyright. Research andthe general practitioner · manorial system was established in which the...

Transcript of copyright. Research andthe general practitioner · manorial system was established in which the...

1614 BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 295 19-26 DECEMBER 1987

Riding horses used to be a difficult skill. Saddles had been in usefor about 400 years, but they were simple, there were no stirrups,and to stay on you depended on the strength of your thighs. If youwere really expert you could use a bow. You could use a light lance,held with a bent arm, but any attempt to impale an opponent wouldpitch you over the tail of your own horse. Somewhere, probably inChina, a foot board was attached to the saddle that made ridingeasier, and the barefooted riders ofhot countries used a simple loopinto which they could stick their big toe. During the seventhcentury wooden stirrups appeared, and in 694 the Islamic generalal-Muhallab noted that these broke easily and ordered that they bemade of iron. This is the first reliable date in the whole sequence.

Foot soldiers versus armed riders with stirrupsIron stirrups properly secured to saddle made it possible for the

horseman to wield a sword without falling off and led to thedevelopment of the longsword. The horseman could carry aheavier lance, which soon developed into the mediaeval spear, heldfirmly so that on its point could be delivered the whole impetus ofhorse and rider. No footman could stand against the armed riderwith stirrups, and by 730 the writing was on the wall for those whostill depended on the mass levy of foot soldiers.But heavy horses, weapons, remounts, and armour were ex-

pensive. No one could buy these and at the same time maintainhimself in food. Charles Martel and his successors were benefactorsto the popes and managed to charge the church lands with the dutyof supplying these increasingly heavy cavalry. They did this byrelieving the soldier of the task of feeding himself and family byliving on the surplus value of several peasant families. So themanorial system was established in which the manor was largeenough to provide horse and remounts, horse furniture, spears,swords, and a servant to keep these in proper order, thus enablingthe soldier to spend his peaceful days in military exercises. The

three field system produced enough oats for his horses. There issome evidence that the children of such soldiers preferred to followthe military occupations, and it has been suggested that one of thecrusades was encouraged to rid western Europe of these quarrel-some and troublesome landless knights.But horse breeding for military horses produced heavy horses

unsuitable for war or too many for use as war horses. Mares andgeldings were useful for farm work, and by 890 Alfred wasexpressing surprise that horses were used for ploughing in Norway.So- the task of the ploughman was lightened and within a fewcenturies the outlying homestead was deserted and peasantscrowded into the village where they could find blacksmith, priest,fellowship, news, and a greater choice of girls and sons in law.The last invention seems to have been the iron horseshoe; hoofs

are sensitive when wet, and the iron horseshoe saved the hoof onrough soils and difficult journeys. They first appeared about 900 andby 970 were usual for all long journeys.

So by 1000 aLl the technical skills needed for the application ofhorse power to human needs were available, the essentials of thefeudal economy were in place, and "Man had been a part ofnature;now he became her exploiter."

ReferencesI Farrow SC. McKeown reawssd. BrMedJ 1987;294:1631-2.2 McKeown T. The modan rise ofpopuakion. London: Edward Arnold, 1976.3 White L Jr. Medievdaechssl axd social chane. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962.4 Lamb HH. Chmate, huy, and tke modem uworld. London and New York: Methuen 1982.

Haywards Heath, West Sussex RH16 1HHGEORGE DISCOMBE, MD, FRCPATH, retired consultant pathologistCorrespondence to: Highwood, 10 Paddockhall Road, Haywards Heath, WestSussex RH16 IHH.

Research and the general practitioner

CHRISTOPHER C BOOTH

"Know then thyself, presume not God to scan,The proper study ofMankind is Man."

Pope

The Provincial Medical and Surgical Association, the parent bodyof the present British Medical Association, was founded in 1832. Itis significant that the BMA owes its origins not to city practitionersin London but to a group ofprovincial doctors who believed that theprovincial practitioner had as much to offer in the study ofdisease ashis counterpart in the metropolis. The foundation year was onlynine years after the death of Edward Jenner, so that the foundershad before them the shining example of a unique scientificachievement made by a country practitioner working in the hills andvalleys of his native Gloucestershire.There were during the nineteenth century in England other

country practitioners whose discoveries were to make a majorcontribution to the advance of medical knowledge. William Budd,working as a country doctor in his native village ofNorth Tawton inDevonshire in the 1830s, established that typhoid fever was acommunicable disease and that it was due to an infectious agent thatcould be transmitted by contaminated water from one patient toanother.' In 1841 he moved to practise in Bristol and became anactive member of the fledgling Provincial Medical and SurgicalAssociation. There in 1866, following in the steps ofJohn Snow, he

showed how a cholera epidemic in the city could be controlledby hygienic measures. William Budd pointed to the particularadvantages enjoyed by the country practitioner in studying thetransmission of infectious disease.2 In his classic work on typhoid,carried out when at North Tawton, he wrote: "Having been bornand brought up in the village I was personally acquainted with everyinhabitant of it and being, as a medical practitioner, in almostexclusive possession of the field, nearly everyone who fell ill, cameimmediately under my care. For tracing the part of personalintercourse in the propagation of disease, better outlook could notpossibly be had."

MacKenzie and cardiologyPerhaps the most outstanding example of research in general

practice during the nineteenth century is provided by the career ofSir James MacKenzie.3 MacKenzie was born at Pickstonhill Farmin a village near Perth in Scotland in 1853. He did not excel atschool, and his mother was told by one of his teachers: "MrsMacKenzie, your James is the most stupid boy in the school." Thiswas the lad who was to graduate in medicine at the University ofEdinburgh in 1878, become a fellow ofthe Royal Society, and foundthe science of cardiology in Britain. In 1879, modestly having no

on 24 Septem

ber 2020 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://ww

w.bm

j.com/

Br M

ed J (Clin R

es Ed): first published as 10.1136/bm

j.295.6613.1614 on 19 Decem

ber 1987. Dow

nloaded from

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 295

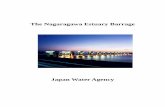

Dr William Budd, MD, FRs (1811-1880).

great confidence in his own abilities, MacKenzie went into generalpractice in Burnley in Lancashire, a sooty, smoke laden mill townwith rows of those interminable back to back houses that were somuch a feature of the industrial revolution in the north ofEngland.There MacKenzie invented the clinical polygraph, with which hewas able to record the pulsations ofthe jugular veins in patients withheart disease and in particular to demonstrate the nature ofwhat wenow call atrial fibrillation.Much of MacKenzie's work was done in his patients' homes

during the course of a busy day's round, and he wrote at night intothe small hours. His first cardiological papers were published in1891 and 1892. Within 15 years he had established a remarkableinternational reputation, corresponding with physiologistsat Cambridge and with Wenckebach in Groningen, and latercollaborating on the pathology of heart disease with Sir ArthurKeith. His fame also brought admirers as distinguished as SirWilliam Osler to visit him at his surgery in Bank House Street. Hedid not stay in Burnley, for in 1907 he moved to London, where heestablished a successful cardiological consultant practice and wherehis pupils included (Sir) Thomas Lewis.MacKenzie was associated in an unusual way with the country

practitioner who was to become the first president of the RoyalCollege of General Practitioners in Britain when it was founded in1952.4 While practising in Burnley. MacKenzie took care of thefamily of a wealthy mill owner, Mr Harry Tunstill, who in 1909built a large country retreat for himself and his family at a villagecalled Thornton Rust in the lovely valley of Wensleydale inYorkshire. He had one son and six daughters and the youngest butone was Gertie, who had been delivered by MacKenzie. In 1913Gertie met the new young doctor, Dr William Pickles, then 28 yearsold, who a year before had joined the practice in Aysgarth, two milesdown the valley. Like MacKenzie, Pickles had not always been themost successful of students. Although he finally graduated in 1909,he had failed both parts ofthe LondonMB when he sat for it in 1908and was ploughed in clinical surgery when he first attempted to gainthe licence of the Society ofApothecaries.'At Thornton Lodge the young doctor enjoyed the company of a

family that employed four housemaids, two pantry maids, a cook,four gardeners, a coachman, and several grooms. There were tennis

parties and dances in those halcyon days that preceded the firstworld war before the lights went out all over Europe. Pickles wentaway as a naval reservist during the war years, but in 1917 he wascanny enough to return to Aysgarth to secure the girl whose birthhad been supervised by James MacKenzie, andwhom he married inAysgarth Church on the 5 May.MacKenzie was to have an important influence on Pickles's

career. It was in 1926, at the age of 40, that Pickles first readMacKenzie's book ThePrinciples ofDiagnosisand Treatment inHeartAffections.6 MacKenzie had argued, cogently in that book that:"Whole fields essential to the progress of medicine will remainunexplored, until the general practitioner takes his place as aninvestigator." Stimulated by this book,' Pickles took refreshercourses inmedicinein London and Edinburgh in 1927 and 1929. Hewas also, apart from being a busy general practitioner, part timedeputy medical officer of health for his local district and.for thisreason had, always been interested, with his then partner Dr DeanDunbar, in 'the transmission. of infectious disease in his localcommunity. They had'both been impressed by-two successiveepidemics of jaundice in, the practice, 'and Pickles was particularlyconcerned to develop a system-to record these epidemics that wouldreplace tha haphazard methods of routine practice.

Epidemiology of hepatitisWith the advice of Dr Alison Glover of the Board of Education

and medical officer of the then Ministry of Health, Picklesdeveloped a deceptively simple but effective method of recordingthe infectious diseases that he encountered. Wensleydale then, asnow, contained several ancient villages or small towns, built in thegrey limestone of those Pennine valleys. Half a century ago, whencommunication was limited, electricity rarely existed, and familieswere mere self contained andisolated than today, the dales peoplewould meet with others from neighbouring villages only on specialoccasions-market days, funerals, weddings, or at annual shows,feasts, and the like. With the aid first of his daughter and. later ofGertie, his, wife, Pickles entered 'all the patients with infectiousdisease encountered' in his. daily rounds on charts that recorded onthe ordinate the villages in their natural social grouping and on theabscissa the dates on which each illness occurred. In this way, andby knowing from his patients who had met whom and when, hecould trace the progression ofany infection in the practice and alsodetermine its source. He studied influenza, measles, Sonnedysentery, varicella, herpes zoster, and any other infectious diseasethat came his way. 'But it was his studies ofinfectious hepatitis, thenknown as epidemic catarrhal jaundice, that were scientifically themost interesting. At that time there was considerable controversyover whether the condition was an infectious disease at all. Noincubation period had been clearly established, though workers

Dr William Pickles and his wife, Gertie.

19-26 DEcEmBER 1987 1615 on 24 S

eptember 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://w

ww

.bmj.com

/B

r Med J (C

lin Res E

d): first published as 10.1136/bmj.295.6613.1614 on 19 D

ecember 1987. D

ownloaded from

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 295

suspected that if there were an incubation period it might beprolonged. By the use of his charts and studies of individualepidemics within families and villages Pickles was able to show thatthe incubation period of the disease varied between 26 and 35 days.7His studies were an important contribution to establishing theinfectious nature of that condition.

Pickles described his work in a series of papers in the BMJ,Lancet, and elsewhere during the 1930s, and in 1939 he publishedhis classic work Epidemiology in Country Practice, a beautifullywritten book of little over 100 pages that should be commended toall who work in general practice or who seek to do SO.8 Thepreface tothe work was by Major Greenwood, first professor of epidemiologyat the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the mostdistinguished epidemiologist of his day and the predecessor of SirAustin Bradford Hill. In it Greenwood wrote: "Just as tropicalepidemiology received its greatest stimulus from Manson. the'doctor,' so will epidemiology of our own country receive a freshimpulse from discoveries made not by experts, but by medicalpractitioners working patiently on the lines of Dr Pickles." Pickles,in simple words that echoed those used by William Budd of his ownpractice, wrptethat he had stood on the summit of one of the noblehills of Wensleydile, the attractive little lake Semerwater appearing

to lie at his feet, and one by one he had made out most of the valley'sgrey villages, each with its thin cloud of smoke above it. "In all thosevillages," he recalled, "there-was hardly a soul, man, woman, or

child, of whom I did not know even the Christian name, and every

country doctor of long standing could say the same of his own

district."

Pickles died in 1969 at the age of 83. Like MacKenzie's, hispractice had become a place of pilgrimage and he was visited thereby two successive secretaries to the Medical Research Council, SirEdward Mellanby and Sir- Harold Himsworth. He had been Cutterlecturer at Harvard University, had been awarded an honorary DScat Leeds University, had an honorary FRCP of the Royal College ofPhysicians of Edinburgh, and was a proper FRCP of the Londoncollege. He had a CBE and had been awarded the James MacKenziemedal of the Royal- College of Physicians of Edinburgh and theBissett Hawkins medal of the London college. And when in 1952 agroup of general practitioners led by Dr John (now Lord) Hunt,encouraged by sympathetic specialist colleagues, sought to found acollege of general practitioners there was no question in the minds ofthe founders ofthe college as to who should be the first president. Itwas a remarkable achievement for a country practitioner from aYorkshire valley previously known predominantly for the quality ofits cheese.

In his declining years Pickles was blessed by partnership with ahusband and wife team who were outstanding doctors in their ownright and who supported him with great loyalty. At the end of thesecond world war Pickles was looking for a-new partner and took ona young Leeds graduate who had served as a medical officer in theRoyal Air Force. Dr Bernard Coltman came foran initial trial periodof three months. Itwas an appalling winter, the worst for 100 years,and some roads were blocked with snow for as long as eight weeks.Pickles was concerned that his new recruit would be discouraged.But the new doctor met everything in a sporting spirit and in June1947 broughtto Aysga4th a fellow Leeds graduate as his wife.9

It was Dr Katharine Coltman who, with her husband's edcourag-ment, was to be the most active of Pickles's partners in continuingthe traditions of research with which the practice had become sofirmly associated. In 1974 she was visiting an aunt in Hull when shetook the opportunity of attending the scientific meeting of theBMA, where she witnessed a demonstration of the McArthurmedical microscope.'0 Dr John McArthur is a remarkable man.Imbued with the philosophy that we are in this world for a purpose,he offered his services to the London Missionary Society as ayoung man. He encountered humiliation in Africa for befriendinghis African colleagues during the colonial era, and enduredimprisonment by the Japanese after being captured in Borneo anddespair when the World Health Organisation refused to take overhis work on eradicating malaria in the postwar period. But despiteall these vicissitudes he persisted with the idea that a microscope thesize of a miniature camera and powered by conventional batteriescould be used for work "in villages, in the field, or at the bedside."Dr Katharine Coltman was impressed by the Hull demonstration

and even more by Dr John McArthur's "Personal View," describinghis "long, often disheartening life," published in the BMJ inDecember 1975." The Coltmans purchased a McArthur micro-scope soon afterwards, at a cost of£260, with "a view to the earlydiagnosis of pyelitis of pregnancy and the possible prevention ofirreversible renal damage associated with pyelitis in children." Theinstrument was used at the bedside, in the back of the practiceLand-Rover, and in the surgery, and on one memorable occasion aurine sample was examined among the coffee cups of my ownbreakfast table, for my family home is within the confines of theAysgarth practice. It proved a pleasure to use and was particularlyvaluable in diagnosing and treating recurrent urinary infection. AsDr Coltman pointed out, it was a very good example of how a simpleexamination, requiring the minimum of equipment and technicalskill, could provide information of disproportionate value. Herwork on urinary infection in general practice was publishedin a series of articles in the Practitioner,'2 '4 and in 1982 she receivednational recognition when the British Medical Association awardedher its Charles Oliver Hawthorne prize, a prize given for "systematicobservation, research, and record in general medical practice."The use of the McArthur microscope in general practice has also

been described in detail by Dr Murray Longmore, whose Atlas ofBedside Microscopy describes his work during a general practicetrainee year in the south west of England." This beautifullyillustrated text shows how bedside microscopy can be applied to thestudy of blood films, white cell counts, and urinary deposits, and

1616 19-26 DECEMBER 1987

on 24 Septem

ber 2020 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://ww

w.bm

j.com/

Br M

ed J (Clin R

es Ed): first published as 10.1136/bm

j.295.6613.1614 on 19 Decem

ber 1987. Dow

nloaded from

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 295

that even phase contrast is within its capabilities. Undoubtedly it isequally valuable for diagnosing intestinal parasitic infection.

Virus infections of the respiratory tract

Pickles's influence, however, spread far beyond the confines ofhis own practice, and his work was an inspiration to anothercountry practitioner, Dr Ian Watson. Born in 1909, the son of adistinguished epidemiologist, he qualified at St Thomas's Hospitalin 1933 and proceeded MD in 1940. During the second worldwar he served in the Royal Army Medical Corps, working on theepidemiology of malaria. After the war he joined a general practiceat Peaslake in Surrey, in the valley of the Tillingbourne, which hechose deliberately as offering opportunities for research in generalpractice. He was particularly interested in virus infections of therespiratory tract. By then, however, laboratory facilities in Englandwere more highly developed than in the prewar period and Watsonwas able to establish a warm and fruitful relationship with DrGeorge Cook, director of the Public Health Laboratory at nearbyGuildford. In this way the epidemic disease that he encountered wasinvestigated not only with the classic clinical and epidemiologicalmethods used by Pickles but also with the modern techniques of thediagnostic laboratory. He was therefore able to describe the atypicalpneumonia caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in hispractice and when there were outbreaks of unusual febrile illness hewas able to show that they were due to Coxsackie A infection. One ofthose rare general practitioners who received grants for researchfrom the Medical Research Council, Watson was also a foundingfather of the Royal College of General Practitioners and a foundermember of its research committee. Also becoming honorarydirector ofthe college's epidemic observation unit, he twice, in 1954and in 1959, won the BMA's highest research award, the Sir CharlesHastings prize. Like Pickles, he was president ofhis college, servingfrom 1970 to 1972. His death in 1979 deprived general practice of aremarkable naturalist, epidemiologist, and research worker, but hiscollected writings, a work of considerable scholarship with aforeword by another distinguished practitioner, Dr J P Horder,were published posthumously by the college in 1982."

If so far I have dealt with the careers of individual generalpractitioners who have effectively contributed to medical know-ledge it is because until recently few official bodies were sufficientlyinterested in research in general practice. In recent decades,however, several important developments have encouragedresearch by groups of practitioners working together towards acommon end, rather than by the gifted amateur working on his own.The importance of the foundation of the Royal College of

General Practitioners cannot be underestimated.'7 Among itsresponsibilities under its royal charter the college is charged to:"encourage the publication by general medical practitioners ofresearch into medical or scientific subjects with a view to theimprovement ofgeneral medical practice in any field and undertakeor assist others in undertaking such research."' The college has aresearch committee, which specifically supports and encouragesresearch nationally. It has sponsored research fellowships, and fromthe earliest years much pioneer work was carried out.

Research at the RCGPThe institution of a number ofcollege research units"9 began with

the establishment of a research and statistical unit in Birmingham,now directed by Dr Donald Crombie, which is currently concernedin important studies of national morbidity. In Manchester thecollege unit has undertaken distinguished collaborative work withseveral general practices on the use of oral contraceptives and theircomplications, illustrating how a national organisation such as theroyal college can effectively bring together groups ofpractitioners toachieve statistically significant results that are of internationalimportance. Other work sponsored by the college has includedstudies of the respiratory sequels of pertussis infection in children,risk factors in coronary heart disease, the disturbing effects ofsterilisation in women, and the use of computers in recording

significant morbidity and family relationships in practice recordsaccumulated over more than 20 years.20 The amount of researchcarried out by members and fellows of the college is furtherattested by the more than 150 theses based on work in generalpractice now preserved in the college library."The college research units have, however, continually faced

problems of insufficient staffing and lack of security of tenure forresearch staff. There also appears to have been some ambiguity inrelationships between the units and the college itself. The unitsalso face increasing competition from the universities. The firstprofessor of general practice in Britain, Professor Richard Scott,was appointed by the University of Edinburgh in 1963,"2 and fewmedical schools now do not have a department of general practice.In fact, as Marshall Marinker has pointed out, "not to have such adepartment is no longer the hallmark of the traditionalist or thesuper technologist, but'merely of the quaint."23 Until now manyuniversity departments of general practice have concentrated onoperational or health services research, while the college researchunits have tended to focus on research into major problems ofpublichealth. In the future the university departments will no doubt moreeffectively complement the research role hitherto the prerogative ofthe college.

In all aspects ofresearch one ofthe most important influences hasbeen the scientific society or club. In Britain the Royal Society, theAssociations of Physicians and Surgeons, the Pathological Society,and a wide variety ofother specialist societies or research clubs haveall provided an important forum where friendships may be made,ideas exchanged, and collaborations established. In 1969 a GeneralPractitioner Research Club was founded in Britain after a 10 daycourse at the Royal College of General Practitioners on researchmethods in general practice. Subsequent meetings were usually aseries of whole day symposiums on a Saturday, preceded by aninformal dinner on the Friday with no speeches and no formalseating plan. The meeting often started with a presentation by a

19-26 DECEMBER 1987 1617

on 24 Septem

ber 2020 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://ww

w.bm

j.com/

Br M

ed J (Clin R

es Ed): first published as 10.1136/bm

j.295.6613.1614 on 19 Decem

ber 1987. Dow

nloaded from

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 295 19-26 DECEMBER 1987

statistician speaking on some aspect of research methods. Othertypical topics might include critical studies ofdevelopmental tests inthe delivery of medical care to children, middle ear disease, thebehaviour of different ethnic groups in respect of consultation, aswell as the experiences of a British general practitioner temporarilyworking in primary care in a country such as Sri Lanka. Britishgeneral practitioners are by no means chauvinistic. There is anactive European general practice research workshop, to which anincreasing number of practitioners from all over Europe belong andwhich in 1985 held'a successful one week training course atNorthwick Park, where the Medical Research Council's ClinicalResearch Centre and Epidemiology and Medical Care Unit aresituated.

Role of the MRCSo far I have said little of the role of the Medical Research Council

in Britain. The MRC, originally the Medical Research Committee,founded in 1913, came into being in its present form in 1920. In1914 Sir James MacKenzie (in the later years of his consultingpractice in London) had suggested forcibly to the Medical ResearchCommittee that disease in general practice presented itself in atotally different manner from that in hospital practice; there was anurgent need to encourage research into the early stages of diseaseand into the course and natural history of chronic disease. Althoughthere was some sympathy for MacKenzie's views, there was'generalagreement then that little would be achieved by supporting researchby general practitioners and no advances in knowledge werelikely to come from the amassing of clinical facts by untrainedobservers,25 a view belied by subsequenttevents in Wensleydale.MacKenzie retired from London practice in 1919 and set up at StAndrews in Scotland an institute of clinical research, which was toconcentrate on the early symptoms of disease and its natural course,

but which would also be concerned in training general practitioners.MacKenzie approached the then secretary of the MRC, Sir WalterFletcher, somewhat reluctantly and with a degree of belligerencethat Fletcher took in good part, for he gave a measure of support tothe venture until MacKenzie's death in 1925. Without MacKenzie,however, the institute gradually declined and the council, whichhad been invited to take it over. decided that the project was nolonger viable.25William Pickles shared MacKenzie's views on the Onportance of

the general practitioner in medical research, arguing in respect ofhis own studies of e-pidemic myalgia, for example, that "noconsulting physician can have the opportunity to follow the wholecourse of such a disease in the same way as a general practitioner."Pickles was aware that by the late 1920s the MRC was investigatingepidemics in boarding schools in England, and, writing in 1939, hesuggested that similar work could well be undertaken by "a numberof doctors practising in remote districts in different parts of thecountry," going on to suggest that such a service should beorganised by the MRC.26 In the years since then there have beendesultory attempts by the council to encourage research in generalpractice. In 1947 an epidemiological research unit was set up atCirencester in Gloucestershire under the direction ofDr R E HopeSimpson, who was in practice there. Among other achievementsHope Simpson confirmed that herpes zoster and varicella were dueto the same virus,2" an association that had been first made inBelgium in the 1880s and further investigated by Pickles during hisown epidemiological studies.

Mild hypertension trialIn the modern era, however, the MRC has established just such

an organisation as Pickles originally suggested. Stimulated byProfessor (now Sir) Stanley Peart, in the early 1970s the councildecided to investigate the value of treating mild hypertension ingeneral practice. A successful pilot study was first carried out,28 andin 1977 a working party was set up to guide an investigation intowhether drug treatment of mild hypertension would be associatedwith a reduction in the number of deaths due to stroke or tocoronary artery disease. At the same time the opportunity was takento compare the effects of two different therapeutic regimens and toassess the incidence of adverse reactions and side effects. It was amammoth undertaking coordinated at Northwick Park by DrW EMiall working in the council's Epidemiology and Medical Care Unitdirected by Dr Tom Meade, and with the help of Dr GillianGreenberg. The interest of potential participants was attracted byletters in theJow'nal ofthe Royal College ofGeneralPractitioners, theLancet, and theBMJ and to a small extent by direct approach fromcolleagues. The requirements were that there must be at least oneinterested partner in the participating practice, a list size of 8000 ormore, and adequate space for research to be carried out and papersand drugs safely stored. Participating doctors were reimbursed atclinical assistant rates and nurses, who carried out the greatestproportion of the actual work of measuring blood pressure andrecording progress, at standard scales ofpay.About 175 group general practices all over England, Scotland,

and Wales took part in this study, and the results have now beenpublished.29 Some 17 354 patients were recruited and 85 572 patientyears of observation accrued. An enormous amount of valuabledata emerged. Evidence was provided that active treatment wasassociated with a reduction in the rate of stroke overall, but therewas no clear effect on the incidence of coronary events. In terms ofactual numbers, however, it was perhaps disappointing to critics ofthe study, some ofwhom appear to be less than sympathetic to theuse of the MRC's resources for controlled clinical trials, that forevery 850 mildly hypertensive patients treated for one year onlyabout one stroke would be prevented. Nevertheless, as always withwell conducted trials, the facts were established and are there tostay.There is, however, far more to the establishment of the MRC's

general practice research framework than the treatment of mildhypertension. It now includes about 300 general practices nation-

1618

I:I----

%.I.-

Amvlv,.K

on 24 Septem

ber 2020 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://ww

w.bm

j.com/

Br M

ed J (Clin R

es Ed): first published as 10.1136/bm

j.295.6613.1614 on 19 Decem

ber 1987. Dow

nloaded from

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 295 19-26 DECEMBER 1987 1619

wide. A remarkable and unique instrument has been set up withwhich a wide range of other problems may now be investigated ingeneral practice, something that would have been dear to the heartsof both MacKenzie and Pickles. Among other topics the feasibilitystage ofa study oflow dose anticoagulant therapy in the preventionofacute coronary occlusion has now been reached and studies are inprogress to investigate the role of the general practitioner in theprevention of problem drinking. An investigation of the use ofhormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms has justbeen completed, and an interesting proposal is at the design stagefor a study of the most effective way in which general practitionerscan help their patients to stop smoking. The Epidemiology andMedical Care Unit aims at continuing to foster such studies (TWMeade, personal communication).

For the future I believe, with Professor J G R Howie,n0 Dr JohnFry, and many of their colleagues, that there is still a role for theindividual general practitioner in the prosecution of research,particularly in the study of infectious disease, the organisation andrunning of primary care services, the use of drugs, or socialproblems such as behavioural disorders and bereavement, as well asthe management of pain and the care of the chronically ill. I alsobelieve that collaborative studies between many general practi-tioners, as in the investigation of the problems of the contraceptivepill by the college research unit or in the MRC's hypertension trial,have already shown their value. Furthermore, it is important not toaccept that you are incompetent because a schoolmaster of limitedbrain thinks you are an idiot, or to be discouraged if some elderlyexaminer fails to recognise your virtues in a final examination. It hassurely also been established that the surgery of a general practicemay have just as much right to be known as a "centre ofexcellence"as any of those metropolitan institutions of higher learning that layexclusive claim to that title.

I thank many friends and colleagues who have given advice during thepreparation of this paper, particularly Dr Stuart Came, Dr Tony Keable-Elliott, and Dr Marshall Marinker; I am also indebted to Dr GillianGreenberg, Professor Andrew Haines, and Dr T W Meade of the MRC'sEpidemiology and Medical Care Unit at Northwick Park. I am speciallygrateful to Dr Bernard and Dr Katharine Coltman, lately of the Aysgarthpractice, for much helpful discussion, and to Professor CourteneyBartholomew, of the University of the West Indies in Trinidad, forencouraging me to approach the subject of this essay.The drawings of Wensleydale in this article and the painting on the front

cover are by Ghislaine Howard.

References1 Budd, W. Typhoidfever. London: Longmans Green, 1873.2 Goodall EW. WiUiamBudd. Bristol: JW Arrowsmith, 1936.3 MairA.SirJamesMacKenzieMD 1853-1925. Generalpractisioner. London: ChurchillLivingstone,

1973.4 College ofGeneral Practitioners. First annual meeting and first president. Lancet 1853;ii: 1087.S Pemberton J. Will Pickles ofWenseydae. London: Geoffrey Bles, 1970.6 MacKenzie J. The princips ofdinosis and tranem in heart affections. London: Henry Frowde,

Hodderand Stoughton, 1916.7 Pickles W. Epidemic catarrhal jaundice: an outbreak in Yorkshire. BrMedJ 1930;i:944-6.8 Pickles W. Epidemioiy in conty practice. Bristol: John Wright, 1939.9 Booth CC. A retirement party in Wensleydale.JR Col GenPract 1985;35:546-7.10 McArthur J. Advances in the design of the inverted prismatic microscope. Journal of the Royal

MicroscopicalSociey 1945;65:8-16.11 McArthurJ. Personal view. BrMedJ 1975iv:702.12 Coltman K. A-new technique for detecting urinary tract infection. Practioner 1975;221:243-6.13 Coltman K. Urinarytractinfections. Newthoughtsonanoldsubject. Practioner 1979;223:351-5.14 Coltman K. Urinary screening in general practice. Pracetioner 1981;225:668-72.15 Longmore JM. An adas of bedside ncroscopy. London: Royal College of General Practitioners,

1986.16 Watson GI. Epidemiology and research in general practice. London: Royl College of General

Practitioners, 1982.17 Fry J, Hunt JHH, Pinsent RJFH, eds. A history of the Royal Colege of General Practtioners.

Lancaster: MTP Press, 1983.18 Mayo J. Incorporation, royal prefix and the royal charter. In: Fry J, Hunt JHH, Pinsent RJFH,

eds. A history oftheRoyal ColUge ofGeneral Practitioners. Lancaster: MTP Press, 1983:205.19 Pinsent RJFH, Watson GI. The college and research. In: Fry J, Hunt JHH, Pinsent RJFH, eds. A

histoay of the Royal ColUge ofGeneral Pracitioners. Lancaster: MTP Press, 1983:13144.20 College Research Units. Report of meeting of unit directors, June 1984. J R Coil Gen Pract

1984;34:501-2.21 Anonymous. Theses on general practice held inRCGP library. London: Royal College ofGeneral

Practitioners.22 Anonymous. Edinburgh general practice chair. BrMedJ 1963;ii:1212.23 Marinker M. Should general practice be represented in a university medical school? Br Med J

1983;286:855-9.24 Anonymous. The general practitioner research club._JR CoUGen Pract 1981;31:70-1.25 Thomson AL. Halfa cenoy ofmedical research. 2. Theprogramme oftheMedical Research Concil.

London: HMSO, 1975:20.26 Pickles W. Ep ide in counypractice. Bristol: John Wright, 1939:7.27. Thomson AL. Halfa centoy ofmedical research. 2. Theprogramme oftheMedical Research Comcil.

London: HMSO, 1975:21.28 MRC Working Party on Mild to Moderate Hypertension. Randomised controlled trial of

treatment for mild hypertension: design and pilot trial. BrMedJ 1977;ii: 1437-40.29 MRC Working Party. MRC tral of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Br MedJ7

1985;291:97-104.30 Howie JGR. Research in general practice. London: Croom Heim, 1979.

Clinical Research Centre, Harrow HAI 3UJCHRISTOPHER C BOOTH, MD, FRCp, director

Address given at 10th Update on Important Topics in Medicine, organised byDepartment of Medicine, University of West Indies, Port of Spain, Trinidad,10 January 1987.

No Christmas in China

In the People's Free Republic of China we do not have Christmas.We have Chinese New Year, the Moon Festival, Dr Sun Yat Sen'sbirthday, and Independence.Day, but no Christmas. We do nothave weekends either: they are a Christian invention. We cannoteasily buy radios that receive stations outside Taiwan, and our postis opened (both for political purposes). We cannot take photographsof the stunning sea views (for defence reasons), but what we can dois buy drugs-lots of them, all sorts, all colours, all shapes, and allsizes, with or without package leaflets-and have injections,compresses, or infusions from a doctor, a chemist, or even a friend.It used to be that the local chemist could put tip an infusion foryou-again with a wide choice of stock, cost, pharmacologicaleffect, volume, and venous access site, and all available with orwithout medical or paramedical advice.That is, I guess, ifyou have the money. Ifyou have not the various

government health insurances cover you, or nearly cover you,unless you are one of a minority group-of selfemployed Bunin orAmi tribal peoples, for examplwho cannot afford the cost ofinsurance even after working seven days aweek on the land. Howdothey manage? Very poorly indeed when the cost of one day's paimreliefequals a day's earnings. Alternative sources ofmedical care arethe mission hospitals, which provide acomplementary service to thepeople alongside (or probably after) the traditional bone setters,acupuncturists, herbalists, chiropractors, moxibustionists, andlocal Taiwanese doctors.

Being brought up on a good British diet ofthe Prescriber'sJ7ournaland the British National Formulary, and with a hand on my heartbelief in the goodness of the Drugs and Therapeutics Buletin, it wasall a bit much-the pink tablets, the green ones, the little orangeones (unlabelled, unmarked, with no expiry date), all prescribed inthe past few days by different doctors for the same symptoms.Where are the old stalwarts? Butazolidine, for example, or thecontact amoebicide clioquinol: reliably made, quality controlled,and with package leaflets., and marketed only after painfullyexpensive animal studies, studies on human volunteers, andcontrolled clinical trials. Effective and inexpensive, made byreputable transnational companies, but nevertheless withdrawnbecause Western standards of risk assessment and Western views ofthe quality of life have been assumed with some arrogance, to beglobally applicable. The resultant cultural imperialism is appliedand felt here by restrictions imposed there.Why is it that one or two articulate pharmaceutical experts can

hold sway, determining the comfort or disease of so many people?And how can they so glibly assume that they are uniformly right andmobilise media support for their own particular twentieth centuryphannaceutical crusades? Everyone knows that amidopyrine cancause bone marrow aplasia, but the risks ofsnake bite, the effects ofcrop failure, and the perennial problem of poverty are far morerelevant here.

Isn't it time someone told the drug consumerists that we do nothave a Christmas in China?-T TAULXE-JOHNSON, Holy CrossHospital, 95601 Kuanshan, Taitung Hsien, Taiwan.

on 24 Septem

ber 2020 by guest. Protected by copyright.

http://ww

w.bm

j.com/

Br M

ed J (Clin R

es Ed): first published as 10.1136/bm

j.295.6613.1614 on 19 Decem

ber 1987. Dow

nloaded from

![[PPT]PowerPoint Presentation - · Web viewThe Feudal and Manorial Systems Preview Main Idea / Reading Focus The Feudal System Quick Facts: Feudal Obligations The Manorial System Daily](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5ab479377f8b9adc638c1c98/pptpowerpoint-presentation-viewthe-feudal-and-manorial-systems-preview-main.jpg)