Islamic Geometric Ornament: The 12 Point Islamic Star. 5: Blue Mosque of Aqsunqur

Contemplating Islamic Geometric Design

-

Upload

suhayl-salaam -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Contemplating Islamic Geometric Design

-

7/29/2019 Contemplating Islamic Geometric Design

1/4

Contemplating Islamic Geometric Design

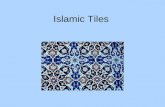

Geometrical designs are among the most recognizable expressions of Islamic art and culture among Muslims and non-Muslims alike

by ERIC BROUG

Throughout the history of Islamic architecture, craftsmen have adorned buildings with geometrical designs. Thesedesigns are still among the most recognizable expressions of Islamic art and culture among Muslims and non-Muslimsalike. But as with all art that causes us to gaze in awe, it is easy to forget that at some time in the past, Islamic craftsmensat down and designed and executed these designs. Here we look at two geometrical designs, one from Cairo and onefrom the Alhambra, and uncover their secrets

Behind the al-Azhar mosque in Cairo is a group of buildings built in the late 15th century by the famous Mamluk sultan, al-Asraf Qaytbay. It consists of a wikala (a medieval market or mall) and a sabil-kuttab. The latter building is a traditionalMamluk multi-purpose structure where, on the ground floor, behind a metal lattice screen is a drinking fountain (sabil). Onthe floor above, with double arches on both sides is a primary school (kuttab). The street-facing walls of these buildingsare richly decorated with geometrical designs. There are stone panels with designs framing doorways, the voussoirsabove the windows and storefronts all have individual designs, and even the capstone in the star vault entrance to thewikala has a geometrical design. Between the sabil on the ground floor and the kuttab on the first floor is a geometricalpanel that wraps around a corner, as can be seen in the photo. Some of the patterns are repeated but mostly the designsare all different from each other. What they have in common are two features that are characteristic of geometricaldesigns made during the reign of the Mamluk sultans (1250-1517 AD). First of all, the designs show only part of a largercomposition; they invariably show only a half or a quarter of a traditional star design. Secondly, most of the designs havekite-shapes that serve as links in a chain, connecting the individual star designs.

The wikala and sabil-kuttab are from the very end of the reign of the Mamluks and built during a period that is commonlyconsidered to be the apogee of Mamluk art and architecture: the reign of sultan Qaytbay. This sultan commissioned theconstruction of many beautiful buildings in Cairo and his patronage encouraged lesser sultans and emirs to do likewise,both during and after his reign. His mausoleum is one of the most refined buildings in Cairo; it is situated in the NorthernCemetery and is best known for its exquisitely decorated dome, which interweaves geometrical patterns with plant motifs.

On the exterior of the sabil-kuttab is a number of stone panels that show details from larger geometrical star designs. Thearea directly around this relatively simple doorway has been elaborately decorated. All these have been furtheraccentuated by the double interlacing stone banding. Above the stone banding and outside the frame of the picture is ahuge floriated rosette of at least 150cm diameter. The stone ornamentation is there to draw attention to the doorway.

Above the doorway, on either side of the window, are two square panels: they are each other's mirror image. These twopanels are typical of Mamluk design because they show a detail of a larger composition. They do not show us traditionalstar designs: they only show us the areas between the star designs. This exact same panel also appears on the qiblawall [direction worshippers orient themselves] in the mosque of Qiqmas al-Ishaq (built during the reign of SultanQaytbay), where it is painted in blue, gold and white. Similarly, the design on the lintel above the door appears on amuch larger scale on the dome of the mausoleum of sultan Qansuh Abu Said in the northern cemetery of Cairo. Boththese examples indicate that certain designs were popular, or that the craftsman who was able to make these designs

was popular. Perhaps the lesser emirs of sultans in Cairo wanted to bask in the reflected glory of Sultan Qaytbay byusing the same designs that were on his buildings.

Islamica Magazine

http://www.islamicamagazine.com Powered by Joomla! Generated: 11 August, 2008, 00:58

-

7/29/2019 Contemplating Islamic Geometric Design

2/4

The panel contains three design elements including a star design and a "kite" shape that acts as links in a chain. Theyhold the elements in the composition together. Other lines in the panel reveal their shape and function less readily. Inorder to make a full star, the quarter sections have to be arranged in such a way that they all join. To do this, the panelhas to be mirrored, which allows the floral decorations to become visible. Five-petalled flowers and traditional vine & leafmotifs fill up the spaces between the interlacing bands of the design. The use of floral and vegetal motifs is at the heart oftraditional Islamic design. They provide a counterweight to the straight lines of a geometrical pattern.

There are many panels such as this one in Mamluk Cairo, although they vary in size, location and material. The mainquestion that springs to mind is "why?" What was the reason that Mamluk craftsmen made panels that showed a detail ofa larger design? It is a design style truly unique to the Mamluks. The panels demonstrate the skill and creativity of thecraftsmen in Cairo at the time; they were truly masters of their trade. They were so well versed in geometrical design thatthey were able to innovate the way it was presented and develop new ways of showing a traditional and familiar artisticexpression.

The Mamluk craftsmen evidently wanted to create geometric designs that engaged the citizens of Cairo. By purposelyshowing a small part of a big composition, they challenge the passer-by in streets of Cairo to complete the design in hismind. It is as if the craftsman is saying: "Here is a small detail. Let's see if you can visualize what the complete picture

looks like." They challenged the citizens of Cairo to use their intellect, their memory and their creativity. They encouragedthem to contemplate the geometric design and possibly, by doing so, allow them some time to reflect on something otherthan their daily, hectic environment. Medieval Cairo would have had the same bustle of activity as it has today. Walkingthrough the city, you would pass dozens of buildings, some grand, some mundane. Many of these buildings are adornedwith a great variety of geometrical designs. Medieval city dwellers would have been able to recognize the occurrence ofthe same designs on different buildings. The ubiquity of geometrical designs in the cities of the Islamic world shows thatthe people living in these cities had an affinity with geometrical design that is hard to appreciate for us living in the 21stcentury. The pervasiveness of geometrical design in medieval Islamic societies created in the mind of city dweller aprofound familiarity with the wealth of different designs.

{sub type="reg"}

What, then, was the design that the craftsmen who made the twin stonepanels wanted the citizens of Cairo to visualize? By mirroring onepanel, we get four quarters of the star design in the center allowingthe design to reveal itself.Now that the complete design is visible at some level, we know what aMamluk craftsman from late 15th-century Cairo wanted us to see with ourmind's eye. The design that has been created by mirroring one stonepanel can itself again be mirrored, and that new design can then be

mirrored again. This process can be repeated infinitely, and it is theessential attribute of Islamic geometric design.

Fortunately, not all geometrical designs are as complex as those of theMamluks. In most cases, craftsmen used geometrical designs for theornamentation of a surface. Such designs commonly consist of one, twoor three design elements that are combined and repeated many times.Usually these elements can be contained in shapes that can be repeatedinfinitely by being placed next to each other. Usually these elementsare a square, a triangle or a hexagon. In the case of the Mamluk panel,the square was the element that allowed infinite repetition.

Islamica Magazine

http://www.islamicamagazine.com Powered by Joomla! Generated: 11 August, 2008, 00:58

-

7/29/2019 Contemplating Islamic Geometric Design

3/4

This design from the Alhambra in Spain is made in incised plaster andcovers an interior surface. It is constructed by the repetition of stardesigns to cover a large surface area. Here, there are no kite-shapedlinks holding everything together the design consists ofuninterrupted bands that travel from the top to the bottom and from the

left to the right of the wall.

When confronted with such an elaborate composition, one of the firstquestions that springs to mind is, "how did they do that?" "How didthey achieve such perfection and regularity?" It is tempting for us inthe 21st century to see Islamic geometrical designs and use our owntools of analysis to better understand these designs. But it isimportant to realize that traditional craftsmen were usually notnumerate. They would not calculate angles in order to make theircompositions: their knowledge of geometry was practical, nottheoretical. Their tools of the trade were a compass and a ruler. With

these tools they drew circles and lines and, by connectingintersections of these circles and lines, they created patterns. Whenwe look at Islamic designs, beauty and complexity seem to go hand inhand. But are these designs complex because we do not have the sameaffinity with geometry as people in traditional Islamic societies usedto have? Would what we consider to be complex also have been consideredcomplex by medieval citizens of Cairo or Konya or Granada? Complexity,like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. It is possible that theywere able to see and distinguish aspects of geometrical patterns thatwe are no longer able to. This is certainly true of the geometricalpanel from Cairo that we have looked at; it does not reveal its secretsreadily. This is compounded by the fact that we are not accustomed toseeing geometrical designs on a daily basis. and do not have that

familiarity that people would have had in traditional Islamicsocieties.

The perfection, regularity and harmonious proportion that is evident inthe Alhambra composition was achieved by first constructing a simplefoundation composition out of hexagons. This composition would notremain visible once the geometrical design was finished. The foundationcomposition or "grid" allows the craftsmen to place the composition ona surface and ensures that the size of the individual components is inan appealing proportion to the overall surface area. Just as medievalIslamic craftsmen used the grid system to construct a composition, this

same design technique can be used to deconstruct a composition.

By looking at the design and discovering where the design elementsrepeat, it becomes possible to see the hexagonal grid that was used-thered lines show its location. The craftsman would have used this gridbefore making the final design. It shows that each hexagon contains thesame design. The design that is used for this composition is atwelve-pointed star. The overall composition can be furtherdeconstructed by looking at how the twelve-pointed star design in thehexagon is made.

Like all Islamic craftsmen, those in the Alhambra would have used acompass and a ruler to construct the grid and the design. Allgeometrical designs begin with a horizontal line on which a circle is

Islamica Magazine

http://www.islamicamagazine.com Powered by Joomla! Generated: 11 August, 2008, 00:58

-

7/29/2019 Contemplating Islamic Geometric Design

4/4

placed. The craftsman will then decide whether to divide the circleinto, for example, 5, 6 or 8 equal parts. This decision will determinehow the design will develop and whether the design will fit into apentagon, a hexagon or a square. The composition from the Alhambra canbe reconstructed by taking the same design steps that the craftsmanwould have taken. In all geometrical compositions there are differentlayers in which the viewer is invited to focus. Some are immediatelyvisible; others reveal themselves after closer observation. They all

share their invitation to contemplate the design and what it representsand symbolises to each individual. They invite the viewer tocontemplate issues such as the seen and the unseen, beauty and order,the infinitely small and the infinitely big, foundation and structure,and of course, the notion of creation itself. Different eras andregions in the history of the Islamic world have used geometry in theirown specific ways to express these concepts and issues.

The small panel from Cairo and the composition from the Alhambra bothinvite us to contemplate the large and the small, the part and thewhole. The panel from Cairo might be understood to convey this notion:

"you will understand the complete design through understanding thesignificance of the small part and its role in the complete design."The Alhambra composition might be understood to convey, "Do not standtoo far back lest you only see the complete design. Do not stand tooclose lest you only see the detail."

There is more that we don't know about Islamic geometrical design thanwhat we do know. Hardly any historical documentation exists of howcraftsmen worked or how they interacted with their patrons. We don'tknow what their status was in society or how knowledge was transferredamong craftsmen and from generation to generation. Nor do we know

whether the craftsmen who made geometrical designs on walls were alsoable of making designs for a curved surface, like a dome. The challengethat the lack of historical written information poses to Islamic artand architecture in general is the need to learn by looking at thebuildings and objects themselves. They have a great deal of informationto give us if we look closely and look with an open mind.

ERIC BROUG has studied Islamic geometry for over fifteen years. He was educated at VITA and SOAS and his recentbook on Islamic geometry was published by Bulaag Publishers in Dutch. For more information, please visitwww.broug.com

{/sub}

Islamica Magazine

http://www.islamicamagazine.com Powered by Joomla! Generated: 11 August, 2008, 00:58