Construction IndustryContract (CIC-1)1997

Transcript of Construction IndustryContract (CIC-1)1997

ACLN - Issue # 57 6

-r------------------ Contracts -----------------111

Construction Industry Contract (CIC-1) 1997

John L Pilley, Executive Director,Construction Industry Engineering ServicesGroup Ltd &Managing Director, Gorham PtyLtd.

These Conditions of Contract were launched on 14October 1997 with a fanfare from the Royal AustralianInstitute of Architects ("RAIA"). They received a frostyblast from the MBA especially in the Australian FinancialReview. CIESG endorses the MBA stance that the CIC-lmerely adds yet another form of contract to the plethoraof documents prevalent in the industry at a time whencontractors and subcontractors are suffering enough stressdue to extremely tight margins and low prices. Anotherform can only add to tendering costs because CIC-l is yetjust another form which has to be evaluated for risk aspart of the tendering process when that document is used.

A yellow Explanatory Memorandum for CIC-l hasbeen issued by the RAIA and has an ExplanatoryMemorandum which extols the virtues of CIC-l.

A number of points on this explanatorymemorandum should be noted:

1. It is said the CIC-l ...

"sits between SBW-2 and ICC. As such, itsoptimum use should be for constructionprojects with a value of$100,000 or more".

This does not state any upper limit, sopresumably there is not intended to be anupper limit. With respect, CIC-l appears tobe a replacement for ICC especially as itattempts to incorporate strict time bars onclaims by the contractor which are absentfrom ICC. Therefore, CIC-l could be seento be a document which the RAIA hopesowners will use rather than ICC, since thedocument attempts to give the owner moreprotection from claims by the contractor.

Many owners regard ICC as too pro-builderwhich is probably why most major projectsowners who use ICC substantially amend itto limit claims and to transfer risks usuallyborne by the owner under ICC to the builderinstead.

2. The Explanatory Memorandum also explainsthe change from the use of the titlesProprietor and Builder (as in ICC) to ownerand contractor in CIC-l. It asserts:"Standards Australia ... have, for some time,utilised the words owner and contractor".This is incorrect. Contractual Standards suchas AS2124 always use the word Principal andnever use the word owner.

3. The Explanatory Memorandum explains thatdefinitions in CIC-l are contained in" theclause where they are first used. This iscontrary to modern drafting practice, e.g.C21, AS4000, where definitions are usuallyin a separate clause for easier reference. Toplace a definition in the clause in which it isfirst used means that a user may not realisethe term is defined elsewhere when it isreferred to later in CIC-l. CIC-l mightconfuse users into thinking all definitions areon pages 47-48 by use of a footnote to thateffect on each page - in fact only 4 definitionsare contained on pages 47 and 48. In additionthis footnote is on each page preceded by anasterisk. If one of the 4 definitions on pages47-48 is not referred to on the particular page,one searches in vain for the reference to theword as defined on that page. In fact, one ofthose 4 definitions occurs only on pages 4,21, 27, 38, 42, 43 and 46; yet the asteriskedfootnote occurs on every page from page 3to page 62 including all the schedules.

Important terms such as "site", "variation","contract sum", "instruction" are either notdefined or have a meaning difficult toascertain from the use of the word in theclauses. Some other terms which are used "practical completion", "separable part","latent condition"- also fall into this lattercategory.

ACLN - Issue # 57

Furthermore, CIC-l does not identify adefined term when used in the document bythe use of bold print, italics, etc., whichmakes it difficult to ascertain whether a wordor expression not being one defined on page47 or 48, is defined elsewhere in thedocument. The document is consequentlyfar from user friendly, despite the fact itappears to be set out in modem format whichis attractive to the eye. The emphasis seemsto be on making the document superficiallypleasant to look at rather than easy to use.

4. The Explanatory Memorandum also assertsCIC-l adheres to the "Abrahamsonprinciple" that "risks lie with the party mostable to control them". This assertion isprimarily to support and justify the liabilityand insurance provisions especially as itstates that insurance is to be effected by thecontractor under CIC-l rather than providingan option for insurance similar to JCC wherethe first option is that the Proprietor insures.It is the writer's view that it is unfortunatethat CIC-l uses the liability clause as anexample of the fairness of the document inrespect to risk allocation. The liability clauses(Section D), in the writer's view, are a disasterand attempt to allocate risk very unfairlyespecially against the contractor. However,as will be demonstrated later in this reviewof CIC-l, the liability clauses (Section D)also adversely prejudice the owner andrequires the owner also to bear risks it cannotcontrol.

This paper will demonstrate in severalimportant areas that CIC-l does not complywith this Abrahamson principle, in additionto the area of liability.

5. Finally, it is asserted in the ExplanatoryMemorandum that CIC-l ...

"sets a new and important benchmark forconstruction contracts in Australia withrespect to fairness and equity and allocationofrisk".

This paper will demonstrate that CIC-l is neitherfair nor equitable. Its language is far from clear in manycases. Rather than reducing disputes, it is the writer'sview it leaves open many areas for dispute, which isexacerbated by draconian time limits imposed only on thecontractor if it wishes to claim time or money, a fact likelyto induce extra-contractual claims despite the efforts ofthe RAIA to exclude these by Clause M5.

In addition to the Explanatory Memorandum, alsosupplied is a check list of actions by the parties to the

7

contract. This sets out in order of the clauses in the contractthe main actions to be taken by a party and when thoseactions are to be taken.

Whilst this is a useful document it over-simplifies(as it must) and, therefore, potentially misleads the useron what action is to be taken and when it is to be taken. Inaddition, it deals with time in "days" whereas the contractuses "working days". Whilst this is probably notprejudicial to a party required to give a notice under thecontract, nevertheless it would have been useful at thecommencement of this explanatory document to warn theusers of this caution list that "days" when mentioned inthe document means working days and not calendardays.

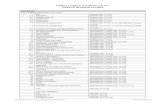

FORMATThe Contract is divided into 13 Sections followed

by 5 Schedules. The Sections are:

A Overview3 clauses setting out the fundamental obligations ofthe parties and the architect;

B Documents4 clauses dealing with contract documents;

C Security9 clauses dealing with security;

D Liability4 clauses dealing with liability for risk;

E Insurance13 insurance clauses;

F the Site17 clauses;

G Building the Works23 clauses dealing with building the works includingprogramming, suspension, testing, separatecontractors;

H Variations to the Works10 clauses;

J Completion of the Works25 clauses including practical completion,extensions of time, defects and defects liability;

K Payment16 clauses including progress claims and certificatesand final claim and certificate;

L Termination23 clauses including termination for owner's ownconvenience;

M Miscellaneous this section deals with governinglaw, dispute resolution and other various matters;

N Definitions4 definitions are set out in one clause.

The 5 Schedules are:1. Contract Information;2. Special Conditions;3 Specifications, Drawings, etc.;4. Site Information;5 Bank Guarantee.

ACLN - Issue # 57

It is submitted that these Schedules are inadequatein that they provide no guidance to the parties drawing upthe contract how the information to be inserted in theSchedules is to be set out or indeed, what information isneeded. This article will demonstrate that the provisionsof Clause B2 combined with the lack of guidance inSchedule 3 which is relevant to Clause B2 are a disasterand could lead to endless disputes, unless the parties areextremely careful when listing the contract documents inSchedule 3.

There is also no Index to the document, whichexacerbates the problem of finding words which aredefined.

DETAILED COMMENTThere is provision for the parties to execute the

document on pages 1 and 2. The document curiouslyassumes that the contractor will always be a company,whereas options are provided for the owner to be anindividual or a corporation.

There is also a Warning at the bottom of page 2 thatthe contract sum "may be subject to variations due to thefollowing provisions". Whilst it is useful to have this listitemised, in fact some of the clauses do not raise a"variation" in the sense used by the document in SectionH - Variation to the Works. For instance, clauses G7,G12 and G16 which are referred to, do not specificallyraise a variation under those clauses. It would have beenmore useful and accurate if the Warning notice had stated"may be subject to adjustment due to the followingprovisions". The word "due" is also ambiguous;"pursuant" would have been more appropriate.

Section A - OverviewUnder clause Al the contractor must begin the

Works within 10 working days after receiving the"required authority approvals". This expression is notdefined and it is not apparent from the clause who is toobtain these approvals.

Approvals will probably be a matter for theSpecification. Section JI0 lists 19 causes of delay whichentitle the contractor to make a claim for adjustment oftime. Cause 10 deals with approvals by authorities. Cause10 permits the contractor to apply for an extension of timeif there is a delay by an authority, including a privatebuilding surveyor, failing to give prompt approval for theworks except when that is caused by an act or omission ofthe contractor. Furthermore, the contractor can initiatethe cause for an extension of time if the contract providesthat the owner is to obtain these approvals by firstly,applying for an extension of time under clause 16. It maybe also a breach of the contract by the owner if the ownerhas failed to obtain the approvals, which entitles thecontractor also to claim adjustment of time costs underClause J18.

The problem the contractor faces in relation todelays when the approval is to be obtained by the owneris because of the draconian time limits imposed on thecontractor for applying for an extension of time under

8

Section J11. This applies right throughout this documentwhenever the contractor wishes to apply for an extensionof time or indeed make a claim of any sort. Section Jllmakes it a condition precedent to the making of a claimfor an adjustment of time that the contractor complies withthe 5 dot points set out in that clause. The first of theseconditions precedent is that within 2 working days afterthe contractor becomes aware of the circumstances givingrise to the claim, it must notify the architect in writing ofits intention to make the claim. This abnormally shorttime for making an extension of time claim (it is theshortest time in any contract of which the author is aware),seems designed primarily to limit the principal's exposureto the consequences of extensions of time, especially fordelays which are not caused by the principal when the actofprevention rule might otherwise force the architect intogranting an extension of time even though the contractorhas failed to comply with these conditions precedent bygiving the necessary notices.

I say "notices" rather than notice because not onlymust the contractor within 2 working days give notice inwriting of its intention to make the extension of time claim,but it must within a further 3 working days after thecontractor becomes aware of the circumstances giving riseto the claim, i.e. within 3 further working days, specify inwriting to the architect the details and the adjustment thatthe contractor is seeking to the date for practicalcompletion. Again, this draconian time limit seemsdesigned to attempt to limit the liability of the owner toclaims for extensions of time and consequently cost claimsby the contractor. Even worse, if the delay, for instancethe owner delays obtaining a building approval, continuesfor longer than 5 working days, then every 5th workingday the contractor must re-apply for an extension of timegiving the details and the adjustment the contractor isaccordingly seeking. This must be repeated until theapproval is given.

One can't but reach the conclusion that theprovisions for strict notification every 5 days is designedsolely to limit the owner's liability. There also seems tobe no logical reason why the contractor should have tocontinue to apply every 5 working days if it is apparentthat the building approval has not been obtained by theowner.

Presumably, the RAIA will contend such shortnotice periods are necessary to ensure the contractoradministers the contract efficiently and that the owner hasearly notice of any claim being made, along the linesrecommended by Paper No.9 of "No Dispute". "NoDispute", however, recommended 7 days' notice ofintention to claim and 28 days' notice from the initialnotification of the claim (Le. 35 days) (see paragraphs 3.5and 3.7 on page 165 of "No Dispute"). This is a far cryfrom 2 working days and 3 working days (Le. 5 workingdays) as required by CIC-l. If the reason is efficientadministration, why didn't the RAIA require the architectto assess the contractor's claim in a similarly short period,e.g. 5 working days, and further provide that failure toassess within that time will result in a deemed assessment

ACLN - Issue#S7

either of time or money as claimed by the contractor. Thiswould accord with the consequence of the architect'sfailure to assess time within the stipulated period as alreadyexists in clause 9.04 of JCC. This would also reallyfacilitate efficient administration of all claims and makeCIC-l 's abnormally short time periods applicable to bothparties. The document would at least be equitable, if notfair.

The requirement of the contractor to re-apply every5th working day is compounded by the fact that thecontract doesn't specify any time within which thearchitect is to deal with the application for an extensionof time. The clause says that the architect must promptly(does this mean immediately?) assess the contractor'sclaim (clause 112) and if the architect believes that thecontractor is entitled to an adjustment to the date forpractical completion the architect must issue to thecontractor and to the owner its written decision specifyingthe adjustment (clause JI3). There is no requirement asto when this notice to the contractor and the owner is tobe given and one can only assume it must be done within areasonable time ofpromptly assessing the contractor's claim.

The contract is silent as to what happens if thearchitect fails promptly either to assess the claim or tonotify the contractor and the owner of the adjustment.Presumably the owner is then in breach of contract whichthen triggers the requirement for a further notice from thecontractor which must also be given within 5 workingdays if a claim is to be made for damages for breach ofcontract. The document appears to attempt to limit thecontractor's rights at every possible opportunity byimposing strict time limits on the contractorif it wants tomake anything other than a normal progress claim.

It might be added that these strict time limits evenextend to claiming for variations which have beenspecifically instructed by the architect! So much forAbrahamson and "No Dispute"!

The RAIA's assertion that this document is fair andequitable is, with respect, nonsense. The draconian timelimits apply only against the contractor. There are nospecified time requirements at all imposed on the architect(one notes it is an RAIA document) or on the owner exceptin respect to progress and final certificates and theirpayment. Nor indeed is there any requirement for theowner to give any notice if it wishes to make claims underthe contract against the contractor. The owner merelynotifies the architect accordingly and if the owner is soentitled to the claim, the architect is obliged to make thenecessary adjustment in the next certificate.

There is perhaps a further shortcoming for thecontractor in clause J2 in that the only primary obligationof the owner under Section A Overview is to pay thecontractor. There is no fundamental obligation on theowner to give access to and then possession of the site tothe contractor as one would expect as contained in clause1.04 of the ICC documents (1994 edition).

The provision concerning access to the site iscontained in clause Fl but there, the owner only must givethe contractor access to the site not possession of the site.

9

This is presumably to complement the owner's rightsunder Section G 19 to engage separate contractors forspecialist works. The contractor under Section G 20 hasan obligation to co-operate with any separate contractorand must give the separate contractor access to the siteand information relating to the working conditions of thesite to enable the separate contractor to make anappropriate allowance in its pricing and to plan itsactivities! !

Whilst the contractor has some rights in relation toclaims for any loss, expense or damage which results froman act or omission of a separate contractor, beyond thatwhich "... a reasonably competent contractor might haveanticipated having regard to the contract documents ..."there are once again draconian time limits imposed on thecontractor for making such a claim in that the initial noticeofclaim must be given within 5 working days ofbecomingaware of the (separate) contractor's act or omission andthe contractor must, within 15 working days of becomingaware of "the (separate) contractor's the (sic) act oromission" give details of its claim which must also includeany extra costs resulting from the impact of the act oromission on the contractor's ability to bring the works topractical completion by the date for practical completionas adjusted, as well as the loss, expense or damage whichresults from the act or omission of the separate contractor.How the ordinary contractor is to know all these thingswithin such a short time is beyond comprehension.

Again, the only conclusion that can be drawn as tothe purpose for these strict time and other requirementsfor notice is that they are designed solely to restrict thecontractor's claims and thereby limit the owner's liabilityfor such claims. They cannot be conducive to efficiencyand are likely to lead to an ever escalating paper war.

CiauseA3There are commendable provisions relating to the

architect's duties to administer the contract firstly as agentand secondly as assessor, and when acting as assessor, toact independently. By clause 3.2, the owner must alsoensure that the architect in acting as assessor, valuer orcertifier complies with the contract and acts fairly andimpartially, having regard to the interest ofboth the ownerand the contractor and the owner must not compromisethe architect's independence in acting as assessor, valueror certifier. However, the document is deficient in· thatthe owner does not have to ensure that at all times therewill be an architect to administer the contract.Furthermore, the dismissal of the architect and his nonreplacement is not a substantial breach of contract norindeed any failure by the owner to ensure the architectacts independently etc. as specified in this clause. Thedeficiencies in Section L, the termination clause, as itapplies to the contractor are such that it is doubtful if thecontractor has separate common law rights to claim thatthis is a common law breach of contract given that thesecommon law rights do not appear to be preserved by clauseL17. That clause provides that the only ground fortermination that the contractor has are a failure by the

ACLN - Issue # 57

owner to make a progress payment on time or for theowner's insolvency. There is no express reservation ofthe contractor's right to terminate at common law - thismatter should have been clarified in clauses L17 to L23.

It could be devastating for the contractor if thearchitect was sacked immediately before a progresscertificate became due because then it could be argued bythe owner that there was in fact no provision for a progresspayment to become due until the certificate was issued,yet no certificate could be issued since there was noarchitect. There is no fall back provision in clauses K9and K10 that in the event of there being no certificateissued within a specific time, then the contractor's claimis to be paid (see for instance AS2124-1992 clause 42.1and AS4000-1997 clause 37.2). This deficiency appearsto leave the contractor in the wilderness as far as enforcingits right to payment where the architect has been sacked.It seems to be a breach of contract but what can thecontractor do about it? A claim for damages appears theonly remedy, not much consolation for the poor unpaidcontractor.

It will no doubt need to be resolved by a courtwhether the contractor does have common law rights inthis event, but one would have thought the contract wouldhave made provision for this eventuality in order to avoidthe necessity for such legal action. That is, after all, theprime purpose of having a detailed written contract in thefirst place.

Knowing the attitude of some private owners inrelation to how they regard their obligations concerningpayment, these deficiencies could be extremely prejudicialto a contractor.

To some extent, the contract suffers from the sameshortcomings as the JCC form of contract where similarconsiderations apply if the architect is dismissed.

Perhaps under CIC-l the problem is even more acutebecause the role of the architect is even more crucial underCIC-l than it is perhaps under JCC in relation toassessment and certification; especially when the ownerhas the right to terminate for its own convenience underclause L12 and the contractor's claims, if the contract isterminated at will, are entirely dependent upon thecontractual provisions authorising the architect to makeassessments of what is due to the contractor at thatparticular time. If at the time the contract is terminated atthe convenience of the owner under clause L12 and at thesame time the owner dismisses the architect, it seems thatthe contractor is powerless to make any claims at all or atleast to recover such claims other than by legal actionwhich would need also to clarify whether the contractorhas any such rights of recovery.

Indeed if the owner terminates the contract at itssole discretion under clause L12, whilst the contractor isentitled to certain payments under clause L13, there arecertain conditions precedent for the contractor to make aclaim in respect of termination in that it must notify thearchitect (if he is still appointed) within 5 working daysof the termination that the contractor intends to make aclaim, and it must specify in writing details of its claim

10

within 15 working days of the termination. Under clauseLIS, the architect is then to assess the claim promptly andif the architect decides that the contractor is entitled to asum under clause L13, the architect must as soon aspossible issue to the contractor and the owner a certificatespecifying the amount. The owner under clause L16 mustpay that amount within 10 working days after receivingthe certificate.

All this could be inoperative if the owner decides tosack the architect. It seems difficult to comprehend howthe contractor can make claims against the owner if thearchitect is dismissed, given that it appears it is not afundamental breach of contract to have terminated thecontract for the owner's own convenience.

This will no doubt be a fruitful source of incomefor many construction lawyers in the future, if these powersare exercised by an owner in this way.

Section B - DocumentsThe Contract contains an order of precedence of

documents in clause B2. It suffers from the samedeficiency as the CJ form of contract in that "any otherdocument" specified in Schedule 3 will be lowest in theorder of precedence unless the parties provide otherwise.It is submitted that often these documents are specificdocuments dealing with specific requirements of thecontract and may be in conflict with general conditions ofcontract or even the specification and drawings and,therefore, should properly be higher in the order orprecedence. There is no warning note in CIC-l, especiallyin Schedule 3 (as there is in the Appendix to JCC) for theparties to be aware of this and to alter the order ofprecedence accordingly.

Furthermore, Schedule 3 (which deals withspecification for the works, drawings for the works andother documents), does not give any warning about theorder of precedence in clause B2 which is only referredto by a cross reference at the top ofSchedule 3. It is unclear,for instance, if the parties decide to put the other documentsfirst on this Schedule 3, whether that in itself constitutesa different order of precedence for the purpose of clauseB2. It is submitted that that is not enough - the partieswould have to include a special condition altering the orderof precedence so that the documents listed in the order inwhich they are in the Schedule 3 have the order ofprecedence in which they are listed. Unless the parties dothis, then clause B2 appears automatically to mean thatthe specifications have precedence over the drawings andthe drawings have precedence over the other documents,irrespective as to the order in which they are set out inSchedule 3.

The provision relating to a different order ofprecedence of the documents in Schedule 3 is notovercome by subclauses B2.1, B2.2 and B2.3 becausethose provisions only provide that the order ofprecedenceof the specifications is in the order in which they are setout in Schedule 3, the order ofprecedence of the drawingsis the order in which they are set out in Schedule 3, andthe order of precedence of other documents is the order

ACLN - Issue # 57

of precedence in which they are set out in Schedule 3.Clause B2 is silent as to what happens if the documentsset out in Schedule 3 are different to the order ofdocumentsin clause B2.

Even more disastrous for the parties' specificintentions is subclause B2.2. It states that the order ofprecedence of the drawings is the order in which they areset out in Schedule 3. The architect will most likely listthe drawings in numerical order Dl, D2, D3, etc., whichmeans by subclause B2.2 they automatically have thatorder of precedence. It is not uncommon for the firstdrawing prepared to be a scale drawing of the site or theproject overall. If this is listed first, it will automaticallyhave precedence over any detailed drawing listed later,often with disastrous and unintended consequences forthe unsuspecting parties. Will an adversely affected partyhave a right of action against the architect who listsdrawings or other documents as a matter of usual practicein numerical order, if that creates inconsistencies leading tounintended results and possible claims by the other party?

Furthermore, the contractor is not entitled to recoverany loss, expense or damage from an instruction by thearchitect to resolve a discrepancy in accordance with theorder of precedence but, if the instruction is not inaccordance with the order of precedence then thecontractor is entitled to claim a variation. In the examplegiven above, this means that if the architect has listed thedrawings in numerical order and they have that order ofprecedence because of subclause B2.2. Then, if thearchitect later instructs the contractor to follow the detaileddrawings rather than the general scaled plan listed first,the unsuspecting owner may be exposed to a claim for avariation.

For the contractor, this sounds fine until one gets tothe variation clause and realises that in order to claim thevariation, the contractor has to comply with the conditionsprecedent in clause H5 by first of all giving an intentionto make a claim within 5 working days after receiving theinstruction and then, within 15 working days of receivingthe instruction, giving details of the claim (unless theinstruction specifies a different number of working dayswhich of course may be less than 15 working days). Thecontractor can only claim the cost of the variation togetherwith any costs resulting from the impact of the architect'sinstruction on the contractor's ability to bring the worksto practical completion by the date for practical completionas adjusted. It is curious that in other areas of the contract,the contractor is entitled to the loss, expense and damageit suffers but does not have this entitlement in relation toa direction to resolve a discrepancy between documentslisted differently to the order of precedence contained inclause B2 and Schedule 3. Why this anomaly occurs isnot clear.

The RAIA, as already pointed out, has extolled thiscontract as complying with the Abrahamson principlesthat a party should bear a risk where that risk is withinthat party's control. However, clause B4 seems tocontravene this principle because the contractor mustexamine the contract documents before executing this

11

Contract and takes the risk that the "constructiondocuments" accurately describe the works. The"construction documents" mean the specifications shownin Schedule 3, the drawings for the works in Schedule 3and any other documents specified in Schedule 3. Thecontractor is obliged to inspect these constructiondocuments and takes the risk that these constructiondocuments accurately describe the works, even thoughthey are prepared for the owner and, normally, anydiscrepancy etc. in them should be borne by the owner underthe Abrahamson principle quoted above by the RAIA.

It is also important to note that the contractor, underthe very last provision of Section M Miscellaneous clauseMI9, has an obligation to comply with the law and,therefore, must comply with any requirement under anylegislation, regulations, orders, codes and ordinances ofrelevant government authorities applicable to the worksunder this Contract. Furthermore, where Australianstandards apply, MI9 provides that the contractor mustcomply with them unless required by the contractdocuments to comply with a higher standard. These twoprovisions in effect mean that the contractor takes the riskthat the construction documents prepared by the owner(through its architect) might not comply with the law orAustralian Standards. Suppose the designer has describedthe works in the specification or in the drawings designedthe works, which do not comply with the requirements ofthe law or an Australian Standard. Under the Abrahamsonprinciples, that risk would be a risk borne by the owner,as those documents were prepared on behalf of the ownerand the risk in those documents should lie with the owner.The effect, however, of clauses B4 and MI9 means thatthe contractor bears this risk, not the owner. Even theDefence Head Contract doesn't transfer this risk to thecontractor!

Section C - SecurityThe Contract provides only for the contractor to

provide security which may be in the form of a bankguarantee or in the form of cash retention. The clausegenerally is satisfactory in respect to the contractorproviding security but given this is supposed to be a ''fairand equitable" document, why no provisions for the ownerto give security? The fact that the owner rarely agrees toprovide security is irrelevant - the fact there is no provisionfor security by the owner is a further demonstration that theRAJA has prepared the document solely for owners to use.

The contractor has the right at any time to swapcash retention for bank guarantees and vice versa.Furthermore, the owner is to hold moneys on cash astrustee and before the owner can draw on security it mustmake a statutory declaration stating the basis and extentof its entitlement to draw the security. The Contract issilent as to the rights of the contractor if a false statutorydeclaration is made but at least there is a breach of thelaw in making a false declaration. Presumably, one wouldhope that the architect would ensure that the owner does notunjustifiably call on security when it is not entitled to it.

There is no provision, however, for a period of time

ACLN - Issue # 57

to expire before the owner can have recourse to security.The moment the owner gives the statutory declaration tothe contractor and the architect, the owner mayimmediately appropriate the cash retention or make ademand on the bank guarantee. In relation to the bankguarantee, the owner must give the bank a statutorydeclaration and a written demand for payment. It doesn'tprovide, however, that must be given after it has givenboth the contractor and the architect a copy of the statutorydeclaration of the demand for payment. Presumably theowner could make the demand for payment on the bank,obtain the payment and then give the contractor andarchitect a copy of the statutory declaration and thedemand but it is then too late for the contractor to takeany protective measures which presumably was thepurpose of requiring a statutory declaration in thedocument in the first place. This is yet another anomalydetrimental to the contractor's interest.

There is also a provision for a statutory declarationby the owner, if the owner refuses or persistently fails torelease security on practical completion or on a finalcertificate although there is no provision in the contractas to the consequence ofmaking that statutory declaration.Presumably it leaves the contractor to take whatever rightsit has under the contract to seek payment, notwithstandingthe statutory declaration.

Section 0 - LiabilityThe explanatory Memorandum accompanying the

Order Form for CIC-1 states the following:"The contract and in particular the liability andinsurance clauses have been drafted as far aspossible to adhere to the widely acceptedAbrahamson principles that 'risks should lie withthe party most able to control them'."

It is ironical that the RAIA has sought to identifythe liability clause as one which best adheres to theAbrahamson principle. In fact, the absolute opposite isthe situation. This Section D not only does not complywith the Abrahamson principle but could be an absolutedisaster for both contractor and owner depending on whenthe loss or damage occurs. No contractor should ever enterinto a contract with a liability clause as it is contained inSection D. Indeed in relation to clause D1 - Risk ofpersonal ip.jury or death - no owner should ever enter intothis contract either, because if the owner in any waycontributes to the event which causes personal injury ordeath, that contributory negligence of the owner willprobably negate the liability of the contractor for thepersonal injury and death (see AMF International vMagnet Bowling (1968) 2 AER 789). This probably alsoapplies if a separate contractor contributes to that personalinjury or death. Again, the contractor's liability to bearthe risk of that personal injury or death to any person onthe site would also probably be negated.

Subclause D1.1 curiously then provides that theowner takes the risk immediately after the notice ofpractical completion is issued to the contractor and theowner, although "this clause" (presumably the whole of

12

clause 1, or does it mean only clause 1.1 - this is not clearbecause "clause" is not defined - does it include or exclude"subclause"?) does not release the contractor from anyliability for death or personal injury that arises from thenegligence of or breach of contract by the contractor orany of the contractor's employees, agents orsubcontractors. Given that the contractor's employees,agents or subcontractors could never be in breach of thiscontract as they are not parties to it, the wording is curious.It also means that the contractor bears no responsibilityduring the defects liability period whilst it is on site, butthe owner solely bears that risk. For the owner to escapethis risk, it must prove that it is negligence or breach ofcontract by the contractor or the contractor's employees,agents or subcontractors that has caused the personalinjury, loss or death. This may be difficult to prove incertain circumstances.

The reason why no owner should accept this clauseis that any contributory negligence by the principal will,as explained above, probably negate the contractor'sliability to bear the risk up to practical completion. Thiswhole clause is a minefield insofar as liability is concerned.

Clause D2 is even worse as far as the contractor isconcerned. The contractor bears the sole risk of loss anddamage to the works, materials and equipment on site tobe incorporated into the works, plants, tools and equipmentused on site. Consequently, if the loss or damage to theworks is in any way contributed to by the owner orsomeone for whom the owner is responsible, the contractorstill bears the total risk of the loss and damage andfurthermore, has to promptly reinstate regardless,notwithstanding the owner's partial or even totalresponsibility for the loss or damage. In other words, thecontractor takes the risk that the insurer will not meet theclaim for the loss or damage despite the owner's partialor whole contribution to the loss or damage. Worse still,the contractor also solely bears the loss if there is anyshortfall in the insurance payout compared with the costof reinstatement. This is all a complete negation of theAbrahamson principle because the owner in this instanceis not bearing any risk even though that risk or part of it iswithin its control and the loss or damage has been partiallyor wholly caused by it. A contractor should not enter intoa contract with this clause in the contract. Contractorsmust qualify their tenders when this contract is called forby requiring that, for instance, clauses similar to clauses14 and 15 of AS4000-1997 replace section D.

Subclause D.1.2 doesn't assist the owner in relationto loss or damage to the works during the defects liabilityperiod when there is loss or damage to the works causedby the contractor but which is not caused by the negligenceor breach of contract of the contractor or any of thecontractor's employees, agents or subcontractors (which,as pointed out earlier, may be difficult to prove).

The risk allocation in the whole section is totallycontrary to the Abrahamson principle and may severelyprejudice both the contractor or the owner in particularcircumstances.

In relation to the reinstatement clause (clause D4),it is noted that the wording in relation to the reinstatement

ACLN - Issue # 57

obligation of the contractor changes from "negligence ofor breach of contract" by the contractor to its "act oromission". Why is different wording used? It is confusingand inconsistent.

Section E -InsuranceIt is noted that the contractor's obligation to take

out contract works insurance ends once the notice ofpractical completion has been issued for the whole of theworks. Why isn't the contractor liable to maintain contractworks insurance during the period of the defects liabilityperiod in relation to its obligation to effect defectrectification during the defect liability period. Owners mustensure their policy covers this risk. This appears to be adeficiency in the clause from the owner's point of view.

In clause E4, why is it that the contractor's contractwork insurance and public liability insurance must eachcover not only the owner, the architect, the contractor andeach subcontractor and any person for whom the contractoris responsible, but each separate contractor? Won't eachseparate contractor have a similar obligation to take outcontract works insurance and public liability insuranceunder its contract with the principal? In which case, therewill be double insurance whenever there is a separatecontractor.

Clause E5 also seems to be defective in that, whilstthe contractor is required to cover additional consultants'fees relating to the reinstatement or replacement,demolition and removal of debris and reasonable amountsfor inflation, there is nowhere in the contract for theseamounts to be prescribed. Is the contractor required tohave a policy to cover all these items irrespective of theiramount?

Clause E9 dealing with claims when the owner ison risk requires the contcactor to make claims within 5days of the loss or damage and that requirement is acondition precedent to making the claim for that paymentfor the value of lost or damaged items suffered by thecontractor. What happens if the contractor is not awareof the loss or damage - does the 5 day period continue torun notwithstanding, or does the 5 days not start until itbecomes aware of the loss or damage? The wording"within 5 working days of the event giving rise to theclaim" does not import any necessity for the contractor tobe aware of the event before time starts running againstthe contractor.

The contractor also has the right to make a claimunder clause EIO for lost or damaged items. Thecontractor again has to make the claim within 5 workingdays of "the loss or damage" even if the contractor isunaware when that occurred, so it may be unable to claimif it does not discover the loss or damage immediately.The contractor also is required, under clause E11, within15 working days of the loss or damage, to specify detailsof its claim. It is noted that the architect is to make acertificate that the contractor is entitled to a claim if thatis in fact the case and to issue a certificate specifying anamount. However, there is no specific obligation on thearchitect to include that amount in the next certificate.Presumably, it is left to the contractor to make a claim in

13

the next progress claim for that amount so certified. It iscurious that this clause does not follow the usual procedureunder the contract that the adjustment of the contract sumis automatically to be reflected in the next certificate (seefor instance clause 023).

Section F - The SiteUnder clause FI, the owner's obligation is only to

give the contractor access to the site, rather than possessionof the site. This will seriously impede the contractor'srights to exclude persons who have no right to be on thesite, as the contractor does not have possession of the sitein order to assert the usual rights of possession that onemust have when seeking to exclude persons who are notauthorised to be on site.

Clauses F3 through to FII deal with site informationand latent conditions. Clause F3 includes a warranty bythe owner that it has given the contractor all relevantinformation in its possession regarding the site and thephysical conditions on the site. The site information isidentified in Schedule 4. However, having warranted thatall that information is given, clause F4 negates thewarranty because it then states that the site informationprovided "is only to assist the contractor and does notform part of the contract". Furthermore, it is thecontractor's responsibility to have checked the siteinformation before executing the contract. However, thewarranty contained in clause F3 can only operate as fromthe time the contract is entered into. The contract is silentabout what happens if the owner does not provide the siteinformation until after the contract is entered into. Howis the contractor to have checked the site informationbefore executing the contract?

Even worse, under clause F4.I, the owner is notliable to the contractor for loss, expense or damageresulting from any inaccuracy or omission in theinformation the owner has provided. This is outrageousin the sense that the owner does not bear the risk ofinaccurate or omitted information it provides itself. Thisseeks to transfer to the contractor a risk which it cannotpossibly control if the owner is the only person who isprivy to that particular knowledge concerning the site. Thisis also exacerbated by clause M13 which provides that:

"This contract contains everything the owner orarchitect has agreed with the contractor in relationto the matters it deals with and the contractor cannotrely on any earlier contract or anything else saidor done by the owner or architect ... before thiscontract was entered into."

Even worse still, the contractor must indemnify theowner against any claim by a subcontractor or anyoneelse in respect of loss, expense or damage incurred as aresult of the contractor failing to check the site informationas required by clause 4, even though it is inaccurate orhas been omitted by the owner. This again is an outrageousindemnification the contractor has to provide and seemsto fly in the face of the Abrahamson principle that theRAI1\. contends applies to this document. Furthermore,under clause F5, it is the contractor's responsibility to have

ACLN - Issue # 57

thoroughly investigated the site before executing thecontract. It is then and only then that, if the contractorbecomes aware of a latent condition which "a reasonablycompetent contractor" would not have anticipated if thecontractor had checked the site information and thoroughlyinvestigated the site before executing the contract (eventhough that site information might be inaccurate or omitother matters), the contractor is entitled to recompense.

Also, "reasonably" is ambiguous - does it mean"reasonable" or is a "reasonably competent contractor"something less than a competent contractor?

This clause appears to limit the owner's liability forany inaccurate information it supplies, if the contractorcould possibly have found out that information by makingother enquires and thoroughly investigating the site. Thisis compounded by the fact that, if the contractor does claimfor a latent condition, it must at the same time as seekinginstructions once it has discovered the latent condition,also give notice to the architect of its intention to make aclaim for a latent condition. And then, within 15 workingdays after becoming aware of the existence of the latentcondition or receiving an architect's instruction, whicheveris the later, the contractor must make a detailed claim forthe loss, expense and damage it has suffered and alsoinclude in that claim any extra costs resulting from theimpact of the latent condition or the instruction on thecontractor's ability to bring the works to practicalcompletion by the date for practical completion. Theserequirements are also conditions precedent to entitlement.

This cost eventually gets adjusted as though it werea variation under clause H9. However, under clause JI0,the contractor must also within 2 working days haveapplied for an extension of time and within 5 workingdays provided details of the amount being claimed andthen every 5th day repeat the application during the periodof the delay. The amount of paper the contractor mustgenerate under the contract should keep the paper industryin this country particularly buoyant!

Whilst it is fair to say that the contractor has a rightto a latent condition, the restrictions on the claim by virtueof the provisions ofclause F4, especially clause F4.1, makethe right an illusory one.

Section F also deals with the discovery of valuableminerals, money, treasure, fossils etc., on the site. Againthe contractor must within 5 working days after thediscovery of these things, seek instructions and at the sametime give its intention to make a claim under clause F15for an adjustment to the contract sum. Again these areconditions precedent to the claim for an adjustment forloss, expense or damage plus any extra costs caused bydelay. Again, it will be a variation once the architect hasassessed it.

Section G - Building the WorksIt is noted that the owner has no obligation (nor has

the architect) to provide setting out information to enablethe contractor to set out the works. However, thecontractor is required to set out the works and have thesetting out certified by a qualified surveyor. Surely the

14

risk of set out should be borne by the owner given that theowner owns the site and is designing the works.

The contractor is also required within 10 workingdays after being given access to the site, to provide aprogram which is not to be part of the contract. If thereare instructions to amend a program, the contractor isentitled to make a claim for resultant loss, or damage butit is again a condition precedent to making that claim thatwithin 5 working days after receiving the instruction, thecontractor has given notice of intention to make the claimand within 15 working days after receiving the instruction,provide details of its claim. This time it is not a variationbut an adjustment to the contract sum to be reflected inthe next certificate after the architect has assessed theclaim. There is, however, no provision for payment ofextra costs due to delay in completion due to the amendedprogram.

Clauses GI0 to G14 also deal with suspension ofthe works. Once again, it is a condition precedent to makea claim within 5 working days after receiving theinstruction and to give details of the claim within 15working days after receiving the instruction. Opening upand testing of the works has the same conditions precedentapplicable. Clauses G19 to G22 deal with the right of theowner to engage separate contractors for specialist worksabout which comment has already been made.

Section H - Variation to the WorksClause HI gives very wide powers to the architect

to direct a variation to the works. Whilst no variation willinvalidate this contract, the architect does appear to havepower to instruct a variation which is a change to the scopeof the works, which seems to be wider than the usualvariation power in a contract that a variation shall not bebeyond the scope of the works. Does the architect's powerto give a variation to change the scope of the works meanthat the architect may give a variation which is beyondthe scope of the works?

The contractor, if given a variation, mustimmediately start keeping detailed records of the work ofthe variation until such time as the parties have agreed onthe cost in which event the contractor can then stop keepingthe detailed records. However, in relation to a claim for avariation, again it is a condition precedent that thecontractor must within 5 working days after receiving theinstruction give intention to make a claim for the variationand within 15 working days provide details to the architectof that claim.

The claim must also include any time delay costs.Even though the contractor must make these claims withinthe specified time of receiving the initial instruction, thecontractor cannot commence the varied work until givena written instruction "to proceed". Presumably, this is asecond instruction which will often mean the contractor'sclaim for the variation must be lodged before the variationis authorised to proceed. How can the contractor assessits claim and costs, especially time related costs, whenthe instruction to proceed has not even then been given?The contractor is not permitted to proceed, until the

ACLN - Issue # 57

architect has given a written instruction to proceed, unlessthe architect has given a verbal instruction because it isnot reasonably possible to give the instruction in writingbecause of urgent circumstances. It would be rare whenthis would occur and so the contractor really must notproceed with any variation until he has the writteninstruction to proceed. Yet, it may be precluded by theconditions precedent from recovering any claim for thevariation before the instruction to proceed is given.

There is some relief to the contractor in clause HIDin that, if a claim is not made, the architect may still makean adjustment to the contract sum in the absence of a claim- presumably, to ensure that no claims, for instance forunjust enrichment, can be made at a later date. If thearchitect fails to exercise this power, the contractor's onlyrecourse is to claim unjust enrichment or other similarcommon law remedies which CIC-l attempts to excludein any event, so recovery may be difficult.

Section J - Completion of the WorksThis section deals firstly with practical completion

and then deals with other issues which occur during thecourse of the works before practical completion. It seemsunusual that the clause deals with practical completionfirst and deals, for instance, with extensions of time forpractical completion at a later stage in the clause.

Notification of practical completion does not incuruntil the contractor considers the works have reachedpractical completion, i.e. after the event. There is norequirement for the contractor to give advance notice ofwhen he might reach practical completion. The conceptof practical completion appears to be defined in effect inclause Jl.

Under clause J7, the owner has the right to takepossession ofpart of the works before practical completionof the whole of the works. If that is required, there is to bediscussion between the architect and the contractor aboutbreaking the work down into separable parts and ifagreement cannot be reached, the architect may aftergiving 48 hours' written notice to both the contractor andthe owner may give notice that the works have been brokendown into separable parts. There is no separate right ofthe contractor to claim a delay to the completion of theremaining works if that is delayed by the occupation ofthe separable parts by the owner and, given that the ownerhas the right to occupy the separable parts, such delaycannot be a breach of the contract by the owner undercause J16 in clause JI0, although it may possibly be anact of prevention by the owner not otherwise covered byclause J 10 under cause 19, or an event not in thecontemplation of the parties at the time the contract wasexecuted under cause 17. However, in this latter event,the contractor is not entitled to adjustment of time costsalthough it is entitled to costs if it is shown to be an act ofprevention by the owner.

In relation to applications for extensions of time,there are some 19 separate causes of delay in clause JI0for which an extension of time may be granted.

The draconian provisions concerning notice have

15

already been noted. The original notice to claim theextension of time must be given within 2 working daysafter the contractor becomes aware of the cause of thedelay and the contractor must then in writing specifydetails of the circumstances and the adjustment thecontractor is seeking to the date for practical completionwithin 5 working days after becoming aware of thecircumstances giving rise to the claim and repeat thatapplication every 5th working day during the whole periodof the delay. To miss one such notice will deny thecontractor the right to an extension of time from the endof the previous notice period.

It is submitted that clause J12 dealing with thearchitect's right to assess the claim may cause difficultiesfor the owner where the act of delay occurs after the thendate for practical completion and between that date andthe date of practical completion. It is unclear whetherwhat would otherwise be an act ofprevention by the owneris catered for by the contract. Notwithstanding the factthat clause J10, cause 19, deals with an act of preventionnot otherwise covered by the clause, the architect'sentitlement to extend time under clause J12 is as follows:

"The architect may only allow the claim to the extentthat the contractor's ability to complete the worksby the date for practical completion (as previouslyadjusted) is affected."

It is unclear whether this provision is wide enoughto enable the architect to deal with an application for anextension of time after the adjusted date for practicalcompletion and before the date of practical completionand if so, how the architect so adjusts the date for practicalcompletion accordingly.

Presumably clause J14 may assist in that thearchitect does have power to adjust the date for practicalcompletion, even if the contractor has not made a claimfor an adjustment, at any time up to the issuing of thefinal certificate under clause K13 or a certificate underany of the clauses LID, L15 or L23.

Clause J16 - Liquidated DamagesIf liquidated damages are deducted (in fact adjusted

in a certificate once the owner notifies the architect itwishes to enforce liquidated damages) and subsequentlyan extension of time is granted, the owner's obligation isnot to immediately repay the liquidated damages deducted.Instead, the architect is required to include the adjustmentin the next certificate. Therefore, if for instance, thearchitect subsequently adjusts the date for practicalcompletion after the date ofpractical completion, becausethere is no right for the contractor to make a furtherprogress claim until the final payment claim at the end ofthe defects liability period, this means that the contractorcannot recover an adjustment of the liquidated damagesuntil that final certificate is issued. In this respect theclause is unsatisfactory because there is no obligation onthe owner to repay those liquidated damages forthwith,rather than in the next certificate (i.e. the final certificatein these circumstances).

ACLN - Issue # 57

Clause J18 deals with the contractor's right to claiman adjustment for time costs which are described as "loss,expense or damage". This is curious because, elsewherein the contract, where the contractor has to make a claimfor an adjustment of time costs, they are described as "extracosts incurred by the contractor" resulting from the impacton the contractor's ability to bring the works to practicalcompletion. The concept of"loss, expense or damage" isfar more generous to the contractor than "extra costs" are.Furthermore, the parties have the right in the Annexure tolimit the contractor's right to recover adjustment of timecosts to a set figure per day or per week. If that has beendone, the contractor must realise that not only does itrestrict its right to costs for delaying events set out in:

• cause 2 of clause JI0 ("ownerfailing to giveaccess to the site on the date referred to inclause FI");

• cause 12 of JI0 ("the owner's consultantsfailing promptly to provide necessaryinformation to the contractor which thecontractor has specifically requested inwriting.");

• cause 15 of JI0 ("a suspension of the worksunder clause L18" due to the owner'sdefault); and

• cause 19 of JI0 ("an act of prevention bythe owner not otherwise covered by thisclause"),

but it also covers cause 16 ("a breach of this contract bythe owner").

The contractor, therefore, appears to have noseparate right to claim damages for a breach of contractby the owner which results in delay, but is bound by theamount agreed upon in the Schedule. Again there areconditions precedent to making such claims in that thecontractor at the same time it is applying for an extensionof time must also (i.e. within 2 working days after thecontractor becomes aware of the circumstances giving riseto the claim), also give notice of claim for the delay costs- otherwise it will not be entitled to claim them. Thismeans that the contractor has to continually bombard thearchitect with applications for extension of time whichmust also claim the adjustment of time costs because thecontractor cannot risk inadvertently leaving a claim outof any application should the cause of the delay tum outto be a cause for which adjustment of time costs might bepayable. Once having given that initial 2 working days'notice of the intention of making the claim, the contractormust within a further 15 working days give details of itsclaim. How can it satisfy this requirement if the overalldelay lasts longer than 15 working days?

Section K - Payment for the worksIf the owner sacks the architect, how does the

contractor get paid? Some relief may be thought to havebeen granted by clause Kl which provides that theobligation of the owner is to pay the contract sum adjustedprogressively, but this is to be done in accordance withclause KI0. Clause KI0 triggers the owner's obligation

16

to pay the amount owing in any progress certificate issuedby the architect, which must be paid within 10 workingdays after delivery of the certificate. It is the writer'sview that, if the architect is sacked and there is no architectto issue a progress certificate, there appears to be no waythat the contractor can validly enforce payment.

There being no obligation to pay, it seemsimpossible for the contractor to be able to serve a noticeof default under clause L17 and, given that the contractor'srights to claim for breach of contract at common law doesnot appear to be preserved, the contractor appears to beleft without a clear remedy either at common law orunder the contract. This aspect of CIC-l is totallyunsatisfactory.

Clause K5 deals with provisional sums. This allowsthe architect at its sole discretion to give an instruction toa person other than the contractor to perform work or tosupply or install an item for which a provisional sum isallowed. That person automatically becomes asubcontractor to the contractor but, if the contractorsufficiently complains about accepting that person as asubcontractor under clause 5.1, then that person willbecome a separate contractor and the contractor is obligedto assume the duties under clause G20 in relation to thatperson and clauses G21, G22 and G23 will apply. Thisappears to be a device to allow nomination without givingthe contractor any rights to object to that subcontractorand, if the contractor does so, the architect appearsprecluded from naming anyone else to effect theprovisional sum work but must make that subcontractor aseparate contractor. In that event, there appears to be noright on the contractor to have security appropriatelyadjusted, especially if the security is by way of bankguarantee.

Although a provisional sum is to be included in thecontract sum, the contract sum will be adjusted by thearchitect to take into account any difference between theprovisional sum allowance etc. The contract gives anallowance to the contractor of the provisional sumpercentage for profit and overheads stated in item 24 tothe extent that the amount is more than the provisionalsum but, if it is less than the provisional sum, no additionaladjustment is made whether the provisional sum work isdone by a subcontractor or a separate contractor, becauseclause K6 applies when the provisional sum work is doneby a "person other than the contractor", i.e. asubcontractor or separate contractor.

Progress Payments &Progress CertificatesClause K9 requires the architect within 14 working

days after receiving a claim (which must be made by the10th of each month) to issue to the contractor and theowner a progress certificate setting out any payment due.The owner's obligation is then to pay that certificate within10 working days after delivery of the certificate.Consequently the owner has a total of 24 working days tomake payment. This effectively means a minimum of 34calendar days for payment and if the compatiblecompanion subcontract provides for a similar period withan additional period of grace for payment by the main

ACLN - Issue # 57

contractor, the poor subcontractors are not going to bepaid until about 40 calendar days after the claim, if notlonger. Provisions for payment times should be shortenedin this modem age of EFT, not lengthened.

The provisions in relation to final payment claimand final certificate are unobjectionable.

The provision concerning payment of interest onoverdue amounts is commendable in that the interest onlyat the end of each month is to be capitalised and added tothe moneys outstanding.

Section L - Termination of engagementIt is this clause which really highlights the unfair

and inequitable nature of this contract. If ever there was aclause that caters to the owner and is anti-contractor it isthis one. First of all the owner has a total of 13 separateevents for which it may serve a notice to remedy a default.Event 13 allows such a notice "if the contractor breachesany other obligation under this contract". This is so allembracing that just about anything the contractor fails todo under the contract can be the subject of a notice ofdefault under clause L1. This is to be contrasted with thecontractor's extremely restricted right under clause L17in relation to an owner's default. The contractor's onlyright to serve notice ofdefault is if the owner fails to makea progress payment on time.

Both provide for 10 working days' notice i.e.effectively a minimum of 14 calendar days. This isparticularly unfair on the contractor who has to keepworking for those 10 working days whilst not being paidand not knowing whether it is going to be paid. It is onlyuntil the 10 working days have expired and payment hasnot been made that the contractor can then either terminateor suspend.

Furthermore, some of the reasons of default givento the owner are extremely tenuous. For instance, event 7- "the contractorfails to direct the manner ofpeiformanceofthe works". What does this mean? Other vague groundsare - "The contractor fails to supervise the workcompetently", ''fails to maintain a satisfactory health andsafety system on the site", even that the contractor ''failsto ensure that a contractor's representative is appointedat all times".

Why isn't it a corresponding breach that the ownerhas failed to ensure that an architect is employed at alltimes? Section L is very one-sided. It is even worse,given the one-sided nature of this clause, that the owner,once he terminates, is not obliged to make a furtherpayment (even if a payment certificate is then due forpayment) until such time as an obligation arises to payunder clause Lll which provides that once the work hasbeen finished, then the architect is to calculate the balancedue by one party to the other.

Clause L12 compounds the one-sidedness of thisclause in that it gives the owner the right unilaterally toterminate the engagement at its sole discretion withoutany good reason, upon giving the contractor 10 workingdays' written notice. So much for privity of contract!

The contractor has a right to certain payments, ifthe owner terminates the engagement at its sole discretion,

17

but it is again a condition precedent to payment that thecontractor must make the claim within 5 working days ofthe termination and must give details within 15 workingdays of the termination. Once again, this clause appearsmainly designed to inhibit the ability of the contractor tomake claims.

A further problem arises under clauses L20 to L23in that the payment due to the contractor, after terminationby the contractor for the owner's default, is required to becertified by the architect. Given that there is no obligationon the owner to ensure that there is an architect employedat all times during the contract, there is nothing to stopthe owner from also terminating the architect'sappointment at the same time as terminating the contract,in which case there appears to be no provision for thecontractor to recover the moneys by virtue ofan architect'scertificate, because the architect cannot give a certificateonce its engagement has been terminated. Given the nonreservation of the contractor's common law rights, howis the contractor to recover the damages it suffers becauseof the owner's breach of contract?

Section M - MiscellaneousThere are a number of different unrelated topics in

this section.For instance, the dispute resolution clause is

contained in this section. There are also othermiscellaneous provisions concerning intellectual property,quality assurance, service of notices, severability, waiver,governing law, compliance with the law and even that theowner has to pay stamp duty on the agreement. It seemssuch a hotchpotch of clauses that one wonders why someof these topics, particularly the dispute resolution clause,were left in this section and were not made a separatesection.

Clause Ml is a warranty by the contractor that ithas the capacity to enter into the contract and that it hasthe skill, technology, human resources and financialresources necessary to perform its obligations. If thiscontract was really fair and equitable as maintained bythe RAIA, surely there would have been a correspondingwarranty by the owner that it has the financial resourcesnecessary to fund the project and that the project is toproceed. This, after all, was an important part of theAS4120 Code of Tendering which the RAIA supportedwhen it was being prepared. It is surprising that thearchitects did not include this obligation on the owner.Or are they really intent on making this contract so onesided in favour of the owner that they will encourage theowners to use it (and, therefore, use their members asarchitects under this contract) rather than using other fonnsof contract.

There is also a further barring clause tucked awayin clause M6 that the architect's certificate or writtendecision can only be disputed if the contractor gives awritten notice under clause M7 within 15 working daysafter receiving the document or after the failure of thearchitect to issue "something". If the contractor fails togive a notice of dispute, the contractor will not be entitledto dispute the matter at all. This is so one-sided against

ACLN - Issue # 57

the contractor and in favour of the owner that this barringclause is totally unacceptable. Why is it not equallyapplicable to the owner - if the owner wishes to disputethe architect's certificate, assessment, decision, notice, etc.,or failure to issue "something"? Why should not the owneralso be obliged to give a notice of dispute within 15working days? This clause is the final straw so far as theunfairness and inequity of this document is concerned.This is especially so as the time runs from when thearchitect ''fails to do something". If the architect failspromptly to grant an extension of time, when does thetime under clause M6 start to run against the contractor?This clause gives the owner ample opportunity (in additionto all the other conditions precedent running against thecontractor) to raise a time bar against the contractor.Fortunately, the High Court has recently ruled out suchattempts in NPWC3. Hopefully, the same situation appliesto this clause M6.

The dispute resolution clause also appears to beunrestricted in its scope of application. It is not confinedto matters which arise "in connection with contract or itssubject matter". It appears to apply once there is a disputeor difference between the parties about anything. Theclause provides that the representatives of the parties areto meet within 5 days. It does require details of the disputeto be provided with the notice. Given that this notice willdetermine the jurisdiction of any arbitrator to be appointedif the dispute or difference is not settled, how is thatjurisdiction to be defined? The clause is a fertile groundfor disputation itself. The clause provides an option forcourt or arbitration proceedings. Is it intended to be anagreement to arbitrate and it is intended that clause L6will be covered by the PMT Partners case if the notice ofdispute is not given within 15 working days?

It is also noted in clause M11 that the contractor isrequired to observe the confidentiality of informationmarked as "confidential". There is no obligation, however,on the owner not to disclose any confidential informationprovided by the contractor.

Clause M13 attempts to limit the contractor's abilityto use pre-contractual information as a basis for a claim.It provides the contractor cannot rely upon any earliercontract or anything else said or done by the owner orarchitect or by an officer, agent or employee of the owneror architect before this contract was entered into. It onlyapplies to the contractor. Presumably, the owner can usepre-contract information provided by the contractor. Onceagain, CIC-l is one-sided and accordingly unfair andinequitable.

Section N - DefinitionsIt has already been pointed out that there are only 4

definitions in this section:Contract documents;Construction documents;Insolvency event; andIntellectual property.

All the other definitions one has to find within the body ofthe clauses but even where used in the document, any other

18

definition is not distinguished by italics, bold, capitalletters, etc.

The introductory words to clause Nl provide "Thefollowing phrases have the following meanings". Thisstatement is unqualified - does it apply only if the contextrequires it; does it apply to other contract documents suchas the specification? It is totally unclear.

SCHEDULE 1 - CONTRACT INFORMATIONLittle guidance is given in the document as to the

form of the contract information to be provided. Thereare few fall back provisions to guide the parties as to whatthose usual provisions might be. For instance clause M18relates to item 30 of Schedule 1dealing with the governinglaw. What happens if the parties fail to include anyprovision in item 30 of the schedule concerning thegoverning law? There is no fall back position in clauseM18 that, for instance, it will be the law of the site inwhich the works are situated or words to that effect.

CONCLUSIONThe inescapable conclusion that must be reached

from the provisions of the CIC-l document is that it is anattempt by the RAIA to produce a one-sided contract soas to ensure that there is an architect in the contract toadminister it, thereby protecting its members.

CIC-l seems to be only a counter by the RAIA tothe proposed PCA document.

In conclusion, one might refer to the press releaseissued by the RAIA on Tuesday, 14 October 1997 whenthis contract was launched. In that press release, Mr. Peck,the RAIA Chief Executive is quoted as follows:

"In view ofthe failure of the industry to produce astandard form of contract and because thearchitectural professional has no particular biastowards either party in a construction contract, wehave decided to offer to the industry a new plainEnglish contract which we believe has the necessaryproperties offairness and practicality."

Mr. Peck has obviously ignored AS2124-1986,AS2124-1992 and AS4000-1997 which are standard formsof contract produced by the industry by a committee onwhich the RAIA is represented.

AS2124 has been adopted by all governments inAustralia except the Northern Territory. AS2124 and itspredecessors have been in use since the 1920s. It is simplynot correct to suggest the industry has not produced astandard form ofcontract - the statement even contradictsthe RAIA's own promotion of JCC of which it is a jointcopyright holder. The author submits the above commentsamply demonstrate the document has neither fairness norpracticality and certainly fails in a number of importantareas to adhere to the Abrahamson principle of riskallocation which the RAIA says has been the basis of thisdocument.

Of course, in a free market, the RAIA is entitled topublish whatever contracts it wishes. It is an issue for themarket to what extent they are used.