CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE CBO · 2017. 3. 28. · How CBO Estimates...

Transcript of CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES CONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE CBO · 2017. 3. 28. · How CBO Estimates...

CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATESCONGRESSIONAL BUDGET OFFICE

CBOThe Budgetary Effects

of the United States’

Participation in

the International

Monetary Fund

JUNE 2016

© S

hutte

rsto

ck/v

ecto

rEps

10

CBO

Notes

Numbers in the text may not add up to totals because of rounding.

Data underlying the figures are posted along with this report on CBO’s website.

www.cbo.gov/publication/51663

Contents

Summary 1

How Does CBO Account for the United States’ Participation in the IMF in Budget Estimates? 1

Why Is There a Cost Associated With the United States’ Participation in the IMF? 2

How Does CBO Estimate the Fair-Value Cost to the United States of New Commitments to the IMF? 2

Why Does CBO Use a Market-Based Estimate of Cost? 3

How Uncertain is CBO’s Estimate? 3

What Other Effects Does Participation in the IMF Have on the Federal Budget? 4

Background on the International Monetary Fund 4

Membership, Quotas, and Additional Financing Resources 4

Lending Activities 6

The IMF’s Balance Sheet and Reserves 7BOX 1: THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND’S LOANS IN ARREARS 8

The Effects of Large Losses 8

Budgetary Treatment of the United States’ Participation in the IMF 10

CBO’s Current Budgetary Treatment of Commitments Made to the IMF and the Effect of Recent Legislation 10

Past Budgetary Treatment of Commitments Made to the IMF 13

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Current and Past Budgetary Treatments 14

How CBO Estimates the Fair-Value Cost of the United States’ Participation in the IMF 15

Loan Disbursements 17

Scheduled Loan Repayments 17

Loan Losses 17

Income Retained by the IMF 19

Losses Absorbed by the IMF’s Reserves 19

Present-Value Calculations and the Cost of Market Risk 20

Other Effects on the Federal Budget of the United States’ Participation in the IMF 22

Budgetary Effects of Fluctuations in the SDR Exchange Rate and Interest Rate 22

Budgetary Effects of the United States’ Role as a Stakeholder in the IMF 23

Indirect Effects on the Federal Budget of Participating in the IMF 23

List of Tables and Figures 25

About This Document 26

CBO

The Budgetary Effects of the United States’ Participation in the International Monetary Fund

SummarySince 1945, when the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was established to promote global economic cooperation and stability, the United States has been its largest con-tributor. Today, the United States’ financial commitment to the IMF totals approximately $164 billion; that is the maximum amount that the IMF can draw from the United States to make loans to other IMF members.

The budgetary cost of participation in the IMF is, however, significantly smaller than the amount of that commit-ment. The United States and other countries earn interest on the portion of their commitment held by the IMF, and the IMF’s assets, including loans to other members, gold, and financial securities, are sufficient to allow it to return those funds to members in most circumstances. Nevertheless, a small risk remains that the IMF could incur losses on its lending so large that it could not repay the United States the full value of its commitment. Because of that risk, participation in the IMF has a cost to the United States, which the Congressional Budget Office currently estimates to be about 2 cents per dollar committed.

How Does CBO Account for the United States’ Participation in the IMF in Budget Estimates?The nature of the United States’ transactions with the IMF makes accounting for them in the federal budget difficult. When the United States pledges funds to the IMF, it commits to loan up to that specified amount to the organization—that is, it extends a line of credit. Some of the pledged funds are immediately transferred to the IMF, which either invests them in a range of securities or lends them to other members. The IMF can draw on the remainder of the pledged funds as needed for lending; it returns those funds to the United States when the borrowing members repay their loans.

In exchange for the funds that it provides to the IMF, the United States receives special drawing rights (SDRs). The SDR, whose value is based on a basket of widely circulated currencies, serves as the unit of account for the IMF. The United States earns interest on its SDRs and retains the right to withdraw funds from the IMF—that is, to cash in its SDRs at the current SDR exchange rate with the dollar—at any time. Thus, each dollar that the United States commits to the IMF retains value over time, though the exact amount that will be returned depends on the extent of IMF lending, the income that the IMF earns on its investments and lending, how much of that income is passed through to members as interest, and the exchange rate between the SDR and the U.S. dollar.

Since 2009, laws providing for additional U.S. commit-ments to the IMF have specified that the budgetary effects of those commitments be estimated on a fair-value basis—that is, using a present-value amount that is a market-based measure of the net cost of the indefinite commitment of additional funds to the IMF.1 The use of the present-value method reflects the notion that each dollar committed to the IMF retains most of its value for the United States and is not simply a cash expenditure. But the present value of the cost is not zero—as it would be if the commitment had no cost to the federal govern-ment—because the interest that the United States receives on its contributions is not sufficient to fully com-pensate it for the very small risk of catastrophic losses that could occur following large or widespread defaults by IMF borrowers.

1. A present value is a single number that expresses a flow of future income or payments in terms of an equivalent lump sum received or paid at a specific point in time; the present value of a given set of cash flows depends on the rate of interest—known as the discount rate—that is used to translate them into current dollars.

CBO

2 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND JUNE 2016

CBO

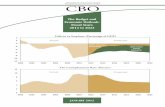

Figure 1.

Components of CBO’s Fair-Value Estimate of the Cost to the United States of New Commitments to the IMFPercentage of New Commitment

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the International Monetary Fund.

IMF= International Monetary Fund.

Cost to the IMF of Its Loans Effect of the IMF’s Reserves Cost to the United States ofNew Commitments to the IMF

-1

0

1

2

3

Why Is There a Cost Associated With the United States’ Participation in the IMF?When the United States makes a deposit with the IMF, the rate of interest that it receives on its SDRs is indexed to the rates available on a basket of low-risk debt. How-ever, deposits with the IMF pose an additional risk beyond that posed by investing directly in a portfolio of low-risk debts of developed countries because some of the value of those deposits may be lost as a result of financial, economic, or political crises that triggered widespread defaults among borrowers of IMF loans. Although the conditions that the IMF imposes on its lending, its de facto seniority in repayment, and its holdings of gold and reserve assets protect members from losses, the possibility of members having to incur large losses on the IMF’s loans remains, though the probability of that happening is very small.

Although the IMF has experienced only negligible losses on its lending to date, global economic circumstances could generate large losses in the future if many IMF bor-rowers were to cease repayment of their loans. In those circumstances, the IMF would not have enough income from its lending and investments to continue paying members interest on their SDR holdings, and the amounts flowing to the United States and other members would be reduced. Any present-value estimate of the

United States’ commitment should therefore reflect the possibility of such a reduction in the future.

How Does CBO Estimate the Fair-Value Cost to the United States of New Commitments to the IMF? To estimate the cost to the United States of new commit-ments to the IMF, CBO first estimates the two compo-nents of that cost: the cost to the IMF of the loans it makes to its members and the effect of the IMF's reserves (see Figure 1).

The cost of the loans that the IMF makes to its members is equal to the present value of the loan amounts dis-bursed minus the principal and interest received on that lending. The IMF charges its borrowers a higher interest rate than the rate it pays to members on their SDR hold-ings. However, CBO estimates that in a crisis in which a large number of borrowers defaulted, the IMF would not receive a significant amount of the scheduled principal and interest payments, which means that the IMF’s lending has a small net cost.

Some of the losses on the IMF’s loans would be absorbed by the organization’s reserves, which would reduce the cost to the United States of its new commitments to the IMF. The IMF adds amounts approximately equal to the income it earns on its loans to its already large

JUNE 2016 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

reserves, which it can use to mitigate losses before they are passed on to its members. CBO estimates that those reserves could absorb a substantial share of the losses that could occur in the future.

To make its projections of those two components of the cost of the United States’ participation in the IMF, CBO uses a probabilistic model to simulate changes in the IMF’s financial assets and liabilities—including inflows and outflows from investments, loans to members, quotas, lines of credit, and operating expenses—under a range of outcomes for loans made by the IMF to member coun-tries. The simulated annual cash flows to and from the U.S. government are expressed as a present value using market-based discount rates.

Why Does CBO Use a Market-Based Estimate of Cost?The use of the fair-value method to estimate the cost of the United States’ commitment to the IMF was estab-lished following consultation with the House and Senate Budget Committees and was the method specified in law the last time legislation affecting the IMF was enacted. CBO has concluded that it would continue to use that approach in analyzing future legislation that provided U.S. funding for the IMF.

Because CBO uses market-based discount rates to com-pute the present value of commitments to the IMF, its estimates include the cost of market risk that is inherent in the IMF’s lending activities. Market risk—the risk that remains even after a portfolio has been diversified as much as possible—arises because most investments tend to perform relatively poorly when the economy is weak and relatively well when the economy is strong. Thus, incorporating the cost of market risk accounts for the fact that losses incurred by the IMF will tend to be largest in those cases in which the global economy is weakest. When the U.S. government takes on market risk, that risk is effectively passed on to private citizens who, as taxpayers and beneficiaries of government programs, bear the con-sequences of the government’s financial losses. Private citizens tend to value their income more highly when the economy is weak than when it is strong, so bearing market risk associated with government programs is costly to them.

CBO accounts for the market risk associated with IMF commitments by using slightly higher discount rates to make the present-value calculations than the market rates of interest on the basket of low-risk debt. The use of higher discount rates for IMF cash flows reflects the fact

that those flows have more market risk than funds invested in a basket of low-risk sovereign debt. CBO determines that discount rate from the market yields of sovereign debt securities with risks comparable to those of loans that would be made by the IMF. Without that adjustment to the discount rate, each additional dollar that the United States committed to the IMF would, CBO estimates, have a budgetary cost of approximately 0.5 cents per dollar committed instead of 2 cents.

Some analysts have expressed concern about using the fair-value approach in federal budgeting. One criticism is that adjusting some programs for market risk but not others might make comparison between programs diffi-cult. Another concern is that changes in the cost of mar-ket risk over time make estimates more volatile. Finally, some critics of fair-value estimates note that such esti-mates are more complex than others and that they are therefore more difficult to communicate to policymakers and the general public.

Proponents of the fair-value approach counter that deci-sions about spending the public’s money should take into account how the public assesses financial risks as expressed through unbiased market prices. They also note that con-cerns about volatility and complexity can be mitigated by using well-developed accounting practices.

How Uncertain is CBO’s Estimate?Although the risk posed by the IMF’s lending strongly suggests that the United States’ participation in the IMF has some budgetary cost, there is a great deal of uncer-tainty about the magnitude of that cost. No market-based financial instrument shares exactly the same risks that are inherent in IMF lending, so there is no comparable data from which the cost of members’ commitments to the IMF could be inferred. There is also no clear historical precedent for an event that would generate losses to the IMF that were significant enough that they would be passed on to the United States; thus, the parameters of such losses are estimated with a large degree of uncertainty.

Those parameters include the frequency, magnitude, and duration of crises extreme enough to bring about a large increase in the IMF’s lending and to cause a significant number of the borrowers to default on those loans. In addition, the terms of those loans (the interest rate paid by borrowers, for example) and the IMF’s reserves affect the value of the United States’ commitment. Finally, the actions of members and other entities may affect the

CBO

4 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND JUNE 2016

CBO

IMF’s finances and thus the value of the United States’ commitment to the organization: Some actions, such as establishing programs to assist borrowing members to repay their IMF loans, might help the IMF’s financial position, but others, such as challenging the priority of the IMF’s claims above those of other debt holders, might hurt it. CBO intends for its estimate of the cost of the United States’ participation to reflect the central estimate of the range of uncertain outcomes for each of those factors.

What Other Effects Does Participation in the IMF Have on the Federal Budget?The United States’ participation in the IMF has potential budgetary effects beyond those incorporated in CBO’s fair-value estimates. Those effects include gains and losses attributable to fluctuations in interest rates and exchange rates, the potential value to the United States of the IMF’s gold and other reserve assets, and the indirect effects on the budget from the IMF’s role in stabilizing the global economy.

Background on the International Monetary FundThe United States is one of 189 member countries that belong to the IMF and further the organization’s mission of promoting financial stability and monetary coopera-tion. When a member country has a large deficit in its balance of payments—that is, when its imports and financial outflows exceed its exports and financial inflows—and it cannot address that problem through regular borrowing, monetary policy, and fiscal measures, it can request a loan or technical assistance from the IMF to help stabilize its currency and improve its economic conditions.

Membership, Quotas, and Additional Financing ResourcesThe lending programs and operations of the IMF are supported by financial contributions made by its member countries. Each country is assigned a quota on the basis of a formula that includes measures of the size, strength, and openness of its economy; that quota represents the country’s primary financial commitment to the IMF. A member is typically required to pledge approximately three-quarters of its quota as a non–interest-bearing promissory note held in its own central bank.2 The remaining one-quarter of the quota is immediately depos-ited with the IMF in a widely circulated currency or in the IMF’s own reserve asset, known as the special drawing

right. The member earns interest on almost all of that deposited amount and on any additional funds that the IMF may draw on as needed for lending. The IMF returns those additional funds to the member when the borrower repays its loan.

The SDR serves as the unit of account for the IMF. The value of the SDR is based on a basket of widely circulated currencies—currently the U.S. dollar, euro, Japanese yen, and pound sterling—that are reviewed and, if necessary, adjusted every five years.3 As of May 2, 2016, one SDR was equivalent to $1.42.4 The IMF pays its members interest at a rate, referred to as the SDR rate, that is based on the short-term interest rates charged on the debt of the countries whose currencies are in the basket; a floor of 0.05 percent was established on the SDR rate in October 2014. The interest rate that members borrowing from the IMF pay on their loans is higher than that SDR rate but indexed to it.

Voting power at the IMF is apportioned on the basis of members’ financial commitment. Each member is granted voting shares roughly proportional to the size of its quota. Voting rights are exercised through two boards established by the IMF: the Board of Governors and the Executive Board. The Board of Governors, which consists of one board member from each member country, is the main decisionmaking entity of the IMF; each board member’s vote is weighted on the basis of the member country’s voting shares. The Board of Governors dele-gates day-to-day management of the fund as well as cer-tain other powers to the Executive Board, which consists of 24 directors (appointed or elected by one of the larger countries or by groups of smaller countries) and a manag-ing director (appointed by the full Executive Board). Those directors cast the voting shares of the country or countries that they represent on the Executive Board. A few major decisions require support of members repre-senting at least 85 percent of the total voting power, so as the only member whose voting share is more than 15 percent, the United States holds certain veto powers.

2. International Monetary Fund, IMF Financial Operations, 2015 (October 2015), pp. 39–41, www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/finop/2015.

3. The Chinese renminbi will be added to the SDR’s basket of currencies on October 1, 2016.

4. The SDR value is calculated daily. Unless otherwise noted, all conversions from SDRs to U.S. dollars in this report are based on a rate of $1.42 per SDR.

JUNE 2016 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

Table 1.

Voting Shares and Quotas of IMF Members

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the International Monetary Fund.

Data were current as of February 2016.

IMF = International Monetary Fund; SDR = special drawing right.

a. The IMF uses its own international reserve asset, the SDR, as its unit of account. SDR amounts were converted to U.S. dollars at the rate of $1.42 per SDR.

b. In February 2016, 178 other countries belonged to the IMF.

Member

United States 16 118 17Japan 6 44 6China 6 43 6Germany 5 38 6France 4 29 4United Kingdom 4 29 4Italy 3 21 3India 3 19 3Russia 3 18 3Brazil 2 16 2All Other Membersb 47 302 45____ ____ ____Total 100 677 100

Voting Share (Percent) Billions of Dollarsa Percentage of TotalQuota

The IMF reviews the quotas once every five years and recommends adjustments to the system if necessary. The most recent adjustment was agreed upon by IMF mem-bers in December 2010 and implemented in January 2016 after the United States approved it. The main changes made were to increase the IMF’s ability to respond to members’ borrowing needs by doubling the total size of the quotas across all nations (to approxi-mately $677 billion) and to realign the quotas among members to more accurately reflect each nation’s contri-bution to the world economy.5 The United States, Japan, China, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom now have the largest quotas and voting shares (see Table 1).

Permanent funding pledged through quotas is not the IMF’s only source of financing. In the event that mem-bers’ borrowing needs exceed available quota resources, the IMF has arranged to obtain additional resources through two standing multicountry borrowing programs—the General Arrangements to Borrow (GAB) and the New Arrangements to Borrow (NAB)—and through

5. International Monetary Fund, “IMF Board of Governors Approves Major Quota and Governance Reforms” (press release, December 16, 2010), www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2010/pr10477.htm.

bilateral agreements with individual member countries (or their central banks). When the IMF draws on non-quota funds, the member nation providing those funds receives SDRs in exchange and earns the SDR interest rate on those holdings, just as it does on its quota funds. As of March 2016, the IMF’s nonquota resources totaled $654 billion ($258 billion in the combined GAB and NAB and $396 billion in bilateral agreements), only slightly less than the $677 billion that its quota resources are currently worth.

The United States’ commitment to the IMF currently totals approximately $164 billion, including $118 billion in quotas, $40 billion in the NAB, and $6 billion in the GAB. In recent years, lawmakers took two legislative actions that affected that commitment. First, in 2009, in response to the global financial crisis, they approved an increase of about $8 billion in the United States’ quota and a pledge of about $100 billion to the NAB. Then, in 2015, lawmakers approved the 2010 IMF quota and voting reforms, increasing the United States’ quota by approximately $60 billion but reducing its NAB obliga-tion by that same amount, leaving its total commitment to the IMF unchanged. Those changes were written into the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (Public Law 114-113), which the President signed into law in

CBO

6 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND JUNE 2016

CBO

Table 2.

The IMF’s Total Outstanding Loan Balances, by BorrowerBillions of Dollars

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the International Monetary Fund.

Data were current as of February 2016.

Amounts shown represent the outstanding portion of the lending arrangement between the IMF and the borrowing member; they do not include any undrawn balances available to the borrower under the terms of the arrangement.

The IMF uses its own international reserve asset, the SDR, as its unit of account. SDR amounts were converted to U.S. dollars at the rate of $1.42 per SDR.

IMF = International Monetary Fund; SDR = special drawing right.

a. In February 2016, 178 other countries belonged to the IMF.

December 2015. The cost to the federal government of that $60 billion quota increase was approximately $1.2 billion, or about 2 cents per dollar committed, CBO estimates. (The NAB rescission resulted in a reduction in cost of similar magnitude, but those outlays were scheduled to be made over a different period.)

The 2010 IMF reforms that took effect following the enactment of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016, had only a small effect on the United States’ posi-tion within the IMF. Although they nearly doubled the United States’ quota, they had little effect on its share of all quotas, reducing it slightly, from 17.7 percent to 17.4 percent. The country’s voting share also decreased, from 16.7 percent to 16.5 percent, but the United States retains its veto over a few major IMF decisions—such as a change in quotas or the authorization to sell gold—because it still holds more than 15 percent of the voting shares.

Lending ActivitiesThe resources committed by the United States and other member countries are available to the IMF to provide loans to its members under a variety of lending programs.

Borrowing MemberPortugal 21.0Greece 17.5Ukraine 10.9Ireland 5.4Pakistan 5.1Jordan 1.8Tunisia 1.4Iraq 1.3Cyprus 1.1Cote d'Ivoire 1.1All Other Membersa 11.7_____Total 78.4

Outstanding Balance

The amount outstanding at any point in time fluctuates with local, regional, and global economic conditions. For example, lending increased by nearly 40 percent from January 1995 to December 1995 largely because of distress in Mexico, the Russian Federation, and Argentina. It spiked again between 2001 and late 2003 primarily as a result of loans to Brazil, Turkey, and Argentina. Finally, outstanding loan balances increased by more than 800 percent from early 2007 to the end of 2011 in response to the global financial crisis. The unpaid amounts declined to less than $80 billion in February 2016 because many loans issued during the crisis had been repaid either in part or in full (see Table 2). Outstanding loans are now most prevalent among European borrowers. Almost two-thirds of those loans have been made to three countries—Portugal, Greece, and Ukraine.

The potential call on the IMF’s resources is larger than the outstanding loan balances at any particular time because most of the IMF’s borrowing programs offer member countries a line of credit that can be drawn on as needed. The undrawn portion of that credit line is not included in the outstanding loan balanaces given above. For example, in February 2016, Mexico was approved for a credit line of more than $67 billion but had not drawn on that line. In total, available but undrawn credit equaled $112 billion at the beginning of February 2016. (Only $6 billion in such undrawn credit was avail-able at the end of 2007, after the global financial crisis had begun).6

The IMF provides loans to member countries under a number of different lending programs depending on the circumstances that the member faces. In general, those programs differ on three main dimensions:

B Length of loan—IMF loans are designed to assist countries with temporary imbalances or longer-term structural difficulties. Shorter-term loans require repayment in less than five years, whereas longer-term programs have terms of up to ten years.

B Conditionality—Most loan programs require borrowing members to adopt reforms in exchange for IMF support. Those reforms are designed to alleviate conditions such as high inflation and budget deficits, to fix structural issues in the financial system and tax

6. Undrawn lines of credit at the end of 2007 totaled 3.573 billion SDRs; CBO converted that amount to U.S. dollars using the rate in effect at the time, which was $1.57 per SDR.

JUNE 2016 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

system, and to increase the likelihood of repayment to the IMF. Conditions are monitored throughout the disbursement and repayment periods to ensure adequate progress is made against quantitative and qualitative benchmarks.7

B Concessions—Some loan programs offer terms, such as initial interest rates as low as zero percent, designed to make repayment easier for borrowing members identified as low-income countries. In addition, the IMF has partnered with the World Bank and other institutions to implement programs that provide debt relief to heavily indebted countries in an effort to reduce poverty and to allow those countries to retain the resources necessary to implement social support initiatives.8

In spite of lending terms that are designed to improve borrowing countries’ economic circumstances, some IMF loans go into arrears. Such arrearages have been limited because members have generally prioritized the repay-ment of IMF loans over the repayment of debt owed to other creditors, thereby granting the IMF de facto senior creditor status.9 In addition, the IMF has developed a set of policies designed to foster collaboration with member countries to allow them to repay their arrears and protect the organization’s finances. (See Box 1. for a discussion of arrearages on IMF loans.)

The IMF’s Balance Sheet and ReservesThe IMF’s largest assets are its currency holdings—those deposited by members that it holds directly as well as amounts pledged but retained at members’ central banks for which the IMF holds promissory notes—and out-standing loans to borrowing members (see Table 3 on page 10). The balance between currencies and outstanding loans fluctuates with changes in members’ need for credit. The IMF also holds investments in a range of financial securities—deposits with international financial institu-tions, sovereign and corporate bonds, and a global portfolio

7. International Monetary Fund, “IMF Conditionality” (March 24, 2016), www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/conditio.htm.

8. International Monetary Fund, “IMF Support for Low-Income Countries” (April 1, 2016), www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/poor.htm.

9. The preferred creditor status derives from the traditional practices of debtors; it is not specified in the articles of agreement of the IMF. See General Accounring Office, Status of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Debt Relief Initiative, NSIAD-98-229 (September 30, 1998), www.gao.gov/products/NSIAD-98-229.

of common stocks, for example. In addition, the organi-zation holds gold in reserve: In the early years of the IMF, members paid part of their initial quotas in gold, and later trans-actions with member countries added to those holdings. The IMF’s largest liabilities are the quotas of member countries, which it must repay, and the amounts owed to members that have lent money to the organiza-tion under the NAB, the GAB, or separate agreements with the IMF.

At the end of October 2015, the IMF reported that its assets exceeded its liabilities by nearly $26 billion. The IMF records that excess amount as reserves, but it effec-tively represents the organization’s net worth. The reported amount is based on the value of the IMF’s nearly 3,000 metric tons of gold being recorded at historical cost—that is, at the value of the gold when it was acquired. If those gold holdings were instead recorded at the market price on October 31, 2015, the value of the IMF’s reserves would increase by nearly $100 billion, increasing the difference between assets and liabilities to about $126 billion (see Figure 2 on page 11).

The IMF’s total reserves have grown since 2008. Based on the market price of gold, the value of all reserves increased by nearly 80 percent from 2008 to 2015. In large part, that growth resulted from an increase in the market price of gold, which rose from $724 per ounce in October 2008 to $1,721 per ounce in October 2012 before falling to $1,142 per ounce in October 2015. In addition, in 2010 the IMF began to build up its reserves in response to increases in current and projected lending. Excluding its gold holdings, the IMF’s reserves grew from less than $1 billion in 2008 to slightly less than $21 billion in 2015.

The IMF can use its reserves to mitigate any losses that it might incur on its outstanding loans before those losses are imposed on members.10 For example, if the IMF wrote off a loan to a member country in arrears, the IMF could use reserves to cover the shortfall, thereby main-taining the quota balances of the members whose funds

10. The ability of the IMF to sell gold to offset losses is restricted. Such sales can be vetoed by the United States or any combination of other countries whose collective vote totals 15 percent of all voting power. See International Monetary Fund, “Gold in the IMF” (April 13, 2016), www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/gold.htm; and Government Accountability Office, IMF: Planning for Use of Gold Sales Profits Under Way, but No Decision Made for Using a Portion of the Profits, GAO-12-7666R (July 26, 2012), www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-766R.

CBO

8 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND JUNE 2016

CBO

Continued

Box 1.

The International Monetary Fund’s Loans in Arrears

Although the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has never incurred a loss severe enough that the loss was passed on to its members, some of its loans have gone into arrears—that is, the borrowers have failed to make obligated scheduled payments on those loans (see the figure). Total arrearages have never exceeded $6 billion; however, arrearages as a percentage of out-standing loan balances have exceeded 10 percent during two different periods since 1984—from 1988 to 1994, when arrearages peaked at 15 percent of outstanding balances in 1990, and from 2006 to 2007, when they reached 19 percent as the IMF’s total outstanding loan balances dropped significantly during the global economic boom that preceded the worldwide recession that started in 2007. Some countries have been in arrears for 10 years or more.

Not all countries that ultimately clear their arrearages do so by resuming normal payments of principal and interest to the IMF. Liberia, for example, resolved its 23-year delinquency to the IMF by taking a loan from the United States that it used to repay its IMF loan. It then borrowed new funds from the IMF to repay the loan from the United States. The IMF granted Liberia debt relief in 2010, so it never repaid those new IMF loans in full.1 Because of the relatively small amount of money involved, forgiving those loans had a very small impact on the IMF’s overall financial position, but the example illustrates one channel through

which the IMF’s lending activities have led it to record a net reduction in its net worth.2

In addition to offering its own debt-relief programs, the IMF has benefited from the assistance provided by other nations to help borrowing members clear their arrearages on IMF loans. Perhaps most notable is the case of Greece, which missed two payments to the IMF on June 30 and July 13, 2015. After receiv-ing more than 7 billion euros in assistance from the European Union (EU), Greece settled its overdue payments with the IMF on July 20, 2015.3 To avoid losses, the IMF has thus depended on successfully coordinating arrangements between its debtors and other creditors. As of February 2016, Greece still owed the IMF $17.5 billion; its ability to repay those loans will most likely depend on additional support from the EU.

1. International Monetary Fund, IMF Financial Operations, 2015 (October 2015), p. 73, www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/finop/2015.

2. Generally, debt-relief activities are funded separately from the IMF’s regular lending operations using resources from the IMF’s prior gold sales as well as nonquota commitments made by member countries.

3. Council of the European Union, “EFSM: Council Approves €7bn Bridge Loan to Greece” (press release, July 17, 2015), http://tinyurl.com/jb3gbgn.

provided the loan. (Although borrowers, such as Greece in 2015, have missed required payments on loans and the IMF has forgiven some loans to poorer nations, the organization has never deemed one of its loans to be unrecoverable.)

The Effects of Large LossesIf the losses that the IMF incurred on its loans were large enough, it would eventually pass some losses on to its members. The timing and form of the losses that mem-bers would incur depend on the actions that the IMF took in response to a crisis. The IMF could, for example, liquidate its investments and gold reserves as needed to

pay interest owed on members’ SDR holdings. If the losses were large enough, those balances would eventually be exhausted, and the IMF would then have no choice but to lower the interest that it paid to members. Alterna-tively, the IMF could retain its investments and gold resources and immediately limit the interest payments that it made to its members to the proceeds available. Although the amount of interest received by members in those two cases would be different, in either case mem-bers would incur similar losses, which in present-value terms would roughly equal the amount of the losses on the IMF loans minus the value of the organization’s reserves.

JUNE 2016 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

Box 1. Continued

The International Monetary Fund’s Loans in Arrears

Overdue IMF Loans, 1984 to 2012

Billions of Dollars Percent

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the International Monetary Fund.

The IMF uses its own international reserve asset, the SDR, as its unit of account. SDR amounts for each year were converted to U.S. dollars using the exchange rate that was in effect at the end of that calendar year.

IMF = International Monetary Fund; SDR = special drawing right.

The frequency of arrearages on IMF loans is lower than the frequency of default on loans provided by other sovereign creditors because the IMF’s position in the international finance community often allows it to negotiate the most favorable repayment terms. Before providing emergency financial assistance to Greece, for example, the IMF, with the backing of the EU, required other holders of Greek debt to first take

losses and write down their debts. If Greece cannot pay all of its remaining debts in the future, those creditors will have a lower payment priority than the IMF. The experience with Greece highlights how the terms that the IMF negotiates, including its repay-ment priority, make its loans more secure than other sovereign debt.

1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 20120

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

5

10

15

20

Overdue Balances as aPercentage of the IMF's

Total OutstandingLoan Balances

(Right axis)

Number ofMonths Overdue

6 or More

1 to 6

0 to 1

Other alternatives would probably require Congressional approval before the IMF could implement them, but it is unlikely that those actions would lower the cost to mem-bers of resolving a loss. Members could, for example, choose to recapitalize the IMF either by providing it with funds to allow the write-down of loans in arrears or by providing funds to the borrowing members to repay those loans. The United States most likely could not participate in a recapitalization of the IMF without authorization by the Congress. The United States could abstain from par-ticipating in such a recapitalization, but the possibility of a recapitalization occurring without the United States’ involvement is, in CBO’s judgment, remote.

Another option would be for the IMF to liquidate its assets and pay the proceeds to members that still held SDRs.11 The amounts that the IMF would receive from selling its portfolio of loans (those in arrears as well as those in good standing) and other assets would be less than its liabilities—the largest being the quotas of its members—so each member’s share of the proceeds would

11. The IMF’s articles of agreement describe the approval process for a liquidation (Article 27, Section 2) and settlement of liabilities from funds acquired as a part of that liquidation (Schedule K). See International Monetary Fund, Articles of Agreement of the International Monetary Fund (April 2016), www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/aa.

CBO

10 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND JUNE 2016

CBO

Table 3.

The IMF’s Balance SheetBillions of Dollars

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the consolidated financial statements of the General Department of the International Monetary Fund.

Data were current as of October 31, 2015.

Amounts shown include holdings in the IMF’s general resources account, investment account, and special disbursement account.

The IMF uses its own international reserve asset, the SDR, as its unit of account. SDR amounts were converted to U.S. dollars at the rate of $1.42 per SDR.

IMF = International Monetary Fund; SDR = special drawing right.

a. The IMF holds 2,814 metric tons of gold in reserve. The value shown is based on the historical cost of those reserves; the market value of those holdings was an estimated $105 billion as of October 31, 2015.

be less than the value of its quota. Like recapitalization, liquidation would require Congressional action before the United States could vote to approve such a decision.

Budgetary Treatment of the United States’ Participation in the IMFThe budgetary treatment of the United States’ participa-tion in the IMF has changed several times since 1945. Because the United States’ commitments to the IMF are sufficiently different from other spending programs in the federal budget, they are not easily assessed using the

Category

AssetsCurrencies 296.8 Outstanding loan balances 73.3 ______

Total currencies and outstanding balances 370.1

Investments 21.2 SDR holdings 20.3 Gold holdingsa 4.5 Property, plant, and equipment 0.6 Interest and charges receivable 0.5 Other assets 0.6 ______

Total assets 417.7

LiabilitiesQuotas 338.2 Borrowings 50.0 Special contingent account 1.7 Employee benefits 1.3 Other liabilities 1.1 ______

Total liabilities 392.3

Reserves (Total assets minus total liabilities) 25.5

Amount

accounting methods applied to those other programs. The current treatment, first used in 2009, records the nation’s commitments to the IMF in the budget on a fair-value basis—that is, on a present-value basis with an adjustment to account for market risk. Before 2009, commitments were treated either as having no impact on the budget or as creating budget authority equal to the full value of the commitment. (Budget authority is the authority provided by law to incur financial obligations that will result in immediate or future federal outlays.) Each treatment has advantages and disadvantages in pro-viding a useful measure of the cost of the United States’ participation in the IMF.

CBO’s Current Budgetary Treatment of Commitments Made to the IMF and the Effect of Recent LegislationThe use of the fair value method to estimate the cost of the United States’ commitment to the IMF was first mandated in the Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2009 (P.L. 111-32), which provided an increase of about $8 billion in the United States’ quota and a pledge of about $100 billion to the NAB. That approach was reaf-firmed in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016, the last time legislation affecting U.S. funding for the IMF was enacted. CBO has concluded that it would con-tinue to use that approach in analyzing future legislation that provided U.S. funding for the IMF, even if the pro-posed legislation specified a different methodology. CBO would modify its approach if a change to the budgetary treatment of IMF funding was enacted into law, if the Congress specified a different treatment in a budget reso-lution, or if the Congress and the Administration jointly agreed to a different treatment.12

Under that approach, the cost of any new commitment is estimated by projecting how it would change the net cash flows between the United States and the IMF over time and then using a discount rate to convert those cash flows to an equivalent single lump sum today—a present value. Because the agency uses a market-based discount rate that

12. On a few occasions in recent years, CBO provided cost estimates for bills using a different treatment—a present-value approach that did not include an adjustment to account for market risk. CBO has now concluded that it would use the fair-value approach in analyzing future legislation that provided U.S. funding for the IMF. See, for example, Congressional Budget Office, cost estimate for S. 2124, the Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Ukraine Act of 2014 (March 24, 2014), www.cbo.gov/publication/45204.

JUNE 2016 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

Figure 2.

The IMF’s Reserves, 2000 to 2015Billions of Dollars Percent

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the consolidated financial statements of the General Department of the International Monetary Fund.

Reserves are measured as the difference between total assets and total liabilities.

The IMF uses its own international reserve asset, the SDR, as its unit of account. SDR amounts for each year were converted to U.S. dollars using the exchange rate that was in effect at the end of October of that year.

The value shown for the IMF’s reserves with gold holdings at market price for each year reflects the market price of gold on October 31 of that year.

IMF = International Monetary Fund; SDR = special drawing right; * = less than $1 billion.

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 20150

50

100

150

200

250

0

200

400

600

800

With Gold atMarket Price

(Left axis)

Reserves, With Gold atMarket Price, as a

Percentage of OutstandingLoan Balances

(Right axis)

With Gold atHistoric Cost

(Left axis)

ExcludingGold

(Left axis)

* * ** *

reflects the time value of money and the cost of the mar-ket risk associated with the United States’ commitment to the IMF, the resulting fair-value estimate approximates the price that the federal government would need to pay a market participant to provide the same commitment to the IMF under identical terms.13

The present-value estimate is based on a probabilistic assessment of the range of outcomes for loans made by the IMF to member countries, which is described below. Historical experience suggests that, in most scenarios, the IMF would suffer no losses and would collect interest and the full principal amount of a given loan by the end of its term. However, CBO estimates that in some scenarios, the IMF would collect less than the full principal amount disbursed to the borrowing country. Some of those cases could involve losses so large that they would exceed the

13. Loans, including loans to large multinational organizations such as the IMF, have market risk because borrowers tend to default more frequently when the global economy is weak, and thus their risk cannot be eliminated through diversification. For further discussion, see Congressional Budget Office, Fair-Value Accounting for Federal Credit Programs (March 2012), www.cbo.gov/publication/43027.

IMF’s reserves and would lead to losses to members. In CBO’s judgment, losses would be largest when which the global economy is weakest and the market price of risk is elevated. Thus, the inclusion of an adjustment for market risk results in costs that are significantly greater than the probability-weighted average of all possible loss outcomes discounted at the rates appropriate for safe, nominal cash flows.

The current budgetary treatment applies only to commit-ments that the United States has made to the IMF since 2009. To estimate the budgetary effects of just those amounts in its baseline budget projections, CBO first constructs two projections of the IMF’s finances: one with the United States’ commitments made after 2009 and one without them. For each of those projections, the agency simulates the inflows and outflows to the IMF from investments, loans, quotas, lines of credit, and oper-ating expenses to estimate the organization’s assets and liabilities under a range of outcomes for loans made by the IMF to member countries (see Figure 3). CBO then calculates the difference in the cash flows of those two projections to estimate the cost of the new commitments.

CBO

12 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND JUNE 2016

CBO

Figure 3.

Cash Flows Between the United States and the IMF

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

IMF = International Monetary Fund.

InternationalMonetary FundUnited States

BorrowingMembers

Contributions

Repayment of Contributions

Loans

Repayment of Loans, Minus Defaults

Investments OperatingExpenses

Interest Payments onContributions

Interest Payments onLoans

Annual cash flows are averaged across all scenarios and expressed as a present value using a discount rate that includes the cost of market risk inherent in IMF lending.

When analyzing proposed legislation that would change the United States’ commitment to the IMF, CBO also uses such a present-value approach to calculate projected budget authority and outlays. Because the IMF would not draw on all of the new resources immediately, the outlays stemming from that budget authority are projected to occur over many years.

CBO’s method of accounting for the budgetary effects of the United States’ participation in the IMF is illustrated by its estimate of the changes authorized in the Consoli-dated Appropriations Act, 2016. As a part of that act, the Congress approved the IMF’s recommendation to shift funding from the NAB to quota commitments, providing roughly $60 billion for an increase in the United States’ quota commitments to the IMF and rescinding an equiva-lent amount of support for the NAB. For both the $60 bil-lion increase in the United States’ quota and the $60 bil-lion NAB rescission, CBO’s baseline shows a change in budget authority of about $1.2 billion, or 2 percent per dollar committed. Hence, the legislation resulted in no net change in budget authority. CBO estimates that the legislation will have the net effect of increasing outlays by $236 million in 2016 because of differences in CBO’s

estimates of when the budget authority for quota and NAB commitments result in outlays.14

The Administration also estimates the cost of the United States’ commitments to the IMF made after 2009 on a present-value basis, but its estimates differ from CBO’s in both size of the costs and the timing of when they are reflected in the budget. Whereas CBO’s estimate is driven by expected losses and the market risk associated with those losses, the Administration’s estimate does not reflect the cost of any estimated losses. Those differences can be seen in the respective estimates of the budgetary effect of the 2016 quota increase. In its proposed budget for fiscal year 2017, the Administration attributed budget author-ity of $0.145 billion to the roughly $60 billion quota

14. For changes in the United States’ quota, CBO projects that 25 percent of the budget authority results in outlays in the year that the legislation authorizing a change becomes effective. In each of the next 15 years (year 2 through year 16 after the legislation becomes effective), 5 percent of the remaining budget authority is projected to result in outlays. For changes in the United States’ NAB or GAB commitments, CBO projects that 5 percent of budget authority results in outlays in each of the 20 years following enactment. Although the timing of when budget authority results in outlays is different for changes in the quota and changes in NAB or GAB commitments, CBO uses the same cost of 2 cents per dollar, which is based on expectations about the timing of when the IMF will use the United States’ commitments (of any form) to support its lending.

JUNE 2016 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

Table 4.

Budgetary Treatment of the United States’ IMF Quota CommitmentsBillions of Dollars

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the International Monetary Fund.

The IMF uses its own international reserve asset, the SDR, as its unit of account. SDR amounts were converted to U.S. dollars using the exchange rate that was current at the time the commitment was made. Exchange rate data were not available for some years. For commitments made before 1972, an exchange rate of $1.00 per SDR was used; for those made between 1978 and 1983, a rate of $1.10 per SDR was used.

IMF = International Monetary Fund; SDR = special drawing right.

a. The budgetary treatment was specified in the Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2009 (Public Law 111-32), which authorized the additional commitment.

Date of Commitment Budgetary Treatment

Before 1980 Not recorded in the budget 91980 to 1999 Recorded as an increase in budget authority with no effect on outlays 372011 Recorded under Federal Credit Reform Act rules with an adjustment for market riska 82016 Recorded at fair value (present value with an adjustment for market risk) 60______

Total Commitment 114

Amount of Commitment

increase—reflecting a cost of about 0.25 cents per dollar committed to the IMF instead of CBO’s estimated 2 cents per dollar. In addition, CBO allocated the budget outlays for the authorized amounts over several years whereas the Administration recorded the full amount of the budget authority as an outlay in the fiscal year in which the funds were committed.

Past Budgetary Treatment of Commitments Made to the IMFAlthough more than half of the United States’ total quota ($68 billion of about $114 billion) results from commit-ments that have been made to the IMF since 2009 and is thus accounted for using the current treatment, portions of the total quota arising from commitments made before 2009 are treated differently in CBO’s baseline budget projections (see Table 4).15

Before 1980, the United States’ commitments to the IMF generally did not appear in the federal budget on the grounds that transactions with the IMF were strictly an exchange of assets of equal value: The United States pro-vided dollars and in return received a liquid claim on the IMF in the form of SDRs.16 Beginning in 1980, the Congress and the Administration agreed to a new treat-ment that remained in place until 2009. The commit-ments to increase the quota that were made in that period

15. The same issue exists for GAB and NAB commitments. Those commitments were not included here because of their small size, relative to the United States’ quota, before 2009.

(all of which were made between 1980 and 1999) were counted in the budget as increases in budget authority equal to the full amounts provided, but no corresponding outlays were recorded for those transactions.

When a new commitment to the IMF was authorized in 2009, lawmakers, in consultation with CBO and the Office of Management and Budget, directed the agencies to estimate the budgetary effect on a present-value basis, in accordance with the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA). The agencies were also required to include an adjustment for market risk in the discount rate that they used to calculate the present value.17 The Consoli-dated Appropriations Act, 2016, specified the same risk-adjusted present-value approach without referencing FCRA. Dropping the reference to FCRA simplified the budgetary record keeping for the Administration.

16. Congressional Budget Office, International Balance of Payments Financing and the Budget Process (August 1977), www.cbo.gov/publication/20626.

17. The treatment of federal loans and loan guarantees is spelled out in FCRA, which requires that loans and loan guarantees made by federal agencies be evaluated by estimating all future cash flows for those loans and discounting the projected stream of such cash flows back to the time of loan approval. However, FCRA does not automatically apply to the United States’ assistance to the IMF because that assistance takes the form of a membership subscription with an exchange of financial assets and a line of credit, neither of which meets the simple definition of a loan that includes a contract that requires the repayment of such funds.

CBO

14 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND JUNE 2016

CBO

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Current and Past Budgetary TreatmentsThe changing budgetary treatment of commitments to the IMF results from the fact that each treatment has advantages and disadvantages in providing a transparent and comprehensive picture of the United States’ exposure to risks through its participation in the IMF. The approach that was used before 1980 recognizes that IMF commit-ments, like deposits in a traditional bank, are made in exchange for a claim against the IMF’s assets and could be withdrawn at some point in the future. One drawback of that method is that it effectively treats deposits with the IMF as if they were equivalent in risk to investing funds in short-term securities of the countries whose currencies make up the SDR basket when they are not.

The change made in 1980 to recognize an equal increase in budget authority (while continuing to show no out-lays) for any increase in the United States’ commitment to the IMF was an acknowledgment that such commit-ments obligate the United States to provide funds to the IMF up to the specified amount. Including the full com-mitment in the budget made decisions about the United States’ commitment to the IMF a part of the Congressional budget process and fostered additional oversight of the organization’s activities by lawmakers.

In moving to a present-value approach in 2009, lawmakers recognized that, for legislation affecting financial transac-tions, recording the total financial commitment as budget authority may be less useful than recording the generally much smaller projected net cost. Recording only the pro-jected net cost as budget authority (as is done for federal loans and loan guarantees) allows lawmakers to better distinguish the likely amount of spending that they are authorizing when comparing financial transactions with identical commitment sizes but different terms and risks. Such estimates, however, are very uncertain. The lack of an observed history of default on IMF loans poses a significant challenge to estimating, with any degree of certainty, the risk involved although that absence itself suggests that the risk is small.

The rationale for including the cost of market risk in esti-mating the costs of the government’s financial transactions is that doing so results in a more comprehensive measure of cost, one that reflects how the public values the risks taken on by the government.18 The cost of the market risk associated with any particular program can be esti-mated using the prices of securities with comparable risks.

The fair-value approach has several benefits that neither the previous approaches to accounting for new commit-ments to the IMF nor a present-value approach that excludes a market risk adjustment have. First, fair-value estimates can be intuitively interpreted as either the price that would be determined by participants in a competi-tive market for taking on the government’s obligations or as a measure of the economic subsidy that is being pro-vided to the beneficiaries of the program. Second, fair-value estimates can help policymakers understand trade-offs between policies that involve differing degrees of market risk. For example, if commitments to the IMF were being weighed against bilateral loans to other nations that did not include the benefits of the seniority and the conditionality of IMF lending, those bilateral loans would have considerably more market risk. The United States would need to charge a higher interest rate on those bilateral loans than the rate it receives from the IMF to offset that additional market risk. Finally, aligning budgetary costs with the market values makes financial transactions conducted at market prices budget neutral and thereby eliminates the incentive to conduct such transactions solely to achieve budgetary savings.

Some observers have argued that the current fair-value treatment and previous treatments ignore the gains and losses on SDRs that may result from differences in earnings from holding debt denominated in foreign currencies ver-sus debt denominated in U.S. dollars. Those differences, which can come from variations in exchange rates, interest rates, or both, would affect projections of the cost of the IMF if the IMF were accounted for on a cash basis like other federal programs. For example, if CBO projected that the exchange value of the U.S. dollar would appreci-ate against the SDR then quotas held in SDRs would (if interest rates were held constant) be projected to be less valuable in terms of U.S. dollars in the future. However, a projected increase in the SDR interest rate in relation to U.S. rates could offset part or all of that loss in value.

Although such a relationship between exchange rates and interest rates is generally assumed to hold over the long term in many economic models (an assumption known as uncovered interest rate parity), projected movements in

18. Testimony of Douglas W. Elmendorf, Director, Congressional Budget Office, before the Committee on Financial Services, U.S. House of Representatives, Estimates of the Cost of the Credit Programs of the Export-Import Bank (June 25, 2014), www.cbo.gov/publication/45468.

JUNE 2016 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

exchange rates and interest rates do not necessarily offset each other over a decade. Nevertheless, current exchange rates and interest rates are generally interpreted as reflect-ing expectations and risk tolerances of participants in the financial market. Thus, one rationale for excluding those effects from budget estimates is that the SDR interest rate and exchange rate are based on market-determined rates that effectively compensate the holder of SDRs for the exchange and interest rate risks that they bear. CBO accounts for market participants’ demand to be compen-sated for that risk by discounting SDR cash flows in present-value estimates using the weighted average of yields on debt of the countries whose currencies are in the SDR basket and then converting the SDR amount to U.S. dollars at the prevailing exchange rate. CBO does not, therefore, make any further adjustment to its pres-ent-value estimates to account for its projections of exchange rates or interest rates.

Other observers argue that the basis for assessing the size and probability of any loss associated with defaults by IMF borrowers is subjective, as is the size of an appropriate mar-ket risk adjustment, and that the estimates are therefore particularly uncertain. One approach that could mitigate that uncertainty is to exclude the market risk adjustment for losses, or the possibility of losses altogether, from the estimate. Without the market risk adjustment for losses, CBO’s estimate of the cost of additional commitments to the IMF would be 0.5 percent of the commitment instead of 2 percent. If the possibility of loss was excluded alto-gether, any estimate would simply be based on the differ-ence between the rate paid by the IMF on the SDRs and the safe, nominal rates used to convert those payments to a present value. To the extent that those rates are approxi-mately the same, the estimate would be close to zero, matching the exchange-of-assets approach. If such an approach was adopted, lawmakers would no longer receive signals as part of the budget process about changes in the risks of the United States’ commitments to the IMF as market conditions and lending policies changed. Some analysts, however, contend that lawmakers already receive sufficient information about the IMF’s lending through the Treasury’s reports to the Congress and other sources, or that, given the estimating uncertainties, fair-value estimates should be used only as supplemental information.

Other concerns about a fair-value approach are not spe-cific to transactions with the IMF; rather, they are the general concerns expressed by analysts who oppose the

use of fair-value accounting for federal credit programs in the budget.19 First, fair-value estimates include costs that will not be paid directly by the federal government if actual cash flows turn out to match expected cash flows, which makes comparing such estimates with estimated costs for programs that have market risk but whose costs are not accounted for with a market risk adjustment more difficult. Second, fair-value estimates may be somewhat more volatile, more difficult to produce, and more diffi-cult to communicate to policymakers and the public than estimates without market risk because of changes in the cost of market risk. Third, producing fair-value estimates is typically more complex than producing estimates with-out an adjustment for market risk, so it is often more dif-ficult to explain to policymakers and the public the basis for such estimates than it is to explain the basis of esti-mates that do not include adjustments for market risk.

How CBO Estimates the Fair-Value Cost of the United States’ Participation in the IMFCBO estimates that increases in the United States’ finan-cial commitment to the IMF have a cost on a fair-value basis because the rate of interest that the United States earns on the funds deposited with the IMF does not fully compensate it for the small risk of a sharp decline in the value of its commitment. When the United States makes a deposit with the IMF, it receives a rate of interest on its SDRs that is equivalent to or slightly higher than the rate it could earn investing directly in the low-risk debt of the countries whose currencies make up the SDR basket.20 Deposits with the IMF pose an additional risk, however, because some of their value may be lost as the result of a large-scale loss stemming from widespread defaults on IMF loans.

Under the fair-value approach to estimating costs, the benchmark for determining the net cost of a particular investment is the return that would be earned on an invest-ment with comparable risk; if the cash flows from the investment fall short of that benchmark, the investment

19. See Government Accountability Office, Credit Reform: Current Method to Estimate Credit Subsidy Costs Is More Appropriate for Budget Estimates Than a Fair Value Approach GAO-16-41 (January 2016), www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-41.

20. The 0.05 percent floor on the SDR rate provides a slightly better return than investing in the debt of the countries whose currencies are included in the basket when yields on those countries’ debts are negative, as some have been since 2014.

CBO

16 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND JUNE 2016

CBO

Table 5.

CBO’s Fair-Value Estimate of the Cost to the United States of New Commitments to the IMF

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

IMF = International Monetary Fund.

a. Amounts shown represent the net present value of cash flows associated with new loans disbursed by the IMF as a result of a new commitment, expressed as a percentage of that commitment.

b. CBO estimates that each dollar of a new commitment to the IMF would result in a sequence of loan disbursements that, on a present-value basis, exceeds the amount of the commitment.

Loan Disbursementsb 138.9Scheduled Loan Repayments -141.3Loan Losses 5.3____

Cost to the IMF of Its Loans 3.0

Income Retained by the IMF as Reserves 2.4Losses Absorbed by the IMF's Reserves -3.4____

Combined Effect of the IMF's Reserves -0.9

Cost to the United States of New Commitments to the IMF 2.0

Cash Flow (Percent)a

has a net cost. Investments with more market risk gener-ally provide a higher expected rate of return than those with less market risk to compensate investors for bearing the additional risk. The United States’ commitment to the IMF has slightly more market risk (stemming from the possibility of losses triggered by widespread defaults) than investing directly in the low-risk debt of the coun-tries whose currencies are included in the SDR basket, so market participants would demand a slightly higher inter-est rate than the SDR rate to compensate them for that risk. If the IMF paid a higher rate than it currently pays on SDRs, that would reduce the cost of the United States’ par-ticipation in the IMF. Conversely, if the IMF paid mem-bers a lower rate, that would increase the cost to members.

To quantify the cost of an increase or decrease in the amount of the United States’ commitment to the IMF, CBO models the cash flows between the United States, the IMF, and its borrowers. Because the sequence of events that would generate losses for the United States’ commitment to the IMF has no clear historical precedent, those cash flows are highly uncertain.

The modeling approach involves a series of steps, each of which produces a set of cash flows that represents the effect of a change in the United States’ commitment on the amount that the IMF lends out in each year.21 The components of the IMF’s cash flows can be grouped into two categories: the costs of lending and reductions in the

costs that the organization passes on to members resulting from its reserves. CBO estimates the amounts of the loans that the IMF would disburse to borrowers as a result of the new commitment, the scheduled repayments of principal and interest on those loans, and the present value of any losses that the IMF would incur if borrowers defaulted. The IMF uses its reserves to reduce the amount of losses that are borne by members. To build those reserves over time and to cover its operating costs, however, the IMF retains a portion of the proceeds from its lending, which reduces the interest payments that it makes to the United States.

Each of those sets of cash flows can be expressed as a present value; added together, those present values consti-tute the estimated net cost of United States’ participation in the IMF (see Table 5). Combining the present value of the IMF’s loan disbursements, scheduled repayments, and losses yields a net cost to the IMF of 3 percent of its

21. Quota deposits that are not lent by the IMF are invested in a range of securities purchased at market prices or held as currency. On a fair-value basis, those investments will provide cash flows that fully offset their purchase prices, and they therefore have no effect on the fair-value cost of the United States’ commitment to the IMF. The remaining portion of the quota commitment that is not deposited with the IMF is retained at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in the form of a non–interest-bearing promissory note until it is drawn on by the IMF, so it does not affect the net cost of the commitment either.

JUNE 2016 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

loans. The net cost indicates that the IMF provides loans on terms that are more generous than those that would be demanded by other creditors if they were granted the same seniority and made loans under the same conditions as the IMF. The cost that is passed on to the United States is increased by a small amount because the IMF retains some of the interest it receives, but the cost is low-ered by a much greater amount by the organization’s reserves, which insulate the United States from most losses. Together those effects reduce the net cost to the United States of an increase in its commitment to the IMF to 2 percent of the additional commitment—lower than the costs that the IMF itself bears on its loans.

Loan DisbursementsCBO projects that for any given increase in the United States’ commitment, the IMF would, on average, have about 10 percent of that increase loaned out to members in any given year, though that amount will vary from year to year with changes in global economic conditions. That projected share is slightly higher than the 8 percent share of total resources on loan that the IMF has maintained since expanding its lending resources in 2009 in response to the global financial crisis but lower than the 16 percent share maintained between 2000 and 2008. CBO esti-mates that IMF loans will mature after about two years, so with nonamortizing loans (that is, loans for which the principal is due at the maturity date) that projected share amounts to disbursements equaling 5 percent of the new commitment each year, in perpetuity. The present value of that sequence of future disbursements is 139 percent of the commitment.

Scheduled Loan RepaymentsThe IMF would receive interest on outstanding balances of its loans to borrowing members that stemmed from the new commitment at a rate approximately equal to the projected SDR rate plus a nearly 1 percentage-point spread, CBO estimates. That estimate is roughly consis-tent with the rates that the IMF has charged on its loans over the past 20 years. The expected stream of principal repayments (5 percent of the IMF’s total resources each year) and interest payments (on the 10 percent of total resources that the IMF is projected to have in outstanding loan balances each year) has a present value of 141 per-cent of the new commitment.22 The difference between that amount and the present value of loan disbursements is the value of the income that the IMF would earn by charging its borrowers an interest rate higher than the rate it pays to members on their SDR holdings.

Loan LossesThe projection of losses on the loans made by the IMF to member countries is the most uncertain component of CBO’s estimate of the cost of commitments to the IMF. It is based on estimates of several key parameters—the frequency of large losses, the severity of losses, and the amount of IMF loans extended when such losses occur—all of which are very uncertain and subjective. That uncer-tainty stems in large part from the lack of any history of significant losses incurred by the IMF. That history sug-gests that, in most scenarios, the IMF would be protected from substantial losses by the seniority of its claim, the conditionality of its lending, and the actions of other nations intended to ensure that borrowers repay their IMF loans.23 Thus, CBO’s estimate focuses on losses that would occur in severe crises when global levels of public and private indebtedness are high and the factors that make the IMF’s lending safer than other sovereign debt are more likely to be tested.

In CBO’s judgment, events similar to the Great Depression or the recent financial crisis are most likely to cause the IMF to incur significant losses. Approximately 75 years separated those two events, which CBO considers to be a reasonable estimate of the frequency of severe crises. However, the IMF did not incur losses on the loans it made in the last financial crisis, suggesting that not all such events lead to losses. Thus, CBO estimates that the IMF would incur a large loss in only one out of every four such events. Combining those probabilities, CBO estimates that the annual probability of a crisis occurring that triggered large IMF losses is 1 in 300.

During such a crisis, CBO estimates, an average of 30 cents of each dollar of any new commitment that the United States made to the IMF would end up in arrears. That estimate reflects two expectations about such a crisis—that IMF lending would increase and so, too, would the

22. The estimates of interest rates that would be paid by members on their loans include the effects of the 0.05 percent floor on the SDR rate, which raises the value of the scheduled loan repayments by approximately 0.20 percent of the commitment.

23. In addition to the specific elements of the IMF’s lending practices, the coordinated interventions of the United States and the European Union to address the recent global crisis helped the IMF avoid losses. The liquidity swap lines established by the Federal Reserve System, the United Kingdom’s Exchange Equalisation Account, and eurozone members’ European Stability Mechanism are examples of such coordinated efforts.

CBO

18 THE BUDGETARY EFFECTS OF THE UNITED STATES’ PARTICIPATION IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND JUNE 2016

CBO

Figure 4.

The IMF’s Total Outstanding Loan Balances, 1984 to 2015Billions of Dollars

Source: Congressional Budget Office, using data from the International Monetary Fund.

Amounts shown represent the outstanding portion of the lending arrangements between the IMF and borrowing members at the end of each year; they do not include any undrawn balances available to borrowers under the terms of those arrangements.

The IMF uses its own international reserve asset, the SDR, as its unit of account. SDR amounts for each year were converted to U.S. dollars using the exchange rate that was in effect at the end of that calendar year.

IMF = International Monetary Fund; SDR = special drawing right.

24

1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 20140

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

probability that borrowers would go into arrears. CBO anticipates that the amount of lending and the number of lines of credit extended during a crisis would be much greater than the average of 10 percent of the United States’ commitment projected by CBO. Historically, the IMF’s lending has grown significantly during inter-national economic crises. For example, lending increased during the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, the Asian financial crisis of the 1990s, and the global finan-cial crisis of the late 2000s (see Figure 4). In addition, during that global financial crisis, the IMF extended lines of credit that remained undrawn but nevertheless allowed for an even greater increase in outstanding loan balances. When the IMF’s lending in response to the global finan-cial crisis peaked in 2012, outstanding balances and