Complications of Bariatric Surgery: What You Can Expect to ... · Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB)...

Transcript of Complications of Bariatric Surgery: What You Can Expect to ... · Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB)...

RE

VIE

W1640

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 112 | NOVEMBER 2017 www.nature.com/ajg

CLINICAL AND SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

INTRODUCTION

Th e increasing prevalence of obesity and its associated co-mor-

bidities has resulted in a substantial increase in the number of

bariatric procedures performed worldwide ( 1–5 ). In fact, bariatric

surgery has become one of the fastest growing operative proce-

dures and has gained acceptance as the leading option for sus-

tained weight-loss in the treatment of morbid obesity ( 3 ). As this

fi eld continues to expand, gastroenterologists will see an increas-

ing number of patients with surgically altered anatomy. Th ere

are a number of unique complications that arise in this patient

population that require specifi c knowledge for proper manage-

ment. Furthermore, conditions unrelated to the altered anatomy

typically necessitate a diff erent management strategy. As such, a

basic understanding of surgical anatomy, potential complications,

and endoscopic tools and techniques for optimal management is

essential for the practicing gastroenterologist. It is important to

co-manage these conditions with a surgical team, as endoscopic

approaches may not always be successful, and surgical reinterven-

tion may not always be suffi cient. For all of the endoscopic pro-

cedures discussed, it is critical to use carbon dioxide insuffl ation

to minimize complications and post-procedural pain. Further-

more, there should be a low threshold for anesthesia consultation,

as bariatric patients may have complicated airways, obstructive

sleep apnea, require more medication, or may be at other risk of

conscious sedation. Th is review will cover these topics and focus

on major complications that gastroenterologists will be most

likely to see in their practice.

ROUX-EN-Y GASTRIC BYPASS

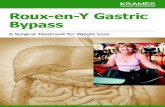

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) has traditionally been the

most common bariatric procedure, accounting for almost half of

all bariatric surgeries performed worldwide ( 3 ). Th is procedure

involves stapling the stomach to create a small gastric pouch,

along with diversion of oral intake and biliopancreatic digestive

enzymes to the distal small bowel, via creation of a Roux limb

( Figure 1a ).

Various hormonal mechanisms are implicated depending on

surgical technique employed ( 6–8 ). Foregut theories suggest the

role of a hormone that is released from the duodenum and contrib-

utes to insulin resistance. Th is substance is no longer thought to be

secreted following gastric bypass surgery in the foregut hypothesis.

In addition, gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP), which is secreted

from the duodenum, is thought to have a role. In hindgut theory,

bile and undigested food are thought to stimulate L-cells to pro-

duce glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and Peptide YY (PYY) as

well as other substances which cross the blood brain barrier and

enhance satiety signaling, slow gastric emptying, and increase

insulin production. It is likely that numerous mechanisms actually

contribute to the metabolic eff ect of this surgical procedure.

Th ere are several variants of the RYGB. In procedures performed

via a laparoscopic approach, the pouch is completely transected

and separated from the gastric remnant, whereas in the prior

open approach, a staple line merely separates the stomach. Gastro-

jejunal anastomosis (GJA) can be created with circular or linear

staplers, or using a hand-sewn. When sutures are used, these can

Complications of Bariatric Surgery: What You Can

Expect to See in Your GI Practice

Allison R. Schulman , MD 1 , 2 and Christopher C. Th ompson , MD, MSc, FASGE, FACG AGAF 1 , 2

Obesity is one of the most signifi cant health problems worldwide. Bariatric surgery has become one of the fastest

growing operative procedures and has gained acceptance as the leading option for weight-loss. Despite improvement

in the performance of bariatric surgical procedures, complications are not uncommon. There are a number of

unique complications that arise in this patient population and require specifi c knowledge for proper management.

Furthermore, conditions unrelated to the altered anatomy typically require a different management strategy. As

such, a basic understanding of surgical anatomy, potential complications, and endoscopic tools and techniques for

optimal management is essential for the practicing gastroenterologist. Gastroenterologists should be familiar with

these procedures and complication management strategies. This review will cover these topics and focus on major

complications that gastroenterologists will be most likely to see in their practice.

Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112:1640–1655; doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.241; published online 15 August 2017

1 Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital , Boston , Massachusetts , USA ; 2 Harvard Medical School , Boston ,

Massachusetts , USA . Correspondence: Christopher C. Thompson, MD, MSc, FACG, FASGE, AGAF, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy,

Brigham and Women's Hospital , 75 Francis St, ASB II , Boston , Massachusetts 02115 , USA . E-mail: [email protected] Received 27 January 2017 ; accepted 27 June 2017

CME

Complications of Bariatric Surgery

© 2017 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

RE

VIE

W

1641

be absorbable or non-absorbable. In some procedures, a silastic

ring is placed at the level of the GJA in an eff ort to enhance dura-

bility. In addition, placement of the Roux limb can be performed

antegastric (“antecolic”) or retrogastric (“retrocolic”). Jejunojeju-

nal anastomosis can be constructed in an end-to-side or side-to-

side confi guration. Furthermore, limb lengths vary considerably

depending on the operator. All of these variants have specifi c

implications to the risk profi le of the RYGB ( Table 1 ).

Anastomotic ulceration

Ulceration at the GJA, also known as marginal ulceration, is

a common complication of RYGB, occurring in up to 16% of

patients. It can occur anytime postoperatively. It is diagnosed by

upper endoscopy and is typically located on the jejunal aspect of

the GJA ( Figure 2a ). Patients are oft en asymptomatic, suggesting

the incidence may be much higher. When symptoms do occur,

they can include epigastric pain, obstructive symptoms, or gastro-

intestinal bleeding. Further complications include stenosis and

rarely perforation.

Th e etiology of marginal ulceration is likely multifactorial

( 9–12 ). While the mechanisms underlying the development of this

complication have not been fully elucidated, there is substantial

evidence that acidity plays a signifi cant role in the disease patho-

physiology. Poor local tissue perfusion from ischemia or tension at

the site of the anastomosis, in addition to foreign materials (e.g.,

suture, staple), microvascular ischemia from smoking or poorly

controlled diabetes, and medications including but not limited to

non-steroidal anti-infl ammatories (NSAIDs) also play an impor-

tant role in ulcer development. Furthermore, surgical technique

may be relevant, with the majority of studies demonstrating higher

rates of marginal ulceration with the use of circular staplers and

non-absorbable sutures ( 13,14 ). However, the incidence varies

greatly between clinical series utilizing the same surgical tech-

nique, further supporting a multifactorial etiology to the devel-

opment of marginal ulceration. While the relationship between

Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of marginal

ulceration is controversial, a recent nationwide analysis suggests a

strong association ( 15–21 ). A complete list of predisposing factors

is shown in Table 2 .

Th e majority of patients with marginal ulceration respond to

medical therapy which includes high dose proton pump inhibi-

tors (PPIs) and oft entimes the addition of sucralfate solution (not

tablets), especially as adjunctive therapy or in patients already tak-

ing a PPI at the time the ulcer is discovered ( 22 ). Administration

of a soluble or open capsule form of PPI is essential as it allows

enhanced absorption in the Roux limb and common channel due

to increased gastrointestinal transit time post-RYGB, and this

method of administration has been shown to signifi cantly decrease

time to ulcer healing and overall healthcare utilization ( 23 ). Smok-

ing cessation and indefi nite discontinuation of NSAIDs are also

important to promote healing. Removal of foreign material such as

sutures and staples should also be performed if RYGB surgery was

Laparoscopicadjustablegastric banding(LAGB)

Roux-en-Ygastric bypass(RYGB)

a

b c

d e f

Retrocolicgastric bypass Antecolic

gastric bypass

Sleevegastrectomy

Verticalbandedgastroplasty

Figure 1 . Overview of bariatric surgeries. Bariatric surgeries including Roux-en-Y gastric bypass ( a ) with retrocolic ( b ) and antecolic ( c ) anatomy, gastric

banding ( d ), sleeve gastrectomy ( e ), and vertical banded gastroplasty ( f ) ( 136 )*. * with permission.

Schulman and Thompson

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 112 | NOVEMBER 2017 www.nature.com/ajg

RE

VIE

W1642

Table 1 . Complications of common bariatric procedures

Type of

Surgery

Complication Symptom(s) *Time of

onset since

surgery

Diagnostic tips Management strategies

RYGB

Anastomotic ulceration Epigastric pain

N/V

Bleeding

Often

asymptomatic

Early or late Do not advance endoscope deeply

beyond area of ulceration

H. pylori stool antigen or serology

High-dose PPI (soluble form) +/−

sucralfate

Stop smoking

No NSAIDs

Consider suture removal

Anastomotic stenosis Dysphagia

N/V

Malnutrition

Late Upper endoscopy

Avoid UGI series given aspiration risk

Look for concomitant ulceration

Stepwise endoscopic balloon dilation

Do not over-dilate (≤15 mm)

Carefully direct wire into distal Roux

limb

Foreign body removal

LAMS for concomitant ulceration

Gastrogastric fi stula Weight regain

Epigastric pain

Refl ux

N/V

Anytime Upper GI series sensitive

EGD important to confi rm and rule

out ulceration

If asymptomatic: PPI+dietary

counseling

If symptomatic: closure (endoscopic

[<1 cm] vs. surgical)

Surgical leaks Tachycardia

C-reactive protein

Leukocytosis

Post-operative

or early

Cross-sectional imaging

High false negative rates for all

studies

Depends on location of leak and

timing since surgery; see text

Stents for acute pouch and GJ leaks

Clips for JJ leaks

Chronic walled-off leaks treat like

necrosectomy

Intestinal obstruction Abdominal pain (often

intermittent)

N/V

Anytime Cross-sectional imaging while the

patient is symptomatic

Surgery

Endoscopy is not indicated for extra-

luminal causes of obstruction

Choledocholithiasis Right upper quadrant

abdominal pain

Late RUQ u/s

Cross-sectional imaging

MRCP

Device-assisted enteroscopy, laparo-

scopic-assisted ERCP, possible EUS

directed ERCP

Dilated gastrojejunal

anastomosis

Weight regain Late Upper endoscopy

Dilation confi rmed with GJA>15 mm

Endoscopic revision (TORe)

APC for compliant yet not markedly

dilated GJA

LAGB

Refl ux esophagitis GERD Late Upper endoscopy High-dose PPI +/− sucralfate

Band defl ation

Esophageal dilitation Dysphagia

Refl ux

Epigastric discomfort

Late Upper endoscopy

Upper GI series

Band defl ation

Surgical replacement or conversion

Band erosion Pain

N/V

Weight loss

Sepsis

Late Upper endoscopy Endoscopic removal of band if

buckle is visible, with surgical

removal of port

Band slippage Vomiting

Epigastric pain

Late UGI Surgery

Sleeve gastrectomy

Sleeve stenosis Dysphagia,

N/V

Abdominal pain

Anytime Distinguish between stenosis and

twisting; consider imaging

Endoscopic pyloric dilation (hydro-

static to 20 mm) and pneumatic

balloon dilation of sleeve (starting at

30 mm)

Twisted sleeves less likely to respond

Sleeve leaks Tachycardia

C-reactive protein

Leukocytosis

Post-operative

or early

Cross-sectional imaging Depends on timing since surgical

procedure; see text

Acute: stent

Chronic: treat like necrosectomy

Esophageal pathology GERD Late Upper endoscopy High dose PPI +/− sucralfate

Surgical conversion to RYGB

Table 1 continued on following page

Complications of Bariatric Surgery

© 2017 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

RE

VIE

W

1643

performed at least six weeks prior, and this can be accomplished

by the use of biopsy or rat-tooth forceps, or endoscopic scissors

( 24 ). Testing for H. pylori is also recommended, and should be

accomplished by fecal antigen, or serology in immunocompetent

patients who are treatment naïve, as in our experience pouch biop-

sies and breath tests are less reliable in this patient population as

the majority of the stomach where H. pylori resides is inaccessible.

Independent of etiology, we recommend repeat endoscopy in two

to three months to confi rm ulcer healing. Of note, marginal ulcer-

ation complicated by stenosis is particularly diffi cult to manage,

and more likely to require surgical intervention.

Endoscopic suturing techniques in the treatment of recalcitrant

marginal ulceration have demonstrated technical feasibility, safety,

and effi cacy in small series, although additional studies regard-

ing durability are needed ( 25 ). Surgical revision is performed in a

small percentage of patients who do not improve with maximum

medical management, in whom endoscopic techniques are not

successful, or in whom perforation has occurred ( 26 ). Unfortu-

nately, reoperation carries signifi cant morbidity and a 7.7% recur-

rence rate ( 27 ).

Anastomotic stenosis

Stenosis of the GJA is perhaps the most common complications

in RYGB and has been reported in as many as 20% of patients,

however, the majority of studies report incidence in the single dig-

its ( 28–39 ) ( Figure 2b ). Patients can present from weeks to years

post-operatively with progressive dysphagia, nausea, vomiting,

and malnutrition. Some patients may paradoxically have weight

gain as they convert to higher calorie full liquid diets. While the

exact mechanism of stenosis is unknown, ulceration and ischemia

at the GJA, in addition to subclinical anastomotic leak, and

smaller diameter circular staplers used during the initial surgery

are likely contributory factors ( 37–39 ).

Although there is no precise defi nition for stomal stenosis, the

diagnosis is typically made when a patient is symptomatic and

a standard upper endoscope is unable to pass through the GJA.

Endoscopic balloon dilation is fi rst-line for management of this

condition ( Figure 3 ). As the GJA is an end-to-side anastomosis

with a thin jejunal wall directly behind the gastric aspect, care

must be taken to advance the balloon into the Roux limb proper

without traumatizing the adjacent jejunum or blind portion of

the Roux limb. If resistance is met despite careful repositioning,

a fl exible wire may be used as a guide, and rarely an ultrathin

upper endoscope may be required to assist in wire advancement.

Some patients will require multiple procedures to achieve dura-

ble results, and the procedure is safe with a complication rate of

<3% ( 31–33,35,40 ). Dilation should be performed with the goal

of achieving symptom resolution and a durable stomal diameter

of roughly 8–12 mm. Dilation above 15 mm should be performed

in rare circumstances where the patient remains symptomatic

despite having achieved a stable anastomotic diameter that

allows endoscope passage without resistance. Dilation to larger

diameters is associated with increased complications including

perforation and weight regain. It is important to exercise cau-

tion in the setting of coexistent marginal ulceration because this

may increase the risk of perforation and are more likely to require

surgical revision.

Other therapeutic techniques to treat stomal stenosis have also

been described including needle-knife electroincision, intral-

esional steroid injection, and placement of lumen apposing metal

stent ( 41–43 ), the latter of which is particularly helpful in concom-

itant ulceration ( Figure 3 ). Surgical revision for refractory stenosis

is required in approximately two percent of cases ( 44 ).

Gastrogastric fi stula

An abnormal connection between the gastric pouch and the

excluded stomach is known as a gastrogastric fi stula (GGF)

( Figure 2c ). Th ere are several postulated etiologies for the

development of this complication, including surgical technique

without complete division or transection of the gastric pouch,

marginal ulceration, anastomotic leak, and foreign body ero-

sion ( 45–47 ).

Table 1 . Continued

Type of

Surgery

Complication Symptom(s) *Time of

onset since

surgery

Diagnostic tips Management strategies

VBG

Anastomotic stenosis Dysphagia

N/V

Malnutrition

Late Upper endoscopy Endoscopic balloon dilation

Staple line dehiscence Weight regain Anytime Upper endoscopy Surgery

Band erosion Pain

N/V

Weight loss

Sepsis

Late Upper endoscopy Endoscopic removal if band is

silastic

APC, argon plasma coagulation; GERD, gastroesophageal refl ux disease; GJA, gastrojejunal anastomosis; LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; MRCP, mag-

netic resonance cholangiopancreatography; RUQ, right upper quadrant; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; UGI, upper gastrointestinal series.

*Post-operative: immediate post-operative period; early: <30 days; late: ≥30 days.

Schulman and Thompson

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 112 | NOVEMBER 2017 www.nature.com/ajg

RE

VIE

W1644

persistent symptoms clearly attributable to the fi stula. Tradition-

ally, this has been accomplished with surgical revision. However,

newer per-oral approaches using endoscopic suturing systems

carry decreased morbidity, and sustain successful closure in ~20%

of patients at 12 months ( 49,50 ). Endoscopic repair is especially

eff ective when the fi stula is less than one centimeter ( 50,51 ). Sur-

gical revision following unsuccessful suturing appears to be safe.

Use of over-the-scope clips has also been reported, but should be

used with caution, as unlike with endoscopic suturing techniques,

these may interfere with subsequent revision surgery should it be

required ( 52–54 ).

Surgical leaks

Leaks are among the most serious complications and typically

occur within days of the procedure, but can also present in a

more delayed fashion. Th e incidence ranges from 0.1 to 5.6 per-

cent, and is much higher following revision surgery ( 55–58 ).

Th e typical presenting symptom is weight regain or inability to

lose weight as food does not bypass the remnant stomach. Pain,

refl ux, nausea, emesis, and marginal ulceration are also oft en

reported ( 43,48 ). Th e diagnosis is most reliably made by upper gas-

trointestinal series or upper endoscopy, although cross-sectional

imaging can also demonstrate this fi nding ( Figure 4a,b ). Never-

theless, there is a high false positive rate with this approach, as con-

trast can refl ux into the remnant stomach from the duodenum. A

defi nitive diagnosis should be reserved for when an actual fi stula

is seen, and not just contrast in the remnant stomach. Once con-

fi rmed, high dose PPI should be administered to prevent gastric

acid production in the remnant stomach from entering the gastric

pouch and jejunum through the GGF, as this can lead to abdomi-

nal pain and development of marginal ulceration, and potential

stenosis ( Figure 2d ).

GGF may be managed conservatively with PPI therapy and

dietary counseling. Closure is indicated when the patient has

a b

c d

>30 mm

e f

Figure 2 . Endoscopic examples of gastric bypass complications. Endoscopic examples of complications of gastric bypass including marginal ulceration

( a ), stenosis of the gastrojejunal anastomosis ( b ), gastrogastric fi stula (single arrow) with gastrojejunal anastomosis (double arrow) ( c ), gastrogastric fi stula

(triple arrows) complicated by marginal ulceration leading to stenosis of gastrojejunal anastomosis (single arrow) ( d ), staple line leak in gastric pouch ( e ),

and dilated gastrojejunal anastomosis ( f ).

Complications of Bariatric Surgery

© 2017 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

RE

VIE

W

1645

Tachycardia, leukocytosis, and elevated C-reactive protein are

the most common presenting fi ndings, and any one of these

should trigger appropriate supportive care and an expedited

evaluation ( 59 ).

Th ese leaks can occur at multiple points along any staple line

including the gastric pouch ( Figure 2e ), the GJA, the blind por-

tion of the Roux limb, the jejunojejunal anastomosis, and the rem-

nant stomach ( Figure 5 ). Before any therapy is undertaken, it is

important to identify the location of the leak using cross sectional

imaging or combined endoscopic and fl uoroscopic interrogation

of possible sites, as that will dictate the appropriate management.

In addition, it is important to treat downstream obstruction and

remove foreign material from the leak site. Th is includes staples,

sutures, and drains that may be in close proximity.

Endoscopic placement of self-expandable metal stents is eff ec-

tive in the treatment of proximal leaks of the pouch or GJA that

occur in the acute setting ( 60–70 ). Stent migration occurs in

16.9% of patients with rare serious complication ( 58 ). Optimal

time for stent removal is between 6 and 8 weeks, with leak reso-

lution rate of 87.8% ( ref. 58 ). Stents are the preferred treatment

method for leaks in these locations, as it is eff ective and there

is less evidence for the use of other modalities. In chronic leaks

with a walled-off cavity, these modalities are less eff ective, and

treating the collection as walled-off necrosis and ultimately plac-

ing plastic double pigtail stents between the cavity and the gastric

lumen (as detailed below in the sleeve gastrectomy section) is

oft en required ( 71,72 ).

Leaks at other locations are typically not amenable to stent-

ing. Other therapeutic options include clips, over-the-scope clips,

endoscopic suturing, tissue sealants and biochemical matrices.

Th ese modalities have variable results, and the evidence for their

use is limited to case series ( 68,73–75 ).

Table 2 . Etiology of Marginal Ulceration

Predisposing factors

Surgical Technique

Smoking

NSAID use

Alcohol

Lack of PPI use

Factors implicated in the physiopathology

H. pylori

Infl ammation

Foreign body reaction

Acid secretion

Bile refl ux

Fistula

Ischemia

NSAID, non-steroidal anti-infl ammatory.

*Reproduced from Fernandez-Esparrach G, Guarner-Argente C, and Bordas

JM. Ulceration in the Bariatric Patient. Bariatric Endoscopy . Springer

Science+Business Media; 2013, with permission.

a b

c d e

Figure 3 . Management of stenosis of the gastrojejunal anastomosis in gastric bypass. Endoscopic management of stenosis of the gastrojejunal anastomosis

without ulceration ( a ) with balloon dilation ( b ); endoscopic management of stenosis of the gastrojejunal anastomosis with ulceration ( c ) placement of a

lumen apposing metal stent ( d ), and resolution of stenosis and subsequent ulcer healing ( e ).

Schulman and Thompson

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 112 | NOVEMBER 2017 www.nature.com/ajg

RE

VIE

W1646

Intestinal obstruction

Early post-operative bowel obstruction following gastric bypass

occurs at similar rates to other abdominal surgeries. Late bowel

obstruction will be more commonly seen in a gastroenterology

practice, and includes ventral incisional and internal hernias,

adhesions, and intussusceptions ( 76,77 ).

Adhesions and ventral incisional hernias occur more commonly

following open gastric bypass surgery. Both of these entities pre-

sent with pain or obstructive symptoms, with the latter classically

also causing a visible bulge. Internal hernias, on the other hand,

are more common following a laparoscopic surgical approach, and

have a reported incidence of 3–16% ( ref. 78–81 ). Th ere are three

mesenteric defects created during RYGB through which hernias

occur including the jejuno-jejunostomy, the space between the

transverse mesocolon and Roux-limb mesentary (i.e., Peterson’s

defect), and in the transverse mesocolon in patients with a retro-

colic Roux-limb. Computed tomography (CT) may demonstrate

swirled vessels or fat at the root of the mesentary ( Figure 4c ), a

fi nding which is known to have the highest sensitivity and speci-

fi city for making the diagnosis. However, these oft en occur inter-

mittently making radiographic detection diffi cult, and therefore

imaging should be performed while the patient is symptomatic

and there should be a low threshold for re-exploration is indicated

in bariatric patients with unexplained pain or symptoms of bowel

obstruction ( 82 ). If left undetected, bowel necrosis can occur

requiring large segment bowel resection.

a

b

c d

Figure 4 . Radiographic examples of gastric bypass complications. Computed tomography ( a ) and upper gastrointestinal series ( b ) demonstrating evidence

of gastrogastric fi stula; computed tomography demonstrating internal hernia ( c ) with arrows showing swirled vessels and fat at the root of the mesentary

and ( d ) intussusception with arrows showing telescoping of bowel.

Gastric pouch

1

5

4

2

3Remnantstomach

Roux limb

Biliopancreaticlimb (75–150 cm)

Commonlimb

Cecum

Duodenum

Commonbile duct

Gastrojejunostomy

Blind limb

Jejuno-jejunal anastomosis

Ligamentof Treitz

Figure 5 . Multiple points of gastric leak following RYGB.

Complications of Bariatric Surgery

© 2017 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

RE

VIE

W

1647

Intussusception is most commonly seen at the jejunojejunal

anastomosis, where the common limb telescopes through in a

retrograde fashion (distal to proximal) ( Figure 4d ). Th e reported

incidence rates range from 0.1 to 1%, and it oft en presents with sig-

nifi cant weight loss ( 80,83,84 ). Th e etiology is not well understood

but appears to be multifactorial, possibly involving a lead point

(suture lines, food boluses or adhesions), motility disturbances,

or thinning of intestinal mesentery that occurs with weight loss

and allows increased mobility of the bowel and an unstable region

around the site of the Roux limb ( 80,83,84 ). Endoscopy is not typi-

cally useful in these patients.

Cholelithiasis

Gallstone disease is common following RYGB. It is estimated

to occur in 28 to 71 percent of patients within six months fol-

lowing surgery, and as many as 40 percent of these patients are

symptomatic ( 85 ). Rapid weight loss may increase the choles-

terol saturation in the bile and the gallbladder mucin concentra-

tion, increasing the risk of gallstone development. Postoperative

anatomical changes and compromised gallbladder emptying

may also play a role ( 85–90 ). In addition, cholecystectomy is less

commonly performed in the era of laparoscopic RYGB. As such,

gastroenterologists are seeing these patients more frequently.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is

particularly arduous in RYGB anatomy due to the relative inac-

cessibility of the duodenum and ampulla, making treatment

of choledocholithiasis challenging. Surgical technique plays in

important role in likelihood of success, as long a Roux limbs and

side-to-side jejunojejunal anastomosis poses even more diffi -

culty to the endoscopist. Oft entimes the procedure is attempted

using a pediatric colonoscope, spiral overtube, balloon-assisted

enteroscope, or a duodenoscope back-loaded onto a guidewire.

Balloon-assisted enteroscopy is the most well described pro-

cedure, with pooled procedural success rates of 62% ( ref. 91 ).

Alternative approaches include passage through a gastrogastric

fi stula if present with dilation if necessary, placement of a pro-

phylactic gastrostomy tube into the bypassed stomach, or EUS-

directed gastrostomy ( 92 ). A controversial emerging procedure is

the endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric ERCP (EDGE)

procedure, where a lumen-apposing metal stent is placed through

the gastric pouch and into the remnant stomach to allow access.

Th is stent is later removed and carries a risk of a persistent gastro-

gastric fi stula ( 93,94 ).

Failure to lose weight or weight regain

RYGB is associated with 15–35% failure, defi ned as inability to

achieve signifi cant weight loss (>50% loss of excess weight) or

excessive weight regain aft er initial adequate weight loss ( 8,95–98 ).

A signifi cant minority of these patients experience substantial

weight regain even two years post-surgical aft er RYGB ( 8,96–99 ).

In addition, studies have demonstrated that, on average, patients

have regained one third of the maximum weight lost 10 years fol-

lowing RYGB ( 100 ). Dietary non-compliance is contribute known

risk factor for weight regain. It has also been demonstrated that

anatomical changes such as dilation of the GJA ( Figure 2f ), and

development of gastrogastric fi stula ( Figure 2c,d ) play a signifi -

cant role in promoting weight regain ( 101 ).

Endoscopic suturing, plication devices, argon plasma coagula-

tion and other forms of thermal therapy ( 102–106 ) used to tighten

the stoma and reduce pouch volume have proven to be technically

feasible and safe, with recent studies showing sustained weight loss

at three years, and suturing demonstrating level I evidence in a

randomized sham-controlled trial ( 107 ). Th ese endoscopic thera-

pies off er a less invasive treatment option for post-bypass weight

regain, with minimal morbidity.

Nutritional abnormalities

Metabolic and nutritional defi ciencies are not uncommon fol-

lowing RYGB, as reconfi guration of gastrointestinal anatomy,

alteration in motility, pH and enzymatic profi les can lead to

derangements. Th ere should be a low threshold to evaluate and

treat nutritional defi ciencies aggressively. Common nutritional

defi ciencies and clinical symptoms are shown in Table 3 .

Dumping syndrome

Dumping syndrome following RYGB occurs when large quanti-

ties of simple carbohydrates are ingested. Early dumping occurs

within 15 min of ingestion and has been attributed to rapid fl uid

shift s from the plasma into the bowel due to hyperosmolality of

the food. Symptoms include both gastrointestinal complaints

(abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloating, and nausea) and vasomotor

changes (fl ushing, palpitations, perspiration, tachycardia, hypo-

tension, and syncope). Treatment includes avoidance of foods that

are high in simple sugar content, in addition to small frequent

meals in which liquids and solids are separated. Late dumping

results from hyperglycemia and the subsequent insulin response

leading to hypoglycemia, and occurs several hours aft er eating

with resultant symptoms due to low serum glucose (perspiration,

palpitations, weakness, confusion, tremor, and syncope). Treat-

ment includes similar dietary modifi cation, with medications

such as acarbose, an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, reserved for

non-responders. Each of these conditions may present as a spec-

trum of symptoms captured by the Sigstad scoring system ( 108 ).

Abdominal pain

Abdominal pain is one of the most common reasons for gastro-

enterology consultation in the post-surgical population and is

not unique to gastric bypass. A standard abdominal pain work-

up evaluating potential etiologies unrelated to bariatric surgery

should be pursued as appropriate. Th ere are also several etiolo-

gies specifi c to post-surgical anatomy that must be considered.

Patient history and physical examination are oft en essential in

making the diagnosis. Careful evaluation for a Carnett’s sign is

important, as abdominal wall pain is common. Carnett’s sign is

elicited by having the patient lie fl at on an examination table, and

identify the point of maximal abdominal tenderness ( 109 ). Th e

physician then focally compresses this area with continuous pres-

sure and instructs the patient to lift their legs off the table, tens-

ing abdominal musculature. If the focal pain intensifi es, this is a

positive sign suggesting an abdominal wall syndrome. Th e most

Schulman and Thompson

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 112 | NOVEMBER 2017 www.nature.com/ajg

RE

VIE

W1648

line diagnostic study. Endoscopy may also be therapeutic if pain

is due to retained foreign body such as suture material ( 24 ). If the

pain is intermittent, positional, or severe, cross-sectional imaging

should be initially performed to evaluate for potential intestinal

obstruction such as volvulus, intussusception, or internal hernia.

common treatment for abdominal wall pain is trigger point injec-

tion, whereby a local anesthetic is injected directly into the site of

pain. Prioritization of diagnostic studies depends on presenting

symptoms. If consistent mid-epigastric pain is present suggesting

marginal ulceration, upper endoscopy is recommended as a fi rst

Table 3 . Common nutritional defi ciencies and symptoms in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

Defi ciency Common symptoms

Fat-soluble vitamins

Vitamin A Conjunctival dryness

Retinopathy

Night blindness

Dermatologic changes

Immune system impairment

Vitamin D Often asymptomatic (if mild-moderate)

Demineralization of bones, osteomalacia (if severe)

Weakness

Fracture

Vitamin E Neuromuscular disorders

Hemolytic anemia

Vitamin K Impaired coagulation leading to bruisability, mucosal bleeding.

Prolonged prothrombin time (PT)

Water-soluble vitamins

Thiamine (vitamin B1) Wernicke encephalopathy (encephalopathy and confabulation, oculomotor

dysfunction, ataxia)

Vitamin B12 Pernicious (megaloblastic) anemia

Folate Megaloblastic anemia

Vitamin C Petechiae

Gingivitis

Arthralgias

Poor wound healing

Trace minerals

Iron Hypochromic, microcytic anemia

Zinc Impotence

Impaired immune function

Hair loss

Copper Microcytic anemia

Neutropenia

Ataxia

Selenium Skeletal muscle dysfunction

Cardiomyopathy

Other

Calcium Metabolic bone disease

Secondary hyperparathyroidism

Protein Protein energy malnutrition

Complications of Bariatric Surgery

© 2017 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

RE

VIE

W

1649

Th is imaging should ideally be performed when the patient is

symptomatic, which increases the sensitivity. Right upper quad-

rant pain may warrant ultrasound, cross-sectional imaging, or

magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) to evalu-

ate for cholelithiasis or cholodocholithiasis as a fi rst line test.

For diff use or lower abdominal discomfort, abdominal bloating,

and change in bowel habits, hydrogen or methane breath tests to

evaluate for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) should

also be part of the work-up. Th ese studies may be fraught with false

positives, as there is also faster transit time in RYGB patients ( 110 ).

As such, transit time to the colon should be estimated by small

bowel follow-through, and the breath test evaluated in light of

patient specifi c results. If the pain is generalized or predominantly

in the left upper quadrant, enteroscopy to the remnant stomach

may also be considered to look for remnant gastropathy or other

gastric remnant pathology. Th is is critical in patients that also

have unexplained anemia. For patients without anemia and who

are high risk for procedural intervention, we recommend obtain-

ing cholescintigraphy (99mTc-heapto-iminodiacetic acid (HIDA)

scanning), which allows for a radiolabeled substance to be taken

up selectively by hepatocytes and excreted into bile, thereby pro-

viding information about bile fl ow. Pooling of bile in the remnant

stomach suggests a positive test. Recent studies suggest that this

may off er a non-invasive alternate diagnostic strategy for iden-

tifying increased risk for bile acid gastropathy ( 111 ). If refl ux to

the remnant stomach is noted, then use of ursodiol, in addition

to PPI therapy, has been shown to eff ectively treat this condition

in small studies, and we have found it to be a useful management

strategy ( 111 ).

Surgical management

For chronic marginal ulceration or gastro-gastric fi stula, revision

of RYGB reconstituting the normal RYGB anatomy is being per-

formed more commonly and safely. Reversal of RYGB is an option

for patients with excessive weight loss, dumping syndrome, per-

sistent nausea and emesis. Esophagojejunostomy is reserved for

persistent leaks in the proximal pouch as it is a relatively morbid

procedure. Surgical revisions for weight regain, including Roux

limb distalization, are also performed when less invasive options

are not successful.

LAPAROSCOPIC ADJUSTABLE GASTRIC BANDING

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding involves the insertion of

an adjustable, prosthetic band over the cardia of the stomach to

form a gastric pouch with roughly 15 ml capacity ( Figure 1b ). Th e

mechanism of action for this procedure is primarily restrictive in

nature. Th e gastric band consists of a silicone ring connected to

an infusion port, the latter of which remains in the subcutaneous

tissue and can be easily accessed for fl uid injection to increase the

degree of restriction, thus rendering it fl exible to meet the chang-

ing needs of the patient. While this procedure has the lowest peri-

operative complication rate and mortality among all bariatric

procedures, there are several disadvantages including presence of

a foreign body.

Refl ux esophagitis

Acid refl ux and esophagitis are common following banding

procedures ( 112–115 ) ( Figure 6a ). A systematic review demon-

strated newly developed refl ux symptoms aft er gastric banding in

up to 50% of patients without prior symptoms, and new esophagi-

tis confi rmed in up to 38.4% ( ref. 113 ). Treatment involves acid-

suppression therapy with or without sucralfate, as well as referral

to a surgeon for potential defl ation of the band.

Esophageal dilation

An achalasia-like syndrome can occur in less than ten percent

of patients and results from esophageal dilation proximal to the

band ( 116–119 ) ( Figure 6b ). Excessive fi lling of the band can

precipitate this condition and cause symptoms of refl ux, epigas-

tric discomfort, and inability to tolerate oral intake. Treatment

involves fl uid removal via the subcutaneous port (“band holiday”)

with reevaluation in 6 weeks ( 120 ). If this is not eff ective, replace-

ment of the band in a new location, or conversion to an alternative

bariatric procedure, is the typical course of action.

Band erosion

Band erosion, or intragastric migration, occurs in less than

6.8 percent of patients ( 121 ). Mean time to occurrence of 22.5

months post operatively, with a range of weeks to years ( 121,122 ).

Early erosions are usually attributed to undetected perforations

during surgery or early infection, while late erosions may be the

a b c

Figure 6 . Endoscopic examples of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding complications. Severe refl ux esophagitis ( a ), pseudoachalasia following lap-

band placement ( b ) and lap band erosion ( c ).

Schulman and Thompson

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 112 | NOVEMBER 2017 www.nature.com/ajg

RE

VIE

W1650

( refs 129,130 ). Over-sewing the staple line or use of a bougie that

is too small both predispose to narrowing at these locations. Rota-

tion of the stomach during stapling can also lead to a twisted and

narrowed sleeve.

Symptoms of obstruction can occur depending on the sever-

ity of the narrowing. Th is diagnosis is typically made by endo-

scopy or upper gastrointestinal series, and endoscopic dilation

is the primary mode of management. We recommend starting

with a hydrostatic balloon, and dilating both the pylorus and the

incisura to 20 mm. If there is no symptomatic improvement, use

of a pneumatic dilation balloon is then recommended at the level

of the gastric stenosis. We recommend starting with a 30 mm bal-

loon. Depending on resistance, maximal PSI may not be reached

in the fi rst session. In two weeks the procedure is repeated with

the same size balloon if maximum PSI was not reached, or with

a balloon fi ve mm greater in size. Th is process is repeated every

two weeks as needed until symptoms resolve ( Figure 7 ). A recent

study has demonstrated 96% effi cacy when using this algorithm

( 131 ). It is important to ensure the pneumatic balloon is not span-

ning the gastroesophageal junction or the pylorus to minimize risk

of perforation. If the sleeve is twisted, this technique is oft en less

eff ective.

Sleeve leaks

One complication that is common and particularly bothersome

is leak following sleeve gastrectomy. Th is complication has been

reported in up to 5.3 percent of patients, and usually occur along

the superior aspect of the staple line just below the gastroesopha-

geal junction ( 132 ). Th ese patients present in a more delayed fash-

ion than aft er RYGB.

Endoscopic approaches have proven successful, and off er a

less invasive fi rst line therapy for many patients. Th e timing of

presentation for sleeve leaks aff ects management strategy and

the literature supports diff erent time cut-off s in this regard.

If the leak occurs early (i.e., within six weeks following sleeve

gastrectomy) we recommend stent placement with simultane-

ous dilation of the pylorus to treat downstream obstruction. If

the leak is delayed and the collection is walled-off ( Figure 8 ),

we instead recommend dilation of the pylorus and distal sleeve,

and approach the collection in a manner similar to endoscopic

necrosectomy technique ( 71,72 ). In this approach, an endo-

scope is advanced into the collection and is used to mechani-

cally debride non-viable tissue and perform antibiotic lavage

with subsequent placement of pigtail stents for ongoing drain-

age. Other centers report use of a needle-knife fenestration

technique ( 133,134 ). Both of these approaches allow healing by

secondary intention.

Gastroesophageal refl ux disease and Barrett’s esophagus

Sleeve gastrectomy may predispose to esophageal pathology

including gastroesophageal refl ux disease and Barrett’s esopha-

gus. While some studies have failed to consistently demonstrate

an association, new evidence suggests that patients who have

undergone sleeve gatrectomy may be at substantially higher risk

of developing these complications. A recent study found that the

consequence of gastric wall ischemia from an excessively tight

band. Clinical manifestations of this complication can include

refl ux, nausea and vomiting, epigastric pain, excessive weight loss,

and life-threatening sepsis. In addition, if the site of erosion occurs

into the posterior part of the stomach near the cardioesophageal

junction, massive hematemesis can occur from involvement of the

gastric artery ( 123 ). Th e fi nding of abdominal cellulitis (overlying

the port) also indicates likely band erosion and warrants further

investigation. Diagnosis can be made endoscopically ( Figure 6c ),

and if the band buckle is visible, removal may be accomplished at

the time of the procedure, using a stiff guidewire and mechanical

lithotripter ( 124,125 ). Th is requires the patient to be under gen-

eral anesthesia, and that a surgeon is available to remove the sub-

cutaneous port (which can be performed in endoscopy). Th e wire

is fed through the opening of the band and the ends are placed

into the mechanical lithotripter. Th e band is then severed and can

be pulled out through the mouth.

Band slippage

Band slippage leads to prolapse of a portion of the stomach

through the band, and is one of the most common and bother-

some late complications of gastric banding. Patients oft en present

with vomiting and epigastric pain, and should prompt surgical

consultation.

Port infection or malfunction

Th e mechanical port component of the adjustable band device

exposes the patients to infectious complications given the pres-

ence of a foreign body, in addition to the inevitable consequences

of device weathering, which can lead to its failure ( 126–128 ).

Endoscopy is of no therapeutic value in this setting.

Surgical management

Laparoscopic adjustable banding can be easily reversed with

endoscopic or surgical removal of the band. Th is is oft en done for

failure of effi cacy or the aforementioned complications. Conver-

sion to other bariatric procedures such as sleeve gastrectomy or

RYGB is commonly and safely performed.

SLEEVE GASTRECTOMY

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is a procedure in which a large

portion of the greater curvature of the stomach is removed, leav-

ing just a small conduit along the lesser curvature. In so doing,

this procedure eff ectively removes fundal ghrelin-producing cells

and increases gastric emptying, which is associated with a vari-

ety of metabolic consequences leading to weight loss ( Figure 1c ).

Mechanistically, ghrelin levels decrease following sleeve gastrec-

tomy, and this is believed to aff ect appetite regulation. In addi-

tion, hind gut mechanisms including post-prandial increase in

Peptide-YY and GLP-1 are thought to play a role ( 6–8 ).

Sleeve stenosis

Stenosis following sleeve gastrectomy classically occurs at the

incisura ( Figure 7 ). Th e incidence is reported to be 0.7–4%

Complications of Bariatric Surgery

© 2017 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

RE

VIE

W

1651

incidence of GERD symptoms signifi cantly increased compared

with preoperative values (68.1% vs. 33.6%). Furthermore, PPI intake

similarly increased following surgery (57.2% vs. 19.1%). Finally,

a signifi cant increase in the incidence and severity of erosive

esophagitis was evidenced, and a signifi cant number of patients

were diagnosed with non-dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus ( 135 ).

As the prevalence of sleeve gastrectomy increases, the develop-

ment of these conditions should be monitored closely.

Surgical management

For complications not amenable to endoscopic or medical therapy,

surgical options are available. For refractory severe erosive

a b

c

Figure 7 . Management of stenosis of the incisura in sleeve gastrectomy. Sleeve gastrectomy complicated by stenosis of the incisura with pooling of bile

acid ( a ) managed by pneumatic balloon dilation under endoscopic ( b ) and fl uroscopic ( c ) guidance.

a b

Figure 8 . Management of late leak in sleeve gastrectomy. Sleeve gastrectomy complicated by late leak presenting with contained walled-off necrosis ( a )

managed by debridement and subsequent stent placement through leak site (arrow) ( b ).

Schulman and Thompson

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 112 | NOVEMBER 2017 www.nature.com/ajg

RE

VIE

W1652

Financial support: None.

Potential competing interests: C.C. Th ompson—Apollo Endo-

surgery (Consultant/Research Support); Olympus (Consultant/

Research Support); Boston Scientifi c (Consultant); Covidien (Con-

sultant, Royalty, Stock); Medtronic (Consultant, Royalty, Stock);

USGI Medical (Consultant/Research Support). Th e remaining

author declares no confl ict of interest.

REFERENCES 1. Buchwald H , Avidor Y , Braunwald E et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic

review and meta-analysis . JAMA 2004 ; 292 : 1724 – 37 . 2. Arterburn DE , Olsen MK , Smith VA et al. Association between bariatric

surgery and long-term survival . JAMA 2015 ; 313 : 62 . 3. Buchwald H , Oien DM . Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011 .

Obes Surg 2013 ; 23 : 427 – 36 . 4. Perry CD , Hutter MM , Smith DB et al. Survival and changes in comor-

bidities aft er bariatric surgery . Ann Surg 2008 ; 247 : 21 – 7 . 5. Colquitt JL , Clegg AJ , Loveman E et al. Surgery for morbid obesity . In:

Colquitt JL editor(s). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews John Wiley & Sons, Ltd : Chichester, UK , 2005 , pp CD003641 .

6. Ramón JM , Salvans S , Crous X et al. Eff ect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy on glucose and gut hormones: a prospective ran-domised trial . J Gastrointest Surg 2012 ; 16 : 1116 – 22 .

7. Peterli R , Steinert RE , Woelnerhanssen B et al. Metabolic and hormonal changes aft er laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrec-tomy: a randomized, prospective trial . Obes Surg 2012 ; 22 : 740 – 8 .

8. Magro DO , Geloneze B , Delfi ni R et al. Long-term weight regain aft er gastric bypass: A 5-year Prospective Study . Obes Surg 2008 ; 18 : 648 – 51 .

9. Azagury DE , Abu Dayyeh BK , Greenwalt IT et al. Marginal ulceration aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: characteristics, risk factors, treat-ment, and outcomes . Endoscopy 2011 ; 43 : 950 – 4 .

10. Dallal RM , Bailey LA . Ulcer disease aft er gastric bypass surgery . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006 ; 2 : 455 – 9 .

11. Rasmussen JJ , Fuller W , Ali MR . Marginal ulceration aft er laparoscopic gastric bypass: an analysis of predisposing factors in 260 patients . Surg Endosc 2007 ; 21 : 1090 – 4 .

12. Coblijn UK , Lagarde SM , de Castro SMM et al. Symptomatic marginal ulcer disease aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: incidence, risk factors and management . Obes Surg 2015 ; 25 : 805 – 11 .

13. Edholm D , Sundbom M . Comparison between circular- and linear-stapled gastrojejunostomy in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass—a cohort from the Scandinavian Obesity Registry . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015 ; 11 : 1233 – 6 .

14. Sacks BC , Mattar SG , Qureshi FG et al. Incidence of marginal ulcers and the use of absorbable anastomotic sutures in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006 ; 2 : 11 – 16 .

15. Schirmer B , Erenoglu C , Miller A . Flexible endoscopy in the management of patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Obes Surg 2002 ; 12 : 634 – 8 .

16. Cleator IG , Rae A , Birmingham CL . Ulcerogenesis following gastric procedure for obesity . Obes Surg 1996 ; 6 : 260 – 1 .

17. Papasavas PK , Gagné DJ , Donnelly PE et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and value of preoperative testing and treatment in patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2008 ; 4 : 383 – 8 .

18. Lin Y-S , Chen M-J , Shih S-C et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection aft er gastric surgery . World J Gastroenterol 2014 ; 20 : 5274 .

19. Hartin CW , ReMine DS , Lucktong TA . Preoperative bariatric screening and treatment of Helicobacter pylori . Surg Endosc 2009 ; 23 : 2531 – 4 .

20. Rawlins L , Rawlins MP , Brown CC et al. Eff ect of Helicobacter pylori on marginal ulcer and stomal stenosis aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013 ; 9 : 760 – 4 .

21. Schulman AR , Abougergi M , Th ompson CCH . Pylori as a predictor of marginal ulceration: a nationwide analysis . Obesity 2017 ; 25 : 522 – 6 .

22. Carr WRJ , Mahawar KK , Balupuri S et al. An evidence-based algorithm for the management of marginal ulcers following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Obes Surg 2014 ; 24 : 1520 – 7 .

23. Schulman AR , Chan WW , Devery A et al. Opened proton pump inhibitor capsules reduce time to healing compared with intact capsules for marginal ulceration following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016 ; 15 : 494 – 500.e1 .

esophagitis or persistent dysphagia due to a stenosed or twisted

sleeve, conversion to RYGB is a successful option. For patients

who lose inadequate weight or develop weight regain following

sleeve gastrectomy, conversion to RYGB or duodenal switch (i.e.,

sleeve with distal small bowel anastomosis) is a viable option.

VERTICAL BANDED GASTROPLASTY

Vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG) is a purely restrictive proce-

dure that involves the creation of a small proximal gastric pouch

<50 ml lined by a vertical staple line and a tight prosthetic mesh

that is sutured to itself but not the stomach ( Figure 1d ). Th is sur-

gery has the benefi t of providing an outlet diameter that remains

constant.

Familiarity with the complications of this procedure is impor-

tant, despite the fact that VBG has largely been replaced by other

procedures. Staple line dehiscence can result in formation of a fi s-

tula to the fundus, oft en leading to weight gain. Th is type of fi stula

is found in as many as half of all patients on routine post-operative

endoscopy. Stomal stenosis can also occur and present as obstruc-

tive symptoms, and be managed by endoscopically by balloon

dilation, although results are oft en short-lived and revision may

be necessary. Band erosion is a late complication of VBG, and can

be removed via endoscopy if the band is silastic. Removal of mesh

bands is typically not feasible. All of these complications warrant

consideration for surgical revision.

Surgical management

Th is procedure is most commonly converted to a RYGB when

there is inadequate weight loss, as the proximal stomach has been

modifi ed into a pouch.

CONCLUSION

Obesity is one of the most signifi cant health problems worldwide.

Despite improvement in the performance of bariatric surgical

procedures, complications are not uncommon. It is our respon-

sibility as gastroenterologists to be familiar with these procedures

and complication management strategies. In addition, primary

endoscopic therapies for obesity are seeing broader use in the

United States. As obesity is one of the most challenging medical

and economic problems faced by our society, fellowship programs

should place a greater emphasis on the management of this con-

dition and procedure-related complications. Endoscopy is a less

invasive alternative to primary and revisional procedures, and

will have a signifi cant role in the care of these patients moving

forward.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Christopher C. Th ompson, MD, MSc,

FACG, FASGE, AGAF.

Specifi c author contributions: Draft ing of the manuscript: Allison

R. Schulman; this author has approved the fi nal draft submitted.

editing of the manuscript: Christopher C. Th ompson; this author has

approved the fi nal draft submitted.

Complications of Bariatric Surgery

© 2017 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

RE

VIE

W

1653

24. Ryou M , Mogabgab O , Lautz DB et al. Endoscopic foreign body removal for treatment of chronic abdominal pain in patients aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010 ; 6 : 526 – 31 .

25. Jirapinyo P , Watson RR , Th ompson CC . Use of a novel endoscopic sutur-ing device to treat recalcitrant marginal ulceration (with video) . Gastro-intest Endosc 2012 ; 76 : 435 – 9 .

26. Chau E , Youn H , Ren-Fielding CJ et al. Surgical management and outcomes of patients with marginal ulcer aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2015 ; 11 : 1071 – 5 .

27. Patel RA , Brolin RE , Gandhi A . Revisional operations for marginal ulcer aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009 ; 5 : 317 – 22 .

28. Schneider BE , Villegas L , Blackburn GL et al. Laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery: outcomes . J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech 2003 ; 13 : 247 – 55 .

29. Awad S , Aguilo R , Agrawal S et al. Outcomes of linear-stapled versus hand-sewn gastrojejunal anastomosis in laparoscopic Roux en-Y gastric bypass . Surg Endosc 2015 ; 29 : 2278 – 83 .

30. Sanyal AJ , Sugerman HJ , Kellum JM et al. Stomal complications of gastric bypass: incidence and outcome of therapy . Am J Gastroenterol 1992 ; 87 : 1165 – 9 .

31. Ahmad J , Martin J , Ikramuddin S et al. Endoscopic balloon dilation of gastroenteric anastomotic stricture aft er laparoscopic gastric bypass . Endoscopy 2003 ; 35 : 725 – 8 .

32. Peifer KJ , Shiels AJ , Azar R et al. Successful endoscopic management of gastrojejunal anastomotic strictures aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Gastrointest Endosc 2007 ; 66 : 248 – 52 .

33. Nguyen NT , Stevens CM , Wolfe BM . Incidence and outcome of anas-tomotic stricture aft er laparoscopic gastric bypass . J Gastrointest Surg 2003 ; 7 : 997 – 1003 ; discussion 1003 .

34. Huang CS . Th e role of the endoscopist in a multidisciplinary obesity center . Gastrointest Endosc 2009 ; 70 : 763 – 7 .

35. Barba CA , Butensky MS , Lorenzo M et al. Endoscopic dilation of gastroesophageal anastomosis stricture aft er gastric bypass . Surg Endosc 2003 ; 17 : 416 – 20 .

36. Podnos YD , Jimenez JC , Wilson SE et al. Complications aft er laparoscopic gastric bypass: a review of 3464 cases . Arch Surg 2003 ; 138 : 957 – 61 .

37. Gould JC , Garren M , Boll V et al. Th e impact of circular stapler diameter on the incidence of gastrojejunostomy stenosis and weight loss following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Surg Endosc 2006 ; 20 : 1017 – 20 .

38. Fisher BL , Atkinson JD , Cottam D . Incidence of gastroenterostomy stenosis in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass using 21- or 25-mm circular stapler: a randomized prospective blinded study . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007 ; 3 : 176 – 9 .

39. Giordano S , Salminen P , Biancari F et al. Linear stapler technique may be safer than circular in gastrojejunal anastomosis for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a meta-analysis of comparative studies . Obes Surg 2011 ; 21 : 1958 – 64 .

40. Go MR , Muscarella P , Needleman BJ et al. Endoscopic management of stomal stenosis aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Surg Endosc 2004 ; 18 : 56 – 9 .

41. Majumder S , Buttar N , Gostout C et al. Lumen-apposing covered self-expanding metal stent for management of benign gastrointestinal strictures . Endosc Int Open 2015 ; 4 : E96 – 101 .

42. Uchima H , Abu-Suboh M , Mata A et al. Lumen-apposing metal stent for the treatment of refractory gastrojejunal anastomotic stricture aft er laparoscopic gastric bypass . Gastrointest Endosc 2016 ; 83 : 251 .

43. Lee JK , Van Dam J , Morton JM et al. Endoscopy is accurate, safe, and eff ective in the assessment and management of complications following gastric bypass surgery . Am J Gastroenterol 2009 ; 104 : 575 – 82 ; quiz 583 .

44. Campos JM , de Mello FST , Ferraz AAB et al. Endoscopic dilation of gastrojejunal anastomosis aft er gastric bypass . Arq Bras Cir Dig 2012 ; 25 : 283 – 9 .

45. Tucker ON , Szomstein S , Rosenthal RJ . Surgical management of gastro-gastric fi stula aft er divided laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity . J Gastrointest Surg 2007 ; 11 : 1673 – 9 .

46. Pauli EM , Beshir H , Mathew A . Gastrogastric fi stulae following gastric bypass surgery—clinical recognition and treatment . Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014 ; 16 : 405 .

47. Stanczyk M , Deveney C , Traxler S et al. Gastro-gastric fi stula in the era of divided Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: strategies for prevention, diagnosis, and management . Obes Surg 2006 ; 16 : 359 – 64 .

48. Huang CS , Forse RA , Jacobson BC et al. Endoscopic fi ndings and their clinical correlations in patients with symptoms aft er gastric bypass sur-gery . Gastrointest Endosc 2003 ; 58 : 859 – 66 .

49. Mukewar S , Kumar N , Catalano M et al. Safety and effi cacy of fi stula closure by endoscopic suturing: a multi-center study . Endoscopy 2016 ; 48 : 1023 – 8 .

50. Fernandez-Esparrach G , Lautz DB , Th ompson CC . Endoscopic repair of gastrogastric fi stula aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a less-invasive approach . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010 ; 6 : 282 – 8 .

51. Haito-Chavez Y , Law JK , Kratt T et al. International multicenter experi-ence with an over-the-scope clipping device for endoscopic management of GI defects (with video) . Gastrointest Endosc 2014 ; 80 : 610 – 22 .

52. Niland B , Brock A . Over-the-scope clip for endoscopic closure of gastro-gastric fi stulae . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2016 ; 13 : 15 – 20 .

53. Flicker MS , Lautz DB , Th ompson CC . Endoscopic management of gastrogastric fi stulae does not increase complications at bariatric revision surgery . J Gastrointest Surg 2011 ; 15 : 1736 – 42 .

54. Law R , Wong Kee Song LM , Irani S et al. Immediate technical and delayed clinical outcome of fi stula closure using an over-the-scope clip device . Surg Endosc 2015 ; 29 : 1781 – 6 .

55. Nelson DW , Blair KS , Martin MJ . Analysis of obesity-related outcomes and bariatric failure rates with the duodenal switch vs gastric bypass for morbid obesity . Arch Surg 2012 ; 147 : 847 – 54 .

56. Gonzalez R , Nelson LG , Gallagher SF et al. Anastomotic leaks aft er laparoscopic gastric bypass . Obes Surg 2004 ; 14 : 1299 – 307 .

57. Almahmeed T , Gonzalez R , Nelson LG et al. Morbidity of anastomotic leaks in patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Arch Surg 2007 ; 142 : 954 .

58. Puli SR , Spoff ord IS , Th ompson CC . Use of self-expandable stents in the treatment of bariatric surgery leaks: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Gastrointest Endosc 2012 ; 75 : 287 – 93 .

59. Mickevicius A , Sufi P , Heath D . Factors predicting the occurrence of a gastrojejunal anastomosis leak following gastric bypass . Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2014 ; 3 : 436 – 40 .

60. Salinas A , Baptista A , Santiago E et al. Self-expandable metal stents to treat gastric leaks . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006 ; 2 : 570 – 2 .

61. Fukumoto R , Orlina J , McGinty J et al. Use of Polyfl ex stents in treatment of acute esophageal and gastric leaks aft er bariatric surgery . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007 ; 3 : 68 – 71-2 .

62. Eisendrath P , Cremer M , Himpens J et al. Endotherapy including tempo-rary stenting of fi stulas of the upper gastrointestinal tract aft er laparo-scopic bariatric surgery . Endoscopy 2007 ; 39 : 625 – 30 .

63. Serra C , Baltasar A , Andreo L et al. Treatment of gastric leaks with coated self-expanding stents aft er sleeve gastrectomy . Obes Surg 2007 ; 17 : 866 – 72 .

64. Casella G , Soricelli E , Rizzello M et al. Nonsurgical treatment of staple line leaks aft er laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy . Obes Surg 2009 ; 19 : 821 – 6 .

65. Eubanks S , Edwards CA , Fearing NM et al. Use of endoscopic stents to treat anastomotic complications aft er bariatric surgery . J Am Coll Surg 2008 ; 206 : 935 – 8-9 .

66. Babor R , Talbot M , Tyndal A . Treatment of upper gastrointestinal leaks with a removable, covered, self-expanding metallic stent . Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2009 ; 19 : e1 – e4 .

67. Edwards CA , Bui TP , Astudillo JA et al. Management of anastomotic leaks aft er Roux-en-Y bypass using self-expanding polyester stents . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2008 ; 4 : 594 – 9-600 .

68. Merrifi eld BF , Lautz D , Th ompson CC . Endoscopic repair of gastric leaks aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a less invasive approach . Gastrointest Endosc 2006 ; 63 : 710 – 4 .

69. Kriwanek S , Ott N , Ali-Abdullah S et al. Treatment of gastro-jejunal leak-age and fi stulization aft er gastric bypass with coated self-expanding stents . Obes Surg 2006 ; 16 : 1669 – 74 .

70. Ballesta C , Berindoague R , Cabrera M et al. Management of anasto-motic leaks aft er laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Obes Surg 2008 ; 18 : 623 – 30 .

71. Th ompson CC , Kumar N , Slattery J et al. A standardized method for endoscopic necrosectomy improves complication and mortality rates . Pancreatology 2016 ; 16 : 66 – 72 .

72. Kumar N , Conwell DL , Th ompson CC . Direct endoscopic necrosectomy versus step-up approach for walled-off pancreatic necrosis: comparison of clinical outcome and health care utilization . Pancreas 2014 ; 43 : 1334 – 9 .

73. Jacobsen GR , Coker AM , Acosta G et al. Initial experience with an inno-vative endoscopic clipping system . Surg Technol Int 2012 ; 22 : 39 – 43 .

74. Ritter LA , Wang AY , Sauer BG et al. Healing of complicated gastric leaks in bariatric patients using endoscopic clips . JSLSSoc Laparoendosc Surg 2013 ; 17 : 481 – 3 .

75. Seebach L , Bauerfeind P , Gubler C . "Sparing the surgeon": clinical experience with over-the-scope clips for gastrointestinal perfora-tion . Endoscopy 2010 ; 42 : 1108 – 11 .

Schulman and Thompson

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 112 | NOVEMBER 2017 www.nature.com/ajg

RE

VIE

W1654

102. Baretta GAP , Alhinho HCAW , Matias JEF et al. Argon plasma coagulation of gastrojejunal anastomosis for weight regain aft er gastric bypass . Obes Surg 2015 ; 25 : 72 – 9 .

103. Abu Dayyeh BK , Jirapinyo P , Weitzner Z et al. Endoscopic sclerotherapy for the treatment of weight regain aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: outcomes, complications, and predictors of response in 575 procedures . Gastrointest Endosc 2012 ; 76 : 275 – 82 .

104. Th ompson CC , Slattery J , Bundga ME et al. Peroral endoscopic reduc-tion of dilated gastrojejunal anastomosis aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a possible new option for patients with weight regain . Surg Endosc 2006 ; 20 : 1744 – 8 .

105. Mullady DK , Lautz DB , Th ompson CC . Treatment of weight regain aft er gastric bypass surgery when using a new endoscopic platform: initial experience and early outcomes (with video) . Gastrointest Endosc 2009 ; 70 : 440 – 4 .

106. Jirapinyo P , Slattery J , Ryan MB et al. Evaluation of an endoscopic sutur-ing device for transoral outlet reduction in patients with weight regain following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Endoscopy 2013 ; 45 : 532 – 6 .

107. Kumar N , Th ompson CC . Transoral outlet reduction for weight regain aft er gastric bypass: long-term follow-up . Gastrointest Endosc 2016 ; 83 : 776 – 9 .

108. Sigstad H . A clinical diagnostic index in the diagnosis of the dumping syndrome. Changes in plasma volume and blood sugar aft er a test meal . Acta Med Scand 1970 ; 188 : 479 – 86 .

109. Carnett J . Intercostal neuralgia as a cause of abdominal pain and tender-ness . Surg Gynecol Obs 1926 ; 42 : 625 – 32 .

110. Abidi W , Chan WW , Th ompson CC . Breath testing for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients: the impor-tance of orocecal transit time . Gastroenterology 2016 ; 150 : S688 – 9 .

111. Schulman AR , Th ompson CC . Utility of bile acid scintigraphy in the diagnosis of remnant gastritis in patients with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Gastrointest Endosc 2016 ; 83 : AB327 – 8 .

112. Naik RD , Choksi YA , Vaezi MF . Impact of weight loss surgery on esophageal physiology . Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2015 ; 11 : 801 – 9 .

113. de Jong JR , Besselink MGH , van Ramshorst B et al. Eff ects of adjustable gastric banding on gastroesophageal refl ux and esophageal motility: a systematic review . Obes Rev 2010 ; 11 : 297 – 305 .

114. Gamagaris Z , Patterson C , Schaye V et al. Lap-band impact on the func-tion of the esophagus . Obes Surg 2008 ; 18 : 1268 – 72 .

115. Dixon JB , O’Brien PE . Gastroesophageal refl ux in obesity: the eff ect of lap-band placement . Obes Surg 1999 ; 9 : 527 – 31 .

116. Naef M , Mouton WG , Naef U et al. Esophageal dysmotility disorders aft er laparoscopic gastric banding--an underestimated complication . Ann Surg 2011 ; 253 : 285 – 90 .

117. Dargent J . Esophageal dilatation aft er laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: defi nition and strategy . Obes Surg 2005 ; 15 : 843 – 8 .

118. Arias IE , Radulescu M , Stiegeler R et al. Diagnosis and treatment of meg-aesophagus aft er adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009 ; 5 : 156 – 9 .

119. Khan A , Ren-Fielding C , Traube M . Potentially reversible pseudoacha-lasia aft er laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding . J Clin Gastroenterol 2011 ; 45 : 775 – 9 .

120. Fielding GA . Should the lap band be removed to treat pseudoachalasia? Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013 ; 9 : 471 – 3 .

121. Suter M , Giusti V , Héraief E et al. Band erosion aft er laparoscopic gastric banding: occurrence and results aft er conversion to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Obes Surg 2004 ; 14 : 381 – 6 .

122. Abu-Abeid S , Keidar A , Gavert N et al. Th e clinical spectrum of band erosion following laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding for morbid obesity . Surg Endosc 2003 ; 17 : 861 – 3 .

123. Png KS , Rao J , Lim KH et al. Lap-band causing left gastric artery erosion presenting with torrential hemorrhage . Obes Surg 2008 ; 18 : 1050 – 2 .

124. Neto MPG , Ramos AC , Campos JM et al. Endoscopic removal of eroded adjustable gastric band: lessons learned aft er 5 years and 78 cases . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010 ; 6 : 423 – 7 .

125. Blero D , Eisendrath P , Vandermeeren A et al. Endoscopic removal of dysfunctioning bands or rings aft er restrictive bariatric procedures . Gastrointest Endosc 2010 ; 71 : 468 – 74 .

126. Abu-Abeid S , Szold A . Results and complications of laparoscopic adjust-able gastric banding: an early and intermediate experience . Obes Surg 1999 ; 9 : 188 – 90 .

76. Swanson CM , Roust LR , Miller K et al. What every hospitalist should know about the post-bariatric surgery patient . J Hosp Med 2012 ; 7 : 156 – 63 .

77. Carucci LR , Turner MA . Imaging aft er bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding . Semin Roentgenol 2009 ; 44 : 283 – 96 .

78. Higa KD , Ho T , Boone KB . Internal hernias aft er laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: incidence, treatment and prevention . Obes Surg 2003 ; 13 : 350 – 4 .

79. Higa K , Ho T , Tercero F et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year follow-up . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2011 ; 7 : 516 – 25 .

80. Hamdan K , Somers S , Chand M . Management of late postoperative complications of bariatric surgery . Br J Surg 2011 ; 98 : 1345 – 55 .

81. Blachar A , Federle MP . Gastrointestinal complications of laparoscopic roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery in patients who are morbidly obese: fi ndings on radiography and CT . AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002 ; 179 : 1437 – 42 .

82. Ma IT , Madura JA . Gastrointestinal complications aft er bariatric surgery . Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2015 ; 11 : 526 – 35 .

83. Simper SC , Erzinger JM , McKinlay RD et al. Retrograde (reverse) jejunal intussusception might not be such a rare problem: a single group’s experi-ence of 23 cases . Surg Obes Relat Dis 2008 ; 4 : 77 – 83 .

84. Daellenbach L , Suter M . Jejunojejunal intussusception aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a review . Obes Surg 2011 ; 21 : 253 – 63 .

85. Shiff man ML , Sugerman HJ , Kellum JM et al. Gallstone formation aft er rapid weight loss: a prospective study in patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery for treatment of morbid obesity . Am J Gastroenterol 1991 ; 86 : 1000 – 5 .

86. Shiff man ML , Sugerman HJ , Kellum JM et al. Changes in gallbladder bile composition following gallstone formation and weight reduction . Gastro-enterology 1992 ; 103 : 214 – 21 .

87. Worobetz LJ , Inglis FG , Shaff er EA . Th e eff ect of ursodeoxycholic acid therapy on gallstone formation in the morbidly obese during rapid weight loss . Am J Gastroenterol 1993 ; 88 : 1705 – 10 .

88. Iglézias Brandão de Oliveira C , Adami Chaim E , da Silva BB . Impact of rapid weight reduction on risk of cholelithiasis aft er bariatric surgery . Obes Surg 2003 ; 13 : 625 – 8 .

89. Bastouly M , Arasaki CH , Ferreira JB et al. Early changes in postprandial gallbladder emptying in morbidly obese patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: correlation with the occurrence of biliary sludge and gallstones . Obes Surg 2009 ; 19 : 22 – 8 .

90. Everhart JE . Contributions of obesity and weight loss to gallstone disease . Ann Intern Med 1993 ; 119 : 1029 – 35 .

91. Inamdar S , Slattery E , Sejpal DV et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of single-balloon enteroscopy-assisted ERCP in patients with surgically altered GI anatomy . Gastrointest Endosc 2015 ; 82 : 9 – 19 .

92. Th ompson CC , Ryou MK , Kumar N et al. Single-session EUS-guided transgastric ERCP in the gastric bypass patient . Gastrointest Endosc 2014 ; 80 : 517 .

93. Kedia P , Kumta N , Widmer J et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric ERCP (EDGE) for Roux-en-Y anatomy: a novel technique . Endoscopy 2015 ; 47 : 159 – 63 .

94. Tyberg A , Nieto J , Salgado S et al. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-directed transgastric endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or EUS: mid-term analysis of an emerging procedure . Clin Endosc 2016 ; 50 : 185 – 90 .

95. Monaco-Ferreira DV , Leandro-Merhi VA . Weight regain 10 years aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Obes Surg 2016 ; 27 : 1137 – 44 .

96. Nicoletti CF , de Oliveira BAP , de Pinhel MAS et al. Infl uence of excess weight loss and weight regain on biochemical indicators during a 4-year follow-up aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Obes Surg 2015 ; 25 : 279 – 84 .

97. Christou NV , Look D , MacLean LD . Weight gain aft er short- and long-limb gastric bypass in patients followed for longer than 10 years . Ann Surg 2006 ; 244 : 734 – 40 .

98. Barhouch AS , Padoin AV , Casagrande DS et al. Predictors of excess weight loss in obese patients aft er gastric bypass: a 60-month follow-up . Obes Surg 2016 ; 26 : 1178 – 85 .

99. Lim CSH , Liew V , Talbot ML et al. Revisional bariatric surgery . Obes Surg 2009 ; 19 : 827 – 32 .

100. Sjöström L , Lindroos A-K , Peltonen M et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years aft er bariatric surgery . N Engl J Med 2004 ; 351 : 2683 – 93 .

101. Abu Dayyeh BK , Lautz DB , Th ompson CC . Gastrojejunal stoma diameter predicts weight regain aft er Roux-en-Y gastric bypass . Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011 ; 9 : 228 – 33 .

Complications of Bariatric Surgery

© 2017 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

RE

VIE

W

1655

132. Burgos AM , Braghetto I , Csendes A et al. Gastric leak aft er laparoscopic-sleeve gastrectomy for obesity . Obes Surg 2009 ; 19 : 1672 – 7 .

133. Mahadev S , Kumbhari V , Campos JM et al. Endoscopic septotomy: an eff ective approach for internal drainage of sleeve gastrectomy-associated collections . Endoscopy 2017 ; 49 : 504 – 8 .