Colorectal cancer following negative colonoscopy: is 5-year screening the correct interval to...

Transcript of Colorectal cancer following negative colonoscopy: is 5-year screening the correct interval to...

Colorectal cancer following negative colonoscopy: is 5-yearscreening the correct interval to recommend?

Steven K. Nakao • Steven Fassler • Iswanto Sucandy •

Soo Kim • D. Mark Zebley

Received: 23 April 2012 / Accepted: 13 August 2012 / Published online: 10 October 2012

� Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2012

Abstract

Background Despite the high sensitivity of screening

colonoscopy, polyps and cancers can still go undetected.

With the polyp-to-cancer transformation cycle averaging

7–10 years, present guidelines recommend repeat colon-

oscopy within 10 years after negative screening. However,

not all colorectal malignancies follow this decade-long

progression. This study evaluates the incidence and

pathology of colorectal cancers following a previous neg-

ative screening colonoscopy.

Methods Records of patients who underwent a colectomy

at our institution, from 1998 to 2009, were reviewed ret-

rospectively. A total of 1,784 patient records were screened

using exclusion criteria for inclusion in this study. The

patients were divided as follows: Group 1 included patients

with a negative colonoscopy within the previous 5 years;

Group 2 included patients without a previous colonoscopy

or with a previous colonoscopy more than 5 years prior.

Group 1 patients were evaluated by colonoscopy for ane-

mia, diverticulitis, signs of obstruction, and bleeding. Age,

tumor location, operation performed, and pathology find-

ings were recorded. The v2 test and paired t test were used

for statistical analysis.

Results A total of 233 patients were included in this

study. Group 1 contained 43 patients with a mean age of

73 years (range = 35–94, median = 75). Group 2 had 190

patients with a mean age of 68 years (range = 19–91,

median = 70). Group 1 consisted of 18 male and 25 female

patients, and Group 2 included 94 male and 96 female

patients. Both groups were further classified into the

following age categories: \50 years, 50–80 years, and

[80 years. Eighteen percent of the total study population

had newly discovered colorectal cancer within a 5-year

colonoscopy screening period. There were no significant

differences in the distribution of the T and N stages

between the two groups and no statistically significant

differences when the rate of lymphovascular invasion (19

vs. 17 %; p = 0.39) and perineural invasion (7 vs. 11 %;

p = 0.58) were compared.

Conclusions Within 5 years, 18 % of our study popula-

tion developed colorectal cancer. Most of these malig-

nancies were found within the 50–80-year age group and

located predominantly in the right colon and distally in the

sigmoid and rectum. While distal cancers may be visual-

ized by flexible sigmoidoscopy, those located more prox-

imally may be missed, necessitating the need for a full

colonoscopy. Although staging was similar between the

two groups, Group 1 tumors were less aggressive despite

having appeared within 5 years. As a result of our inci-

dence of colorectal cancer within a 5-year interval, a

shorter period for routine colonoscopy may be considered.

Keywords Colorectal cancer � Endoscopy

Colon cancer remains the third most common cancer

diagnosis and is the second leading cause of cancer-related

death in the US annually [1]. Early detection through

Presented at the SAGES 2012 Annual Meeting, March 7–March 10,

2012, San Diego, CA.

S. K. Nakao � I. Sucandy

Department of Surgery, Abington Memorial Hospital, Abington,

PA, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

S. Fassler (&) � S. Kim � D. M. Zebley

Department of Surgery, Division of Colorectal Surgery,

Colon and Rectal Associates, 1235 Old York Road, Suite G20,

Abington, PA 19001, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

123

Surg Endosc (2013) 27:768–773

DOI 10.1007/s00464-012-2543-6

and Other Interventional Techniques

evidence-based screening protocols can lead to the identi-

fication of early disease [2–5]. Initial screening for colon

cancer can be grouped into two categories: stool-based and

structural tests. Stool-based tests are noninvasive, inex-

pensive, and can be performed in the office; however, they

are highly variable and less sensitive for detection of colon

cancer [2]. Due to the variability in detection, annual or

biennial fecal screening is recommended to detect any stool

changes indicative of colon cancer. Structural tests such as

sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy are more sensitive in

detecting early disease and can be therapeutic.

Screening protocols are tailored for average-risk patients

who do not have a documented family history or predis-

posing history of colon cancer. Studies have shown that

patients who are over the age of 50 years have a higher

incidence of colon cancer than younger patients. Current

guidelines recommend that screening colonoscopy should

begin at age 50 in these average-risk patients and follow-up

depends on the pathology found on examination [3].

Positive and negative examinations are determined by the

presence of adenomatous polyps found on colonoscopy,

and recommendations for repeat screening ranges from 3 to

5 years for a positive exam and 10 years for a negative

exam [4, 5].

While the typical polyp-to-cancer transformation cycle

takes an average of 10 years, not all polyps will follow this

decade-long progression. Therefore, a 10-year interval may

prove too long a period for repeat surveillance after a

negative colonoscopy in normal-risk patients. This study

evaluates the incidence and pathology of colorectal cancers

that arose within 5 years after a negative screening

colonoscopy.

Methods

Medical records of patients who underwent colon resection

from 1998 to 2009 were reviewed retrospectively. Initially,

1,784 patients were included in our database. Those who

were included initially had resection performed at two area

hospitals by the same three colon and rectal surgeons.

Review showed that resection had been performed for

complications from anemia, diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease,

ulcerative colitis, foreign body insertion, high-risk family

history, or new onset cancer. Inclusion criteria for the study

were as follows: those patients operated on at a single

teaching hospital, with no documented family history, and

who were not at a higher risk for colorectal cancer. Using

those criteria, 563 patients were included for initial review

in this study. Of these 563 patients, 300 charts had docu-

mented previous colonoscopic surveillance. Those without

a documented previous colonoscopy were excluded from

the study. Of these 300 patients, 67 were noted to have had

a colonoscopy for continued surveillance after previous

colon cancer resection and also were excluded from the

study. The remaining 233 patients had a documented pre-

vious colonoscopy for reasons other than suspected cancer,

as manifested by pain, bleeding, or signs of obstruction and

made up the study group.

Colonoscopic examinations were performed by two

groups at our institution; both sets of physicians were fel-

lowship-trained gastroenterologists or colorectal surgeons.

The gastroenterology group had an average of 9 years of

clinical and endoscopic experience per physician prior to

the start of this study. The colorectal surgeons had a

minimum of 3 years of clinical and endoscopic experience

prior to the start of this study. The annual endoscopic

experience per physician within each group averaged

[1,000 colonoscopies per doctor. Colonoscopic examina-

tion was considered complete with cecal intubation and, on

average, a 7-min withdrawal time, which had been docu-

mented within the chart review.

Patients who met the criteria for inclusion in the study

were then divided as follows: Group 1 patients had a

documented previously negative colonoscopy within the

last 5 years and were noted to have benign or no pathology

on previous reports. Group 2 patients had a documented

previous colonoscopy more than 5 years prior with similar

benign pathology. Benign pathology was considered as no

polyp found on examination or polyps that did not show

adenomatous features upon histologic evaluation.

The two groups were then divided further into subsets

by age, location, and stage. Male and female ratios were

calculated. Age was categorized as \50 years of age,

between 50 and 80 years of age, and[80 years, with mean

and median points. Tumor location was also identified as

originating in the right, transverse, left, sigmoid colon, or

rectum. Tumor stage, nodal metastasis, and evidence of

distant metastasis were also noted for each of the preceding

locations. Overall clinical stage was then tabulated for each

location and age group. The v2 test and the paired t test

analyses were used to determine statistical significance of

the location and clinical stages between the two groups.

Results

A total of 1,784 patients were initially included in this

study; however, after exclusion criteria were applied, only

233 patients qualified for inclusion (Fig. 1). These 233

patients were divided into two groups depending on their

previous colonoscopy status. Group 1 included those who

had a colonoscopy within the last 5 years and a negative

pathology report; there were 43 patients, with a mean age

of 73 years (range = 35–94, median = 75) and a male-to-

female ratio of 18:25. Two patients were younger than age

Surg Endosc (2013) 27:768–773 769

123

50 years, 28 patients were between 50 and 80 years, and 13

were older than 80 years (Fig. 2).

Location and stage of each tumor were categorized for

each age group as follows: 2 right-sided cancers in the\50-

year age group; 11 right-sided, 1 transverse colon, 2 left-

sided, 7 sigmoid colon, 6 rectal, and 1 synchronous

malignancy (right and left colon) in the 50–80-year age

group; 9 right-sided, 1 sigmoid colon, and 3 rectal tumors in

the[80-year age group (Fig. 3). In the\50-year age group,

100 % of the tumors were characterized as stage I. In the

50–80-year age group, 42.9 % were stage I, 25 % were

stage II, 25 % were stage III, and 7.1 % were stage IV. In

the[80-year group, 30.8 % were stage I, 30.8 % were stage

II, and 38.4 % were stage III (Fig. 4).

In Group 2, there were 190 patients with a mean age of

68 years (range = 19–91, median = 70) and a male-to-

female ratio of 94:96. There were 20 patients\50 years of

age, 133 between 50 and 80 years, and 37 patients

[80 years of age (Fig. 2). There were 6 right-sided, 3 left-

sided, 4 sigmoid colon, and 7 rectal tumors in the\50-year

subset. In patients aged between 50 and 80 years, 44 right-

sided, 5 transverse colon, 12 left-sided, 21 sigmoid colon,

47 rectal, and 4 synchronous tumors were found. In those

[80 years, there were 23 right-sided, 5 left-sided, 1 sig-

moid colon, and 8 rectal tumors (Fig. 3). In the \50-year

age group, 30 % of the tumors were stage I, 20 % were

stage II, and 50 % were stage III. In patients aged

50–80 years, 33.9 % of the tumors were stage I, 35.3 %

were stage II, 29.3 % were stage III, and 1.5 % were stage

IV. In patients[80 years, 32.4 % of the tumors were stage

I, 32.4 % were stage II, and 35.2 % were stage III (Fig. 4).

When comparing tumors in the 50–80-year subset of

both groups, there were no significant differences in their

location in the colon. In Group 1, tumor location was on the

right side in 39.3 %, in the transverse in 3.6 %, on the left

side in 7.1 %, in the sigmoid in 25 %, in the rectum in

21.4 %, and synchronous (right and left sides) in 3.6 %. In

group 2, 33 % were right-sided (p = 0.27), 3.6 % were

transverse (p = 0.01), 9 % were left-sided (p = 0.63),

15.8 % were sigmoid (p = 0.14), 35.2 % were in the

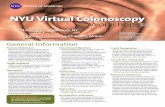

Fig. 1 Algorithm for inclusion in the study

Fig. 2 Age distribution

Fig. 3 Tumor location

Fig. 4 Tumor stage

770 Surg Endosc (2013) 27:768–773

123

rectum (p = 0.9), and 3.6 % were synchronous

(p = 0.001) (Table 1). Tumors in Group 1 were 42.9 %

stage I, 25 % stage II, 25 % stage III, and 7.1 % stage IV.

Tumors in Group 2 were 33.9 % stage I (p = 0.19), 35.3 %

stage II (p = 0.86), 29.3 % stage III (p = 0.68), and 1.5 %

stage IV (p = 0.01) (Table 2). There were no significant

differences in the distribution of the T and N stages

between the two groups. There also were no significant

statistical differences between the two groups when the

rates of lymphovascular invasion (19 vs. 17 %; p = 0.39)

and perineural invasion (7 vs. 11 %; p = 0.58) were

compared.

Discussion

As previously stated, screening for colon cancer can be

approached by one of two methods: fecal or structural-

based. While structural-based tests are the standard for

colon surveillance, lesions can still be missed. Patients who

had previous colonoscopies were included in this study and

divided into groups depending on the interval from previ-

ous colonoscopy. Approximately one in five patients

(18 %) who were diagnosed with colon cancer had a pre-

viously documented negative colonoscopy within the last

5 years. All of these lesions were found in patients who did

not have any previously documented colon cancer or sig-

nificant family history of colon cancer. None of the patients

included in this study had preventative family surveillance

as the reason for colonoscopic screening.

Despite the higher sensitivity of structural screening

examinations, many lesions still go undetected and can

progress to invasive cancer. Typically, lesions found within

3 years after a previously negative colonoscopy are usually

thought to have been missed on the initial screening, while

tumors found more than 3–5 years after the negative

colonoscopy are thought to have appeared de novo [6].

Previous studies have shown that the institution of routine

colonoscopy screening has found adenomas at a rate of

approximately 23 % and that removal of these adenomas

has led to a decrease in the rates of invasive colorectal

cancer [7, 8]. Even the discovery of small adenomas

(\1 cm) on sigmoidoscopy can be a harbinger of high-

grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma in the remaining

colon, and these patients should be referred for a complete

colonoscopy [9]. These studies show the importance of

colonoscopy screening in average-risk patients to decrease

the rates of invasive colon cancer.

Historically, patients between the ages of 50 and

80 years have had the highest incidence of colorectal

cancer or adenomas found on colonoscopy. After the

implementation of colonoscopic screening for these

patients, the incidence of colon malignancies has

decreased. Although this study included the total number of

new incidences of colon cancer, our data for location and

staging reflect mostly the incidence of colon cancer in the

50–80-year age group. A recent study evaluating the age at

which to begin screening average-risk patients for colon

cancer noticed an increase in the incidence of colon cancer

in patients between 20 and 49 years [10]. Staging of these

tumors has shown that they are often times more aggressive

and advanced at the time of diagnosis, with a significant

number of tumors found in the sigmoid colon and rectum

[11, 12]. However, in our study, patients outside the

screening ages (below 50 years and above 80 years of age)

were shown to have a very low incidence of colon cancer.

This trend is likely due to the higher median age of patients

at our institution.

The distribution of colon malignancies in our study

appears quite different from those that are usually descri-

bed in the literature. Previously reported data show that

cancers detected by colonoscopy are typically seen in the

left colon or distally, while right-sided cancers are not

documented with the same frequency [13]. Previously

reported limitations for decreased detection of right-sided

colon cancers have been attributed to difficulty in cecal

intubation, poor quality of bowel preparation, experience

of the endoscopist, history of colon resection, patient

anatomy, or shortened withdrawal time of the colonoscope

[14, 15]. More recent studies have shown that experience

of the endoscopist factors considerably into the rate of

newly diagnosed tumors found on colonoscopy [16]. Rates

of adenoma detection, polyp removal, or completion of a

colonoscopy in women have been shown to affect the rates

of post-colonoscopy malignancies. Numerous studies have

shown an inverse relationship between the rates of polyp/

Table 1 Tumor location in 50–80-year age group

Group 1 Group 2 p value

Right-sided 39.3 % 33 % 0.27

Transverse 3.6 % 3.6 %

Left-sided 7.1 % 9 % 0.63

Sigmoid 25 % 15.8 % 0.14

Rectum 21.4 % 35.2 % 0.9

Synchronous 3.6 % 3.6 %

Table 2 Tumor stage in 50–80-year age group

Group 1 Group 2 p value

Stage I 42.9 % 33.9 % 0.19

Stage II 25 % 35.3 % 0.86

Stage III 25 % 29.3 % 0.68

Stage IV 7.1 % 1.5 % 0.01

Surg Endosc (2013) 27:768–773 771

123

adenoma detection and colonoscopy completion with

malignancy [17–20]. Studies have also shown a higher

incidence of colon cancer after a previously negative

colonoscopy in women. This has been hypothesized to be

the result of a more tortuous colon, incomplete preparation

of the right colon, or estrogen use [21]. In our study, there

is no statistically significant difference between men and

women and there is an increased incidence of right-sided

lesions in both men and women.

Structural and histological differences between right-

and left-sided colon tumors have also been documented.

Right-sided cancers are typically sessile or flat, and the

physiological difference between right- and left-sided

lesions can lead to a difference in progression of a lesion

[22, 23]. In the current study, a higher number of right-

sided colon cancers were detected by colonoscopy in both

Group 1 and Group 2 patients, with fewer left-sided lesions

in Group 1 and an approximately equal number of left-

sided lesions in the Group 2. Patients who present for

routine follow-up colonoscopy demonstrate a higher per-

centage of left-sided and distal colon cancers, which is in

line with previously reported data [23]. Studies have shown

that an increased rate of screening colonoscopy leads to

lower death rates and a decrease in the amount of left-sided

colon cancers that lead to death. More often, right-sided

colon cancers lead to death because of missed lesions on

initial colonoscopy or difference in tumor biology [13–20].

Of those tumors that were detected by colonoscopy,

most that were seen in the Group 1 patients were calculated

to be stage I tumors, with fewer but comparable stage II

and III lesions and few stage IV cancers. Consequently,

those patients who required more frequent colonoscopies

had less invasive tumors at the time of surgery. When

compared to those in Group 2, tumor staging was more

evenly distributed between stages I and III, and this appears

to be more typical of a longer colonoscopic surveillance

[23]. However, there does not appear to be a significant

difference between the stages of colon cancer between the

two groups, implying that neither group had a more

aggressive form of cancer.

This study is limited by several factors. The sample size

from a single institution is, of course, limited and affects

the statistical significance. Second, the patient’s comor-

bidities were not documented in all initial histories thus

limiting any clinical significance to the incidence of colon

cancer. Third, there was no documentation of significant

long-term follow-up after colon cancer resections.

Although current guidelines recommend that colon

cancer screening should commence at age 50 years for

average-risk patients and have a repeat colonoscopy

between 5 and 10 years, our data suggest that this may be

too long an interval, especially with a higher incidence of

right-sided colon cancers. While many of these cancers are

found in lower stages, a decreased screening interval may

lead to earlier detection and thus more complete resection

of colorectal tumors at less invasive states. Having

screening intervals of less than 5 years for benign disease

might be recommended for earlier detection and eradica-

tion of potential colon cancer.

Disclosures Steven K. Nakao, Steven A. Fassler, Iswanto Sucandy,

D. Mark Zebley, and Soo Kim have no conflicts of interest or

financial ties to disclose.

References

1. U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group (2010) United States Cancer

Statistics: 1999–2007 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report.

Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute, Atlanta.

http://www.prevent-cancer.org/ColorectalCancerInformation.aspx

2. Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW (2008) Cancer screening

in the United States, 2008: a review of current American Cancer

Society guidelines and cancer screening issues. CA Cancer J Clin

58:161–179

3. Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, Beil TL, Fu R (2008) Screening for

colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review of the

U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 149:

638–658

4. Walsh JM, Terdiman JP (2003) Colorectal cancer screening: a

scientific review. JAMA 289:1288–1296

5. Lieberman D (2006) Screening for colorectal cancer in average-

risk populations. Am J Med 119:728–735

6. Hosokawa O, Shirasaki S, Kaizaki Y, Hayashi H, Douden K,

Hattori M (2003) Invasive colorectal cancer detected up to

3 years after a colonoscopy negative for cancer. Endoscopy

35(6):506–510

7. Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Seiler CM, Hoffmeister M (2011)

Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after negative colonoscopy.

J Clin Oncol 29:3761–3767

8. Loeve F, Boer R, Zauber AG, van Ballegooijen M, van Oort-

marssen GJ, Winawer SJ (2004) National polyp study data: evi-

dence for regression of adenomas. Int J Cancer 111(4):633–639

9. Butterly LF (2006) What is the clinical importance of small

polyps with regard to colorectal cancer screening? Clin Gastro-

enterol Hepatol 4:343–348

10. Davis DM, Marcet JE, Frattini JC, Prather AD, Mateka J, Nfonsam

VN (2011) Is it time to lower the recommended screening age for

colorectal cancer? J Am Coll Surg 2(13):352–361

11. Robertson DJ, Greenberg ER, Beach M et al (2005) Colorectal

cancer in patients under close colonoscopic surveillance. Gas-

troenterology 129(1):34–41

12. Strock P, Mossong J, Scheiden R, Weber J, Heieck F, Kerschen A

(2011) Colorectal cancer incidence is low in patients following a

colonoscopy. Dig Liver Dis 43:899–904

13. Bressler B, Paszat LF, Vinden C, Li C, He J, Rabeneck L (2004)

Colonoscopic miss rates for right-sided colon cancer: a popula-

tion-based analysis. Gastroenterology 127(2):452–456

14. Soetikno RM, Kaltenbach T, Rouse RV et al (2008) Prevalence of

nonpolypoid (flat and depressed) colorectal neoplasms in

asymptomatic and symptomatic adults. JAMA 299(9):1027–1035

15. Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Altenhofen L,

Haug U (2010) Protection from right- and left-sided colorectal

772 Surg Endosc (2013) 27:768–773

123

neoplasms after colonoscopy: population-based study. J Natl

Cancer Inst 102(2):89–95

16. Heresbach D, Barrioz T, Lapalus MG, Coumaros D, Bauret P,

Potier P (2008) Miss rate for colorectal neoplastic polyps: a

prospective multicenter study of back-to-back video colonos-

copies. Endoscopy 40(4):284–290

17. Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Seiler CM, Rickert A, Hoffmeister

M (2011) Protection from colorectal cancer after colonoscopy.

Ann Intern Med 154:22–30

18. Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wa-

jciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zweirko M, Rupinski M, Nowacki

MP, Butruk E (2010) Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the

risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med 362:1795–1803

19. Singh H, Nugent Z, Mahmud SM, Demers AA, Bernstein CN

(2010) Predictors of colorectal cancer after negative colonoscopy:

a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 105:663–673

20. Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR,

Rabeneck L (2009) Association of colonoscopy and death from

colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med 150:1–8

21. Sugai T, Habano W, Jiao YF et al (2006) Analysis of molecular

alterations in left- and right-sided colorectal carcinomas reveals

distinct pathways of carcinogenesis: proposal for new molecular

profile of colorectal carcinomas. J Mol Diagn 8(2):193–201

22. Azzoni C, Bottarelli L, Campanini N et al (2007) Distinct

molecular patterns based on proximal and distal sporadic colo-

rectal cancer: arguments for different mechanisms in the tumor-

igenesis. Int J Colorectal Dis 22(2):115–126

23. Bressler B, Paszat LF, Chen Z, Rothwell DM, Vinden C, Rabe-

neck L (2007) Rates of new or missed colorectal cancers after

colonoscopy and their risk factors: a population-based analysis.

Gastroenterology 132(1):96–102

Surg Endosc (2013) 27:768–773 773

123