CJASNcjasn.asnjournals.org/site/includefiles/home/RoleoftheMedDir.pdf · Denver, Colorado W. Kline...

Transcript of CJASNcjasn.asnjournals.org/site/includefiles/home/RoleoftheMedDir.pdf · Denver, Colorado W. Kline...

-

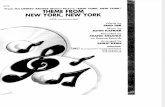

Role of the Medical Director Series

A guide to one of the most important, challenging, and rewarding aspects of the nephrologists professional career, that of the dialysis clinic medical director, is available within this comprehensive 9-part series available now in a user-friendly compiled pdf file.

Series Editors: Jeffrey L. Hymes, MD Robert Provenzano, MD

Deputy Editor:Paul M. Palevsky, MD, FASN

Editor-in-Chief:Gary C. Curhan, MD, ScD, FASN

Providing an invaluable resource for practicing nephrologists and nephrology trainees

CJASNs

CJASN

ASN LEADING THE F IGHTAGAINST KIDNEY DISEASE

-

CJASNClinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

Role of the Medical Director

Article 1 Introduction: Role of the Medical Director Series

Robert Provenzano and Jeffrey L. Hymes

Article 2 The Evolving Role of the Medical Director of a Dialysis Facility

Franklin W. Maddux and Allen R. Nissenson

Article 3 The Medical Director and Quality Requirements in the Dialysis Facility

Brigitte Schiller

Article 4 Maintaining Safety in the Dialysis Facility

Alan S. Kliger

Article 5 Infection Prevention and the Medical Director: Uncharted Territory

Toros Kapoian, Klemens B. Meyer, and Douglas S. Johnson

Article 6 What Medical Directors Need to Know about Dialysis Facility Water Management

Ted Kasparek and Oscar E. Rodriguez

Article 7 The Medical Director in Integrated Clinical Care Models

Thomas F. Parker III and George R. Aronoff

Article 8 Managing Disruptive Behavior by Patients and Physicians: A Responsibility of the DialysisFacility Medical Director

Edward R. Jones and Richard S. Goldman

Article 9 Legal Issues for the Medical Director

William G. Trulove

Article 10 Medical Director Responsibilities to the ESRD Network

Peter B. DeOreo and Jay B. Wish

-

Editors

Editor-in-Chief Gary C. Curhan, MD, ScD, FASNBoston, MA

Deputy Editors Kirsten L. Johansen, MDSan Francisco, CA

Paul M. Palevsky, MD, FASNPittsburgh, PA

Associate EditorsMichael Allon, MDBirmingham, AL

Jeffrey C. Fink, MD, MS, FASNBaltimore, MD

Linda F. Fried, MD, MPH, FASNPittsburgh, PA

David S. Goldfarb, MD, FASNNew York, NY

Donald E. Hricik, MDCleveland, OH

Mark M. Mitsnefes, MDCincinnati, OH

Ann M. OHare, MDSeattle, WA

Mark A. Perazella, MD, FASNNew Haven, CT

Vlado Perkovic, MBBS, PhD, FASN, FRACPSydney, Australia

Katherine R. Tuttle, MD, FACP, FASNSpokane, WA

Sushrut S. Waikar, MDBoston, MA

Section Editors

Attending Rounds Series Editor Mitchell H. Rosner, MD, FASNCharlottesville, VA

Education Series Editor Suzanne Watnick, MDPortland, OR

Ethics Series Editor Alvin H. Moss, MD, FACPMorgantown, WV

Public Policy Series Editor Alan S. Kliger, MDNew Haven, CT

Role of the Medical Director Series Co-Editors Jeffrey L. Hymes, MDNashville, TN

Robert Provenzano, MDDetroit, MI

Statistical EditorsRonit Katz, DPhilSeattle, WA

Robert A. Short, PhDSpokane, WA

Editor-in-Chief, EmeritusWilliam M. Bennett, MD, FASNPortland, OR

Managing EditorShari LeventhalWashington, DC

CJASNClinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

-

Editorial BoardRajiv AgarwalIndianapolis, Indiana

Ziyad Al-AlySaint Louis, Missouri

Charles AlpersSeattle, Washington

Sandra AmaralPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania

Jerry AppelNew York, New York

Arif AsifMiami, Florida

Mohamed AttaBaltimore, Maryland

Joanne BargmanToronto, ON, Canada

Brendan BarrettSt. Johns, NL, Canada

Srinivasan BeddhuSalt Lake City, Utah

Jeffrey BernsPhiladelphia, PA

Geoffrey BlockDenver, Colorado

W. Kline BoltonCharlottesville, Virginia

Andrew BombackNew York, New York

Ursula BrewsterNew Haven, Connecticut

Patrick BrophyIowa City, Iowa

Emmanuel BurdmannSao Paulo, Brazil

Kerri CavanaughNashville, Tennessee

Micah ChanMadison, Wisconsin

Anil ChandrakerBoston, Massachusetts

David CharytanBoston, Massachusetts

Michael ChoiBaltimore, Maryland

Michel ChoncholDenver, Colorado

Steven CocaNew Haven, Connecticut

Andrew DavenportLondon, United Kingdom

Ian de BoerSeattle, Washington

Bradley DixonIowa City, Iowa

Lance DworkinProvidence, Rhode Island

Jeffrey FadrowskiBaltimore, Maryland

Derek FineBaltimore, Maryland

Kevin FinkelHouston, Texas

Steven FishbaneMineola, New York

John FormanBoston, Massachusetts

Lui ForniWorthing, United Kingdom

Barry FreedmanWinston Salem, North Carolina

Masafumi FukagawaKanagawa, Japan

Susan FurthPhiladelphia, PA

Martin GallagherSydney, Australia

Maurizio GallieniMilan, Italy

Ronald GansevoortGroningen, Netherlands

Amit GargLondon, ON, Canada

Michael GermainSpringfield, Massachusetts

Eric GibneyAtlanta, Georgia

John GillVancouver, BC, Canada

David GoldsmithLondon, United Kingdom

Stuart GoldsteinCincinnati, Ohio

Barbara GrecoSpringfield, Massachusetts

Orlando GutierrezBirmingham, Alabama

Yoshio HallSeattle, Washington

Lee HammNew Orleans, Louisiana

Ita HeilbergSao Paulo, Brazil

Brenda HemmelgarnCalgary, AB, Canada

Jonathan HimmelfarbSeattle, Washington

Eric HosteGent, Belgium

Chi-yuan HsuSan Francisco, California

T. Alp IkizlerNashville, Tennessee

Tamara IsakovaChicago, Illinois

Meg JardineSydney, Australia

Michelle JosephsonChicago, Illinois

Bryce KiberdHalifax, BC, Canada

Greg KnollOttawa, ON, Canada

Jay KoynerChicago, Illinois

Holly KramerMaywood, Illinois

Manjula Kurella TamuraPalo Alto, California

Hiddo Lambers HeerspinkGroningen, Netherlands

Craig LangmanChicago, Illinois

James LashChicago, Illinois

Eleanor LedererLouisville, Kentucky

Andrew LewingtonLeeds, United Kingdom

Orfeas LiangosCoburg, Germany

Fernando LianoMadrid, Spain

John LieskeRochester, Minnesota

Kathleen LiuSan Francisco, California

Randy LucianoNew Haven, Connecticut

Jicheng LvBeijing, China

Mark MarshallAuckland, New Zealand

William McClellanAtlanta, Georgia

Anita MehrotraNew York, New York

Rajnish MehrotraSeattle, Washington

Michal MelamedBronx, New York

Sharon MoeIndianapolis, Indiana

Barbara MurphyNew York, New York

Nader NajafianBoston, Massachusetts

Andrew NarvaBethesda, Maryland

Sankar NavaneethanCleveland, Ohio

Alicia NeuBaltimore, Maryland

Thomas NickolasNew York, New York

Toshiharu NinomiyaFukuoka, Japan

Rainer OberbauerVienna, Austria

Gregorio ObradorMexico

Runolfur PalssonReykjavik, Iceland

Mandip PanesarBuffalo, New York

Neesh PannuEdmonton, Canada

Rulan ParekhBaltimore, Maryland

Uptal PatelDurham, North Carolina

Aldo PeixotoWest Haven, Connecticut

Anthony PortaleSan Francisco, California

Jai RadhakrishnanNew York, New York

Mahboob RahmanCleveland, Ohio

Dominic RajWashington, District of Columbia

Peter ReesePhiladelphia, Pennsylvania

Giuseppe RemuzziBergamo, Italy

Mark RosenbergMinneapolis, Minnesota

Andrew RuleRochester, Minnesota

Jeffrey SalandNew York, New York

Jane SchellPittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Bernd SchroppelUlm, Germany

Stephen SeligerBaltimore, Maryland

Michael ShlipakSan Francisco, California

Edward SiewNashville, Tennessee

Theodore SteinmanBoston, Massachusetts

Peter StenvinkelStockholm, Sweden

Harold SzerlipAugusta, Georgia

Eric TaylorBoston, Massachusetts

Ashita TolwaniBirmingham, Alabama

James TumlinChattanooga, Tennessee

Mark UnruhAlbuquerque, New Mexico

Raymond VanholderGent, Belgium

Anitha VijayanSt. Louis, Missouri

Ron WaldToronto, ON, Canada

Michael WalshHamilton, ON, Canada

Matthew WeirBaltimore, Maryland

Steven WeisbordPittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Jessica WeissPortland, Oregon

Adam Whaley-ConnellColumbia, Missouri

Colin WhiteVancouver, BC, Canada

Mark WilliamsBoston, Massachusetts

Alexander WisemanAurora, Colorado

Jay Wish

Indianapolis, IN

Myles WolfChicago, Illinois

Jerry YeeDetroit, Michigan

Bessie YoungSeattle, Washington

Eric YoungAnn Arbor, Michigan

Carmine ZoccaliReggio Calabria, Italy

CJASNClinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

-

CJASNExecutive DirectorTod Ibrahim

Director of CommunicationsRobert Henkel

Managing EditorShari Leventhal

TheAmerican Society of Nephrology (ASN)marks 50 years of leading the fightagainstkidneydiseasesin2016.Throughouttheyear,ASNwillrecognizekidneyhealthadvances fromthepasthalf centuryand look forward tonewinnovationsin kidney care. Celebrations will culminate at ASN Kidney Week 2016,November 1520, 2016, at McCormick Place in Chicago, IL.

www.cjasn.org

Submit your manuscript online through Manuscript Central at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/cjasn.

Contacting CJASNCorrespondence regarding editorial matters should be addressedto the Editorial Office.

Editorial OfficeClinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology1510 H Street, NW, Suite 800Washington, DC 20005Phone: 202-503-7804; Fax: 202-478-5078E-mail: [email protected]

Contacting ASNCorrespondence concerning business matters should be addressedto the Publishing Office.

Publishing OfficeAmerican Society of Nephrology1510 H Street, NW, Suite 800Washington, DC 20005Phone: 202-640-4660; Fax: 202-637-9793E-mail: [email protected]

Membership QueriesFor information on American Society of Nephrology membership,contact Pamela Gordon at 202-640-4668; E-mail: [email protected]

Subscription ServicesASN Journal Subscriptions1510 H Street NW, Suite 800Washington, DC 20005Phone: 202-557-8360; Fax: 202-403-3615E-mail: [email protected]

Commercial Reprints/ePrintsHope RobinsonSheridan Content ServicesThe Sheridan Press450 Fame AvenueHanover, Pennsylvania 17331Phone: 800-635-7181, ext. 8065Fax: 717-633-8929E-mail: [email protected]

Indexing ServicesThe Journal is indexed by NIH NLMsPubMed MEDLINE; Elseviers Scopus; andThomson Reuters Science Citation IndexExpanded (Web of Science), Journal CitationReports - Science Edition, Research Alert, andCurrent Contents/Clinical Medicine.

Display AdvertisingThe Walchli Tauber Group2225 Old Emmorton Road, Suite 201Bel Air, MD 21015Mobile: 443-252-0571Phone: 443-512-8899 *104E-mail: [email protected]

Classified AdvertisingThe Walchli Tauber Group2225 Old Emmorton Road, Suite 201Bel Air, MD 21015Phone: 443-512-8899 *106E-mail: [email protected]

Change of AddressThe publisher must be notified 60 days in advance. Journalsundeliverable because of incorrect address will be destroyed. Duplicatecopies may be obtained, if available, from the Publisher at the regularprice of a single issue.

DisclaimerThe statements and opinions contained in the articles of TheClinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology are solelythose of the authors and not of the American Society of Nephrologyor the editorial policy of the editors. The appearance ofadvertisements in the Journal is not a warranty, endorsement,or approval of the products or services advertised or of theireffectiveness, quality, or safety. The American Society ofNephrology disclaims responsibility for any injury to persons orproperty resulting from any ideas or products referred to in thearticles or advertisements.

The Editor-in-Chief, Deputy, Associate, and Series Editors, as well as theEditorial Board disclose potential conflicts on an annual basis. Thisinformation is available on the CJASN website at www.cjasn.org.

POSTMASTER: Send changes of address to Customer Service, CJASN Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 1510 H Street, NW, Suite800, Washington, DC 20005. CJASN Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, ISSN 1555-9041 (Online: 1555-905X), is an official journalof the American Society of Nephrology and is published monthly by the American Society of Nephrology. Periodicals postage at Washington, DC, andat additional mailing offices. Subscription rates: domestic individual $438; international individual, $588; domestic institutional, $970; internationalinstitutional, $1120; single copy, $75. To order, call 504-942-0902. Subscription prices subject to change. Annual dues include $33 for journalsubscription. Publications mail agreement No. 40624074. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to PO Box 503 RPO West Beaver Creek RichmondHill ON L4B 4R6. Copyright 2016 by the American Society of Nephrology. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper), effective with January 2006, Vol. 1, No. 1.

-

Role of the Medical Director

Introduction: Role of the Medical Director Series

Robert Provenzano* and Jeffrey L. Hymes

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 325, 2015. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11811214

Nephrology has been a leader in the delivery of high-quality metric- and value-driven care for many years.Some of the reasons for this derive from the uniquehistory and payment system for the care of patientswith ESRD. Early in the ESRDprogram and continuingtoday, the Renal Network System focused on qualityand safety. Simultaneously, the US Centers for Medi-care and Medicaid Services (CMS) and its regulatoryrequirements drove improved outcomes. TheUSRenalData Systemdata set definedobservational benchmarks,and the ability of dialysis organizations to execute pro-cesses focused on improving quality of care, helpedmoveour subspecialty forward.The role of themedicaldirector as a focal point in facility-driven quality carehas been key to this evolution. In our opinion, this hasbeen aunique feature of renalmedicine comparedwithother specialties.

The roles and responsibilities of medical directorshave changed and increased significantly since 1972,whenMedicare entitlementwas extended to thosewithkidney failure, irrespective of age (1). In October 2008,the CMS reissued the Conditions for Coverage (CfC)updating and clarifying the role of themedical directorfor the first time in 30 years (2,3). This update not onlyhelped crystalize the role but expanded its importanceas medicine evolves from a volume- to value-basedsystem. Today, with .600,000 patients under thecare of nephrologists, the role of the medical directorhas become even more critical in the management ofthis complex patient cohort (4).

Medical directors no longer practice in isolation butare integral members of the larger team of renal pro-viders and are empowered by data and tools to driveimproved renal outcomes. In this issue of CJASN, webegin a series on the role of the dialysis facility medicaldirector. This series brings together content and expe-riential experts to provide a broad-based practicalcompendium for all medical directors, both experi-enced as well as novice. This series will serve as a refer-ence and repository of the expertise of our colleagues,many ofwhomhave helped build and shape the field ofnephrology.

In this series, the authors practically interpret theCfC, and add their experience and expertise to betterdefine the role and responsibilities ofmedical directors.In this issue, Drs.Maddux andNissenson,who serve asthe chief medical officers of the two largest dialysisproviders in the United States, provide an overviewof the evolving role of the dialysis facility medical

director. In subsequent issues, experts in patient safetyand quality, water treatment, and infection control willpropel these subjects to the expectations of 21st centuryrenal care. The broader responsibility of a single facilityin an integrated renal care model will also be explored,defining the pivotal role of the medical director inbridging the fragmented, facility, renal clinic or office,and hospital environments in the world of integratedrenal care. Discussions of the vexing problemof dealingwith challenging patients and colleagues, the legal im-plications of being a medical director, and the medicaldirectors relationship to the regional ESRD Networks,will complete the series.In this series, the authors have created aguide to one of

the most important, challenging, and rewarding aspectsof the nephrologists professional career, that of the di-alysis clinicmedical director. This is a critical, expanding,and exciting role. The success of the subspecialty of ne-phrology depends not only on properly executing thebasic blocking and tackling as articulated in this series,but also on rising to the next level of performance re-quired of true leaders in the field of renal medicine.

DisclosuresR.P. is employed by and is a shareholder of DaVita Health-

care Partners and is also a shareholder of Vasc-Alert LLC,Nephroceuticals LLC, and Roo LLC. J.L.H. is chief medicalofficer of Fresenius Medical Services and serves on theRenal Physicians Associations Board of Directors and theNephroceuticals LLC Scientific Advisory Board.

References1. Social Security Administration: Social Security Amendments

of 1972: Public Law 92-603. Fed Regist 75: 13291493,1972

2. US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: 42 CFR494: Conditions for Coveragefor End-Stage Renal Disease Facilities. Fed Regist 73:2047520484, 2008

3. USCenters forMedicare andMedicaid Services: Interpretiveguidance for conditions for coverage. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/downloads/SCletter09-01.pdf.Accessed December 5, 2014

4. US Renal Data System: 2012 Annual Data Report: Atlas ofChronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in theUnited States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health,National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and KidneyDiseases, 2012

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available atwww.cjasn.org.

*DaVita Inc, Detroit,Michigan; andFresenius MedicalCare North America,Nashville, Tennessee

Correspondence:Dr. RobertProvenzano, DaVitaInc, 22201 MorossRoad, Suite 150,Detroit, MI 48236-2100. Email: [email protected]

www.cjasn.org Vol 10 February, 2015 Copyright 2015 by the American Society of Nephrology 325

http://https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/downloads/SCletter09-01.pdfhttp://https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/downloads/SCletter09-01.pdfhttp://https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/downloads/SCletter09-01.pdfhttp://www.cjasn.orgmailto:[email protected]:[email protected]:[email protected]

-

Role of the Medical Director

The Evolving Role of the Medical Director of a DialysisFacility

Franklin W. Maddux* and Allen R. Nissenson

AbstractThe medical director has been a part of the fabric of Medicares ESRD program since entitlement was extendedunder Section 299I of Public Law 92-603, passed on October 30, 1972, and implemented with the Conditionsfor Coverage that set out rules for administration and oversight of the care provided in the dialysis facility. The roleof the medical director has progressively increased over time to effectively extend to the physicians servingin this role both the responsibility and accountability for the performance and reliability related to the careprovided in the dialysis facility. This commentary provides context to the nature and expected competencies andbehaviors of these medical director roles that remain central to the delivery of high-quality, safe, and efficientdelivery of RRT, which has become much more intensive as the dialysis industry has matured.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 326330, 2015. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04920514

History of the Role of the Medical Director inESRD CareThe Medicare program was 7 years old when entitle-ment was extended in 1972 to those with disabilitiesindependent of age. The definition of disabled in-cluded those with CKD who required dialysis or a kid-ney transplant for survivalthey shall be deemeddisabled for purposes of Medicare parts A and B (1).What was thought to be a small, socially redeemingprogram, has grown to .600,000 patients with increas-ingly complex chronic comorbid conditions, and a totalcost of .$40 billion. Currently, 1.3% of all Medicarebeneficiaries are covered under the ESRD Programand consume nearly 8% of all Medicare dollars.

With the implementation of the entitlement in 1973,there was gentle growth in outpatient dialysis facil-ities. These were part of academic institutions or in thecommunity, and had clinical oversight provided bynephrologists, who participated in administration ofthe facility (medical director) as well as providedindividual patient care (attending nephrologist). Asthe program began to grow, it became clear that reg-ulatory oversight by the US Centers for Medicare andMedicaid Services (CMS), then the Health Care Financ-ing Administration (HCFA), needed to be codified.Thus, the initial Conditions for Coverage (CfC) wereissued to govern the operation of dialysis facilities.

The initial CfC mandated that every facility have aphysician as medical director whose responsibilitiesincluded creating, reviewing, and updating facility pol-icies and procedures; ensuring appropriate modalityeducation and selection for all patients; overseeingtraining of staff; and ensuring safe and effective di-alysis treatments. The physician director was to be boardeligible or certified in internal medicine or pediatricsand had to have at least 12 months of experience caringfor patients on dialysis. The same nephrologists were

delivering direct patient care and participating on thegoverning body to ensure that the facility was runningproperly. This proved confusing for some nephrologistswho could not separate the patient care role from theadministrative role as medical director. Some physi-cians seemed to treat the medical directorship as anhonorary position without setting aside specific ad-ministrative time to accomplish the job. Of note, eventhe HCFA had a lack of clarity about the medical di-rector role. When facilities were found deficient duringroutine surveys, the facility (not the medical director)was cited even if the area of deficiency was a directmedical director responsibility.As the dialysis industry consolidated during the

1990s, nephrologists were contracting with dialysiscompanies to provide medical director services. Thiscontractual relationship camewithmore explicit expec-tations of the duties of the medical director and rudi-mentary systems of accountability to monitor deliveryof these duties. In 2002, the US Department of Healthand Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG)issued a report titled Clinical Performance Measuresfor Dialysis Facilities: Lessons Learned by the MajorDialysis Corporations and Implications for Medicare(2). Among a number of recommendations to theCMS in that report to help improve the healthcareoutcomes for dialysis patients was that the CfC berevised so that they require facility medical direc-tors to exert leadership in quality improvement (2).In 2008, a revised CfC was published that spelled outthe responsibilities of the medical director moreclearly and completely, as recommended by the OIGreport in concert with CfC Interpretive Guidelines tofoster correct interpretation of the CfC (3). The medi-cal director is not solely held responsible for everyaspect of care provided in the dialysis facility, but isrecognized in 53 V-Tag segments of the interpretive

*Fresenius MedicalCare North America,Waltham,Massachusetts; andDaVita HealthCarePartners, Denver,Colorado

Correspondence:Dr. Franklin W.Maddux, FreseniusMedical Care NorthAmerica, 920 WinterStreet, Waltham, MA02451-1457. Email:[email protected]

www.cjasn.org Vol 10 February, 2015326 Copyright 2015 by the American Society of Nephrology

-

guidelines to the CfC (4) (Supplemental Table 1). The facilityis still the entity sanctioned by the CMS if a medical directordoes not carry out his or her responsibilities, although di-alysis organizations are developing increasingly specificcontracts that delineate medical director expectations andconsequences for underperformance. Being a medical di-rector is not an entitlement; rather, it is an essential roleto ensure high performance and high reliability in provid-ing care within the dialysis facility.

Evolution of the Delivery System for ESRD CareDialysis facilities were initially developed with a govern-

ing body including the facility administrator or chief/headnurse, a medical director, and an interdisciplinary team.The latter consisted of registered nurses, machine techni-cians, dietitians, and social workers. Before 1990, dialyzerswere commonly reprocessed and few injectable medicationswere administered during dialysis beyond intravenous an-tibiotics. By 1990, as the patient population expanded andtechnical and medication advances were adopted, the sys-tem for delivering care changed when many more patientsbegan dialyzing with reprocessed dialyzers, dialysis equip-ment became more sophisticated with enhanced safetyfeatures, and dialyzers and concentrate solutions obviatedthe severe hypotension seen with earlier-generation thera-pies. In addition, the widespread availability of intravenouserythropoietin, iron, and vitamin D improved anemia andmetabolic bone disease management. With the introduc-tion of erythropoietin and intravenous vitamin D, registerednurses were needed to spendmore time administering med-ications than caring directly for patients, whereas increas-ing responsibility for placing dialysis needles and setting upand tearing down machines was part of the job of the tech-nician. During this time, the dialysis facility administratorswere often not nurses, but business administrators. Thesechanges in the interdisciplinary team along with an in-creasing acuity of patients have made the role of the medicaldirector increasingly one of senior leadership, coach, andhead of the care team and facility medical staff. The medicaldirector role emphasizes enhanced accountability for over-sight of a more complex technical and regulatory environ-ment of the modern dialysis facility.

Perspectives on the Medical Director RoleThe medical director of a dialysis facility incorporates

both clinical knowledge and administrative capabilities inhelping to guide the facility toward high performance andhigh reliability. There are three primary focus areas withregard to this administrative role, including regulatory re-quirements,medical practice standards, and operational over-sight with the dialysis provider business leadership (511).The medical director is not asked to care directly for anygiven patient; rather, the medical director provides popula-tion management and implement processes, methods, andtools for delivering care of the highest quality in a safe andefficient manner.The CfC and associated interpretive guidelines define

areas in which the medical director has distinct responsibilityand accountability for overseeing and leading facility per-formance independent of the ownership or organizational

characteristics of the dialysis facility. These areas of influenceinclude infection control, water and dialysate quality, reuseof dialyzers, physical environment, patient assessment stan-dards, patient plan of care processes, quality assessment andperformance improvement, personnel qualifications, and gov-ernance of the facility.Each of the CfC regulated areas is noted in a distinct no-

menclature known as the V-Tag (a computer-identified tagin interpretive guidelines to the CfC). For example, infec-tion control references the medical director in two V-Tags,in which the medical director participates in defining theinfection control culture and policies and is expected to beresponsive to a surveyor when asked about the infectioncontrol program and reporting mechanisms. Furthermore,there are 16 V-Tags related to water quality. Each of theserecognizes the expectation that the medical director isknowledgeable of the water treatment system installed inorder to be sure that the water quality meets the Associationfor the Advancement ofMedical Instrumentationwater qual-ity standards for dialysis.The physical environment, patient assessment, and plan

of care areas have three to four V-Tags, each of which relateto the medical directors role in ensuring that emergencyequipment and drugs are available and that staff are prop-erly trained. Patient assessment frequencies and contentare regulated by the CfC, including ensuring that each pa-tient has a valid dialysis prescription delivered in a safephysical environment. The quality assessment and per-formance improvement V-Tag recognizes the medical di-rectors role in leading the interdisciplinary team in themeasurement, observation, interpretation, and planningfor quality care process improvement within the dialysisfacility.There are four V-Tags in which the medical director must

provide assessment of clinical and medical staff capabilitywithin the dialysis facility, as well as the disciplines sur-rounding patient care technician (PCT) training. Further-more, support of governing body rules for staffing andemploying technical, PCT, and nursing positions are partof the medical director role. This includes staff education,training and competency assessment of staff, and logisticsof admitting patients to facilities.Finally, the medical director is recognized no less than

seven times in V-Tags related to the governance of dialysisfacilities, having close communication with the governingbody regarding quality assessment and performance im-provement, orientation and communication with the medicalstaff, assurance of compliance to governing body decisions,clear plans for dealing with patient grievances, and decisionmaking on whether any condition with the facility wouldprohibit the ability to deliver safe treatments (12).

A Clearer RoleOriginally, the medical director role was narrow and

focused singularly on the clinical policies and procedures inthe dialysis facility. In the early years after the Medicareentitlement, the dialysis facility medical directorship wasprestigious and an honor. The revision to the CfC in 2008became explicit about the expectations of the work involvedgauged to accommodate 25% of the medical directors totalwork time. This move toward active and engaged executive

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 326330, February, 2015 Evolving Role of the Medical Director, Maddux and Nissenson 327

http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04920514/-/DCSupplemental

-

leadership was a tremendous change in the responsibilityand accountability for medical directors. As the dialysis pro-viders began to consolidate, the medical director became thecentral authority for observing and molding practice pat-terns by the full medical staff in their facility, guided bythe medical leadership of the dialysis provider organization.Such facility practice patterns are dictated by the clinical andmedical needs of the patients, the safe environment of thefacility, and a highly integrated reporting and analysis pro-cess. The role of the medical director has evolved into a keydecision-making component on both the delivery of clinicalservices and operations at the dialysis facility.

Skill SetsDistinctive Roles for Patient Care and AdministrationMost medical directors are also attending physicians

with some number of patients being treated at the dialysisfacility. One of the great distinctions of the medical direc-tor role is that the primary purpose is not the care of anyindividual patient or clinical circumstance; rather, the med-ical directormanages both the administrative and populationmanagement needs of the facility as a whole. The develop-ment of a strong clinical staff and the ability to distinguishindividual patient care decisions as an attending nephrol-ogist and the administrative role as a medical director in thedialysis facility are challenges that each medical directormust master.

A Need for Facility Population Management SkillsAlthough not explicitly stated in the CfC, to fulfill the con-

temporary responsibilities as medical director, the nephrol-ogist is accountable for the health outcomes of a discretepopulation of patients, those who are receiving care withintheir dialysis facility (13). If this is done well, the need foremergency department visits, hospitalizations, and costlyprocedures will be minimized. This concept is not one thatnephrologists fully understand or have been exposed to intraining. Overall facility measurement of outcomes, gener-ally driven by protocols and algorithms, are key to success-ful population management, and robust data and analyticsare necessary to provide the medical director with the in-formation needed to manage the population. This is one ofthe most challenging parts of a medical director role becauseit means working with other physicians in the facility to en-sure adoption of standardized care protocols and organizedsystems of care, always recognizing that the art of medicineis deciding when a protocol should not be followed. Finally,true population management requires the medical directorto work with the interdisciplinary team, attending nephrol-ogists, and patients to engage patients in their own care,which is essential for driving the best outcomes. The needfor discreet population management skills is consistent withthe requirement for medical directors to provide a patient-centered safe environment of quality care as articulated byMedicare in its Quality Strategy Document 2014 (14).

Team LeadershipThe medical director acts as the senior clinical leader in a

dialysis facility and is responsible for both communicatingand listening to the medical staff in determination of thoseclinical policies to which the whole medical staff will adhere.

Beyond this, the medical director retains a responsibilityfor the clinical strength of the interdisciplinary team mem-bers including clinical nursing staff, PCTs, dieticians, socialworkers, and any other ancillary staff that interact with thepatient population. The medical director should include inhis or her purview the operational leadership that has greateffect on the patients experience of care and ultimately qual-ity of life. The close working relationship of this team is fre-quently the critical factor in developing a high-performingand highly reliable dialysis facility. The medical directormust present clear leadership that distinctly sets the toneand culture for all staff that work with patients in the fa-cility and exemplifies the primary goal of delivery of high-quality, safe, and effective RRT.

Business AcumenAn effective medical director is asked to be more capable

of influencing effective operations, culture, staff develop-ment, education, and sustainability of the facility. Medicaldirectors should seek and obtain background in basic businessprinciples so that they can understand how to influence gooddecisions about equipment, standardized processes, andhiring. This knowledge supports the need for developing asustainable, healthy dialysis facility. Although specifics re-garding business competency are not a regulatory require-ment of the CfC, such expertise enhances the effectivenessof the medical director. When a medical director does notparticipate in the business and operational decisions regard-ing the promotion of safe, effective, and efficient care, thefacility will suffer sustainability risk. Therefore, as the seniorclinical leader within an individual dialysis facility, the med-ical director should take an active and engaged role in foster-ing strategies to improve the facility performance regardingclinical quality, operational excellence, and financial viability.

Technical Skills and BackgroundThe medical director should have completed a full, com-

prehensive fellowship in nephrology that includes hands-on care of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients.It is highly desirable for training to include technical as-pects of dialysis in addition to the medical care of dialysispatients. Experience such as setting up dialysis equip-ment, inserting dialysis needles, monitoring treatments,and shadowing biomedical personnel all are invaluableto a prospective medical director. Finally, an understandingof the regulatory environment in which dialysis facilitiesoperate is essential for a medical director because he or sheis responsible for ensuring that all regulatory requirementsare met so that high-quality, safe, and efficient dialysis isdelivered to all patients at all times (15,16).

Managing a Medical StaffOne of the most challenging responsibilities of a medi-

cal director is overseeing the activities of the medical staff,some members of whom may be part of the medical di-rectors nephrology group and others may be part of com-peting groups. All consider themselves equals with themedical director, which can create points of conflict. Thispart of a medical directors role is one of the most chal-lenging, but really involves developing, fostering, andreinforcing a true team mentality among the medical staff

328 Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

-

members independent of the practice relationships repre-sented within an individual facility medical staff (17,18).This effort is most effective when the medical director canget the medical staff to have a shared vision and goal forthe facility, as well as clarity about the distinctive roles ofthe medical director and attending nephrologist. This in-cludes robust, frequent, clear communication, and crea-tion of a culture of mutual trust, respect, and adoption ofevidenced-based care pathways or protocols.

Governing Body LeadershipThe medical director plays an active role in helping to

guide and influence the governing body toward rationalchoices and correct decisions in the development of a high-performing and highly reliable dialysis facility. The med-ical director may be the chief executive officer of the facilityin some cases, whereas the medical director may simply bea member of the governing body in others. This governingbodys role is to recognize both the direct business inter-ests, as well as relationships between the dialysis providerand the clinical care paradigm supported at the facility. Themedical directors role includes ensuring that the governingbody is aware and effectively addresses ongoing qualityimprovement processes that lead to effective evidence-based quality improvements in care at the facility. The gov-erning body meetings should be regular and should haveboth regular routine and topical components to the agendathat include assessment of performance of the facility fromfinancial, operational, and clinical quality standpoints. Thegoverning body must set the tone for development of astrong, highly educated, proficient, and professional staff.The governing body must also adjudicate any conflictsand create a rational observation of the clinical staff abilityto deliver safe and effective therapy. In many cases, themedical director is the most senior person at the governingbody meeting within the organization and should thus takeon a substantial role in providing leadership, direction, andactive participation in governing body decisions.As the Medicare ESRD Program enters its 40th year, now

is a good time to reflect on the role of the medical directoras well as the value that an effective medical director canbring to patients, medical staff members, the interdisci-plinary team, and the organization of which he or she is apart. In the early years of the ESRD entitlement, the medicaldirector worked with the chief nurse to develop and overseepolicies and procedures within the facility. This limited rolewas seen by many nephrologists as largely an entitlementfor thema recognition that they, the doctor, were really incharge and bringing patients to the facility. Although somenephrologists were deeply engaged in other aspects of theadministration of the facility, this remained the exceptionrather than the rule. With the revision of the CfC in 2008,the role of the medical director became much more explicit,with the responsibilities and accountabilities delineated indetail. Although this approach was long overdue, manynephrologists serving as medical directors were not preparedfor this set of responsibilities or for the expected time com-mitment of a quarter of their full-time professional effort.It is now clear that for dialysis patients to receive the safe,

effective, and efficient care they need and deserve, eachfacility must have a fully engaged medical director whounderstands and carries out the responsibilities of the role

as an enthusiastic leader of a highly functioning team. Botha deep understanding of the technical and regulatory as-pects of dialysis delivery as well as an appreciation of theconcept and tools for population management are essential.In addition, strong interpersonal communication skills andthe ability to manage conflict are essential qualities.A careful self-examination will reveal that we have not

taught the essential skills of being a dialysis facility medicaldirector during the nephrology fellowship. Excellent ef-forts have been initiated by the Forum of ESRD Networksand the Renal Physicians Association, but these efforts needbroader dissemination (19,20). In addition, only recentlyhas the American Society of Nephrology attempted to con-duct medical director training courses at its annual meeting.Dialysis organizations have such educational programs spe-cific to their companies, but getting significant participationis a challenge. It is time to come together with industry, aca-demic institutions, and renal organizations to recommendthe best methods to train future medical directors.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank John Larkin and Jackie Wenzler for assisting in the

preparation of this article.

DisclosuresF.W.M. is employed by Fresenius Medical Care and holds stock

in the company. A.R.N. is employed by DaVita Health Care Part-ners and holds stock in the company.

References1. Social Security Amendments of 1972 Section 299I. Available at

http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v36n3/v36n3p3.pdf.Accessed September 19, 2014

2. US Department of Health and Human Services Office of In-spector General: Clinical Performance Measures for DialysisFacilities: Lessons Learned by the Major Dialysis Corporationsand Implications for Medicare, 2002. Available at http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-99-00054.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2014

3. US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: InterpretiveGuidance for Conditions for Coverage, 2008. Available athttp://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/GuidanceforLawsAndRegulations/Downloads/esrdpgmguidance.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2014

4. Fresenius Medical Care North America: CfC MedicalDirector Reference Table. Available at http://fmcna.com/fmcna/idcplg?IdcService5GET_FILE&allowInterrupt51&RevisionSelectionMethod5LatestReleased&Rendition5Primary&dDocName5PDF_3000063951. Accessed July 22,2014.

5. Lacson E Jr, Maddux FW: Intensity of care and better outcomesamong hemodialysis patients: A role for the Medical Director.Semin Dial 25: 299302, 2012

6. Spiegel BM: Treatment center characteristics associated withbetter outcomes: A role for the medical director? Semin Dial 25:296298, 2012

7. Goldman RS, Latos DL: Dialysis medical directors role inmaintaining quality of care and responsibility for facility-specificpatient outcomes: Evolution and current status. Semin Dial 25:286290, 2012

8. DeOreo PB, Wilson R, Wish JB: Can better understanding anduse of treatment center performance feedback improve hemo-dialysis care? A role for themedical director. SeminDial 25: 290293, 2012

9. Maddux FW, Maddux DW, Hakim RM: The role of the medi-cal director: Changing with the times. Semin Dial 21: 5457,2008

10. Kliger AS: The dialysis medical directors role in quality andsafety. Semin Dial 20: 261264, 2007

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 326330, February, 2015 Evolving Role of the Medical Director, Maddux and Nissenson 329

http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v36n3/v36n3p3.pdfhttp://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-99-00054.pdfhttp://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-99-00054.pdfhttp://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/GuidanceforLawsAndRegulations/Downloads/esrdpgmguidance.pdfhttp://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/GuidanceforLawsAndRegulations/Downloads/esrdpgmguidance.pdfhttp://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/GuidanceforLawsAndRegulations/Downloads/esrdpgmguidance.pdfhttp://fmcna.com/fmcna/idcplg?IdcService=GET_FILE%26allowInterrupt=1%26RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased%26Rendition=Primary%26dDocName=PDF_3000063951http://fmcna.com/fmcna/idcplg?IdcService=GET_FILE%26allowInterrupt=1%26RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased%26Rendition=Primary%26dDocName=PDF_3000063951http://fmcna.com/fmcna/idcplg?IdcService=GET_FILE%26allowInterrupt=1%26RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased%26Rendition=Primary%26dDocName=PDF_3000063951http://fmcna.com/fmcna/idcplg?IdcService=GET_FILE%26allowInterrupt=1%26RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased%26Rendition=Primary%26dDocName=PDF_3000063951

-

11. Gutman RA: Medical direction of dialysisa critical leadershiprole. Semin Dial 20: 257260, 2007

12. Lindenfeld S, Vlchek D: Engaging physicians in continuousquality improvement. Adv Ren Replace Ther 8: 120124, 2001

13. Nissenson AR: Should medical directors assume responsibility forfacility-specific outcomes? Semin Dial 25: 284285, 2012

14. Garrick R, Kliger A, Stefanchik B: Patient and facility safety inhemodialysis: Opportunities and strategies to develop a cultureof safety. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 680688, 2012

15. Vaqar S, Murray B, Panesar M: The medical-legal responsibilitiesof a dialysis unit medical director. Semin Dial 27: 472476,2014

16. Wish JB: What is expected of a medical director in the Centersfor Medicare and Medicaid Services Conditions of Coverage?Blood Purif 31: 6165, 2011

17. DeOreo PB: The medical directorship of renal dialysis facilitiesunder the newMedicare conditions for coverage: Challenges andopportunities. Blood Purif 27: 1621, 2009

18. Deoreo PB: How dialysis is paid for: What the dialysis medicaldirector should know, and why. Semin Dial 21: 5862, 2008

19. US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: About theCMS Quality Strategy, 2014. Available at http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/CMS-Quality-Strategy.html. AccessedAugust 10, 2014

20. Forum of ESRD Networks Medical Advisory Council: MedicalDirector Toolkit, 2012. Available at http://esrdnetworks.org/mac-toolkits/download/medical-director-toolkit-2. AccessedSeptember 19, 2014

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04920514/-/DCSupplemental.

330 Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/CMS-Quality-Strategy.htmlhttp://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/CMS-Quality-Strategy.htmlhttp://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/CMS-Quality-Strategy.htmlhttp://esrdnetworks.org/mac-toolkits/download/medical-director-toolkit-2http://esrdnetworks.org/mac-toolkits/download/medical-director-toolkit-2http://www.cjasn.orghttp://www.cjasn.orghttp://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04920514/-/DCSupplementalhttp://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04920514/-/DCSupplementalhttp://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.04920514/-/DCSupplemental

-

Role of the Medical Director

The Medical Director and Quality Requirementsin the Dialysis Facility

Brigitte Schiller*

AbstractFour decades after the successful implementation of the ESRD program currently providing life-saving dialysistherapy to >430,000 patients, the definitions of and demands for a high-quality program have evolved and in-creased at the same time. Through substantial technological advances ESRD care improved, with a predominantfocus on the technical aspects of care and the introduction of medications such as erythropoiesis-stimulatingagents and active vitamin D for anemia and bone disease management. Despite many advances, the size of theprogramand the increasingly older andmultimorbid patient population have contributed to continuing challengesfor providing consistently high-quality care. Medicares Final Rule of the Conditions for Coverage (April 2008)define the medical director of the dialysis center as the leader of the interdisciplinary team and the personultimately accountable for quality, safety, and care provided in the center. Knowledge and active leadershipwith ahands-on approach in the quality assessment and performance improvement process (QAPI) is essential for theachievement of high-quality outcomes in dialysis centers. A collaborative approach between the dialysis providerand medical director is required to optimize outcomes and deliver evidence-based quality care. In 2011 theCenters for Medicare & Medicaid Services introduced a pay-for-performance programthe ESRD quality in-centive program (QIP)with yearly varying qualitymetrics that result in payment reductions in subsequent yearswhen targets are not achieved during the performance period. Successwith theQIP requires a clear understandingof the structure, metrics, and scoring methods. Information on achievement and nonachievement is publiclyavailable, both in facilities (through the facility performance score card) and on public websites (includingMedicares Dialysis Facility Compare). By assuming the leadership role in the quality program of dialysis facilities,themedical director is given an important opportunity to improve patients lives and effect true change in a patientpopulation dealing with a very challenging chronic disease. This article in the series on the role of the medicaldirector summarizes the medical directors specific role in the quality improvement process in the dialysis facilityand the associated requirements and programs, including QAPI and QIP.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 493499, 2015. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05810614

Introduction

Air travel didnt get safer by exhorting pilots toplease not crash. It got safer by designing planesand air travel systems that support pilots and othersto succeed in a very, very complex environment.Wecan do that in healthcare, too.

Donald Berwick on the launch ofthe Partnership for Patients April 12, 2011

It isnot enoughtodoyourbest; youmustknowwhatto do, and then do your best.

W. Edwards Deming

It is self-evident that both healthcare providers and pa-tients want high-quality healthcare. Quality is a funda-mental prerequisite for value in any service area andcertainly is of prime importance inmedicine, where oftenthat most critical issue, life and death, is at stake. How-ever, the common underlying tapestry in medicine iswoven by every individuals personal understandingof what quality care entails. Not surprisingly, thedefinition of quality, including how to measure it,varies widely.

Since the 1973 implementation of universal access todialysis care in the United States, many advances inthe delivery of ESRD care have been implemented.The initial goal of this programto allow rehabilita-tion to a full and active lifehas evolved over theensuing 40-plus years and resulted in a larger thanexpected program that provided dialysis services to.430,000 patients in 2013 (1). What was initially aprimarily home-based therapy became a large indus-try of center-based dialysis care for increasingly olderpatients with multiple comorbidities. Delivering a re-liably beneficial product (i.e., high-quality care) to asmall number of patients with limited evidence-basedmandates required a different set-up, one that reliedheavily on individuals and their good intentions. Asthe program grew, the tasks required to ensure qual-ity assurance and quality control transformed.The role of a medical director before expansion of

Medicare payments for dialysis care mainly involvedbeing the treating physician for most if not all thepatients in a facility and thus primarily practicingmedicine for the individual patient. After passage ofthe amendments to the Social Security Act in 1973, the

*Satellite Healthcare,San Jose, California,and Department ofMedicine, Division ofNephrology, StanfordUniversity, Palo Alto,California

Correspondence:Dr. Brigitte Schiller,300 Santana Row,Suite 300, San Jose,CA 95128. [email protected]

www.cjasn.org Vol 10 March, 2015 Copyright 2015 by the American Society of Nephrology 493

-

medical director became part of a wider care team thatincludes nurses, social workers, and dietitians; this Act alsomandated a medical director for each facility. The govern-ing body in each facility further reinforced the teamapproach set forth by Medicare. The nephrologistmedicaldirector took on a managerial role in the facilities, a rolethat focused on quality outcomes for all patients withESRD.Since the implementation of the Medicare ESRD program,

rules for participation had always been clearly outlined (2).The conditions for coverage (CfC) effective October 2008,however, made the medical director the ultimate authorityresponsible for all aspects of quality care delivered in the fa-cility and markedly increased the scope of responsibilities (3).The tasks can be divided into three categoriesadministrative,medical, and technical oversightaccounting for a mana-gerial position that the Centers for Medicare & MedicaidServices (CMS) estimates to be the equivalent of a quarter-full-time position. The time and responsibility requirementare no small burden for a practicing nephrologist and con-tinue to increase, with ever more challenging clinical situa-tions and quality metrics of increasing complexity.The CfC outlines the duties (Table 1). The primary role of

the medical director with respect to quality is providingleadership for the interdisciplinary team and its role inboth individualized patient care and the quality assess-ment and performance improvement process (QAPI).ESRD care has been paid at a composite rate composed of

dialysis and some laboratory tests since 1983. In 2011,following the passage of the 2008 Medicare Improvementsfor Patients and Providers Act (MIPPA), a bundled pay-ment that includes the dialysis treatment, injectable drugs,and all ESRD-related laboratory tests, was implemented.The Act allowed for the prospect of oral drugs to be in-cluded at a later time. MIPPAmandated the introduction ofthe ESRD quality incentive program (QIP). The intent of theprogram is to promote high-quality care in the outpatientdialysis facilities treating patients with ESRD. This pay-for-performance system is unique in the sense that it worksthrough a reduced payment on the facility level, thus link-ing a portion of the payment directly to facility perfor-mance in specific quality metrics. The specific measuresincluded in the QIP are modified and published annuallyand have increased in number, from initially 3 metrics for2012 to 11 metrics for payment year 2016 (4). This rapidmodification and increase of metrics put additional pres-sure on providers and facilities that have limited time

available to implement the new metrics; these metricshave often been published only at the end of the year pre-ceding the implementation year.Nonetheless, the QIP has contributed to considerable

improvement in the results achieved across the United States,including decreased percentage of catheters in place for .90days and increased fistula penetration. Other metrics raisequestions about their meaningfulness as a true quality mea-sure likely to affect patient survival and quality of life, theprimary goals of high-quality care for patients with ESRD.While the QIP may be regarded primarily as a pay-for-performance measure only for the dialysis provider, it isevident that truly life-changing quality metrics will and in-deed already require the active participation of not only themedical director but all referring physicians under the med-ical directors leadership. Quality measures for the practicingnephrologist may be more tangible in the care of patientswith CKD rather than ESRD, resulting in similar wide-rangingreactions (5). However, no matter how one might think aboutthe incentive program and its quality indicators, the QIP ishere to stay.With participation of all stakeholders, the ESRD commu-

nity has an opportunity to advance ESRD care by workingclosely together.

QAPIThe QAPI is led by the medical director, with an in-

terdisciplinary team composed of, at a minimum, a physician(typically the medical director, who has overall responsibilityfor the QAPI program at each facility), a registered nurse(typically the clinical manager), a Masters-prepared socialworker, and a registered dietitian. This team must haveeffective communications and devote sufficient time and at-tention to produce effective quality assessment and perfor-mance improvement activities which positively influencetheir patients outcomes (3). The interdisciplinary teammeets quarterly or monthly, depending on state law, anddocuments all QAPI meetings, activities, and projects.CfC 494.110 (Condition Quality Assessment and Per-

formance Improvement) reads as outlined in Table 2. Thistable also summarizes the scope and the metrics includedin a standard QAPI program. Surveyors focus on thesemeasures during state surveys.Part of the QAPI program is the continued performance

improvement monitoring and also the expectation for pri-oritization of improvement activities. Over the past few

Table 1. Condition for coverage

494.150 Condition: Responsibilities of the Medical Director

The dialysis facility musthave a Medical Directorto be responsible for thedelivery of patient care andoutcomes in the facility.

The Medical Director is accountableto the governing body for the qualityof medical care provided to patients.

Medical Director responsibilitiesinclude, but are not limited to, thefollowing:(a) Quality assessment andperformance improvementprogram(b) Staff education, training,and performance(c) Policies and procedures

494 Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

-

years, because of a focused effort to emphasize the data-driven, target-centered quality and care delivery model, amindset of achieving the target numbers has become in-creasingly prevalent in the facilities. While a desire to reachall target metrics is commendable, efforts to reach these goalsneed to be tempered with the larger picture in mind. Themedical directors leadership role is important in helpingcenters to prioritize improvement projects and in directingefforts to identify and address systemic issues. It is critical tothe success of the QAPI program that true quality issuesaffecting many patients are differentiated from a deviationdue to single-patient outliers. The focus should be on theentire group of patients, with a strategy of making changesso that most patients get better care, not just the outliers.The intent of quality improvement is not to solve the issue ofthe very sick patient who does not meet the target. The in-dividual patient issue is addressed through direct patientcare. Quality improvement instead concentrates on trends,processes, infrastructure, access, and adherence to care as thecause for not achieving quality outcomes in a group of pa-tients (i.e., patients in a dialysis center).A hemodialysis center with a high percentage of central

venous catheters in place for .90 days thus has two issues.One concerns the outlier (i.e., the individual patientwith a catheter in place). This is a patient issue requiringintervention by the nephrologist and care team to place apermanent access, preferably a fistula. The QAPI processlooks at the cause of this issue. What needs to happen toprevent patients from having a hemodialysis catheter?What needs to be done to achieve permanent access inpatients with a catheter in a timely matter? Is this a patientissue, a referral issue, or an access-to-surgery issue? Dopatients understand the risk associated with a catheter?

The answers to these questions allow the facility to im-plement change accordingly to benefit current and futurepatients receiving care at the center. Thus, the QAPI pro-cess embodies one of the ways where the nephrologist asmedical director moves from a patient care provider roleto a population health management role with responsibilityfor facility patient care and outcome. Some differences inthese roles affecting the nephrologists tasks are outlined inTable 3.Attendance at the QAPI meetings is mandated by the

medical director and is critical for a successful program.Providers have supplied resources and tools, includingQAPI manuals, QAPI training, fishbone (cause-and-effect)templates, and quality specialists, to help implement andmaintain a QAPI culture and successful QAPI programs.While delivering high-quality care is intrinsic to healthcare

providers, the QAPI process is often not intuitive even formany well trained and dedicated professionals. A tendencyto jump to solutions without asking all the right questionshinders successful execution of a quality program. It isevident that the success of the QAPI process depends on aneeds to improveget it done attitude of the whole team.The most common error in the QAPI process is founded on abelief that everything has already been done. Root causeanalysiswhich determines the most fundamental causesof an adverse event/outcome that has already occurred bysystematically assessing the multiple types of possible human,process, organizational, equipment, and other failuresis aprerequisite for quality improvement. Fishbone analysis fa-cilitates this process through its illustrative way of summa-rizing the causes. With a medical director leading the QAPImeeting and selecting and developing, with the interdisci-plinary team, a project to execute, continued improvement

Table 2. 494.110 Condition: quality assessment and performance improvement process definition by conditions for coverage andmetrics

The dialysis facility must develop, implement, maintain, and evaluate an effective, data-driven, quality assessment andperformance improvement program with participation by the professional members of the interdisciplinary team.The program must reflect the complexity of the dialysis facilitys organization and services (including those servicesprovided under arrangement), andmust focus on indicators related to improved health outcomes and the preventionand reduction of medical errors. The dialysis facility must maintain and demonstrate evidence of its qualityimprovement and performance improvement program for review by CMS.

QAPI MetricsHealth outcomes and reduction of medical errors by using indicators or performance measures associated withimproved health outcomes and with the identification and reduction of medical errors.

Adequacy of dialysisNutritional statusMineral metabolism and renal bone diseaseAnemia managementVascular accessMedical injuries and medical errors identificationHemodialyzer reuse program, if the facility reuses hemodialyzersPatient satisfaction and grievancesInfection controlAnalyze and document infections to identify trends, establish baseline information on infection incidenceDevelop recommendations and action plans to minimize infection transmission, promote immunizationTake actions to reduce future incidents

Obtained from reference 3. CMS, Centers for Medicare &Medicaid Services; QAPI, quality assessment and performance improvementprocess.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 493499, March, 2015 Medical Director and QA Improvement, Schiller 495

-

is seen repeatedly. Creative, alternative venues are ex-plored in situations where a sentiment prevailed that ef-forts had been exhausted. This changed approach hasprobably contributed to improvements in many areas ofdialysis care, including adequacy and access. Through con-tinued monitoring and tracking of the performance meas-ures, the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle of quality improvementis set into motion: Set a realistic goal; lay out a plan; executeit; reassess; and, depending on the outcome, modify orimplement the process throughout (6) (Table 4). This ap-proach allows the facility to correct any identified problemsthat threaten the health and safety of patients, as mandatedby the CfC.

QIPIn accordance with section 1881(h) of the MIPPA, added

on July 15, 2008, by section 153(c), CMS implemented theESRD QIP to promote high-quality care by outpatientdialysis facilities treating patients with ESRD starting inJanuary 2012 (7). The QIP is a first-of-its-kind program inMedicare and changes the way CMS reimburses for dial-ysis treatments of patients with ESRD. Payment is linkedto certain performance-quality metrics as pay for perfor-mance in a value-based purchasing program. However,the QIP represents a withholding rather than a reward forperformance payment incentive. Facilities who do notmeet certain performance standards are subject to a pay-ment reduction (withholding) of up to 2% in subsequentyears, also known as payment years. An overall facilityscore for applicable measures will determine whether pay-ment should decrease. The scores are publicly reported on

Dialysis Facility Compare (8) and also in the PerformanceScore Certificate. CMS provides this certificate annually toall centers, both those with perfect scores and those withscores resulting in payment reductions. The certificatemust be displayed in the facility for easy review by staffand patients.It is obvious that a proactive involvement of the medical

director is key to achieving the QIP targets. A successfulmedical director must fully understand the QIP, the un-derlying metrics, and its scoring system. The ongoingmonitoring of target metrics, the reinforcement of staff andphysician behavior working toward this goal, and patientengagement and education are essential. The award ofcertificates for perfect performance relies heavily on strongcollaborative efforts between the medical director and thedialysis provider. In a world where consumers use theInternet and social media for product and service choices, itis easy to imagine that patients choice for their dialysistherapy will be guided by such public ratings. And wewould not expect our patients to accept a lower qualityrating when trusting their lives to our care.While the format of the program does not change, the

quality metrics, standards, and weighting of the results andformulas are subject to annual changes. Thus, the initialQIP, performance year of 2010 and payment year in 2012,consisted of 3 metrics, while the current QIP, based on 2014performance for 2016 payment, encompasses 11. The mea-sures initially comprised only clinical metrics, starting withanemia and adequacymeasures. Since then a variation has beenimplemented with clinical metrics, commonly accountingfor 75%90% of the overall score, and reporting measures,representing 10%25% of the overall score. The measures

Table 3. Nephrologists tasks in patient care versus role as medical director in population health management in the dialysis center

Domain Patient Care Population Health Management

Anemiamanagement

Assess patient for clinical causes of anemiaor hemoglobin . 12g/dl

Review, monitor and analyze target levelsfor hemoglobin . 12 g/dl reached in afacility

Safety/clinical issue requiring intervention? Protocol issue?Adherence to policy and procedure?Staff knowledgeeducation need?Safety issue?

Infectioncontrol

Treat patient with antibiotic according toclinical presentation and microbiologyfindings

Review, monitor, and analyzeinfection rate in dialysis center

CVC requiring permanent access? Perform route cause analysisEvaluate cause for infection and possibleintervention to prevent recurrence

Infection surveillanceInfection control policy and procedureStaff/patient and referring physiciansadherence to infection control policyand procedure?

In-service required?

Patient planof care

Individual patient assessments and planof care according to patients individualneeds documented for each patient atmandated intervals

Review referring physicians compliancewith patient care plan documentation,monthly visits and quarterly in-center visits

Reach out to physicians who are out ofcompliance

CVC, central venous catheter.

496 Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

-

have evolved from laboratory results and vascular accessdistribution to more complex clinical events, such as infec-tions reported via the National Healthcare SurveillanceNetwork (9) and patient experiences captured throughthe In-Center Hemodialysis Consumer Assessment ofHealthcare Providers and Systems (10).The actual details of the program are complex, with several

program-years potentially affecting the QIP: a payment year,the comparison period, and the performance period. Thecomparison period is the designated time (often a full year)during which CMS is gathering data on all dialysis facilities.The performance year follows the comparison period andrequires the facility to perform at least as well as during thecomparison period to avoid payment cuts. CMS assesses thefacilitys performance on the basis of the comparison periodand calculates a score for each measure, according to themethods detailed each year in a final rule published in theFederal Register. These changes clearly indicate CMSs effortsto align ESRD care outcomes with the desired triple aim ofhealthcare initiatives to achieve improved patient outcomesand experience of care while containing costs (11).Examples are given for the payment year of 2015 and 2016

based on the measures achieved in the performance period in2013 and 2014, currently ongoing (Table 5). The table illus-trates the complexities of controlling the details of this an-nually changing program. The frequent QIP changes andtime frames may evoke experiences of the Ghosts of Christ-mases Past, Present, and Yet to Come from Charles DickensA Christmas Carol. Not only is everyone required to considerand execute best practices in the present, but performancesof the past and future represent continuous challenges, even-tually painting the longitudinal picture of quality achieve-ment of each facility.

However, one has to applaud some of the resultsemerging since the introduction of the QIP with improve-ments in some important areas, such as vascular access,results once thought by many to be unachievable in theUnited States. Thus, Medicare has introduced a transparentprogram suitable for tracking and positively affectingquality improvements in some domains while maintaininghigh marks in others, such as adequacy (12).As nephrologists and other stakeholders discuss the

ultimate definition of goals for high-quality kidney care,expressing support for many metrics and questioning othersas to their importance in improving patients lives, the focuson more clinical measures guided by clinicians is a goodstep forward. Advancing quality care to improve patient sur-vival, reduce hospitalizations, and improve our patientsexperience with their care are unanimously agreed-upongoals.Kidney Care Partners, a coalition of patient advocates,

dialysis professionals, care providers, andmanufacturers, hascollaborated since its foundation in 2003 to improve qualityof care for patients with CKD. The Kidney Care PartnersStrategic Blueprint for Advancing Kidney Care Quality,released in March 2014, outlines the essential areas for im-provements and touches on wide-reaching domains rangingfrom care coordination and disease management to patientengagement, education, and infrastructure changes (13). Thiswill be a roadmap for many coming years, with great poten-tial to affect the way we deliver dialysis care at a time whenthe discussion about quality care has been reframed (14).Nephrologists are taking the lead in promoting and imple-menting innovative models of care addressing the primaryconcerns in ESRD care, including fluid control, longer dial-ysis times, incorporation of underlying comorbid conditions

Table 4. Plan-do-study-act: quality improvement cycle

Project Phases Steps

Goal: Define a specific, measurable andachievable goal

Decide what you want to changeSet a percentage or absolute change targetEstablish a timeline for completionBetter to start small than to over-reach

Plan What will you do?Who will do it?When will it be done?What are the expectations?What data will be collected?

Do Carry out the planDocument observationsCollect the data

Study Analyze the dataDid the process work?Was it enough?Was the objective met?Is the new process realistic?Are the resources available to implement this new process?

Act Process worked:Implement the planProcess did not work:Revise the plan or start over with a new plan

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 493499, March, 2015 Medical Director and QA Improvement, Schiller 497

-

into the dialysis prescription, infection control, coordinatedcare approaches, increased penetration of home dialysis, andbetter education for our patients (1517).These are truly exciting times for nephrologistsand an

opportunity for medical directors to show and live trueleadership.

Conclusion (Tip of the Month for Medical Directors)It cannot be overstated how this is a time of opportunity

for all clinicians, medical directors especially, to wield theirclinical expertise, intuition, and aspiration to live the coremission of being a physician to affect patients lives bypreventing further adverse events, alleviating suffering,and delivering truly patient-centered care.

Responsibilities and tasks for the medical director of adialysis center have increased both in number and com-plexity over the past few years. A leadership position is aprivilege requiring hard work and dedication. The stressesof daily routine, the increasing requirement for documen-tation with ever-changing demands, pay-for-performanceprograms, and the looming beginnings of healthcare re-form may often mitigate the initial motivation to choosethis profession.However, the leadership role of the medical director in a

dialysis center opens an incredible opportunity to improvenot only individual patient care but also the experience of allpatients cared for in a center. Using intuition and the appli-cation of knowledge and guidance to all staff and patients,the medical director makes a difference in patients lives not

Table 5. Quality improvement program for 2015 and 2016

Payment year 2015 2016

Measure 6 clinical 8 clinicalHb . 12 g/dl Hb . 12 g/dlVAT measure topic VAT measure topicCatheter CatheterFistula FistulaKt/V Kt/VHD HDPD PDPediatric Pediatric

4 reporting NHSN bloodstream infections in HDoutpatients

NHSN HypercalcemiaICH CAHPS 3 reportingMineral metabolism ICH CAHPSAnemia management Mineral metabolism

Anemia management

Performance period CY 2013 CY 2014

Comparison period CY 2011 (achievement) CY 2012 (achievement)CY 2012 (improvement) CY 2013 (improvement)

No improvement scoring for NHSNbloodstream infections

Performancestandard

Nationalperformancerate(CY2011) National performance rate (CY 2012)National performance rate (MayDecember2012) for hypercalcemia

National performance rate (CY 2014) forNHSN

Weighting Clinical 75%, reporting 25% Clinical 75%, reporting 25%, hypercalcemia attwo thirds of each remaining clinicalmeasure

Maximumperformance score

100 points 100 points

Minimum totalperformance score

60 points 54 points

Payment reductionscale

0.5%2%with a 0.5% reduction for every 10 points under theminimum total performancescore

Adapted from Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ESRD quality improvement project summary for payment year 20122016."Clinical"means that target value needs to be achieved. "Reporting" indicates that no target valuewas available and creditwas given forreporting results only. Hb, hemoglobin; VAT, vascular access type; HD, hemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; NHSN, NationalHealthcare System Network (reporting of dialysis-related infection events); ICH CAHPS, In-Center Hemodialysis Consumer As-sessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems; CY, Calendar Year.

498 Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology

-

through direct patient care but through population healthmanagement for all patients at the center.One might argue that the medical director sets the tone

and culture of a dialysis center as the leader who willdetermine whether quality improvement processes are anintegral part of caring for patients or yet another task tocheck off on an overwhelming list of things to do.When compassion and love are ingredients of the quality

programor any aspect of healthcarethey may prove notjust to require more time and energy. They may also in re-turn give back and both fill the buckets of those who rely onus and miraculously add quality to the physicians life aswell (18).

DisclosuresB.S. is a salaried employee of Satellite Healthcare, Inc.

References1. US Renal Data Systems:USRDS Annual Data Report: Atlas of End-

Stage Renal Disease in the United States 2013. Available at http://www.usrds.org/2013/pdf/v2_ch1_13.pdf. Accessed June 7,2014

2. Federal Register, Vol 41, No 108, Thursday June 3, 1976, pp.2250222522

3. Department of Health and Human Services: Centers for Medi-care & Medicaid Services: 42 CFR Parts 405, 410, 413 et al.Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Conditions for Coverage forEnd-Stage Renal Disease Facilities; Final Rule. Fed Regis 73:203702-484, 2008 Available at http://www.cms.gov/CFCsAndCoPs/downloads/ESRDfinalrule0415.pdf. AccessedMay 26, 2014