Co-producedwith the Black Film Institute of the University...

Transcript of Co-producedwith the Black Film Institute of the University...

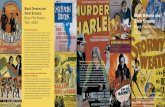

the vision.the voice.

From LA to London and Martinique to Mali. We bring you theworld ofBlack film.

Ifyou're concerned about Black images in commercial film and television, you already know that Hollywood does not reflect the multi-cultural nature 'ofcontemporary society. You know that when Blacks

are not absent they are confined to predictable, one-dimensional roles.You may argue that movies and television shape our reality or that theysimply reflect that reality. In any case, no one can deny the need to take

a closer look at what is COIning out of this powerful medium.

Black Film Review is the forum you've been looking for. Four times ayear, we bring you film criticiSIn froIn a Black perspective. We look

behind the surface and challenge ordinary assurnptiorls about the Blackimage. We feature actors all.d actresses th t go agaul.st the graill., all.d we

fill you Ul. Oll. the rich history of Blacks Ul. Arnericall. filrnrnakul.g - ahistory that goes back to 19101

And, Black Film Review is the only magazine that brings you news,reviews and in-deptll interviews frOtn tlle tnost vibrant tnovetnent in

contelllporary film. You know about Spike Lee but wIlat about EuzIlanPalcy or lsaacJulien? Souletnayne Cisse or CIl.arles Burnette? Tllrougllout tIle African cliaspora, Black fi1rnInakers are giving us alternatives totlle static itnages tIlat are proeluceel in Hollywood anel giving birtll to a

wIlole new cinetna...be tIlere!

VDL.G NO.2

2 2 E e Street, NWas ing on, DC 20006

2 2 466-2753

oacquie Jones

istant EditorsD. Kamili AndersonPeter J. Harris

Consulting EditorTony Gittens( lack Film Institute)

sociate Editor/Film CriticArthu r Johnson

sociate EditorsPat AufderheideRoy Campanella, IIVictoria M. MarshallMark A. ReidMi riam RosenSaundra SharpClyde Taylor

Art Director/Graphic DesignerDavie Smith

Advertising DirectorSheila Reid

Editorial InternsNicole DickensKayhan Parsi

Founding EditorDavid Nicholson1985 - 1989

Black Film Ravie (ISSN 0887-5723) is publishedfour times a year by Sojourner Productions, Inc., anon-profit corporation organized and incorporatedin the District of Columbia. This issue is co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the Universityof the District of Columbia. Subscriptions are $12per year for individuals, $24 peryearfor institutions.Add $10 per year for overseas subscriptions. Subscription requests ,and correspondence should besent to P.O. Box 18665, Washington, D.C. 20036.Send all other correspondence and submissions tothe above address; submissions must include astamped, self-addressed envelope. No part of thispublication may be reproduced without writtenconsent of the publisher. Logo and contents copyright (c) Sojourner Productions, Inc., 1990, and inthe name of individual contributors.

Black Film Review welcomes submissions fromwriters, but we prefer that you first query.with aletter. All unsolicited manuscripts must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed ~nvelope. Weare not responsible for unsolicited "manuscripts.Black Film Review has signed a code of practiceswith the National Writers Union, 13 Astor Place, 7thFloor, New York, N.Y. 10003.

This issue of Black Film Review was produced withthe assistance of grants from the D.C. Commissionon the Arts and Humaniti.es, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the John D. and Catherine T.MacArthur Foundation.

Interview:- - - - - - - - - - - - --- - - - - - - 4by Pat AufderheideMalian filmmaker Cheikh Oumar Sissoko discusses his latest film, Finzan, aselfconscious experiment in storytelling

MO· BETTER BLUESThe Music 6

by Eugene Holley, Jr.TheMan------------------- 8by Lett ProctorTheMovie 12by Kalamu ya Salaam

How to Make Trouble - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 14by Jacquie JonesThe recent Canadian release, How to Make Love to aNegro Without Getting Tired,has stirred up some trouble in the US-but for the wrong reasons

What's New in the Cinema of Senegal _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 16by Francoise PfaffFilmmakers Mousa Bathily and Cheikh Ngaido Bah discuss their latest projects andmovie-making in Senegal today

FEATURESThe Market: - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 24Shopping for Imagesby Victoria MarshallThe American Film Market

Books: -------------------- 26No Identity Crisisby John WilliamsMelvin and Mario Van Peebles' new making-of-the-film book

Film Clips: ------------------- 2PBS Goes to Sundance, Gunn Tribute at the Whitney, and more

Reviews:_ - - - - ~ - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 20Def by Temptation, Bal Poussiere and Without You I'm Nothing

Calendar _ _ _ 32

Classifieds - - - 33

HOW TO MAKETROUBLE

,14

PBS GOES TOSUNDANCEby Ellen Hoffman

The majestic snowdusted Rockies and rusticcabins, screening roomand rehearsal hall of theSundance Institute in Utahprovided a serene settingfor an animated, provocative conference of 100minority women in themedia in May.

It was designed to bringwomen of color who arepracticing filmmakers intocontact with leadingproducers, directors andwriters, both to discussprofessional issues and toencourage connections thatcould result in funding,production and distributionof their films.

For two-and-a-half days,invited participants attended panel discussionsand presentations, a "walkabout" networking session,and screenings and discussions with women of colorabout the films they haveproduced.

Euzhan Palcy, director ofA Dry White Season, andSuzanne DePasse, president of Motown Productions, confronted the issueof how much afilmmakermust compromise in orderto attain success in Hollywood. Palcy recounted thefight-which she ultimatelywon-to make "A DryWhite Season" the story ofa Black family as well asthat of awhite one.

DePasse suggested that"a hot script is the way tobreak into Hollywood." Sheadded that "right now, ithappens (that Hollywood islooking for) white male

2

F i I m

action pictures." DePassegarnered a burst of applause when she asserted:"Some day a Black is goingto write a mainstreamwhite commercial picture."

Another major discussion theme was thedefinition of such "multicultural programming" andthe challenge of deliveringit to the public televisionaudience. Jennifer Lawson,executive vice president forNational Programming andPromotion Services at PBS,defined multi-culturalprogramming as by andabout ethnic, racial andregional groups, but gearedto a general audience forthe prime time schedule.

Mercedes de Uriarte, anassistant professor ofjournalism at the Universityof Texas, warned against a"vegetable soup" approachto programming, one thatwould dilute representationof each ethnic or racialgroup's uniqueness. Shecited statistics showingthat 76.5 percent oftelevision news directorsare white males; 15.6percent white females; 5percent black males; 3percent Hispanic males;1.3 percent black femalesand 1 percent Latinas. Shesuggested that placingmore people of color insuch decision-makingpositions is a condition ofachieving more truly multicultural programming.

In other conference

eli p s•••••

sessions, participantsalluded to the difficulty ofconvincing white televisiondecision-makers to airprograms about minorityfigures or issues. Oneconference participantreported the difficulty ofconvincing white televisiondecision-makers that MilesDavis was an appropriatesubject for a televisionshow.

"When minority producers have to deal withproducers and executiveswho are non-minority, theburden is put on us toconvince (them) that thispart of our culture is valid,"observed Gail Christian, independent producer,former PBS official andconference co-director. Toillustrate, she suggested.turning the tables, imagining a situation in which thedecision-makers were allBlack and a whitefilmmaker "came in with aprogram on Pavarotti andwe all said: 'Who'sPavarotti?' challengingthe producer todefend theproposal.

To facilitatenetworkingbetween thefilmmakers andthe decisionmakers, the pro-

JennfferLawson, executive vice president, National Programming andPromotion Services PublicBroadcasting Service

gram included an afternoon-long "walkabout," inwhich participants wereable to schedule brief appointments to discuss proposals for funding, production and distribution opportunities for their projectswith representatives ofPBS, some Hollywoodstudios, foundations andthe British BroadcastingCorp.

The screening scheduleincluded "Family Gathering," Lise Yasui's attemptto understand her Japanese relatives' internmentin camps in the U.S. duringWorld War II; Jude PaulineEberhard's "Break ofDawn," about a Spanishlanguage radio and recording star who protests theanti-Mexican policies of theU.S. government duringthe Depression; and JulieDash's forthcoming"Daughters of the Dust."Question-and-answersessions with producersfollowed.

Yvonne Smith's "AdamClayton Powell," anepisode in PBS's series,"The American Experience," provoked

the most spirited discus- his play, the Forbidden novel, and collaborated maybe two, African Ameri-sion, including criticism City, starring Gloria Foster. with the late Kathleen can producers. Thesefrom viewers who felt that Gunn died last year of en- Collins on Losing Ground, become their 'in-house'the film did not focus cephalitis. in which he starred, and minorities. They proudlyenough on the role of Curated by author Women, Sisters and showcase the one Africanracism in contributing to Ishmael Reed, the pub- Friends. (See Black Film American in residence andthe late congressman's lisher of Gunn's second Review: Vol 5, No.2) expect to be congratulated.downfall. novel, Rhinestone Share- -John Williams There are far too many

The screenings also cropping (1981), and his NAACP BLASTS imaginative producersafforded the opportunity to award-winning play, Black available for the studios. todiscuss technical issues Picture Show (1975), the STUDIOS FOR limit the numbers theysuch as the use of anima- tribute was a once-in-a- "TOK8IISM" hire."tion and video techniques lifetime event reuniting Disney was the onlyand musical scores. friends and admirers of Sandra Evers-Manly, studio the report acknowl-

Although much of the Gunn's work who flew in president of the Beverly edges as having "activelyconference discussion from every major city in the Hills/Hollywood branch of searched" for more Africanaddressed frustrating and country. the NAACP, has authored a Americans in areas inemotional issues that face Among the films and report analyzing studio which we have traditionallyminority women in the videos showcased on the hiring practices. Contrary been under-represented.media, the main message program was Ganja and to recent articles in the Disney has launched athat emerged was probably Hess, Gunn's surrealistic New York Times that minority writers program.best put by Latina tour-de-force horror which present a highly favorable Evers-Manly is planningfilmmaker Sylvia Morales, he starred in, wrote, and picture of the picture of to release a final report inwho told an interviewer: "A directed; his "soap opera," Blacks in Hollywood, the September, in which eachlot of women of color dwell Personal Problems Vol. I NAACP report reveals that studio will receive atoo much on the difficul- and II (1980-1982), which there are actually fewer job "grade" based on its hiringties. (But the difficulties) used cinema verite tech- opportunities today for practices.are a given." Her advice to . nique to depict the fluctuat- Blacks than there were aher colleagues? "Whatever ing values of a Black urban decade ago. CHARLESyou want to do-write or working-class family; and "Ten years ago at least BURNETT'Sproduce-just do it!," even the belated premiere of there were a few Africanif it means volunteering to Stop! (1970), Gunn's X- American executives," the "AMERICA BE-work on a project free. rated, sex-death thriller report states. "Ten years COMING" FOR PBS"Have a plan, and then made for Warner Brothers ago at least there werehave a Plan B in case Plan which marked his Holly- producers and production Award-winningA doesn't work out. If you wood directorial debut. A companies that were a filmmaker Charles Burnettdon't have stamina, don't lurid, mystery-suspense- viable part of the system." is currently in post-get into this business." drama a la Bergman, the The brief report mentions production on a documen-

The conference was film was a pioneer Black- the "invisible ceiling" that tary special for PBS,sponsored by the Public Hispanic coproduction shot exists in the studio struc- entitled America Becoming.Broadcasting Service. in Puerto Rico. ture that prevents African The project originated with- Ellen Hoffman is a free- Gunn's career hit a high Americans and other its producer, Daisil Kim-Gi-lance writer who lives in point in 1970 when Hal people of color from bson, who raised produc-Washington, DC. Ashby hired him to write reaching top management tion financing from the

the screenplay for The and important creative Ford Foundation. AmericaWHIDIY TRIBUTE Landlord (United Artists), positions. Evers-Manly, Becoming explores our

FOR GUI\I\I produced by Norman who has been negotiating increasingly pluralisticJewison. The film estab- with studio executives for society and the matrix of

Bill Gunn, the late Black lished his talent as a improved hiring practices ethnic interactions in sixpioneer actor-director- screenwriter. Gunn's since March, states in the cities including Miami,scenarist-author-p lay- screenplays include Fame report: "...our meetings Chicago and Houston.wright, was honored at the (Columbia) and The Angel and investigations have Burnett's latest feature film,Whitney Museum of Levine (United Artists). also highlighted the trend To Sleep With Anger,American Art in June the Gunn also penned All the towards 'tokenism.' Stu- starring Danny Glover, willday before the opening of Rest Have Died, his first dios have signed one, be released this fall. _

3

Cheikh Oumar Si

"[FINZAN] DEALS WITH EXCISION AS AN OPPRESSIVE

PRACTICE, BUT I WOULDN'T WANT IT TO BE KNOWN AS A FILM

ABOUT EXCISION. I MADE IT GENERALLY AS A FILM ABOUT

WOMEN'S RIGHTS AND STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM."

by Pat Aufderheide

M"alian film director CheikhOumar Sissoko, whose

second feature film Finzan debutedin the U.S. simultaneously at theSan Francisco Film Festival and atFilmfest D.C~ in Washington, D.C.,boldly terms hinlself a politicallyengaged 'filmmaker. His workscombine a search for popular formwith a goal of raising debate oncritical social issues. \

In Finzan, a moral narrative withtragic overtones is laced withslapstick comedy that draws fromfolk theater. It is a tale that Sissokointended to entertain as well asteach. The story focuses on thetrials of two women: Nanyuma, arecent widow, and her citifiedniece, Fili, who has never undergone the traditional clitoridectomy.

Her cruel husband's deathliberates Nanyuma, but all toosoon the village chief approves apolygamous marriage with her husband's buffoonish and idioticbrother, Bala. Nanyuma, in lovewith a handsome single man whovhad begged the chief for her handwithout avail at her first marriage,fights the arrangement. She goesinto hiding in her brother-in-Iaw'svillage; her.niece Fili supports herbut her brother-in-law tells her shemust marry his other brother, Bala.

Meanwhile, the village receives avisit from a government representative who orders them todeliver tons of millet at alow, fIXed price for government storage. The villagers join together to resist,led by the chief. (Heforces the French-speaking official to negotiatewith him in Bambara, in a

comic standoff.) One woman tellsthe official, 'We're tired of killingourselves for the likes ofyou."

N anyuma is recaptured, transported to her dead husband's village, and dragged through a civil"wedding. Her son organizes a raucous campaign of humiliationagainst Bala by lacing his waterwith an herb that gives him diarrhea and flatulence and by intimidating Bala with imitations ofspirits; the gambits buy Nanyumatime on her wedding night.

The villagers then march on thelocal police station to free thechief. This experience emboldensthe women to ask what the villagerswill do about the plight ofNanyuma, threatening not to sleepwith their husbands until it isresolved.

But not all organizing by womengoes in a progressive direction.

Fili returns with Nanyuma, on herfather's orders, to the village. Butthere she creates a scandal becauseshe has never been excised.Women, backed by the stern chief,excise her by force and she is takenaway bleeding by her father.

N anyuma and her son finallymanage to leave the village uncontested, with her son quite possibilyto find a better life. She leaves behind a village that has tasted thesuccess of community organizingand that has gone through apainful awakening to the questions

about women's rights facing theentire community.

Ultimately Finzan is not the storyof Nanyuma but of the social crisisprecipitated by Nanyuma's (andFili's) resistance to tradition.

The drama is not intimate andpsychological, but social. Thecamera's focus is typically on thesmall group--with plenty of roomfor side and background actionrather than on an individual. Editing is minimalist and cameraworkis often static as if the director,through the camera, were introducing us to an exemplary scenerather than attempting to erase thepsychological distance betweenspectator and character.

T he social crisis is an opensubject for debate, rather than

one that emerges through isolatedpersonal decision. Thus, charactersopenly denounce or proclaimtheir views. A woman says, "Arewomen human beings or slaves?"and the chief says, "Excision is atthe very base of our tradition!"That debate is reinforced by thesoap opera plot twists, and byuninflected touches such as theconstant sight ofwomen at work inthe background of the centralstory.

Finzan is a self-conscious experiment in filmic storytelling on controversial social issues. It offersjokes and buffoonery targeted atthe culpable, and it also delivers

with methodical andpainstaking clarity, itsmessage ofwomen'srights.

Political involvementis in Sissoko's familyhistory; one of hismother's brothers was afamous anticolonial

4

activist who went on to support apan-West African federation andwas eventually jailed after a Western-inspired coup d'etat in 1968.Sissoko, born in 1945, received hishigher education in Paris, havingattended both the Ecole des Hautes Etudes-Sciences Sociales andthe French national film school.He returned to work in Mali,where he has worked as the headof a Malian government agencyproducing documentaries andnewsreels. He recently helpedfound a small filmmakers' cooperative, KORA films.

Sissoko belongs to the Mandingo culture, which encompassesBambara,. Dogon and othercultures. Finwn was made aboutBambara culture in the Bambaralanguage, the dominant languageof Mali.

Pat Aufderheide spoke withSissoko in Washington, D.C.,where he attended packed screenings of his latest film for FilmfestD.C. Translator Pat Belcher kindlyassisted in the conversation.

Black Film Review: Finzan, likeyour earlier work, raises controversial issues.

Cheikh Oumar Sissoko: Yes,Finzan forms part of a series offilms I have made about socialissues in Mali and Mrica. The first,ofwhich I am very proud, is a 35minute documentary called RuralExodus, about the tragedy of thepeasant during the drought. It wasmade in 1984 during the severeSahel drought. The second isNyamanton (Garbage Boys), aboutthe tragedy of children. And nowFinzan is about women.

It deals with excision as anoppressive practice, but I wouldn'twant it to be known as a film aboutexcision. I made it generally as afIlm about women's rights andstruggle for freedom. I wanted toshow that their need for emancipation was necessary for social progress, that it was a struggle both formen and women.

BFR: What does the title mean?Sissoko: "Finzan" is a Bambara

term for a dance performed bymen who have done exceptionaldeeds; I have extended the term towomen struggling for their freedom. As a French title announcesat the beginning of the fum,women do two-thirds of the world'swork, get a tenth of the reward andown only 1 percent of the property.

.BFR: How were you able to makethe film?

Sissoko: It cost $350,000, and wasfunded in several ways. SomeMalian private investors put inmoney, and the government provided in-kind contributions withtechnicians and material. TheGerman 1V channel, ZDF, also putin some money, as did the FrenchMinistry of Cooperation. Finally,we managed a pre-sale to an Italianeducational firm.

There are no professional actorsin the film, but some semi-professional-nobody works full-time asan actor in Mali. I drew somecilent from the national theatercompany. The woman who playsNanyuma played the mother inGarbage BoyS; this is her third fum.And the village chief has been insix or eight films; he played theking in Yeelen.

BFR: Did you have any difficultiesin getting your film approved in M~Ii?

Sissoko: I had to submit the filmboth in script form and in fmalform to Malian government censorship. This is true throughoutMrica; there is no liberty of expression. But I didn't have any realtrouble. With Garbage Boys I didn'tsend them the real script the firsttime, and that caused problems.But this time I submitted the scriptwe used. They approved it, too.

In final form, they asked forsome small changes, which I didn'taccept. For instance, they wantedme to cut the part about the administration demanding millet at afIXed price. I argued that therealready was a public debate aboutthe policy and that my fumwouldn't raise issues that weren'talready in the air. Finally they

accepted my argument.

BFR: Why did you decide to focuson women's rights?

Sissoko: When I was studying inParis in the '70s, the women'srights movement was very largeand made an impression on me.But I think this is very much anissue that belongs to the wholeworld. The Third World has itsspecific problems; women are evenmore exploited than they are inindustrialized countries. Somepeople say that women's rights is aFirst World luxury, but they are theconservatives who want to maintainthe status quo.

I certainly wasn't the first personto raise these issues ofwomen'srights in West Mrica. There havebeen conferences and discussionsby sociologists, historians andmany other people. So the issuesweren't unfamiliar.

Still, no one expected to see afilm on the subject, especially[one] touching on excision. It'sone thing to have a conferenceamong intellectuals and it's another to make a movie about it.

BFR: There are very funny moments in the film and moments oflow, scatalogical humor.

Sissoko: This is all part of a tradition of popular village theatercalled Koteba. It's raucous and canbe satiric. It's performed for free invillage squares, and it's a forum foryoung people to raise socialproblems. It's a very old Bambaratradition. The part where the twokids play tricks on Bala comes .directly from there, as does thecharacter of Bala himself.

BFR: You've combined severalstyles, it seems to me; the film hastragic as well as comic elements andalso a didactic element.

Sissoko: I tried this in GarbageBoys, too. It's a reflection of mychoice to lure people into thetheater in order to hear my message. I also base my decisions on afidelity to our oral traditions.

I'm interested in people coming

continued on page 30

5

Mo' Better Blues

pike Lee's fourth feature film,

Mo' Better Blues, starring Academy award-winner Den

zel Washington, explores the complex, competitive

and colorful world ofjazz musicians. Unlike other

jazz movies of recent years (Round Midnight, Bird, Let's

Get Lost), Mo' Better stays away from the "Hollywood"

version of the jazz musician: a lonely, tortured, drug

crazed artist who spends his life playing to an unap

preciative audience in a dingy nightclub. Instead, the

movie presents the African American improvising

artist as a multi-faceted craftsman.

As Lee explained during a recent press confer

ence, "I felt that we should do a contemporary look at

jazz. What we ~ed to do was show a jazz musician

[who] wasn't ajunkie or an alcoholic but was an

adult. Ifyou look at Round Midnight, the guy (played

by the late saxophonist Dexter Gordon) was like a

little child."

Set in New York, Mo' Better is the story of Bleek Gil

liam (Denzel Washington), a brilliant trumpeter

whose passion for his music cuts him off from almost

everyone around him-most notably, his band mem

bers and the two women who love him: Indigo (Joie

Lee), a schoolteac11er, and Clarke Betancourt (Cynda

Williams), an aspiring singer. Ironically, the one per

son Bleek isn't cut off from is his life-long friend but

incompetent manager, Giant (Spike Lee), who ulti

mately destroys him.continued on page 10

6

Bleek Gilliam (Denzel Washington) is managed by his best friend, Giant (Spike Lee).

By Eugene Holley, Jr.Photos by David Lee-

7

III~

~I

Mo' Better Blues

knew it was pointless. Still, when

Bleek (Denzel Washington) showed up at Indigo's

Uoie Lee) I sat there hoping that another lllan

would lean over the banister. "Honey, who's at the

door?" he would say. But no, this is Spike's world,

where WOlllen (except for Nola), typically wait on

and for lllen. So, after an obligatory scolding-he

ignored her phone calls and the letters for over a

year:-Indigo allows herself to get carried away, legs

in the air, by her knight. So, despite the richly ro

lllanced celluloid, Mo Better Blues is a Spike Lee

joint after all.

And while it is refreshing to see "Black love" on

screen, Lee's depiction is insincere. The relation

ship between Indigo Uoie Lee) and Bleek (Denzel

Washington), in particular, lacks personality and ro

lllance. The only selllblance of chelllistry between

the p~ir appears late in a brief and lllisplaced scene

in which they discuss first loves. Clarke (Cynda

Willi~ms),Bleek's other love interest, is fairly con

vincing as a seductress though she does not even

feign affection for Bleek or his rival, Shadow

(Wesley Snipes). She lllerely "lllO' betters" one or

the other sufficiently to facilitate her career.

To be fair, the WOlllen in Mo Better, though still

peripheral characters, are lllore life-like than the

WOlllen in School Daze or Do The Right Thing. They

have jobs, hOllles and aspirations, not just nubile

continued on page 11

8

Photos by DavidLee

Sleek Gilliam (Denzel Washington) enjoys a passionate love affair with aspiring singer Clarke Betancourt (Cynda Williams).

THE MUSIC

Giancarlo Esposito stars aspianist Left Hand Lacey.

Eugene Holley, Jr. is the assistant director of the NationalJazzSeIViceOrganizationinWashington, DC. He is a contributortoJazzTimesandTower Record'sPulse magazine.

"proper attitude for the music."Wesley Snipes, who portrays Shadow Henderson,

Bleek's tenor saxophonist and rival, was gre\atlyinfluenced by Thelonius Monk. "The archetype forme is Monk. I can relate to Monk totally. As anactor, I was inspired by all of the tapes I saw of him,listening to his music, and by how he perceived artand music. I immediately had a connection to it. Ina roundabout way, I'm Monkesquewith my acting.

I'll do something out of theclear blue sky not knowingwhether it's going to work ornot. And that's the way Monkwas."

In addition to Washingtonand Snipes, Bill Nunn andGiancarlo Esposito play bassistBottom-Hammer and pianistLeft- Hand Lacey, respectively.The fictitious quintet alsofeatures jazz drummerJeffWatts (formerly with WyntonMarsalis and currently withbrother Branford) as "Rhythm"Jones in his first acting role.Originally scheduled as a consultant, Watts was given theacting assignment because ofthe difficulty of duplicating thecomplex rhythmic patternsnecessary for a believable performance.

In addition to commandingperformances and Ernest Dickerson's always brilliant cinematography, the movie features

exceptional music writterl and performed byBranford Marsalis and his Quartet featuring Terence Blanchard. Bassist Bill Lee wrote the originalscore. Also featured in Mo' Better is the music ofMiles Davis ("All Blues"), Wayne Shorter ("Footprints"), Cannonball Adderly ("Mercy, Mercy,Mercy"), andJohn Coltrane ("A Love Supreme").

Although this film will probably not do as well asDo The Right Thing at the box office, Mo' Better Bluesshould attract young Spike Lee fans who may havehad little or no exposure to jazz and inspire them

to check out Monk,Miles, Coltrane, andthe rest of the giants.If Mo' Better pulls thisoff, it will have donemore for jazz thanany movie before it.•

"More of aquiD than anarrative, Mo''ene,lUakes up lor its loosely constructed plot and

faulty dialogue with explosions of fertile color,

teare, and sound."

continued from page 6

A far cry from last year's Do the Right Thing, Leeuses music, camera angles, dialogue, lighting, andcolor in this film much in the same way that a jazzmusician spontaneously arranges harmony, rhythm,and melody to create the completed composition.More ofa quilt than a narrative, Mo' Better makes upfor its loosely constructed plot and faulty dialoguewith explosions of fertile color, texture and sound.

Lee says he decided to workon the film after he saw Bird,Clint Eastwood's 1988 filmabout legendary jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker. "It was such adark film, it was raining in everyscene, it really didn't speak of atrue Mrican-American existence. For me, it was just toobleak."

In his last performance, thelate Robin Harris, to whom thefilm is dedicated, provides Mo'Better's comic relief in the roleof Butterbean, the MC for thejazz club Beneath The Underdog (which, incidently, was thetitle ofjazz bassist CharlesMingus' autobiography).

The set's technical advisorsincluded bassist Michael Fleming, who played in Bill Lee'sNew York Bass Violin Choir,saxophonist Donald Harrisonand trumpeter Terence Blanchard. Blanchard, formerly ofthe Harrison-Blanchard quintet(with Donald Harrison) and Art Blakey'sJazz Messengers, worked as Washington's coach throughoutthe shooting of the movie. "I worked on him gettinghis embouchure (the correct placement of the lip andtongue to the mouthpiece) and gave him tapes ofthe actual music he was playing. I wanted get him toa level to where he could actually play the melodiesof the tunes in the movie," Blanchard said. "Denzelwent beyond my expectations and his own. Whenyou see the movie, you'll see Denzel playing thenotes."

In addition to teach-ing Washington thetechnical aspects oftrumpet playing, Blanchard also had himstudyJohn Coltrane,Miles Davis, OrnetteColeman, and Thelonius Monk throughtheir music and vide-otaped live perform-ances to develop the

10 '

THE MANcontinued from page 8

bodies. And at least, Lee resisted the temptationto turn the nightclub scene where the two womenappear in identical, Bleek-bought, red dresses intoa cat fight. Though such a turn of events wouldhave been consistent with the film's machismosubtext, we would have been deprived of Bleek'ssmooth-talking his way out of the dilemma sosuccessfully that we don't even know who endedup going home with him.

Mter Bleek's musical and, apparently, mentaldemise, both women do get what they wantClarke gets a steady gig, and Indigo gets the guybut both on someone else's terms. Clarke, thoughshe seems offended by Bleek's inference duringpillow talk that she wants him to launch her

singing career, doesn't find success as a songstressuntil after she beds the new bandleader. And,Indigo only merits Bleek's singular affe<;tion afterhe's flopped onstage.

Lee has said that Mo Better is a film about relationships, but the only relationship in this film that hasany depth is the one between Bleek and his ego. Although the conclusion of Mo Better implies that wifeand home are the ultimate panacea, we aren't convinced. The women that Bleek sleeps with, like theboys in his band, are merely the landscape for theglorification of Bleek' s "dick thing." Lee doescapture the myopia of the self-absorbed artist andhis inevitable alienation but fails to capture oursympathy.•Lett Proctor is a Washington, DC-based writer and editor.

Denzel Washington (Sleek Gilliam) and Joie Lee (Indigo Downes).

11

..by Kalamu ya Salaam

Wesley Snipes stars as ambitious saxophonistShadow Henderson

s~~. .

pike Lee says he really lovesand appreciates jazz music.If that's true then why didn't

he spend some time getting toknow jazz before he made Mo' Better

Blues? Lee's failure to deal with the details ofjazzin this film mirrors a problem that many of ushave: we think that because we are Black and loveour culture then ipso facto we know our culture,and, unfortunately,that's just not the case.

The key failure hereis that Mo' Better Bluesdoes not really dealwith jazz from either atechnical, artistic orbusiness standpoint.We never hear the catssay a word about theirmusic except forShadow (WesleySnipes), the tenorsaxophonist, saying thathe wants to make hismusic more accessibleto a broad audience,yet the imagery and theplaying in the filmmake it clear thatShadow is actually thestrongest voice on thebandstand.

It's Shadow who ishounded by Bleek(Denzel Washington)and Giant (Spike Lee)for taking long, longtenor solos (which ishardly what someonewho is trying to becomepopular with the masseswould be doing). It'sShadow who reachesback in the tradition to revive a W.C. Handy song.So, on the one hand, while the script says Shadowwants to sellout and go the pop route, the actionof the film shows it is Bleek, the oseriouso one,who writes and clowns his way through "Pop Top40." It's Shadow who upholds the integrity of themUSIC.

Even the soundtrack of Mo' Better Blues is gener-

12

ally lackluster until the conclusion of the moviebeginning with a Branford Marsalis treatment ofOrnette Coleman's "Lonely Woman" and endingwith extended selections ofJohn Coltrane'srecordings. Only two soundtrack numbers arestandouts. One is "Top Pop 40," a parody of popular music; the other is a brief burnout number,"Knocked Out the Box." "Top Pop 40," is excellently rendered, but it's not ajazz number. It's a

show tune completewith "mugging" fromthe band members.

The second excellentnumber is a trumpetsolo which aptly accentuates the off-stageaction of Giant, thetrumpeter's inept manager, getting his asswhipped in the backalley-except at thispoint Bleek doesn't.know that his boy isgetting beat up. Sowhy is this trumpeter,who up to this pointplays in a cool style,suddenly coming onwith a lusty, screamingsolo like he was auditioning for AlbertAyler (a tenor saxophonists who played"free" jazz in theextreme upper registerof his horn)?

Yes, the music worksas music. And, yes, it'stechnically on target asa counterpoint to the,alley action, but thescene defies logic.Spike Lee, here, as in

so many other places in this movie full of plotholes, does not even suggest what's going on.There are many other examples of the film'smusical shortcomings, but they all point back toeither an inability to figure out how to or a refusalto rely on the music in a film that is suppose to begeared toward uplifting jazz.

Furthermore,jazz as an art form is never dis-

Photos by DavidLee

Bill Nunn stars as bassist Bonom Hammer

cussed. The historyofjazz is never evenalluded to, and themajor musicians ofJazz are never somuch as mentionedas influential forcesand role models inthe lives of the "MoBetter" musicians.Neither the musicpresented in the filmnor any of the scenesdealing with the art or business of the music offerthe viewer any insight into jazz. In fact, peoplewho go to see Mo' Better Blues will not only leavethe movie unenlightened about jazz, they willactually have been subjected to some major misconceptions about it. In this regard, oMo' Betterois not even a noble failure.

Rather than show the musicians discussing theirviews on the major issues facing jazz musicianstoday, Lee resorts to presenting Bleek as thecliched, lonely, temperamental artist who will letnothing get in the way of his music or else Leewastes time focusing on contrived issues such asan in-band feud about the piano player bringinga woman into the dressing room.

Early in Mo' Better Blues, Bleek claims he wouldcurl up and die if he couldn't play music. At theend of the movie, he's alive and well and notplaying music. What was set up as the main conflict of the movie ends up being a non-questionas does every other conflict.

By the Hollywoodish ending of the this film-theex-trumpeter is now a family man (although weare never told or shown what kind of work hedoes), married to a school teacher (in an unbearably and unbelievably mainstream Americawedding), and raising a son who is suppose toremind us of the young Bleek Gilliam (through aconcluding scene which parallels the openingscene)-Spike Lee has totally undermined theintegrity ofjazz musicians. It's all a neat littlepackage of stylistic garbage.

The implication is that jazz musicians don't

raise families because their musicgets in the way. Theabsurdity of all ofthis is that most ofthe musicians whoactually play themusic heard in thefilm, TerenceBlanchard andBranford Marsalis,in particular, arefamily men. They

are the same age as those portrayed in the film,but rather than basing this movie on the real livesof real musicians Lee concocts images that are notconsistent with reality.

It's time for Spike Lee to expand h-is vision, andit's tim~ for him to employ talented Black writerswho ca~ produce scripts which reveal both thebeauty and the complexity of our lives and culturerather than scripts like this one that limp along_~n

fake hipness from cliche to cliche, generalizationto generalization.

The ultimate insult, however, is that the endingof Mo' Better Blues is dominated by the music ofJohn Coltrane. It's the ultimate insult becauseduring the period that Coltrane made his strongest music he also reared a family and had an amazingly beautiful relationship with a Black womanwho was both wife and musician.

During this portion of the movie, lovingly photographed scenes flow across the screen, offeringvisual accompaniment to some of Coltrane's moststirring playing. And what does Spike Lee do? Hetakes Coltrane's music and mates it with a storyline that completely contradicts the example thatColtrane offered.

Lee originally wanted to title this movie A LoveSupreme, the song for which Coltrane is best remembered, but Coltrane's widow, Alice Coltrane,would not allow it. Three cheers for Alice Coltranel' •

Kalamu ya Salaam is a New Orleans-based writer, music producer andarts administrator who has served as the executive director of the NewOrleans Jazz and Heritage Foundation.

13

How To Make Love to a NegroWithout Getting Tired is a comical and noncommittallitde film. Apart from its provocative and controversial tide, the film itselfrarely tantalizes, much less disturbs. In fact, ifit weren't for the tide, this film would havelong since been swallowed by the art housecircuit and forgotten, hailed by most whitecritics and dismissed by most Black ones.

A deliberately paced film, How to Make Lovefollows its protagonist "Man," a writer in exile,around in a-day-in-the-life fashion, usually forgetting to cue the audience to the fact thatthe film is about the genesis of a novel and itsultimate conclusion. The film also fails toconvince us that it is an exploration of theprocess of artistic creation, excluding us fromthe connections between the artist's experiences and his work and leading us insteadinto the tricky realm of casual interracial sex.

Haitian-born Dany Laferriere, the author ofthe book on which the film is based and coauthor (with Richard Sadler) of the screenplay, says it represents his answer to a question a white woman in Montreal once askedhim. The question: What do Black men talkabout when white "Tomen are not around?

Scenes from How To Make Love to a Negro Without GeUingTired from left to right: Man (Isaach De Banko/e) at histypewriter; Man andMilBicycleUe (Nathalie Talbot); Man andMil Literature (Roberta Bileau); Man and Bouba (Maka KoUo)in their Apartment.

I cannot disagree with hisassumption that the stink aboutthe film's tide smacks of an avoidance tactic. After all, who protestedThe Toy, the silly Richard Pryor ve...hicle, an equally offensive tide anda more offensive film?

'When I wrote this book andfilm I did not want to take anideology," he says. "I have putmyself in a position where anybodycan say this guy is a sexist or aracist. But I wanted people to behonest and discuss it. I did not findthat in America."

The truth is How To Make Love ismost problematic in the UnitedStates not because of its tide butbecause it deals with Black menhaving sex with white women, arelationship most AmericansBlack and white-are very uneasywith. Beyond the fact that mostoften when we've seen this particular relationship dramatized it hasbeen in the most demeaning andbase sort ofway, and beyond thepolitical issues of the cultivatedalienation of Black men and Blackwomen in the cinema, and evenbeyond the politics of beauty in theAfrican American community, thefact is that the pretense of thesanctity ofwhite womanhood, likeit or not, is as much a part ofAmerican culture as the animalization and mystification of the Blackman.

Unlike the relationship between

white men and Black women,which has been accepted as amatter of course in the brutaldynamics of slavery and colonialism and their residual systems ofinequities, white women and Blackmen have been categorically offlimits to one another, creating anaura of child-like curiosity, a fasci-

nation for the forbidden. Butrather than address this, mostcritics have howled about theoffensive tide rather than thetroubling and, to some, distastefulidea.

More disappointing, though, arethe missed opportunities of thefilm itself. Rather than explore thenature of Man's attraction to whitewomen, How to Make Lave simplypresents it as natural. The idea thatbeauty is personified in creamyflesh is never challenged. The relationship "between races, betweenwhite girls and Black boys," as Laferriere puts it, never questioned.

The nameless "Man," played bysculpted, god-like SenegaleseIsaach de Bankole, is a lighdy-elad(or unclad), carefree child throwninto a candy shop ofwhite women.Rarely, do we see the depth orinsight of Man, the artist, as anobserver or luminary. Instead, weare subject to his silence, his oglingofwhite women, and his occasional pouting. Any depth in Howto Make Laves characters comefrom Man's philosophizing Muslimsidekick, Bouba, the film's mostlikeable and well-roundedcharacter.

Still, Laferriere insists that thisfilm is revolutionary because two ofits three central characters areBlack intellectuals--one a writer,the other a philosopher-andbecause its drug dealers are white.But the film is anything but revolutionary in its continuation of thestereotypes its title seeks to ridicule. Much like Keenan WayansI'm Canna Git Yau Sucka, the filmoften comes dangerously close tostepping over the line betweensatire and reinforcement.

Although Laferriere says he'sgenerally pleased with the way hisnovel was translated to film."Maybe in the movie it was notclear eIlough, but in the book itwas very clear that only the readerwho's reading the book knows verywell that this is a writer," he admits.'The other characters in the novelthink that he's just a sex object."And, so do I.•

JacquieJones is editor ofBlack Film Review. ActorMadgi Barsoum assisted the author as translator.

Faculty Vacancy inVisual Media

One Year AppointmentSchool of Communication

Temporary one-year non-tenure track appointment available for The American University 1990-91 as Assistant Professor of Visual Media, in theSchool Communication.Responsiblities: Teaching undergraduate and graduate coursesin basic film/video production,basic photography, film/photohistory and media studies,script writing, and studiotelevision; student advising;assistance in facilities and equipment management;School and University service.

Qualifications: M.A.; professional backgrqund and experience in appropriate areas related to teaching interests andcapabilities; some technicalexpertise necessary; previousteaching experience preferred;evidence of production of publications interests and potentialdesirable.

Competitive salary dependingon qualifications and experience. Position subject to finalbudgetary approval. C#V, andthree letters of recommendationshould be sent to:Visual Media Search CommitteeSchool of CommunicationThe American University4400 Massachusetts Avenue,NW Washington, D.C. 200168017.The American University is an affirmativeaction/equal opportunity employer. Applications from women and minorities areparticularly invited.

15

by Francoise Pfaff

BFR: Tell us about your forthcoming film?Cheikh Ngaido Bah: My next film will be La vie

continued on page 19

Cheikh Ngaido Bah was born in Senegal in1949. In addition to his two feature-length filmsand three shorts, Bah has made his mark in thehistory of Mrican cinema as one of the foundingmembers of L'Oeil Vert (Green Eye), an organization of filmmakers and technicians whose aimis to work together to exchange or share thetechnical resources and means at their disposal.

This interview was conducted in Dakar, Senegal, for Black Film Review.

Born in 1946 in eastern Senegal, Moussa Bathily attended the University of Dakar where he earned aM.A. in history. He started his professional life as ateacher at the Alxloulaye Sadjii high school inRufisque. It was around this time, in the early '70s,

Moussa Bathily (right) talks to cameraman Bara Personnagesduring the shooting of Des Personnages.

that he became seriously involved in film criticism bywriting a regular film review column for 1£ Soleil, a Senegalese daily newspaper.

Later, after resigning from the school system, Bathilyreturned to Dakar, where he regularly attended filmscreenings at the Dakar Cine-elub. There he came intocontact with such Senegalese filmmakers as DjibrilDiop Mambety and MahamaJohnson Traore andstarted writing scripts. At that point Bathily became increasingly impassioned with cinema and subsequentlyworked as Ousmane Sembene's assistant during thefI1mingof Xaw (1974) and Ceddo (1976).

Mter such on-the-job training, Bathily started shoot- _ Ascene from Xew Xew, a film by Cheikh Ngaido Bahing his own fIlms. His best known works are Tiyabu Bira

---------------continued next page This interview was translated from the French by Francoise Pfaff,

author of The Cinema of Ousmane Sembene, A Pioneer ofAfrican Filmand Twenty-Five Black African Filmmakers and professor in the

Photo courtesy Moussa Bathily Department of Romance Languages at Howard University.

16

17

continued on page 18

also related to a number of problemswhich occurred during the shooting?Didn't you have very heavy rainswhich destroyed the clay villagewhich had been especially -built forthe film?

Bathily: I'll be brief on thisparticular point becausefilmmakers have a tendency tospeak at length about the problemsthey have experienced with MotherNature. I'lljust say that I haddecided to film at a given timebecause people told me that ithadn't rained during this seasonfor a hundred yearS' or more. I hadmy set built and shortly thereafter itrained cats and dogs for days.There is maybe some type ofconflict between God andfIlmmakers because the latter thinkthey are creators. So it seems thatGod forces filmmakers to be a bitmore modest....

BFR: Does the film focus on thevillage or the technical assistants?

Bathily: It focuses on both, andcontains amorous interrelationships.

manioc et a la sauce gombo, shot inWolof and in French, I try to be fairby refusing the type of Manichaeism currendy practiced inMrica, and according to which allwhite people are exploiters. Sincewe are in the post~olonialera, I feltit was both timely and appropriateto depict the relationship betweenMrican and Western countries witha certain amount of serenity. Myfilm describes the tribulations of agroup of French technical assistantswho live in a Sahelian village.

BFR: What was your film's budgetand how did you finance it?

Bathily: It ended up costingabout $1,350,000, which is animportant amount of money for a BFR: You worked as a journalist forfilm in Senegal. Petits blancs au awhile, and you have also written amanioc et a la sauce gombowas number of short stories. What dofinanced through my own savings these stories depict?and the profits from my previous Bathily: One of my short stories ismovies. It was also financed by the entided En circuitJenne ( Close Cir-SNPC (Societe Nouvelle de Promo- cuit). It's the story of heads of states

BFR: Does such a myth refer to the tion Cinematographique) of who gather to discuss the best waysmythical and stereotypical perception Senegal, the French Ministry of to avoid coup d'etats. While theyof Africa? Cooperation, the European are meeting, pyrotechnics are

Bathily: Yes, in a way, but the fIlm Economic Community, Channel 4 setting up fireworks. When the frre-also confronts Mricans, Europeans, (a British television station), as well crackers are heard, the heads ofand Mricanists-you know, these as other agencies and organiza- state believe a coup has fomentedpeople who have very fIXed ideas tions. against them.concerning the Mricans! Besides, I I would like to go further inam convinced that one should not BFR: Wasn't the cost of the film terms ofwriting. There is a greatremain in one's corner in this difference between being aspace age. We know as a fact that filmmaker and a writer. You needwe generally need Apastoralscene fromTiyabu Biru a film byMoussa Bathily collaborators toforeign money make a film,and technicians to whereas writingmake a film in equals solitude andMrica. Moreover, total freedom. Init also happens fact, I like thethat you get along challenge of awith people who blank sheet ofare not ne<;essarily paper. I've justBlack. By the same fmished a noveltoken, you may about a l~year-old

have a very poor boy whose motherrelationship with is a prostitute. Thepeople who are boy creates anBlack. artificial world

In Petits blancs au

Black Film Review: Bathily, what isthe theme of your latest film to date?Why did you call it Petits blancs aumanioc et a la sauce gombo?

Moussa Bathily: I wanted to illustrate the relationship betweenMrica and the West, but I wantedto do it in an ironic way. I did notwant to make a didactic film withgood people on the one hand andbad people on the other hand. Ithought that one could tackle thisfIlm in a humorous way. Thisexplains the film's tide, which is abit long, but which thumbs its noseat colonialism and at the myth ofthe cannibalistic savage.

(1978) and 1£ Certificat d'indigence(The Certificate ojIndigence, 1981).Tiyabu Bira is a feature film aboutpastoral life in Bathily,s nativevillage. 1£ Certificat do'indigence is ashort fiction film which denouncesthe inadequacies of Dakar's healthservices. His latest movie, PetitsbLancs au manioc et a La sauce gombo( lVhiteFolks &roed Manioc and OkraSauce), was featured at the 1989FESPACO (Panafrican Film Festivalin Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso) .

#tKJNtN 8atUrtcontinued from page 1 7made of dreams. He plays withwords which resound images andwith images which reverberatewords.

BFR: Does your writing influenceyour film language? Is there acorrelation between your two activities? Did you, like Ousmene Sembene, adapt some of your writtenworks to the screen?

Bafuily: I have done so only oncewith Des Personnages encombrants("Cumbersome People", 1976), inwhich literary characters kill theirauthor, whom they accuse ofhaving betrayed them. The shortstory and the film are both surrealistic. I like writing, but I have alwayswanted to make films. My familythought filmmaking was not aserious career so I studied historyand became a teacher whilethinking about cinema. I beganwriting while waiting to be able tomake films. Then, of course, whenI became a filmmaker I had muchless time to write.

BFR: Are you presently working ona film project?

Bathily: Yes, I am preparingl:4rcher Bassari ('The BassariBowman"). It is a feature film basedon the novel by Modibo SounkaloKeita. It tells the story of man whokills people, rich people. He doesso because they sold for theiradvantage the golden sword thatvillagers had asked them to sell toget money to fight drought. Thereare already some people who areinterested in this film: Channel 4 inEngland, WDR in West Germany,Canal Plus in France, as well asother television stations in Italy andelsewhere. Since my films havenever been commercially shown inMrica, I hope that l:4rcher Bassariwill be shown on the screens of mycountry.

The fUm will be shot in threelanguages to fit the story: Frenchwill be spoken by the bureaucrats,Wolofwill be used in urban homesettings, and ~assariwill be thelanguage used for scenes takingplace in the rural areas of easternSenegal. I am planning for a

18

budget of about $850,000 and theshooting of the film should takefrom eight to 10 weeks.

BFR: When we spoke earlier, youmentioned that you would like to go tothe United States. Why?

Bathily: I think that I havereached the limit ofwhat I canpresently express in Senegal. ThusI'd like to go elsewhere. Making afilm in another Mrican country,however, implies getting involvedin a co-production, which is notalways easy. So, I have anotherpossibility: to go to Europe or tothe United States. Depending onthe topic of my film I might be ableto fmd a producer and techniciansin Paris. Yet, to make a film inEurope would mean to illustrate astory with an Mrican content,which may be difficult for anMrican to do objectively. Theadvantage with working in theUnited States would be dealingwith a topic related to the Blackcommunity and questioning itspast.

BFR: And delineate its Africanity?Bathily: Right. I must tell you that

I have already been to New York,which is quite an exciting city. Iwould like to live in New York forsix months and explore it further.Moreover, I'd like very much toadapt one of Chester Himes' storiesto the screen. Ifsuch a dream wereto be fulfilled, I'd like to work withprofessional actors and shoot a truedetective story

BFR: In so doing you would increasingly lean toward -commercialcinema? Already Petits blancs aumanioc et a la sauce gombo seems tobe a step in that direction. All of thisseems far from the pastoral lyricismof Tiyabu Biro ...

Bathily: I think that I was verychaste when I made Tiyabu Biru.With time, one always prostitutesoneself to some extent in order toappeal to the public and be able tomake other films.

BFR: Could the future of Senegalese cinema be linked to a more

continued on page 28

Callfor

Entries

NationalEducational

Film &Video

Festival

21stANNUAL COMPETITION

Documentaries

Dramatic Features & Shorts

Animation II Classroom Programs

Medical/Health II Training/Instructional

Special Interest II Made-for-TV

PSA's II Film &Video Art

Student-made Docs &Narratives

Deadline: Dec. 1, 1990

Entry Forms:NEFVF

655 - 13th StreetOakland, CA 94612

415/465/6885

(}IJi~&tcontinued from page 16

en spirale ("Life in a Whirlwind")based on the novel by AbasseMbione. It narrates the life of ayoung man who lost his fatherat an early age. He was broughtup by his grandmother andwent to school until the age of15. Since he did not find adequate employment, he joinedthe army. Mter his discharge,his grandmother and his unclegather their meager funds andbuy him an old car so that hemay drive a clandestine taxi cab.By working at night, andthrough his passengers, theyoung protagonist soon getsintroduced to the drug underworld. As a result he [gets involved] with several situations,and [obtains] $830,000 after hisboss dies in a car accident. Thedrug lord is to be played byJean-Paul Belmondo. Isaac deBankole will play the main character. La vie en spirale will costapproximately $500,000.

BFR: These actors, who arewell-known in West Africa andFrance, should indeed facilitatethe commercial success of thefilm! But now let us speak a bitabout Senegalese cinema ingeneral. Senegal used to be at theforefront of African filmmaking.Today, although such films asCamp de Thiaroye ("ThiaroyeCamp") by Ousmane Sembeneand PE ("White Folks served withManioc and Okra Sauce") havejust been released, one has thefeeling that your country has lostpart of its importance in terms ofAfrican cinema. How would youexplain this fact?

Bah: Senegalese filmmakershave been responsible for thedecline of Senegalese cinema,particularly in the course of thepast five years. A system bywhich you could get subsidiesfrom the State has been in placefor more than 20 years, whichhas created some sort of welfarementality among filmmakers.This.system worked for a while,but I strongly believe thatSenegalese filmmakers should

mature and become more industrious because such subsidiesdo hot bring in profits. From1983' to 1988, the state gavemore than $3 million to Senegalese filmmakers and very fewfilms have been produced.

Modern filmmaking implies awide distribution network.Once, I had to confront[Ousmane] Sembene after hesaid in a 1986 press interviewthat his forthcoming epic,Samori, was going to cost $10million. He added that in theUnited States this type of filmwould cost twice as much. Whatwe were not told then [was] thatwhen Francis Coppola, for instance, prepares such a film heis not going to see the head ofstate to seek financial support.Coppola goes to see the distributor and he may tell him, "Ihave a film with MarlonBrando." The distributor' knowsthat this name will bring inmoney and he is interested inthe film project. This is a metaphor to tell you that Senegalesefilmmakers should think interms of business, especiallywhen a film costs millions ofdollars.

BFR: How could Senegalesecinema be revitalized?

Bah: You have to start fromscratch and adapt to the needsof the times. I maintain that onemust strengthen and link fiveareas: promotion, production,distribution, exhibition as wellas the technical infrastructures.Filmmakers should not solelydepend on the State; theyshould obtain bank loans andbecome accountable, even atthe risk of becoming businessmen. Whether one wants it ornot, cinema is a cultural industry.

BFR: We are thus, according toyou, reaching another stage in thehistory of African cinema; in particular, if one refers to the 1982Niamey Manifesto (Manifesto deNiamey). At that time, African

filmmakers wanted to developsociety through cinema andincrease the sociopolitical CGnsciousness of the masses. Are weleaning more and more towards acommercial type of African cinema?

Bah: I was at the Niamey meeting and a few of the things t~at

were said put me to sleep whIleothers made me smile. Why?Because Mrican filmmakers arebehind the times in comparisonwith Mrican ~lmgoers.ThefirstEuropean film was shown hereat the turn of the century, ~ndsince that time we have beenshown award-winning films andforeign commercial motionpictures.

One cannot talk about raisingpeople's consciousness whilemost of the Mrican viewers wantto see commercial films. To alarge extent, commercial filmsare the only ones able to attractwide audiences, especially nowwhen one can see good videofilms at home. Nowadays Mrican filmmakers have also tothink in terms of popularcinema.

What Mrican filmmakers donor talk about is the fact thatthey used to make films for Europe. Europe dictated whatMrican cinema should be, andEurope gave them a certainamount of money to financesome of their film projectsbased on scripts correspondingto European views of Mrica. Alot of scripts were written, or atleast edited, at the FrenchMinistry of Cooperation. In theold days such motion picturesreflected village life, classconflicts, or the clash betweentraditional mores and modernways in Mrica; now these filmsdeal with Mrjcan mysticalbeliefs as in Eby SouleymaneCisse. Mrican masses do notreally feel concerned with suchmotion pictures.

BFR: Some of Cisse's films likeFinye ("The Wind") have nonethe-

continued on page 28

19

Fresh Telllptress in Well Worn 'Def'by Arthur Johnson

It is truly commendable that 24-year-old actorJames Bond III stars in, wrote, produced and directed this all-Black-cast horror film for his owncompany, Bonded Filmworks. But his film, Def l7yTemptation, has a well-worn horror film plot: a demonic killer who lusts for human blood. The onlytwist on this old theme is that the demon is awoman in a tight dress (Cynthia Bond) and all hervictims are the men she picks up at a bar, takes toher apartment for four-star sex, then kills in a

variety ofbloody andbloodcurdlingways. In fact,the most startling scene ofthe film involves thevillainess sodomizing one ofher conquests.

Dej resemblesthe many "Exorcist" clones ofthe mid 1970s,including allBlack-cast

horror favorites such as Abby and Blacula. The onlything that saves Dejfrom complete horror filmcliche is its talented cast. Kadeem Hardison, fromTV's "A Different World," gets to show a sensitiveside and a great deal of big screen charisma. Freedfrom the broad comedy acting style required bysitcom TV, Hardison manages to flesh out hishomeboy' character as Bond's best friend, an exseminarian turned action film star. He's bothfunny and touching, indicating he may have anacting future beyond the Cosby dynasty.

Bill Nunn, Radio Raheem of Do the Right Thin~,provides a good deal of comic relief as a bar denizen who unsuccessfully hits on the ladies at the barwitl'} a never ending stream of outrageous pick-uplines and lies. And John Canada Terrell, the narcissistic muscleman of She's Gotta Have It, appearsbriefly as a bartender and victim. He appears--once again-in the nude.

Bond, however, as the film's main character,lacks the star quality and charisma to carry the filmand perhaps should have cast Nunn, Hardison orTerrell as the lead. Brief appearances by Freddy

Left: Kadeem Hardison in Def by Temptation. Below: TheTemptress (Cynthia Bond) seduces one of her victims (JohnCanada Terrell). .

Jackson and Melba Moore addlittle to the film. Cinematographer Ernest Dickerson, bestknown for his collaborationswith Spike Lee, is responsible forthe film noire look of De!

Still, the film's most laudablefeature is the fact that it represents the tenacity of today'sBlack filmmakers who canaccomplish the herculean task ofgetting a Black film into yourlocal movie theater.

The Other Sideby Pat Aufderheide

Mrican cinema has a soberand socially-conscious international image, and indeed its vitality has typically been linked to itssocial relevance. But there'sanother side to Mrican cinemaas well, that of lighthearted,often bawdy comedy. Bal Poussiere, written, prodlIced anddirected by Henri Duparc fromthe Ivory Coast, showcases thisstyle. Like the Zairian-comedy LaVie Est Belle, by Ngangura Mweze,it has roots in French farce aswell as showcasing folk humorand topical jokes. And like thatfilm, Bal Poussiere raises questionsabout the line between fullbodied humor and offensive reinforcement of stereotypes.

Bal Poussiere features the clashbetween city and country, andbetween men and women. Theheroine, Binta, is a young rebelwho balks at her city relatives'desire to make her into a maidand keep tabs on h,er; she wantsto go to school by day and partyat night. She's sent back home,where a lascivious polygamistknown locally by his nickname ofDemi-Dieu (half god)-wants toadd her to his five-wife collection. (The wives all disapprove.)Binta's father approves themarriage, and the flamboyantwedding shows off the husband'swealth, even though Binta haswarned her husband, "I'm not avirgin." The wedding night is acomedy of one-upmanship.

continued on page 22

ADifferent World lor Kadeem Hardisonby Lett Proctor

t's a long way from Brooklyn to Burbank, but for Kadeem Hardison, thebeguiling Dwayne Wayne of NBC's "A Different World," it's been apleasure trip.

He began training as an actor at the age of 7 with Earle Hyman (GrandpaHuxtable) and then later at Weissbanen, where students' performanceswere videotaped and then critiqued by talent scouts. His first paying job, atthe age of 14, was an ABC Afterschool Special, "The Color of Friendship", aportrait of race relations in public schools. The lead role in "The Color ofFriendship" was played by James Bond, III, director this year's Del by

Temptation, in which Hardison stars.Typically, work for the aspiring actor was sporadic. Hardison worked as a bike

messenger in New York between auditions. His big break came three years agoin the form of Dwayne Wayne. Darrell Bell, who plays his sidekick, was up forthe same part.

"I was in New York, and he was in L.A. auditioning for the same part. I'd callhim up and say, 'Yo, man, I got a callback on that Different World gig,' and he'dsay, 'Me, too,' and this went on until I was getting ready to go to L.A. to auditionfor it. And I called him up and told him, and he said, 'I'll see you there.' And I'mlike, hey, hold up now, he was a business major who dropped out of college todo Spike Lee's movie (School Daze) and now he's up for my part?! He .ain't paidno dues. I've been busting my chops for 11 years."

When it came down to auditioning for the network, though, the competitionhad been eliminated. Hardison had the floor. "I went in, gave them all somedap, told a few jokes, loosened everybody up a little bit and they asked me whatI'd do with the money if I got the part, and I told them I would buy a BMW-Iwas talking about a bike, but of course they thought, 'Little negro, soon as hestarts making some money the first thing he wants to get is a fancy car.'"

After two successful seasons on "A Different World," the network execsbought Hardison a BMW-a model car. By that time, though, he had alreadybought one motorcycle and traded it in on a second one, which he rode to LAfrom Las Vegas in the rain. Now, he's hoping to cut a deal with Honda to be aspokesperson. "I told tell them they could keep the money, just give me a bike!"He's planning a motorcycle trip from L.A. up the coast to· Vancouver, B.C. duringthe show's hiatus.

When he's not biking, Hardison still remains far from the world of Hollywood's glitterati. "It's always a "Who's Who" thing when .you go out, whereveryou go. I did all my partying at 18,19, 20 in New York. Now I've got everything Ineed at my house-a computer, Nintendo, a VCR, my comic books, my pit bull.The most I do is go to the movies on Thursday nights."

As for his future in acting, Hardison remains hopeful. "I'm very satisfied withDwayne Wayne, the way he's matured over the years, and since Debbie (Allen)took over, we have a lot more input over what the characters say and do." Heenjoyed working with Keenan Ivory Wayans on I'm Gonna Git You Sucka, SpikeLee on School Daze as well as James Bond, ilion Del. But, he explains, "Thatwasn't like work; it was like play because these dudes let you improvise. If itworks, they keep it, and if not, they don't.

He hopes to work on more small budget projects in the future and has nodesire to direct. In the meantime, Hardison will continue enjoying the fruits ofhis labor (he plans to buy a bigger bike, a "crUiser") and hopefully a long careerwith many credits. "When I auditioned for Performing Arts (high school) in NewYork, I didn't get in. Look at me now!" _

Lett Proctor is a Washington, DC-based writer and editor.

21

REVIEWS

continued from page 21

This is only the first of Binta'soutrages against her new husband's control, and the first ofhis problems in juggling hismarital responsibilities to hismany wives. The local great manis reduced to a figure of buffoonery by the savvy girl whowon't be tamed, although alongthe way the other wives begin torevolt.

III the process, the film makermakes the most of his leadactress' stunning physical attributes, providing close-ups ofjiggling breasts and a full-screenclose-up of buttocks. So eventhough the joke's supposedly onthe powerful polygamist, BalPoussiere also shamelessly exploits the prancing figure of thecitified girl. The movie also tries

hard to be a crowd-pleaser byoffering raucous scenes of cityentertainment, of lewd ruralbuffoonery and of the cultureclash between city and country.Perhaps the most self-consciouslyresponsible moment occurs inthe first few seconds of the film,when a prostitute attempts toengage a tavern patron, whoresponds, "And what aboutAIDS?" This question neverreappears.

Bal Poussiere was a smash hit atthe 1989 Ouagadougou biennialfestival of Mrican cinema, andwas also popular at the 1990Filmfest D.C. Its vigorous populism clearly has mass appeal, asdoes its lowest-common-denominator physical humor. But manyinternational audiences may findits exploitation of its central

character to step over the linefrom funny to crude. There arevery few Mrican womenfilmmakers, and so it may be abit of a wait to see what anMrican farce produced by awoman would look like. But itwould be very interesting to findout.

Without YouImagine a film with comedy

and music and lots of Black folkson camera at all times featuringsongs made famOllS by NinaSimone ("Four Women"), BillyPaul ("Me and Mrs. Jones") ,Sylvester ("Do You Wanna FunkWith Me" and "Mighty Real")and Prince ("Little Red Corvette"), plus rap music, a hot jazzcombo, and references to Diana

continued on page 31

TakeControl of Your Future at UDC

. 22

Stancey Stewart came to the University of the Districtof Columbia in 1981. His mind never showed up.

Stancey was playing hard in the street. .. having bigfun. His reward: Four "F's" and one "A". The playboystudent became a statistic...another dropout.

Doing back-breaking labor for small pay checks droveStancey back to the classroom in 1984. Stancey gotbusy. And he put his priorities in order.

He remembers: "At UDC, I learned how to learn! Ilearned how to apply myself to a task, how to improviseto achieve a specific goal, how not to rest on myachievements, and how to reach higher for the nextgoal."

He learned to be a winner, not a statistic!

The results: In May 1990, Senior Class PresidentStancey Stewart graduated, magna cum laude, with abachelor's degree in journalism, one of about 120undergraduate and graduate degree programsavailable at UDC. Pay raises and new job opportunitieswere offered by his employer. His self-esteem issoaring. The system is working for him now.

Stancey left behind almost 12,000 other smart peopleat UDC who are determined to take control of theirfuture, too.

Join them!

For additional informationCall UDC-2225, or write:

Office of Undergraduate Admissions, orOffice of Graduate Admissions

University of the District of Columbia4200 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20008-JJ1- .ac the smart choiceEEO-AA

OSCAR MICHEAUX KATHLEENCOLLINS SPIKE LEE EUZHANPALCY ST CLAIR BOURNE BILLGUNN MENELIKSHABAZZ ELLENSUMTER MICHELLE PARKERSONHENRY HAMPTON MED HONDOSOULEMAYNE CISSE YOUSSEFCHAHINE HAILE GERIMA SAUNDRA SHARP ROY CAMPANELLA,II REGINALD HUDLIN CHARLESBURNETT MEDHI CHAREF AVERYBROOKS AYOKA CHENZIRASTANLEY NELSON SIDNEY POITIER ISAAC JULIEN ROBERTHOOKS IDRISSA OUEDRAOGASARA MALDROR BILL DUKEJEAN-MARIE TENO ARTHUR ~SI

BITA KATHY SANDLER NEEMABARNETTE BILL FOSTER TOPPER CAREW ROBERTTOWNSENDMAUREEN BLACKWOOD JOHNAKOMFRAH MARTINA ATILLEROBERT GARDNER DEBRAROBINSON MURIEL JACKSONWOODY KING MELVIN VANPEEBLES DUANE JONES GASTON KABORE JULIE DASHBROCK PETERS DIDI PETERSYULE CAISE DONNA MUNGENRONALD WAYNE BOONE MARLON RIGGS BEN CALDWELLZEINABU IRENE DAVIS MICHELKHLEFI OUSMANE SEMBENEJAMES BOND III ELSIE HASS WILLIAM GREAVES • AND MORE

the vision.the voice.

From L.A. to London and Martinique to Mali.We bring you the world of Black film.

Black FIlm Review brings you news, reviewsand in-depth interviews from the most vibrantmovement in contemporary film. Published quarterly and recognized internationally, Black FilmReview is the foremost chronicle of the efforts offilmmakers throughout the Mrican diaspora. Andwith Hollywood commentary as well as features onother filmmakers working outside the mainstreamindustry, there is always something for everyone.

Subscribe today, or send $3 for a trial issue.You won't want to miss another one.

, , Black Film Review takes up where thelikes of Variety and Premiere leave offbecause itgives me in-depth articles andinterviews about film that's happening inthe other three quarters of the world-.the majority of the world. And as a newproducer, it's heartening to see acelebration offilm that reflects my effortsandmyperspectives. , ,

Gloria Naylor, Author and IndependentProducer of Mama Day.

~----------------I

DYES! Please start my subscriptionwith your next issue enclosed is $12.DYES! Please send me a trial copyenclosed is $3.

Name -----------

Address ----------

City --- State -- Zip ---,----

Clip and send this coupon with payment toBlack Film Review, PO Box 18665Washington, DC 20036L ~

23

t the American Film Market[AFM] , held in Beverly Hillsearlier this year, more than800 buyers from Asia, Eu

rope, the South Pacific, North,Central and South America metto purchase and sell the licensing, releasing, national andinternational distribution andexhibition of American film.Deals made at AFM, the largestcommercial audio-visual entertainment market in the UnitedStates, determine access tomoney and international markets as well as the prospects offinancial gains far down the linefor a large numbe'r of Americanfilms, some of which will neverbe seen in the US.

For the occasion, the roomsand suites of the Beverly HillsHilton were transformed intonegotiating salons, dressed 'palatially for those companiesthat could afford it and modestlyfor those that could not.

At AFM, deals are made atvarious stages of the productionprocess. Actress and filmmakerRae Dawn Chong, for example,was there searching for a distributor and post-production

funding to complete her filmcurrently in production in Canada while Wendell Harris,winner of the Grand Jury Prize atthe Sundance U.S. Film Festivalfor his first feature, ChameleonStreet, was there to market acompleted film.

Buyers from different nations,for example Embrafilmes, theBrazilian national film promotion organization, came to seewhat sellers offered for theatricalrelease, video sales and televisionbroadcast in their homelands.AFM newcomer JAMPRO, theJamaican Economic Develop-ment Agency, was on hand tosell Jamaica as a technicallysophisticated location site.

The Black films marketed atAFM varied greatly in subjectand production value as did thestructure of their sales pitches.Perfume, RolandJefferson's soonto be released feature, wasmarketed with a highlight onformer Love Boat star andfilmmaker Ted Lange. Lange isfeatured in Perfume, the story offour middle class Black women.Def by Temptation, on the oth'erhand, was over-promoted as afilm with an "all-Black cast."

AFM also featured A-ratedfilms such as Driving Miss Daisyand Milk and Honey, the story ofaJamaican who travels to Canada to find work. Although Milk'

and Honey, scripted byJamaicanplaywright Trevor Rhone, received critical acclaim in itslimited commercial release inthe US, it sold poorly at AFM,according to the sales rep.

Overall, the 1990 AFM essentially featured for 'sale B-rated,flashy action/adventure films.The majority of buyers, fromJapan and Europe, were lookingfor material to fill their rapidlydeveloping video and TV programming industries. However,the ending of the Cold War andthe uncertainty of the effecteconomic integration of Europein 1992 will have on the globalfilm industry slowed buying thisyear. In addition, many othercompanies are considering thefuture use of laser video, highdefinition television, live telesatellite links, and holographicimagery and were more cautiousin their buying.

Not surprisingly, there werenot many Mrican-American facesto be seen-besides the addedsecurity officers and custodialcrews. Eventually, though, a fewBlack sales representatives forthe releasing companies, lawyers,bankers, producers, and journalists made appearances. Still,Mrican-Americans are poorlyrepresented within this phase ofthe film ,industry.

To bolster and develop distribution of their films, Blackfilmmakers might focus more ontargeted market sales to foreignbuyers. "Rebound marketing'" tointended American audiencesmight be.a welcomed result.According to many sales reps atAFM, buyers want access to morevaried international, multicultural products, and less violent,more realistic, quality films areincreasingly sought. If AFM isany indication, the new andextended European markets,including former colonies, mayprovide new avenues for thedistribution of Black films.•

Black Film Review Associate Editor VictoriaMarshall is a LosAngeles-based freelance writer.She is also director of an international filmpromotion company, Reel World Imagery.

25

No Identity Crisis

No Identity Crisis co-author Melvin Van Peeble.

No Identity Crisisby Melvin and Mario Van PeeblesNew York: Fireside/Simon andSchuster Inc.260 pp., Illus., $9.95 (paperback).

by John Williams

In Melvin Van Peebles' secondmaking~f-the-filmbook, "NoIdentity Crisis", the 57-year~ld

maverick actor-producer-directorwho starred as "Sweetback" in thenow-legendary Sweet Sweetback sBaadasssss Song (1971) reemergesas "Block," the tough, no-nonsensefather of Mario Van Peebles'"Chip."

Sectioned into two parts, thebook chronicles the making of themovie Identity Crisis from its seemingly wacky genesis as a scriptcalled 'To Die For" all the way toits ultimate completion as a fatherson joint business venture.

Together, as partners in theindependent film productioncompany Block and Chip, Inc.,father and son confront do-or-dieobstacles in the gritty world ofguerilla filmmaking. Much likeSpike Lee's making~f-the-film