City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

-

Upload

city-limits-new-york -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

Transcript of City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

1/24

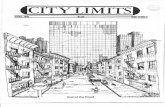

CITYLIMITSDECEMBER 1980 $1.50 VOL.S NO. 10

225 Parkside A venue, a recently completed Participation Loan building in north Flatbush, Brooklyn.

Participation Loans:The Two Sides of SuccessClinton Tenants PonderTheir Future, p. 9

A Look at CubanHousing Today, p. 12

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

2/24

Housing Under Reagan: Paradise Regained?Housing: Federal Policies and Programs, By John C.Weicher. Published by the American Enterprise Insti-tute, Washington, D.C., 1980.

by Marc JahrThe author of this book is a former Deputy AssistantSecretary of Economic Affairs at the U.S. Department

of Housing and Urban and Development. The publisher,the American Enterprise Institute, is a conservativethink tank frequently used by Republicans as the liberalBrookings Institute is similarly employed by Democrats.For that reason, this slim volume on federal housingprograms takes on special importance. From it, com-munity activists can gain a clearer sense of what to ex-pect in the coming four years.With Ronald Reagan's victory, and the Republicancapture of the U.S. Senate, attempts will inevitably bemade to embody the author's line of argument in Con-gressional housing legislation, and, unlike previoustries, may well be successful. The poor and workingclass residents of New York City's neighborhoods, par-ticularly its Third World communities, will suffer theconseq uences.Weicher's book begins with a brief review of the justi-fications advanced for government intervention in thehousing market. He then reviews selected research onhousing conditions in the United States, critiques pastand present housing subsidy programs, presents someCITY LIMITS/December 1980 2

possible alternatives, and concludes with a discussion oftrends in homeownership and programs designed to en-courage it.Throughout, he writes in a moderate, even scholarly,tone. But the tenor of the monograph is best reflected inone of his few moments of campaign rhetoric: "The vir-tual achievement of the original national housing goal isa major accomplishment of our society . . .The countryhas perhaps unconsciously sought new goals to replaceit, rather than celebrating the achievement. This attitudeis entirely responsible, although it tends to obscure stillfurther the extent of actual progress . . .. .The national goals alluded to by Weicher involve theelimination of units needing major repairs, lackingprivate inside baths and toilets, and suffering over-crowding. But it will be difficult for us to join him in thiscelebration. When we dance on the ruins of the SouthBronx, Brownsville and other devastated urban com-munities, the broken glass will cut our feet.In the course of criticizing this document it would bea mistake to be caught in the trap of defending the inde-fensible. The original liberal justifications for some ofthe federal housing programs were patronizing, and

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

3/24

their social goals inevitably went unmet. And many ofthe programs, most notably Section 235 and the FHAinsured home mortgages, have been characterized bymonumental corruption.Weicher's use of the failures, however, is entirely disingenuous. His contempt for the intended beneficiariesof these programs is evidenced in the comment that"Much of the earlier literature had ignored the possibility that the personal attributes of residents in poor housing, as well as or instead of housing conditions, mighthave a bearing on social problems." This is a somewhatmore sophisticated way of saying,'If it wasn't for welfare in this building, everything would be alright.'Weicher is a slumlord in academic robes.

The author also disputes the notion that federallysubsidized housing programs have any significant impact as economic countercyclical measures. His argument is basically that these programs are 'too little, toolate.' Even if one accepts this, and there is a complexargument involved here, Weicher neglects to allocateresponsibility for that "fact".

Sidestepping that political question serves the purposes of Weicher's argument. For, if the main rationales for government involvement in housing - improvedsocial conditions and as an economic stimulus - aredismissed, and one claims that the Housing Act of1949's basic goal - "a decent home and suitable livingenvironment" for every American family- has been met,then there remains little, if any, need for significantgovernment involvement in the housing market.At last, paradise lost can be regained. The "free"market can reign supreme. This is the ideological crossthat Reagan and Weicher will attempt to have us bear.In further dismissing public housing programs, heasserts, "There is evidence that subsidized housing production is in large part a substitute for unsubsidizedproduction that would have occurred in any case." And,"Private production has the greatest impact on substandard housing."To support this claim, Weicher invokes the "filteringprocess", a theory he admits is controversial. If the process actually exists, it simply amounts to the rich receiving the cream of the housing crop and the poor, thedregs. In New York City, blocks of abandoned buildingssilently mock his thesis. As does the incessant ringing ofthe city's Central Complaint number.Since HUD will not be closing its doors after the inauguration, and the constituencies committed to decenthousing will not roll over and play dead, what doesWeicher have in mind? While criticizing public housingand Section 8 subsidy construction programs as too expensive (and in the latter instance there is, for entirelydifferent reasons, su')stance to the argument), he speaksfavorably of the Section 8 existing housing program.In general, Weicher's solution is housing allowancesfor those who need them, such as Section 8 existing, onthe grounds that it would be less expensive, allow

3

greater freedom for the recipient, and serve more people. The effect this would have on an already tight housing market such as New York's, would be to drive rentsskyward (especially if accompanied by another Weicherproposal, the elimination of rent controls) and at thesame time further reduce the vacancy rate.Weicher also proposes housing block grants similar tothe Community Development Block Grant program. Heclaims these grants would give localities greater leewayin determining the form of housing assistance theychoose to offer residents. The abuses of the UrbanDevelopment Action Grants and the Community Development grants, even under current regulations, are wellknown. Laxer federal regulations will insure that increased amounts of funds will be diverted from low andmoderate income communities to more affluent areas.Similarly, the tendency to orient rehabilitation programs to the needs of banks and developers will be exacerbated.

In his conclusion, Weicher echoes his earlier theme ofself-congratulation: "But while the rhetoric is the same,the reality of housing has changed . . .The nation haslived for a long time with the sad rhetoric of big cityslums and tarpaper shacks, while in reality our housinghas steadily improved."Disneyland is coming to Washington. But the "rhet-oric" coming out of the allegedly chimerical "big cityslums" is bitter, not sad ..The challenge will be to translate that bitter anger into action that can defend and expand upon the housing gains won in the past. With advisors like Weicher, we expect nothing but griefemanating from the Reagan administration. 0Marc Jahr is a regular contributor oj photographs toCity Limits, and works as a housing organizer inBrooklyn._CITY LIMITS.

City Limits is published monthly except June!July and August/September by the Association of Neiahborhood Housing Developers,Pratt Institute Center for Community and Environmental Development and the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board. Other than edi-torials, articles in City Limits do not necessarily reflect the opinion ofthe sponsoring organizations. Subscription rates: 520 per year; 56 ayear for community-based organizations and individuals. Al l correspondence should be addressed to CITY LIMITS, 11' East 23rd St.,New York. N.Y. 10010. (212) 477-9074, , .Postmaster send change 0/ addresses to: 115 &st 2Jrd Street. NewYork. N. Y. 10010

Second-class postage paid New York. N.Y. 10001City Limits (lSSN O l 9 9 ~ 3 3 0 ) Editor. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. Tom RobbinsAssistant Editor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Susan BaldwinBusiness Manager . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Carolyn WellsDesign and Layout. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Louis FulgoniCopyright 1980. Al l rights reserved. No portion or portions 0/ thisjOU11Ul1 may be reprinted without the express written permission 0/ hepublishers. Cover pboto bJ Man: .....

CITY LIMITS/December 1980

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

4/24

Two Sides of Participation LoansNew York City is providing rehabilitation loans to apartment building owners at an un-precedented rate, and the program is having a strong impact on several neighborhoods. Justwho is benefitting from the loans, however, is a matter of debate.

~ ~ b y; s SAY!"GS WlK_r_l !Y-UIICOUI SAYINGS _ ..n(.IU'!;. .. ......... iw.......

PRIMARY-DAy-SEPT.-9":/980by Tom Robbins

After more than three years of stormy courtship, theCity of New York and the lending industry have joinedtogether in what appears to be a happy - if not moreperfect - union. The aim of this marriage is to providelow interest rehabilitation loans to multi-family buildings in "transitional" neighborhoods where mortgagesare difficult, and too expensive, to obtain. And whilethe partners are breeding merrily, a basic question remains: what sort of off-spring will this marriage spawn?Possibly no other city housing program is spendingmoney as fast, or having as great an impact, as the aptlydubbed Participation Loan Program. The City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, participant number one, using federal Community Development funds, provides roughly half the loan amount atone per cent interest. The second participant, a bank orconsortium of banks, antes up the other half at themarket interest rate. The combined effect is to cut theCITY LIMITS/December 1980 4

overall interest rate to the building's owner to wellbelow what the cost would be on the open market. Inaddition, the city provides mortgage insurance on theloan, tax abatements on the improvements, rent restructuring in all apartments, and, pledges of Section 8 rentsubsidies for tenants who qualify and cannot meet thepost-rehab rents.Recent talks with bankers, developers and city officials revealed sustained applause for the programwhich currently boasts 3,880 units either completed orunder construction, and another 5,600 units in the pipefine. Unlike other program pipelines, the valves are wideopen and the money is flowing freely. Flowing so well infact, that while the city has been whittling away manyprograms, and eliminating some, such as sweat equity,almost entirely, Participation Loans got a $5 milliondollar boost this year over its previous allocation. Of the$20 million given to the program this year, half of it is

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

5/24

already committed, and the other half identified withprojects already submitted. Participation Loan directorJim Peters doesn't expect to even look at a new application until next year."Two years ago it was a question of whether the program could work," said Peters. "But now, the volumehas built up and there is more demand than funds.We've been able to get the banks' full participation,

whereas before it was almost entirely our initiative."That initial nervousness was echoed by bankers whoare now highly supportive of the program. "Buildingowners and banks were extremely wary of getting involved with the city," recalled Joseph Bowen, AssistantVice President at the Citibank pilot project in Flatbush."But in 1979-80 things started to come together. Confidence in the program grew as standardization of theloans occurred." Citibank in Flatbush is now a lender in14 projects under construction, and has another 35 inthe pipeline."It's a highly effective program that has really gottenthings accomplished," added Roger Williams,who heads

the Community Affairs office of the Dime SavingsBank,which is involved in Participation Loans in Brooklyn and Staten Island.From 1976 to 1979, at a time when interest rates werewell below their present levels, the program was able toclose just twelve loans. Bankers and city officials describe this period as a start-up time, during which confidences had to be won and forms and criteria standardized. Once both these goals were accomplished, thework began in earnest.Some community groups have also joined in theapplause for the program. "It's been enormously successful," said Judy Flynn, director of the Flatbush Development Corporation. "In a fairly small area we'vemanaged to get 23 buildings in the program. We've followed right behind the work of our tenant organizing.In most cases we've worked with tenants in occupancy,and in others we've been able to checkerboard." Bychecker boarding, a developer moves a tenant into a v cant apartment until the rehab work is complete."Now that it's working, it's working quite well,"added Bob Blank, FDC's director of development. "It'sreally one program that can do rehab in a feasible way,without pushing rents through the roof."Participation Loans are having a clear and definite

impact on several neighborhoods where they have beentargeted. Washington Heights and Clinton in Manhattan, Crown Heights and North Flatbush in Brooklynhave thus far received the bulk of the loan dollars. Inthose areas, generally large, once stately, apartmentbuildings have been ushered into the loan program byowners, bankers or city officials. The rehabilitation hashad a spin-off effect as well: its activity has helped attract other, non-subsidized, development and rehabilitation.But, many critics of the Participation Loans fear the5

program's success may be largely one-sided. Ownersand developers receive loans otherwise unobtainable,tax abatements, rent increases and varying degrees ofprofit; banks make insured loans at greatly reduced riskto themselves, and, in the process, open up a neighborhood for further investment; city government makesgood on pledges to help revive deteriorating neighborhoods. But, at the same time, what happens to peoplewho cannot afford to live in the refurbished, andrefinanced, buildings?Low income housing is a scarce commodity and onceit 's gone, it's gone. It won't return to the hands of poorpeople unless the cycle of deterioration begins overagain, and then only in dilapidated, near uninhabitable,condition. The city's immediate response to the problem of postrehab rents, that, even though below market, may stillpresent either an extreme hardship, or be unaffordableto tenants is that ample Section 8 rent subsidy certificates are available. A number of catches exist,though. For one, certificates are only available to thosein tenancy at the time of the rehab - others must comeknocking at the door, certificate in hand. And for thoseLow income housing is a scarce commodity,and once it 's gone, it's gone. It won't return to .the hands oj poor people unless the cycle ojdeterioration begins again.

in place, the family size must match the bedroom countset by federal criteria - not exceed it or dip below. Cityofficials acknowledge this problem, but say it has beenlargely avoided by relocating mis-matched families.They do point to some, minimal, displacement as aresult of this.A family may also earn just above the Section 8 income limitations and therefore not qualify. One quarterof the certificate applications submitted by tenants inParticipation Loan biJildings have been rejected. Andthe sum total, as of November of this year, of certificates awarded to tenants in these buildings is 73. Although another 212 applications were in processing, andsome l,600 subsidies set aside for tenants, the differencebetween the promise and the delivery is a gap to the tuneof almost 1,'200 tenants presently paying the full postrehab rents.

HPD points to the city Housing Authority, whichprocesses the certificates and follows a complicated procedure as the reason behind the delays. Assistant Commissioner Jeff Heintz, who oversees the ParticipationLoan Program, believes there has been a good deal of"fallout" of tenants who apply for certificates but withdraw either because the wait is too long and paying thedifference between the actual rent and the subsidy is notthat great, or because "No one likes to have their in-

CITY LIMITS/December 1980

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

6/24

come audited."In one Clinton project which was completed in 1978,only one Section 8 certificate has been awarded to date.The landlord there says he has been carrying the othertenants at the 25 per cent of income they would be paying if the subsidies were in place. But it is not possible todetermine how many other owners have been as sympathetic.Even were the city able to immediately deliver on itspromise of rent subsidies, however, there remains therest of the building's units which are marketed at thelevel of cost determined by the refinancing and therehabilitation.With fluctuating interest rates - presently headedback up to the heights they reached last spring - theability to bring in projects at rents affordable to thepoor and working poor would appear to be nearly impossible, even with the best of intentions. A project onManhattan's Upper West Side presently anticipatesrents ranging from $285 for a studio to $595 for a threebedroom apartment - rents which are well below what

could be obtained on the open market in that boomingarea, but still beyond the reach of those for whom thefederal dollars were intended. Nor is that project suchan extreme example. In Crown Heights, rents in a building being rehabilitated under the program which has notenants in place are $90 per room. This is in an.area where blacks and Hispanics account for 85 per centof the population. In 1977 the median income for blackfamilies in New York City was $7,427, for Hispanics$5,848. Low and moderate income is a handy phrase forplanners, officials and even community advocates; butin New York City, it is basically shorthand forminorities.

"Most of our rents are clustered just below the ceilingof what is allowed under Section 8," said Peters."We're really talking about serving moderate incomepeople or middle income people." Heintz insists there isa benefit to those who are of low and moderate income,because "We are producing rents that are affordable."Overall, though, he sees it as "a neighborhood preservation program - it's a program that effectively intervenes in the cycle of deterioration. It's ant.i-abandonment and it helps shore up transitional neighborhoods."Lew Futterman, a Manhattan developer who has beeninvolved in Participation Loans for several years andhas complemented his more than 200 rehabilitated unitswith open market rentals and co-ops nearby the subsidized buildings, couches his support of the program insociological terms. "Historically, the upwardly mobilemembers of poor communities have tended to deserttheir neighborhoods, leaving a substantial gap to fill inthe role model needs of the younger generation. Thekids are left with no one to admire but the local drugpusher. This is a program to keep those who are tryingto help themselves in the community."CITY LIMITS/December 1980 6

The enabling legislation for Participation Loans, Article XV of the New York State Private Housing FinanceLaw, dtes the program as a remedy for a "seriously inadequate supply of safe and sanitary accomodations,particularly for those of low income." The law does notdefinelow income, but the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, which administers andmonitors the federal block grants out of which the loans

Overall [said Heintz] "it's anti-abandonmentand it helps shore up transitional neighborhoods."are made, does stipulate that low and moderate incomepersons be the beneficiaries of at least 75 per cent of thefunds. The question of whether the loans do providethat benefit was one of the major thrusts behind a complaint filed with HUD last summer by the New YorkCommunity Development Coalition.HUD's response was that as long as three quarters ofthe loans resulted in rents allowable under Section 8guidelines, they were an eligible use of federal dollars.The Coalition argued that even though most rents mayfall within that bracket, the city does no income screening or verification t o see who is actually moving into therenovated apartments."Beyond the regulations," lamented Brian Sullivan,ofthe Pratt Center who helped compile the complaint,

"the real question is whether people are already payingmore than they can afford. Because HPD doesn'tscreen, they have no way of knowing who is reallybenefitting." The Crown Heights section of Brooklyn is one neighborhood where Participation Loans have been heavilytargeted. There, 953 units are already completed orunder construction. Another 1,353 are in the pipeline.Among the most promising candidates for loans thereare the vast, 1920s-era, apartment buildings that linemuch of the area's major through fare , EasternParkway.Recently, the tenants in two of those buildings rejected their mutual landlord's proposal to do rehabsusing Participation Loans. Having seen rehabs carriedout in several other nearby buildings, including one at284 Eastern Parkway which had been emptied oftenants following a, suspicious fire and where rents arenow $90 per room, they eyed the developments in theirown buildings somewhat nervously."The trend here is definitely to displace," saidWilliam Grey, of 255 Eastern Parkway who presentlypays $375 per month for a 7 room apartment for his fivemember family. In October, when the Grey family wasrepeatedly the surprised host to visiting inspectors andengineers preparing a scope of work for the landlord's

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

7/24

proposed loan, their apartment boasted a collapsedbathroom ceiling and a cascading leak in the hall. Overone third of the tenants in the 89 unit building were onrent strike after having gone without hot water or elevator service for over a month. "This building is definitelynot a slum," noted Grey, "it does need work, but notthe amount they want to do. Besides, they haven't givenus good services since they took over the building. Whatreason is there to expect them to begin afte r they get theloan?"According to Jon Poole, loan officer for the Community Preservation Corporation, a consortium of 39banks that have combined to offer lower than marketloan rates and spread out the risk, a package was beingworked on for the building which would bring $15,000worth of repairs to each apartment. The opposition ofthe tenants to the rehab prompted the owner, WoodvilleRealty, to sell the building in early November. But ifthat was a disappointment to the owner, the decision oftenants at 61 Eastern Parkway to block a loan whichhad been in the works for over two years wasdevastating .. In the final stages of processing the loan, tenants inthat building decided they did not want to pay increasedrents for repairs they didn't believe they needed, or forservices they didn't expect to receive. Rents there wereslated to go to $78 per room. "W e looked at otherbuildings where rehabs were done," said resident EllaMurray, "and we decided we didn't want to go throughwhat those tenants had suffered." After 85 per cent ofthe tenants signed a petition rejecting the loan, both cityand landlord were forced to drop the project.The deal the tenants refused, according to HPD'sPeters, was "irreplaceable." With a private bank mortgage at ten per cent over thirty years, and the city providing $460,000 of the $752,000 loan, the effective rate,said Peters, "came to around five to five and a half percent combined. With normal increases under rent guidelines they would be at the same level in two years,without the rehab," he insisted. "It's nice to say in theabstract that people have a right to standard, affordablehousing, but we have to look at the programs that exist.The tenants are living somewhat in a fantasyland."

At what point can tenants step in and decide theydon't want to have their building go through an expensive rehab? In the case of 255 and 61 Eastern Parkway,the overwhelming number of tenants opposed decidedthe matter rather emphatically. But in other cases,where tenants are of different minds, the question ishazy. The city has told HUD it must have 70 per cent ofthe tenants in favor of a loan before they will okay it,but, according to Peters; that figure is "not yet operational." In buildings where there is a division with noone side having a clear majority, the city will do what itthinks best,said Peters .A recurring refrain from those involved in Participation Loans is that tenants must be willing to "pay a little

7

"It's nice to say in the abstract that people havea right to standard, affordable housing, but wehave to lookat the programs that exist. Thetenants are living somewhat in a fantasyland."more." Further down Eastern Parkway, at 446 KingstonAvenue, tenants are paying a little bit more for a loanmade to their landlord, David Salomon. For almost twoyears they have watched him carry out what they describe as a "shoddy, piecemeal" rehab. According toCurtis Trueheart, an organizer for the MetropolitanCouncil on Housing which has earned the enmity of nota few landlords looking for loans, "the cheapest possible stoveS, refrigerators, tiles, you name it," he said,"are being used in the- building." Tenants charge thelandlord has used inexperienced, untrained workers forbasic systems work such as plumbing and electric. Attempts to get HP D and the Community PreservationCorp. to intervene have been to no avail, said Trueheart.David Salomon is one landlord, though, said JimPeters, that HPD is presently not accepting applicationsfrom for more loans, based on what the department'sInspector General thought an insensitivity for havingpurchased a fire-ravaged building from indicted arsonist

CITY LlMITS/December 1980

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

8/24

Joe Bald. "We will take another look at Salomon in thenear future," said Peters, "to see if his management ofthe jobs has warrants bringing him back in."The issue of poor rehabilitation work - as well as thequestioning by tenants of the scope of work the landlordanticipates doing - comes up frequently. Tenants confronted with figures which can easily run into severalhundred thousand dollars for a large building balk atbelieving that much work is necessary.

Another building where tenants are suffering a severecase of "post-rehab blues" is 225 Parkside Avenue inFlatbush where David Salomon's uncle and former busi-ness partner, Abraham Salomon, is just completing a$2.2 million Participation Loan rehabilitation of 126apartments. Gwen Moody, director of the Prospect Lefferts Gardens Neighborhood Association, who has beenaiding tenants in the building, said there has been heatand hot water on one side of the building only, elevatorshave been repeatedly out of order, rents for the samesize apartments have been set at widely varying levels,and, causing not a little alarm to the tenants, ConEdison recently posted a notice that hallway lightswould soon be shut off unless the landlord paid his bill.

225 Parkside has a long history with North Flatbushtenant organizers. An almost vacant building in 1978, ithoused only a few rent controlled tenants. A series often suspicious fires had driven everyone else away. Instepped Abraham Salomon, whose first moves were tolock out the tenants who were still in place and beginangling for loan money for a complete rehabilitation.One bank he approached for financing turned himdown because, as a loan officer put it, "We couldn'tseem to find out enough about him." But funding wasavailable elsewhere, and with a city Participation Loan,Salomon was able to get his project off the ground.According to HPD and the banks that participate inthe loan program, each prospective owner is carefullychecked-out, from a management, as well as financial,perspective. In the case of Abraham Salomon, however,HPD saw no flags go up at the mention of his name,despite a long-standing reputation in Brooklyn andQueens as a poor landlord.Recently, while tenants at 225 Parkside were beginning to organize themselves, tenants of other Salomonowned buildings in Far Rockaway were meeting withcity officials to ask that careful scrutiny be given toSalomon's applications for more loans, particularlytheir own at 1012 Nameoke Street and 1011 NeilsonAvenue. Both those adjoining buildings have been submitted to the city as candidates for rehabilitation. Andtenants in both buildings say they have been repeatedlywithout heat, hot water and other essential services aswell as the subject of threats from the landlord that ifthey blocked his loan he would "freeze their asses offthis winter" and turn their buildings into a duplicate ofa nearby decaying multi- family dwelling.CITY LIMITS/December 1980 8

In addition to the Far Rockaway buildings, Brooklyntenant organizers provided documentary information tothe city on other neglected Salomon buildings. But despite the tenants' allegations, HPD, after holding up theclosing of a Salomon loan in Brighton for two weeks,decided Salomon was still someone they could workwith and trust to manage his buildings well."(Salomon) knows how to perform," said Peters,"He gets money into the project before the loan closingand has the confidence of the financial institutions.He's obviously a guy with substance and capacity." According to Heintz, "The community's concern doesn'tgo away. We'll run a check on him again the next timehe applies. But for the present we are not going to holdup his loans."

Back in 1971, the city brought the forerunner of Participation Loans, the ill-fated Municipal Loan Program,to a screeching halt. That operation left in its wake astring of indictments and $135 million worth of defaults.Among the problems were little, if any, screening oflandlords and loans which should never have beenmade. Since then a number of safeguards have beenestablished, and the new loan program is hardly aduplicate of its predecessor. While some projects havehad to have their mortgages re-opened and more moneypumped in, there have been no major flops so far.Several non-profit community groups are also experimenting with the program in attempts to produce lowincome rentals and cooperatives, using other funds tooffset the steep rent increases that would otherwiseresult. And even the most severe critics of the programbelieve it has an important role to play. Suggestionshave been made that perhaps there are alternative methods for financing the loans, without using scarce federalfunds which are badly needed in programs that directlyserve low income people.There's no doubt buildings and neighborhoods arebeing turned around. The question is, for whom? 0

Media Assistancefor Community GroupsFor community groups that would like to use films,slideshows and even videotapes to strengthen and support their organizing work, a new non-profit resourcegroupois now available to help. The Community MediaProject will help groups locate appropriate media, andthe needed equipment, as well as organize publicity forthe event. For more information call (212) 620-0877 orwrite Community Media Project, 208 West 13th Street,New York, N.Y. 10011. 0

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

9/24

The Cityand ClintonTenantsSparon LeasesA short stone's throw from where the NewYork Convention Center is beginning to rise,tenants in low income, city-owned buildings arefinding their situation precarious. And they arewondering whose side the city is on.

by Susan BaldwinThe young man paced the sidewalk between thebuilding he calls home and a scarred and nameless fueltruck disgorging its oil at the curb, and wondered aloud

to a visitor about his future in this city-owned midtownManhattan tenement that the Convention Center andWestway have made suddenly desirable to City Hall.Joe Restuccia lives at 457 West 35th Street andwonders how long he will be living there . Until a fewdays before this cold and wintry sidewalk interview,Restuccia was sure that a dead slumlord was going toreach from the grave to buy back his building under thecity's easy installment road to "redemption" by payingback taxes.The final day for the buildings' redemption - November 3rd-came and went without Henry Hof's agentspringing for the back taxes. But, the status of thebuildings is still uncertain, and the tenants' associationis worried abou t the future.The city has owned Restuccia's and two adjacentbuildings since May, 1978, because the former ownerHenry Hof, Jr. - refused to pay taxes and refused tomaintain his property.

9

Joe Restuccia

But, the city has had very little to do with running455, 457, and 459 West 35th Street - three self-sufficient buildings that tenants began to manage in January, 1977, when the landlord was still around. And,after two fires, a long rent strike, and city ownership,the tenants signed an interim lease agreement with thecity in October, 1978, with the hope of being able to buytheir apartments as low income cooperatives at $250 -the city's self-proclaimed price for such propertytransfers."When Hof was here, there never was any heat . . . Hewouldn't even buy a full tank of oil," said James Crinion, a 30-year resident of 457 West 35th Street. "He wasnever around, and never took care of anything exceptcollecting the rent. We were always freezing all winter. . .And then, there was always the question of arson.We know he paid for that second fire."According to Crinion and other long-time residents ofthe 24 units that make up the West 35th Street c

CITY LIMITS/December 1980

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

10/24

buildings, tenants used to wait out front in the dead ofwinter hoping that fuel would be delivered."Finally, people got tired of waiting out in the coldfor a few gallons of oil, and they refused to pay rent.This is when we got of f the ground here," Crinion explained. "That's when he understood because he didn'tget his money. But, he still didn't care because all heknew how to do was turn homes into shacks. This wassuch a lovely house before he took it over."From late summer until early November this year, theresidents of these three buildings were sure that bizarrebureaucratic bungling or outright chicanery would leadto Hof's estate reclaiming their homes by paying some$54,000 in back taxes to the city. It was August 26 whenRestuccia was told by the city's housing department thatthe Division of Real Properties (DRP) had processedredemption forms that, it claimed, had been lost formore than two years.

People Got Tired" I t sounded like a joke and then we realized that itwas being treated by DRP as real, and all we were beingtold was that these forms had been mislaid. They were

on a desk down there and had been mislaid, and it wasthe city's fault," said Restuccia." I f you believe that story, you have to be kiddingyourself," said Eben Bronfman, housing specialist forAssemblyman Richard Gottfried (D-Man.), whose district encompasses this area north of Chelsea and south

of Clinton. "I don't clean my desk very often, but tolose something for over a year-and-a-half and then findit, something's fishy."Under the city's current tax foreclosure policy, a property owner risks losing title to his property if he owesmore than a year in taxes. But, he is also permitted fourmonths beyond title-taking by the city - known as themandatory redemption period - to pay his back taxes.In the case of Hof's West 35th Street properties, theredemption forms reportedly surfaced not only twoyears after title had passed but also after the' redeemer"himself - landlord Hof - had died. According to stoicDRP officials, "We had to process this claim becausethat's the law."But laying Hof's ghost still leaves the 24 tenant families of West 35th Street as potential candidates for displacement from their homes and neighborhood. Mostare older people, and of these, most have lived in thearea all their lives. As they view their situation, theironly chance to remain in their homes and neighborhoodis to buy their building under the city's $250 per-unitlow and moderate income cooperative policy.

"I've lived in this apartment 50 years, and I love ithere," said Angelia Ventura, of 458 West 35th Street,who was born several doors down the block. "I couldhave gone to Jersey like some of the rest of my family,but I chose to stay here. This is home to me and there'sCITY LIMITS/December 1980 10

no reason why I should be moved out. I pay rent. I'vealways paid rent. But, my, how things have changed. Iused to pay $26 a month and this place was a palace.Everything was spotless, and then Hof got hold of it . . .That was the beginningof the end."The rent roll, which has been restructured by thetenants' association, runs from $85 to $225 a month andprovides just short of $2,500 a month to take care ofrepairs and fuel. The buildings are part of a fuelcooperative, and through this association, are able tosave money.SO Years

Community residents understand when tenants referto the Hof regime as the beginning of the end. "Theyalways had services there because there were twobeautiful sisters who were owners and cared abouttenants," said a passer-by, who is also a "Hof" tenantelsewhere in the neighborhood. " It was a horrible thingwhen he got hold of those buildings because they werenice. All he had in mind was to run them down and hedid just that."The buildings were owned for more than 40 years bythe two sisters, who lived in 455, the smallest of thethree buildings. Hof purchased the properties in 1972and from then until the tenants' rent strike in January,1977, the buildings and services went dramaticallydownhill. Also, during this period, the tenants droveHof's superintendent out of the buildings after theyfound out he was trafficking in drugs. In addition, theyundertook the repair of the roof and of major waterdamage at 457, where the boiler is housed, in the summer of 1977 after a suspicious fire.

Lack of Protection"We wouldn' t be here today if it had not been for thedetermination of the tenants ' association," said Restuccia, who lives in one of the top-floor apartments at 457

that suffered extensive damage during the second fire."This is what is so insane about this situation here. Thetenants are allowed to struggle hard to hold onto theirbuildings, and a dead slumlord is almost allowed tocome back and take them. And then, you have to askyourself, 'I s there no justice?' . . . When the city takesover buildings and encourages tenants to run them,there should be some built-in protections."According to James French, of 316 West 36th Street,head of The Coalition of Concerned Citizens of Clintonand one of the founders of the citywide Tenant InterimLease (TIL) Coalition, this problem of lack of protection in future ownership is the major dilemma faced bytenants who have been managing their buildings withthe hope of buying them as low income cooperatives."They tell us to get liability insurance, fire insurance,whatever, but we always have trouble pinning themdown about what they really mean about repairs, and

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

11/24

finally after we burn ourselves out taking care of ourbuildings and providing services for tenants, we find outwe can't own these buildings because they're too valuable - they're too close to the Convention Center,whatever that means," French asserted. French lives in abuilding on West 36th Street that the city also refuses tosell to the tenants because of its proximity to the Convention Center.The buildings on West 35th and 36th Streets, totalingsix, are old-law tenements. This means that the roomsare undersized; some have views of air shafts; and, inthe case of 455 West 35th Street, three apartments havebathtubs in the kitchen and water closets in the publichall area.

Gentrification"You would think that they would be happy to unload them on us - sort of a good riddance, but that

hasn't been the case," said Restuccia. "For somereason, we are being encouraged to believe that thesebuildings are very valuable.""Who knows what is going to happen with the Convention Center," Restuccia added. "We may be astone's throwaway, but we may really be talking aboutlight years." One of his and French's concerns is that thezoning for the area is ambiguous.The area is zoned M6-1 which means that any use, including light industrial, can be implemented, and, it isfor this reason, that Restuccia fears his buildings couldeasily become a parking lot or a site for a hotel to houseConvention Center visitors.According to one housing official who asked to remain unnamed, "The problem is 'gentrification,' andwe're being asked to go along with it . . .This is a hot

area, and I can understand that, but I do have problemsunderstanding it when people's lives and investmentsare at stake. It's wrong to allow people to spend moneyfixing up their buildings only to tell them later theyhave to get out to make way for progress."Angelina Ventura does not know what gentrificationis, but she does know about living in her apartmentunder a state of siege.

"That's a very fancy word, and we really don't knowwhat it means," she said, adding, "You can ask us aboutputting in a new boiler or laying some linoleum. Weknow about tha t."In the 'gentrified' area of Clinton, there are almosttwo dozen buildings in the interim lease program and,citywide, there are about 240 tenant families who partake in the program."W e always look to West 35th or 36th Streets just toknow what's happening," said Richard Maecker, a tenant leader at 408 West 48th Street."As you know, we tried to do everything right, and

we still don't own our building," Maecker said. " I t really was wrenched from us at the very last moment be-

cause of the city's unfair redemption policy." 408 West48th Street was redeemed in January, 1979, aftertenants had fought a long uphill battle to run the building and turn it into a tenant-run cooperative.Since then, the tenants have had to deal with aseriesof new owners who have offered few prospects to thebuilding. "We just hang on; that's about it," Maeckeradded.Maecker believes in his building, and, even as the tenant once again of a private landlord, has no problemsticking by it, but, he says, "I wouldn' t recommend thisplan for action for the old who live down here, andthere are many who fall into this category."

He also said that the city should take its programsmore seriously, noting that not only the tenants but alsothe city should be left with questions about why the programs don't work.An old man who could not remember how many yearshe had lived in the midtown Clinton area addressed theissue that troubles many observers."I am old and I am sure most people don't care about

that, but I am raising an even larger question - wheredo I go if I don't stay here?"Long, Uphill Battle

The old man's question seemed to have fallen on deafears in terms of the city's involvement. But AnthonyGliedman, commissioner of housing, had this responseto a City Limits inquiry on the West 35th Street situation. "I didn't know about their plight, but possibly weshould talk about a long-term lease."Tenants were not enthusiastic. "We don't want tohear about a long-term lease," said Ellen Paturzo, whohas lived at 459 West 35th Street for over 20 years.

"What does that mean? Just throwing us out after afew more years?" Paturzo added. "I came here after afire damaged my house at 34th Street and 10th Avenue.I have moved all over Clinton, but this is my home . . .And, I might add about this building, even though wehave had our problems and fires, this has not become aparking lot like my last home." 0COORDINATOR OF

COMMUNITY ORGANIZATIONMulti-ethnic program in northern Manhattan seeksexperienced person to supervise and conduct

diverse organizing projects. Fluent in Spanish.B.A. Required. M.S.W. PreferredSalary $16,000 plus benefits.

Send resume to:

11

Washington Heights-Inwood Coalition21 Bennett Avenue 13New York. N.Y. 10033

CITY LIMITS/December 1980

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

12/24

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

13/24

by Bruce Dale and Charles Laven

This past summer a group of 25 architects, urbanplanners and housing experts set out to Cuba to find an, answer to one basic question: Was it really possible for apoor, isolated island with limited resources to solve thehousing question, while a large rich industrial nationlike the United States could not? Our trip was structuredto learn about Cuba 's progress in the areas of urban development and housing policy. The group was composedof representatives from universities, city government,community- based organizations and technical assistancegroups. Most of us had not been to Cuba before. Wewere interested in seeing the effects of the revolution onthe country as a whole, as well as learning how housingproblems are handled in the context of a developingcountry with a socialist economy. Although the problems of building abandonment, city tax foreclosure,federal funding regulations and the like seem light yearsaway from a small island with an essentially agriculturaleconomy, we felt that a number of critical issues couldbe fruitfully examined. Questions about how scarce government resources are allocated, what systems of housing tenure, management, maintenance and developmentare used, how and with what focus urban developmentis controlled, are all capable of providing importantcomparative information.Our trip came at a time when U.S.-Cuban relationswere very much in the news and wererapidily changing.Over 120,000 people had just left Cuba to go to theUnited States. Although most news media here emphasized the political motives of the emigrants, in Cubamillions took to the streets to condemn what was interpreted as selfish economic motives for the flight. Thatmigration and its attendant publicity seemed tounderscore the more than 20 year hostility between theUnited States and Cuba. The most potent and damagingresult of this conflict was the institution of the blockadein 1961 ,which has affected all levels of life in Cuba. Amajor example of its impact on the housing field was theacute shortage of basic building materials such as cement, steel and wood, not to mention all the necessarymechanical systems like pumps, elevators, air conditioners and tools.Despite this background of hostility, we were warmlyreceived everywhere by both government officials andpeople on the street. We were free to go where wewanted and to do as we pleased. Some parts of our triphad been organized, including meetings with local andnational housing and planning officials, visits to schoolsof architecture and discussions with representatives oflocal government. We also visited a number of projectsin three cities and were able to meet people spontaneously in the streets and neighborhoods of the housingprojects we visited. In some cases we were invited intopeople's homes.

In a number of important areas the Cubans' progresdespite the blockade, is astounding. Shortly after threvolution the elimination of poverty through the deveopment of industry and agriculture was declared to be national priority. Although still largely dependent osugar as its main product, Cuba is now exporting number of goods and manufacturing others for locaconsumption. Simultaneously it has made progrestoward achieving national social goals in the areas ohealth care and education. Currently all Cubans receivgood free health care in a series of new hospitals anpolyclinics diffused throughout the island, especially ithe previously under served rural areas.

13

Free education, including the university, has allowCuba not only to eliminate illiteracy, but to also be abto export trained technicians to other third world coutries in need of assistance. A recent example of thisthe export of some two thousand doctors and engineeto Nicaragua.Though housing has not been a national priority Cuba, despite a lack of building materials anskilled labor, considerable progress has been madBefore the revolution, most rural housing was primiti- thatched huts called bohios with plain dirt floors anno sanitary facilities were home for most. Urban houing for the bulk of the population was little better. Nowhowever, it is difficult to find the urban shanty towns common in the rest of Latin America. And in rurareas the landscape is dotted with "hew towns and newconstructed housing, concentrating population anreplacing the bohios.A factory for the industrialized production of larwall panels for apartment buildings, donated by tSoviet Union in 1963 to replace thousands of homdestroyed by hurricane, reinforced the Cuban focus oprefabricated building systems. Cuban housing prodution has focused on industrialized building systemGiven the need for housing and the lack of skilled labothe prefabricated building blocks were welcome bCuba. Experimentation with different design elemenhas taken place and both low - rise and high - rise buildiare being produced.The traditional Cuban environment cannot, howevebe recreated in an apartment building of four or fivstories. At first, and perhaps even now, people apleased just to have a better house than the hovel which they lived before. We were told that in the begining everyone wanted the ground floor apartments, until they discovered that all the children in the buildinhung out in front of their bedroom windows, at whicpoint many began requesting the upper floors. Prolems of adjustment to the new housing as well as othsocial problems in the new projects were handled by thinnovative Committees of Neighbors, a form of tena

CITY LIMITS/December 198

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

14/24

association which were created in all the projects inorder to help new tenants get settled.During recent years Cuba has experimented with several systems of prefabrication. The currently popularsystems include one from Yugoslavia and one, theGiron system, developed directly by the Cubans themselves. This latter system is used extensively for two andthree story buildings such as schools, factories, polyclinics and some very comfortable motels.The predominant focus of industrialized new construction has raised the question of what to do with theolder stock. The Cubans strongly argued that much ofthe old housing, even in historic districts, was . originallybuilt for speculation, and , is too dense and of too Iowaquality to be worth saving. Although many recognizethe architectural value of some of the historic buildings,the general feeling is that better housing could be provided by the newer prefabricated buildings.The problems of the older houses have been intensified by the lack of supplies available for ongoing maintenance. National priorities have caused many necessaryrepairs to be deferred. In cases where there is danger tothe building or its tenants, maintenance crews will respond readily, but where there is no danger, it may notbe repaired at all. As a general rule tenants, whetherthey own their apartments or rent, are responsible forall repairs within the apartment. When the problem isbuilding-wide, like a waste line or roof repair, then thegovernment assumes responsibility.

Immediately after the revolution, Cuba passed a laweliminating eviction for any reason whatsoever. Afterguaranteeing everyone the right to live where they were,the new government cut rents in half and expropriatedprivate property (with compensation) from those peoplewho owned more than they could personally use. Theseapartments were either used for publi.c purposes or soldPhoto by Jill Hamberg

Renovated housing in Old Havana

CITY LlMITSlDecember 1980 14

to their tenants using rent as a form of payment. Largevillas were taken to be used as dormitories or for stateoffices. New housing constructed after the revolutionbelongs largely to the state and is often built by a factory or enterprise for its employees. The money necessary to finance such developments comes from the responsible ministry and is allocated nationally. Theresulting apartments are apparently first offered to employees of the enterprise on the basis of need and attitude. The building is considered the property of thestate and is maintained by the local government. Oftenthe local Committee for the Defense of the Revolutionsponsors beautification programs and maintains thegrounds.Unlike the United States, where a market of rentalsand sales determines the allocation of housing units,Cuba has no traditional market place for housing. Themain system for finding a new place to live in other thannew construction is through an exchange called the per-mula. People who wish to move ~ d v e r t i s e in a n e w s p a ~ per what type of housing they need or would like tofind, and what they have to offer in exchange. Complementary needs are identified and a trade takes place.Differences in apartment values such as more or largerrooms are balanced by adding to the exchange additional items such as refrigerators or stoves.

Discussions about housing in Cuba rarely bring mention of financing or financing mechanisms, nor,for thatmatter, the need for subsidies. Being a socialist nation,concern for profits or interest rates does not exist. TheCubans appear to accept the idea that when the government has the resources,housing will be built, and whenit does,not,everybody must make do with what there is.As a result of this system of publicly financed and supported housing, rent levels are set at a maximum of 10per cent of income for all tenants - a figure that is independent of the cost of developing or maintaining thehousing. One Cuban observer noted that the combination of low rent, free health care and free educationmeant that the average Cuban had a large percentage ofhis or her income available for consumer goods such astelevisions, washing machines and the like. He alsonoted that the shortage of these items was consideredone of the major causes of dissatisfaction.New developments in the housing field in Cuba andpossibly changes in the existing system may come aboutin the near future. I t is anticipated that the second congress of the Cuban Communist Party, due to meet thisyear, will raise housing to the level of a national priority. That decision would probably result in increasedpfoduction of new houses and an increase in the preservation activity in the remarkable historic districts ofcities like Havana and Santiago de Cuba.

The subject of renovation and preservation is a newand difficult issue in Cuba. Many planners and architects hold a fairly traditonal view of the merits of new

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

15/24

construction. We found this surprising and wonderedwhy the Cubans had not accepted what we consider tobe a progressive position in the United States. After all,we have" inally learned that the rehabilitation and repairof existing houses is a less expensive and less disruptiveway of upgrading neighborhoods. The Cuban positionwas particularly disturbing as the new construction theyfavored uses sophisticated technology resulting in highrise projects which are out of scale with the existinglocal environments. They argued that the taller buildings were essential as Cuba is a small island where landis scarce and the existing crowding in the old buildingsmake low - rise solutions inadequate. It seems likely thatthe emphasis on high rise industrialized housing willcontinue.Given the relative scarcities in the economy, it isremarkable how much has been achieved in housing. Including the use of volunteer construction labor much ofthat achievement may be credited to the wide-spreadparticipation that exists at all levels of Cuban society.Starting at the neighborhood level and through the election of representatives to the district, city, provincialand national assemblies, the popular institutions such asthe Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, theFederation of Cuban Women and Popular Power all

Planners' Network ForumsWestway - Bestway or Worstway? is the subject ofthe December 19 session of The City at Six, the 1980-81program of Network/Forum.Network/Forum is co-sponsored by the New YorkArea Planners' Network, the Forum on Architecture,Planning and Society; and the Center for Human Environments, City University Graduate School.Each program is held on Fridays at 6 p.m. at the CityUniversity Graduate School, 33 West 42nd Street (between Fifth and Sixth Avenues) in Manhattan.The calendar for the 1980-81 year is as follows:December 19, Transportation: Westway, an illustrateddebate - Elliott Sclar, Columbia University; CraigWhitaker, Westway planner; Marcy Benstock, Citizensfor Clean Air; January 23, Cuba Special, tour report;February 20, Urban Strategies: Politics and Policies,Ron Shiffman, Pratt Center; March 20, Urban Neighborhoods - Harriet Cohen, Adopt-a-Building; Fred

Ringler and Ron Webster, People's Firehouse; April 24,Urban Renewal: Displacement and Gentrification onthe Upper West Side - Bill Price, United TenantsAssociation; Councilwoman Ruth Messinger; May 15,Urban Decay: Quality of Life in the South Bronx -Jacqueline Leavitt, Columbia University; DanaDriskell, Bronx Community Board #3, CouncilmanGilberto Gerena-Valentin.This is the third year of the series. 0

encourage mass participation. When Cuba could not afford the allocation of skilled labor for the constructionof new housing, that slack was taken up by volunteerlabor. Unlike the housing market in the United Stateswhich first measures the potential dollar return of a project before committing resources, the Cubans firstmeasure human need.

It is this concern for the well- being of the populationthat led us to one important conclusion about Cuba.We have returned with the belief that the best way toassure Cuban independence is to allow Cuba to trade frely with the United States and its Latin Americanneighbors. The economic and political blockade whichtried to isolate and destroy Cuba has no t succeeded, andits continuation promises only to cause continued hardship to a people we now call friends and from whom wemay learn how to build a society responsive to humanneeds. 0Bruce Dale is the Director of the Management in Part-nership Program in the New York City Department ofHousing Preservation and Development. Charles Lavenis Executive Director of he Urban Homesteading Assis-tance Board.

Williamsburg Tenants HitPolitics in Takeover Try

Low income tenants in Brooklyn..'s Williamsburg sec-tion have been waging a long term battle with their land-lord and his brother, who was recently elected a civilcourt judge, in an effort to wrest their buildings fromthe family and start running them under the city's 7AAdministrator program.Philip Ritholtz is the owner of the buildings at 184,188 South Second Streets and 745 Driggs Avenue. Hisbrother, William Ritholtz, the newly elected civil courtjudge, recently divested himself of his interest in theproperty, but prior to this move, he served as the at-torney of record for these buildings which have been thescene ofsome 13 suspicious fires in the last three years.

15

The tenants went on rent strike over a year ago andhave been collecting rent to maintain the only occupiedbuilding -188 South Second Street.If they are successful in being appointed the 7A ad-ministrator, they are hopefUl that they will get betterservice from the city. At the present time, in addition toowing back taxes, Ritholtz has emergency repair liensagainst the buildings amounting to about $60,000.Bella Zuzel, an organizer with Los Sures, a Williams-burg housing group, who has been working with thetenants, believes the battle has been stymied in housingcourt for the past few months because Ritholtz did notwant bad publicity prior to election day, when he ran asthe Democratic Party choice.The case was scheduled to be heard late in November.CITY LlMITSlDecember 1980

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

16/24

Two Patrons of H - - - . esteading

Meyer Parodneck and Martin YoungMeyer Parodneck and Martin Young are no enigma tothe grassroots neighborhood housing movement. Theyhave been promoting urban homesteading for years,and if they were not around to make small loans to community residents trying to save their homes and neighborhood blocks, the housing movement in New YorkCity might well not exist as it does today."People should be more militant about their housing," Parodneck said during a recent interview. "We seegiving loans to people who want to work, who want toh.elp themselves, as good business, and our only fear isthat this movement will disappear . . . We are discouraged about its future."Through their foundation - the Consumer-Farmer- Parodneck and Young are able to lend seed money togroups involved in rehabilitation of their-homes throughsweat equity - a movement that involves neighborhoodpeople who would find it almost impossible to get creditfrom conventional lending sources."But, what we are finding is that tenants are their

own worst enemy," Parodneck explained. "Workingpeople who are skilled with their hands decide to fix upseveral buildings on a block, and the tragedy often isthat they are not able to own them after doing all thework. In short, what they do by all their good work isprice themselves out of their own neighborhood."Both men believe that tenants should become moremilitant about their right to housing, asserting that justas the right to a free education is guaranteed by thegovernment , so should this guarantee extend to the"right to shelter."CITY LIMITS/December 1980 16

But, in their estimation, what is wrong with the housing movement is that neighborhood people are not aggressive enough about securing this right to shelter."They are no longer lean and hungry enough," saidParodneck. "It's not the same as in the past when people had nothing but knew what they wanted. They aretoo polite. They should take their housing and not waitfor the government to hand it out because it won't."Although they view the city's tenant interim lease program (TIL) as its most successful alternative management program for residents in some 250 city-owned,tax-foreclosed buildings, Parodneck and Young arequick to criticize the scope of the program.The city, they argue, has the program but does notsign enough leases with the tenants. The city is not willing to make commitments to people about running andowning these properties that it cannot manage itself.Rather, they maintain, the city has a negative, not apositive attitude about the value of this land.Referring to the success of the urban homesteadingprogram in Baltimore, where the city is happy to givetenants homes for a dollar and make rehabilitationloans with the idea of getting properties back on thecity's tax roll, Parodneck said, "Our problem here inNew York City is that we are only committed to the realestate interests, the landlords. We don't even knowwhat commitment to people is."Alluding to the city's heavy subsidizing of ManhattanPlaza in midtown Manhattan as "obscene," Parodneck added, "D o you know what I could do withthat money? I could take that money and house thou-

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

17/24

sands in New York." According to his figures, eachhousing u"nit at Manhattan Plaza receives a subsidy ofabout $7,500 a year and will continue to receive this subsidy money for a total of 40 years.

Deploring the city's reluctance to encourage tenantmanagement and ownership under its stated sales policyof $250 a unit, Parodneck recently wrote in an articleentitled the Housing Dilemma in Consumer-farmer'soccasional newsletter: "More than two years have passedand to the best of our knowledge all we have to show forit is the sale of five multi-family buildings to tenantswho have occupied and managed them for years :"This woeful record was achieved in the face of analmost universal interest on the part of tenants' associations to proceed to achieve home ownership, when theprogram (interim lease) was announced.

"The unexplainable delay in implementing the programis frustrating to the tenants and devastating to thecredibility of the city, which seeks the support of thesesame tenants in effecting any turn around in the housingpicture.

"[The bureaucracy is] . . . so committed to the philosophy that shelter must be unavailable without paying atari ff to a landlord. These properties are worthless. It isthe occupants who give them value and there is noreason why they should not be the beneficiaries of thevalues they create."The Consumer-Fa:rmer Foundation has corne a longway since it sta:rted as a milk delivery "cooperative in

1937 and then decided to terminate this service andbecome involved in the neighborhood housing movement in 1970."But, have we even made a small dent in this move

ment?" Young asked. "The answer is simple - not atall . . . from the terrace of my apartment in the Bronx, Ican see more apartments destroyed by fires in a monththan Consumer-Farmer has helped rehabilitate in all tenyears of its activity. We may have helped rehabilitate1500 units since we started our work in this field. But,that's not even a drop in the bucket."Parodneck's and Young's modesty about their contributions to the neighborhood movement is belied byremarks from community groups who are constantlysending them letters thanking their foundation for itshelp.

I f it had not been for their revolving dumpster loanprogram, homesteading tenants on 985-7-9 and 993Amsterdam Avenue of Manhattan's Upper West Sidewould not be as far along in their rehabilitation project."We don't know what we would have done withouttheir support and patience while we dealt with the g9-vern mental bureaucratic red tape on our 927 ColumbusAvenue project," said Leah Schneider, planning director of the Manhattan Valley Development Corporat ion.

In a letter to the foundation, she added, "Not only didthe loan enable us to pay our workers who, because oftheir commitment, worked for weeks without pay. I tguaranteed the completion of the project and the availability of the so desperately needed housing." 0

It Works1TRY ADVERTISING INCITY LIMITSA marketing survey of 15 samplecommunity groups showed more than$14 million spent on rehab supplieslast year.For further information on displayand classified advertising rates call(212) 477-9074.

CITY LIMITS/December 1980

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

18/24

Displacement: A Park Slope Case In Pointby Michael Henry Powel l

November night is blowing down over BerkeleyPlace, bitter gusts of wind pushing their way intobrownstone stoops and stained glass windows. Walkingdown Berkeley Place towards Fif th Avenue, the southside of the street is a warm, soft row of renovatedbrownstones, with deep-brown oak doors, gas lightsand, inside the windows, cozy snarls of hanging plants.The north side of the block, however, does not evokesuch bucolic descriptions.There, a schoolyard and a row of ten, grey-brickwalk-ups line the street. Many of the windows arecovered w\th plastic insulators and broken, graffitiedfront doors bounce in the wind. At 15 Berkeley Place,Robert Shannon sits at the window, waiting for myarrival. "We don't have any bells, so I'l l just keep aneye out for you", he told me over the phone.Robert Shannon is a fifteen-year resident of the Slope."We moved here four years ago . . Even then this wasn'tthe greatest apartment around, but , at least we got thebasics and they tried to keep it up." Recently, however,Shannon and his wife were without heat or hot water forfive weeks before the city finally put an emergency shipment of oil into their furnace. Even now, wind draftsthrough the loosely-fitting windows and Mrs. Shannonsits on her hands, and later moves to the other side ofthe room.Mr. Shannon, at 6 feet 2 inches and about 220pounds, is a retired metal polisher. When he was working, he and his wife had enough money to get by andenjoy themselves. Now, however, they are on social security and his $200 dollar-a-month rent takes up almosthalf his income. Soon, this will not be nearly enough tocover the rent. His building is under new management,and, as Shannon points out, "They've been making itpretty clear that we aren't wanted here." The newowners, named Levy and Eisenberg, are lawyers with aninterest in Park Slope real estate.Five years ago, a mortgage to renovate a brownstonein the heart of Park Slope was hard to come by. Now, asmore and more middle income people converge on theSlope looking for housing with a close proximity toManhattan, renovation funds are not so hard to obtain.Old, serviceable brownstones are prime targets for gentrification, or, in more polite parlance, establishing afirm economic base for the community. As Mr. Washington, another resident of 15 Berkeley Place said,however, "We're part of the lower class, that's true, butdoes that mean we don't have any rights, or any place inthe community?"Washington stopped by Shannon's apartment on hisway out to the store. Like Shannon, he is retired with noCITY LIMITS/December 1980 18

place to move. "Let's face it, you can't find anythingfor a decent price anymore. The new landlords told meto get out, but , I just can't see it . . . Where are we goingto live that's safe?" The new owners have not acceptedrent from most of the tenants since August; all serviceshave been cut. Maintenance consists of whatever thetenants can manage. As Shannon put it, "I buy thingsto kill the rats and roaches, I pass out the mail. Basically,I'm the super . . . the landlord told us he won't do anything until he renovates."

The following day, I talked to Shirley Taliaferrow, aresident in 15A. A wiry, energetic woman withshouldedength corn-row locks, Shirley is angry anddetermined to stay in Park Slope. "These landlords,they come in and treat you like dirt just so they canrenovate the building and forget about you. When Iwithheld my money, Levy told me that if he gave mefour or five months he knew that my kind would spendthe money." Shirley did not spend the money and ahousing court judge ordered repairs. As she pointedout, though, "I had to give up my money first, so,ofcourse, there were no repairs."Taliaferrow has three children and has lived in theSlope for twenty years. She is getting by, barely, andcannot afford to leave. "Where can I go?" she asked."I've lived in the Slope all my life. They told me I couldlive in some project in East New York, but, I don't wantto live out there. I want a decent place to raise my family." As Shirley pointed out, "I haven't raised a familyjust to watch it disintegrate when we move."The tenants along the north side of Berkeley Placereluctantly agree, however, that their days are numbered. Taliaferrow sighed and rubbed her hands againsther shirt. "Oh, of course, everybody we know hasmoved. Into the projects, to Long Island, upstate,Staten Island . . . t' s tough to move out of someplaceyou've lived for twenty years." She looked aroundShannon's apartment, sizing up the cracked ceilings anddecaying door. "It wasn't this way when we came here,wasn't paradise, but. . . damn, it's cold! Nice as thisneighborhood is I can't raise a family inside here."Stepping out of the building, I saw a Hertz vanparked in front of 21 Berkeley Place, another Levy andEisenberg building. Ruth, a short, young, Puerto Ricanwoman, talked about her family's apartment as herfather and brothers loaded furniture into the van."We're moving. Heat? Oh yeah, can't you see how I' msweating?" Ruth 's family lived in 21 Berkeley Place foreight years, but now, she says, "There's only one familyleft, and, I think they're moving. Three nights ago, wehad a fire and tha t was the final straw. They've been try-

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

19/24

ing to get us to leave, and, well, that fire happened totake place right next door to us. Those kind of firesdon't hurt the building, know what I mean?" Ruth'sfather did not want to leave. "He's worked hard hiswhole life, but, he doesn't want us to burn to death . . .and, even if it was a junkie's fire, that doesn't make youfeel too good either."Further up the street, at 68 Berkeley Place, is anotherLevy and Eisenberg building. The last tenant left over

-Community Management SalesFive buildings in the city's seven-year-old Community Management program are scheduled to besold to two neighborhood non-profit organizations by early December.The purchasers of 47 units at $250 each of thislow income housing are West Harlem CommunityOrganization and the Manhattan Valley Develop

ment Corporation. These apartments willeventually become low income cooperatives andwill be sold to tenant-owners for $250 each.West Harlem will take over 220-222-224-226West 116th Street. Manhattan Valley, if all structural violations are removed and Section 8 requirements are met, will buy 951 Columbus Avenue.The planned sales of these Community Management buildings are the first in this program. In thecase of West Harlem, the monthly per-roomcharge will be $40, and in Manhattan Valley, $51.Manhattan Valley is still negotiating with thecity about bathroom conversions necessary toqualify its building for Section 8 certification. According to Jacob Ward, who represents bothgroups, the city has also agreed to underwrite asurvey by an independent engineer to be sure that951 Columbus is structurally sound. 0

Relocation Commissioner AppointedWilfredo Vargas has been appointed Assistant Commissioner for the Division of Relocation Operations forthe Department of Housing Preservation and Development. The Division is responsible for HPD's consolidation program which closes hazardous city-owned build

ings and relocates tenants to other apartments. The postalso carries responsibility for emergency housing programs, including the operation of two city shelters andthe supervision of hotels providing temporary housingto tenants forced to vacate their apartments because ofemergency conditions.Vargas, 34-years-old, served as administrator of theSouthside United Housing Development Fund Corporation, known as Los Sures, in the Williamsburg sectionof Brooklyn for almost four years. 0

19

four months ago, and a solid, freshly enameled door sitsfirmly in its frame. Inside, the walls are glistening whiteand thermostats are visible. An interior staircase leadsto the upper floor of what will be a four or five roomduplex. The front window is boarded over, but, a construction worker on the site, said, "I think they plan toput in some stained glass or a picture window. These aregoing to be real expensive apartments." 0Michael Henry Powell is a tenant organizer in Brooklyn.

Short Term NotesEnergy Crisis Heat Funds AvailableFor the second year, the Association of Neighborhood Housing Developers will administer an emergencyfuel loan program called the Energy Crisis Heat Fund.The Fund was set up in February, 1980 by a small group

of anonymous donors who loaned money to the Fundwith the stipulation that the amounts be repaid in full byAugust 31st of each 'heat' year.Under the plan, ANHD members and affiliates cancall the Association when an emergency 'no heat' crisisexists, either due to boiler breakdown or to lack ofmoney to pay for fuel.ANHD will either call an ANHD fuel supplier, or payfor delivery by the building's regular supplier.The amount available per loan is negotiable on abuilding-by-building basis. I f a delivery of one thousandgallons will supply heat until regular or emergencysources can take over, ANHD will provide the interim

gallons. I f larger amounts are necessary, the Fund willhelp as much as possible as long as the money lasts.ANHD works out a repayment schedule with each borrower, taking into c o n s i d e r a t i o ~ the building's ability torepay. All loans, however, must meet the August deadline. For more information,call Dick Hochwald at (212)477-9080.0

Free AccountingClasses for NonProfitsA series of 12 free classes in accounting and basic fiscal management are being offered for New York City

non-profit groups by Accountants for the Public Interest - N.Y., Inc. Eligible groups are those focusingdirectly on the provision of essential community needs- housing, energy, food, health and economic development.Classes will begin next February, but groups must apply by December 15. For further information, call orwrite Barbara Stab n at Accountants for the Public Interest - N.Y., Inc. 36 West 44th Street, Room 1201,New York City 10036. (212) 575-1828. 0CITY LIMITS/December 1980

-

8/3/2019 City Limits Magazine, December 1980 Issue

20/24

Alternative ManagementAfter Two Years:The When andHow ofBuilding SalesDebated

The alternative management programs for city-ownedbuildings, which have been the subject of discussions,dialogues, diatribes and a vast number of analyses,came in for their most exhaustive exploration thus far ata Manhattan conference in November.Convened as a jo int enterprise by community groupsand city housing officials, the conference broughttogether for the first time on a large scale, participants,planners and policy makers. Despite their brief history,the programs were described as being "at a crossroads"by both officials and community representatives whopressured for their creation. While the basic dilemma ofthe programs was posed as the how, when and whatform sales of the buildings to groups and tenants wouldtake, hanging over the 300 conference participants werethe results of the national elections and the prospect ofan unsympathetic administration at the helm, controlling the funds which now fuel the programs.Tenants, planners and government officials all offered varying approaches at the day-and-a-half confer-CITY LlMITSlDecember 1980 20