Chola: Sacred Bronzes of Southern India

-

Upload

vylet-eclair -

Category

Documents

-

view

480 -

download

25

description

Transcript of Chola: Sacred Bronzes of Southern India

CHOLASacred Bronzes of Southern India

This guide is given out free to teachers and studentswith an exhibition ticket and student or teacher IDat the Education Desk.

It is available to other visitors from the RA Shopat a cost of £3.95 (while stocks last).

1

FRONT COVER Detail of Cat. 13 Trident with Shivaas Vrishabhavana (Rider of the Bull)BACK COVER Cat. 14 Ganesha [reverse view ]

Designed by Isambard Thomas, LondonPrinted by Burlington

Sackler Galleries 11 November 2006 – 25 February 2007

AN INTRODUCTION TO THEEXHIBITION FOR TEACHERSAND STUDENTS

Written by Adrian K. LockeFor the Education Department© Royal Academy of Arts

IntroductionAn imperial dynasty that emerged in the ninth century, the Cholas went onto rule over much of southern India for the next four hundred years, duringwhich time they undertook an extensive programme of temple constructionthat transformed the landscape of the region. Rich endowments fundedthe ritual activities of these temples and bronze representations of Hindugods, especially those associated with Shiva and Vishnu, were speciallycommissioned from master craftsmen for ritual worship in the new temples.These figures, many of which are still the objects of devotion in templesa thousand years after their creation, constitute one of the greatest bodiesof cast-bronze sculpture in world art. It is these objects that are the focusof this exhibition.

HinduismHinduism, the religion of the Cholas, is a multifaceted religion that hascome to be specifically associated with India. Indeed the terms Hinduand India both have origins in the Persian word for the river Indus.Hindu literally means religion of the Indians.

India can be divided into four regions: the mountain chains of thenorth including the Himalayas; the great southward-flowing river valleyssuch as those formed by the sacred Indus and Ganges rivers; the highcentral plateau of the Deccan; and the coastal plains of the far south whichis where the Cholas rose to prominence. Marked by regional differences,there is a very strong emotional bond that ties Hinduism to the land of India.

Sanskrit, which became the lingua franca of Hinduism, is a language thatevolved through the presence of the Indo-Aryans who conquered northwestIndia in the second millennium BC and is the language of ancient scripts.This gives some idea of the complexity of Hindu, a religion which has evolvedfrom, and absorbed elements of, a wide range of influences over some fourmillennia. Sanskrit, an Indo-Aryan language, belongs to the Indo-Europeanfamily of languages that includes Persian, Greek, Latin and most Europeanlanguages. Sanskrit counts Gujarati, Hindi and Bengali as among its manylinguistic descendants.

The languages of the south of India, however, are not descended fromSanskrit but form part of the independent Dravidian language group, whichboasts some 73 different languages. One of the most widely spoken andpurest of the Dravidian languages is Tamil, hence Tamil Nadu, a living classicallanguage over 2,000 years old. Tamil was the language of the Cholas andwas, therefore, used to compose the poetry of the saints and the foundingtexts which can be found decorating temples. Dravidian can also be usedto refer to the region and people of South India.

Hindu belief is based on oral traditions from a wide range of influencesthat were passed down over generations, although some of these were alsorecorded in Sanskrit manuscripts. There is thought to be great continuityin Indian religion that originates in the period referred to as the Vedic,pre-Hindu India of the first and second millennia BC. The Vedas, whichmean knowledge, are texts that date from this period and collectively thisgroup of books is considered to be the foundation on which later Hinduactivity is based. There are four Vedas, namely Rig Veda, Sama Veda,Yayur Veda and Atharva Veda.

These are followed by two great Sanskrit epics of Hindu India calledthe smriti or remembered literature. The first of these is the Mahabharata,

CHOLASacred Bronzes of Southern India

which at more than 74,000 verses is one of the longest poems ever written.Perhaps the best known part of the Mahabharata is the Bhagavad Gitawhich describes the events preceding the battle between the Pandyas andthe Kauravas, when the Pandya leader Arjuna turns to Krishna for spiritualadvice. The second Sanskrit epic is the Ramayana which recounts the manyadventures of Rama, his wife Sita, his brother Lakshmana and the monkeygeneral Hanuman.

Hinduism is primarily a devotional religion which means that the presenceof a god or gods is acknowledged by the individual. These gods are usuallyworshipped in structures which can range from very simple man-madebuildings to very elaborate stone-built temples. Sculpture, painting andritual objects are used in the worship of these gods. Although the spacewhere the god is enshrined in a temple, referred to as the inner sanctum,is not normally very large, the temple complex can be extensive. Part of thereason for these large temple complexes is the need to provide space forprocessions, essential components of temple activity and Hindu worship.For the devotees, participating in processions and annual pilgrimages isa very important aspect of their devotion, as it allows the individual theopportunity to supplicate or offer thanks to the god or gods. The abilityto participate in these activities also allows the devotee to come into directcontact with the gods and allows the individual to make puja (offeringssuch as incense, fruit, milk and ghee-fuelled lamps) and, more significantly,darshan, in which the participant communicates with the deity throughdirect eye contact. Hindus also believe in the immortality of the soul andin reincarnation. Two central concepts of Hinduism are dharma, a complexterm meaning among many things duty, and karma, which determines thequality of present and future lives.

There are three main gods in Hinduism: Shiva, Vishnu and Devi reflectHinduism’s abilities for multiplicity, variety and unity. The majority of Hindusare either followers of Shiva or Vishnu. Temples, like the followers, devotedto either one of these two principal deities are referred to as Shaiviteor Vaishnavite.

A short history of the CholaBefore the middle of the ninth century the Cholas were one of a numberof powerful independent cultural groups jockeying for position in southernIndia, the region today known as the state of Tamil Nadu. Their rivals wereprincipally the Pallavas, the Pandyas, the Cheras and, further to the north,the Chalukyas. Together these groups vied with each other for controlover the rich fertile flood plains of southern India centred around thesacred river Kaveri. Little is known about the early Cholas until the riseof Vijayalaya (ruled ?848–871), whose exploits are known because theywere recorded in stone inscriptions and copper-plate foundation documents.

Taking advantage of a conflict between the Pallava and the Pandya,Vijayalaya captured the town of Tanjavur where he established a royal courtand founded the dynastic line of the Cholas. Tanjavur became the imperialChola capital which was later moved to Gangaikondacholapuram. Inaddition, Kanchipuram and Madurai both became established as importantregional centres. The Chola dynasty ruled for a further four hundred yearsduring which time they became extremely powerful politically, economicallyand, significantly, culturally. Although their fortunes fluctuated over thisperiod, at their height the Cholas ruled over much of southern India,

3

Cat. 1 [overleaf]Shiva as Nataraja (Lord of Dance) Eleventh centuryBronze111.5 × 101.65 cmThe Cleveland Museum of Art,Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund,1930.331Photo © The Cleveland Museumof Art, Purchase from the J.H. WadeFund 1930.331

The Chola territories insouthern India, c.850–1250Cartography by Isambard ThomasMap relief © 1995 Digital Wisdom Inc.

2

BAY OFBENGAL

INDIANOCEAN

CO

RO

MA

ND

EL C

OA

ST

Pennar River

Palar

River

Ponnai River

Kaveri River

Vettar River

0 100 200 miles

100 200 300 kilometres0

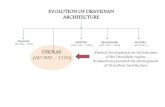

Cosmic Dance of Shiva as Lord of the Dance Nataraja (symbol of the eternal movement of the universe)

Drum damaru

A symbol of creation:the universe was set

in motion bythe regular rhythmof the dance. Also

combination ofmale and female

attributes

Abhaya position

blessing, protection,reassurance

Gesture of an Elephant

gesture of greatest strength

and power

Raised foot

gesture of liberation

Ring of Fire prabha

Representing the cyclical,cosmic concept oftime, an endless cycle ofcreation and destruction

Demon DwarfMushalagan

Representing ignorance

Fire agni

Representing destructionas well as energy in itspurest form but also creation

earlier iconography associated with the Pallavas, the image was adoptedand developed by the Chola monarchs, becoming established as a kindof royal emblem.

State patronage of the arts, including temple construction, decorationand substantial endowments of gold and jewellery, clearly reflects the wealthof Chola society, further demonstrating the status of their political andeconomic power. In order to get a sense of the magnitude of the Cholas’sdeliberate determination to demonstrate this authority, the Rajarajeshvaratemple at Tanjavur (fig. 1) which was completed in 1010 was, at 216 feet,the tallest building in India at the time. Its rich endowment includeda huge gift of 60 bronzes of which 22 were given by King Rajaraja I.

Hindu belief, like that of many religions, requires deities to fulfil publicfunctions and preside over specific festivities as well as those particular tothe temple in which they reside. To this end, small, portable images werecreated in bronze for use in processions. These were treated as physicalmanifestations of the gods themselves and were ritually bathed, dressed anddecorated with jewels and garlands of flowers inside the inner sanctum ofthe temple, a place of restricted access. When processed in elaborate templecarriages, these images became accessible to those individuals who were notallowed into these restricted areas of the temple (fig. 2). Great festivities and

celebrations accompaniedthese processions that serveboth a social and a religiousfunction which continue tothis day (fig. 3). It is worthremembering that it was onlyafter a campaign by MahatmaGandhi (1869–1948) that theinner sanctum of Hindutemples was made accessibleto Indians of all castes in 1936.

Chola BronzesThe bronzes are made usingthe lost wax process. Alreadyestablished at the time theCholas rose to power, thisancient process was takento new heights by artists and

bronze-smiths of the period. The process is an intricate one, imbued withreligious meaning. The various proscribed stages are laid down in anunwritten law.

Beeswax mixed with dammar (resin of the shal tree, otherwise known assallow-wood (Shorea robusta), the sacred tree under which Buddha lay downto die) is softened and used to create the desired image using a woodenchisel. Once complete, the wax model is hardened in cold water before beingencased in three layers of a finely ground clay. The mould is fired, melting thewax which drains out through specially positioned spouts. Molten bronze,an alloy of copper and tin, is then poured in and fills the now empty mould.Once the bronze has been allowed to cool down the mould is broken openand any finishing touches are made to the piece. Since the clay mould isdestroyed in order to remove the solid bronze sculpture each piece is unique.

7

The swollen, prominentmouth, with its wealthof sensual expressions.

The tenderness of themouth and of the eyesare in harmony.

Like a well of pleasurethe lips are surmountedby the wonderfully noblepalpitating nostrils.

The mouth, with itsdamp delights, undulatesas sinuously as a snake:the eyes are shut, rounded,closed by a seam ofeyelashes.AUGUSTE RODIN

‘I hold it a blasphemy tosay that the Creator residesin a temple from whicha particular class of Hisdevotees sharing thefaith in it are excluded.’ MAHATMA GANDHI

extending their control to include Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Indonesiaand north up the coast of the Bay of Bengal to the Godavari basin (in themodern state of Pradesh).

Two early rulers, Aditya I (ruled 871–907) and Parantaka (ruled 907–947),established the distinctive Chola architectural style in which elegant stone-built temples boasted well proportioned exteriors with a fine balancebetween carved detail and plain surfaces. Painted stone sculptures werethen added.

The most celebrated rulers during this Medieval period (848–1070) wereVijayayala, Rajaraja I (ruled 985–1014), who adopted an aggressive policy ofterritorial and maritime expansion, and his son Rajendra I (ruled 1012–1044),who consolidated Chola power throughout the region. The great agriculturalwealth of the region combined with control of the seaboard gave the Cholasaccess to the prosperous maritime trade routes which included those of theTang dynasty in China, Jewish traders in Aden (Yemen), the Srivijaya empirein the Malaysian archipelago and the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad.

Following the Medieval period the Cholas intermarried and formedpolitical alliances with the Chaluka dynasty to consolidate their regionalposition. The Chaluka-Chola period, lasted from 1070 to 1279, duringwhich time Kulottunga I (ruled 1070–1125), who oversaw an importantflourishing of the arts, is perhaps their most celebrated king. This periodalso witnessed the gradual decline of the Cholas, beginning with the lossof Sri Lanka and the increasing threat of a revitalised Pandyan empire tothe south and the Hoysalas to the north. Following the death of Rajendra III(ruled 1246–1279), the already shrinking Chola empire was absorbed bythe increasingly forceful Pandya monarchs.

Chola Patronage of the ArtsThroughout their rule the Cholas were great patrons of the arts andoversaw an extensive programme of temple construction. In some casesthis amounted to the reconstruction of earlier brick temples such as thoseundertaken by Queen Sembiyan Mahadevi, grandmother of Rajaraja I.Considered one of the greatest patrons of the arts, Queen Sembiyan’s firstknown temple donation is dated 941. She continued to patronise the artsuntil her death in 1006.

These stone-built temple complexes are externally richly decorated withdepictions of Hindu gods. Poems and music were composed to accompanyreligious processions and, like dance, consequently prospered during thisperiod. Each individual temple was endowed with great riches which tookthe form of gold, jewellery, textiles and bronze sculptures as well as meetingthe cost of providing food, sandal wood paste, incense and lamps. TheCholas also ruled that a proportion of income from communities shouldgo towards supporting temples which served to further underline theircommitment to, and the central importance of, religious worship.

There is no question that as part of their patronage of Hindu religionthe Cholas elevated the art of bronze sculpture to new heights. Althoughthe Pallavas worked with bronze, producing portable temple sculptures,the Cholas adapted and perfected the art, perhaps as a sign of their deepdevotion to Hinduism and as a way of underlining their own specific andeasily distinguishable style. Perhaps the greatest example of this new styleis the celebrated representation of Shiva as Nataraja (nata = dance, raja =king), seen by many as the quintessential image of the Chola. Based on an

6

Fig. 1Rajarajeshvara Temple,Tanjavur 2006Photo: John Millar

Fig. 2Temple car being drawnin procession by devoteesAnonymous, by a Tanjoreartistc.1800, gouache, 16.75 × 12in© The British Library

include the trishula (trident), the parashu (axe), which serves as the weaponthat conquers darkness and ignorance thus liberating man from the ties ofworldly matters, mriga (antelope) which in south India reflects his status asLord of Nature, agni (fire), symbolising destruction, a condition necessary forthe creation of new life, and damaru (drum), symbolising creation and alsoreferring to the god who resides in cremation grounds (the traditional Hindumethod of disposing of man’s earthly remains). (See key on p7)

Cat 3 Nataraja ‘Lord of Dance’ [see p16]

This is undoubtedly the most recognisable manifestation of Shiva and, asVidya Dehejia states in the exhibition catalogue, is ‘the quintessential deityof the Tamil country of south India’. Here Shiva is depicted within the ringof fire, the prabha, as both the creator and destroyer of the world, shownthrough the drum and the flame which can be seen in his two rear hands.His front hand left extends in a dance gesture and his front right hand is inthe abhaya position which indicates protection; this forms part of a dancerepresentative of the cyclical cosmic concept of time in India. Shiva can beseen standing on Mushalagan, the demon dwarf, who represents darknessand ignorance to be overcome. Shiva is shown with a serpent around hiswaist and flowing matted locks or dreadlocks (called jatamukuta), withinwhich can be seen Ganga, the goddess of the Ganges, another of Shiva’sconsorts. Once a celestial river, the gods granted that the river could flowon earth for the benefit of man. In order to break the fall of her descentShiva agreed to catch her in his hair.

Is any one symbol dominant in this representation of Shivaas Nataraja? Does the fact that Nataraja has four arms appearto give him extra powers, both of representation and of dexterity?

This sculpture seems to convey a sense of liberation and freedomdespite being encircled. How has the sculptor represented Shiva’senergy, expressiveness and carefreeness?

What role is the dwarf playing in the partnership with Shiva?Do you think the juxtaposition of the dwarf’s vanquished ignoranceand the supreme confidence of the god conveys a sense of harmonyor not? Why?

Tripuravijaya ‘Victor of the Three Cities’It was said that in return for their worship Shiva granted three powerfuldemons the right to live and rule over cities built of gold, silver and iron,located respectively in the heavens, in the air and on earth. For overa thousand years these demons resided in these cities increasing theirpower. Believing themselves to be invincible, since they could only jointly bedestroyed by a single arrow, they terrorised the world. Fearing the power ofthese demons, the gods and humans appealed to Shiva for help who, aidedby the gods, created a magical chariot and bow and arrow from the entireuniverse, destroyed all three cities with a single arrow, thus defeating thethree demons. The bow and arrow on this sculpture (bana-dhanus) are lost.

Somaskanda ‘Shiva with Uma and Skanda’ This manifestation of Shiva seated on a platform with his consort Uma(also known as Parvati) and their son Skanda (who, because he was so hot,

9

O Lord ShivaOn that day whenyou looked at me,you enslaved mein grace entered meand out of love meltedmy mind.SAINT MANIKKAVACHAKAR

The bronzes were placed in the temples,where they received ritual worship, whichincluded bathing, dressing and decorationwith jewels. It is important to recognise thatthese bronzes were not representations ofthe god or gods but were actual physicalembodiments of them and as such wereacknowledged as divine.

Today many of the bronzes have unusualpatinas (surface appearances) brought aboutby ageing. The surfaces are often pitted anddiscoloured which is in sharp contrast to theoften highly polished bronzes of those imagesthat are still worshipped in temples (fig. 4).This is normally because many of thesculptures were buried in order to escapetheir being captured by invading Muslimarmies. Sometimes sculptures were hidden within temples in speciallyconstructed secret compartments. The most famous cache of Chola bronzesculptures, discovered at Tiruvenkadu in the 1950s and now housed at theArt Museum in Tanjavur , is considered to be the finest of all Chola bronzes.Images which have seen long years of worship ordinarily have a very wornsurface due to the ritual bathing that they undergo in the temples. In orderto allow for the essential ritual of darshan to take place, the eyes are oftenre-cut because they have become worn away through continuous lustration.

The gods stand on lotus pedestals known as the padmapitha orpadmasana. These indicate the origin of all life, including that of the gods,and are among the most highly valued pedestals. The bronzes are rich withiconographic detail including pose, hair styles, hand gestures, ornamentationand attributes which are all imbued with meaning (see key on p7).

Shiva and his manifestationsThe origins of Shiva have long since been lost in the mists of time althoughit is certain that he cannot be traced back to any one single source. Thatsaid, it is thought that a number of elements attached to Shiva appear tooriginate with the Vedic wild god Rudra. Shiva is an unorthodox god,who delights in stepping outside of the norms of human behaviour andclearly relishes his outrageous conduct and moral ambivalence. With hischaracteristic dreadlocks he is both beautiful and unpredictable and theobject of intense devotion. He is known as Mahadeva (Great God),Nataraja (Lord of Dance), Mahakala (Great Black One) and Sundareshvara(Beautiful Lord).

Shiva is essentially found in two forms; aniconic, that is symbolisedwithout aiming at resemblance, and iconic, in which the god is represented.In respect to the aniconic form Shiva is represented as a linga, essentiallya phallic pillar, which in Shaivite temples is the central object of worship.Lingas can vary in size and each temple will have many lingas. The femaleequivalent of the linga is the yoni. Not surprisingly Shiva is representativeof fertility which is further enhanced with his association with snakes andNandi, his bull mount.

Shiva has a number of different manifestations in his iconic form, some ofwhich are included in this exhibition and indicated below. His main attributes

8

Fig. 4Ritual worship of ShivaNataraja and Parvati,Rajarajeshvara Temple,Tanjavur 2006Photo: John Millar

Fig. 3Temple car pulled throughthe Madras streets duringa festival1930sTopographical photograph12.7 × 10.2 cmPhoto: Klein and Peyerl© The British Library

of the Himalayas. Since Parvati has no great cult of her own, she is one ofthe manifestations of the third great Indian Hindu deity, the Great GoddessDevi, who has both benevolent and malevolent aspects and is accepted asthe fertile mother. Given both Shiva’s and Devi’s connection with fertility,Parvati is often seen as the male and female aspects of the same cult and,thereby, indivisible aspects of the same whole. Regarded as a goddess ofabundance, Parvati carries no weapons. Together, Shiva and Parvatirepresent the ideals of human physical love. Her vahana (mount) is the lion.

How do the contours of the fabric around Parvati’s legs enhancetheir form? Given that the sculpture is inanimate, what else dothe ripples of cloth suggest?

Examine the axis created by the figure. Which leg holds thevertical line and how is Parvati’s sense of strength affected by this?

Note the curvy line along Parvati’s pelvis and waistline whichcontinues into her bracelet. What does this suggests about Parvati?

SkandaGod of battle Skanda, seen in the Somaskanda group, is the son of Shivaand Parvati. Skanda’s vahana is the peacock, symbolic of immortality.

Cat. 14 Ganesha [see pp18 and 19]

The second son of Shiva and Parvati, Ganesha has an elephant head.Referred to as the Remover of Obstacles, he is also known when angeredas the Placer of Obstacles. It is said that Parvati became pregnant whilewashing dirt from her legs and gave birth to Ganesha in Shiva’s absence.Shiva returned home to discover a handsome youth guarding the entranceto Parvati’s bathroom where he was instructed to allow no-one to pass.Not recognising his father and Shiva not knowing who this presumptuousyouth was, the two began to fight. During their struggle Shiva cut offGanesha’s human head. When Parvati found out what had happened,she challenged Shiva who promised to bring the child back to life. Heordered his followers to bring him the head of the first being they meet,which happened to be an elephant. Restored to life, and as a form ofcompensation for what had happened, Shiva entrusted Ganesha with theleadership of his retinue of dwarves (the ganas), hence Ganesha ‘Lord of theGanas’. Ganesha is also custodian of doorways and thus is seen as Lord ofBeginnings. Ganesha is usually portrayed holding ankusha (elephant goad),used to distinguish spiritual movements and direct them, a pasha (noose),used to capture evil and ignorance, a bhikshapatra (bowl) representativeof the wandering aesetic or single laddu (type of Indian sweetmeat) anda broken tusk which he removed in order to use it as a pen when askedby the sage Vyasa to act as his scribe.

Although Ganesha’s body is rounded and elephantine, it is posedin the same shape as Parvati’s on page 17. What effect does thishave on the representation of Ganesha?

Why do you think Ganesha is one of the most popular Hindu gods?

11

was carried by Ganga and then the six Krittikas (Pleiades), who gave birthto him) is considered to be his main manifest form. According to the ShaivaSiddhanta philosophy, it is only when Shiva is in the company of Uma thathe can bestow grace upon an individual soul. This is the most popularbronze, as it can be used as a substitute in ceremonies for specificiconographies which the temple may not possess.

Vinaharamurti ‘Holder of the Vina (Lute)’ The vina is a seven-string instrument comprising a fret board with tworesonating hollow gourds at either end. Shiva’s front hands once playeda now missing instrument. His rear two hands hold an axe and an antelope.Shiva plays the vina in his manifestation as Dakshinamurti, Dispenserof Divine Wisdom.

Shrikantha ‘Lord of the Auspicious Neck’ This title refers to Shiva’s redeeming role as the imbiber of poison at the timeof the universal deluge of Hindu myth in which the earth and everything onit including the divine nectar of immortality and the lethal halahala poisonwere submerged. The story begins when Vishnu in his tortoise incarnation,Kurma, was involved in the creation myth when, like milk is churned to makebutter, the cosmic ocean was agitated to secure the nectar and hence secureimmortality for the gods. In order to do this the mountain Mandara was seton the back of Kurma and turned by the serpent Vasuki. The churning,however, released the halahala poison from the bottom of the sea, therebythreatening the world. Shiva was beseeched by the gods for his help andhe dove down into the waters, where he imbibed the poison, retaining itin his throat and thereby allowing the nectar of immortality to rise andsave the world.

Cat. 13 Vrishabhavana ‘Rider of the Bull’ [see p24]

In this manifestation, Shiva is shown leaning on Nandi, his bull mount,on the trishura (trident). The trident is Shiva’s most recognisable attribute.Although it appears to be a weapon, the trident is actually imbued withdeep philosophical meaning. Rather than as a weapon of violence, it is seenas a weapon of grace which is used to destroy the bonds that hold captivethe human soul. The prongs represent the three aspects of god as Creator,Protector and Destroyer. The long shaft represents the axis of the universe.As a whole, the trident can be seen, like a bolt of lightening, as a magicmeans of destroying demons. The iconography of the trident varies fromthe austere to the decorative, as seen in this example.

How does this representation of Shiva differ from the one onpages 4 and 5?

Shiva is a very active god. Do you think this scene portrays a momentof rest? What is the relationship between the god and the bull?

There are also a large number of deities and saints associated with Shiva.

Cat. 10 Parvati or Uma [see p17]

Shiva’s consort Parvati (referred to as Uma in the south of India), usuallyportrayed as a woman of great physical beauty, is considered to be a child

10

often shown without hair. She thenceforth became known as theMother of Karaikkal.

The sculptor has been asked to sculpt someone who has forfeitedbeauty. How has the artist done this? What has been taken awayto represent the absence of beauty?

Does this sculpture remind you of any modern sculptures?

Saint Manikkavachakar (lived in the second half of the ninth century)A minister to the Varaguna Pandya of Madurai, Manikkavachakar was sentto the west to purchase horses for the Pandya calvalry. En route, he cameacross Shiva disguised as a teacher. Manikkavachakar was so taken withthe teacher that he used the money intended for the horses to build atemple. The king, outraged by his behaviour, recalled his minister andimprisoned him twice. On both occasions Shiva intervened to secure hisrelease. Eventually he was permitted to join the teacher, Shiva, and hisfollowers. Manikkavachakar wrote a large body of poems.

Vishnu and his incarnationsVishnu has several characteristics which have evolved over the last thousandyears and probably has more devotees than either Shiva or Devi. Vishnu hasten avatars or bodily incarnations, which are Matsya (fish), Kurma (turtle),Varaha (boar), Narasimha (lion), Vamana (dwarf), Parasurama, Rama,Krishna, Buddha and Kalki (an incarnation which is yet to manifest itself).

Vishnu, seen as the preserver and maintainer of established order, holdssway over intervening time (that is, the time not ruled by Shiva as Lord ofthe Beginning and Lord of the End). Known for avoiding extremes, unlikeShiva, Vishnu is seen as maintaining orthodox standards, placing his strongbelief in the family and caste system above the good of the individual.As such, Vishnu is regarded as the god of accepted behaviour and the homeas well as of love and emotion. Vishnu became increasingly popular duringthe time of the Mughals, when the power of Hinduism was challenged byIslam in India. His most popular cults since the fifteenth to sixteenth centurieshave been Rama and Krishna, who are discussed below.

Vishnu is normally seen wearing a crown reflecting his regal qualityand carrying a sankha (conch shell), whose sound wards off demons andwhose spiralling is symbolic of infinite space and padma (lotus flower)symbol of beauty, happiness and eternal renewal. His distinctive weaponsare the gada (club) which provides protection and represents the powerof natural laws and time and chakra (discus), the symbol of the cycle oflife and death.

Bhu-VarahaBhu-Varaha embraces goddess earth Prithivi, who had been abducted bya demon and hidden at the bottom of the ocean. Varaha defeats the demonand rescues Prithivi and makes her habitable for living creatures by creatingthe continents and mountains.

Cat. 22 Yoga Narasimha [see p21]

The man-lion Narasimha vanquishes a gatekeeper, Hiranyakasipu, whomhe had condemned to live as a demon. Granted special powers by Brahma,

13

Nandi the bull, the vahana of Shiva, is associated with Shiva because ofhis strength and fertility. At Shiva temples, Nandi is placed between thecourtyard and the temple, where he marks the entrance and sits facingthe inner shrine where the linga is located.

There are a number of saints associated with Shiva. These are referredto as the nayanmars and total sixty-three, not including the ninth-centurysaint Manikkavachakar. These saints lived between the sixth and earlyninth centuries and helped make up a community of holy people whotravelled across the Tamil countryside as part of a popularising movementcalled bhakti. These saints would stop at each temple to sing the gloriesof the enshrined deity. Referring to themselves as adiyar or tontar, slavesor servants of Shiva, they composed around seven hundred hymns knowncollectively as Tevaram. Stone representations of all sixty-three nayanmarsare usually found in Shaivite temples.

Saint Sambandar (probably lived in the second half of the seventh century)Sambandar often accompanied his Brahmin father to the temple in Sirkali.One day the father left his son on the steps of the temple tank as he tookhis ritual dip. Sambandar was hungry and began to cry. When his fatherreturned he found the child playing with a golden cup with milk runningdown his chin. When the father asked his son where the milk came from,Sambandar pointed to the temple tower where there was a representationof Uma seated next to Shiva and began singing a song praising the divinecouple. Saint Sambandar is often shown holding a cup in one hand andpointing with the other. As a lover of music and composer of verses heis often depicted dancing.

Saint Chandesha (also known as Chandeshvara)The young Chandesha, a cowherd, used to lustrate a mud linga that heworshipped with milk. His father, concerned with this misuse of milk, cameout one day to see what his son was doing. Oblivious to his father’s presenceand his angry words, Chandesha remained deep in devotion to Shiva. Hisfather was so enraged by his behaviour that he kicked out at the mud lingacausing Chandesha to lash out with his staff knocking his father to theground. On witnessing this, Shiva and Uma appeared to Chandesha andblessed him with a divine garland. Chandesha is usually shown with hishands joined in a position of worship, anjali.

Cat. 17 Saint Karaikkal Ammaiyar (lived in the sixth century) [see p20]

A beautiful young woman called Punitavati and her husbandParamadatta, a trader in Karaikkal, were both devotees of Shiva. Oneday Paramadatta sent home two mangoes which he instructed were tobe served as part of his lunch. Before he returned home, Punitavati gaveone to a sage who appeared at their door begging for food. While havinghis lunch, Paramadatta ate one of the mangoes and asked for the other.At that moment Punitavati thought of Shiva and a mango appeared inher hand, although it differed from the two that her husband had senthome. On realising this, Paramadatta asked where it had come from and,not believing his wife’s reply, reached out for it, only for it to disappear.Perceiving his wife to be divine, Paramadatta left the family home onlyto return to worship her. Punitavati appealed to Shiva to take away herbeauty so that she could devote herself to his worship. As a result herbeauty disappeared and she became an emaciated old woman who is

12

Krishna can also be seen in the family group which is a rare exampleof a familial group created by the same artist or workshop. Krishna isaccompanied by two of his consorts Rukmini and Satyabhama and hismount, the divine eagle Garuda, king of birds and symbolic of the windand sun, is able to move at the speed of light.

This sculpture of Krishna is one of the biggest and most importantChola bronzes in a Western collection. Made of solid bronze, it mustbe extremely heavy. How has the sculptor conveyed lightness?

The medium of dance is vital to Indian culture. Do you think the ideaof dance been incorporated into this sculpture? How?

ConclusionThere can be little doubt that the Cholas had a major impact on thedevelopment of culture across southern India. Although the dynasty onlylasted some four hundred years, it left a lasting and highly visible legacythroughout the region. The Cholas influence is most tangible through thenumerous temple complexes that they built and the corpus of magnificentbronze sculpture, the like of which many would argue has never beenequalled. In promoting the cult of Shiva Nataraja, the Chola also createdone of the most recognisable, widely used and enduring symbols, whichhas come to epitomise India.

15

They trembled the gopis and gopas.He climbed uponthe flowering bluekatampa oak,he dived into the waters,danced on captive Kaliya.

which meant that he could not be injured by any weapon wielded by manor animal, day or night, inside or outside, the demon began to create manyproblems for the gods. Assuming the head of a lion and thus appearing asneither man or animal, Yoga Narasimha hid in a pillar at the entrance to thehouse of the demon and grabbing him at dusk (neither night nor day) andon the threshold of his house (neither inside nor outside) Yoga Narasimhamauled the demon with his claws (that is without weapons) and thusdefeated Hiranyakasipu.

Thinking of Narasimha’s story and the way he conquered the demon,do you think he seems wise? How has the sculptor conveyed a senseof wisdom or authority?

Can you see any evidence in this sculpture of the machinery involvedin taking it on procession?

Rama Rama is the great hero of the Hindu epic, the Ramayana, which recounts theadventures he undergoes after being exiled to the forest by his father, kingDasharatha to fulfil a promise made to his youngest queen. Rama is exiledwith his wife Sita and his brother Lakshmana. Sita, seen as a model wife forfollowing her husband into exile, is left unguarded in the forest. Abducted bythe demon king Ravana, Sita is taken to the island of Lanka (Sri or Shri is aSanskrit term of respect meaning illuminated one). Rama, suspecting Sita’schastity, rejects her, berating himself for allowing the situation to happen.Accompanying Rama is the monkey general Hanuman (Cat. 24) who locatesSita and leaps across the sea to the island of Lanka to give her a messagefrom Rama. Hanuman then returns to join Rama in victorious battle againstRavana’s army. Rama is adored because he is a human hero who is also divineand the epic emphasises this fact since Ravana could not be killed by godsor demons but, in his arrogance, had not sought the same protection fromman. Today Rama and Sita have come to symbolise incorruptibility, honesty,loyalty and tenderness.

How has Hanuman been portrayed to suggest that he is a monkey?

Can you describe Hanuman’s character from looking at this sculpture?

Cat 25 Krishna [see p23]

This is considered to be the most important incarnation of Vishnu, andKrishna is revered as a god in his own right. Krishna means ‘the black one’although he is often portrayed with blue skin. It is said that Vishnu pluckedtwo hairs from his head, one white and one black, which impregnated Rohiniand Devaki. Two brothers were born; Balarama from the white hair andKrishna from the black. Here Krishna is seen dancing on Kaliya. This rareiconography represents one of the many heroic feats performed by Krishnaas a youth. Kaliya, the serpent demon, lived in the river Jumna with hisserpent queens. Krishna dove into the river to do battle with Kaliya.Victorious Krishna spared Kaliya on account of the pleas of his serpentqueens but only after the serpent demon promised to change his ways.Krishna is shown dancing triumphantly on the hood of Kaliya symbolicof his victory.

14

‘You who are the mostancient supreme being,they call you the best body

and the supremeBrahma, the highest yogaand the most excellentspeech,

the supreme mystery,and the highest path.’NAMMALVAR TIRUVAYMOLI

‘In leaping I shall makethe mountains tremble,leaping monkeys.

And as I leap the sea,the force of my thighswill carry along the

blossoms of vines, shrubsand trees on every side.

They will follow behindme as I leap through thesky this very day,

so that my path willresemble the Milky Wayin the heavens …’VALMIKI RAMAYANA

Cat. 2 [p16]Shiva as Nataraja (Lord of Dance)c.1100, bronze, 86 × 107 cmGovernment Museum, ChennaiPhoto Aditya Arya Photography

Cat. 10 [p17]Devi Uma Parameshvari(Great Goddess Uma)c.1012, bronze, height 88.9 cmAsia Society, New York, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd, 1979.19Photo Lynton Gardiner

Cat. 14 [pp18 and 19]Ganeshac.1070, bronze, height 50.2 cmThe Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift ofKatharine Holden Thayer, 1970.62Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Katharine Holden Thayer 1970.62

Cat. 17 [p20]Saint Karaikkal AmmaiyarTwelfth century, copper alloy, 23.2 × 16.5 cmThe Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,Purchase, Edward J. Gallagher, Jr., Bequest, inmemory of his father, Edward Joseph Gallagher,his mother Ann Hay Gallagher, and his son,Edward Joseph Gallagher III, 1982 (1982.220.11)Photo © 1994 The Metropolitan Museum of Art,New York / Bruce White

Cat. 22 [p21]Yoga Narasimhac.1250, bronze, height 55.2 cmThe Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. Norman Zaworski, 1973.187Photo © The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Dr. Norman Zaworski, 1973.187

Cat. 24 [p22]Monkey General HanumanBronze, height 41 cmVictoria and Albert Museum,Bequest of Lord CurzonPhoto V & A Images/Victoria and Albert Museum

Cat. 25 [p23]Krishna Dancing on KaliyaEleventh century, bronze, height 87.6 cmAsia Society, New York, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd, 1979.22Photo Lynton Gardiner

Cat. 13 [p24]Trident with Shiva as Vrishabhavana(Rider of the Bull)c.950, bronze, height 83.5 cmThe British Museum, LondonPhoto © Copyright the Trusteesof The British Museum

1716

18 19

2120

2322

Bibliography and further reading

BLURTON, T. RICHARD

Hindu Art(2001, The British Museum Press, London)

DALLAPICCOLA, ANNA

Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend(2002, Thames and Hudson, London)

DALLAPICCOLA, ANNA

Hindu Myths(2203, British Museum Press, London)

DEHEJIA, VIDYA

Art of the Imperial Cholas (1990, Columbia University Press, New York)

DEHEJIA, VIDYA ET AL

The Sensuous and the Sacred: Chola Bronzes From South India(2002, American Federation of Arts in associationwith the University of Washington Press, Seattle)

DEHEJIA, VIDYA ET AL

Chola: Sacred Bronzes from Southern India(2006, Royal Academy of Arts, London)

JANSEN, EVA RUDY

The Book of Hindu Imagery: The Gods and their Symbols(1993, Binkey Kok Publications BV, Havelte)

MICHELL, GEORGES

Hindu Art and Architecture(2000, Thames & Hudson, London)

NARAYANAN, VASUDHA

Understanding Hinduism (2004, Duncan Baird, London)

WOOD, MICHAEL

The Smile of Murugan: A South Indian Journey(1996, Penguin, Harmondsworth)

ZAEHNER, R.C., Hinduism(1962, Oxford University Press, Oxford)

24