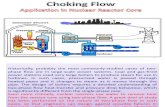

Choking in adults

Transcript of Choking in adults

Choking, also described as foreign body airway obstruction (FBAO), is a preventable cause of accidental death in adults (Perkins et al., 2015). Its exact prevalence is unknown, as most episodes are managed without resort to healthcare services; however, it is known to be common. In London, UK, alone, an ambulance was called to a choking incident an average of five times a day during 2016 (Pavitt et al., 2017a). Most episodes of choking are dealt with successfully, however deaths do occur. According to statistics for England and Wales, choking contributed to the deaths of 398 people in 2017; the majority were over the age of 60 years (Office for National Statistics, 2018). Aside from age, risk factors for choking include reduced consciousness, drug or alcohol intoxication, and impaired airway reflexes following neurological injury (Wong & Tariq, 2011). In adults, most episodes occur during eating or drinking.

Early recognition and intervention are the keys to successful management of choking incidents (Jevon, 2018). In mild choking, encouraging coughing and monitoring for deterioration are all that is required (Simpson, 2016). In severe choking, simple interventions including back blows, abdominal thrusts and chest thrusts can relieve the obstruction, and prevent the development of severe hypoxia and loss of consciousness. A combination of techniques is required in 50 per cent of cases (Perkins et al., 2015). If intervention is unsuccessful in severe airway obstruction, collapse and cardiac arrest rapidly ensue. If this occurs, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be started, and emergency services must be called (NHS, 2018). Following successful treatment, individuals should be assessed for residual material in the airway, and sent for medical assessment if this is suspected (Jevon, 2018). They will also need assessment following abdominal thrusts or chest compressions.

These pages describe the assessment of an adult who appears to be choking, outline emergency management techniques, and identify key aspects of post-choking care. The management of choking in infants and children is covered in a separate procedure. Refer also to the clinicalskills.net procedures on cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults, as required. Clinicians should recognise their own limitations in managing the choking adult, and seek senior support and advice early when dealing with this life-threatening event.

Page 1 of 4

Kitchen

NOCHILDRENALLOWED

IN THEKITCHEN

THANKYOU!

Fire doorkeepshut

WATERFIRE EXT INGUI SHER

H OLDUPRIGHT

PULLOUTPIN

A IM AT BASEOF

F IREF ROMA

D ISTAM]N CE1MET RE

S QU EEZ E LEVER

P AS SE DC ON DUC TIVI TYO FD IS C HAR GE

Adults

Choking in adultsDemonstrated by Michael Sampson, Senior Lecturer, London South Bank University

©2020 Clinical Skills Limited. All rights reserved

In adults, most choking incidents occur during eating (Pavitt et al., 2017a). Although food is the most common culprit, other items that cause choking in adults include dentures, hat or scarf pins, and pen lids. Elderly people are at greatest risk, as are those with a reduced level of consciousness (Perkins et al., 2015). Other risk factors for choking include drug or alcohol intoxication; impaired swallow or cough reflexes, for example after a stroke; respiratory disease and respiratory failure; poor dentition; and dementia (Wong & Tariq, 2011)

Do not undertake or attempt any procedure unless you are, or have supervision from, a properly trained, experienced and competent person.Always first explain the procedure to the patient and obtain their consent, in line with the policies of your employer or educational institution.

Ask the person “Are you choking?” (Perkins et al., 2016). If they have a strong cough, and are able to speak and breathe, the airway obstruction is mild; offer support as required (see next page). If their cough is weak, they are unable to speak, or they are struggling to breathe, the obstruction is severe and physical intervention is necessary; see next page (Jevon, 2018).

Recognition Assessment

Oxygen

20 0 0m l

15 0 0m l

100 0m l

500m l

OFF

CPINK OR DISCOLOURED

NPIPELINE PROTECTORO PART

EQUIPMENT LTD (017052270)

HIGH

SUCTION

-kPa

60

-100 0

40

80 20

750

-mmHg

625

500

250

125

375

PEPP

ER

Risk factors

Suspect choking if an individual develops a persistent cough during or after eating, or becomes suddenly distressed or breathless (Simpson, 2016). Other signs of choking including clutching at the neck, and trying to attract attention by waving the hands. The person may appear red in the face. If the airway obstruction is severe, they may be unable to speak.

Management ofMedical Emergencies

Umbilicus

Xiphoid

x 5

Adults

Choking in adults Page 2

Mild airway obstruction Severe airway obstruction

Delivering abdominal thrusts: (a)

Physical intervention can worsen mild airway obstruction, so take a simple, supportive approach (Perkins et al., 2015). Encourage the person to keep coughing, and be ready to act if their condition deteriorates. Continue monitoring them until the obstruction is cleared. If the person’s cough becomes weak and ineffective, they become unable to speak, or they start to struggle for breath, treat them for severe airway obstruction (Simpson, 2016).

In severe airway obstruction, you will have to use physical manoeuvres to clear the airway (Jevon, 2018). Start with back blows. Stand behind the person and slightly to one side. Support their chest with your non-dominant hand, and lean them forward so that any dislodged material will come out of their mouth and not fall back into the airway (Perkins et al., 2015). They will be frightened; tell them what you are doing, and give reassurance.

As soon as you are ready, strike them firmly between the shoulder blades with the heel of your free hand and check for effect (Simpson, 2016). Deliver up to five back blows. If this does not clear the obstruction, move on to abdominal thrusts, unless the individual is pregnant or too obese for the technique to be effective, in which case use chest thrusts as shown on page 3 (Perkins et al., 2015).

Stand behind the person and put both arms around the upper abdomen. Lean the person forward. Place a clenched fist between their umbilicus (belly button) and the bottom of their rib cage (Jevon, 2018). Grasp your fist firmly with your other hand. Make sure that your head is not directly behind the victim’s, otherwise their head may fly back and hit you in the face during delivery of the manoeuvre. Tell the person what you are doing and reassure them.

Page 2 of 4

Do not undertake or attempt any procedure unless you are, or have supervision from, a properly trained, experienced and competent person.Always first explain the procedure to the patient and obtain their consent, in line with the policies of your employer or educational institution.

As soon as you are ready, pull sharply inwards and upwards, driving your fist into the person’s abdomen (Perkins et al., 2015). This generates considerable intra-abdominal pressure, and may dislodge the obstruction (Pavitt et al., 2017b).

Give up to five abdominal thrusts, checking to see if the airway has been cleared after each thrust. If the airway is still obstructed after five thrusts, return to back blows. Alternate five back blows and five abdominal thrusts until the obstruction is cleared, or the person loses consciousness.

x 5 x 5

Management ofMedical Emergencies

(b)

Abdominal thrustsDelivering back blows

Adults

Choking in adults Page 3

In obese people, you may not be able to get your arms around the abdomen well enough to deliver effective abdominal thrusts.

Do not use abdominal thrusts on a pregnant woman as this could harm the fetus (Simpson, 2016).

In these situations, use chest thrusts instead of abdominal thrusts (Perkins et al., 2015). Stand behind the person and wrap both arms around their chest. Place a clenched fist in the centre of their chest, grasp it with your other hand, and pull sharply inwards.

Give up to five chest thrusts; if this does not clear the obstruction, return to back blows (Simpson, 2016).

Alternate five back blows ... ...and five chest thrusts until the obstruction is cleared, or the person loses consciousness.

Page 3 of 4

Do not undertake or attempt any procedure unless you are, or have supervision from, a properly trained, experienced and competent person.Always first explain the procedure to the patient and obtain their consent, in line with the policies of your employer or educational institution.

Management ofMedical Emergencies

Fire doorkeepshut

PUSH

Fire doorkeepshut

PUSH

x 5 x 5

x 5

Pregnancy and obesity: chest thrusts (a) (b)

(e) (f)

(c) (d)

Floor is curved and/or tilting

x 30

If possible quickly put on gloves

Adults

If physical manoeuvres fail to clear the obstruction, the person will lose consciousness due to hypoxia (Simpson, 2016). Carefully lower them to the floor, and turn them onto their back. In a hospital setting, ask a colleague to call the cardiac arrest team by dialing 2222. Outside of hospital, ask a bystander to call 999 or do it yourself. Start CPR with chest compressions as soon as possible (Perkins et al., 2015). Give 30 chest compressions...

...and then attempt two rescue breaths; continue CPR until the person starts to breathe normally, or expert help arrives and you are asked to stop. Refer to the clinicalskills.net procedures on cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

After successful treatment of choking, some foreign material may remain in the airway (Wong & Tariq, 2011). The person may have a persistent cough, difficulty swallowing, or feel that something is stuck in their throat. If this occurs, arrange urgent medical assessment or send them to the Emergency Department (Perkins et al., 2015).

Further investigations may include chest X-ray and bronchoscopy. Removal of residual material from the airway can prevent the development of complications such as pneumonia or abscess formation (Rodríguez et al., 2012).

Page 4 of 4

Do not undertake or attempt any procedure unless you are, or have supervision from, a properly trained, experienced and competent person.Always first explain the procedure to the patient and obtain their consent, in line with the policies of your employer or educational institution.

If the choking incident occurs while the individual is in a healthcare setting, or receiving care from a health professional in their own home, document it in their notes or electronic patient record. Inform the patient’s medical team or general practitioner, and complete an incident form if this is local policy. If there are medical factors that may have contributed to the incident, for example swallowing difficulties, consider a formal assessment, changes to diet and referral to a speech and language therapist (Thompson, 2017).

Although abdominal thrusts and chest thrusts are life-saving techniques, they can cause internal injury (Simpson, 2016). Arrange urgent medical assessment for any person who has received abdominal or chest thrusts, or send them to the emergency department. There is an increased risk of internal bleeding in people taking anticoagulant or anti-platelet drugs; there should be a low threshold for sending these individuals for a thoracoabdominal CT scan (Perkins et al., 2015).

Choking in adults Page 4

Management ofMedical Emergencies

Patient Notes ? X

OK Cancel

General Notes

Patient choked on a piece of chicken during lunch. Inadequate cough but remained conscious.

Obstruction cleared with a single back blow.

Observations post-choking within normal parameters, saturating 98% on room air with no evidence of residual obstruction.

Awaiting review by medical team.

Allergy Notes

Oxygen

15

10

5

1

OXY

GEN

per M

INU

TELI

TRES

15

10

OXY

GEN

LITR

ESpe

rMIN

UTE

5

1

o2o2

2O 2O

1

3

2

2Face Shield

x 2

Loss of consciousness: (a) start CPR (b)

Internal injury (a)

(b) Documentation

Aftercare