Chinese calligraphy 1

-

Upload

anita-welych -

Category

Art & Photos

-

view

363 -

download

3

Transcript of Chinese calligraphy 1

Chinese Dynasties ca. 2100 – 1600 BC Xia Dynasty: (ink made; bronze cas>ng) ca. 1600 – 1050 BC Shang Dynasty Ca. 1046 – 256 BCE Zhou Dynasty (Scythian influence!) Ca. 221 – 206 BCE Qin Dynasty (TerracoLa Army; Great Wall) 206 BCE – 220 AD Han Dynasty (jewelry, figure pain>ng, celadon) 220 – 589 AD Six Dynas>es Period (landscape pain>ng) 581 – 618 AD Sui Dynasty 618 – 906 AD Tang Dynasty (porcelain, pain>ng, woodcut) 907 – 960 AD Five Dynas>es Period 960 – 1279 AD Song Dynasty (porcelain, movable type 1041) 1279 – 1368 AD Yuan Dynasty 1368 – 1644 AD Ming Dynasty (blue-‐white porcelain, enamel) 1644 – 1912 AD Qing Dynasty 1912 – 1949 AD Republic Period 1949 – present People’s Republic of China (Ai Wei Wei)

Chinese Calligraphy

• Ini>ally characters – pictograms – were incised into bone or clay that was later cast in bronze.

• As characters developed and became more regular, around 300 BC the brush was invented and used on silk. Shortly thereafer, paper was invented (for toilet paper!!!) and became the primary support for wriLen expression.

• The brush has certain quali>es that make wri>ng look dis>nct from carving or incising.

Materials: “The Four Treasures”

• Wri>ng brush – invented ca. 300 BCE • Inks>ck – Chinese ink comes in solid form, made of soot (tradi>onally from an oil lamp, later from pine soot, mixed with animal glue (tradi>onally deer)

• Paper – made from inner bark of mulberry tree, hemp or bamboo; invented ca. 300 BCE

• Inkstone – used to both grind the solid ink into liquid and as wet ink container

• Right, inkstone and holder, early 18th century, Qing dynasty

• Lef, brush holder, early 17th century, Ming dynasty

The tools of the trade

Oracle Bone Style

• Chinese wriLen language began to develop ca. 1000 BCE

• Earliest form: pictographs, scored into surfaces of jades and oracle bones.

• Shang dynasty oracle bones

Seal Script • Ofen used for official inscrip>ons on stone monuments and seals

• Thin, even lines executed with balanced movements.

• Developed during Shang and Zhou dynas>es.

• “Direct parent” of modern Chinese

script

Lishu or clerical script

• Developed ca. 500 BCE, common in Qin and Han dynas>es. Used for official records, monuments and private correspondence.

• First script widely created with brushwork – more flowing style

• Shape of Lishu characters iden>cal to modern Chinese characters.

• Heng Fang Stele, Han Dynasty

Kaishu or “standard” script • Appeared ca. 220 AD during Han dynasty • Essen>ally the tradi>onal script used today • Similar to Lishu but more cursive, containing serif-‐type elements at the

end of strokes

“Thousand Character Classic” in Standard and Cursive Scripts Zhiyong, 7th genera>on Descendant of famed Calligrapher Wang Xizhi. Ca. 510 – 610 AD, Sui Dynasty

Xingshu or “running” script

• “semi-‐cursive” script allows for characters to be aLached to each other. Natural progression of using a supple tool.

• Considered more abstract, beau>ful and expressive than Lishu, but s>ll highly prac>cal for wri>ng.

• Wang Xizhi, “Preface to the Orchid Pavilion” 353 AD

Emperor Song Huizong, The Five-Colored Parakeet, Song Dynasty

• Calligraphic style known as “slender gold”

Cao shu or “grass script”

• Without training, this script cannot be read • En>re characters may be wriLen without lifing the brush from paper at all.

• Strokes are modified or eliminated to facilitate smooth wri>ng

• Characters are rounded and sof in appearance, lacking angular lines.

• Aesthe>c and expressive concerns dominate over communica>on.

“Autobiography of Huai Sui”, Tang Dynasty, ca. 737 - 777

• Example of kuangcao or “wild cursive” script • Younger buddy of Zhang Xu, who were together known as “Crazy Zhang and Drunk Su” – famed in their day for being equally brilliant and disorderly

Zhang Xu, 8th century

• Gushi Si>e, Tang Dynasty • Zhang Xu always finished

work in a single siong • Unpredictable yet bold

and beau>ful • It was said that he and the

younger Huai Su would get drunk together and work un>l they passed out.

• Presumably he some>mes used his own hair as a brush!

• Nonetheless, Zhang Xu also mastered regular script and was revered in his >me for his brilliance.

Biographies of Lian Po and Lin Xiangru, by Huang Tingjian, ca.

1095

• Appx. 13 “ x 60 feet, inspired by Huai Su’s autobiography

• Similari>es and differences?

• What type of script do you think each represents?

Li Zhan’gang, 2009

Wen Peng, 1498 -‐ 1573

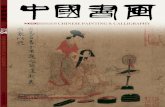

Chinese Pain>ng • Closely linked to calligraphy • One of “The Three Perfec>ons” along with poetry and calligraphy

• For Chinese ar>sts, the point is to depict the ESSENCE of the subject, rather than just the LIKENESS.

• Main techniques: Gong-‐bi “me>culous” – detailed, usually colored and figural subjects

• Shui-‐mo (Japanese: sumi-‐e) “water-‐ink” pain>ng, da>ng to Tang dynasty.

• Wen-‐jen-‐hua “litera>” pain>ng – self-‐expression and crea>vity, introduced during Song dynasty

Mi Fu: poet, calligrapher, painter 1052 – 1107 (Song Dynasty)

• First to use calligraphic techniques in pain>ng • Valued historic styles, collec>ng historic examples of

calligraphy, which he copied and mastered. • While fas>dious (probably OCD), he was also eccentric,

preferring clothes of ancient dynas>es and obsessively collec>ng stones.

• Above all, ar>s>cally he value spontaneity and self-‐expression.

• His handling of the brush was described as “like a sharp sword handled skillfully in fight, or a bow which could shoot an arrow … piercing anything that might be in its way.” U>lized Xingshu (running script) and Caoshu (cursive)

• With other intellectuals, rediscovered key Tang painters and formulated the theory and prac>ceof crea>ve self-‐expression, known as wen-‐jua-‐hen.