Chief - Sybaris Bistrosalt (if preserved). Avoid wild grape leaves (Vitis californica), which...

Transcript of Chief - Sybaris Bistrosalt (if preserved). Avoid wild grape leaves (Vitis californica), which...

1 8 january/february 2012 | Northwest Palate | est. 1987 w w w. N o rt h w e st Palate . com

Chef Matt Bennett of Sybaris restaurantin Albany, Oregon, went on a culinary

journey, learning about Native American

cuisine and landing at the James Beard House

in New York, where he prepared a menu

inspired by indigenous foods of the Pacific

Northwest and the food traditions of Oregon’s

Kalapuya tribe. ChiefChiefChiefChef

By Bonnie HendersonPhotos By Krishna Dayanidhi

JF12_FINAL.indd 18 12/22/11 11:45 AM

1 8 january/february 2012 | Northwest Palate | est. 1987 est. 1987 | Northwest Palate | january/february 2012 1 9 w w w. N o rt h w e st Palate . com

t’s four hours to dinnertime at the James Beard House in New York’s Greenwich Village, and chef Matt Bennett of Sybaris restaurant in Albany, Oregon, is hunched over a

slender smoked eel, painstakingly peeling off the skin. At the other end of the butcher-block countertop are arrayed dozens of veiny, star-shaped wild salmonberry leaves, the tips curling up as they thaw after the flight from Oregon. Bennett is using them in place of the banana leaves or cornhusks normally used to wrap tamales.

For this dinner—a celebration of the foods of Oregon’s native Kalapuya people, re-imagined by Bennett for contemporary pal-ates—the tamale dough includes acorn flour, and the filling is quail confit. Standing expec-tantly alongside the leaf-strewn countertop

are three young women in crisp white toques and white double-breasted jackets, students from New York culinary schools volunteering for the afternoon. Bennett breaks from his work on the smoked eel and foie gras appetiz-ers to put the students to work.

“Have you ever made regular tamales before?” he asks. The students glance at one another, then all three shake their heads no, smiling apologetically. Bennett pauses, nods, smiles back. “Well, here’s how you do it,” he says, reaching for an ice cream scoop.

There are dishes, techniques, ingredients you don’t necessarily learn in cooking school. Some you can learn from written recipes. Others may emerge out of friendships, or travel, or a passion for history, or an instinct to help others. Bennett’s repertoire and his

restaurant’s menus have been informed by all of the above—sometimes all at the same time.

Take tamales, for instance. Bennett and his wife, Janel, had become regulars at a little family-run Oaxacan restaurant in Albany that was struggling to stay open across the tracks—literally—from Sybaris. “We said to Willi, let’s do a lunch together and see if we can turn on some of our customers to your food,” Bennett recalls. Which is how, at Willivaldo Guzman’s elbow, Bennett learned how to make Oaxacan pork tamales, to beat the chilled masa a second time to give it that fluffy mouthfeel emblematic of the best tamales.

Then there was the Pakistani lunch served at Sybaris and cooked, under Bennett’s watch-ful eye, entirely by his friend Mohammed Ahmed, an aviation industry executive. “Mo

is a friend of ours and a really, really good cook,” Bennett says. “He’d always wanted to have his own restaurant.” But Ahmed’s Pakistani family wouldn’t hear of him becom-ing a chef. It was, they felt, not a legitimate career for someone of his social class. So Bennett offered the Sybaris kitchen and clien-tele to Ahmed for a day. “He brought the odd ingredients: fenugreek, black caraway seeds,” Bennett says. “We helped plate the meal. But he was the chef.” And Bennett, in the process, learned how to flavor 15 pounds of tenderloin with a pound each of cumin and coriander and still end up with a delicately nuanced dish. Variations of some of Ahmed’s dishes—lamb tikka, and for dessert, kulfi—now peri-odically appear on the menu at Sybaris.

The story of the Kalapuya-inspired meal

began one year ago, when Bennett learned of local efforts to preserve a natural area on the north side of Albany and build a nature center named for the tribe native to the Willamette Valley. Bennett decided to con-tribute in his usual way, by hosting a benefit dinner at Sybaris. He knew right away that he wanted to showcase the traditional foods of the Kalapuya people. Now Bennett—native to the Detroit suburbs, his ancestry Anglo-Gallic, his culinary training classically French—just needed to learn what those foods were.

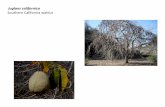

He began by talking with the forager who supplies Sybaris with wild edibles. Then he contacted a local naturalist who, it turned out, was a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Grande Ronde, of which the Kalapuya tribe is one. The Tribes’ cultural

department sent Bennett a list of traditional foods, and the menu began taking shape: a series of dishes that incorporated camas, nettles, acorns, wapato, venison, steelhead, and quail, but in new renderings.

Based on the overwhelming positive response to the benefit dinner held in April, Bennett was urged to propose the Kalapuya menu to the Beard House, where Bennett had cooked once before in 2008.

The Beard House staff greeted the idea with cautious enthusiasm. No chef at the Beard House had ever attempted a meal quite like this—an homage to one Native American tribe’s food traditions, incorporat-ing dozens of wild foodstuffs, many of them unique to that region, flown in with the chef and his staff. But what cinched it was its

Hot and Cold–Smoked Steelhead Trout

with Camas Bulb Cake and Yerba Buena Crème Fraîche

“We didn’t eat food like this. But I wish we had!”

Grande Ronde Tribal Council member Kathleen Tom

JF12_FINAL.indd 19 12/22/11 11:45 AM

2 0 january/february 2012 | Northwest Palate | est. 1987 w w w. N o rt h w e st Palate . com

uniqueness, says Izabela Wojcik, director of programming at the James Beard House. “What Matt is doing is examining the prepa-rations and trying to bridge the gap between how those native people would have cooked and how a chef today cooks, figuring out how to make it appealing to a contemporary diner. This is not a historical meal.”

But it was a meal that required plenty of research on Matt’s part. He learned from tribe members that camas had been a staple food—the main source of carbohydrates—of the Kalapuya people, who baked the bulbs in earthen ovens. Slow-cooking in a Crock-Pot, Bennett discovered, produces similar results. Nettles, which appeared on the menu in the form of crackers, needed to be gathered in the spring as tender shoots and then blanched (to remove the sting) and frozen. The September dinner in New York—a refinement of what Bennett served in Albany in April—required months of preparation and procuring, as certain foods could only be dug, picked, or gathered in season.

In the process, Bennett became a culinary champion of the Confederated Tribes—and they of him. Terminated by the government in 1954, the tribes managed to regain fed-eral recognition in 1983. The success of their casino has since made their Spirit Mountain Community Fund—which helped Bennett take the Kalapuya menu to New York—the tenth largest charitable foundation in Oregon.

Selling out the dinner was no problem, thanks perhaps to world-weary New Yorkers’ hunger for something completely different. Bennett’s selection, CONTINUEd ON PAGE 22

Quail tamalesmakes 6 small tamales

For the Beard House dinner, chef Bennett prepared quail confit—a multi-day process—and he used acorn flour (available in Asian food stores) for part of the corn masa. The following recipe is a simpler version for home cooks.

•3quail•Salt•1quartcoldwater•1/2cupsourcream•2cupsmasafortamales•1tablespoonbakingpowder•1/4cupduckfatorlard,atroom

temperature•6salmonberryleaves*

Lightly salt quail and chill overnight. The next day, place quail in cold water, bring to a simmer and poach the quail for about 30 minutes, or until cooked through but still very tender. Remove quail and reserve two cups of poaching broth. Pick all of the meat off the bones. Discard skin, gristle and bones. Mix quail meat with sour cream and set aside in the refrigerator. Mix masa and baking powder with a paddle attachment of a kitchen mixer. Set mixer at low speed and add the two cups of reserved warm broth. Increase speed to medium and add the fat. Taste for seasoning. Chill the (now soft) mixture until firm, about an hour. Prepare a steamer. Lay out six leaves on the counter. Return the chilled masa to the mixer and beat again at medium speed until light; correct season-ing. Divide the masa among the six leaves. Divide the quail into even portions and nestle a mound into the masa on each leaf. Fold the leaves tips in and place in the steamer, seam side down. Steam for 45 minutes or until firm. *Salmonberry leaves (Rubus spectabilis) may be picked and used fresh spring through fall. May substitute cultivated grape leaves, well rinsed to remove any pesticides (if fresh) or excess salt (if preserved). Avoid wild grape leaves (Vitis californica), which according to one forager may have a laxative effect.

Hors d’Oeuvres

Lightly Pickled Mussels with Sweet Chile Syrup

Hot and Cold–Smoked Steelhead Trout with Camas Bulb Cake and

Yerba Buena Crème Fraîche

Smoked Pork Jowl with Tomato Confit on Biscuit Root Biscuits

Piquillo Peppers with Crayfish Salad on Nettle Crackers

Barbecued Eel–Foie Gras Mousse Pinwheels

with Labrador Tea Gelée

Dinner

Duck Fat–Braised Cipollini Onion Skewers with Assorted Fruit

and Elk Jerky Dipping Powders

Cedar Paper–Grilled Sturgeon with Wild Greens

Local Quail with Acorn–Masa Tamales and Oregon

Grape Reduction

Seared Venison Sirloin with Wapato Root Mash and Wild Mint Choron Sauce

Dessert

Oregon Huckleberry Bombe with Toasted Honey–Douglas Fir Ice Cream,

Huckleberry Sorbet, Honeycomb and Douglas Fir Sablés

menu

PHOT

O bY

bON

NIE

HENd

ERSO

N

Preparing quail tamales.

JF12_FINAL.indd 20 12/22/11 11:45 AM

2 0 january/february 2012 | Northwest Palate | est. 1987 est. 1987 | Northwest Palate | january/february 2012 2 1 w w w. N o rt h w e st Palate . com

mor

rison presents

An experientiAl culinAry event series feAturing the best

food, wine, beer And spirits the region hAs to offer

ti ckets n ow avai lab le at m o r r iso n ki ds.o rg

“One of the most successful examples of a food and wine fundraising collaboration in the Northwest, if not the nation.”

Northwest Palate magazine

PHOT

O bY

bON

NIE

HENd

ERSO

N

•1poundhuckleberriescleaned(orsubtituteblue-berries,thawediffrozen)

•1cupsugar•2tablespoonscornsyrup•1pintwater

Many Native families in the Northwest still trek to the Cascades in late summer and make a weekend of picking huckleberries together, typically in the same field year after year. Not many still drink Douglas fir-needle tea, as their ancestors did; here the needles add a faintly rosemary-like fla-vor to the ice cream inside the bombe, or “mound.” Cooking the honey mellows its flavor. With this dessert Bennett also served a bite of honeycomb and sugar cookies to whose dough he added a sprinkling of finely minced Douglas fir needles before baking.

toasted Honey-douglas Fir ice Cream and Huckleberry sorbet bombe

Put huckleberries in a strong blender. Bring sugar, corn syrup and water to a boil to dissolve sugar. Pour the hot syrup into the blender. Puree, strain and chill overnight before churning in ice cream freezer according to the manufacturer’s directions.

Huckleberry sorbet

douglas Fir ice Cream

•1Douglasfirbranchletabout6incheslong

•3/4cuphoney•1quarthalf-and-half•14eggyolks•1/2cupsugar

Place branchlet and honey in small saucepan and bring honey to a boil. Add the cream and bring it back to a boil. Remove from heat and let it rest 10 minutes (no longer, or the fir flavor will be too strong). Return the mixture to a boil. Separately, whisk egg yolks and sugar together. Slowly add the hot honey and cream mixture, whisking con-tinuously. Return the mixture to a saucepan and heat, stirring, until mixture reaches 160˚ F on an instant read thermometer. Strain and chill over-night before churning in an ice cream freezer according to the manufacturer’s directions.

To serve: freeze a glass or metal bowl (or individual molds) for at least one hour. Line the inside with a layer of frozen huckleberry sorbet, return to freezer and freeze until solid. Remove from freezer; if any sorbet has slumped to the bottom of the mold, scoop it out and press it back into place. Pack the Douglas fir-honey ice cream into the middle of the mold, smooth the top and refreeze for at least several hours.

JF12_FINAL.indd 21 12/22/11 11:45 AM

2 2 january/february 2012 | Northwest Palate | est. 1987 w w w. N o rt h w e st Palate . com

two months earlier, as a semifinalist for 2011 Best Chef: Northwest by the James Beard Foundation probably didn’t hurt either.

It’s 7:45 p.m. at the James Beard House. Hors d’oeuvres have been passed, and Bennett and staff are setting out the first course, what Bennett describes as “deconstructed pem-mican.” Pemmican, to the uninitiated, is the original energy bar: an amalgam of dried meat and berries held together with lard, high in calories and easy to carry. In his redefini-tion, Bennett has braised cipollini onions in duck fat and served them, quartered and skewered, on a slab of wood accompa-nied by dipping powders of pulver-ized homemade elk jerky and freeze-dried fruit. Bennett showcased the ancient source of sustenance in a presentation at once true to its roots and contemporary.

“I wanted to take this food that’s been cooked for 10,000 years,” Bennett explains, “but do a modern menu with modern plat-ing, to show the timelessness of these foods and these people. They’re still eating these things—not necessarily every day. They’ve been here a long time. And they’re not going anywhere.”

Chef Bennett, wife Janel, and crew at the James Beard House.

CONTINUEd fROM PAGE 21

JF12_FINAL.indd 22 12/22/11 11:45 AM