Check-up With Dr. Strangelove - Filmmaker Magazine - Fall 2004

-

Upload

simone-odino -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of Check-up With Dr. Strangelove - Filmmaker Magazine - Fall 2004

7/23/2019 Check-up With Dr. Strangelove - Filmmaker Magazine - Fall 2004

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/check-up-with-dr-strangelove-filmmaker-magazine-fall-2004 1/7

mmaker

mer 2015: Click here to read the 25 New Faces of Film, plus interviews with The End of the Tour 's James Ponsoldt, The Look of Silence's Joshuanheimer and more...

lmmakingAllDirectingScreenwritingCinematographyProductionPost-ProductionFinancingDistribution

Transmediaolumns

AllThe Persona ProjectThe Week In CamerasLady VengeanceShooting With JohnThis is Where You WorkThe Blue Velvet ProjectThe Microbudget ConversationInto the SpliceH2N Pick of the WeekEditor's BlogCulture Hacker

estivals & EventsSundance

SXSWAll Festivals & Eventsnterviews

AllDirectorsActorsScreenwritersCinematographersEditors25 New Faces

WatchVideosVideo on Demand

atest Issue

witteracebookSS

ifp.orgFilmmaker Magazine

Gotham Awards25 New Faces

Log inJoin IFP

Contact us by email

Search

7/23/2019 Check-up With Dr. Strangelove - Filmmaker Magazine - Fall 2004

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/check-up-with-dr-strangelove-filmmaker-magazine-fall-2004 2/7

atures, Issues

y Terry Southern. Introduction by Nile Southern. In 1963, astanley Kubrick began production on Dr. Strangelove: Or How I earned To Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Terry Southernompleted a profile of the director for Esquire, which promplyhelved it. Earlier this summer it was finally printed in Killed:

Great Journalism Too Hot To Print (Nation Books), edited byavid Wallis. The abridged version of Southern’s article that

ollows is reprinted on the occasion of Sony Pictures Repertory’s0th anniversary presentation of Dr. Strangelove this fall.

HOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF FILM FORUM.

his is really the story of two killings.

the summer of ’62, my father received a fateful assignment from Esquire to interview Stanley

ubrick whose film Lolita was about to be released. Terry admired Paths of Glory, The Killing, and

partacus and, despite the list of canned (mostly trivial) questions from Esquire, engaged Kubrick a provocative discussion about film, literature, and eroticism. After submitting the piece through

s agent, it was clear Esquire wanted something more “gossipy” on Kubrick. Hoping to throw the

ditors off their celebrity blood hunt, Terry wrote:

…trying to establish [Kubrick] as a ‘wise-guy,’ ‘difficult,’ or having the reputation as such,

was so far off-mark that to have pursued it would have been altogether misleading.... He

does not know what [actress Sue Lyon] is going ‘to do next’. He suggested, as I was well

afraid he might, that I ask Hedda Hopper. Similarly, he had no opinion on Elizabeth

Taylor’s behavior in Rome…

s the interview languished at Esquire, Terry began working on the screenplay for Dr. Strangelove,

d in 1963 asked Esquire if he could do a piece on the movie. Incorporating bits of the squelched

terview, he found the time to write the article during filming. In the piece that follows, Terry

troduces the reader (and the masses) to Kubrick, this revolutionary film, and the all-important

nd ever looming) topic of the day: nuclear annihilation.

uch to his astonishment, the editors dismissed the article as a “puff piece” and prodded him to

o more gonzo. Esquire’s assistant managing editor suggested Terry “jettison most of the article”

d instead describe life in London “with his friends, books, parties and especially his own self.”

rry protested, quite presciently, that this was one of those “rare instances where something

enuinely great was at hand.” He wrote back:

I have obviously failed to persuade you as to the phenomenal nature of the film itself —

CHECK-UP WITH DR.

STRANGELOVE

VOD CALENDAR

Filmmaker 's curated calendar of the latest video

on demand titles.

See the VOD Calendar !

7/23/2019 Check-up With Dr. Strangelove - Filmmaker Magazine - Fall 2004

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/check-up-with-dr-strangelove-filmmaker-magazine-fall-2004 3/7

i.e. that it is categorically different from any film yet made, and that it will probably have a

stronger impact in America than any single film, play, or book in our memory. To say that

the piece is a “puff” is, to my mind, like saying that a piece about thalidomide babies is

“downbeat.”

ubrick’s insights into America’s military are eerily prophetic of the Bush administration,

rticularly the ideologues Wolfowitz, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Pearle, and their Project for a New

merican Century.

he idea of launching a “first strike,” had been anathema to all government and military policy

rategists since World War II. Amazing how now, preemption and even preemption with “low-

eld” nuclear devices is part of the dry rhetoric of the United States. It is, as Terry warns, “a

rious self-deception which tends towards making the unthinkable thinkable.”

— Nile Southern

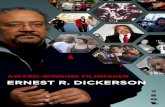

tanley Kubrick on the set of Dr. Strangelove.

Kubrick’s office, I counted sixty-three volumes concerned with nuclear warfare; they ran the

mut of possible approaches — from Unilateral Disarmament to The Preemptive Strike. But one

s only to listen to know his concern with the subject.

During the past six years,” he said, “I’ve read almost every available book on the nuclear

uation, including regular issues of Air Force Magazine, Missiles and Rockets, Bulletin of the

omic Scientists and so on. What has struck me is their cautious sterility of ideas, the reverence

obsolete national goals, the breeziness of crackpot realism, the paradox of nuclear

reatsmanship, the desperately utopian wish fantasies about Soviet intentions, and the terrifying

gic of paranoiac fears and suspicions. The present world seems very much like a neuroticralyzed by incompatible goals.”

was in October, 1961, at London’s Institute for Strategic Studies, that Kubrick’s hazy and

credible dream of “doing something about it” began to take on the bitter-sweet edge of reality.

astair Buchan, director of the Institute, told him about a certain novel he had just read which he

nsidered remarkable in its verisimilitude of how a nuclear war might start. The novel, published

1958, was written by a former RAF officer, Peter George, and was entitled Red Alert . Kubrick

ad it and was intrigued by its suspense, and by its technical authenticity — which had also been

rongly endorsed by Professor Thomas Schelling of Harvard’s Center For International Affairs; he

mediately bought the film rights.

e novel itself, though highly suspenseful, offered little more than a straightforward

elodramatic attitude towards the subject — not unlike that presented by its 1962 successor, Fail-

afe. (The basic similarities, incidentally, between Red Alert and Fail-Safe are embarrassingly

arp — so much so that the authors and publisher of the latter are now embroiled in a plagiarismtion brought against them by the English author Peter George.) In any case, the sort of

andard or prosaic approach afforded by melodrama, to the most astounding phenomenon in the

story of man, was not what Kubrick had in mind. “The present nuclear situation,” he has said, “is

totally new and unique that it is beyond the realm of current semantics; in its actual

plications, and its infinite horror, it cannot be clearly or satisfactorily expressed by any ordinary

heme of aesthetics. What we do know is that its one salient and undeniable characteristic is that

the absurd .” And so what Stanley Kubrick has done is to create the blackest nightmare comedy

t filmed. Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

e “War Room” at Shepperton Studios outside London is one of the largest indoor sets ever built.

is 130 feet long and 100 feet wide, with a 35-foot high ceiling. The walls are made of huge

ectronic world-target maps which cast back in weird reflection from the high-gloss black floor.

e mammoth circular table, seating the Prez and his council, is covered with green baize, like aonstrous gaming-table, and is 380 square feet in surface area. An equally important sequence of

e film takes place in a B-52 bomber — representative of those on their way towards Russian

rgets. “I’ve seen a lot of airplane pictures,” Kubrick said, “but I’ve never seen one where I got

e feeling of really being inside a plane.” To this end he spent $150,000 authenticating the

terior of a B-52, and in sending a 12-man camera crew to the far north in a specially equipped

17 photographic plane, where they shot 40,000 feet of moon-like Arctic ice-pack and wasteland

otage and it has resulted in some of the most convincing flying sequences ever filmed.

Buy/Access

Digital

Subscription

Read A Digital

Sample

Subscription

Help

Buy/Renew

Subscription

7/23/2019 Check-up With Dr. Strangelove - Filmmaker Magazine - Fall 2004

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/check-up-with-dr-strangelove-filmmaker-magazine-fall-2004 4/7

is accentuation of realistic detail is part of the overall concept which he has tried to impose on

e film — including character interpretation. A note at the front of the shooting script reads: “The

ory will be played for realistic comedy — which means the essentially truthful moods and

titudes will be portrayed accurately, with an occasional bizarre or super-realistic crescendo. The

ting will never be so-called ‘comedy’ acting.” This clearly derives from Stanislavsky’s own theory

r obtaining the highest comic effect from a given scene — namely, that if the situation is

herently funny, it should be played as though it were not — played, in fact, as gravely straight-

ced as possible. It is the difference between seeing a custard pie hit the face of a clown or the

ce of Herbert Hoover — one is predictably funny, the other outrageously funny. “I think that

rprise,” Kubrick said, “whether it occurs in love, war, business, or what have you, produces the

eatest effect of any single element. It gives the added momentum to the sort of see-saw of

motion from one position to another, and you get this extra push of thrill and discovery. I’ve

ways believed that in presenting realistic drama — as opposed to verse or impressionism — the

ly thing that justifies the time and effort of making it realistic is the power, the tremendousower, including the comic, which you can generate emotionally if you astonish the audience and

ow them to discover for themselves what your meaning is. People don’t like to be told anything

I mean I don’t think they even like to be told their pants are open. They love to discover things

emselves, and I believe the only way to do it is to lead them up to a certain place, and then let

em go the last distance alone — taking the chance, of course, that they may miss your point.”

ere is little danger that the points of Dr. Strangelove will be missed — although for Mr. and Mrs.

ont Porch Swing the suspense alone should suffice. For despite General Ripper’s ultimate suicide,

e recall-code is uncovered, and all but one of the planes are brought back; with this one,

owever, it is touch-and-go all the way. Its entire communications-system shot out, the “Leper

olony” — with veteran Texas pilot Major “King” Kong (Slim Pickens) at the stick — doggedly

esses on. (“Well, boys” he drawls in the classic John Wayne manner, “I reckon this is it — nuklar

m-bat! Toe to toe with the Rooskies! San An-tone!”) Meanwhile, back at the War Room,

esident Muffley speaks on the “Hot Line” (another case of fiction preceding fact) with theussian Premier, in an all-out cooperation to help him intercept the plane and stave off mutual

saster.

ubrick’s status among American film directors is most exceptional. At 34 he has directed seven

atures and two documentaries — including such divergent fare as the prize-winning Paths of

ory and the ten-million-dollar Spartacus. His real affinity however is with the European school

ho think of themselves not as directors but as filmmakers. The distinction is the area of

sponsibility assumed toward the film as a whole. Aside from directing, the filmmaker prepares

s own script, supervises set design, imposes the lighting values, and finally spends eight hours a

y in the cutting room editing the footage. Kubrick’s interest ranges beyond that, into designing

s own ads and translating foreign titles. When the French, Italian, Spanish, and German titles for

r. Strangelove were designated by the studio and reached his office, he revised each of them in

nsultation with Oxford language professors, who, of course, readily agreed they were faulty.ot since Chaplin or Welles has anyone achieved the kind of autonomy which Kubrick has vis-à-vis

hatever major studio happens to be financing his film, and it is certainly unique for one his age.

t’s the first time I’ve worked on an A picture,” said George C. Scott, “where there wasn’t

mebody from the front office snooping around. I guess they’re afraid of what they might see — I

ean maybe they don’t understand Kubrick or what he’s trying to do, but they do know how good

is.”

ubrick himself is of a somewhat different opinion: “When the

ajor studios started unloading their back catalogue of films

to the television networks, movie attendance — which was

ready in a steady decline — took a nosedive that was really

arming. Now these studios are beginning to realize that to get

ople back into cinemas they have got to produce films of a

fferent order from those being shown on TV. A new group of rsighted men, like Mike Frankovitch of Columbia, are leading

e way in this — and it is extremely encouraging, not only for

e creative people in the industry, but for movie-goers, and for

e culture generally.”

ubrick has a frightening amount of controlled energy; he

eeps little, and while his assistants are reduced to an almost

raight diet of dexies in order to keep abreast, he coolly

unches a sedative and plays blitz-chess, at a point (sterling) a

ece, during the lunch break. He also possesses a curious

stern-like facility for dropping into states of complete repose,

emingly at will. During one of these I ask him what was the

st way to become a movie director — and his answer should

an inspiration to every young cineaste.

he important thing,” he said, suppressing a yawn, “is to start

the top.”

ddly enough, this is in keeping with his own self-made career, which he began at 21, by doing a

xteen-minute documentary called Day of the Fight — a day in the life of a boxer, from the time

wakes up in the morning until he steps in the ring that night.

ow much does it cost to make such a film?”

7/23/2019 Check-up With Dr. Strangelove - Filmmaker Magazine - Fall 2004

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/check-up-with-dr-strangelove-filmmaker-magazine-fall-2004 5/7

Well,” he said, “I knew this fighter, Walter Cartier, a very good middleweight boxer, and so I put

p the money and shot it, and we were supposed to share the profits. As for actual costs, the

mera — a 35-millimeter Eyemo — was ten dollars a day, and the cost of the film, developed and

inted, is about ten cents a foot. The only expensive thing on this film was doing an original

usic score. The whole film cost 3,800 dollars, and 2,800 of it was for the sound.”

nd what did you do with this film?”

Well, I didn’t know what to do with it — but I called up RKO, because they were using a lot of

orts at the time, and asked them to have a look at it. They did, and they bought it — for 4,000

ollars, so I had picked up a quick 200 on it. I mean it only took about four months to put it all

gether... but the important thing was they advanced me 1,500 to make another one.”

nd then what happened?”

Well, these small things led from one to another until I met James Harris, a very courageous and

rceptive young man, and he was able to raise some money so we formed our own company. Up

til then I hadn’t been able to consider the content of a story or anything like that — I had to use

hatever material came to hand, simply to keep functioning in the medium. But now we were able

start thinking in terms of buying good stories and taking the time to develop them. We bought

novel called Clean Break , by Lionel White, and made it into The Killing. That’s the first film I

ade with decent actors, a professional crew, and under the proper circumstances.”

nd then you made Paths of Glory ?”

es. That was a book I had read when I was about fourteen, and one day I suddenly remembered

”

Wasn’t there some controversy over the ending of that film — where the French soldiers are

ecuted for desertion?”

Well, it wasn’t a controversy — I mean there are always a lot of people around a film studio who

e to give artistic advice, and they said ‘You’ve got to save the men at the end!’ but, of course, itas out of the question. It would have been like making a film about capital punishment in which

e innocent man is saved — it would have been pointless.”

ow what about your involvement with Marlon Brando on One-Eyed Jacks?”

es, that was a curious involvement. We became friendly, and he told me about this ‘western’ he

anted to do — and I was to direct it. So we spent six months working on the script — Marlon,

alder Willingham and myself, along with Guy Trosper, George Glass, Carlo Fiori, Walter Setzer,

ank Rosenberg... and maybe some others. But it ’s really a much too complex and Kafkaesque

ory to go into now.”

have here a quote from Brando about you — ‘Stanley is unusually perceptive and delicately

tuned to people. He has an adroit intellect and is a creative thinker, not a repeater, not a fact-

therer. He digests what he learns and brings to a new project an original point of view and a

served passion.’ What do you say to that?”

Well, Marlon is very generous, of course — but surely it’s possible for two ‘adroit, perceptive and

licately attuned people’ not to agree in any way, shape or form.”

understand that the only picture you’ve done where you weren’t your own boss was Spartacus

how did that occur?”

When the thing with Marlon didn’t work out, I had nothing to do, and they asked me to direct

partacus. So I did that. Yes, it’s the only picture where I was employed — and I found that’s the

rong end of the lever to be on. In a situation like that the director has no real rights, only the

ghts of persuasion. And very often you fail to persuade — and even if you do, you’ve wasted so

uch time you may find you’ve overlooked some even better ideas than those you had to push

r.”

erry Southern, photographed by Stanley Kubrick near Shepperton

tudio, England, 1963. PHOTOGRAPH FROM THE TERRY SOUTHERN

STATE PRIVATE COLLECTION, COURTESY OF NILE SOUTHERN.

ubrick and Harris first read Lolita in the original Olympia Press edition, and they bought the film

ghts to it for $150,000 before it became an American bestseller. Shortly afterwards they declined

offer of $500,000 for the book. Kubrick himself now admits to a keen interest in affairs of high

7/23/2019 Check-up With Dr. Strangelove - Filmmaker Magazine - Fall 2004

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/check-up-with-dr-strangelove-filmmaker-magazine-fall-2004 6/7

ance, and he is by all accounts an astonishingly adroit businessman.

love to gamble,” he said, “and games of logic and intuition have always fascinated me.

e financial aspect of filmmaking is like a three-dimensional poker game, composed of logic,

ychology and instinct. It’s a game the filmmaker has to play, and to win — or he simply will not

in a strong enough position to make the kind of films he wants.”

Did Lolita present any problems which were different from those of your other films?”

es, I think the process of trying to gradually penetrate the surface of comedy which overlies the

ory, and reach the ultimate tragic romance of it, put it in a category apart from the others. In

rms of format, all of my other films, including Dr. Strangelove, have been strongly plotted,

hereas Lolita was more purely a mood piece — like music, a series of attitudes and emotions that

rt of sweep you through the story.”

Do you feel that the totality of your work has any specific goal or direction?”

erhaps, in a very personal sense. In making a film I generally start with an emotion. The theme

d the technique come as a result of the material passing as it were, through myself and coming

t of the projector lens. It seems to me that a genuinely personal approach, whatever it may be,

the goal. Chaplin, Bergman and Fellini, for example, although as different in their outlooks as

ossible, have achieved this, and I’m sure it’s what gives their films an emotional involvement

cking in most work.”

uring my visits to the Strangelove set I heard a number of interesting anecdotes about Kubrick’s

fts as a director — that is to say, as a manipulator of the human personality in creating a film.

ne of the most striking of these was told by his English associate producer, Victor Lyndon, who

orked with him in Germany on Paths of Glory . This is a film about the French Army in World War

several hundred German police were used in the movie to portray the French infantry regiment

which the story is focused.

hey were the most disciplined extras in the world,” Lyndon said. “They would do exactly as theyere told, and between takes they would sit for hours without saying a word — rather frightening

tually. Well, in this particular scene they were supposed to advance across about a hundred

rds of broken terrain under heavy shell fire. The first time they did it so fast, so efficiently fast,

at it was hardly more than a blur in the lens. Kubrick told the interpreter to tell them to do it

e-quarter as fast. The second time, it was still much too fast and likewise with the third, fourth

d so on, despite these renewed instructions each time. There seemed to be no way to get these

aps to slow down. Well, Kubrick sat there staring at them for a while, and then he went over to

e interpreter and said, ‘Listen, tell them to remember that they’re not German soldiers now,

ey’re French soldiers.’ The interpreter said this, and a great bloody roar of laughter went up —

e only sound they had made all day — and when they crossed that field again, by God it was

rfect.”

om beginning to end, Dr. Strangelove is, among other things, an unrelenting indictment of the

ecious logic and the conveniently flexible semantics which have served militarists and politicianssuch good stead from time immemorial.

ophisticated nuclear strategists also speak a language all their own. They are gradually evolving

terminology which is free of moral, or even human, connotation. They do not, for example, use

y form of the word attack, but use instead the term preempt — which, of course, sounds like

mething in a bridge game rather than what it is. One of the most outlandish of their new words

megadeath — thus allowing the estimates of loss of human life (in case Russia should preempt)

be expressed in an easily digestible form: “New York Area, 12.7 megadeaths” (whereas should

e preempt and so only have to absorb the limited counterstrike, the same area is rated at “4.3

egadeaths.”) Preempt is supposed to mean “delivering the initial strike in the knowledge that an

emy strike is in preparation” — naturally the words “in preparation” are variously interpreted.

ehind the use of such euphemisms as “preemptive strike” and “4.3 megadeaths” — instead of

elling it out as “attack” and “four million, three hundred thousand dead” — is a curious self-

ception which tends towards making the unthinkable thinkable.

obably the most sophisticated concept now on the boards is that of the “ultimate deterrent” —

e so-called Doomsday Machine. This world-suicide apparatus is formed by a complex of gigantic

clear devices (as the bombs are called) encased in a cobalt compound and buried in the earth.

e theoretical value of the Doomsday Machine is that it dramatically negates the usefulness of a

clear attack on the nation possessing it, because the cobalt-casing means that the bomb, if

ploded, will produce a lethal cloud which within six months will enshroud the surface of the

rth, destroying all life, plant and animal, for a duration of ninety to one hundred years. The final

phistication of the machine is that it is so designed that it cannot be untriggered, even by the

tion possessing it — thus its effectiveness is not to be impaired by threats or bluffs. Should a

tion convert its defense strategy to the use of a Doomsday Machine, it would need no other

clear armaments. Some strategists foresee this eventual likelihood for both Russia and China,

hose economies could be more advantageously geared to projects other than armament

oduction.

hen President Muffley gets the Soviet Premier on the phone and “explains” that a wing of

clear bombers is mistakenly on its way to Russian targets, and asks for his assurance that this

ll not be regarded as a hostile act, he is dismayed to learn that Russia does, in fact, now have a

oomsday Machine — it was to be announced at the People’s Congress the next day — which

nds a bit of spice to the already mounting suspense, for it is set to trigger if an explosion of the

enty-megaton range occurs anywhere in the Soviet Union. Finally, when all efforts to recall the

e remaining plane have failed, it appears that the end of the world is well at hand, and a pallor

7/23/2019 Check-up With Dr. Strangelove - Filmmaker Magazine - Fall 2004

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/check-up-with-dr-strangelove-filmmaker-magazine-fall-2004 7/7

e Magazine of Independent Film5 Filmmaker Magazine All Rights Reserved A Publication of IFP

ubscribessue Archivedvertiserivacy Policyupportontact Usite by AREA 17

despair engulfs the War Room.

Mister President,” says Presidential Aide Staines gravely, “how are we going to break it to the

ople — it’s going to do one hell of a thing to your image.”

eprinted by permission of the Terry Southern Literary Trust and Nile Southern.