CHAPTER-II POLITICAL BACKGROUND – THE MUGHALS AND...

Transcript of CHAPTER-II POLITICAL BACKGROUND – THE MUGHALS AND...

16

CHAPTER-II POLITICAL BACKGROUND –

THE MUGHALS AND THE SAFAVIDS

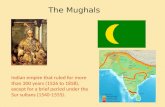

The Mughal Empire and the Safavid monarchy were among the four

leading Muslim powers of the 16th and 17th centuries. The Ottomans and

the Uzbeks of Central Dsia were other powers which constantly competed

with the Safavid for the control of the regions and the people on West,

North-Wet and North-East borders of Iran. At time the Uzbeks sought help

from the Mughals, on occasion the Ottomans and the Uzbeks coordinated

their moves against the Safavids. Diplomatic contacts subsisted at various

other levels between all these four great powers. The princes of the one

empire could cultivate relations with the sovereigns of the other. Dignitaries

of the one would correspond with those of the other. As regards the

Mughals, while the Safavids had close links with them, there were also

certain regions in the sub-continent of India with which Persian authorities

maintained direct diplomatic and trade contacts. There were two regions of

the sub-continent with which Iran maintained such links, in particular, the

Deccan, and the North-West frontier provinces, namely Kashmir, Kabul,

Lahore, Multan and Qandahar. The last of these, Qandahar, remained

alternatively in Iranian and Mughal hands and changed hands several

times during the two centuries. Then under the Mughals, its governor

would maintain contacts with Iran, and when under Persian occupation, its

governor would do likewise with Mughal authorities. 6

6 R. Islan , Iran and the Mughal Frontier Provinces" in: Culture of Iran, Vol. XXI, Nos.1-4, Tehran,

1979,

17

The Mughal Empire and Safavid Iran had enough in common regarding

faiths and cultural and territorial interest to encourage long periods of

peace, although the aain territorial issue between them was for the control

of Qandahar. During the 17th century, the Deccan kingdoms, with their

political and Shi'ite religious to Iran, also caused tension in Mughal -

Safavid relations.

The rise of the Safavids in Iran and the Mughals in India were almost

synchronous. (XX) The military assistance of Isma'ill Safavid proved to be

of great moral value to Babur in Central Asia.7 The diplomatic relations

were first established by Ismail I who, after the conquest of Merv in 919

A.H./151- A.D., and the death of Shaibani (Shaibak) Khan treated Babur's

sister Khanzada Begum8, one of the captives with great respect and sent

her along with his ambassador to her brother. Babur received the embassy

of Qunduz, where he had come at the invitation of Khan Mirza, and he in

return sent an emissary to thank the Shah9.

In 933 A.H/1524 A.D., Shah Isma'il I died and was succeeded by his

eldest son Tahmasbl. Two years after his, Babur conquered Delhi and

Agra in 935 A.H./1526 A.D.,10 and became the emperor of India. He used

this occasion to display his instinct of

7 •J.N. Sirkar, "Correspondence between the Deccani Sultanates and Mir Jumla with the court of Iran", In: 3J.B,O.R.S., March, 1942, vVol.XXVH, p. 65. 8 A. Rahim, "Mughal relations with Persia", in: Islamic Culture, Vol.VII, 1934, p. 463. Quoted from Babur's Memoirs, pp. 15, 19 and Tarikh-i-Rashidi, pp. 175, 186. 5 9 Ibid., p. 463. 10 J.L Nehru, "The Discovery of India", Calcutta, 1946, p. 162; A.A.Jorfi, Iran and India", Age-old Friendship 'n: India Quarterly; Vol. I, No.4, 1994, p. 77.

18

generosity and bestowed rewards on all and sundry. He also sent

presents to some people in Khurasan and Iraq (Western Persia)11

I prefer to explain Babur's biography - founder of Mughal Emperor

Dynasty of India before writing relationship between Safavid rulers and

Mughal emperors from 1501-1722 A.D. Because I explained about Ismai'ii

and his genealogy in the first Chapter (Historical Background).

Babur:

Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad, commonly known as Babur Shah, son of

'Umar Shaykh Mirza, was the sixth descendant of Timur and the founder of

the Mughal Empire in India. He was born on the 6th of the month of

Muharram 888 A.'H./15th Feb. 1481 A.D. at Farghana. He was connectd

with both the families of Timur and Chingiz Khan. Thus, he had in him the

blood of the two greatest conquers of Central Asia. At the early age of

12the century (899 A.H./1492 A.D.), his father Sultan 'Umar Shaykh Mirza,

died and Babur became the ruler of Farghana. He sat on his hereditary

throne at Andijan, the capital of Farghana. At the time of his accession, he

was surrounded on all sides by his enemies. His uncles and cousins took

advantage of his youth and inexperience and attacked him right and left.

Ahmad Mirza attacked Babur in 901 A.H./1494 A.D. Farghana for Babur,

his attack failed and he himself died in 1499 A.D./906 A.H. It was now the

turn of Babur to have his revenge and he took full advantage of the

confusion. that, prevae in Samarqand after the death of Ahmad Mirza, his

11 'Allami. Abul Fazl, Akbar Nama, Vol.I, Bib. Indica, Calcutta, 1877-78, p. 99; Bakhshi. Khwaja

Nizam-ud-Din Ahmad, Tabaqat-i-Akbari, Bib-lndica, Vol. II, Calcutta, 1931, p. 17; Badauni. 'Abd-ul-Qadir,

Muntakhab-Tawarikh, Bib-lndica, Vol. I, Calcutta, 1868, p. 337.

19

uncle. In November, 1501 AD/908 A.M., Babur was able to capture

Samarqand. Unfortunately, while at Samarqand, Babur fell ill and his

Ministers gave out that he was dead. They also put on the throne the

younger brother of Babur named Jahangir.

As soon as Babur recovered from his sickness and came to know of

the trick played upon him. He marched from Samarqand to recover

Farghana. Due to his ill-luck, Babur lost both Samarqand and Farghana.

He could not capture Farghana because Jahangir was securely

established there and as regards Samarqand, it was occupied in his

absence by his cousin, 'Ali. The result was that in 1502 A.D./909 A.H.,

Babur was not the ruler of any place. His only possession was Khojand.

He had to live a wanderer's life more than a year. However, in 1504

A.D./910 A.H., he was able to recapture the capital of Farghana.

In 1504 A.D./911 A.H., Babur conquered Samarqand for the second

time but he was forced by the Uzbeks to leave the same. After the loss of

Samarqand, he lost Farghana also in the same year. The result was that

after all these ups and downs of life, Babur was left with nothing in 1506

A.D./913 A.H. when he led his major offensive against India. In the interval,

Babur conquered Qandahar and Heart. In 1515 ?A.D./922 A.H. he again

tried his luck to conquer Samarqand after the death of Shaybani Khan. He

entered into an alliance with the Shah Isma'ill, and captured both Bukhara

and Samarqand. However, he was not destined to sit on the throne of

oamarqand for long. Within less than a year he was driven out of

Samarqand.

It was only after his final failure in Samarqand that Babur paid his full

attention to the conquest of India. He himself wrote thus in 1526 A.D./933

20

A.H.: "From the time I conquered the land of Kabul till now, I had always

been bent on subduing Hindustan. Sometimes, however, from the

misconduct of my Amirs (commenders), sometimes from the opposition of

my brothers, etc. I was prevented. At length, these obstacles were

removed and I gathered an army (1519 A.D./926 A.H.) and marched on to

Bajour and Swat and thence to advance to Bhera on the West of the

Jhelum River.12

Babur reached as far as the Chenab in 1519 A.D. Acting on the

advice of his ministers, he sent an ambassador to Ibrahim Lodi demanding

the restoration of the country which belonged to the Turks. The

ambassador was detained at Lahore and came back empty handed after

many months. After conquering Bhera Khushab and the country of

Chenab, Babur went back to Kabul.

In 1520 A.D./927 A.H., Badakhshan was captured and put under the

charge of Humayun. In 1522 A.D./929 A.H. Qandahar was captured and

given to Kamran.

At this time, Babur received many invitation and those camp

particularly from Daulat Khan Lodi, Governor of Punjab; 'Ala-ud-Din, uncle

of Ibrahim, and Rana Sanga. There could be on better chance for him to

fulfill his ambition of conquering India. Babur at once started and reached

Lahore. On his arrival at Lahore he found that Daulat Khan Lodi had

already been turned out by an Afghan chief. Babur defeated the Afghan

chief, captured Lahore and left for Kabul after appointing 'Ala-ud-Din as the

governor of Lahore. All this happened in 1524 A.D./931 A.H. However, 12 Mahajan, V.D., "India Since 1526", 1985, pp. 7-8.

21

'Ala-ud-Din was not allow60' to stay long at Lahore and he was driven out

by Daulat Khan Lodi. 'Ala-ud-Din ran away to Kabul.

Battle of Panipat (1526 A.D./933 A.M.}"

After making elaborate preparations, Babur set out for the conquest

of India. First of all, he had to deal with Daulat Khan who had turned out

'Ala-ud-Din from Lahore. After defeating hifti, Babur advanced to Delhi via

Sirhind. Ibrahim Lodi came out of Delhi to give battle to Babur. The

opposing armies met on the historic plains of Panipat. Babur had certain

advantages. His artillery worked wonders. In spite of the superior

numerical strength of Ibrahim Lodi's armies, he was defeated and killed in

the battlefield. The result was that the kingdom of Delhi and Agra fell into

the hands of Babur.

According to Dr.lshwari Prasad: "The battle of Panipat placed the

empire of Delhi in Babur's hands. The power of the Lodi dynasty was

shattered to pieces and the sovereignty of Hindustan passed to the

Chaghtay Turks".

"Just as Clive's victory at Plessey has a great significance in the

establishment of the British rule in India, similarly Babur's victory in the first

battle of Panipat has a great significance in the establishment of Mughal

kingdom in India. These battles were pillowed by some greater brilliant

victories like those of Kanwah in the case of Babur And Buxar in the case

of Ciive. Just as the Mughal Empire was established after Kanwah,

similarly British rule was established after the battle of Buxar13

13 Mahajan, V.D., Ibid., p. 8.

22

Dr.R.D. Tripathi observes: "The battle of Panipat brought Babur to

the end of the second stage of his India conquest. It sealed the fate of the

Lodi dynasty as effectively as his ancestors; Timur had done of the

Tughlaqs, and told seriously on the morale and already weak organization

of the Afghans. The soldiers and the peasantry alike run away in fear of

the conqueror; gates were shut of every fortified town, and Afghans was

broken, and the leaders of its various tribes were rent asunder and

demoralized... Finally, the victory of Panipat laid the foundation of the great

Mughal Empire which in grandeur, power and culture was the greatest in

the Muslim world and could even claim equality with the Roman Empire. 14

After the battle of Panipat, Babur sent his forces at once to occupy

Delhi and Agra. On 27th April 1526 A.D./933 A.H., the Khutba15was read in

the principal mosque of Delhi in the name of Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad

Babur, the first of the great Mughal.

Mughals. Actually they were Birlas Turks. In his early days, Timur

had to fight bitterly against the Mughals before he could overcome them.

They eventually succeeded in expelling Babur from the home of his

fathers. However, the term 'Mughal' had become a generic term for warlike

adventures from Iran to central Asia. Although Timur and his descendants

hated the name 'Mughal', it was their fate to be known as the Mughals. It

seems too late of correct the error now. The Arabic from the name is

14 Rise and Fall of the Mughal Empire, p. 35. 15 Khutba is a form of praise and prayer consisting of four parts: (1) The praise of God, (2) of Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon him) and his twelve descendants (it is permit in Shi'a, Sect), (3) of royalty, (4) and prayer for the reigning sovereign. The mention of the Emperor's name in the Khutbah constitutesa legal proclamation of his accession to the throne. See Kitto's "Curt of Persia", p. 160-1

23

Mughul or Muahool but in India, it has assumed the form Mughal. The

Portuguese used the form 'Mogor".

Babur had to meet with certain difficulties. The Rajputs were not

friendly to him. There were many Afghan chiefs who considered their

claims to be superior to that of Babur. Moreover, his own followers began

to desert him an account of the hot climate of the country. It was the iron

will of Babur that saved the situation. He made it clear to his followers that

he was determined to stay on in India and those who wanted to go back to

Kabul might do so happily. The result was that with the excepton of a few

persons, the rest of his followers decided to sink or swim with their own

leader.

Battle of Kanwah, 1527 A.D./934 A.H.

The victory of Panipat did not make Babur the Emperor of India. He

met a stronger foe in Rana Sanga of Mewar. The letter had the ambition to

occupy the throne of Delhi itself. Such a formidable foe had to be disposed

of if Babur was to have an unchangeable position.

In 1527 A.D./934 A.H., Rana Sanga adanced with a large army to

Biana. Babur also advanced to Fatehpur Sikh. The advanced-guard of

Babur was defeated by the Rajputs and the result was that his folloers got

disheartened. At this time, Babur showed his qualities of leadership. He

ordered the breaking of the cups of wine. He repented of his past sins and

promised to give up wine for the rest of his life. He addressed his soldiers

in these words: "Noble men and soldiers! Every man that comes Into the

world is subject to dissolution. When we are passed away and gone, God

only survives unchangeable. Whoever comes to life must, before it is over,

drink the cup of h ath He who arrives at the inn of morality must one day

24

inevitably take his departure from the house of sorrow-the world. How

much better is it to die with honor than to live with infamy?

With fame, even if I die, I am contented;

Let fame be mine, since my body is deaths.

"The most High God has been propitious to us, and has now placed

us in such a crisis if we fall in the field, we die the death of martyrs; if we

survive, and we raise victorious, avengers of the cause of God. Let us,

then, with one accord swear on God's holy word, that none of us will even

think of turning his face from his warfare nor desert from the battle and

slaughter that ensues, till his soul is separated from his body"16

The appeal of Babur had the desired effect and he started the attack

with heavy I artillery fire. Then, according to Farishta, Babur himself,

charged like a lion rushing from his lair. After an obstinate battle, the

Rajputs were defeated and Babur became the Victor of Kanwah,

Regarding the importance of the battle of Kanwah, Prof.Rushbrook

Williams has observed thus: "In the first place the menace of Rajput

supremacy which had loomed 'arge before the eyes of Mohammedans in

India for the last few years, was removed once for all. The powerful

confederacy which depended so largely for its unity upon the strength and

reputation of Mewar, was shattered by a single great defeat and ceases

henceforth to be a dominate factor in the politics of Hindustan. Secondly,

the Mughal cmpjre of India was soon firmly established. Babur, had

definitely seated himself upon the throne of Sultan Ibrahim, and the sign 16 Mahajana V.D., "India Since 1526", 1985, pp. 9-10.

25

and seal of his achievement had been the annihilation of Sultan Ibrahim

most formidable antagonists. Hitherto the occupation of

Hindustan might have been looked upon as a mere episode in

Babur's career of adventure; but from henceforth it became the keynote of

his activities for the remainder of his life. His days of wandering in search

of fortune are now passed away. The fortune is his, and he has to show

himself worthy of it. And it is significant of the new stage in his career

which this battle marks that never afterwards does he have to stake his

throne and life upon the issue of a stricken field. Fighting there'is, and

fighting in plenty, to be done; but it is fighting for the extension of his

power, for the reduction of rebels, for the ordering of his kingdom. It is

never fighting for his throne. And from it is Iso significant of Babur's grasp

of vital issues that from henceforth the center of gravity of his power is

shifted from Kabul to Hindustan."17

Dr.R.D.Tripathi says: "The consequences of the battle were indeed

far-reaching. It broke the Rajput confederacy which depended for its

existence not an any enlightened conception of race, community, religion

or civilization, but on the prestige of the Udaipur House, the military and

diplomatic victories of its warlike leaders, who had now lost their moral

prestige. With the break-up of the confederacy vanished the nightmare of

Hindu supremacy which had kept the Muslim states in Northern India in

anxious suspense. The destruction of many of the most redoubtable

Rajput chiefs and the disintegration which set in after Rana Sanga became

helpless, once more laid open Raiputana to the ravages of the neighboring

powers, which were only too rady step in. Kanwah removed the most 17 Williams, Lf. Rushbrook, An Empire Builder of the Sixteenth Century, pp. 156-157.

26

formidable obstacle in the way of the foundation of the Mughal Empire.

Babur assumed the title of Ghazi (warrior of holly war) and his throne in

India was now quite secure. The centre of gravity of his power now

definitely shifted from Kabul to Hindustan. Finally, the defeat of the

Rajputs weakened the hands of the

Afghans. With the help of the powerful and Independent chiefs of

Rajputana, they would have been certainly for more formidable rivals of the

Mughals than single-handed."18

According to Dr.G.N. Sharma: "But, whatever may have been the

causes of the defeat, the consequences of the battle of Kanwah wee

immense and immeasurable. The battle had not proved to be a light

adventure for Babur who had almost staked his life and throne and

suffered a grievous loss in men and money before he could claim success.

Nevertheless, the victory had far-reaching results and shifted the

sovereignty of the country from the Rajputs to the Mughals who were to

enjoy it for over two hundred years. It would be however a mistake to

suppose that the Rajput power was crushed for ever and those why

wielded no influence in the politics of the country. No one realized it better

than Babur himself who stopped short of further encroachment upon

Rajasthan After Kanwah he did nothing more than storming Chanderi and

obtaining possession of that fortress on 29th January 1528 A.D./935 A.H."19

18 Rise and Fall of the Mughal Empire, p. 43. 19 Zmshsjsn, B.F., "India Since 1526", pp. 9-10.

27

After losing the battle of Kanwah, Rana Sanga took a vow never to

enter the portal of Chittur without defeating Babur. When he heared of

Babur's siege of Chanderi, he started for that place. However, he died in

January, 1528 A.D., before he could render any help. ^

According to Dr. Sharma, in spite of heroism, Rana Sanga was not a

statesman of high order. "In his relations with Babur he showed vacillation

and want of decision and firmness. He broke the agreement with Babur.

Even after he had decided not to help him, he failed to proceed and

capture Agra which he ought to have done immediately after Babur had

moved south of Punjab to fight with Ibrahim Lodi. Had he done so he

would have not only acquired the immense treasures and resources that

lay stored in that town but also the support of the entire race of the Indian

Afghans and other notables who were at that time thoroughly inimical to

Babur. He occupied himself after Babur's victory at Panipat in the more

congenial task of the establishing his rule over the territory in Rajasthan

that still belonged to the Afghans instead of making preparations for a

contest with Babur. After he had conquered Bayana he did not engage

Babur for about a month and foolishly allowed him time to complete his

preparations. He proceeded from Bayana to Kanwah by a long route that

took him a month, though from Bayana Khanwa could have been reached

in a day's time. He railed to appreciate the strength and weakness of

Babur's position and military establishment. The greatest mistake of his

life, however, must be considered to be his failure to make an alliance with

Ibrahim Lodi for driving away Babur who was then a foreigner and hence

an enemy not only of Ibrahim but also of all Indians of that time. An

impartial student of history must, therefore, conclude the chapter of

Sanga's relation

28

ith Babur by adding that the former was completely outwitted by the latter

in diplomacy and war"20.

Battle of Chanderi (1528 AD.1935 A.M.) As a result of the battle of Kanwah, the power of the Rajputs was

crippled, but not crushed. Babur marched against Chanderi which was a

stronghold of the Rajputs under Medini Raj. This Rajput chief was very

powerful and had made.his position felt in Malwa. Babur reached Chanderi

on 20th January 1528 A.D./935 A.M. The Mughals besieged the fort where

Medini Raj had taken shelter with 5000 followers. Medini Raj refused to

enter into any treaty with Babur and also did not accept Babur's offer of a

Jagir (State) in lieu of Chanderi. Consequently, Babur pressed the siege of

Chanderi with full vigor and attacked the fort of Chanderi from all sides.

The Rajputs were determined to fight to the finish and their women burnt

themselves by performing Jauhari (Acid). Almost all the Rajputs lost their

lives. On 29th January 1528 A.D./935 A.H. the Fort of Chanderi was

captured. After this on other Rajput chief could challenge the authority of

Babur.

Battle of Ghagra (1529 A.D./936 A.M.): Although the Rajput menace was removed, there were still the

Afghans who had , he subdued. Mahmud Lodi, a brother of Ibrahim Lodi,

had fled and taken refuge in Bihar and established his position there. He

had a large army estimated at about one lakh (100,000) strong. Supported

by this army, he went to Banaras and from there to Chunar. When he laid

siege to Chunar, Babur sent his own son 'Askari aginst Mahmud Lodi and 20 Rise and Fall of the Mughal Empire, p. 43.

29

later on himself marched against him. When the Afghans came to know of

the movement of Babur, they raised the siege of Chunar and withdrew and

a number of Afghans chiefs offered their submission to Babur. Mahmud

Lodi had taken refuge in Bengal. Although its ruler, Nusrat Shah had

assured Babur of his friendship, Babur decided to put and the Afghans

were completely defeated. Babur's artillery rendered him great service in

his action against the Afghans. The defeat of Ghagra was final so far as

the Lodis were concerned. Babur entered into a treaty with Nusrat Shah by

which both the parties agreed to respect each other's sovereignty and

Nusrat Shah agreed not to give shelter to the enemies of Babur in future.

It was in this way that "in three battles Babur had reduced northern

India to submission."21' The rest of his fife was spent in organizing the

administration of the provinces which formed his new kingdom. His system

was purely feudal. He divided his territory into a large number of Jagirs and

those were distributed among his officers. Those officers were responsible

not only for the collection of land revenue on those Jagirs but were also in

charge of the civil administration of those areas. Much of the territory

remained in the hands of the native land holders whether they were Hindus

or slims We are told that from the provinces "west to east from Bhera and

Lahore to Rahraich and Bihar and north to south from Sialkot to

Ranthambhar," Babur got an equivalent of £ 2,600,000 as land revenue.

Death of Babur:

The circumstances leading to the death of Babur in December, 1530

A.D./936 A.M., are curious. It is stated that his son, Humayun fell sick and

it was declared that there was no possibility of his survival. It was at this 21 Mahajan "India Since 1526", 1985, p. 12.

30

time that Babur is said to have wlkd three times round the bed of Humayun

and prayed to God to transfer the illness of his son to him. He uttered the

following words: "I have borne it away! ,l have borne it away!" It is stated

that from that time onward Humayun began to recover and condition of

Babur went from bad to worse and ultimately he breathed his last22. Before

dying he addressed the following words to Humayun: "I commit to God's

keeping you and your brothers and all my kinsfolk and your people and rny

people. And all of these I confide to you."23

At the time of his death, Babur was hardly 48 years of age. However,

he was the king of thirty-six years, crowded with hardship, turmult and

strenuous energy. In it appears from the account of Gulbadan that Babur

fell ill that very day and died soon after. But according to accordance with

his will, his dead body was taken to Kabul and there lies at peace in his

nrave in the garden on the hill, surrounded by those he loved, by the

sweet-smellling flowers of his choice and the cool running stream; and the

people still flock to the tomb and offer prayers at the simple mosque which

an august descendant built in memory of the founder of the Indian Empire.

Administrative Changes In spite of the fact that Babur spent most of his time in fighting he

was able to make certain changes in the administration. He replaced the

weak confederal monarchy of the Afghans by divine right despotism. The

position of the king was raised so high that even his highest nobles had to

22 Dr.lshwari Prasad, Babur was sickly for two or three months after the recovery of Humayun. The latter was

Summoned to the capital from his Jagir when the condition of Babur became serious. According to S-R- Sharma,

the death of Babur was due to the poison given to him by the mother of Ibrahim Lodi. Gulbadan also refers to 1e this fact 23 Mahajan, V.D., Ibid., p. 12.

31

behave as if they were merely his servants. The Prime Minister of Babur

served as a link between him and the departmental heads and this post

was held by Mir Nizam-ud-Din Khalifa. Babur introduced Persian ways and

manners in the court. He built a large number of palaces underground

rooms. Baolis (reservoir) and public baths. He gave a sense of urbanity

and stability to the Government. He gave high appointments to Afghans

and Hindus. Dilawar Khan Lodi was given the title of Khan-i-Khana. He

tried to play the Afghans against one another.

Babur set up Dak Chaukis (Courier Office) at intervals of 15 miles. At

each Dak Chauki, he maintained good horses. It was with their help that

Babur was able to get news from distant places. The local officers in the

provinces and districts enjoyed a lot of autonomy and it would have been

difficult to exercise any effective and comprehensive control over them.

Babur was not able to take any steps for the promotion of agriculture. His

fiscal policy was also defective. He squandered away the easures of Delhi

and Agra and hence had to face a lot of financial difficulty.

Babur was not prepared to accept the authority of the Caliph over

himself. He asserted the supremacy of the ruler. He also followed a policy

of religious toleration. He married the daughters of Medini Rao to

Humayun and Kamran. He accepted the son of Rana Sanga as a Vassal.

He got from him Ranthambore but gave him Shamsabad in exchange.

'Abbas Khan-i-Sarawani put the following words into the mouth of

Sher Khan about the administration of Babur: "Since I have been amongst

the Mughals, and know their conduct in action, I see that they have no

order or discipline that their kings, from pride of birth and station, do not

personally superintend the government, but leave all the affairs and

32

business of the State to their nobles and ministers, in whose saying and

doings they put perfect confidence. These grandees act on corrupt motives

in every case, whether it be that a soldier's or a cultivator's or a rebellious

zamindar's (landlord). Whoever has money, whether loyal or disloyal, can

get his business settled as he likes by paying for it, but if a man has no

money, although he may have displayed his loyalty on a hundred

occasions, or be he a veteran soldier, he will never gain his end. From this

lust of gold they make no distinction between friend and foe."24

Estimate of Babur:

Babur was one of the most interesting figures in the history of

Medieval lndia= He not only a warrior but a great scholar and poet. All his

life he was struggling for and ultimately got the same. In his case, adversity

was a blessing in disguise. He possessed of such an indomitable will that

no amount of difficulties could shake his faith in himself. He was a lover of

nature. He loved poetry and drinking. He was frank and jovial. He

retained these qualities up to the very end of his life. He was an *

orthodox Sunni but not a fanatic like Mahmud of Ghaznavi. He wrote

about Hindus with contempt and recognized Jihad (holy war) against them

as a sacred duty.

According to Sir E.Denison Ross, Babur was one of those men who

are so active in mind and body that they are never idle and always find

time for everything. As a soldier, Babur was fearless in battles. As a

general, he was a great tactician with a keen eye to detect any mistake on 24 Mahajan, V.D., Ibid., p. 13.

33

the part of his opponents. He was one of the first military commanders in

Asia to appreciate the value of artillery. As a diplomat, he seems to have

shown much more cunning and skill in dealing with the Afghans than with

his own people. The manner in which he played off the rebellious Amirs

(meaning commander and also governor) of Sultan Ibrahim aginst each

other was worthy of a Machiavelli25

It has rightly been pointed out by Dr. Tripathi that Babur combined

the vigour and hardihood of the Turks and Mongols with the dash and

courage of the Iranians. He was a fine fencer, a good archer and superb

horseman. He was never discouraged by efeats and he never shirked

from hard life. He loved action. In grave crisis and heat of battle, he was

resourceful. In strategy and tactics, he was undoubtedly much erior of

his opponents in India and Afghanistan. Whether he was a military nenius

or not, he was the best among the Indian generals of his day26

To quote Dr.Tripathi, "Without depriving Akbar of his well-deserved

greatness, it can be maintained that the seeds of his policy were sown by

his illustrious grand-father. The conception of a nqw empire based on a

political outlook as distinct from religious or sectarian, of the place of the

crown in the State, of setting the Rajput problem by alliances and

matrimonial contacts and of emphasizing the cultural character of the court

could be traced back to Babur. Thus Babur had not only shown the way to

find a new empire but had also indicated the character and policy which

25 lbld-,p. 18.

26 Tripathi R.P “Rise and Fall of Mughal Empire” pp 55-56.

34

should govern it. He had established a dynasty and a tradition in India

which have few parallels in the history of any other country.27

According to Prof.Rushbrook Williams, "Babur possessed eight

fundamental qualities - lifty judgment, noble ambition, the art of victory, the

art of Government, the art of conferring prosperity upon his people, the

talent of ruling mildly the people of God, ability to win the heart of his

soldiers and love of justice." According to Havell, "His (Babur's) engaging

personality, artistic temperament and romantic career make him one of the

most attractive figures in the history of Islam." According to Dr.Smith,

"Babur was most brilliant Asiatic Prince of his age and worthy of a high

place among the sovereigns of India."28

Lane-Poole has given the following estimate of Babur: "He is the link

between Central Asia and India, between predatory hordes and Imperial

government of Asia, Chingiz and Timur, mixed in his veins and to the

daring and restlessness of the nomad Tartar, he joined the culture and

urbanity of the Persian. He brought the energy of the Mongol, the courage

and capacity of the Turks, to the listless Hindu; and himself a soldier of

fortune and no architect of Empire, he yet laid the first stone of the

splendid fabric which his grandson Akbar achieved. His permanent place

in history rests upon his Indian conquests, which opened the way for an

imperial line, but his place in biography and literature is determined rather

by his daring adventures and preserving efforts in his earlier days, and by

the delightful memoirs in which he related them. Soldier of fortune as he

was, Babur was not the less a man of fine literary taste and fastidious

critical perception. In Persian, the language of culture, the Latin of Central

27 Ibid., p.61 28 Tripathi R.P Op., Cit., p 61

35

Asia, as it is of India, he was an accomplished poet, and in his native

Turkish he was master of a pure and unaffected style alike in prose and

verse."29

Malleson says that "By the rivals whom he had overthrown and by

the children of the soil, Babur was alike regarded as a conqueror and as

nothing more. A man of remarkable ability who had spent all his life in

armies, he was really an adventurer, through a brilliant adventurer, who

soaring above his contemporaries in genius taught in the rough school of

adversity, had beheld from his eyrie at Kabul the distracted condition of

fertile Hindustan and had dashed down upon her plains with force that was

istible. Such was Babur, a man greatly in advance of his age,

generous, ff tionate, [Ofty n njs views, yet in his connection with Hindustan,

but little more than a ueror. ^e nad no time to think of any other system of

administration than the system with which he had been familiar all his life

and which had been the system

introduced by his Afghan predecessors into India, the system of governing

by means of large camps, each commanded by a General devoted to

himself and each occupying a central position in a province. It is a

question whether the central idea of Babur's policy was not the creation of

an empire in Central Asia rather than of an empire in India.30

The same writer observes that Babur occupies a very high place among

the famous conquerors of the world. His character created his career

inheriting but the shadow of a small kingdom in Central Asia, he died

master of the territories lying between the Karamnasa and Oxus and those

29 Ibid p. 19, (Lane – poole.S. Babur, 1899). 30 Ibid p 19

36

between the Narbada and Himalayas. His31nature was a joyous nature.

Generous, confiding, always hopeful, he managed to attract the attention

of al with whom he came into contact. He was keenly sensitive to all that

was beautiful in nature. He loved war and glory, but he did not neglect the

arts of peace. He made it a duty to enquire into the condition of the races

that he subdued and to devise for them ameliorating measures. He was

fond of gardening, of architecture, of music and he was no mean poet. But

the greatest glory of his character was that attributed to him by Haidar

Mirza in Tarikh-i-Rashidi in these words: "Of all his qualities, his generosity

and humanity took the lead."

It is pointed out that what Babur had left undone was of greater importance

than what he had actually accomplished. According to Erskine, although

Babur's conquests aave him an extensive dominion, "there was little

uniformity in the political situation of the different parts of this empire.

Hardly any law could be regarded as universal but that of the unrestrained

power of the prince. Each kingdom, each province, each district, and (we

may almost say) every village, was governed, in ordinary matters, by its

peculiar customs.... There were no regular courts of law spread over the

kingdom for the administration of justice.... All differences relating to land,

where they were not settled by the village officer, were decided by the

district authorities, the collectors, the Zamindars (landlords) or Jagirdars

(governors). The higher officers of government exercised not only civil but

also criminal jurisdiction, even in capital cases, with little form or under little

restraint." Babur did not leave behind him any "remarkable public and

philanthropic institutions" which would win over the goodwill of the people.

No wonder, Babur "bequeathed to his son a monarchy which could be held

31 Ibid p 20

37

together only by the continuance of war conditions, which in time of peace

was weak, structure less and inveterate.32

Humayun and Shah Tahmasb ; After the death of Babur, his son Nasir-ud-Din Muhammad

Humayun was enthroned in the year 1530 A.D./939 A.H. Kamran Mirza,

Humayun's brother, who was the governor of Kabul and Qandahar during

their father's reign, rebelled and conquered Lahore and expanded his

realm. Thus, he physically stood between the governments of Delhi and

Qazvin. Therefore, during the first 13 years of the reign of Humayun there

were no contacts between Humanyun and Shah Tahmasb I and no

ambassadors were exchanged.

The two defeats that Humayun suffered at the hands of Sher Shah

Suri at the battles of Chausa and Qannauj forced him to seek refuge in

Iran 33 on the recommendation of Bairam Khan, Khan-i-Khanan, along with

fifty of his followers34

The story of Humayun's one year stay in Iran (1544 A.D./953 A.M.

including some three months' stay with the Shah), and the accounts of the

receptions, festivities and banquets held in Humayun's honor make

interesting reading, but the details need not detain us here. Two things,

however, stand out: that it was with the. unexpectedly extensive military

help of Tahmasbl that it was possible for Humayun to recover Qandahar,

which in turn became the stepping stone for the recovery of Kabul and

later, of Delhi. Secondly, Humayun's fine sensibility in the matter of art and

32 Ibid., p 20 33 Humayun in Iran see A.A. 'Abbasi, Op. Cit., 1955, Vol. II, pp. 96-100 and also see Wali Quli shnamlu,Qisas-ul-Khaqani, ed. By Hassan Sadat Naseri, Part I, Tehran, 1992, pp. 67-71. 34 For details see, Akbar Nama, pp. 163-169.

38

calligraphy35could not fail to impress the Persians; and several outstanding

Iranian artists, including Mir. Sayyid 'AH and Khwaja 'Abd-ul-Samad, joined

Humayun's service and eventually became instrumental in founding the

Mughal school of painting at Delhi. 36

Bayazid-i-Bayat collected a list of Humayun accompanies with their

positions in Iran is as follows:

on the way of come back to India, after capturing Bust 37, Humayun

marched to nandahar. Humayun's seizure of Qandahar from the Iranians

did not interrupt his friendly and cordial relations with Shah Tahmasbl. After

Humayun had conquered Kabul and established himself there, several

ambassadors were exchanged between the two kings. Shah Tahmasbl

sent Walad Beg Taklu as his ambassador to greet him for his victory. This

ambassador reached Kabul in the year 955 A.H./1546 A.D. He

participated in the battle which Humayun had undertaken at Badakhshan

along with Iranian soldiers. These soldiers who were the combat troop of

Shah Tahmasabl, displayed great valor in this battle38.

In the year 957 A.H./1548 A.D., Humayun appointed Khwaja Jalal-

ud-Din Mahmud, his Mir Saman (Steward, head butler), as his ambassador

to the court of Shah Tahmasbl but this ambassador, for reasons not

known, remained in Qandahar and thereafter returned to Kabul. A year

later, Humayun appointed Qazi Shaikh 'AH as his ambassador. This

35 Details see: Bayat Bayazid, Tazkira-i-Humayun va Akbar, Bib. Indica. Calcutta, 1941, pp. 68-69. K- 36 R.Islam, 1970, Op. Cit., p. 166; Brown Percy, "Indian Painting under the Mughals", Oxford, 1924, PP. 53-54. 37 Baayazid, 1941, p. 39, see also: Akbar Nama, Vol. I, p. 227. 38 Bayazid, 194! , pp. 64-65 see aso: Akbar Nama, Vol. I, pp. 249, 252, 259.

39

ambassador carried a letter from Humayun to Tahmasbl in which

Humayun companied of the mutinies of Kamran Mirza. In reply Shah

Tahmassbl advised Humayun not to be soft with his brother and offered

military aid. In the year 960 A.H./1551 A.D., Humayun sent another

ambassador, Khwaja Qazi to Tahmasbl. This ambassador remained in Iran

for two years. During this period Humayun sent a snort letter to Tahmasbl

in which he informed him Kamran Mirza's revolts and his failures.

At the time when Humayun was gathering his forces in Kabul for the attack

on india ambassador, Ulugh Beg came from Tahmasabl to his court. This

ambassador ht precious gifts for Humayun and Bairan Khan39. Ulugh Beg

was the last mbassador of Tahmasbl to the court of Humayun.

Relations between Akbar and Tahmasbl: In the year 1556 A.O./965 A.H., Humayun died in Delhi and his son

Jalal-ud-Din Muhammad Akbar succeeded him at the age of 14. Tahmasbl

attacked and conquered Qandahar which was at one time promised to him

by Humayun3540. This act offended Akbar and culminated in a course of

dissension between the two courts. In the year 971 A.H./1562 A.D.,

Tahmasbl designated Sayyid Beg Safavid, son of Ma'sum Beg one of his

relative, as ambassador to Akbar's court. This ambassador carried a letter

to Akbar conveying the condolence of Tahmasb on the Humayun death

and felicitations to the new emperor. In this letter Tahmasb referred to his

friendship with Humayun and the diplomatic mission of Khan-i-Khanan,

ambassador of Humayun41. As Khafi Khan related in Muntakhab-ul-Lubab,

the purpose of this letter was to nullify the offence taken by Akbar on the

39 Bayazid, 1941, pp. 173-175 see aso: Akbar Nama, Op. Cit., Vol. I, p. 335. 40 A.A. 'Abbasi, 1955, p. 92. 41 Badauni, Vol.II, pp. 40-41, and also see; 'Abd-ur-Rahim, "Mughal Relations with Persia" in: Islamic Culture, Vol. VIM, 1934, p. 466.

40

occupation of Qandahar by Tahmasbl. This ambassador also carried some

presents to Akbar. Akbar in return bestowed upon the ambassador

Rs.200,000, a richly caparisoned horse and a costly robe of honor42.

In the year 1564 A.D., Sultan Mohmud of Bhakkar sent a letter with

some gifts to court of Shah Tahmasbl. He requested that the Shah of Iran

recommend him to Akbar to grant him the designation of Khan-i-Khanan43.

Upon receipt of this request shah Tahmasb wrote a letter to Akbar and

recommended him. Based on this pcommendation Akbar granted Sultan

Mahmud with the title of "Etibar Khan" and wrote

letter to Shah Tahmasb informing him to this effect and also of the future

favors that he was planning for Sultan Mahmud.

Akbar and Shah Isma'il II:

In the year 985 A.H./1576 A.D., Shah Tahmasb died and his son

Shah Isma'il II succeeded him44. During his short reign Shah Isma'il II had

no diplomatic relations with Akbar, but wrote a letter to Mirza Hakim,

Akbar's brother, who was the governor of Kabul. In this letter Shah Isma'il

II called Mirza Hakim 'the king', and asked him to send his diplomatic

envoys to Iran. He also informed Mirza Hakim that the Ha/ pilgrims of

Kabul could travel by the Iranian routes.

Akbar and Khudabandeh:

42 M.H. Khafi Khan, Muntakhb-ul-Lubab, Bib. Indica, Calcutta, 1909-25, Vol. I, p. 143. 43 S.S.D. Shah Nawaz Khan, and 'Abd-ul-Hayy, "Maasirf-u!-Umara", Bib. Indica, Calcutta, 1885-95, Vol.IlI, PP 240-45 44 A.A. Abbasi, 1955 pp 213-214 and also see: Falsafi, N. Tehran 1955, Vol. I pp 30-33

41

After the death of Shah Isma'il //, in the year 986 A.H./1577 A.D., his blind

brother Sultan Muhammad-i-Khudabandeh45 was enthroned.

Khudabandeh, the eldest son of Shah Tahmasbl, when he was the viceroy

in Khurasan, in the year 981 AH/1572 A.D., sent Yar 'All Beg to Akbar's

court as his diplomatic envoy46 wind this, several diplomatic and cultural

envoys were exchanged. At that time the situation of the country was in

chaos and due to the disarray of the central government 47 the ottomans

incited the Turks on the western borders who began attacking Iran -in the

west48. Under these unpleasant circumstances Khudabandeh

dispatched Sultan Quit Chandan Oghll to Ma and requested Akbar's aid.

Akbar had in mind to send one of his sons to Iran to assist in curbing the

disorder. He even had a Khurasan in order to fight the Turks49.

While Iran was struggling along with these disasters, a new and graver

danger presented itself. 'Abd UHah Kahn-i-Uzbek, who had already

captured Balkh in the year 982 A.H./1573 A.D., occupied Badakhshan in

993 A.H./1584 A.D., invaded Khurasan and occupied a part of that

province50. 'Abd UHah Khan sent ambassador to Akbar and suggested that

together they attack Iran, so that the rule of the impious (Shi'as); should

end and the road be opened to pilgrims to Mecca and Medina. He also

suggested that Qandahar should once again be a part of India's territory51.

In his reply to 'Abd Ullah, Akbar stated that the Safavid were the

45 The Enc. Islam (New edn) ascribes (Inaccurately the blinding of Khudabanda to 'Abbasl), A.A. 'Abbasi, Op. Cit., p. 126 which says he became blind during his boyhood. 46 Akbar Nama, Vol. II, p. 8 and also see: S.H. Elliot, and J. Dowson, History of India as told by its own Historians"., Vol. V, London, 1867-75, p. 342. 47 AA'Abbasi, 1955, pp. 222-28 and also see: Falsafi, N, 1955, Vol. I, p. 53. 48 A.A. Abbasi, 1955, pp. 230-235 and also see: Falsafi, N., 1995, p. 147. lslam, 1970, p. 51. 49 lslam, 1970, p. 51. 50 See : Sir H-H. Howorth, "History of Mongols", London 1876-1927. 51 Akbar Nama op Cit. Vol II P 368 Tr by H. Beveridge p 534

42

descendants of the Prophet and therefore were not impious52. He told 'Abd

Ullah that by conquest of Gujarat by him (Akbar) the sea route was open to

pilgrims and that the Turks could use this route53. In regard to the

return of Qandahar to Hindustan, Akbar wrote to 'Abd Ullah that since the

governors of Qandadhar were a friendly terms with him and had not

molested Indian caravans, he ild see no reason to attack Iran and take

Qandahar back. Thus, with this firm and oble attitude, he rejected all the

proposals of 'Abd Ullah54,

Akbar and Shah 'Abbas I:

Shah 'Abbas I formallyeascended the throne in 997 A.H./1588 A.D.

He was in a difficult position with pressure from the Ottoman Turks in the

west and with the Uzbeks in occupation of Khurasan. He sent Yadgar 'AH

Beg Rumelu55 as his ambassador to the courtof Akbar (1591 A.D./1QOO

A.H.), principally for purpose of seeking Mughal support against the

Uzbeks; 'Abd Ullah Khan of Uzbeks occupation of Khurasan and Uzbek's

activity in the Mughal frontier region, were no less worrying for Akbar, who

stayed for about fourteen years in the Punjab to keep a watch on the

frontier. Placed thus, Akbar had to conduct his foreign relations cautiously.

Hence for a good while he discouraged 'Abd Ullah Khan-i-Uzbek's

proposal for a joint Mughal-Uzbek invasion of Iran (1577 A.D./986 A.H.)

and when later, he signed agreement (1586 A.D./995 A.H.) he did so to

52 Ibid Vol III, p 297 53 R Islam, 1970 p 52 quoted it is matter of curious interest to receall Mulla Badauni’s story that Makhdum-ul-Mulk, Akbars Shaikh-ul-Islam gave a legal injunction against proceeding on piligrimage to Mecca through Persia on the ground of the country being in Shi it hands. Badami, Vol II, p. 203 54 R. Islam Op., Cit., p. 29 55 Also Called Shamlu, A.A. Abbasi, 1055, A.H., p.314, p.291, Falsafi.N.1955, Vol. I, p.218

43

keep the Khan humored fully knowing that the contingency of such a

Mughal-Uzbek invasion was hardly ever likely to occur56.

Akbar's real interest was in the recovery of Qandahar, for which he awaited

a uitable opportunity57. Finding that they could not save it from the

burgeoning Uzbek

Power and losing hope of support from the Shah in distant Qazvin, the

Iranian governor of the fort Rustam Mirza and Muzaffa Hussain Mirza 58sons of Sultan Hussain Mirza Safavid gladly handed it over to Akbar's

men and accepted high Mansab (post, employment) for themselves in the

Mughal court59. Akbar had detained the envoy of Shah 'Abbas, Yadgar 'AH

Beg Rumlu for more than four years60. It is significant that the envoy was

not given leave to go back till the acquisition of Qandahar had become a

certainly. Along with this ambassador Akbar dispatched Mirza Zia-ud-Din

Kashi, as his ambassador to Iran61. In return Shah 'Abbas! dispatched

Manuchehr Beg, Ishik Aqasi Bashi62 to India bearing precious gifts63. This

emissary arrived at the court of Akbar in Lahore in the year 1598

A.D./1007 A.M. and was warmly welcomed64. As requested by Akbar,

Shah 'Abbas in his letter informed him in detail of the complicated status of

Iran, the disputes among the Qazilbashid tribes and the attack in the

western zones of the Iran by the Ottoman Emperor.

56 Encyclopedia of Islam, 1993, Vol VII. P.317. 57 58 Akbar Nama, Vol. Ill, p. 117. 59 See: Notices of their careers in:M.U., Vol. Ill, pp. 269, 423. 60 A.N. Vol. Ill, pp. 645-46, 669, see: Tabaqat-i-Akbari, Vol. II, p. 423. 61 R.lslam, 1970, p. 61. Quoted in Akbar Nama, Vol. Ill, p. 588, According to A.N. The Persian envoy arrived at the Mughal court in 999 A.H. and left in 1033 A.M., the 'A/am Ara, 1935, p. 361, says that he left Iran in 999 A.H. and arrived back in 1005 A.H. Ibid., quoted in A.N., Vol. Ml, p. 656, names them Zia-ul-Mulk and Abu Nasr-i-Khwafi, and notes that both Iranians; see: 'Abd-ur-Rahim, Islamic Culture, Voi. VIII, 1934, pp. 471-472. 62 Grand Usher, or Lord of the Gate. 63 For details see: Falsafi, N, 1955, Vol. I, pp. 232-234 and also see: A.A. 'Abbasi, 1955, Part I, pp. 543-544 64 A.M., Vol. |||, p. 745

44

During the stay of this ambassador in India, fortune favored Shah 'Abbasl.

Both 65Khan of Uzbek and his son 'Abd-ul-Mumin Khan died66. Their

deaths paved way for the way for Iran to regain the crctropreo1 parts of

Khurasan. In the year 1598 A.D./ 1007 A.H. Shah ‘A.H. Shah Abbasl

conquered Herat61 and he wrote a letter to Akbar giving details of his

victory and also expressed the hope for the return of Qandahar to Iran67.

Manuchehr Beg, the Iranian ambassador returned to Iran in the year

1602 A.D./1011 A.H., with gifts for the Shah and Rs.10,000 for himself.68

During the siege of Yerevan, Mir Ma'sum Bhekhari69 a prominent scholar,

was sent by Akbar in 1602 A.D./1011 A.M.,70 to Iran with precious gifts.

Shah 'Abbasl received this ambassador warmly at the battlefield71. In the

letter that Mir Ma'sum brought, Akbar lauded Shah 'Abbas I for his victories

over the Ottomans in the west and the Uzbeks in the east. Meanwhile, he

informed the Shah of Persia of his own victories at Asirgarh and in the

south of India72.

Mir Ma'sum returned to the Mughal court in the early 1605 A.D./1014

A.M. He brought with him a letter from the Shah for Akbar, describing the

Iranian victories of yerevan and elsewhere. Mir Ma'sum also brought a

65 A,A, Abbasi, 1955, Part I, pp. 553-558. 66 Ibid., pp. 569-570. 67 Ibid., pp. 405, 683, and also: A.N., Vol. Ill, p. 749 makes no mention of the request for the restoration of Qandahar. 68 A.M. Vol.lll, pp. 787, 815. 69 For Mir'sum see: M.U., Vol. Ill, p. 326. 70 A-N., Vol.lll, pp. 825-827, Azar, 47th R.Y. f Shah 'Abbasl the author of A.A.'Abbasi says that Mir Ma sum arrived with Manuchehr. But the A.Ns. careful chronology makes this unlikely. (See: A-A.'Abbasi, p. 338) 71 Ibid 1935, pp. 448, 455. 72 For regarding the entertainment of Shah 'Abbasl to Mir Ma'sum see: A.A.Abbasi, op. cit, pp. 647-648.

45

letter from Shah's aunt to Akbar's then Maryam Makan Begum(Himida

Banu Begum) 73.

73 Abd-ur-Rahim, Mughal Relations with Persia” in: Islamic Culture Vol VIII, 1934 pp 472-473 and Also See R. Islam, 1970 p.111quoted in A.N., Vol III p.836

46

Jahangir and Shah'AbbasI: As prince, Jahangir had been on very friendly terms with Shah

'Abbas through envoys, letters and messages. But his reign opened with

an attempt by the Iranians to occupy Qandahar and this created a

deterioration in the relationship between the two empires74. The death of

Akbar and the revolt of Khusraw gave Shah 'Abbas I the opportunity of

instigating he chiefs of Khurasan to attack Qandahar; but Shah Beg Khan,

the Indian governor of the fortress, put up a stout defense. Early in 1607

A.D./1016 A.M., Jahangir sent reinforcement under Mirza Ghazi Tarkan75.

The Iranians were struck with terror, raised the siege and retreated to

Khurasan. Foiled in this business Shah 'Abbas! disclaimed knowledge of

the invasion, rebuked the Khurasani nobles and apologized to Jahangir.

He wrote to explain that the restless border tribes had committed the

mischief of their own accord and that he had punished them for their

foolish audacity76. Shah Abbasl sent Hussain Beg to Jahangir, in order to

clarify the Qandahar incident77. In reply which Jahangir sent by Hussain

Beg to Shah 'Abbas I he complained of delay on the part of the Shah in

opening regular diplomatic relations and noted that the dispatch of a major

Iranian ambassador had been further postponed78. It the 6th year of the

reign of Jahangir (in 1610 A.D./1019 A.M.) that the formal ambssador of

Iran, Yadgar Sultan 'AH Talish, a former governor of Baghdad and an

scholar, was sent to India79. Shah 'Abbas I in his letter to Jahangir, which

was carried by this ambassador, expressed his condolences on the death

of Akbar arid, added his congratulations on Jahangir's ascending the

74 Jahangir, Tuzuki-i-Jahangiri, Aligarh, 1869 p.349 75 About relationship between Mirza Ghazi and Shah ‘Abbasl, See : Sayyid Mir Muhammad, Tarkhan Nama, ed., S. Hasam0ud0Din rashdil, Hyderabad, 1965, pp 91-92. 76 A.L, Srivastava, 1989 p.260 Bani Prasad, pp 147-48 77 A.A. Abbasi, 1935 p.693 Tuzuki p.53 78 R.Islam 1970 p.70, quoted from Bhag Chand Munshi : Jami-ul-Insha.B.M., or 1702, ff.230b-232b. 79

47

throne of India80. The royal letter cited the campaigns of the Shah in the

western provinces as an excuse for delay in sending a regular

ambassador81. He returned with honors and rewards in August 1613

A.D./1022 A.M. to accompany the Mughal envoy, Khan-i-'Alam to. Iran82.

Duri.rg the two and a half years stay of Yadgar Sultan 'All in India, there

were further diplomatic exchanges between the two monarchs83. In

one of these, Shah sent a note recommending one Salam Ullah Arab for

promotion. Jahangir at once increased his Mansab and Jagir

(Governorship)84.

The pattern of subsequent diplomatic relations is an almost one-

sided succession of envoys and emissaries from Iran to India. Jahangir

sent only one major emissary, but the Shah dispatched two major (besides

that of Yadgar Sultan): arid numerous minor envoys. The purpose of these

numerous missions was to ally all apprehensions on the score of Iranian

interest in Qandahar and to build up a relationship of confidence and

trust with Jahangir85.

Besides political relation between Jahangir and Shah 'Abbas, there

were ommercial and trade connections between them. The first mission of

this kind was sent by Jahangir some years before his accession. His agent

was a trader, Khwaja Burj 'All Nakhjavani with the title crf^Zubdat-ut-Tujjar

(skilled trader). Shah 'Abbas intervened and supplied his requirements

80 A.A. Abbasi, 1955, p. 782 81 Ibid., about gifts of Shah ‘Abbasl to Jahangir by Sultan Ali Talish, See : Ibid p. 783 82 R. Islam, Ibid., 1970 quoted in Tuzuk, Op, Cit., pp 94-95, this letter is purely congratulatory, a condolatory, Letter given in the Mushaat-i-Tusi, ff.158a-59a, and claimed by the compiler as his own compsotion, was also brought by the same envoy, this second letter is also given in Abul Qasim Haider Beg Iwagli, Nuskha-i-jamia Muraselat-ul-Alab, A collection of letters to and from the Shahs of Persia, B.M. Add, 7688, also or 3482, f 214ab 83 A.A. Abbadi, 1955, p.939 84 This refers to the missions of Chalabi Beg from India and Uwaisi Beg from Persia. 85 R. Islam, in the Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol,. VII, 1993, p.317

48

from the royal stores, and wrote a letter to Jahangir (i.e., the then Prince

Salim) complaining why he should have entrusted his needs to traders

rather than have written to him directly. Shah 'Abbas sent this letter

through Khwaja Muhammad Baqir an Indian trader who seems to have

been in Iran for trade purposes86. In the year 1613 A.D./1-22 A.H.,

Jahangir decided to send a connoisseur of jewels, Muhammad Husain

Chalabi, to Turkey to buy certain jewels. Since he had to go to Turkey via

Iran he brought a letter and some gifts for Shah 'Abbasl. When Shah saw

the list of the jewel requirements of Jahangir he assigned Uwaisi Beg

Tupchi to procure these articles and later on sent him with these and a

letter to India, Muhammad Hussain-i-Chalabi's mission is referred to at

length in the Shah's letter brought by Muhammad Reza in 1027 A.H./1618

A.D. and recorded by Jahangir in his memoirs87. One of the articles (says

the letter) on Chalabi's list was a set of Jewels one of which was engraved

with the names of Jahangir's ancestors. According to religious

endowments these rubies belong to the Shrine of Najaf. However, the

rubies under Question were taken back following a request by the religious

leaders. "Since the jewel box', the letter mentions, "prepared by Chalabi

was not worthy of your Majesty. Shah 'Abbas ordered his artisans to

prepare a jewel box deserving Your Majesty's dignity. Insha-Allah after its

completion, I will send the rubies to you in this box"88.

At Jahangir's request, the Shah also sent the original astrolabe of

Ulugh Beg, the celebrated Trumirid Prince89, keeping for himself only a

copy. In 1615 A.D./1024 A.M., he dispatched Khwaja 'Ab&ul-Karim-i-Gilani,

an Iranian trader, with a letter and with certain rarities asked for by 86 R. Islam, 1970 p.71 87 Tuzak, pp.165-166 88 Falsafi.N.1961, Vol VI, p.87 89 Ulugh Beg, Timurid Prince and astronomer, died 853 A.H/1449 A.D., was son of Shahrukh, Timur’s son and Successor

49

Jahangir. The Khwaja is described therein as a trusted servant of the

court, and Jahangir, is requested to appoint his own agents to assist the

Khwaja. Another Iranian trader, Muhammad Qasim Beg came, probably

with the Iranian ambassador Muhammad Reza Beg, on a commission from

the Shah90.

It may be added here that Prince Shahjahan also sent purchasing

agents to Persia, Turkey and the Middle east. These agents catered

almost exclusively for royal requirements, most of which in the nature of

rarities; horses of superior quality for display purposes were also in

demand at the Mughal Apart from the venture of royal agents some private

traders also received royal patronage. One Haji Rafiq, for instance, went to

Iran a number of times and made himself known to Shah 'Abbas.

Appreciating his initiative and tact, Jahangir conferred on him the title of

Malik-ut-Tujjar, Haji Rafiq carried letters between the Shaha and

Jahangir91

The Great Ambassador of India:

Jahangir assignedM/rza BarkhordarKhan, whose title was Khan-i-

'Aiam; from the tribe of Barlas and one of his close relatives, as his first

ambassador and sent him to Iran in the year 1618 A.D./1027 A.M. with a

variety of precious gifts92.

The embassy of Khan-i-'Alam is a very important landmark in the history of

Muahal diplomacy, for never before or later was a more splendidly

equipped mission sent out93. Khan-i-'Alam was much cherished by

90 R. Islam, 1970, p.73, quoted in Tuzuk, p166, Qasim Beg was a brother of Muhammad Hussain-i-Chalabi 91 R. Islam, 1970p. 73, quoted in Tuzuk, p.223, and also : Falsafi, N. 1960, Vol Iv, P. 295. 92 Tuzuk, Op, Cit., p. 121 93 M.UI. Text, Vol., I. P. 782

50

Jahangir, who addressed his as brother. He was the most important envoy

sent to the court of the Safavids. This ambassador stayed in Heart, later at

Qom before coming to Qazvin. The embassy was meant to strike the

imagination of the Iranians, but was also aimed at impressing 'Abbas with

the wealth of India as well as the warmth of feeling Jahangir entertained for

him. The impression it created in Iran is recorded by Iskandar Beg-i-

Munshi, Pietro Delia Valle (Italian traveler), Shah Hussain Malik Ghiyas-

ud-Din Muhammad (nobleman of Sistan) and author of the Ihya-ul-Moluk,

who witnessed its entry into Qazvin and Isfahan94. Iskandar Beg says that

no embassy like this had ever come to Safavid court since the foundation

of the dynasty. Besides at least a thousand servants, a number of painters

such as Bishan Das95, Khairat Khan and Likraj wee also members of the

Indian ambassador's cortege. They came to Iran to paint the portraits of

Shah 'Abbasl and his courtiers. A number of these portraits which are

extant today are the masterpieces of ne works of these painters. Mohsen

Fani Kshmiri, a great writer, also came with Khan-Alam to Isfahan in the

capacity of a chronicler. He used to prepare the news of Shah Abbas

court and dispatch it to India.

In the year 1620 A.D./1029 A.M. after a two year sojourn in Iran, the Indian

. diplomatic mission returned to its country. Khan-i-Alam with his excellent

behavior made a very favourable impression on Shah 'Abbas which

prompted the Shah of Persia to call him "Jan-/-Wam"96 [Spirit of the World].

This ambassador successfully completed his mission and upon his return

to India was warmly welcomed by Jahangir and was rewarded by being

94 For details about reception of Khan-i-Alam in Iran. See : A.A. Abbasi, 1955, pp.939-940=, 951 Pietro Della Valle, Vol IV, PP 243-247, quoted from Falsafi N, 1960, Vol. III, p. 278-280, Iyhya-ul-Muluk, ff213a-15a, Falsafi, N.1939, pp.56-61, M.U., text, Vol.,I p.737 95 For Bishan Das See : Percy Brown, 1924-pp.82-126. 96 M.U. Text, Vol I p. 734, Kahfi Kahn Vol II. P. 202

51

promoted to 5000 Zat (soldier) and 3000 sawar(horseman), and in 1621

A.D./1030 A.M. appointed him governor of Allahabad97.

Mission from Persia:

When IKhan-i-'Alam was in Iran, several envoys were dispatched to

India by Shah Abbasi, Robert Sheriey was the first envoy who came to

India. He was the Englishmen, who strangely spent thirty years of his life in

the service of the Iranian king. He came to Jahangir's court in 1614 A.D/1-

23 A.H., on his return from a round of diplomatic visits to the Christian

Princes of Europe, and was well received and set on his way with two

elephants and eight antelopes as presents to the Shah98. The second

envoy of Shah 'Abbas-l to India was Mustafa Beg in the year 1615

A.D./1024 A.H. He carried a letter from Shah to Jahangir which contained

a report of the victories of the of Iran over Georgia. Among the presents

sent with Mustfa Beg were several

European hunting dogs that Jahangir had wanted. After a few

months' stay in India he d to (ran with Jahangir's letter and presents99. A

few months after Mustafa , departure, another ambassador Muhammad

Reza Beg Shamlu arrived in Novvember 1616 A.D./1023 A.M., with

presents and a letter from the Shah100. Sir Thomas Roe, English envoy

97 Iqbalnama-i-Jahangir.p.134 see also : M.U. Text Vol. I p.735 98 Clara Cary Edwards, Relations of Shah Abbads the Great of Persia, with the Mughal Emperos, Akbar and Jahangir, in Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol 35, No.1, 3, 1915, p 155; and also see Falsafil, N. 1939, p.42. 99 Abd-Ur-Rahim, Mughal relations with Persia’ Islamic Culture, Op. Cit., 1934, p. 655, Hadi Hasan, Collection of Articles, Hyderabad Deccan, 1954, p.40 100 Islamic Culture, 1934, pp.655-56; quoted Jami -a -iMurasilat, F.217 for the letter

52

at the Mughal court, has recorded an interesting and detailed account of

this ambassador101.

It is not clear as to whether the embassy of Muhammad Reza Beg

had any special purpose, apart from those stated in Shah 'Abbas's letter.

Roe heard reports that the envoy had ostensibly come only to ensure

peace between the two empires on account of the Deccan but that his real

aim was to obtain monetary aid for his master in his wars against the

Turk102. Beni Prasad thinks that Muhammad Reza's embassy had

something to do with Qandahar103. But no reference to this question was

made by the Shah till after Khan-i-'Alam's return to India. He was

dispatched at Mandu with ample rewards on the 3rd Rabi'-ul-Awwal

A.H.1026/ApriI 1617 A.D."104 On his way Muhammad Reza105 died at Agra

and Jahangir ordered all his goods to be handed over to Muhammad

Qasim Beg, an Iranian merchant106.

Jahangir had sent a cup for Shah 'Abbas with Muhammad Reza,

and the Shah 'Abbas in return sent a crystal goblet and a letter giving an

account of recent Iranian victories with Sayyid Hussain on the 27lh Rabi'-ul-

Awwa! 1027 A.H./March 1617 A.D.107 Shah 'Abbas, who was always

desirous of designating an ambassador to India bearing equal standing

and dignity of Khan-i-'Alam, appointed Zainal Beg108 and dispatched him to

101 Sir Thomas Roe, The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe, Ed., By Sir W. Foster, O.U.P, 1926 pp258-260 300-301, 350-351. 102 S.T. Roe, 1926, pp258-250 103 Bani Prasad 1962, p.345, see also : Aqbalnama, pp.89-90 104 Roe, Ibid, 1926, pp363-64, about gifts and rewards see : J.A.O.S, 1915, pp.256-57 105 For details 106 R. Islam 1970 p.77, quoted from Tuzuk, op.cit., p.197 107 Islamic Culture, 1934, p. 656 but R. Islam has mentioned Sayyid Hassan in Shawwal 1026 A.H./Oct. 1617A.D., see; R. Islam, 1970, p. 108 Zainal seem to be the correct form of the Nama; see; A.A. 'Abbasi, 1955, pp. 950, 993 and see aiso, w Falsafi,N, Op. at, p. 109. It has been written as Zambil in the Tuzuk, pp. 289

53

India with gifts from himself and other Iranian nobles109. He reached

Lahore in the summer of 1622 A.D./1031 A.M.,110 when Jahangir was in

Kashmir111. Jahangir on learning of his arrival, sent Mir Hisam-ud-Din, son

of Mir 'Aziz-ud-Din, to Lahore to meet Zainal, and gave orders to the

governor to bear all the expense of the ambassador. Zaina! Beg presented

his credentials in November112when Jahangir returned to Lahore. Besides

gifts, the ambassador also presented two gentlemen of his entourage.

Wisal Beg and Hji Ni'mat, who were courtiers of the Shah113. The mission

of Zainal Beg coincided with the dispute regarding Qandahar. He

continued to press his point about Qandahar with the Mughal authorities

but without success. According to '/A/am Ara, Zaina! Beg was unbending

at the Mughal court and firmly refused to offer court salutation in the

Mughal custom114. While Zaina! Beg was in India five other envoys were

dispatched by Shah 'Abbas to India with fetters and presents115. The first

envoy Were Aqa Beg and Muhibb 'All.116 Among the presents they brought

was a ruby from rolleclion of Mirza Shahrukh bin Amir Timur. Ulugh Beg's

name was engraved on . ruby and the Shah also had his

name117engraved in a corner. As this was a pcious heirloom, it was much

appreciated. It seems that Gilan horses and some ornaments and

clothes were sent by the Shah118.

109 AA 'Abbasi, 1955, p. 951. 110 A-'Abbasi, 1955, p. 993. 111 : A.A.'Abbasi, 1955, p. 951. 112 About gins of Shah to Jahangir see 113 A Rahim, "Mughal Relations with Persia" in: Islamic Culture, 1934, p. 658, quoted from, Tuzuk, Vol. II, 109 p-186-,,Q 114 A.A.'Abbasi, 1955, p. 994. 115 These envoys have not been mentioned in A.A.'Abbasl. 116 R.Islam, A Calender of documents of Indo Persian Relations” 1979, Vol. I p.202, Karachi. 117 Banda I shah 0 wilayat Slave of Ali Ibn I Abu Talib 118 A. Rahim, “Mughal Relations with Persia in : Islamic Culture 1934, p.658 for the account of this Embassy see: Saqi Musta id Khan, Maasir-i-Almgiri, Bib, Inica, Calcutta, 1947, f.143.

54

While this mission was still in India, another embassy under Ha/7

Beg and Fazl Beg arrived with a letter and presents from Shah 'Abbasl.

These envoys were dismissed in the end of Rabi'-ul-Awwal 1030 A.H/1621

A.D.119

Scarcely had these four envoys departed when another envoy,

Qasim Beg appeared with letter and presents from the Shah. The Shah

had asked for some birds, which were sent with the ambassador when he

was dismissed in January, 1622 A.D./1031 A.M. While these ambassadors

came and went, Zainal Beg continued to reside at the court120.

Jahangir, on coming to know of Shah 'Abbas's request for

Qandahar, consulted his advisers. The chroniclers during the reign of

Shahjahan claim for him the credit of advising Jahangir to reject the Iranian

request121. In any event, the opinion that finally prevailed was that the

surrender of Qandahar would be regarded as a sign of weakness. This is

confirmed by the Persian sources as well, for they say that a group mischief-

makers at Jahangir's court prevented the settlement of the issue in sordance with

the Shah's desire122. Zainal Beg, then at the Mughal court, kept the lah informed

of the position123. He sent also reports of movements of troops, racially the

dispatch of large Mughal forces to the Deccan under Shahjahan to deal nth

renewed trouble organized by Malik 'Ambar124. It can safely be presumed that

his {reports also covered the internal political situation of the empire and the

factious : intrigues at the court. There can be little doubt the news of that internal 119 Ibid. f 147 120 Tuzuk (Rogers trans) Vol II, p.211 121 R. Islam 1970 P.81, quoted from A. Lahori Padshah Nama, Bib. Indica, Calcutta, 1867, Vol II. P.25, and also See : Khafi Khan’s Vol I P.325-26, 343 Khafi Khans statement that Nur Jahan and Asaf Khan advised accourance of the Shah’s request, lacke confirmation, earlier sources. C.F, Maasir – i- Jahangiri, F.1736. 122 AA.'Abbas/, 1955, p. 961. 123 AA'Abbasi, 1935, p. 700. 124 R. Islam, 1970, p. 81, quoted from Lahori, Vol. II, p. 26, For details, see;Tuzuk, p. 322.

55

political position of India reached Shah 'Abbas/ regularly through his

ambassador and frequent emissaries as well as through other informants, and

encouraged him to decide on marching to Qandahar and choose his own time for

it125.

In the year 1622 A.D./1031 A.M., Shah 'Abbas conquered Qandahar126

Jahangir's attempt to form an alliance with the Uzbeks and his plans to send an

expedition under prince Khurram (Shahjahan in future) for the recovery of the

fortress, all came to naught 127

After the conquest of Qandahar, Shah 'Abbas sent Haidar Beg and

Wali Beg Darugha (magistrate) of Shotor Khan as emissaries to India, in

order to clarify any ^understanding and check offence on the part of

Jahangir128.

The Shah's defence of his action agrees with that recorded in the

'Alam Ara-i-Abbas /. When his frequent request to cede Qandahar was

repeatedly ignored, he decided to pay a friendly visit to the fort to

demonstrate to the complete accord of the empires, but on the stupid

refusal of the commander of the fortress to admit him as honoured guest,

he had no choice left but to force an entry and take the Qandahar ably.

The letter closes with the remark that their mutual friendship was too firmly

jnded to be affected by minor events129.

125 R Islam, 1970, pp. 81-92. 126 A.A. 'Abbas/, 1955, p. 994; and also see: Sabetian Zabih Ullah, "Historical Letters and Documents of Safavid Period", Tehran, 1964, p. 312. 127 Tuzuk, pp. 345, 352; Maasir-i-Jahangiri f. 173b 128 A.A Abbas/, 1955, p. 994; and also see: Sabetian Zabih Ullah, "Historical Letters and Documents of ';Safavid Period", Tehran, 1964, p. 312. 129 R. Islam, 1970, p. 43, For Shah's letter and Jahangir's reply see: Tuzuk, pp. 348-352. It refers to the Keys of the kingdom of Iran being sent to Jahangir which is also mentioned in A, A. 'Abbasi, 1935, p. 686, lines 9-10, For details of letter see: R. Islam, Ibid., 1979, Vol. I, pp. 205-209.

56

Jahangir sent a reply to Shah with the retiring Persian envoys130.

He indicated his surprise at the hasty action by Shah in conquering

Qandahar. He pointed out that Shah'Abbas should have awaited the

return of Zainal Beg131. However, in this letter Jahangir stated that the

friendship between the two empires is much stronger than to allow a

matter such as Qandahar to injure it132. Shah 'Abbas made every effort to

conciliate Jahangir and to assuage the other legacy of bitterness over

Qandahar. So he wrote to this effect to other influential personage like

Prince Khurram, Nur Jahan and Khan-i-'Alam133.

While Shah 'Abbas was still at Qandahar, Prince Khurram's

ambassador Zahid Beg appeared with letters134 and presents an act which

cannot be explained in any way, for so far Jahangir had taken no action

against Shahajan. The Shah treated the ambassador very kindly and

dismissed him with a reply to the letter he had brought135. Another letter

was sent by Prince Khurram to Shah 'Abbas with Khwaja Haji136 at the time

of his retreat to the Deccan in 1622 A.D./1031 A.M. This was an open

appeal for help, for he says, "I too have like my forefathers turned to you

130 R. Islam, 1970, p. 83, and Falsafi. N., Ibid., Vol. IV, Tehran, p. 105, of the of the dismissal of Za/naf Beg, the Principal Iranian envoy, there seems to be clear mention in the Tuzuk which merely says (p. 348} that all the envoys that had come from Shah 'Abbas at short intervals were given robes and expenses (Khilat va Kharji) and were dismissed at Lahore on Azar Month, 17th reign year. (The month and the year corresponding to November, 1632 A.D.), Zainal Beg was evidently one of them. The 'Abbas/, p. 994, says that Jahangir became angry with Zainal Beg on account of Qandahar affair, iter suitably dismissed him along with the other Iranian envoys, 131 Tuzuk, pp. 350-352, and also : R. Islam, 1979, Calendar No.91. 132 A.A.'Abbas/, 1935, p. 700, 133 R.Islam, 1970, p. 84. 134 For letters of Prince Khurram to Shah 'Abbas see: Majmu'a (Collection), Tehran University Central Library, Ms. 2591, pp. 89-90, For second letter see: Ibid, Ms.2591, f.87, for reply from Shah to Khurram, see: Ibid, Ms. 2591, f. 90. 135 For details see: A.A.'Abbasi, 1955, pp. 976-977. 136 For letter of Prince Khurram to Shah'AbbasI by Khwaja Haji see: Falsafi.N, 1960, Vol.IV, pp. 110-111,

57

help with hope that you will give me proper aid at the proper time". But the

Shah, whatever encouragement he might have given to Zahid Beg now

advised Khurram to be loyal to his father, and said: 1 am sending an

ambassador to Jahangir to recommend your case."137 One letter was also

sent by Shah to the Prince Khurram138 with IsHaq Beg-i-Yazdi,139 Mir

Saman of Mumtaz Mahal in 1627 A.D./1-36 A.M. In this letter Shah says:

The supreme thing in life is love and affection. The relation of love

between the father and the son has been resorted, expressing joy and

gratitude at this and hopes that the prince wills perservere : in seeking his

father's pleasure.

In the year 1627 A.D., Aqa Muhammad Mustaufi-i-Ghulaman140 was

sent to India a letter141from Shah 'Abbas in which he reported his victory

over Baghdad142. jme of the booty from Baghdad was sent to Jahangir

also. The ambassador was received by Jahangir in Lahore in October,