Capoeira Wheel

description

Transcript of Capoeira Wheel

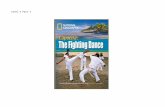

The n’golo, or dance of the zebras(Neves e Souza, c. 1960s)

CAPOE I RACI RCLI NG I N TH E WH E E L OF LI FE

CAPOEIRA (kah-PWEH-dah) is an Afro-Brazilian art form that combines aspects of ritual, dance, street fi ghting, acrobatics, music, cunning, and playfulness. The practice has been deeply infl uenced by the African experience in Brazil, dating back at least to the 18th-century colonial era, and perhaps far earlier. However, because it has largely been passed down from one practitioner to another, few outsiders have had access to the secrets of capoeira until relatively recently. As a result, its history is riddled with complexities and contradictions that are only just beginning to be unraveled. This article should therefore be read as a preliminary, and evolving effort to bring together the “hard” facts of historical research with the oral—and bodily—history of capoeira, as learned through the author’s own research and training in the form.1

AFRICAN ORIGINS

An important precedent for capoeira may be found in a little-known tradition of African “dance-fi ghting.” Dance-fi ghting is still practiced by some isolated Bantu-language communities in West Central Africa, ranging from the southern highlands of Angola, north to the river Congo. In traditional African societies throughout this region (and indeed, much of Africa), it is common for rites of passage, celebrations, religious rituals, and even military training to be weaved into community life through music, storytelling, and movement.

In extreme southwestern Angola, one group of people (ethnographically categorized as Nyaneka-HumbeNyaneka-HumbeN , or informally as “Bangala”) perform a kind of two-person “challenge dance” called the engolo.2 Often cited by capoeira practitioners as a likely antecedent of capoeira, the engolo is still performed as part of formal initiation or marriage ceremonies.engolo is still performed as part of formal initiation or marriage ceremonies.engolo It may have also been used in the training of warriors, or as an informal, playful way to keep the refl exes sharp. Inspired by the fi ghting style of zebras, the engolo (and similar forms throughout the area) engolo (and similar forms throughout the area) engoloconsists mostly of kicks, sweeps, and headbutts meant to humiliate, but generally not disable, an opponent. The lack of hand strikes may partially be explained by a proverb in Kikongo (a nearby Congolese language) that says that “hands are to build, feet are to destroy.”3 This kind of foot-fi ghting tradition, transplanted to the Americas along with many other African cultural practices, may have eventually became known in Brazil as the jogo de capoeira. To understand how it came to be that so many Africans were taken to Brazil, however, we must investigate the early years of Brazil’s colonial history.

THE BRAZILIAN CONTEXT

Upon the rather uneventful landing of a Portuguese fl eet on the Northeast coast of Brazil in 1500, the vast country (equal in size to the lower 48 United States) did not seem to offer the seafarers any obvious riches or civilizations to spoil. The local Tupi peoples, hunter-gatherers who engaged in constant warfare against their neighbors (including ritual cannibalism), did not possess gold or build impressive cities, such as those the Spanish would soon topple in Mexico and Peru. The Tupi did, however, possess an encyclopedic knowledge of their own land (which they called Pindorama, or “Land of the Palm Trees”), enabling them to help the Portuguese harvest a tree that produced a valuable red textile dye. This wood, called pau brazil,would eventually give the country its name. Nevertheless, even with such a lucrative trade in dyewood, the Portuguese lacked the resources and desire to colonize the country, so they focused their efforts on continuing their growing monopoly over the African slave trade, and trading routes to the Far East.

With ambitious Portuguese navigators leading the way throughout the late 1400s, trade routes from Europe to Asia and the New World opened a new kind of global economy. The introduction of exotic new concoctions such as tea, coffee, and cocoa in Europe also created an unforeseen need for sugar to sweeten these usually bitter drinks. Sugarcane did not grow well in the European climate, however, so the Portuguese established plantations (or engenhos) engenhos) engenhoson the African islands of São Tomé and Príncipe. When these proved wildly successful, the Portuguese turned their attention to the new Brazilian captaincies of Pernambuco and Bahia de Todos os Santos (Bay of All Saints) in the mid 1500s, quickly transforming them into massive sugar producing areas whose rich massapé soil became the lifeblood of the world’s sugar massapé soil became the lifeblood of the world’s sugar massapégrowing trade.

by EDWARD L. BROUGH LUNA

BANTU

REGION

v 1.1, 13 March 2005

At fi rst, the native Tupis were rounded up to work these plantations, but they either resisted fi ercely, fl ed to the interior, or succumbed to European diseases for which they had no resistance. Jesuit missionaries also came into “protect” the natives, who they believed were in desperate need of salvation. As a result, the Portuguese began to depend more on African slaves. Despite being “heathens,” many Africans were familiar with various agricultural practices, and had already proven their endurance under the diffi cult conditions of sugarcane production. Africans also engaged in a complex form of bonded servitude that was deeply embedded into the fabric of African life. Under this diverse system, slaves were usually guaranteed certain rights and privileges as human beings. However, by the late 1500s, as the demand for sugar began to grow exponentially, the Portuguese, along with other opportunistic Europeans and Africans, began to transform this institution into a gruesome, wholesale traffi c of human beings. Over the course of four centuries, as many as 5 million Africans were transported to Brazil—some 40% of all the Africans taken to the Americas (in contrast, North America received only about 5%).4

AFRICANS IN BRAZIL

Under the harsh conditions of capture in Africa (where slaves were usually branded with the mark of the slave raider who captured them), on the horridly overcrowded slave ships (nicknamed tumbeiros, tumbeiros, tumbeiros or “tomb ships”), or under the subsequent “seasoning” process in Brazil, up to half of these people lost their lives. On the putrid slave ships, many Africans believed they had been captured for use as food by the Europeans, so they often attempted to throw themselves overboard. Untold numbers also died from malnutrition, and diseases such as smallpox and dysentery. Those who survived the middle passage usually found themselves at the dismal slave trading centers along the Brazilian coastline: from Maranão in the north, down to Pernambuco, Salvador (Bahia), and Rio de Janeiro in the south. Here, slaves were cleaned up, processed, displayed, and sold like cattle. What little comfort newly arrived Africans may have found in the similarity between the climate and terrain of Brazil and their African homelands5 was quickly tempered by the inescapable and hostile reality of slave life. inescapable and hostile reality of slave life. inescapable and hostile realityIn Brazil, a slave’s useful work life averaged just seven years, so there was little reason for slave owners to provide much in the way of shelter, clothing, proper food, or health care. Unlike the United States, where slaves were considered valuable property, slaves were a replaceable commodity in Brazil.

Yet these “Africans” were not just an undifferentiated mass of people. Each peça (or “piece,” peça (or “piece,” peçaas the Portuguese called their human cargo) was torn from an ethnic/tribal group that had its own history, language, customs, religious beliefs, games, and methods for making war. The African presence in Brazil has thus been greatly infl uenced by the historical cycles of the slave trade, which spanned over 300 years (c. 1520–1850). Portuguese traders often took advantage of a certain tribe’s affi nity for agriculture, or another group’s sophistication in metallurgy, for example. Slaves were thus employed in a wide variety of occupations in Brazil, as agricultural laborers (on sugar, coffee, cotton, and manioc plantations), domestic servants, artisans, barbers, miners, and even bounty hunters (capitães de mato, or “bush captains”) charged with hunting down runaway slaves.

In the hunt for slaves in Africa, early slave traders concentrated on the peoples of the extreme West African coast (Upper Guinea), who had proven themselves to be civilized and adaptable to various work situations. In the 1600s, the need for sheer numbers of slaves to work the sugarcane engenhos led the Portuguese to the populous region of West Central Africa, known engenhos led the Portuguese to the populous region of West Central Africa, known engenhosas Kongo and Angola, where the Portuguese took advantage of instability in the legendary kingdom of the Kongo to capture thousands. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries (and even into the 19th), the Angolan ports of Luanda and Benguela were the primary ports of exit for slaves taken from this vast region. These Bantu-speaking peoples (primarily pastoralists, semi-nomadic cattle herders, and farmers ranging from as far north as the Congo, to as far east as Mozambique) became the most important African infl uence in Brazil.

As slave raiding routes began to encroach upon more isolated territories of the Angolan highlands, including those where dance-fi ghting was practiced, they probably encountered warriors of the engolo and other fi ghting forms. The Portuguese must have also recognized engolo and other fi ghting forms. The Portuguese must have also recognized engolothe prowess of such warrior groups such as the Jaga, who had affi liated with the extraordinary Queen Nzinga (1582–1663) to resist Portuguese advances into Angola in a 40 year guerrilla war. Slave raiders also had to contend with a new political entity in Angola, the imbangala,

Slave quarters(detail from Rugendas, Brazil, c. 1830s)

Working on the sugar mill(Hercules Florence, Brazil, c. 1830s)

which were radical militarized communities in a constant state of readiness (later inspiring the runaway slave communities of Brazil, known as mocambos or mocambos or mocambos quilombos). quilombos). quilombos By 1770, even as the Angolan trade continued unabated, a lastAngolan trade continued unabated, a lastAngolan trade continued unabated, a cycle of slaves were drawn from the Bight of Benin (or present-day Nigeria and Benin). The well educated Yoruba (known in Brazil as the Nâgo) brought their own language, martial arts (such as stick-fi ghting and wrestling), and a complex religion of orixá worship to Brazil, widely orixá worship to Brazil, widely orixá known by the 1800s as umbanda or umbanda or umbanda candomblé.candomblé.candomblé 7

AFRICAN CONTINUITIES

The constant need for new laborers throughout from the 16th to the 19th centuries ensured a steady stream of Africans headed to Brazil. As new arrivals (called boçais) brought their own boçais) brought their own boçaiscustoms and beliefs with them, these often mingled with those already present in (or adapted to) the Brazilian context. Large numbers of displaced Africans thus managed to maintain certain aspects of their own traditions in spite of the sad conditions of slavery, and the dominance of Portuguese language, political institutions, and Roman Catholicism. African customs were also infl uenced by Amerindian culture, especially in the use of local medicinal plants.

While this resulted in the creolization and evolution of many African traditions, many of these—expressed in food, dress, religious practices, movement, words, and attitudes —have not lost their African character, even to the present day. A few (including, arguably, dance-fi ghting) A few (including, arguably, dance-fi ghting) Ahave even been passed on with little alteration.6 This was made possible by the vibrancy of African oral culture, and by the tendency of Africans to organize or identify themselves by ethnic groups. In Brazil, prominent nations (or nações) such as Angola (Bantu), Nâgo (Yoruba), nações) such as Angola (Bantu), Nâgo (Yoruba), naçõesGege, Ijexá, and Malê (Islamicized Africans), as well as other organizations such as work groups (cantos), lay fraternities (cantos), lay fraternities (cantos irmanidades), and a number of secret African societies worked to irmanidades), and a number of secret African societies worked to irmanidadespreserve African traditions (possibly including the engolo), and to engolo), and to engolo help their fellow Africans in matters of spirituality, health, and the assertion of legal rights (such as holding slaveowners accountable for poor treatment, and the right of slaves to buy back their own freedom)accountable for poor treatment, and the right of slaves to buy back their own freedom)accountable for poor treatment, and the right of slaves to buy .

PROBLEMS AND PARALLELS

Unfortunately, it is still not known exactly when or how the practice of African dance-fi ghting arrived in Brazil, or how it may have developed under the conditions of slavery. Research into this important question is complicated by the fact that, throughout the 400-year span of the African slave trade, details about African culture (and its games/dances/fi ghting forms) were often poorly documented, and when they were, they were almost always from a Eurocentric viewpoint. It is also worth remembering that throughout those many years, African cultures continued to change dynamically, either for their own internal reasons, or in response to the slave trade. So we cannot simply speak of a “static” Africa that remained unchanged for over three centuries. Because of this complex picture, and the scarcity of cultural accounts on Brazilian slavery, it may be impossible to determine how a practice like the engolo became engolo became engoloknown as capoeira, or if a single moment marks the “beginning” of capoeira in Brazil.

The existence of other dance-fi ghting forms throughout the Americas offer an intriguing parallel area of research that has just begun to be examined. The ladja or ladja or ladja danmyé of Martinique, the danmyé of Martinique, the danmyébroma of Venezuela, the broma of Venezuela, the broma maní of Cuba, and the secretive “knocking and kicking” of the Southern maní of Cuba, and the secretive “knocking and kicking” of the Southern maníUnited States (all areas of heavy Bantu concentration) seem to share capoeira’s emphasis on leg techniques and the use of headbutts.7 Perhaps African dance-fi ghting was spread from place to place by freed blacks who traveled widely as merchants and mariners throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Or, perhaps it arose in different places out of similar conditions or where various Bantu forms were “creolized.” It has even been suggested that dance-fi ghtingwas developed in Brazil and introduced back to Africa itself, further complicating any attempt to differentiate older traditions from newer practices. In either case, it is clear that what is left of the tradition in Africa itself sadly appears to be dying out, as Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo have been ravaged by years of warfare and mass migration.

RESISTANCE

If current research sees the emergence of capoeira as a kind of “reframing” of African dance-fi ghting traditions under the repressive conditions of slavery in Brazil, there is ample evidence of other forms that evolved in a similar manner. The batuque,batuque,batuque a generic name for a variety of competitive Kongolese/Angolan circle dances transplanted to Brazil, was performed in the plantation slave barracks (or senzalas) during rest days or celebration, with long sessions senzalas) during rest days or celebration, with long sessions senzalasof all-night drumming, chanting, and dancing. These types of dances later gave rise to

Portrait of Salvador(detail from Rugendas, c. 1820s)

the famous samba. Many slave owners, eager to ensure the loyalty of their subjects, often permitted these mysterious and “pagan” expressions of African culture to take place. Dance-fi ghting practitioners may have taken advantage of this, hiding their foot-fi ghting arts as mere amusements embedded in the competitive atmosphere of the batuque. In this context, dance-batuque. In this context, dance-batuquefi ghting was likely used as a mock style of combat that could allow slaves to resolve inter-tribal confl icts through a seemingly innocent “game.” This “game” also commented ironically on the master/slave relationship by temporarily inverting the established order (through the use of upside down movements that mocked the upright Europeans, and possibly symbolized a connection to the underworld), while allowing Africans to reassert their humanity in ways that capoeira continues to serve Afro-Brazilians (and indeed, all capoeira students) today.

Refl ecting this image of slaves performing their dances on the senzalas,senzalas,senzalas capoeira is often described in the oral history as a “fi ght hidden as a dance.” Unable to practice their “martial art” openly, they hid the violent movements of capoeira as a dance, performed right under the noses of the slave owners. This kind of “passive resistance” was common among slaves, who might react to a slaveowner’s poor treatment by organizing work slowdowns or deliberately breaking equipment. Individual slaves could also resist by taking orders too literally, manipulating cultural or linguistic differences, or even drinking heavily to impair the quality of their work. In addition to the usual forms of punishment (whippings, beatings, confi nement in chains, loss of privileges) rebellious slaves were sometimes put against each other in public prize fi ghts, in which it seems likely that capoeira may have been used.

Slaves also reacted to the misery of plantation life by running away and forming their own temporary communities. Enclaves known as mocambos or mocambos or mocambos quilombos (which were modeled after quilombos (which were modeled after quilombosthe Angolan military communities, also called kilombos)kilombos)kilombos were usually parasitic “shantytowns” or dugouts on the fringes of populated areas. On one famous occasion, however, a cluster of these grew to contain as much as one sixth of the population of Brazil. From about 1620 until its destruction in 1695, the Quilombo dos Palmares (located south of Recife) plagued the Portuguese and Dutch, surviving a number of raids and growing to an enormous size, populated by Africans, natives, creoles, and even some Europeans. Its last leader, Zumbi, was betrayed and killed, but even today Zumbi and Palmares are celebrated for their important role as symbols of African resistance to Portuguese domination. Zumbi is also portrayed as having been a capoeira practitioner, but it is not known if or how dance-fi ghting was used for military training, or whether it was merely one of many strategies available to rebel communities. Nor is it known whether capoeira was used in the dozens of slave rebellions that occurred throughout the slavery period in Brazil, including a number of famous revolts in early 1800s Bahia.

ETYMOLOGY OF “CAPOEIRA”

The origins of the very word capoeira are likewise diffi cult to determine. The most popular capoeira are likewise diffi cult to determine. The most popular capoeirasuggestion derives it from caâ-puera, a native Amerindian Tupi word that refers to a burnt scrubland where escaped slaves often took refuge. Another possibility is the Portuguese capoeira, meaning chicken cage or coop, connecting dance-fi ghting with cockfi ghting. A more recent suggestion is the African Kikongo word kipura (among other Bantu derivatives) which kipura (among other Bantu derivatives) which kipurais likewise associated with the fl uttering movements of roosters. Of the three main linguistic infl uences on Brazilian Portuguese (native, Portuguese, and African), however, the African contribution has—like capoeira and its origins in practices like the engolo—been almost engolo—been almost engolocompletely neglected until recently. Further research is therefore likely to enrich this etymology with further African possibilities.

THE URBAN CONTEXT

Whatever the nature of the arrival and development of Angolan/Kongolese foot-fi ghting Whatever the nature of the arrival and development of Angolan/Kongolese foot-fi ghting Wtraditions, the fi rst written citations of capoeira occur in the police records and tourist accounts of Brazil’s main coastal cities of Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, and Recife in the early 1800s. On the narrow streets of these heavily urbanized areas, where newly arrived Africans, acculturated Afro-Brazilian mulattoes, and poor European immigrants mingled, authorities recorded the arrests of hundreds of capoeiras—capoeira players—who engaged in the bloody “war dance” known capoeiras—capoeira players—who engaged in the bloody “war dance” known capoeirasas capoeiragem, or the practice of capoeira. Later, especially in Rio, these streetwise rogues (or malandros) organized themselves into vicious gangs (or malandros) organized themselves into vicious gangs (or malandros maltas) that alternately terrorized and maltas) that alternately terrorized and maltasprotected communities and politicians. In addition to this violent and “spontaneous” street fi ghting form, a more secretive tradition of African dance-fi ghting may have also preserved (as implied by the secrecy surrounding its 19th and 20th century descendant, capoeira angola).capoeira angola).capoeira angola

Jogo de capoeira, ou dance de la guerrecapoeira, ou dance de la guerre(Rugendas, Rio de Janeiro, c. 1820s)

Zumbi dos Palmares, as depicted in QuilomboQuilombo(Diegues, 1984)

The batuquebatuque(Debret, Brazil, c. 1830s)

Many capoeiras also worked seasonally as fi shermen, stevedores, and sailors—occupations capoeiras also worked seasonally as fi shermen, stevedores, and sailors—occupations capoeiraswith many hours of downtime, during which capoeira also came to be known by the ironic euphemism of vadiação (or “doing nothing in particular”).vadiação (or “doing nothing in particular”).vadiação

Given this diverse picture, and the increased internal trading of slaves to other parts of Brazil in the second half of the 19th century, it would appear that a practice once performed in Africa by a relatively small number of people became widely dispersed throughout Brazil under a wide range of circumstances (urban and rural) by Africans, freed blacks (negros de ganho), mulattoes, negros de ganho), mulattoes, negros de ganhocreoles, and a smaller number of European immigrants.

REPRESSION

In the earlier days of Brazilian slavery, as has already been noted, black people were often allowed to practice many of their own traditions, as long as they appeared to work hard and paid their superfi cial devotions to Catholicism. However, by the early 1800s, the number of slave rebellions, as well as a growing—and very racist—perception of African culture as being “primitive” or “degraded,” led to a harsh persecution of all things African. Capoeira, along with the secretive religion of candomblé (to which capoeira is intricately linked), was singled out as a particular threat to the peace, and was punishable by public whipping. When a number of local statutes failed to wipe out the form, the new Republic of Brazil outlawed capoeiragemnationwide in 1890, only two years after the abolition of slavery (the last country in the Western Hemisphere to do so).

Despite its harsh repression, capoeira maintained an uneasy relationship with the state throughout period or repression and national prohibition (c.1820–c.1930). Sometimes, to avoid punishment, practitioners were drafted to serve in the military as soldiers or laborers. During the war with Paraguay in the 1860s, for example, a number of capoeiras (many from capoeiras (many from capoeirasBahia) distinguished themselves by their effectiveness as front-line warriors. At other times, the capoeiras were informally enlisted to help put down domestic disturbances. In popular culture, capoeiras were informally enlisted to help put down domestic disturbances. In popular culture, capoeirasa whole literature romanticizing the dangerous lifestyle of the well-dressed malandro fi gure also malandro fi gure also malandroarose, even as the real-life counterparts of these fi ctional “scoundrels” were being punished and imprisoned for practicing their art.

By the early 1900s, the authorities nearly succeeded in eliminating capoeira altogether. In Rio, where capoeira had been heavily infl uenced by the new underclass of poor Europeans (including the notorious Portuguese knife-wielding fadistas),fadistas),fadistas 8 capoeira had also degenerated into all-out gang warfare (armed with machetes, razors, and clubs). Such violence gave the authorities an excuse to wipe out the maltas without mercy, and as a result, Rio’s maltas without mercy, and as a result, Rio’s maltas capoeira carioca was all but capoeira carioca was all but capoeira cariocalost. It only survived as a cutthroat fi ghting form in a few seedy favelas (“slums”), and as a favelas (“slums”), and as a favelascombative form taught in a few military academies with no ritual or music.9 Meanwhile, in the far northern city of Recife, tough capoeiras were known as capoeiras were known as capoeiras moleques de banda (“band brats”) moleques de banda (“band brats”) moleques de bandawho performed, sometimes with colorful umbrellas, as part of battling street processions. After the police began to repress these displays, some capoeira-like movements were reconfi gured into a dance known as the frevo. It was only in the old colonial capital of Salvador, Bahia (and the surrounding recôncavo of the Bay of All Saints), that capoeira recôncavo of the Bay of All Saints), that capoeira recôncavo managed to survive as a streetwise game-dance-fi ght symbolizing the subterfuge and resistance necessary for everyday survival. Taking on the more deliberate appearance of a dance through the use of drums, tambourines, and an ancient Bantu bow instrument called the berimbau, Bahian capoeira wasalso perhaps the closest living representation of the African dance-fi ght tradition.

TWO MASTERS

Throughout the nationwide period of prohibition, many informal, streetwise mestres (masters) mestres (masters) mestresof capoeira remained active in Bahia. Among these were two remarkable men who fought for the recognition of the form. Both were said to have been taught the tradition by Africans, and it is largely because of their efforts that the secret movements and mythologies of capoeira were fi nally revealed to the world.

Mestre Bimba (c. 1899–1974), originally a much-feared mestre of traditional capoeira, mestre of traditional capoeira, mestredecided to “clean up” what he saw as a “folkloric” and ineffective fi ghting form. By the early 30s, he had created his own, stripped-down version of capoeira, initially called luta regional baiana (or “regional fi ght of Bahia”) to avoid the illegal word, baiana (or “regional fi ght of Bahia”) to avoid the illegal word, baiana capoeira. Under the guidance and infl uence of several of his students (including the doctor and jujitsu enthusiast Cisnando jujitsu enthusiast Cisnando jujitsu

Mestre Bimba - showing his Mestre Bimba - showing his Mestre Bimba meia lua de frente(c. 1950s)

Salvador, Bahia - the former Brazilian capital(c. 1850s)

Taking lashes on the pelourinho, or whipping post(Debret, Brazil, c. 1820s)

Lima), he eliminated many of the ritual functions of capoeira, brought the practice indoors, and introduced a number of pedagogical innovations. These included formalized sequences of movements, uniforms, and specifi c “rites of passage” for his students (such as baptisms and graduations). In short, Bimba “modernized” capoeira. Thanks to his efforts, which included performances for government offi cials of the Getúlio Vargas dictatorship, Bimba’s capoeira (later known only as regional) came to be seen as a legitimate, and uniquely Brazilian cultural regional) came to be seen as a legitimate, and uniquely Brazilian cultural regionalform worthy of preservation. Regional was also well suited for the nationalistic propaganda of Regional was also well suited for the nationalistic propaganda of RegionalVargas’ New State (Estado Novo)Estado Novo)Estado Novo , which proposed the rosy but fi ctitious notion of a raceless, egalitarian Brazil made up of equal parts European, Indian, and African cultures. Under Bimba, capoeira regional also became Brazil’s second “national sport” (after football soccer), appealing capoeira regional also became Brazil’s second “national sport” (after football soccer), appealing capoeira regionalto lighter-skinned and middle class Brazilians, and proving itself to be a devastating fi ghting form that could equal (and often defeat) other martial arts in challenge matches. It was also Bimba’s regional that was eventually seen and spread all throughout Brazil.regional that was eventually seen and spread all throughout Brazil.regional

In the meantime, the traditional capoeira of all other mestres continued as an informal, street-mestres continued as an informal, street-mestressmart, and playful form deeply connected to Afro-Brazilian culture. To distinguish it from the growing style of regional, as well as to acknowledge its Bantu origins in practices such as the regional, as well as to acknowledge its Bantu origins in practices such as the regionalengolo, it became better known as capoeira angola. Among its many mestres—such as Daniel mestres—such as Daniel mestresNoronha, Maré, Waldemar, Cobrinha Verde, João de Bodeiro, and Canjiquinha—the gentle and philosophical Mestre Pastinha (1889–1981) was the best known. His academy, established in the 1940s as the Centro Esportiva de Capoeira Angola (CECA), was an important focal point for capoeira angola, and Bahian culture in general (world-renowned author Jorge Amado was a frequent visitor). It is largely thanks to the elder Pastinha, and the angoleiros who passed angoleiros who passed angoleirosthrough his doors, that many of the traditions of capoeira angola were preserved and passed capoeira angola were preserved and passed capoeira angolaon. Another angoleiro worth noting here was Mestre Waldemar (1916–1990), angoleiro worth noting here was Mestre Waldemar (1916–1990), angoleiro whose outdoor pavilion in the neighborhood of Liberdade hosted many legendary capoeira rodas (“circles”), rodas (“circles”), rodasand who provided the world with its fi rst painted berimbaus.

THE CONTEMPORARY SCENE

In Rio de Janeiro in the 1960s, a group of young capoeira enthusiasts (many of them originally from Bahia) formed the Grupo Senzala, creating a highly stylized version of Mestre Bimba’s luta regional that was inspired by Rio’s own underground tradition of capoeira, as well as other luta regional that was inspired by Rio’s own underground tradition of capoeira, as well as other luta regionalmartial arts and gymnastic practices. Apart from the infl uence of some of Mestre Bimba’s most respected graduates in Bahia, such as Mestres Acordeon, Itapoan, and Dr. Angelo Decânio, the so-called “Senzala style” (and its offshoots, such as Abadá-Capoeira and Omulu), has remained the primary force in the modernization, globalization, and homogenization of capoeira.10

This “contemporary” style, which introduced belt ranking systems and military-style training methods (echoing the move of Rio’s capoeira from the streets to military academies), is also the most public “face” of capoeira: as seen in Hollywood fi lms (such as Only the Strong and Only the Strong and Only the Strong Ocean’s Twelve), commercials, dance performances (such as Jelon Vieira’s famous DanceBrazil), and Twelve), commercials, dance performances (such as Jelon Vieira’s famous DanceBrazil), and Twelvevideo game characters (such as Tekken’s “Eddy Gordo”). Some argue that its extreme popularity and stylization—emphasizing fast games, fi ghting techniques, standardized movements, and powerful, airborne acrobatics—has also sacrifi ced the deeper Afro-Bahian roots of capoeira, where, by contrast, capoeira is still understood as a playful, ritualistic, and somewhat secretive pastime that is highly personal and idiosyncratic.

Indeed, thanks to the rise of the Grupo Senzala’s competitive style of “demonstration” capoeira, the older and more “folkloric” style of capoeira angola was nearly lost. Pastinha’s academy was capoeira angola was nearly lost. Pastinha’s academy was capoeira angolaclosed in the early 1970s due to some governmental double-dealing, but the informal teaching methods of many of the old mestres themselves—who taught only a handful of students at mestres themselves—who taught only a handful of students at mestresa time, without structured lessons—were also partially to blame. By the early 1980s, angolawas slowly revived by Pastinha’s students; fi rst, by Mestre João Pequeno, and later, Mestres João Grande, Boca Rica, Bola Sete, and Curió. Mestre Moraes, a follower of the two Joãos, established the Grupo Capoeira Angola Pelourinho (GCAP) in 1980, teaching a more stylized and politicized form of capoeira angola that has become a meeting point for black consciousness capoeira angola that has become a meeting point for black consciousness capoeira angolaand activism. At the same time, other mestres (including Bahia’s Mestre Neco, Mestre Lua de mestres (including Bahia’s Mestre Neco, Mestre Lua de mestresBobó, and the author’s own Mestre Caboquinho) have followed or revived other lineages of capoeira angola that can trace their heritage back to Bahia’s old street capoeira angola that can trace their heritage back to Bahia’s old street capoeira angola rodas, and far beyond. rodas, and far beyond. rodasIronically, even Mestre Bimba’s “modern” luta regional baiana has also been resuscitated by his luta regional baiana has also been resuscitated by his luta regional baianason Nenél, who is among the very few to strictly adhere to its original teachings.

Postcard showing capoeira regionalcapoeira regional(Salvador, Bahia)

Mestre Moraes’ Grupo Capoeira Angola Pelourinho(Forte do Santo Antônio, Bahia, Brazil)

Traíra and Najé, playing the money game(Barracão do Mestre Waldemar, Barracão do Mestre Waldemar, Barracão do Mestre Waldemar Bahia, 1954)

Mestre Pastinha - waiting for the next moveMestre Pastinha - waiting for the next moveMestre Pastinha(c. 1950s)

CAPOEIRA: A CONTESTED ART

As this article has already made clear, capoeira has been adapted to local conditions throughout As this article has already made clear, capoeira has been adapted to local conditions throughout As this article has already made clearits history: from its origins in African challenge dances, to the senzala slave quarters, the senzala slave quarters, the senzalatransitory quilombo communities, the rough quilombo communities, the rough quilombo favelas of Rio, the colorful parades of Recife, favelas of Rio, the colorful parades of Recife, favelasthe cobblestone ladeiras of Salvador, and now a worldwide network of capoeira academies.ladeiras of Salvador, and now a worldwide network of capoeira academies.ladeirasThe main distinctions between today’s capoeira are between the more-or-less traditionalist angola, the historical luta regional (practiced by very few) and the “contemporary” hybrid of regional (which has often tried to reintegrate movements from regional (which has often tried to reintegrate movements from regional angola). angola). angola Other examples—all heavily infl uenced by “contemporary” capoeira—includeheavily infl uenced by “contemporary” capoeira—includeheavily infl uenced by “contemporary” capoeira choreographed “show” capoeira, tournament-style “sport” capoeira, and the informal capoeira played on the beaches and streets (capoeira da rua). capoeira da rua). capoeira da rua A few individuals have even created their own “brand” of capoeira (such as Mestre Suassuna’s capoeira miudinha, or “small capoeira”).

All these styles of Brazilian capoeira (not to mention the cognates found elsewhere in the Americas) may indeed represent different manifestations, “reframings,” or “revivals” of African dance-fi ghting traditions. However, because of this, capoeira is often framed to suit a particular point of view: groups that emphasize the fi ghting aspect of capoeira may point to the effectiveness of Rio’s maltas or Bimba’s prize-fi ghting daysmaltas or Bimba’s prize-fi ghting daysmaltas ; Brazilian nationalists may insist on the form’s origin in multicultural Brazil; Afro-centrists may emphasize its “pure” African roots; those who create their own style may seek justifi cation in the example of Bimba’s luta regional, and so on.regional, and so on.regional To be sTo be sT ure, many traditions of capoeira have been lost, rediscovered, and reinvented throughout the years, especially in the 20th century. Even since the 1960s, the Grupo Senzala’s aggressive stylization of regional, and later, the bringing of regional, and later, the bringing of regional angola under the angola under the angolaroof of the academy, have irrevocably changed the practice and appearance of capoeira. Given all these changes, some have wondered if it is possible, or even relevant, to claim an “authentic” style or tradition of capoeira.

Many of the practitioners of the “contemporary” style of capoeira therefore justify the “modern” and “innovative” aspects of capoeira, and promote capoeira as a powerful “sport” worthy of Olympic contention. Traditional capoeira, meanwhile, is seen as a valuable, but rather “quaint” and “folkloric” form that has seen better days. Often, in the genuine belief that the traditional and the modern ought to be brought together into a single, unifi ed practice of capoeira (“a capoeira é uma só,” or “capoeira is only one”), contemporary practitioners train in both styles, one played “low and slow,” the other “fast and furious,” in order to master a “complete” art.

However, these tendencies—which dominate the worldwide practice of capoeira—are based on arrogant assumptions that are strongly refuted by traditionalists. Angoleiros point to agenuine continuity of tradition that can be traced directly to late 1800s Bahia, and indirectly hundreds of years earlier, to the experiences of Africans under slavery and the challenge dances of Africa itself. While few would argue that some of its superfi cial aspects have evolved and/or changed (such as the standardization of its teaching methods), angoleiros nonetheless believe angoleiros nonetheless believe angoleirosthat their tradition represents a core of philosophical and bodily practices that havew survived for hundreds of years relatively intact. Meanwhile, the Senzala style is just a fl ashy 1960s reinterpretation of Bimba’s regional, which itself broke completely from the capoeira of its day. regional, which itself broke completely from the capoeira of its day. regionalAs such, it has little connection to its own traditions, and even less connection to the precious, living traditions of capoeira angola, of which it has only a superfi cial understanding

The passage of secrets in candomblé offers another way to understand this issue. In the candomblé offers another way to understand this issue. In the candomblé orixátradition—stronger in Bahia than in Africa itself—there are candomblé houses that are candomblé houses that are candombléwelcoming to tourists and journalists, but there are many houses that are closed off to outsiders. Likewise, capoeira has its “visible” aspects, as well as “secret” aspects which are only accessible to the holders of tradition. The awe-inspiring movements and exaggerated games so often seen in the “contemporary” style may therefore be properly understood as merely the most “visible” aspect of a practice that continues to maintain many secrets and contradictions.

THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN CAPOEIRA

Although a few women are mentioned in lists of old capoeira mestres (including Palmeirona, mestres (including Palmeirona, mestresMaria Cachoeira, and Maria Pé no Mato11), little is known about the historical role of women in this traditionally male art. The participation of women may have simply been constrained by the clearer distinction between gender roles in Brazilian society, or by issues of fashion (as it is diffi cult to properly execute capoeira movements in the fl owing white dresses of the baianas). baianas). baianas

Staging the ginga at Mestre Acordeon’s academyStaging the ginga at Mestre Acordeon’s academy(Berkeley, CA, c, 1999)

“Eddy Gordo” from Tekken 3 fi ghting game(Namco, 1996)

DanceBrazil(Lois Greenfi eld, 1996)

Candomblé priestress priestress mblé priestress mbléduring ceremony calling the orixásorixás

On the other hand, women have always dominated the highest positions as priestesses in the religion of candomblé, and most self-respecting Brazilians make offerings to the sea goddess candomblé, and most self-respecting Brazilians make offerings to the sea goddess candombléIemanjá, one of the most powerful orixás in the orixás in the orixás candomblé pantheon.candomblé pantheon.candomblé

Yet even as there remains a stigma against capoeira in Brazilian culture itself, women have recently become more and more involved in the practice (especially outside of Brazil). Several remarkable women have even gained higher titles in both angola and the newer styles. Among angola and the newer styles. Among angolaBahian angoleiras, Mestra Jararaca (graduated by Curió) is the best known, along with her sister angoleiras, Mestra Jararaca (graduated by Curió) is the best known, along with her sister angoleirasProfessora Ritinha (of João Pequeno). In the U.S., angoleiro Mestre Caboquinho has graduated angoleiro Mestre Caboquinho has graduated angoleirotwo contra (or “half ”) contra (or “half ”) contra mestres, named Biriba and Rapidinha. Among representatives of mestres, named Biriba and Rapidinha. Among representatives of mestres regional/regional/regionalcontemporary capoeira, Mestre Acordeon has graduated the fi rst non-Brazilian mestra, Suelly, while Abadá’s famous Mestre Camisa (formerly of Senzala) has graduated the Brazilian-born mestrandas Edna Lima (New York City) and Cigarra (San Francisco).mestrandas Edna Lima (New York City) and Cigarra (San Francisco).mestrandas

CONCLUSION

Regardless of its external appearances (such as gender, race, or “style”), the future practice of capoeira—as a cunning game, a ritualized combat, a show for tourists, or a tournament-style martial art—is now in the hands of Brazilians and non-Brazilians, traditionalists and modernists, women and men alike. At its best, it is hoped that capoeira may remain a deeply ambivalent game that allows its practitioners to “play” through life’s dilemmas and contradictions with a smile on the face. And so, it is with this diversity of voices—contemporary, traditional, competitive, and streetwise—that capoeira is poised to survive for centuries to come.

NOTES

1. The author has been a student of Mestre Caboquinho of Salvador, Bahia, Brazil since 2002.

2. Desch-Obi (2001) is my primary source regarding the engolo and dance-fi ghting, but spelled as engolo and dance-fi ghting, but spelled as engolo n’golo, it has

been cited by Cascudo (1967), Mestre Pastinha, the GCAP organization, and Mestre Caboquinho.

3. This proverb is cited by Dawson (1993) as being relayed to him by noted Kongolese scholar K. Kia Bunseki

Fu-Kiau.

4. Statistics on the African slave trade are notoriously diffi cult to pin down, however Alistair Boddy-Evans’

article (http://africanhistory.about.com/library/weekly/aa080601a.htm) provides reasonable estimates.

5. Robert A. Voeks (1997, p. 8–32) has done a vivid analysis and comparison between the African and

Brazilian coastlines.

6. Pierre Verger has written extensively on the African presence in Brazil, as well as the cycles of the slave trade,

and specifi c African traditions that were brought to Brazil.

7. Of these forms, only ladja has been well documented (Dunham, 1939). Desch-Obi (2001) has discussed ladja has been well documented (Dunham, 1939). Desch-Obi (2001) has discussed ladja

“knocking and kicking” somewhat thoroughly, but it remains very secretive. The others are either extinct,

sketchy, or remain part of folk traditions yet to be researched.

8. On the Portuguese contributions to capoeira in the late 1800s, see Soares (1994).

9. A manual written anonymously by an offi cer at one of these academies was published in Rio in 1906.

10. See Nestor Capoeira (2002, pp. 212–219) for an excellent account of the Grupo Senzala, mostly from

within.

11. These and a few other women are listed in Mestre Bola Sete (1989, p. 27).

MORE SELECTED READING

Browning, Barbara. “Headspin.” Samba: Resistance in Motion. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 1995.

Capoeira Ginga Nâgo. France: <http://www.ginganago.com/>.

Capoeira, Nestor. Capoeira: Roots of the Dance-Fight-Game.Capoeira: Roots of the Dance-Fight-Game.Capoeira: Roots of the Dance-Fight-Game Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2002.

Desch-Obi, Thomas J. “Engolo: Combat Traditions in African and African Diaspora History.” Ph. D. Thesis UCLA,

2000. Ann Arbor: UMI, 2001.

Downey, Greg. “Incorporating Capoeira: Phenomenology of a Movement Discpline.” Doctoral dissertation, U of

Chicago, 1998.

Karasch, Mary C. Slave life in Rio de Janeiro, 1808-1850. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UP, 1987.Slave life in Rio de Janeiro, 1808-1850. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UP, 1987.Slave life in Rio de Janeiro, 1808-1850

Lewis, J. Lowell. Ring of Liberation: Deceptive Discourse in Brazilian Capoeira. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1992.

Rego, Waldeloir. Capoeira Angola: Ensaio Sócio-etnográfi co. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Itapuã, 1968.

Sweet, James H. Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441-1770. Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441-1770. Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Religion in the African-Portuguese World, 1441-1770 Chapel

Hill, NC: U of North Carolina P, 2003.

Thompson, Robert Farris. “Black martial arts of the Caribbean.” Review of Latin Literature and Arts. n37. 1987.

Contra-Mestre Rapidinha of T.A.B.C.A.T.One day before giving birth (2005)