Can the travel planning process be improved? A Kent case study, 2012.

-

Upload

thomas-king -

Category

Travel

-

view

1.558 -

download

0

Transcript of Can the travel planning process be improved? A Kent case study, 2012.

University of Westminster

School of Architecture and the Built Environment

Can the travel planning process be improved? A Kent case study.

MSc Transport Planning & Management - 2012

Thomas King

2

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all those that have assisted me in the production of this study and throughout the duration of the course. In particular I would like to thank the following:

Peter White and Peter Stanley who have supported me during the year in the development of my study. Many thanks for your advice.

My employer, Kent County Council who have provided the financial assistance to permit me to complete this course, and to my colleagues Katie Pettitt and Charlotte Owen who assisted with the development and collection of the study data as part of a wider paper on ‘Making Workplace Travel Plans Work’.

My family and friends who have supported me throughout the two year course.

Lastly I would like to thank those who assisted me in the data collection stage of this study by agreeing to be interviewed.

3

Abstract

Despite popularisation of the terms over 20 years ago Agenda21 and sustainability are still current, topical issues, which attract attention and stimulate debate at the highest levels of global governance. This study examines the early ideas of sustainability to understand the role it has played within global and UK national policy. One of the key local impacts as a consequence of this global debate has been the creation of Travel Plans as a method to minimise the impact of growing traffic associated with new developments. By examining the rise of global and national policy, this study seeks to understand how Kent County Council, and organisations within the County have developed, implemented and operated their Travel Plans.

Of particular interest is the view that Travel Plans are not producing the outcomes originally intended. As a result, the research undertaken as part of this study is designed to look at site-specific examples to understand the problems associated with trying to implement and run a successful Travel Plan. Importantly this will touch on the wider issues of national policy, local government and the problems faced by businesses trying to achieve tangible results. This study will conclude by highlighting the key areas that need to be tackled at both the national, local and organisational level if Travel Plans are to become successful and more widespread across the UK.

Word count: 19,938

Contents

1. Introduction ............................................................................................. 4

1.1. Aims .................................................................................................... 4

1.2. Structure .............................................................................................. 4

1.3. Conclusion .......................................................................................... 5

2. Literature review ...................................................................................... 6

2.1. Introduction ......................................................................................... 6

2.2. Sustainability “Agenda21” ................................................................... 6

2.3. Theoretical approaches to sustainability ............................................. 8

2.4. National and local policy background .................................................. 9

2.5. Travel Plan background .................................................................... 11

2.6. PPG13 ............................................................................................... 11

2.7. NPPF................................................................................................. 12

2.8. Travel Plan types .............................................................................. 13

2.9. International Travel Plans and fiscal incentives ................................. 14

2.10. Corporate social responsibilities ........................................................ 15

2.11. Conclusion ........................................................................................ 18

3. Methodology .......................................................................................... 20

3.1. Introduction ....................................................................................... 20

3.2. Choice of topic .................................................................................. 20

3.3. Study design ..................................................................................... 20

3.4. Qualitative data ................................................................................. 22

3.5. Quantitative data ............................................................................... 23

3.6. Data analysis ..................................................................................... 24

3.7. Ethical considerations and data protection ........................................ 24

3.8. Conclusion ........................................................................................ 25

2

4. Results & analysis ................................................................................. 26

4.1. Online survey responses ................................................................... 26

4.2. Creation ............................................................................................. 27

4.3. Implementation .................................................................................. 30

4.4. Reviewing .......................................................................................... 31

4.5. Engagement ...................................................................................... 33

4.6. Success ............................................................................................. 34

4.7. In-depth telephone interviews ........................................................... 36

4.8. Response summary .......................................................................... 38

4.9. In-depth telephone interview analysis ............................................... 41

4.10. Kent County Council interviews ......................................................... 42

4.11. Sustainable Transport Manager interview ......................................... 43

4.12. Senior Development Planner interview ............................................. 44

4.13. Conclusion ........................................................................................ 46

5. Conclusion ............................................................................................. 48

5.1. Introduction ....................................................................................... 48

5.2. To explain the origins of Travel Plans ............................................... 48

5.3. To identify past and present policies relating to Travel Plans ............ 49

5.4. To investigate how KCC manages the Travel Plan process.............. 51

5.5. To research how companies are managing their Travel Plans .......... 52

5.6. To identify constraints within the travel planning process ................. 53

5.7. To establish how Travel Plans can be improved ............................... 55

5.8. Limitations ......................................................................................... 58

5.9. Further research ideas ...................................................................... 58

6. References & Bibliography ................................................................... 60

6.1. References ........................................................................................ 60

6.2. Bibliography ...................................................................................... 64

3

Appendix

Appendix A - Online survey results

- Online survey letter

- Online survey responses

- ‘Making Workplace Travel Plans Work’ Paper

Appendix B - In-depth telephone interview transcripts

List of figures

Figure 01 - The research process. Figure 02 - Online survey responsibility responses. Figure 03 - Online survey ‘why’ responses. Figure 04 - Online survey key features responses. Figure 05 - Online survey problems responses. Figure 06 - Online survey implementation problem responses. Figure 07 - Online survey updating responses. Figure 08 - Online survey behavioural changes. Figure 09 - Online survey engagement responses. Figure 10 - Online survey satisfaction responses. Figure 11 - Online survey successful / unsuccessful key points. Figure 12 - Online survey improvement responses. Figure 13 - Online survey improvement responses.

List of tables

Table 01 - Follow-up interview sites. Table 02 - KCC iTRACE database breakdown. Table 03 - Online survey response breakdown. Table 04 - Follow-up interview sites.

4

1. Introduction

This study seeks to explore the issues surrounding Travel Plans and the wider policies that have developed over the past two decades. It will encompass the pressures of global, national and local policies, which have continued to evolve from the very early ideas of Agenda21 and sustainability.

The main focus of the study will be to look at existing Travel Plans required as part of a Section 106 agreement, and where possible, Plans which have been developed on a voluntary basis. In order to deconstruct the current situation in the UK I will be contacting businesses that have introduced Travel Plans, initially to understand how their Plans were developed, but also to identify the possible impacts this has had on changing employee travel behaviour.

Crucial to understanding how Travel Plans could be further enhanced, it is important to determine if the current fluid situation surrounding national and local government Travel Plan policy is impacting upon their long-term viability. If it is, what policy changes are required? and what can one learn and indeed recommend having considered the thoughts and opinions of businesses that have implemented plans in recent years?

1.1. Aims

This study has a number of aims:

1. To explain the origins of Travel Plans; 2. To identify past and present policies relating to Travel Plans; 3. To investigate how KCC manages the Travel Plan process; 4. To research how companies are managing their Travel Plans; 5. To identify constraints within the travel planning process; and 6. To establish how Travel Plans can be improved.

1.2. Structure

In order to achieve these aims, this study will be structured into the following sections:

(a) Literature review - concerned with framing the context of the study from an abstract stage, moving towards a more concrete account of today’s situation. In order to do this, the study will look at the origins of sustainability and the original Agenda21 movement. It will then focus on the national and local government policies that have been developed. It will also cover international examples, along with the move towards fiscally incentivising Travel Plan development.

(b) Methodology - this section is concerned with identifying the study choice and design. It will also identify the use of quantitative and qualitative data and set out how this is going to be analysed to help answer the main aims of this study.

5

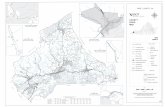

(c) Results - this section will include analysis of research undertaken via contacts obtained by accessing Kent County Council’s iTRACE database of implemented Travel Plans. To enhance the initial research further, additional in-depth interviews will be undertaken with a selection of the initial respondents. As part of understanding how Travel Plan policy is changing at the more local level, interviews will also be carried out with key members of staff at Kent County Council.

(d) Conclusion - to conclude this study and answer the original aims, the conclusion will firstly deal with the responses to the initial survey; secondly the in-depth interview information will be introduced, and finally the results from the interviews undertaken with Kent County Council. This will all be used to try and answer the main aims of the study and to understand what needs to be done to improve the performance and longevity of Travel Plans in the UK.

1.3. Conclusion

By setting this study within the context of current planning policy regime and also including the origins of Travel Plans, it is envisaged it will be possible to set the scene for making suggestions for future improvements to the UK’s travel planning process. By collecting data from live Travel Plans the study will be able to establish what progress has been made, and where improvements could or should be introduced. Today’s society is a dynamic one, with issues of sustainability and new environmental policies continually being adapted and developed by successive governments. This study will also seek to evaluate the current situation by connecting live Travel Plan examples with current Government policies and looking at how they perform. In order for Travel Plans to continue, there is a real need to have a better understanding of what businesses require from future policies. This will enable businesses to introduce Travel Plans that produce meaningful results, as opposed to just being a ‘box-ticking exercise’.

6

2. Literature review

2.1. Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to set the study within a context that will introduce the reader to the notion of Travel Plans, as well as the national and local polices that have guided their development over the past two decades.

The literature review will seek to focus on the rise in importance of the term “sustainability” in the public and political conscience and the ideas of Agenda21. It will then look at the increasing prevalence of Travel Plans and the history surrounding the securing, enforcing and monitoring of such Plans as a result of national policies, such as PPG13. In addition to this, the review will look at the rise in corporate and social responsibility, and the changing attitudes this has brought towards sustainability and Agenda21.

This chapter has been structured in such a way to allow the reader to follow the ‘journey’ of Travel Plans from the theoretical abstract ideas, through to the polices that have led to a change in attitude by many companies towards their social responsibilities. A key question throughout this literature review is whether current policies are successfully influencing and changing travel behaviour to produce more sustainable patterns of commuting for the foreseeable future.

2.2. Sustainability “Agenda21”

Agenda21 is a voluntarily implemented action plan of the United Nations first produced at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (“UNCED”) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1992. The Agenda21 plan fundamentally outlines the understanding that the environment must be integrated into all the policies and actions of industry, Government and consumers, and attempts to address the causes of environmental degradation as a means of creating a more sustainable economy and society. Agenda21 has played an important part in raising the awareness of sustainability as a term and as a global movement towards creating a more ecological balance. Since the early 1990s, issues of Agenda21 have been considered to be one of the world’s most important concepts for beginning to deal with the subject of sustainability. Lele (1991, p.613) remarked that its development is a ‘metafix’ that will unite everybody from the profit minded industrialists and risk minimising subsistence farmers to the equity seeking social workers. These local environmental strategies are not only linked to changing national priorities, but also reflect the particular economic, environmental and political challenges impacting on decision making in each locality (John, White & Gibb, 2004, pp. 151-168). Peck (1998, pp. 5-21) suggests that the issues of Agenda21 offer more means to contribute to democratic renewal in the UK than perhaps any other function of local government.

As it stands, Agenda21 does not have a formal authority of its own to direct others to green their policies; hence it relies on a more ‘bottom-up’ approach to integration. To speed up reform, past and present Governments have

7

looked to capitalise on the ideas of Agenda21. However, as a term, Agenda21 has now been superseded by the term ‘sustainability’ (Wilkinson, 1997, pp. 153-173). This builds on the work of Agenda21, but also starts to draw on new policies and binding regulations as part of the planning process. It also seeks to widen the scope of Agenda21 to cover areas such as: jobs; energy; cities; food; water; oceans; and disasters (RIO+20 UN, 2012).

Given heightened awareness and political pressures, the world’s governments can no longer afford to ignore the environmental agenda (Cocklin and Blundel, 1998, p. 59). With the development of national and international policies, we are starting to see planning policies that set out more detailed parameters for local authorities to follow. Currently, local economic pressures, interests and traditions have led to significant spatial variations in local environmental politics and policies. O’Brien and Penna, (1997, p. 186) believe that some aspects of the economic and political system privilege some strategies over others, this has resulted in certain places and regions benefiting more so than others.

In England there is evidence of a marked variation in the commitment and approaches towards sustainability and Travel Plans. These appear to reflect ‘local contingencies’ and depend upon how local authorities have chosen to manage their interests. Research by Emma Young in 2011 highlights one difference - Travel Plan enforcement. Her study showed that out of 86 Local Authorities, 46 knew of examples where Travel Plans subject to planning conditions or Section 106 agreements had not been implemented, yet very little evidence is available to demonstrate how Local Authorities have been enforcing planning conditions. It is clear from Young’s study and others that different local authorities are prioritising some environmental policies over others, and developing different ways of managing local economic-environmental tensions to satisfy both local and political needs and interests.

An alternative interpretation is that uneven development and rollout of Agenda21 has arisen as a result of the rapidly changing landscape of local and regional governance and state agendas; termed ‘local strategic selectivity’. Without strong governmental prescription of targets and definitions, a wide range of interpretations have developed. Furthermore, competing pressures and resource constraints has meant Agenda21 was unlikely to top the agendas of most local authorities that continue to be preoccupied with increasing economic development (Patternson & Theobald, 1996, p. 10). Consequently, as Agenda21 became incorporated it was simultaneously being detached from the key priorities in local and regional governance. In 2000 the then Labour Government introduced the Local Government Act. This gave greater discretionary power to local authorities to promote economic, social or environmental wellbeing, whilst also requiring community strategies to be prepared.

Bruff and Wood (2000, pp. 519-539) saw this change as a move away from market-based concerns, to one more in touch with the wider conceptions of local services and priorities. It is also a reverse to a traditionally conservative approach to encourage innovation and closer working between local authorities and their partners to improve communities’ quality of life (DETR,

8

2000, p. 7). Pinfield& Saunders (2000, pp.15-18) believe on the other hand that this Act marks a shift to a ‘weaker’ meaning for the term ‘sustainable development’ in comparison with the spirit of local Agenda21.

2.3. Theoretical approaches to sustainability

Sustainable development has been discussed extensively over the past two decades in political, economic and social forums alike; however the meaning of the word is something that remains contested. The geographical scale at which sustainability is viewed is most often global, dealing with the conceptual issues rather than actual policy change. Breheny (1992) believes it is this lack of empirical applicability, which has resulted in the discipline of sustainability becoming so contested. The range of literature on the topic is extensive and encompasses varying fields as detailed earlier in the literature review.

Sustainable development ought to mean the creation of a society and an economy that can come to terms with the life-support limits of the planet. But as Class (1997, p. 2) has discovered, the current approach to sustainable development can only be described as a “chimera, a theoretical position that attracts attention, stimulates debate and raises awareness about the scope and transition to a less unsustainable world”. The main difficulty with sustainable development lies not just in its ambiguity; there is a real issue of democratic probity at stake, if a majority honestly does not want to pay what it sees as ‘the price’ for sustainable development, who is to deny them their legitimate wish? As Shen (1997, p.76) explains “a multifaceted approach is necessary”. Muschett (1997, p.81) explains in his work that “sustainable development occurs when management goals and action are simultaneously ecologically viable, economically feasible and socially desirable; these imply environmental soundness and political acceptability”. The term ‘sustainable development’ has had widespread political usage because of its broad application and vague definition. If we are to tackle these problems, sustainability requires a fundamental shift in value and behaviour (Smith, Whitelegg & Williams 1998). This includes a shift from materialism to a more holistic view of what constitutes quality of life. Intangible, but also real elements of human contentment such as social cohesion, community and self-development must also be given greater priority.

Today sustainable development is a socially motivating force, in O’Riordan & Voisey’s (1997) book Sustainable development in Western Europe the authors perceive that because we globally understand our long-term survival is at stake, we will continue to develop the term ‘sustainability’. This may ultimately prove to be the most important driver towards envisioning a sustainable future. Muschett (1997) believes that in order to break through these barriers, government leadership, private sector ingenuity and public support will be required. Regulatory obstacles will also need to be removed to support this process.

Key to tackling regulatory obstacles is the hierarchical assignment of responsibility, which to a certain extent is still held by a central authority. Kairiukstis (1989) believes that the objectives of sustainable development may be achieved more easily if the process of socioeconomic development

9

and environmental change are implemented on a more regional, or local scale. Going back to Rio in 1992, the importance of local authorities and municipalities was stressed as a way of achieving sustainable development. Beck (1992, pp.37-74) suggests we are slowly moving in the direction of more local frameworks where we will no longer see politicians exclusively carrying out many tasks. As a consequence, numerous social and environmental non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have become important political actors, opening up a whole new area of ‘sub politics’, potentially adding an additional layer of complexity to a system already poorly understood.

2.4. National and local policy background

The implementation of a sustainable approach to planning relies on the creation of strong national and local policies and guidance to support Travel Plans. Bond and Brooks’ (1997, pp. 305-321) work shows that national guidance is often created in a hope to provide impetus for further methodological development at a more local level. In July 1998 the Labour Government released a white paper on transport policy ‘A New Deal for Transport: Better for Everyone’, this was intended to decrease the dependence on the private car, (T. Rye, 2002, p287-298) whilst promoting a policy to encourage the voluntary take up of Travel Plans.

National Government policies are about providing local authorities with the information and guidance necessary to enable them to become proactive. In the case of Travel Plans it is about putting in place the necessary support structures to enable collaborative working between public and private organisations. National policies are ideal for creating a top-down approach for tackling issues such as a national plan for dealing with traffic congestion, or national strategy for reducing CO2 emissions, they do not however provide a solution to deal with the more localised issues, for instance, tackling the very source of the problem hampering the success of Travel Plans; the stereotypical views people hold of the private car. A study by Lek in 1999 found that 61% of 14 - 16 year olds viewed a car as essential to their lives. In order to tackle these views Pacione (2002) believes that national policies need to be implemented and tackled at the local level. It has also been argued by Allen, Anderson & Browne (1997, pp. 3-6) in their study Urban Logistics that Pacione’s idea of implementing change at the local level must also be backed up by more prescribed national plans in order to promote the purpose of greener credentials to the widest possible audience.

In response to national frameworks produced by the Government, local authorities have drawn up localised Regional Spatial Strategies to try and tackle some of these problems. The South East Plan (2009) has a chapter focused on transport, which highlights the importance of transport issues within Kent and the wider south east region. The policy states:

“Monitored travel information for the south east shows an increase in overall travel per person since 2004, including an increase in travel by car […] the need to re-balance the transport system in favour of sustainable modes is recognised throughout this Plan […] our vision is a high quality transport system to act as a catalyst for continued economic growth”

10

As part of the South East Plan, all local authorities are required to ensure their local development documents and transport plans identify any developments that could create additional traffic constraints on the transport network and ensure a Travel Plan is developed. More recently Local Authorities have been creating their Local Development Plans; the bulk of which involves the establishment of the Local Development Framework (“LDF”) Core Strategy. The policies contained within the LDF are then used to outline policies against which all development within an area is assessed. LDF policies take their guidance from national Planning Policy Statements and from policies contained within Regional Plans.

Government policies, both nationally and locally are designed to facilitate change, for example Travel Plans are about changing travel habits and ensuring shorter commuter trips are able to occur by green modes or by public transport, and where this is not possible, to support alternatives such as car sharing schemes (Banister, 1999). However, according to the UK round table on sustainable development (Southwood, 1996, p. 5).

“There is no magic solution to the many problems caused by present land transport patterns and trends”.

For this reason we need to have a greater range of co-ordinated strategies to minimise current and anticipated future adverse impacts. In 1999 the Transport Bill provided the legal framework for a number of measures designed to support travel planning, including the introduction of work place parking charges (Green et al, 2011, pp. 235-243). One of the only Councils to introduce this policy has been Nottingham County Council. Businesses with more than 11 spaces will be charged £288 a year per space, rising to £380 by 2015. The levy has been introduced to pay for transport improvements, including the extension of Nottingham's tram network. Many employers have decided to pass on some or all of the charge to their staff while some have reduced their number of car parking spaces. AA president Edmund King said that schemes such as this will damage the economy and hit employees who just can't afford it (BBC News, 2012). It remains to be seen if this new policy measure has been effective at reducing congestion and creating a modal shift towards public transport.

Presently in the UK the planning process is the only national mandatory route by which a Local Authority can require a Travel Plan to be produced (Roby, 2010). It has long been acknowledged that the current setup is overly burdensome to ensure any commitment and that outcomes are enforced (LTT Issue 575). Similarly, even following the introduction of national policies which allowed devolution of power to local authorities to develop congestion charging zones and workplace parking levies, very little progress has been made on the case for private firms to voluntarily create and implement a Travel Plan. Furthermore, given the nature of modern development, it is often the case that suburban and city-edge sites are being required to produce Travel Plans, as opposed to existing inner-city sites where there is often greater need. Existing national policies make no attempt to tackle this problem (Enoch et al, 2003). Research by Rye and MacLeod in 1998 concluded that employers must believe that there is a transport problem which impacts upon their site and in addition to this, that they have a responsibility, or some

11

responsibility to solve it. As a consequence, any future policy changes are going to need to engender confidence in the national system, whilst locally it is going to be important to develop ownership and accountability if Travel Plans are to be successful.

2.5. Travel Plan background

A great deal of information now exists on what Travel Plans are and how to develop them. However, the effective implementation of such plans has been far from easy to secure (Coleman, 2000, p139-148). A Travel Plan can be described as:

“A package of measures implemented by an organisation to encourage people who travel to/from that organisation to do so by means other than driving alone by private car”.

Presently, Travel Plans are introduced to solve a very local problem, which may be site or area specific and generally relate to congestion or a parking shortage (Bradshaw, 2001). Kent County Council’s guidance on securing, monitoring and enforcing Travel Plans in Kent (2012) defines a Travel Plan as:

“A strategy for managing multi-modal access to a site or development focusing on promoting access by sustainable modes.”

From a point 20 years ago when Travel Plans where unknown in the UK, they have now become a central part of UK policy, especially English transport policy and the wider “Smarter Choices” (2005) agenda. This is mainly down to global influences, such as the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, which spawned a new movement demanding greater accountability for the global environment.

Today, Travel Plans can be implemented voluntarily, though it is more likely that a Travel Plan will be required as part of a new, or expanding development that requires planning permission. It should be remembered that even when a Travel Plan is being provided, it cannot justify the siting of a development in a totally unsuitable location. However, a sufficiently strong Travel Plan may help to counterbalance the disadvantage of a site where sustainable access, without Travel Plan measures would be less than ideal.

2.6. PPG13

Travel Plans were first included within national planning policy in Planning Policy Guidance Note 13 (“PPG13”) in March 2001. PPG13 stated that:

“The Government wants to help raise awareness of the impacts of travel decisions and promote the widespread use of Travel Plans amongst businesses, schools, hospitals, and other organisations. Local Authorities are expected to consider setting local targets for the adoption of Travel Plans by local business and other organisations and to set an example by adopting their own plans.”

12

PPG13 did not set out any standard format, or content for Travel Plans. It did however state that their relevance to planning lies in the delivery of sustainable transport objectives, including:

Reduction in car usage and increased use of public transport, walking and cycling;

Reduce traffic speeds and improved road safety and personal security particularly for pedestrians and cyclists; and

More environmentally friendly delivery and freight movements, including home delivery services.

PPG13 was also supported by a number of other guidance documents including:

Making residential Travel Plans work: guidelines for new development -DfT, 2007;

The Essential Guide to Travel Planning - DfT, 2008; and

Good Practice Guidelines: Delivering Travel Plans through the planning system - DfT, 2009.

2.7. NPPF

In 2012 PPG13 was superseded by The National Planning Policy Framework (“NPPF”), this combined existing guidance into one easily accessible document. The emphasis on sustainable transport has remained consistent, and NPPF continues to place an importance on the use of Travel Plans. It recommends that Travel Plans should be submitted alongside all planning applications that are likely to have a significant transport implication (Communities & Local Government, 2011, point 89). In the locating and designing of developments, NPPF states the need to:

Efficiently deliver goods and supplies;

Priorities pedestrian and cycle movements;

Have access to high quality public transport facilities;

Create safe and secure layouts;

Minimise conflict between traffic and cyclists or pedestrians;

Avoid street clutter;

Where appropriate establish home zones;

Incorporate facilities for charging plug-in and other ultra-low vehicles; and

Consider the needs of people with disabilities by all modes of transport.

13

NPPF goes on to emphasise that the primary purpose of the planning system is to contribute to the achievement of sustainable development, which it defines as:

"Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987).

Sustainable development is central to the economic, environmental and social success of the country and is the core principle underpinning planning. For the planning system, delivering sustainable development means:

Planning for prosperity (an economic role) use the planning system to build a strong, responsive and competitive economy, by ensuring that sufficient land of the right type, and in the right place, is available to allow growth and innovation; and by identifying and coordinating development requirements, including the provision of infrastructure;

Planning for people (a social role) use the planning system to promote strong, vibrant and healthy communities, by providing an increased supply of housing to meet the needs of present and future generations; and by creating a good quality built environment, with accessible local services that reflect the community’s needs and support its health and well-being; and

Planning for places (an environmental role) – use the planning system to protect and enhance our natural, built and historic environment, to use natural resources prudently and to mitigate and adapt to climate change, including moving to a low-carbon economy.

2.8. Travel Plan types

The framework recommends that three components; economic, social and environmental, should be considered in an integrated way, looking for solutions that deliver the best-combined approach. It is envisaged that the planning system must play a much more active role in guiding development towards a sustainable solution. A key requirement to facilitate this will be delivered through a Travel Plan. It is recommended that all developments generating significant amounts of movement should be required to produce a Travel Plan. This is however only possible if Travel Plans are embedded within Local Planning Policy, including Local Development Frameworks.

Travel Plans have three distinct process stages, somewhat different to the historically drawn out process, which led to confusion and failure of past Travel Plans under PPG13:

1. Framework Travel Plans. These are normally secured at Outline Planning Stage, and may be submitted or secured as part of a Full/ Detailed Planning Application, provided there is a clear and agreed pathway for submission of a Detail Travel Plan.

14

2. Detailed Travel Plan. These should be submitted with a Full/Detail Planning Application. In some cases it may be deemed appropriate that the Developer or Site Management Company oversees the Plan. Alternatively, the requirement may be devolved to individual tenants, however where this occurs, the Developer or Site Management Company who submitted the Travel Plan retains overall accountability, with tenants requirements secured through the Tenancy Agreement.

3. Small Business Pro-forma Travel Plan. These are normally for multi-use sites with a number of small business units. It may be unnecessarily onerous to require the development of a Detailed Travel Plan by each individual tenant. In such circumstance it is generally appropriate for the Developer and Site Management Company to develop a ‘top down’ approach to the Travel Plan (as described above).

2.9. International Travel Plans and fiscal incentives

In other countries, a whole regulatory framework governs how businesses deal with getting their employees to work. In the USA, some State/Provincial, regional and local jurisdictions mandate so-called Commute Trip Reduction (CTR) programs for certain types of employers. Many transportation planning and transit agencies provided support for CTR programs, in a similar fashion to UK local authorities. Where a business or developer implements a CTR program it is possible that reduced parking requirements will be required.

According to Comsis Corporations (1993) & Winter and Rudge (1995), a comprehensive CTR program can reduce peak-period vehicular trips by as much as 10-30% at a work location. This can also be verified by work undertaken in the UK by Cairns et al in 2010. In Cairns’ study, 20 organisations that had implemented Travel Plans found that various measures used by employers to encourage employees out of their cars resulted in an overall reduction in the number of cars being driven to work of 14 per 100 staff.

Compared with the UK approach, the USA requires Travel Plans from virtually all employers in places where congestion and traffic pollution are a major problem. However, it has been argued that this overarching regulation has not resulted in Travel Plans being seen as a benefit; rather an additional cost (Enoch et al, 2003). In many European countries, governments have been working to reduce the financial burden of Travel Plans. In Norway, Germany and Belgium the tax system has been used to incentivise more sustainable modes relative to less sustainable modes of travel. In the UK, a similar system has been introduced whereby no tax or National Insurance Contributions are required, this includes (HMRC, 2012):

Free or subsidised work buses;

Subsidies to public bus services;

Cycle and safety equipment made available for employees; and

Workplace parking for cycles and motorcycles.

15

Although these changes to the UK tax system can be seen as a step in the right direction, they do not currently go as far as other European countries who have provided additional positive incentives to encourage staff to alter their travel behaviour. In order to demonstrate the benefit of the above tax ‘incentives’ it has been proposed that companies could complete an audit of their travel costs to demonstrate the financial benefit for adoption of a Travel Plan. As it stands currently the UK government has failed to use its tax system to provide any form of kick-start incentive to individuals or commercial organisations (Enoch et al, 2003).

Public institutions have so far led the way, but for widespread success as a policy tool, Travel Plans also need to be adopted by private sector employers. Local Authorities have been working to build links and produce guidelines and offering advice, however the vast majority of private sector employers do not have a Travel Plan in place and the vast majority still probably do not even understand the term or the implied concept (Coleman, 2000, p139-148). A study by T. Rye et al (2011) found that the guidance available to firms looking to implement a Travel Plan was excellent. However, the dissemination of guidance and the subsequent development amongst Local Authority offices has been piecemeal. T. Rye et al suggested that more active dissemination and training strategies, to include proactive communication and workshops led by planners who have successfully used the guidance are required if Travel Plans are to be successfully introduced on a wider scale.

2.10. Corporate social responsibilities

Since the Labour Government’s White Paper on transport policy was published in 1998, the aim has been to increase the widespread voluntary take-up of Travel Plans. However, even though many public sector organisations have now adopted Travel Plans, any policy mechanism to encourage voluntary take-up in the private sector has so far been relatively low-key (Enoch et al, 2003). The current half-hearted approach to travel planning is sending contradictory signals to businesses. Where the existing system does work, is getting Travel Plans onto a businesses’ agenda through planning consent regulation, but in these situations it could be argued that this is seen as a cost and not as something that businesses should undertake as part of their normal practice. As a general consensus transport will never be the core concern of the majority of employers, and so the current informational instruments that dominate UK policies are unlikely to be effective, unless they are supported by additional measures, such as a mix of planning regulation and fiscal incentives or penalties for non-participation (Enonch et al, 2003).

Although progress has been made in improving the travel planning process following the introducing of NPPF, the number of private businesses implementing and fore filling their obligations, either as part of a planning application or on a voluntary basis is still small. A study by T. Rye (2002, p287-298) concludes that the central reasons for non-implementation of Travel Plans in private businesses can be put down to the following:

16

Private sector businesses feel little need to lead by example, the main role of a company is to make profit and as such there is perceived to be no financial gain in implementing a Travel Plan;

Employees travel to work does not specifically present an employer with any problems in terms of the functioning of the business;

Often a business does not perceive any issue with transport or parking at or close to their site; and

There is insufficient evidence to prove that a Travel Plan of a given nature can generate a modal shift of a certain percentage and therefore there is no evidence to prove that spending any money would improve the situation locally.

In order to encourage the take up of Travel Plans and improve compliance, Enoch, et al (2003) identified four mechanisms targeted at the commercial sector to encourage their staff to commute in a ‘greener’ way:

1. Information and exhortation; 2. Regulation; 3. Subsidies; and 4. Fiscal incentives and/or penalties.

At the same time as considering the four mechanisms identified by Enoch et al, a business also needs to become an active instigator in linking the long-term benefits a Travel Plan can bring to the business, rather than planning for the short-term factors (Roby, 2010). In order to introduce the sustainable future concept, it is as much about changing policies to shift values as it is about changing practices. (Palmer, 1990). In the last two decades we have seen an increased awareness of ‘social responsibility’ within society, resulting in many companies reviewing the way their businesses operate. Kolk (2008, pp.1-15) in her study of multinational businesses sees a growing demand for transparency surrounding corporate behaviour. This has seen a move towards incorporating ethical and social issues within the traditionally financial aspects of corporate reporting, and has become known as either ‘corporate social responsibility’ or ‘triple bottom line reports’. Elkington (1999, p.24) talks further about the triple bottom line and how its purpose is to challenge and revolutionise how companies think and act. It is also about educating and changing the views of stakeholders and ensuring businesses improve their accountability. This is a move away from the traditional belief that businesses sole responsibility is concerned with only maximising profit.

However Milton Friedmen (1970) argues that businesses are not human beings and cannot assume true moral responsibility for their actions; his belief is that society’s best interests for achieving change lies with governments, not managers. Friedmen also argues that the current lack of legally binding obligations for a business to tackle commuter trip reduction is a major issue, which causes confusion and prolongs ignorance amongst businesses as to where their responsibilities lie. Wood and Ivens (1997, pp. 101-113) have studied these ideas further and in their research found that problems often

17

seen as social responsibilities will on inspection turn out to be political responsibilities, which the politicians are blind to, or afraid to tackle.

The problem with Travel Plans is unfortunately not confined to the need to increase the take-up of voluntary Travel Plans. In the UK, the issue of ‘greenwashing’ has developed. This is the process whereby a developer produces an impressive list of ‘environmentally friendly’ proposals, but then fails to implement them either effectively, or in the worst cases, at all. This is exacerbated further as a local authority can only serve the developer with a ‘breach of conditions notice’ and hope they comply. If funding has been secured through an obligation it is possible to enforce, but only through a quasi-court. T. Rye et al (2011) highlighted that even when a developer has not met one or more of their obligations, any challenge from a local authority could be counter challenged by a developer on the basis that they have done everything in their power to do so, and thus not acted unreasonably. Such an argument could undermine the basis of planning obligations and the use of monetary penalties for non-achievement of any associated targets. T. Rye’s study of local authorities that have taken enforcement action against a breach of Travel Plan conditions or obligations would appear to back-up this theory, with only four local authorities admitting to having begun proceedings against a developer. The survey also asked authorities how they would enforce planning conditions. 32 said they were not sure, whilst 54 did not answer the question.

Looking to the future, some progress has been made with businesses developing their own reports due to demand from stakeholders, shareholders and consumers, rather than in response to any direct government policy. In order to further enhance these changes, businesses will need to increasingly develop and implement zero emission activities linked to overarching business change - this will help Travel Plans become embedded in the wider business as a support measure of business planning - as opposed to a separate business objective (Roby, 2010). Holbeche (2001) describes business culture as something that results from a learning process of interaction, actions and processes built up on commonly accepted behaviours. Schein’s (1997) model of business culture places an emphasis on creating a supportive culture for the development of social responsibility in a concordant and non-contradictory way.

In a study conducted by Coleman (2000, p139-148), he identified that the issue of understanding the term Travel Plan as an implied concept is still holding back their widespread implementation. In a survey of businesses, around 38% indicated that public transport alternatives were important factors in enabling modal shift to be successful. 37% felt further central Government legislation was required, whilst 35% indicated that tax incentives would be needed before they took any action. Improved advice and information, along with business rate discounts and financial support were also seen as important (20%). As a result, Coleman suggested the following improvements to increase participation in Travel Plans:

Continued awareness raising of the term and concepts of Travel Plans is needed;

18

Widespread implementation of Travel Plans will be unlikely unless national legislation required it;

Targeting large businesses in urban/suburban location; and

If smaller businesses are to be targeted they should be looked at on an area basis rather than on an individual basis so that resources can be pooled.

Where Travel Plans have been introduced as part of a wider change towards corporate social responsibility, businesses will ultimately be the primary beneficiaries of a healthier and more prosperous environment. Taking a positive stance at this time can only improve the performance and position of a company through increased transparency and greater accountability. A successful business in Romme’s (1992, pp. 11-24) view will be the enterprising one that develops a range of measures and implements wider organisational change. This can then be used to deploy skills learned in the past to capitalise on the opportunities of the future, whilst meeting obligations to the environment. Corporate responsibilities are increasingly becoming a selling point for a company’s image; with the labelling of ‘socially responsible companies’ it is likely we will continue to see a shift where-by certain businesses become an active instigator of sustainable development, meeting Governments plans to increase the voluntary take-up of Travel Plans. On the reverse of this positive change, many firms are however still failing to make this adjustment. Without a move to a planning system, which is more proactive, simple and legally binding, Travel Plans are unlikely to produce more sustainable patterns of commuting in the foreseeable future.

2.11. Conclusion

From the literature that has been reviewed and researched, it is clear that Travel Plans are continuing to evolve, with competing pressures from global, national, and local policies still needing to be balanced to ensure the guidance released to Travel Plan developers is both concise and workable. The UK has continued to see the development of Travel Plans at a more local level, with the introduction and use of travel management software (iTRACE), car-pooling, offering on-site bicycles, and ecological driver training. However further development is still needed to link the process of planning, regulation and controlling of travel within a development, or business, including how a Travel Plan can be interconnected with the internal organisational goals of a business.

Helen Roby’s (LTT Issue 498 10 July, 2008) research demonstrated that Travel Plans are evolving on the basis of more localised agendas. This has seen some highway authorities, namely TfL (2012) demonstrating the need for Travel Plans to be linked into internal organisational goals, as opposed to just addressing an external regulatory agenda as per the national DfT guidelines:

19

DfT (national)

“A package of measures aimed at promoting sustainable travel within an organisation, with an emphasis on reducing reliance on single occupancy car travel.”

TfL (local)

“Travel planning is an effective business management tool which can be used to generate cost savings, lending companies a competitive advantage, and which has additional benefits for the environment and the health of employers.”

Unfortunately even after the introduction of the latest planning policy guidance (NPPF), it could be argued that an even stronger central government guide is required to steer developers and incentivise companies through fiscal means to embrace the introduction of Travel Plans within a development or organisation. The current situation surrounding the monitoring of Travel Plans is arguably farcical, making it virtually impossible for local authorities to prove in court that a site occupier has not fulfilled their obligations. This situation not only undermines the real purpose of Travel Plans, but also hinders their future development; not only at a planning level, but also at a voluntary level. The need for further change and a more consistent approach by local authorities across the UK has never been more important if we are to see any long-term benefit from Travel Plans.

As a result of the literature review and what I see to be the associated ‘gaps’ that currently exists within the travel planning world, this study will look to understand in greater detail how individual businesses and organisations have been dealing with their existing Travel Plan and then asking what they feel is required from both the national and local levels of government in order to support the future of Travel Plans.

20

3. Methodology

3.1. Introduction

In this chapter the chosen approach to this study’s methodology will be described. It will look at the reasons behind the choice of topic, and how the study has been designed to ensure the importance of looking at Travel Plans across the different geographical scales is not lost. It will also detail how the research will be undertaken and then analysed to understand how the data collected can be best used to answer the aims of the study.

3.2. Choice of topic

The choice of topic has been based around my previous experience with Travel Plans and my determination to understand why most Travel Plans in existence today are seen as a ‘box-ticking’ exercise to obtain planning permission, as opposed to a long-term solution designed to tackle increasing levels of personal mobility. What makes this topic more interesting is the global nature of the umbrella term ‘sustainability’, and the many different areas it is now seen to encompass, including: social, economic, and environmental factors. The focus on local and corporate social responsibility in this study has come about through my undergraduate studies. During my first degree I spent a great deal of time investigating the changing issues of corporate social responsibility, for this reason I wanted to look again at how things have continued to develop at the more local level and to see if more recent changes in government policy have brought about an increase, or even a potential decrease in the long-term success of travel planning.

3.3. Study design

The methods of research for this study were initially proposed in the Study Plan, which was prepared in May 2012. This identified the need to address a number of concerns relating to Travel Plans, for this reason the focus has been on three different levels: national, local, and corporate. Particular attention has been paid to the corporate level and contact has been made with a number of businesses through Kent County Council’s iTRACE database of Travel Plans. These contacts will be used to better understand how businesses setup their Travel Plan and the day-to-day requirements it places upon them. In order to answer the aims of this study, both qualitative and quantitative data will be collected from businesses that have introduced a Travel Plan. This will be supplemented with additional interviews conducted with employees of Kent County Council’s Planning and Sustainable Transport Team to better understand the local issues of implementing Travel Plans using past and current national policies.

To bring the local studies into context, this study has also been supplemented with information on planning policy and national guidance on Travel Plans. In the study design, both national and local inputs have been broken down to demonstrate how fragmented the current guidance is. The study has also

21

been designed to take account of all the different geographical scales needing to be addressed, working from the national to the local level.

Figure 01 - The research process (Bryman 2008).

Figure 01 illustrates the key stages that will be followed when conducting research. In this study both types of data will be collected, the qualitative data will bring a greater depth of understanding in relation to Travel Plans already in operation. The use of qualitative methods has become an increasingly important element of research and together with secondary data can result in valid pieces of research being produced (Marshall and Rossman 2010).

22

3.4. Qualitative data

One of the aims of this study is to gain a better understanding of Travel Plans at the local level. The use of qualitative data will support development of local understanding. It is at this very local context that one is able to ascertain feelings and attitudes towards Travel Plans and wider corporate social responsibilities. It will also be possible to further examine the initial responses provided through the online survey. Herbert (2000, p.550), describes the benefits of using more qualitative methods to gain insight into people’s anxieties and feelings, which are well suited to ethnographic enquiries:

“Humans create their social and spatial worlds through processes that are symbolically encoded and thus made meaningful. Through enacting these meaningful processes, human agents reproduce and challenge macro ecological structures in the everyday of place-bound action. Because ethnography provides singular insight into these processes and meaning, it can most brightly illuminate the relationships between structure, agency and geographical context.”

To provide a greater understanding of how Travel Plans operate at the local level, telephone interviews will be conducted with respondents who had indicated as part of the initial online survey that they would be happy to take part in a follow-up interview. These will be designed to generate a greater depth of understanding about respondents’ specific experiences and thoughts. As such, a semi-structured approach will be used. The themes each telephone interview will concentrate on are:

Responsibility for the Travel Plan (at creation, implementation and monitoring);

Measures implemented;

Overall success;

Any difficulties encountered;

Interaction with KCC; and

What could be done to improve the Travel Plan process?

23

The organisations that have agreed to take part in the follow-up interviews include:

Table 01 - Follow-up interview sites.

Site Business Type Type Location Respondent

One Highway engineering Private Business park Sustainable team

Two Property management Private Business park Park manager

Three Retail development Private Business park Consultant

Four Supermarket Private City Centre Consultant

Five Education Public Multiple locations Sustainability coordinator

Six Higher education Public Multiple locations Travel Plan coordinator and parking manager

Furthermore, the study focuses on Kent County Council and their Planning and Sustainable Transport Teams. By conducting interviews with KCC employees it will be possible to see the work being undertaken across numerous departments, and with district and borough partners to promote Travel Plans across Kent. This includes working to tighten up plans required as part of planning permission, and also voluntary Travel Plans that require further outreach to the wider business community. By conducting interviews at this level of local government, it is also possible to gather feedback on current national initiatives and any ideas or suggestions that might be employed by Kent to enhance and extend Travel Plans to the widest possible audience.

Through the use of qualitative data, it is anticipated the research available to draw a conclusion to the study will be much more detailed and bring a personal understanding from a range of different perspectives and geographical scales. The data has been collected from a wide range of sources including: structured qualitative telephone interviews; and face-to-face meetings. These findings will be used to back-up and challenge the more statistical findings from the quantitative data.

3.5. Quantitative data

This study has sought to collect quantitative modes of data in order to enable the use of mathematical modelling and statistical analysis techniques. These have been set within the wider context of this study to ensure they are of interest and come to life, adding authority to the argument, rather than analysis for the sake of it.

The data collected will come from contacts stored by Kent County Council as part of their iTRACE software, which manages Travel Plans within the County. This includes the contact details for either the site coordinator or the manager of the site who is creating the Travel Plan. A survey link will be sent to the list of contacts held on the iTRACE software, requesting their response about their experiences with their site Travel Plan. For the majority this will be sent

24

via email, with letters and phone calls to the remainder for whom no contact email address is available.

In designing the online survey particular attention will be paid to five key areas, including:

1. ‘Creation’ of the Travel Plan, comprising of the reasons why the Plan was developed and the key features implemented.

2. ‘Implementation’. This included questions on the actions carried out, as well as any problem, or parts that had not been implemented.

3. ‘Reviewing’. This is seen as important as initial research suggested that very little updating of Plans was being undertaken, the purpose of this questions was to ascertain if this was the case, and if so why.

4. ‘Engagement with other organisations’ was designed to see how much involvement third parties had from inception through to completion.

5. ‘Success of the Travel Plan’, or the reasons why it might not have been successful.

In addition to these main sections, questions will also be asked to gage awareness of current marketing tools being used by KCC to promote New Ways 2 Work and car sharing.

The use of quantitative data is an important aspect to this study. It will be integrated with other data collected to examine the difference between the online survey and telephone interviews. By having localised data, from a range of different businesses, it will be possible to understand more about the development and day-to-day operations of a Travel Plan.

3.6. Data analysis

In order to process and analyse the data collected in the most appropriate way for this study, all of the findings will be presented in a simple format. The idea is not to produce overly confusing statistics, but to use graphs that show the results, and allow for a comparison between businesses. Where it is possible to obtain a statistically significant result, this will be included within the results & analysis chapter. By doing this it will be possible to answer the main aims of the study, whilst allowing for a comparison to be made between the different findings. By writing up the structured telephone interviews undertaken with businesses and Kent County Council, it will be possible to take the salient points from each to see if there is any link between the two. The data and any findings can then be used to form the conclusion of the study. By bringing together the qualitative and quantitative research the study will have a range of crosscutting data to help answer the study aims.

3.7. Ethical considerations and data protection

Prior to conducting any form of primary research, the University of Westminster’s Code of Practice Governing the Ethical Conduct of Research 2011/2012 was read to ensure that due consideration was given to the potential ethical implications of any such research. It was decided that the primary data collected for this piece of research fell under ‘class one’ of the

25

code of practice, due to it having minimal, or no ethical implications. As a result no prior approval is required.

All respondents invited to take part in the survey will be invited to do so anonymously.

3.8. Conclusion

To summarise, this study will focus on organisations who have already introduced a Travel Plan in the county of Kent. This data will be supplemented by further follow-up telephone interviews with those organisations who are willing to provided further information. Interviews will also be conducted with key employees at Kent County Council. The in-depth interviews will be used to understand the current constraints surrounding Travel Plans, and what changes need to be made at either, or both a national or local level to enable organisations to comply with travel planning obligations.

26

4. Results & analysis

This chapter will compile results that have been collected and attempt to analyse them in order to answer the questions posed by the aims of this study. The three main areas covered by the results include:

1. Online survey;

2. In-depth telephone interviews; and

3. Kent County Council interviews.

4.1. Online survey responses

The online survey was devised to assist with answering the following aims:

To research how organisations are managing their Travel Plans;

To identify constraints within the travel planning process; and

To establish how Travel Plans can be improved.

Through accessing the Kent County Council iTRACE database, it was possible to attempt to make contact with a total of 253 organisations recorded as having implemented Travel Plans.

Table 02 demonstrates the district breakdown, and the public / private sector split. In total, 129 recorded Travel Plans were found to be un-contactable, due mainly to out-of-date information, or a lack of any contact detail provided from the outset. It has been assumed that the remaining 124 contacts were successfully contacted, however 31 responses to the online survey in total were received (Table 03); although only 24 of these were fully complete. This gave the online survey a response rate of 25%. This chapter will therefore present and analyse responses to the main questions asked within the survey whilst full results are available to view in Appendix A, along with the original responses.

Table 02 - KCC iTRACE database breakdown.

District Public Private Total

Ashford 3 56 59 Canterbury 7 8 15 Dartford 4 4 8 Dover 3 6 9 Gravesend 1 1 2 Maidstone 8 22 30 Sevenoaks 1 11 12 Shepway 1 7 8 Swale 1 13 14 Thanet 2 13 15 Tonbridge & Malling 5 53 58 Tunbridge Wells 5 18 23 Total 41 212 253

27

Table 03 - Online survey response breakdown.

Public Private Unknown Total

7 14 10 31

4.2. Creation

“Does anyone in your organisation have Travel Plan responsibilities as part of their job role?”

Figure 02 - Online survey responsibility responses.

In response to this question, 7 out of 13 organisations acknowledged that they did have a lead member of staff who managed their Travel Plan as part of their job role (Figure 02). Generally this was someone who was a sustainability manager, or coordinator, but responses also indicated that senior managers had been selected to ensure someone within a more strategic role managed their Travel Plan. Responses were also received from individuals who had taken on the role as a result of a personal interest. Whilst this result indicates a more positive perspective of Travel Plan management, it is important to acknowledge the study by Rye and MacLeod (1998) which recognised that employers must believe that there is a transport problem, which impacts upon their site and in addition to this, that they have a responsibility to solve it before they are likely to develop a greater form of ownership and accountability. The 42% that had no one responsible for their Travel Plan arguably still require further education to reinforce the important role a Travel Plan coordinate has to play, despite having been through the process. From the data collected it would seem that some organisations have recognised the potential a properly managed Travel Plan can bring. Where an external consultant is included within the mix the role of the Travel Plan coordinator seems to be much less focused, with less understanding and drive to ensure the Travel Plan meets its commitments.

28

Figure 03 - Online survey ‘why’ responses.

It was deemed important to drill down into the background and understand why an organisation originally created their Travel Plan. Question 4 (“Why did your organisation develop a Travel Plan?”) of the survey provided a range of options, including: planning condition, corporate agenda, cost savings and others (Figure 03). As anticipated the majority of the responses received were from those who had a planning condition, or agreement that required a Travel Plan as part of a planning application. Those who responded with ‘others’ provided a surprisingly clear understanding of a number of other important areas linked to Travel Plans. This contradicts Coleman’s observation in his study (2000), which found a lack of understanding of the term was one of the main reasons for holding back the wider introduction of Travel Plans.

The responses received showed a higher level of understanding, even beyond what a ‘standard’ Travel Plan might look to achieve. This included organisations trying to develop, or enhance their own green corporate agenda. Other responses identified the issues of parking, traffic congestion and even the need to reduce travel costs. One response went as far as to highlight that they had developed a Travel Plan to “aid occupiers of their site” (Appendix A - Online survey responses).

Whilst the results of this question are interesting and relevant, for those respondents who created a Travel Plan for reasons other than simply to comply with planning, in hindsight it would have been interesting to ask a follow on question related to the relative level of success a Travel Plan had in assisting the organisation to achieve their primary objective. For those simply fulfilling planning requirements, it would also have been interesting to discover if they have received any unexpected operational or other benefit from the Travel Plan.

29

Figure 04 - Online survey key features responses.

To understand more about the level of commitment each organisation had made to travel planning, respondents were also asked to identify the key features that had been implemented (Figure 04). The suggestions list included everything from a ‘do minimum approach’ e.g. providing public transport information, through to a more proactive organsiation who may have chosen to subsidise staff travel, or enhance their office facilities to help facilitate cycling to work.

The results demonstrate that the vast majority of organisations introduced four main features, these included: information boards showing sustainable transport options; car sharing; restricted, or priority parking; and enhanced facilities (e.g. showers, changing facilities, lockers). Information boards are generally seen as a ‘do-minimum’ approach, whilst the creation of enhanced facilities could generate increased modal shift. As a general rule none of the above options can be seen to have a greater positive impact over one or other. Organsiations can provide enhanced facilities, but without successful marketing and a pro-active approach the ‘do-minimum’ option could have a bigger impact than a poorly marketed priority-parking scheme. A large number of respondents also selected ‘other’, these responses further highlighted a number of increasingly pro-active responses to travel planning, including Cycle to Work schemes, eco-driver training, discussion and forum groups and incentivising staff through competitions. Given Kent County Council’s strong promotion of websites like kentjourneyshare and the Cycle to Work scheme, it is not surprising that such a high number of responses singled out these

30

options as one of their key features. This response could in someway suggest that the education methods adopted by KCC have resulted in some examples of success.

4.3. Implementation

In addition to trying to understand more about the creation process, the online survey also focused on the implementation phase. This can often be a stumbling block for an organisation, especially when the Travel Plan has been written on the basis of a wish list, rather than something that is affordable and viable. This was addressed in the subsequent question, “What actions from your Travel Plan have been carried out?”. The responses received generally mirrored the answers recorded in Figure 04, suggesting the key features identified within each organisations’ Travel Plan had been implemented.

Figure 05 - Online survey problems responses.

To gain additional insight into the implementation phase and to assist in answering the aims of this study, the online survey was also developed with the intention of understanding more about the problems faced when trying to implement a Travel Plan (Figure 05). This question received a response from 31 respondents, however only 7 identified having a problem during the implementation stage. This was a significantly lower proportion than had been anticipated given the results of studies by T. Rye (2002) and Coleman (2000), which clearly indicated a higher percentage of organisations struggling to successfully implement their original Travel Plan commitments.

Where an organisation identified a problem or problems they were asked to clarify what they saw as the main obstacles. The four key areas identified included:

Funding constraints;

Lack of interest;

31

Time limitations; and

Poor existing public transport links.

The above areas identified were seen to ultimately hamper trying to change employee attitudes.

After trying to establish what actions had been carried out, the survey set out to understand the actions, or key features that had not been implemented. Given the sensitivity of such a question and the potential implications for an organisation contravening a planning obligation, the question was designed to understand ‘why’, as opposed to ‘what’ had not been implemented (Figure 06).

Figure 06 - Online survey implementation problem responses.

Many of the constraining factors identified where more ‘typical’ of what might have been expected, for instance: time; and director sign-off. Unfortunately ‘N/A’ received the largest number of responses, which is potentially significant given the sensitive nature of the question, and an organisation potentially not wanting to make light of the fact they are yet to implement certain requirements.

4.4. Reviewing

A significant amount of any Travel Plan should be about monitoring and reviewing its performance. For this reason the survey included a section on ‘reviewing’. The key purpose behind this was to understand how many

32

organisations continued to monitor their Travel Plan once it has been created and implemented.

Figure 07 - Online survey updating responses.

The findings from this question demonstrated an even split between those that never updated their Travel Plan, verses those that updated their Travel Plan every 1-2 years (Figure 07). A much smaller number (5) responded with every 2+ years, whilst only 2 organisations stated they updated their Travel Plan more than once a year.

When asked what they did to update their Travel Plan, 2 organisations claimed to update their Travel Plan more than once a year, whilst 3 organisations stated they carried out on going monitoring. Two organisations did make mention of linking their Travel Plan with their wider corporate strategy. Where such organisations are linking a Travel Plan with their corporate agenda, it is possible to create a powerful document capable of delivering real organisational change, especially if the Plan is correctly implemented and all aspects are followed through from start to end. The single document can also be used to deploy skills learned in the past to capitalise on the opportunities presented in the future, whilst in addition meeting obligations to the environment (Romme, 1992).

33

Figure 08 - Online survey behavioural changes.

As well as asking about how often an organisation updated their Travel Plan, the survey focused on the uptake of monitoring surveys following the initial implementation. Interestingly, 55% of respondents reported that their organisation had undertaken follow-up reviews. As a consequence, a number of travel behaviour changes had been identified (Figure 08). However, next to car sharing the second most common answer was that there had been no change to travel behaviour, with one respondent saying, “people are selfish as ever” (Appendix A - Online survey results).

4.5. Engagement

Figure 09 - Online survey engagement responses.

34

To identify how improvements might be made, the survey asked questions around ‘engagement with other organisations’. This identified that an alarming 67% of respondents did not make any contact with another organisation as part of setting up their Travel Plan (Figure 09).