Can the agency costs of debt and equity explain the changes in executive compensation during the...

-

Upload

stephen-bryan -

Category

Documents

-

view

212 -

download

0

Transcript of Can the agency costs of debt and equity explain the changes in executive compensation during the...

Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535

www.elsevier.com/locate/jcorpfin

Can the agency costs of debt and equity explain the

changes in executive compensation during the 1990s?

Stephen Bryan 1, Robert Nash 2, Ajay Patel *

Babcock Graduate School of Management, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC 27109-7424, United States

Received 24 April 2005; received in revised form 25 August 2005; accepted 6 September 2005

Available online 19 October 2005

Abstract

Contracting theory predicts that greater equity-related compensation will decrease the agency problems of

equity but may exacerbate the agency problems of debt. We present evidence that the agency costs of debt may

have declined during the 1990s. Specifically, changes in the financial characteristics of our sample firms

suggest that underinvestment, asset substitution, and financial distress became less likely. Furthermore, agency

costs of equity increased during the 1990s, primarily because firms became more difficult to monitor. Together,

the findings provide an explanation for why more firms used option-based compensation in the latter 1990s,

and why the proportion of options in compensation structure increased throughout the decade of the 1990s.

D 2005 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

JEL classification: G34; J33; M52

Keywords: Agency costs; Executive compensation; Stock options

1. Introduction

Financial economists have long suggested that firms design management compensation

contracts to mitigate agency conflicts. In this paper, we examine how the agency problems of

debt and equity affect the firm’s compensation structure (i.e., relative amount of option-based

and cash-based compensation). Furthermore, through our analysis of both types of agency costs,

we provide an explanation for why more firms used option-based compensation and why the

relative use of option-based compensation increased during the 1990s.

0929-1199/$ -

doi:10.1016/j.

* Correspon

E-mail add

Ajay.Patel@m1 Tel.: +1 332 Tel.: +1 33

see front matter D 2005 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

jcorpfin.2005.09.001

ding author. Tel.: +1 336 758 5575; fax: +1 336 758 4514.

resses: [email protected] (S. Bryan), [email protected] (R. Nash),

ba.wfu.edu (A. Patel).

6 758 3671; fax: +1 336 758 4514.

6 758 4166; fax: +1 336 758 4514.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535 517

Using a large and detailed dataset covering 1992 to 1999, we find that the firm’s relative use

of option-based compensation is affected by both the agency costs of debt and equity. Previous

studies of compensation structure, summarized by Yermack (1995) and Bryan et al. (2000),

primarily focus on the agency costs of equity. Consistent with many of these papers, we find that

agency costs of equity (related to monitoring costs and abnormal firm performance) play a

significant role in explaining compensation structure during the 1990s.

Our study also highlights the role of agency costs of debt in the design of executive

compensation. The contracting literature identifies multiple agency problems of debt (each of

which involves a separate type of management action). However, prior empirical studies have

used a broad proxy (typically leverage) for all agency problems of debt. These studies, which

only use leverage as a proxy for all agency costs of debt, may be failing to disentangle the

differences in firm characteristics that contribute to these very different agency problems. In this

paper, we develop specific proxies to measure several stockholder/bondholder conflicts to

determine which agency cost of debt has the greatest influence on compensation contracts. Of

the specific agency problems of debt that we investigate, the asset substitution problem appears

most important in explaining the relative use of option-based compensation.

We also compare the early 1990s to the latter 1990s and present evidence of changes in the

potential severity of agency problems throughout the decade. When we compare the 1998–1999

period to the 1992–1993 period, our data suggest that the agency costs of debt declined and the

agency costs of equity increased. Both of these factors predict a greater use of option-based

compensation, a phenomenon we observe empirically.

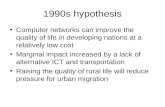

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops our hypotheses

regarding determinants of the structure of CEO compensation and defines the proxies we use in

our empirical tests. We specifically identify how agency costs of both debt and equity potentially

impact the firm’s design of management compensation contracts. Section 3 describes our data

sources and our sample. In Section 4, we present our results and, in Section 5, we provide a

summary and conclusion.

2. Agency costs and the structure of executive compensation

The following section briefly describes our hypotheses regarding how the agency costs of

debt and equity affect the design of managerial compensation contracts. We also introduce other

standard control variables identified as important by existing empirical studies. Table 1 contains

a summary of our agency-based hypotheses and the expected relation between the specific proxy

and the relative use of option-based compensation.

2.1. Agency costs of debt and the structure of executive compensation

Prior studies, such as Bryan et al. (2000) and Yermack (1995), use the firm’s leverage as a

proxy for all agency problems of debt. However, proxies that more clearly target specific

stockholder/bondholder conflicts should provide greater insights than the broad use of the

leverage variable (as an all-inclusive measure of every agency problem of debt). Therefore, we

develop separate proxies for specific agency problems of debt.

2.1.1. Underinvestment

Myers (1977) identifies a potential underinvestment problem for levered, high-growth firms.

Begley and Feltham (1999a,b) and Bizjak et al. (1993) contend that greater amounts of equity-

Table 1

Hypothesized relations between CEO option-based compensation and potential determinants

Hypothesis tested Variable Expected

sign

Variable description

Agency costs of debt:

(H1) Underinvestment (Market value /Book value)*

Short-term debt as percent

of total debt

+ [(Total assets — Book value of equity

+Market value of equity) /Total assets]

* (Short-term debt /Total debt)

(H2) Asset substitution (Market value /Book value)*

Convertible debt as percent

of total debt (CONV)

+ [(Total Assets — Book value of equity

+Market value of equity) /Total assets]*

(Convertible debt /Total debt)

(H3) Financial distress Altman’s Z-score (Z) + Altman’s (1993) Z-score is a weighted

sum of five ratios

Agency costs of equity:

(H4) Frequency of

external monitoring

Adjusted short-term debt as

percent of total debt

� Short-term debt /Total debt — Industry

average short-term debt /Total debt

Observability of

management effort:

(H5) Type of asset Market value /Book value

(MVBV)

+ [Total assets — Book value of equity

+Market value of equity] /Total assets

(H6) Size of firm Total assets (SIZE) + Natural logarithm of total assets

(H7) Firm performance Abnormal return on assets

(Abnormal ROA)

� ROA — Average ROA over preceding

three years, where ROA is defined as

EBITDA/Total assets

(H8) Free cashflow

problem

Free cashflow (FCF) + [Operating income before depreciation

— Interest expense� Income tax�Dividends] /Market value of equity

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535518

related compensation will further align shareholder/manager interests and will exacerbate the

underinvestment problem. However, Myers (1977) suggests that firms may reduce the

underinvestment problem by shortening the maturity structure of debt. If the debt matures

prior to the bexerciseQ date of the investment option, the firm will be less likely to forgo the

project and engage in underinvestment. Accordingly, firms with high growth opportunities that

use debt with a shorter average maturity should mitigate this stockholder–bondholder conflict

more effectively than similar firms that use mostly long-term debt.

We capture growth opportunities with the market value to book value of the firm’s assets. Our

calculation of the market value of total assets is the book value of total assets minus the book

value of equity plus the market value of equity. We use the proportion of short-term debt to total

debt to measure the maturity structure of debt. Our proxy for short-term debt is debt due to be

repaid in one year. The interaction term between the market-to-book ratio and the short-term

debt / total debt ratio provides an inverse measure of the agency cost of underinvestment. The

firm’s desire to help control this agency problem of debt leads to our first hypothesis.

H1. Firms with high growth opportunities that also use debt with a shorter maturity will use a

greater amount of option-based compensation.

2.1.2. Asset substitution

In a levered firm, stockholders may expropriate wealth from debtholders by switching from

safer to riskier investments. Begley and Feltham (1999a), Yermack (1995), and John and John

(1993) contend that asset substitution becomes more severe as management receives stronger

incentives to maximize equity value (e.g., when compensation is increasingly stock-based).

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535 519

John and John (1993), Agrawal and Mandelker (1987), and Green and Talmor (1986) argue

that the issuance of convertible bonds mitigates the asset substitution problem. In a firm with

convertible debt outstanding, incentives to transfer bondholder wealth to stockholders would be

reduced because the convertible investors hold the option to become shareholders and participate

in any increase in equity value.

The asset substitution problem is greater for firms with more growth options. We predict that

firms with higher growth options, that also use a large percentage of convertible debt, decrease the

agency costs of asset substitution to a greater extent than firms that use less convertible debt. We

follow Agrawal and Mandelker (1987) and measure the firm’s use of convertibles with the ratio of

convertible debt to total debt. Our measure of growth options is the market-to-book ratio. To

capture the agency costs of asset substitution, we construct an interaction term between the market-

to-book ratio and the use of convertible debt, as defined above. We expect a positive relation

between this interaction term and the proportion of options in the compensation structure.

H2. Since convertible debt mitigates the asset substitution problem, we expect a positive relation

between the convertible debt/growth option interaction term and the use of option-based compensation.

2.1.3. Effect of financial distress on agency problems of debt

Conflicts between bondholders and stockholders are especially prevalent in those situations

where it is uncertain that debtholders will receive promised payments from the firm. Bodie and

Taggart (1978) show that underinvestment will intensify during periods of financial distress

because more of a new investment’s value accrues to bondholders when default appears likely.

Additionally, John and John (1993) and Brealey and Myers (1991) note a greater likelihood of

asset substitution when the firm encounters financial distress.

Since financial distress exacerbates these agency problems of debt, firms prone to financial

difficulties should design executive compensation contracts that encourage managers to act more

like bondholders (i.e., managers should receive greater relative amounts of cash-based

compensation). As done by Denis et al. (2006) and Nash et al. (2003), we measure the

likelihood of financial distress by calculating Altman’s (1993) Z-score for each firm. The Altman

Z-score is a weighted combination of five ratios.3 Frequently used as a bankruptcy predictor,

lower values of the Z-score indicate a greater chance of encountering financial difficulties.

H3. Due to higher potential agency costs of debt, firms with a greater likelihood of financial

distress should use less option-based managerial compensation.

2.2. Agency costs of outside equity and the structure of executive compensation

In the following section, we describe major agency costs of outside equity and identify testable

hypotheses of how these conflicts may affect the design of executive compensation contracts.

2.2.1. Excessive perquisite consumption and managerial shirking

A portion of management’s utility stems from the consumption of perquisites or non-

pecuniary benefits. Also, the separation of ownership and control provides incentives for

managers to exert less than maximum effort. This agency problem of outside equity, known as

3 The components of the Z-score focus on the firm’s capital structure, asset utilization, profitability, and working capita

management. We alternatively measure the likelihood of financial distress with the Ohlson (1980) statistic. Results are

similar when we use the Ohlson statistic in our empirical analysis.

l

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535520

shirking, is similar to excessive perquisite consumption. Equity-based executive compensation

may mitigate these conflicts of interest by providing a more direct link between manager and

shareholder wealth.

Alternatively, Rozeff (1982), Easterbrook (1984), John and John (1993), and Malitz (1994)

note that direct monitoring by capital market participants disciplines managers to avoid

expropriation of shareholder wealth and lowers the agency costs of outside equity. Knowing that

they will be subject to continual scrutiny by external monitors provides incentives for managers

to avoid shirking and excessive perquisite consumption. Therefore, as Agrawal and Mandelker

(1987) contend, both external market mechanisms (monitoring in capital markets) and direct

contractual methods (compensation contracts) may help align stockholder/manager interests.

Comment and Jarrell (1995) suggest that the ratio of short-term debt (due to be repaid within

one year) to total debt is an indicator of the firm’s reliance on external capital markets. Firms

with higher ratios of short-term debt to total debt should more frequently access the capital

market to refinance the short-term debt. To determine the expected or normal value of a firm’s

short-term debt / total debt ratio, we calculate this ratio for all firms in the same 4-digit SIC code.

The difference between this expected ratio and that of the sample firm is a measure of the

abnormal, or adjusted, short-term to total debt ratio. Firms with higher adjusted values of short-

term debt to total debt should more frequently be monitored in the external capital markets and

should have lower agency costs of outside equity. This leads to our next hypothesis.

H4. Firms with a larger adjusted ratio of short-term debt to total debt should have lower agency

costs of outside equity and should use less option-based managerial compensation.

2.2.2. Growth options and the agency costs of equity

Firms with larger amounts of growth options should be more difficult to monitor and may

therefore have a greater potential for agency problems of equity. Jensen and Meckling (1976)

contend that the severity of a firm’s agency costs is affected by the amount of discretion in

managerial decision-making and the cost of measuring managerial performance. Bryan et al.

(2000), Kole (1997), and Bizjak et al. (1993) contend that firms with greater amounts of growth

options have broader informational asymmetries that create a larger potential for opportunistic

behavior by managers.

As a proxy for the prevalence of growth options, we use the ratio of the market value to the

book value of the firm’s assets. We expect that this variable will be positively related to the use

of option-based managerial compensation. This leads to our next hypothesis.

H5. Since they are more difficult to monitor, firms with greater amounts of growth opportunities

(larger market-to-book ratio) should use more option-based compensation.

2.2.3. Firm size and the agency costs of equity

Bryan et al. (2000), Yermack (1995), and Gaver and Gaver (1993) find that bigger firms pay

managers with significantly larger relative amounts of stock-based compensation. These authors

attribute this relation to the greater degree of difficulty in monitoring managers of larger

companies. Therefore, we predict a positive relation between firm size (as measured by the

natural logarithm of total assets) and option-based executive compensation.

H6. Since larger firms are more difficult to monitor, larger firms should use more option-based

compensation.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535 521

2.2.4. Firm performance and the agency costs of equity

As firm performance declines, relative to expectations, stockholders have an incentive to

better align the interests of managers. Consistent with this conjecture, Matsunaga and Park

(2001) find that firms reduce CEO cash bonuses when earnings fall short of analyst expectations

and previous firm performance. This suggests that the relative amount of option-based

compensation should increase when firm performance declines.

To test this hypothesis, we measure the firm’s performance as the abnormal change in ROA,

where ROA is EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) divided

by total assets. Abnormal ROA is the firm’s ROA in a given period less the average value for its

ROA over the preceding three years. We hypothesize that, as Abnormal ROA declines, the need

to better align managerial interests increases. Accordingly, the relative use of options in

executive compensation should increase. This leads to our next hypothesis.

H7. To provide stronger incentives for managers to maximize shareholder value, firms with

lower abnormal ROA should use more option-based compensation.

2.2.5. Free cashflow and the agency costs of equity

Jensen (1986) argues that larger amounts of excess cash lead to more severe agency problems

since discretionary cash may bemore likely to be invested in negative NPV projects or lost through

organizational inefficiencies. One method of motivating managers to optimally utilize excess cash

and maximize shareholder value is to provide greater amounts of equity-related compensation.

This leads to our final hypothesis. To measure the firm’s cashflow, we use the Lehn and Poulsen

(1989) cashflow statistic. Free cashflow is calculated as operating income before depreciation less

the sum of income tax, interest, and dividends. The amount of each firm’s free cashflow is scaled

by its market value (market value of equity and book value of debt). We expect that firms with

greater values of the free cashflow ratio should provide more option-based compensation.

H8. Due to the greater likelihood of sub-optimal investment, we expect firms with larger

amounts of free cashflow to use more option-based compensation.

2.3. Effect of other control variables on compensation structure

The contracting literature frequently includes other firm-specific control variables. These

control variables focus on CEO characteristics and firm-specific financial and operating

characteristics. The CEO variables are CEO’s age and percentage of equity ownership. The firm-

level variables measure liquidity, tax status, and profitability. See Berry et al. (2006-this issue),

Brick et al. (2006-this issue), Bryan et al. (2000), and Yermack (1995) for a thorough description

of the variables and the related hypotheses. We include these control variables (as well as year,

industry, and firm dummies) in every regression.

3. Data and methodology

In 1992, the SEC began requiring firms to disclose detailed information on executive com-

pensation in proxy statements. The required disclosures include CEO salary, bonus, stock options,

restricted stock, and long-term incentive plan bpayoutsQ, among other items. Stock options are almost

always granted bat-the-moneyQ, have a ten-year term, and vest over a 3–5 year period (Murphy

(1999)). In measuring the relative use of CEO stock option awards, we use the ratio of the Black–

Scholes option value to total compensation, where total compensation is defined as the sum of the

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535522

value of option-based compensation, restricted stock, long-term incentive plans, and cash com-

pensation (CEO salary plus bonus). Therefore, our primary measure of the structure of managerial

compensation is:

Mix1 ¼ Value of option compensation=Total compensation:

We also examine the robustness of our results using two additional measures of compensation

structure. The first alternative measure of managerial compensation, the ratio of option

compensation to cash compensation, is defined as:

Mix2 ¼ Value of option compensation=Cash compensation;

where cash compensation is the sum of CEO salary and bonus. This measure has been used

previously by Yermack (1995) and Bryan et al. (2000).

Another measure of compensation structure is the incentive intensity of executive

compensation. We define incentive intensity as the change in value of a CEO’s stock-option

award for every dollar change in the market value of the firm’s equity. We follow Yermack

(1995) and Bryan et al. (2000) in their definition of this variable.

Mix3 ¼ OptionVs delta 4ðshares represented by option award

=shares outstanding at the beginning of the yearÞ:

The Black–Scholes model provides an ex-ante value of the option awards. Our measure may

contain measurement error because firm-specific characteristics of the various option contracts

are not incorporated.4 Such measurement errors would reduce the power of our tests.

We obtain data on CEO stock option grants (the number of options) and CEO cash

compensation (salary and bonus) from Standard and Poor’s (S and P) ExecuComp database for

1992 to 1999. We include only firms that keep the same fiscal year-end to avoid a mismatch

between CEO compensation and the year to which it relates. The sample firms must also have

stock price information from the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) database and

have financial statement data available on Compustat. We use these data to directly calculate the

option value using the Black–Scholes model. Stock option value (OPTION) is estimated as:

OPTION T ; d; r; r;P;Xð Þ ¼ Pe�dTN d1ð Þ � Xe�rTN d2ð Þ;

where T is the expected term of the options (set equal to 10 years), d is the expected dividend

yield on the underlying stock over the expected term (measured as the dividend per share from

the prior year divided by stock price at the end of prior year), r is the expected volatility of the

underlying stock price over the expected term (measured as the standard deviation of 60 monthly

stock returns ending at the beginning of the year), r is the risk-free interest rate over the expected

term (estimated by the return on 10-year government securities), P is the fair market value of the

underlying stock on the date of the grant (set equal to the exercise price of the option, X), and N

is the standard normal cumulative distribution, and finally,

d1 ¼ r � dþ 0:5r2� �

T� �

=rffiffiffiffiTp

; and

d2 ¼ r � d� 0:5r2� �

T� �

=rffiffiffiffiTp

:

4 These characteristics include option forfeiture for early departure and different vesting schedules (Huddart, 1994;

Cuny and Jorion, 1995; Carpenter, 1998). Also, the Black–Scholes valuation methodology may overestimate the value of

the options granted to managers (Meulbroek, 2001). This is because managers tend to be undiversified. The market value

of the options in their compensation only rewards them for bearing systematic risk.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535 523

Our final sample includes 1623 firms with at least one year of data between 1992 and

1999.

Our methodology follows that of Bryan et al. (2000) and Yermack (1995). Not all firms grant

option-based compensation every year. Therefore, we test our hypotheses using a Tobit model

because of the preponderance of left-censored (at zero) stock compensation variables. Further, we

report the Tobit regression results using panel data, instead of estimating the model year-by-year, to

utilize all available information relating to year-to-year variation. Our models include proxies for the

agency costs of debt and equity aswell as other standard control variables. Dummy variables identify

any time-dependent, firm-specific, or industry-specific effects in executive compensation not

captured by our proxies for the agency costs of debt and equity or by our other control variables.

4. Empirical results

The following sections describe the results of empirical tests for our hypotheses regarding

determinants of the relative use of option-based management compensation.

4.1. Data description

Table 2 presents summary statistics for our primary measures of compensation structure

during the sample period. The first panel shows that, as a proportion of total compensation, the

average (median) option component is 0.268 (0.221) over the 1992 to 1999 period. In the second

panel, we see that the mean (median) ratio of option compensation to cash compensation over

the 1992 to 1999 period is 1.324 (0.357). This indicates that the average value of the options

granted, as measured by the Black–Scholes model, is over 132% of cash compensation.

Consistent with anecdotal evidence in the popular press and the findings in Bryan et al. (2000),

the option portion of executive compensation increased during the decade of the 1990s. The

mean (median) value of options as a percent of cash compensation increased from 89.6% to

179.8% (from 23.3% to 46.4%) between the 1992–1995 and 1996–1999 periods. As a percent of

total compensation, the average (median) value of option compensation increased from 21.5% to

30.2% (15.9% to 27.1%) over the same two sub-periods. Moreover, the number of firm-year

observations increased from 3363 in 1992–1995 to 5272 in 1996–1999. The two statistics

together suggest that more firms used options in their executive compensation, and that the

portion of options in the mix increased substantially from the earlier to the latter period. These

findings raise two important questions. First, why did more firms choose to use option-based

compensation towards the latter part of the decade of the 1990s? Second, why did firms increase

the proportion of options in executive compensation contracts during the 1996–1999 period

relative to 1992–1995?

Since we use agency costs of debt and equity to explain changes in the relative use of

option-based compensation, we begin by providing some basic analysis of changes in the

values of our explanatory variables.5 Table 3 provides summary statistics for our explanatory

variables during the 1992–1999 period. We also compare values of our explanatory variables in

the 1992–1995 and the 1996–1999 periods. Comparisons reveal little variation in the mean (or

5 Pair-wise correlations between the main independent variables are consistent with expectations. For instance, we find

that size has a significantly negative correlation with R and D, CEO ownership, and Altman’s Z; size is positively

correlated with dividends. Profitability is positively correlated with Altman’s Z and FCF, yet negatively correlated with R

and D. Similarly, R and D and FCF are also negatively correlated.

Table 2

Measures of compensation structure during the 1990s

Number of firm-year

observations

Proportion of option compensation to total compensation (Mix1)

Mean Median 1st quartile 3rd quartile

Data for years 1992–1999 8635 0.268 0.221 0.000 0.445

Data for years 1992–1995 3363 0.215 0.159 0.000 0.357

Data for years 1996–1999 5272 0.302 0.271 0.000 0.498

Number of firm-year

observations

Proportion of option compensation to cash compensation (Mix2)

Mean Median 1st quartile 3rd quartile

Data for years 1992–1999 8635 1.324 0.357 0.000 0.944

Data for years 1992–1995 3363 0.896 0.233 0.000 0.631

Data for years 1996–1999 5272 1.798 0.464 0.000 1.201

The sample consists of firms reporting compensation data on the ExecuComp database between 1992 and 1999 that also

have data on the Compustat and CRSP databases. The proportion of option compensation to total compensation (Mix1) is

the market value of stock option awards divided by total CEO compensation (salary, bonus, option compensation,

restricted stock compensation, and long-term incentive plan payouts). The proportion of option compensation to cash

compensation (Mix2) is the market value of stock option awards divided by the sum of salary plus bonus. Data for these

items are from the ExecuComp database. The table provides descriptive statistics for the full time period and two sub-

periods. The number of firm-year observations is the sum of the number of firms reporting data annually in each of the

time periods.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535524

median) value of firm size, free cashflow, or adjusted short-term debt to total debt. However, the

mean value of Altman’s Z-score, and the mean and median values of the market-to-book ratio

marginally increased between the 1992–1995 and 1996–1999 periods. Altman’s Z increased

from 4.697 to 4.925. Since Altman’s Z-score is a measure of the probability of financial distress,

our finding provides some evidence that the likelihood of financial distress decreased during the

latter years. This suggests lower agency costs of debt and is consistent with increased use of

option-based compensation. Furthermore, the market-to-book ratio increased from 1.861 to

2.204. A higher market-to-book ratio indicates an increase in the agency costs of equity. This

would also suggest a greater use of equity-related compensation.

4.2. Explaining the structure of executive compensation

In this section, we examine whether the agency costs of debt and equity are related to

the structure of executive compensation (i.e., the relative use of option-based and cash-

Notes to Table 3:

This table presents summary statistics for our explanatory variables. Data for the explanatory variables are from

Compustat, ExecuComp, and the SEC’s Edgar database. CEO Age is as reported by ExecuComp. R and D is research and

development expense divided by total assets. Tax is the firm’s simulated marginal tax rate (following Graham (1996)).

CEO Ownership is the percentage of firm equity owned by the CEO. Profitability is ROA (EBITDA divided by total

assets). CONV is the ratio of the book value of convertible debt issued by a firm to the book value of total debt

outstanding. Altman’s Z-score is a combination of five ratios based on Altman (1993). The market-to-book (MVBV) ratio

is the book value of total assets less the book value of equity plus the market value of equity divided by the book value of

total assets. Firm size is the natural logarithm of total assets. Free cashflow is the ratio of operating income before

depreciation less the sum of income tax, interest, and dividends paid to the firm’s market value. The firm’s market value

is measured as the sum of the market value of equity and the book value of debt. Abnormal ROA is ROA in year t less

the average ROA over the preceding three years. The dividend dummy variable has a value of 1 if the firm pays cash

dividends. Adjusted short-term debt is the firm’s short-term debt/total debt minus the industry average short-term debt /

total debt ratio.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535 525

based compensation). The standard errors from our regressions are robust to serial

correlation and heteroscedasticity, consistent with Yermack (1995) and Bryan et al.

(2000). The significance levels reported are from two-tailed tests using the robust standard

errors.

Table 3

Univariate data for explanatory variables

Variable Mean Q1 Median Q3

All years (1992–1999)

CEO age 57.843 53.000 58.000 62.000

R and D 0.016 0.000 0.000 0.018

Tax 0.332 0.309 0.365 0.395

CEO ownership 3.144% 0.090% 0.358% 2.071%

Profitability 0.142 0.098 0.145 0.199

CONV 0.063 0.000 0.000 0.002

Z 4.841 2.154 3.445 5.484

MVBV 2.080 1.172 1.513 2.227

Firm size 7.316 6.074 7.182 8.509

Free cashflow 0.053 0.037 0.054 0.076

Abnormal ROA �0.005 �0.029 0.001 0.028

Dividend 0.534 0.000 1.000 1.000

Adjusted short-term debt �0.019 �0.090 �0.022 0.028

Years 1992–1995

CEO age 59.680 55.000 59.000 64.000

R and D 0.016 0.000 0.000 0.017

Tax 0.343 0.309 0.368 0.397

CEO ownership 3.127% 0.083% 0.360% 2.188%

Profitability 0.146 0.104 0.147 0.199

CONV 0.062 0.000 0.000 0.000

Z 4.697 2.161 3.476 5.456

MVBV 1.861 1.115 1.479 2.099

Firm size 7.276 5.985 7.116 8.400

Free cashflow 0.056 0.039 0.055 0.076

Abnormal ROA �0.001 �0.023 0.002 0.031

Dividend 0.520 0.000 1.000 1.000

Adjusted short-term debt �0.021 �0.091 �0.022 0.030

Years 1996–1999

CEO age 57.149 52.000 57.000 62.000

R and D 0.016 0.000 0.000 0.017

Tax 0.327 0.310 0.363 0.394

CEO ownership 3.154% 0.093% 0.358% 1.973%

Profitability 0.139 0.096 0.144 0.200

CONV 0.063 0.000 0.000 0.000

Z 4.925 2.151 3.442 5.490

MVBV 2.204 1.038 1.532 2.350

Firm size 7.409 6.140 7.217 8.545

Free cashflow 0.052 0.035 0.054 0.076

Abnormal ROA �0.007 �0.033 �0.000 0.026

Dividend 0.544 0.000 1.000 1.000

Adjusted short-term debt �0.014 �0.089 �0.022 0.026

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535526

4.2.1. An agency cost of debt explanation

Model 1 (Table 4) indicates that the agency problems of debt significantly impact the

structure of executive compensation during the 1992–1999 period. The results in this model

indicate that the agency cost of asset substitution, as measured by the cross-product between

the market-to-book ratio and the ratio of convertible debt to total debt, is significantly

associated with the use of option-based compensation over the 1992 to 1999 period. As

predicted, the increased use of convertible debt reduces the asset substitution problem and

allows the firm to use more options in the compensation structure. Additionally, the likelihood

of financial distress (and the resultant impact on the agency costs of debt) significantly

impacts the relative use of option-based executive compensation. The data confirm the

expected positive relation between the Altman’s Z-score and the use of option-based

compensation. Finally, our results suggest that the potential for underinvestment (as proxied by

the cross-product between the market-to-book ratio and the ratio of short-term debt to total

debt) is insignificant during our sample period.

Table 4

An agency cost of debt and equity explanation of compensation structure

Independent variables Model 1

ACD

Model 2

ACE

Model 3

BOTH

Intercept 0.5341*

(0.0448)

0.0769

(0.0864)

0.0620

(0.0900)

CEO age �0.0034*(0.0008)

�0.0038*(0.0010)

�0.0036*(0.0011)

R and D 0.3426

(0.2194)

0.4805

(0.3169)

0.4175

(0.3243)

Tax 0.0035

(0.0042)

�0.0039(0.0115)

�0.0016(0.0112)

CEO ownership �0.0122*(0.0009)

�0.0109*(0.0013)

�0.0112*(0.0014)

Profitability 0.0677

(0.0574)

0.2347**

(0.1053)

0.1870

(0.1182)

Dividends �0.0996*(0.0129)

�0.1454*(0.0177)

�0.1425*(0.0183)

Market-to-book*(STD/TD) 0.0038

(0.0069)

0.0200

(0.0217)

Market-to-book*CONV 0.0953*

(0.0134)

0.0373***

(0.0205)

Altman’s Z 0.0034**

(0.0012)

�0.0015(0.0030)

Adjusted short-term debt /

Total debt

�0.0679(0.0504)

�0.1139(0.0704)

Market-to-book 0.0212*

(0.0042)

0.0226*

(0.0077)

Firm size 0.0333*

(0.0049)

0.0316*

(0.0054)

Free cashflow 0.1318

(0.1987)

0.4119**

(0.2019)

Abnormal ROA �0.4225*(0.1218)

�0.4556*(0.1264)

Number of censored observations 1899 1857 1842

Total number of observations 6435 6453 6300

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535 527

4.2.2. An agency cost of equity explanation

Model 2 examines the relation between the agency costs of equity and the relative use of

option-based compensation. The data indicate that the market-to-book ratio is significantly

positive. This is consistent with the hypothesis that firms with high market-to-book ratios are

harder to monitor, hence, have greater agency costs of equity. These firms use greater amounts of

options in the compensation structure to better resolve stockholder/manager conflicts. The firm

size variable is also significantly positive. This provides further evidence supporting our

hypothesis that larger firms should use more equity-related compensation. Finally, Model 2

presents evidence that corporations use option-based compensation to align stockholder–

manager interests when performance declines. The significantly negative coefficient on

abnormal ROA indicates that as performance declines, option-based executive compensation

increases. This finding is consistent with putting pay packages more at risk through increased

use of options in the compensation structure as performance declines (relative to historical

performance). Overall, our results suggest that several proxies for the agency costs of equity are

significantly related to the use of option-based compensation.

4.2.3. The combined impact of the agency costs of debt and equity

Model 3 (Table 4) indicates that both the agency costs of debt and equity are important

determinants of the relative use of option-based compensation. Of the agency problems of debt,

we find that asset substitution has the greatest impact on the use of options in executive

compensation. However, our proxies for the other stockholder/bondholder conflicts are no

longer significant in our combined model.

Notes to Table 4:

The sample consists of firms reporting compensation data on the ExecuComp database between 1992 and 1999 that

also have data on Compustat and CRSP. The dependent variable in each regression model is the ratio of the value of

stock option compensation to total compensation, where total compensation is the sum of the value of stock options

granted, the value of restricted stock, long-term incentive plans, and cash compensation, including cash bonuses. A

column heading of ACD indicates that the model includes the proxies for the agency costs of debt. A column heading

of ACE indicates that the model includes the proxies for the agency costs of equity. A column heading of BOTH

indicates that the model includes the proxies for both the agency costs of debt and equity. The total number of

observations is the sum of the number of firms reporting data for each time period. Data for the independent variables

are from Compustat, ExecuComp, and the SEC’s Edgar database. CEO age is as reported by ExecuComp. R and D is

research and development expense divided by total assets. Tax is the firm’s simulated marginal tax rate (following

Graham (1996)). CEO ownership is the percentage of firm equity owned by the CEO. Profitability is ROA (EBITDA

divided by total assets). The dividends dummy variable has a value of 1 if the firm pays cash dividends. The market-

to-book ratio is the book value of total assets less the book value of equity plus the market value of equity divided by

the book value of total assets. Short-term debt (STD) is debt due in one year, while total debt (TD) is the sum of short-

term debt and long-term debt. CONV is the ratio of the book value of convertible debt issued by a firm to the book

value of total debt outstanding. Free cashflow is the ratio of operating income before depreciation less the sum of

income tax, interest, and dividends paid to the firm’s market value. The firm’s market value is measured as the sum of

the market value of equity and the book value of debt. Adjusted short-term debt is the firm’s short-term debt / total debt

minus the industry average short-term debt / total debt ratio. Altman’s Z-score is a combination of five ratios based on

Altman (1993). Firm size is the natural logarithm of total assets. Abnormal ROA is ROA in year t less the average

ROA over the preceding three years. Each model also includes dummy variables for time, industry, and firm-effects

(results not reported). The regression results from a Tobit model are shown. Standard errors corrected for serial

correlation and heteroscedasticity are in parentheses.

* Denotes significance at the 1% level.

** Denotes significance at the 5% level.

*** Denotes significance at the 10% level.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535528

From an agency cost of equity standpoint, Model 3 indicates that the difficulty in

monitoring due to higher levels of growth options and larger firm size are significant

determinants of compensation structure. Also, as expected, the abnormal change in firm

performance (abnormal ROA) is significantly negatively related to the use of options in the

compensation mix. Furthermore, we identify a positive relation between option-based

compensation and the firm’s free cashflow. The debt maturity variable is never significant in

the models of Table 4.6

4.2.4. Control variables

We also control for CEO characteristics and firm characteristics that the extant literature

identifies as potentially affecting compensation structure. We find that CEO age is negative and

significant in each of the three regression models from Table 4. This negative relation is

consistent with that in Bryan et al. (2000) and in Yermack (1995). The tax status of the firm is

insignificant in all three regression models in Table 4. Profitability, as measured by the ratio of

EBITDA to total assets, is insignificant in two of the three regression models. This variable is

positive and significant at the 5% level in regression Model 2 only. Finally, as expected,

dividends, an indicator of the firm’s potential liquidity constraint, is negative and significant at

the 1% level in each regression model.

4.3. Alternative measures of compensation structure

To ensure the robustness of our results, we re-estimate our regressions using other functional

forms of the dependent variable. The following sections describe these results.

4.3.1. Using option compensation to cash compensation as the dependent variable

We re-estimate the models from Table 4 using the ratio of option value to cash

compensation (Mix2) as the dependent variable. Our findings using this definition of

compensation structure are essentially identical to those in Table 4. Again, our basic

conclusion is that both the agency costs of debt and equity are important in explaining the

time-series and cross-sectional variation of compensation structure (after controlling for the

standard CEO and firm-specific factors identified in the extant literature). Regarding the

agency costs of debt and equity, the findings are virtually identical to those we present

earlier.

4.3.2. Using incentive intensity as the dependent variable

Following the methodology of Yermack (1995) and Bryan et al. (2000), we re-estimate

the models in Table 4 using incentive intensity as the dependent variable. Our findings for

the control variables are essentially unchanged. The primary difference between our findings

using incentive intensity as the dependent variable and those in Table 4 concerns the

6 We also estimate the model using two alternative proxies of debt maturity structure. First, similar to Barclay and Smith

(1995), we measure debt maturity as debt maturing in three years or less as a percentage of total debt. Then, we use the debt

maturity variable of Stohs and Mauer (1996). We obtain similar results when using these two alternative proxies in our

empirical analysis. Themost notable differences occur when using the Stohs andMauer variable. All significant variables in

Model 3 remain significant when the Stohs and Mauer measure is included. However, the levels of significance change for

market-to-book and abnormal ROA (from 1% to 5%) and for free cashflow (from 5% to 10%). These differencesmay be due

to limited data availability since we lose 20% of our sample when using the Stohs and Mauer variable.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535 529

coefficient for firm size and the market-to-book ratio. The coefficient for firm size is

negative and significant under this specification. However, this finding is consistent with the

evidence documented in Bryan et al. (2000). We interpret our results in a similar vein to that

of Bryan et al., in that the relative use of option-based executive compensation increases at a

decreasing rate as firm size increases.

Moreover, we also identify that the market-to-book ratio is significantly negatively related

to incentive intensity in Model 2, but insignificant in Model 3. This result is consistent with

the findings in Yermack (1995). In addition, the data indicate that R and D intensity is

significantly positive in the regression equation. This result, too, was identified by Yermack.

Overall, the use of incentive intensity as the dependent variable does not alter our findings

regarding the agency-based determinants of compensation structure.

4.4. Further evidence of changes in the agency costs of debt and equity

The significant increase in the use of option-based compensation throughout the 1990s would

be consistent with an increase in the agency costs of equity and/or a decrease in the agency costs

of debt. The following section presents evidence regarding how these agency problems may

have evolved through the 1990s.

Our regression results indicate that asset substitution is the agency problem of debt that

has the greatest influence on the design of managerial compensation contracts. Also, an

increasing likelihood of financial distress, which exacerbates the agency problems of debt,

significantly affects compensation structure. These stockholder/bondholder conflicts are

primarily driven by the existence of risky debt. Debt becomes less risky as leverage in a

firm’s capital structure decreases. Table 5 shows a reduction in leverage for our sample

firms from 1992–1993 to 1998–1999. Regardless of whether we compute leverage relative

to total assets or relative to the market value of equity, leverage for our sample firms

Table 5

Changes in leverage, investment opportunities, and volatility over two sub-periods

Variable 1992–1993 1998–1999 P-value for difference

Leverage based on market value of equity 0.2984 0.2782 0.0554

Leverage based on total assets 0.3514 0.3354 0.0911

Market-to-book of total assets 4.1516 4.2535 0.0698

Market-to-book of equity 2.3974 2.4904 0.0318

Total risk 0.0138 0.0312 0.0001

Residual risk 0.0131 0.0276 0.0001

This table presents values for each of the variables over two sub-periods. We calculate two measures of leverage.

The numerator for both is the sum of long-term debt outstanding and long-term debt in current liabilities. For

leverage based on the market value of equity, the denominator is the market value of equity. For leverage based on

total assets, the denominator is the book value of total assets. The market-to-book of total assets is [Total

assets�Book value of equity+Market value of equity] /Total assets. The market-to-book for equity is the ratio of

the market value of equity to the book value of equity. For each firm, we compute an average value for each

variable over each two-year sub-period. We report values for the median firm in each sub-period. Total risk is the

variance of monthly returns for an equal-weighted portfolio of all firms in the sample over each two-year period.

Residual risk is the variance of the market model residuals, where the equal-weighted index from CRSP is

the proxy for the market. We estimate the market model using monthly returns for an equal-weighted portfolio of

all firms in our sample over each of the two-year periods. Tests for differences in medians are based on the

Wilcoxon test.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535530

decreased significantly between 1992–1993 and 1998–1999. Therefore, this decline in

leverage suggests a reduction in agency costs of debt, allowing for a greater use of option-

based managerial compensation. This is consistent with our findings in Table 2.

The agency costs of equity are primarily driven by the difficulty in monitoring the firm’s

activities. For example, agency theory predicts that firms with greater amounts of growth options

are more difficult to monitor. We examine two measures of growth options for our sample firms.

First, we compute the market-to-book ratio of equity. We also calculate the market-to-book ratio

of assets. As Table 5 indicates, both measures increased significantly from 1992–1993 to 1998–

1999, indicating larger agency costs of equity.

Additionally, the ability to monitor a firm’s activities also decreases as information

asymmetry increases. We use two measures of volatility as proxies for information

asymmetry. First, we compute the variance of monthly stock returns for an equal-weighted

portfolio of our sample firms over the 1992–1993 and 1998–1999 periods. Second, we

compute the variance of the market model residuals, with the CRSP equal-weighted index as

a proxy for the market. We estimate the market model using monthly returns over the

1992–1993 and 1998–1999 periods. Table 5 shows that volatility increased significantly for

our sample firms over the 1998–1999 period when compared with 1992–1993. This also

suggests an increase in the agency costs of equity.

Taken together, the results in Table 5 provide further evidence of a decrease in the

agency costs of debt and an increase in the agency costs of equity. Contracting theory

Notes to Table 6:

The sample consists of firms reporting compensation data on the ExecuComp database between 1992 and 1999

that also have data on Compustat and CRSP. The data are divided into two sub-samples. The first dataset

examined is for compensation data over the 1992 to 1995 period. The second sub-sample examined is

compensation data over the 1996 to 1999 period. The dependent variable in each regression model is the ratio of

the value of stock option compensation to total compensation, where total compensation is the sum of the value of

stock options granted, the value of restricted stock, long-term incentive plans, and cash compensation, including

cash bonuses. A column heading of ACD indicates that the model includes the proxies for the agency costs of

debt. A column heading of ACE indicates that the model includes the proxies for the agency costs of equity. A

column heading of BOTH indicates that the model includes the proxies for both the agency costs of debt and

equity. The total number of observations is the sum of the number of firms reporting data for each time period.

Data for the independent variables are from Compustat, ExecuComp, and the SEC’s Edgar database. CEO age is

as reported by ExecuComp. R and D is research and development expense divided by total assets. Tax is the

firm’s simulated marginal tax rate (following Graham (1996)). CEO ownership is the percentage of firm equity

owned by the CEO. Profitability is ROA (EBITDA divided by total assets). The dividends dummy variable has a

value of 1 if the firm pays cash dividends. The market-to-book ratio is the book value of total assets less the

book value of equity plus the market value of equity divided by the book value of total assets. Short-term Debt

(STD) is debt due in one year, while Total Debt (TD) is the sum of short-term debt and long-term debt. CONV is

the ratio of the book value of convertible debt issued by a firm to the book value of total debt outstanding.

Adjusted short-term debt is the firm’s short-term debt / total debt minus the industry average short-term debt / total

debt ratio. Free cashflow is the ratio of operating income before depreciation less the sum of income tax, interest,

and dividends paid to the firm’s market value. The firm’s market value is measured as the sum of the market

value of equity and the book value of debt. Altman’s Z-score is a combination of five ratios based on Altman

(1993). Firm size is the natural logarithm of total assets. Abnormal ROA is ROA in year t less the average ROA

over the preceding three years. Each model also includes dummy variables for time, industry, and firm-effects

(results not reported). The regression results from a Tobit model are below. Standard errors corrected for serial

correlation and heteroscedasticity are in parentheses.

* Denotes significance at the 1% level.

** Denotes significance at the 5% level.

*** Denotes significance at the 10% level.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535 531

models (such as from John and John (1993)) predict that these changes in agency costs

should lead to an increase in the relative use of option-based compensation. Our findings

are consistent with these theoretical predictions and with the recent empirical observations

that (1) more firms are using options in their compensation contracts, and (2) firms have

increased the relative use of option-based compensation through the decade of the 1990s.

4.5. The implications for changes in agency costs through time

We next focus on whether the determinants of compensation structure may change from year

to year. We base our specification of the two sub-periods on the following. First, by comparing

1992–1995 against 1996–1999, we investigate two periods of equal length. Second, the volume

of initial public offerings (IPOs) in the high-tech sector increased following Netscape’s IPO in

Table 6

Sub-period results for an agency cost of debt and equity explanation of compensation structure

Ind. variables Model 1

1992–1995

Model 2

1996–1999

Model 3

1992–1995

Model 4

1996–1999

Model 5

1992–1995

Model 6

1996–1999

ACD ACD ACE ACE BOTH BOTH

Intercept 0.3442*

(0.0860)

0.4957*

(0.0554)

0.0074

(0.1398)

0.2565*

(0.0846)

0.0331

(0.1493)

0.2391*

(0.0879)

CEO age �0.0027***(0.0014)

�0.0037*(0.0009)

�0.0024(0.0019)

�0.0043*(0.0012)

�0.0024(0.0020)

�0.0040*(0.0013)

R and D 0.3098

(0.3661)

0.3881

(0.2743)

0.3753

(0.5861)

0.6060***

(0.3655)

0.2491

(0.6054)

0.5487

(0.3692)

Tax 0.0024

(0.0068)

0.0040

(0.0054)

0.0107

(0.0127)

�0.0181(0.0150)

0.0122

(0.0125)

�0.0151(0.0161)

CEO ownership �0.0083*(0.0016)

�0.0142*(0.0011)

�0.0069*(0.0022)

�0.0130*(0.0017)

�0.0069***(0.0022)

�0.0134*(0.0017)

Profitability 0.3560***

(0.1910)

�0.0175(0.0653)

0.3614**

(0.1764)

0.1762

(0.1247)

0.3539*

(0.2114)

0.1563

(0.1393)

Dividends �0.1182*(0.0246)

�0.0911*(0.0150)

�0.1352*(0.0345)

�0.1473*(0.0207)

�0.1260*(0.0351)

�0.1451*(0.0215)

Market-to-book * (STD/TD) 0.0189

(0.0155)

0.0023

(0.0077)

0.1168**

(0.0494)

0.0112

(0.0227)

Market-to-book * CONV 0.0430

(0.0287)

0.0893*

(0.0152)

0.0194

(0.0455)

0.0427**

(0.0209)

Altman’s Z 0.0022

(0.0023)

0.0042**

(0.0014)

�0.0035(0.0064)

�0.0001(0.0033)

Adj. short-term debt /Total debt 0.0581

(0.1040)

�0.1145**(0.0546)

�0.1949(0.1370)

�0.1415**(0.0760)

Market-to-book 0.0120

(0.0154)

0.0237*

(0.0045)

�0.0010(0.0272)

0.0219*

(0.0081)

Firm size 0.0292*

(0.0090)

0.0353*

(0.0059)

0.0246**

(0.0104)

0.0345*

(0.0063)

Free cashflow �0.1572(0.1599)

0.3956***

(0.2150)

0.1478

(0.4786)

0.4471***

(0.2246)

Abnormal ROA �0.1914(0.2710)

�0.4563*(0.1389)

�0.1444(0.2670)

�0.4647*(0.1447)

Censored observations 697 1202 693 1164 684 1158

Total observations 1868 4567 1900 4553 1854 4446

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535532

1995.7 Changes in the mix of firms in the public domain from the first to the latter period could

cause variation in the explanatory power of different proxies for the agency costs of debt and

equity. Variation in sub-sample results would indicate that these findings are time-period

specific. Third, anecdotal evidence from the popular press and from institutional investors

appears to suggest that levels of equity and total compensation by the late 1990s appeared to

increase significantly. By examining the 1996 to 1999 period, we are able to determine whether

the cross-sectional and time-series variation in the use of option-based compensation is

consistent with theory, even if the levels of total compensation experienced large increases.

In Table 6, we find that CEO ownership and dividends continue to remain significant over

both sub-periods. However, CEO age is inversely related to compensation structure only during

the 1996 to 1999 period. This finding, that younger CEOs obtain more options in their

compensation, is consistent with (1) more high-tech firms being public over that sample, (2)

high-tech firms using more options in their compensation contracts, and (3) high-tech firms

employing younger CEOs than old economy firms. Moreover, this evidence indicates that our

findings in Table 4 and those in Bryan et al. (2000) are affected by the compensation structure at

firms during the more recent years.

We also identify that the ability of our proxies for the agency costs of debt to explain the

variation in compensation structure differs over the two sub-periods. During 1992–1995 (Model

1), none of our proxies for the agency problems of debt are statistically significant. However,

over the 1996 to 1999 period (Model 2), our proxy for underinvestment is insignificant, but our

proxies for asset substitution and financial distress are significant at the 1% and 5% levels,

respectively. Overall, these findings provide important insights regarding the impact of the

agency costs of debt on the design of compensation contracts during the 1990s. More

importantly, we identify which of the specific agency problems of debt have the greatest

influence on compensation structure.

Table 6 also presents our sub-period findings for the agency costs of equity. During the 1992

to 1995 period, only firm size is positive and significant (at the 1% level). However, over the

1996 to 1999 period, all five of our proxies for the agency problems of equity are significant.

These findings indicate (1) that the explanatory power of the agency costs of equity, in general,

and the specific agency costs, in particular, differ through time, and (2) that the variation in

compensation structure between 1996 and 1999 is better explained by theory even if the levels of

compensation increased during that period.

Our findings from the previous models continue to hold when we simultaneously examine

both sets of proxies. We present these results in Models 5 and 6 of Table 6. Overall, our evidence

suggests that the effect of various firm characteristics on compensation structure follows a

temporal pattern. This is consistent with the Smith and Warner (1979) contention that contracts

bevolveQ over time.

4.6. Other factors potentially affecting compensation structure during the 1990s

While we focus on the role of agency-based determinants, several authors have suggested that

other factors may have impacted the relative use of option-based compensation during the 1990s.

For example, Perry and Zenner (2001) find that restrictions on the deductibility of cash

7 Data on the number of IPOs on a monthly basis over our sample period are provided by Jay Ritter on his home page.

Ritter’s data indicate 8 internet IPOs over the 1992 to 1994 period, 13 internet IPOs during 1995, and 348 internet IPOs

between 1996 and 1999.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535 533

compensation greater than $1 million led to changes in the compensation structure for a subset of

firms. However, relative to all firms listed on ExecuComp (and included in our sample), the

number of affected firms is very small. Additionally, the new tax law was on the books

throughout a majority of our sample period and was therefore less likely to drive the changes in

compensation structure that we examine in the late 1990s. The wide-spread adoption of peer-

group benchmarking during the 1990s may have also contributed to changes in compensation

policy. A study by Bizjak et al. (2003) examines the practice of peer-group benchmarking and

reports that the use of benchmarking was pervasive during the 1990s. Also, unlike our study of

compensation structure (i.e., the relative use of option-based compensation), Bizjak et al. (2003)

focus only on the effect of benchmarking on the level of compensation Therefore, we do not feel

that our results are substantially affected by these alternative factors. However, the effects of

such changes in the institutional environment should be an important topic for future research.

5. Conclusion

We find that, as predicted by contracting theory, the relative use of option-based

compensation is related to both the agency costs of debt and equity. The specific agency

problem of debt that most influenced the structure of executive compensation is asset

substitution. From an agency cost of equity standpoint, our data confirm that larger firms and

firms with more growth options use greater relative amounts of option-based compensation.

Additionally, we find that abnormal changes in performance are negatively related to the use of

option-based compensation. This indicates that, as performance declines, the incentive to better

align stockholder/manager interests increases. Finally, we find that firms with greater amounts of

free cashflow use significantly more option-based compensation.

Additionally, we examine whether the agency costs of debt and equity may have changed

through the 1990s. In our analysis of the agency costs of equity, we find that the median market-

to-book ratio, total stock return volatility, and residual risk increased from 1992–1993 to 1998–

1999 for our sample firms. These results are consistent with an increase in the agency costs of

equity. The data also indicate a decrease in leverage for our sample firms, suggesting a reduction

in the agency costs of debt. Together, these findings provide evidence as to why the use of

option-based executive compensation increased through the 1990s.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anup Agrawal, Sudipta Basu, Sudip Datta, Kathleen Farrell, Aloke

Ghosh, Stu Gillan, LeeSeok Hwang, Mai Iskandar-Datta, Dirk Jenter, an anonymous referee,

and seminar participants at Baruch College, and session participants at the 2001 annual

meetings of the Financial Management Association and Southern Finance Association for

helpful comments. The authors also thank the Research Fellowship Program at Wake Forest

University’s Babcock Graduate School of Management for partial support of the project. The

usual disclaimer applies.

References

Agrawal, A., Mandelker, G., 1987. Managerial incentives and corporate investment and financing decisions. Journal of

Finance 42, 823–837.

Altman, E., 1993. Corporate Financial Distress and Bankruptcy. Wiley and Sons, New York.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535534

Barclay, M., Smith, C., 1995. The maturity structure of corporate debt. Journal of Finance 50, 609–631.

Begley, J., Feltham, G., 1999a. An empirical examination of the relation between debt contracts and management

incentives. Journal of Accounting and Economics 27, 229–259.

Begley, J., Feltham, G., 1999b. Theoretical analysis of the impact of debt covenants and CEO incentives on investment

decisions. Unpublished working paper. University of British Columbia.

Berry, T., Fields, P., Wilkins, M., 2006-this issue. The interaction among multiple governance mechanisms in young

newly public firms. Journal of Corporate Finance 12, 449–466. doi:10.1016/j.corpfin.2005.08.003.

Bizjak, J., Brickley, J., Coles, J., 1993. Stock-based incentive compensation and investment behavior. Journal of

Accounting and Economics 16, 349–372.

Bizjak, J., Lemmon, M., Naveen, L., 2003. Does the use of peer groups contribute to higher pay and less efficient

compensation? Unpublished working paper. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Bodie, Z., Taggart, R., 1978. Future investment and the value of the call provision on a bond. Journal of Finance 33,

1187–1200.

Brealey, R., Myers, S., 1991. Principles of Corporate Finance. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Brick, I., Palmon, O., Wald, J., 2006-this issue. CEO compensation, director compensation, and firm performance:

evidence of cronyism? Journal of Corporate Finance 12, 403–423. doi:10.1016/j.corpfin.2005.08.005.

Bryan, S., Hwang, L., Lilien, S., 2000. CEO stock-based compensation: an empirical analysis of incentive-intensity,

relative mix, and economic determinants. Journal of Business 73, 661–693.

Carpenter, J., 1998. The exercise and valuation of executive stock options. Journal of Financial Economics 48,

127–158.

Comment, R., Jarrell, G., 1995. Corporate focus and stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics 37, 67–87.

Cuny, C., Jorion, P., 1995. Valuing executive stock options with an endogenous departure decision. Journal of

Accounting and Economics 20, 193–205.

Denis, D., Hanuona, P., Sarin, A., 2006–this issue. Is there a dark side to incentive compensation? Journal of Corporate

Finance 12, 467–488.

Easterbrook, F., 1984. Two agency-cost explanations of dividends. American Economic Review 74, 650–659.

Gaver, J., Gaver, K., 1993. Additional evidence on the association between the investment opportunity set and corporate

financing, dividend, and compensation policies. Journal of Accounting and Economics 16, 125–160.

Graham, J., 1996. Proxies for the corporate marginal tax rate. Journal of Financial Economics 42, 187–221.

Green, R., Talmor, E., 1986. Asset substitution and the agency costs of debt financing. Journal of Banking and Finance

10, 391–400.

Huddart, S., 1994. Employee stock options. Journal of Accounting and Economics 18, 207–231.

Jensen, M., 1986. Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. American Economic Review 76,

323–339.

Jensen, M., Meckling, W., 1976. Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal

of Financial Economics 3, 305–360.

John, T., John, K., 1993. Top management compensation and capital structure. Journal of Finance 48,

949–974.

Kole, S., 1997. The complexity of compensation contracts. Journal of Financial Economics 43, 79–104.

Lehn, K., Poulsen, A., 1989. Free cash flow and stockholder gains in going private transactions. Journal of Finance 44,

771–787.

Malitz, I., 1994. The modern role of bond covenants. Unpublished working paper. Research Foundation of ICFMA.

Matsunaga, S., Park, C., 2001. The effects of missing a quarterly earnings benchmark on the CEO’s annual bonus. The

Accounting Review 76, 313–332.

Meulbroek, L., 2001. The efficiency of equity-linked compensation: understanding the full cost of awarding executive

stock options. Financial Management 30, 5–44.

Murphy, K., 1999. Executive compensation. In: Ashenfelter, O., Card, D. (Eds.), Handbook of Labor Economics. North-

Holland, Amsterdam.

Myers, S., 1977. Determinants of corporate borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics 5, 147–175.

Nash, R., Netter, J., Poulsen, A., 2003. Determinants of contractual relations between shareholders and bondholders:

investment opportunities and restrictive covenants. Journal of Corporate Finance 9, 201–232.

Ohlson, J., 1980. Financial ratios and the probabilistic prediction of bankruptcy. Journal of Accounting Research 18,

109–131.

Perry, T., Zenner, M., 2001. Pay for performance? Government regulation and the structure of compensation contracts.

Journal of Financial Economics 62, 453–488.

S. Bryan et al. / Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (2006) 516–535 535

Rozeff, M., 1982. Growth, beta, and agency costs as determinants of dividend payout ratios. Journal of Financial

Research 5, 249–259.

Smith, C., Warner, J., 1979. On financial contracting: an analysis of bond covenants. Journal of Financial Economics 7,

117–161.

Stohs, M., Mauer, D., 1996. The determinants of corporate debt maturity structure. Journal of Business 69,

279–312.

Yermack, D., 1995. Do corporations award CEO stock options effectively? Journal of Financial Economics 39,

237–269.