Buy Now! The Naval War Home on Lake · PDF filethe Kriegsmarine throughout their existence....

Transcript of Buy Now! The Naval War Home on Lake · PDF filethe Kriegsmarine throughout their existence....

36 World at War 28 | FEB–Mar 2013 World at War 28 | FEB–Mar 2013 37

The Naval War on

Lake LadogaBy Andrew Hind

Background

F or centuries Finland was part of imperial Russia, and only achieved independence in

May 1918 after a brief struggle that ended in the expulsion of Bolshevik troops from the new country. A portion of the border between independent Finland and its hostile neighbor ran through Lake Ladoga.

According to the terms of the 1920 Tartu Peace Treaty between Finland and Soviet Russia, both agreed not to operate military ves-sels of more than 100 metric tons displacement on the lake. Similarly, guns of all sizes above 47mm were banned, as was the creation of new military bases on its shores. The treaty ensured that for 20 years the lake remained relatively demilitarized.

Peace between the suspicious neighbors was shattered in October 1939, when the Soviets threatened invasion unless the Finns made territorial concessions. Among the Kremlin’s demands was the right to establish military bases inside Finland, Helsinki’s ceding of the islands of Koivisto, Suursaari, lavansaari and Tytarsaari in the Gulf of Finland, along with the Finnish part of the Rybachi peninsula in the far northeast on the Arctic Ocean, and a revision of the Finnish-Soviet border in Karelia some 20 miles northward. That last demand would place Lake Ladoga entirely under Russian control. The Finns refused on the grounds accession to the demands would’ve only worked to make their nation terminally vulnerable to future Soviet aggression.

continued on page 38 »

This is a classic photo from early in the Leningrad siege. It shows a skeptical looking resident of the city, most likely trying to gauge in his mind how he’s going to make that piece of bread in his hand—his entire food ration for that day—keep body and soul together.

A Siebel Ferry moving along the lake shore.

Buy Now!

Home

38 World at War 28 | FEB–Mar 2013 World at War 28 | FEB–Mar 2013 39

» continued from page 36 Once the Soviets began the

1939-40 “Winter War,” then, the Tartu Peace Treaty no longer held any legitimacy. Both sides were therefore free to remilitarize Lake Ladoga, but neither did so because its surface remained frozen and closed to navigation all through the brief war.

Though the Finns bloodied the Soviets during the fighting, they had

to make concessions to end the war. According to the resultant Treaty of Moscow, which ended the fighting, among other things, the border was indeed moved northward and Lake Ladoga became an internal Russian lake for the first time since 1918.

After the Winter War closed, the Finns looked for allies against the Soviets and they found them in Germany. Cooperation between Finland and Germany began in earnest

in the autumn 1940. Hitler was already preparing for his war of reckoning with the USSR, in which he saw Finland playing a supporting but nonetheless important role. As soon as Operation Barbarossa began, German aircraft flew from bases inside Finnish territory in support of the ground invasion, and the Finns advanced to recover the ter-ritory lost to the Soviets in 1940, as well as to incorporate East Karelia—histori-cally, ethnically and culturally part of Finland—into a new “Greater Finland.”

Even absent abetting the revenge of the Finns, the city of Leningrad held a fixation for Hitler. Aside from its industrial capacity (10 percent of the Soviet Union’s industrial output), he made it the target of one of Barbarossa’s main axes of advance because he considered his war against the Soviet Union an ideological crusade to crush communism. It had been in Leningrad, of course, that the Bolshevik revolution began in March 1917. Capturing the city would therefore strike a symbolic blow against the communists in addition to that acquisition’s industrial and geo-strategic benefits to the Third Reich.

From June to August 1941 Army Group North burst through defending

Red Army forces, raced through the Baltic states, and arrived on Leningrad’s outskirts. At the same time Finland attacked to the north of the city in order to recapture territory lost in the Winter War. By 2 September those Finnish forces had reached their nation’s former border, further isolating Leningrad.

Rather than engaging in what was anticipated as becoming a costly assault into a heavily defended city, the German high command elected to besiege Leningrad. There were over 300,000 Red Army troops inside the siege ring, along with a further 2.5 million civilians, so it was only a matter of time, the Germans believed, before Leningrad would be starved into capitulation.

The only supply path remaining for the city was across Lake Ladoga. As a consequence that water body became the scene of one of the war’s most unusual naval campaigns. The fate of millions rested on the outcome of a struggle waged by improvised flotillas, both consisting of relative handfuls of small warships that dueled across the cold waters of Europe’s largest lake in 1941 and 1942.

War on the Lake

The Finnish advance began on 29 June, and by 10 July the Soviet defenses north of Lake Ladoga had collapsed. As soon as their troops reached its shore, the Finns began to establish a flotilla there. The head-quarters of the new unit was set up in Laskela on 2 August, and by the 6th it included 150 requisitioned civilian motorboats, two tugs transformed into minelayers, and four steam ferries transferred from Helsinki by rail.

The tugs and ferries were armed with 47mm guns, while the other vessels were armed with an assortment of machineguns, many of them Maxims captured from the Soviets. The only true purpose-built warship on the lake was the Sisu, a motor-torpedo boat that dated to the pre-World War I era, which was railed in from the Gulf of Finland. In addition to that ad hoc assortment of vessels, the Finns established a number of coastal batteries along the shore and on some of the islands of the lake, deploying 88mm and 100mm guns supplied by Germany.

As Finnish land forces advanced

around the shore, the new flotilla pushed forward alongside them, set-ting up bases in newly captured towns. Lahdenpohja was taken on 10 August and Sortavala on the 15th. The Ladoga Flotilla’s headquarters was moved to the latter while the harbor at the for-mer became its primary base of opera-tions. Auxiliary bases were established at Sortanlahti, Kakisalmi and Salmi. The flotilla’s efforts were directed toward supporting and supplying the advancing ground force, denying use of the lake to the Soviets, and landing raiding parties behind enemy lines.

Despite performing well throughout the second half of 1941, by autumn the Ladoga Flotilla’s com-mand had to admit it was incapable of gaining complete control of the lake. Its southern portion remained open to Soviet shipping that sup-plied Leningrad with food, fuel and armaments. As long as that lifeline remained intact, starving the city into submission would be impossible. With winter approaching and ice begin-ning to form, there was nothing that could be done until the onset of the navigation season the following year.

Naval Detachment K

During the spring of 1942, Finnish Lt. Gen. Paavo Talvela, then in command their VI Corps, which was operating along the western shore of Lake Ladoga, concluded that a critical

war aim for the coming year would be ending the Soviet traffic providing supplies to Leningrad. His superiors saw things differently. In their view, Finland had already achieved its goals in the war and therefore should make no effort to further expand its role.

Talvela wouldn’t be deterred: he bypassed both the Finnish navy and armed forces general headquarters to present his proposal directly to the Germans. He requested German naval resources be allocated to Lake Ladoga to seal Leningrad’s fate by taking part in obtaining complete maritime supremacy over the water body. The Germans responded positively to his proposition, informing a surprised Finnish general headquarters that German and Italian naval units were going to be established on Lake Ladoga to assist them in enforcing the blockade of Leningrad.

With the break-up of the ice and the onset of the new navigation season, the combined Finnish-German-Italian unit, Laivasto-Osasto K (Naval Detachment K—“K” for Karelia) was officially created on 17 May. The first components to arrive were four Italian torpedo boats (526, 527, 528 and 529), which came by rail from Helsinki on 22 June.

Those boats were relatively new, having been built in 1939, and each displaced 20 tons. Driven by 2,000

continued on page 41 »

above — A Soviet supply boat being unloaded on the western shore of the lake.

below — Finnish infantry loading into small boats in preparation for a move along the lake shore.

Finnish sailors with a small patrol boat on the shore of the lake.

40 World at War 28 | FEB–Mar 2013 World at War 28 | FEB–Mar 2013 41

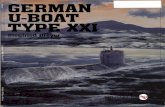

Siebel Ferries

Siebel ferries were originally intended for use in Operation Sea Lion, Germany’s planned 1940 cross-Channel invasion of Britain. They were the brain-child of aircraft designer and Luftwaffe officer 1st Lt. Fritz W. Siebel, who envisioned them as transport barges and floating heavy flak platforms for exclusive use by his service. As a consequence, they were operated by the Luftwaffe instead of the Kriegsmarine throughout their existence.

The shallow-draft ferries consisted of two heavy bridging pontoons (gotten from the army), which were braced together with iron cross beams and then covered by a wooden deck to create a catamaran-type vessel. Armor-reinforced structures protected the bridge and engines. For propulsion the ferries had a pair of Ford V-8 truck engines, with silent underwater exhaust in each aft pontoon end, connected to standard water screws. Additional power was to have come from three 600 horsepower aircraft engines mounted on elevated scaffolding on the rear deck. Those aircraft engines were soon removed, however, because they required too much maintenance and consumed large amounts of fuel.

The resultant boats displaced 140 to 170 tons, depending on each one’s exact configuration, and could travel up to 350 miles at eight to 10 knots while carrying loads of up to 80 tons. With a draught of no more than one meter, they were capable of operating in rivers, lakes and shallow littoral waters, while their low freeboard and wide flat decks meant they were easily configured for a variety of missions. Variants included headquarters, repair, hospital, heavy artillery, and light artillery ferries.

Easy to construct, the ferries were built in yards in Germany, Holland, Belgium and France. Sixty were ultimately constructed, serving in a total of five transport flotillas. Those units saw most of their service moving men and material between Sicily and Tunisia. ★

» continued from page 39

horsepower engines, they could reach speeds of 40 knots. They were each armed with two torpedo launch-ers, a 20mm machinegun, depth charges and smoke generators.

Five days later, four German KM-class minelayers also arrived. Those craft suffered from unreli-able engines and were crewed by inexperienced sailors, so it took until 10 August to get them fully operational. The Finns agreed to attach the Sisu to Detachment K, which was their only contribution to the joint command.

The Finns’ own Ladoga Flotilla was reinforced by the arrival of two German naval contingents: Luftwaffe-Fahrenflotillen II and III (Air Force Transport Flotillas). Those units had been formed in May 1940, in the Belgian port of Antwerp, for use in the planned invasion of England, but when that operation was cancelled they found themselves without purpose. They were redesignated as Einsatzstab Fahre Ost (EFO—Operations Staff Transport East) and sent to Lake Ladoga, where the unit acted inde-pendently but with close operational ties to Naval Detachment K.

The EFO consisted of nine infantry transports, 23 Siebel ferries (attack landing craft, see sidebar), and a heavy Sturmboot (assault boat), which acted as headquarters ship. The transports were each capable of carrying 50 fully equipped infantry-men. For the mission on Lake Ladoga, four of them were converted to

minesweepers; one became a hospital boat, another a headquarters, and three remained as transports.

The Siebel ferries were likewise modified: seven were made to carry heavy artillery, each mounting two, three or four 88mm guns and two 20mm multi-barrel anti-aircraft machineguns. Six were made into light artillery types mounting smaller caliber flak guns (generally one 37mm and two 20mm multi-barrel anti-aircraft machineguns). Six were kept as transports. Six were used as repair boats, and one was made into a headquarters vessel.

The command of the EFO fell to 1st Lt. Fritz Siebel, the Luftwaffe officer and engineer who’d originally come up with the concept for the unlikely warships. Siebel, despite having literally invented and engineered the unit he was commanding, had no operational combat experience with, nor any knowledge concerning the actual handling of, naval units. Worse, the men crewing his boats were all Luftwaffe personnel rather than sailors of the Kriegsmarine. As a result they were as inexperienced as their commander. The operational history of the EFO would come to reflect those deficiencies.

Opposing the Axis force on Lake Ladoga was the Soviet Ladoga Flotilla. Formed in October 1939 to assist in the Russo-Finnish War, under Capt. Vladimir S. Cherokov it proved a criti-cal logistical asset that kept the defense of Leningrad viable throughout the

late summer and autumn of 1941. Operating out of Noyoya Ladogo, on the lake’s southeast shore, the flotilla’s array of boats and barges, along with by a few motor-torpedo boats, ran supply convoys until ice closed the lake in November (when an improvised ice road was used). The flotilla also helped evacuate elements of 23rd Army in Karelia, which otherwise would’ve been trapped and destroyed along the western lake shore by the advancing Finns.

Over the winter of 1941/42, Leningrad’s shipbuilding facilities were put to use constructing ves-sels to augment the flotilla for the coming year’s effort. As a result, by the summer of 1942, just as the Italo-German force was arriving to reinforce the Finns, the Soviet Ladoga Flotilla got a dozen new warships, nine freighters and some 80 barges. That enabled it to daily transport over 5,000 tons of cargo across the lake.

Lake Combat

The first blow in the 1942 campaign for control of Lake Ladoga was struck not by naval forces on either side, but rather by the Luftwaffe. In May, while Naval Detachment K and the EFO were still organizing, for the first and only time during the Leningrad siege, Luftflotte I (First Air Fleet), which flew in support of Army Group North, made a major effort to disrupt Soviet logistics on the lake.

Artist’s concept of a Siebel Ferry taking part in its originally intended operation: shooting down British aircraft in Operation Sea Lion.

Typical Siebel Ferries

The officers in the photo are, from left to right: 1st Lt. Fritz Siebel, commander of the EFO; Finnish Col. E. Jaervinen, commander of that nation’s Lake Ladoga Coastal Brigade; and Gen. Alfred Keller, commander of Luftflotte I. The fourth officer is unidentified, though his red collar tabs likely make him a flak commander. Soviet gunboat “Bira” on Lake Ladoga.

Buy Now!

Home