Buy Now! Home - World at War | The Strategy & Tactics of ...€¦ · We’ll lose anti-tank guns...

Transcript of Buy Now! Home - World at War | The Strategy & Tactics of ...€¦ · We’ll lose anti-tank guns...

26 World at War 38 | oCT–NoV 2014 World at War 38 | oCT–NoV 2014 27

Rommel on Russia: His 1943 Solution for the Eastern FrontBy Gilberto Villahermosa

of staff of Rommel’s Afrikakorps and Panzerarmee Afrika commands. In light of Rommel’s tremendous experi-ence fi ghting a highly mobile war with a smaller force against quantitatively superior opponents better equipped and supplied, it’s worth pondering whether he’d arrived at a winning solution for the eastern front.

“You know Bayerlein, we have lost the initiative, of that there is no doubt,” Rommel began. “We have learned in Russia for the fi rst time that dash and over-optimism are not enough. We must have a completely new approach. There can be no question of taking the offensive for the next few years, either in the west or the east, and so we must try to make the most of the advantages that normally accrue to

The many formidable challenges facing the Reich at the time were at the forefront of Field Marshall Erwin Rommel’s and Lt. Gen. Fritz Bayerlein’s thoughts as they met at Hitler’s headquarters in East Prussia. “It was a few days after the failure of the collapse of the Belgorod-Kursk offensive,” remembered Bayerlein, “in which our attacking forces had become bogged down in the Russian anti-tank screens and defenses, and the bulk of our latest tanks had been lost. And with that had gone all hope of a new summer offensive in Russia.”

After a personal meeting with Hitler, Rommel sat with Bayerlein and discussed the general military situation. The two were old acquain-tances: Bayerlein had served as chief

B y mid-1943 the Third Reich was being assailed from east, west and above. Still, Germany

was far from beaten. At that time the Wehrmacht numbered almost 9.5 million personnel, with the majority, almost 6 million, serving in the army. Those soldiers formed around a battle-hardened core of veterans who held together the rest of the armed forces. They were still relatively well equipped, especially at the small-unit level, and they were led by many brilliant, or at least competent, offi cers and NCOs. Further, the expansion of the Waffen SS, from 160,00 in 1941 to 450,000 in 1943, provided a further hard core of young, well trained, well equipped and fanatic soldiers sworn to fi ght to the death.

the defense. The main defense against the tank is the anti-tank gun; in the air we must build fi ghters and still more fi ghters and give up the idea for the present of doing any bombing ourselves. I no longer see things quite as black as I did in Africa [when it was lost to us], but total victory is now, of course, hardly a possibility.”

Rommel told Bayerlein that Germany must fi ght on interior lines, and then expounded: “In the east we must withdraw as soon as possible to a suitable prepared line. But our main effort must be directed toward beating off any attempt of the Western Allies to create a second front, and that is where we must concentrate our defense. If we can once make their efforts fail, then things will be brighter for us.”

The German forces on the eastern front at the time Rommel said that numbered approximately 2.6 million soldiers and consisted of some 122 infantry divisions, approximately 25 panzer divisions (and one separate brigade), and another 17 miscel-laneous divisions and another brigade. (Many of the “miscellaneous” divisions were “Luftwaffe fi eld divisions,” which had originally not been intended for frontline operations but, rather, for security missions at airfi elds and throughout the rear.)

All those formations together were responsible for defending a long and meandering front that ran more than 1,500 miles from Leningrad in the north to the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea in the south. Many of the divisions,

however, were already offi cially listed as Abgekaempft (“fought out”), and were thereby acknowledged to possess only negligible combat value. A further number still fought effectively, but only as kampfgruppen (“battle groups”) of regimental or battalion sizes. At the same time the Germans had 12 divisions committed in Italy, while in the west there were 46 divisions and two separate regiments operational, with another seven divi-sions in the process of being formed. “Th[os]e fi gures strikingly reveal the strain exerted by the Russian war,” notes the offi cial US Army history of World War II. “The number of divisions in the east that needed

continued on page 30 »

This is offi cial Soviet-era war art, simply titled the “Battle of Kursk.” It depicts the moment of the fi nal defeat of the German spearhead in that failed offensive. It was the singular event, even more so than the Stalingrad debacle that

preceded it, which caused Hitler and his fi eld marshals to understand they needed a new strategy.

26 World at War 38 | oCT–NoV 2014 World at War 38 | oCT–NoV 2014 27

Buy Now!

Home

28 World at War 38 | oCT–NoV 2014 World at War 38 | oCT–NoV 2014 2928 World at War 38 | oCT–NoV 2014 World at War 38 | oCT–NoV 2014 29

30 World at War 38 | oCT–NoV 2014 World at War 38 | oCT–NoV 2014 31

worth noting that at no time in the war did German industry succeed in producing the 7,000 aircraft a month promised by Hitler. In 1943 German industry was producing slightly more than 2,000 aircraft a month; by 1944 that number would grow to more than 3,300 a month, but that was still less than half of what had been pledged by the Fuehrer. In comparison, German tank production in 1943 reached 1,650 vehicles a month and then climbed to 2,275 a month in 1944, exceeding Hitler’s promise.

Rommel went on to propose to Bayerlein his own “new approach” to the war on the eastern front: “Now I’ve made a careful study of our experi-ences in Russia,” he announced. “The Russian is stubborn and infl exible. He will never be able to develop a well thought out, guileful method [like the one] with which the Englishman fi ghts his battles. The Russian attacks head on, with enormous expenditure of material, and tries to smash his way through by sheer weight of numbers. If we can give the German infantry division fi rst 50, then 100, then 200, 75mm anti-tank guns each, and install them in carefully prepared positions

covered by large minefi elds, we shall be able to halt the Russians. The anti-tank guns can be quite simple; all that is necessary is they should be able to penetrate any Russian tank up to a reasonable range and at the same time be usable as an infantry gun.”

He continued: “Now let us suppose the Russians attack in a heavily mined sector where our anti-tank guns are forming a screen, say six miles deep. They – for all their mass of material – are bound to bog down in the fi rst few days and, from then on, they’ll have to gnaw their way through slowly. Meanwhile we shall slowly be installing more anti-tank guns behind [our own front line]. If the enemy makes three miles progress a day, we’ll build six miles depth of anti-tank screen and let him run himself to a standstill. We’ll be fi ghting from the cover of our positions; he’ll be attacking in the open. We’ll lose anti-tank guns and he’ll lose tanks. To move the guns we can use Russian horses or any other makeshift we can lay our hands on. That’s what the Russians do and we must adopt their methods. Once it becomes clear to the troops they can hold their ground, morale will go up again….Tanks, precision anti-tank guns, and all kinds of other things will have to be cut down. Our last chance in the east lies in equipping the army thoroughly for an unyielding defense.”

In sum, then, after having denigrated the Russian way of war, Rommel was suggesting entirely surrendering the strategic initiative to them, at least until the Anglo-Allies had been defeated.

First, then, there was really nothing “new” in Rommel’s idea. It was the same strategy being formulated by Hitler at the time. Rommel was simply parroting his Fuehrer.

Second, and more important, Rommel had never fought the Red Army. It was therefore natural for him that, having been defeated by the British at El Alamein, he thought of those Westerners as constituting the better army. Of course, the Soviet armed forces had just performed with competence at Kursk, fi rst on the strategic defensive and then in the counteroffensive that followed.

Hitler and his fi eld marshals had been traumatized by that recent experience at Kursk, and had also been tremendously impressed with not only the depth of the Soviet defense

there, but also with the density of minefi elds, anti-tank gun emplace-ments, artillery and armored vehicles deployed by the Red Army. Even so, rather than crediting Stalin and his commanders with skill and tenacity, or the Red Army with possessing superior technology in some fi elds and using increasingly effective strategy and tactics, they chose instead to focus on the technical reasons for their defeat: the depth of the defensive positions and the masses of anti-tank guns and mines around Kursk.

The reason they made that judg-ment aren’t diffi cult to fathom. By 1943 Hitler couldn’t change either the overall correlation of forces on the eastern front or the level of technology used by the Wehrmacht in the fi ghting there. What he could do, in light of the German Army’s shortage of men and material, was to build defensive lines and positions in order to conserve manpower and steel and replace them with more abundant concrete. What

Rommel proposed to Bayerlein was, in essence, that the Germans attempt to mimic the Soviet defensive strategy at Kursk across the entire front.

Even before Rommel’s discussion with Bayerlein on how best to fi ght in Russia, the Wehrmacht had been forced to transition from the strategic offensive to the defensive, relying on extensive series of fortifi ed positions and lines to try to stop the Anglo-Allied advance in the west. On Sicily the Germans and Italians had built three lines that ran from the northern to the eastern coasts of the island: the Main Defense Line (farthest southwest), the Etna Line, and the New Hube Line. That series of lines enabled the German forces on the island to slow the Allied advance and then evacuate Sicily across the Straits of Messina to the Italian mainland.

In Italy proper the Germans would utilize an extensive series of fortifi ed lines running from the Tyrrhenian Sea in the southwest to the Adriatic

territory even on a major scale, without suffering a mortal blow to Germany’s chance for survival. Not so in the west!” the Fuehrer would exhort. “If the enemy here succeeds in penetrating our defenses on a wide front, conse-quences of staggering proportions will follow within a short time.”

Rommel continued in his own discussion with Bayerlein: “We’ll soon be producing an enormous amount of war material. A few days ago the Fuehrer told me that by the beginning of 1944 we can expect to have an output of 7,000 aircraft and 2,000 tanks a month. If we can only keep the Americans and British off for two more years, to enable us to build up centers of gravity in the east again, then our time will come. We’ll be able to start drawing blood from the Russians once more, until they allow the initiative to pass more and more back to us. Then we’ll be able to get a tolerable peace.”

Generally a skeptic when it came to believing Germany could win the war after the loss of his African com-mand, Rommel tended to change his mind, at least temporarily, whenever he came under the direct personal infl uence of Hitler. Even so, it’s also

» continued from page 27

replacement and reconstitution was greater than the total number of divisions in the two western theaters.”

Thus, despite the thousands of replacements poured regularly into the divisions on the eastern front, the German ground force in Russia was becoming an increasingly hollow one. Facing that force was a Red Army with a total strength of 10 million (including 6 million frontline soldiers), and fi eld-ing some 581 division-equivalents of all types. That massive army was sup-ported by more than 13,000 tanks and assault guns (including almost 5,000 in reserve and training commands), along with 100,000 artillery pieces and mortars and 13,000 combat aircraft

Rommel had conferred with Hitler prior to his meeting with Bayerlein, and he was no doubt repeating what the Fuehrer had told him as well as anticipating Hitler’s Directive No. 51,which would be offi cially published on 3 November 1943. In it Hitler refocused the Wehrmacht on preparing for an Anglo-Allied invasion in the west. “In the east, the vastness of the space will, as a last resort, permit a loss of

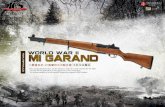

A German crew manhandling a 75mm gun somewhere in Russia in the autumn of 1943. About 200,000 more of them would’ve been necessary to carry out Rommel’s proposed strategy.

The German 75mm anti-tank gun, one of their classic weapons of the second half of the war.

A German 75mm anti-tank gun in use against the Anglo-Allies in Tunisia early in 1943. They weren’t just needed in the east.

Buy Now!

Home