buttigieg spare parts

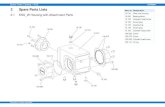

-

Upload

rui-videira -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

Transcript of buttigieg spare parts

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

1/22

743

Vertical Agreements and Concerted Practices in the Motor

Vehicle Sector under EC Competition Law Implications for

European Consumers

EUGENE BUTTIGIEG*

1. Introduction

For several years successive motor vehicle distribution and servicing block exemp-tions1 have came in for some harsh criticism from consumer organizations amongst

others.2 For instance, the British National Consumer Council noted that the practice

sanctioned by the erstwhile block exemption of manufacturers and importers fran-

chising dealers to sell only one make of product in an exclusive geographical area was

making it very difficult for consumers especially in rural areas to compare one brand

with another as they were compelled to visit different dealers to see each make. 3

The argument for maintaining this system of distribution was that the difficulties

for consumers in making brand comparisons were compensated for by the high stand-

ards of after sales service that the franchising of dealers in this way provides for.

However, consumer organizations have shown through market studies in Britain,

France and Germany that franchised dealers charged much higher prices for servicing

cars bought through them and provided no better service than independent garagesoutside the dealer networks that charged much less for servicing their cars.

Indeed these distribution and servicing agreements were purposely 4 left out from

the general block exemption on vertical restraints5 probably because, since the motor

1 Commission Regulation 123/85 on the Application of Art 85(3) of the Treaty to Certain Categories

of Motor Vehicle Distribution and Servicing Agreements [1985] OJ L15/16; Commission Regulation

1475/95 on the Application of Art 85(3) of the Treaty to Certain Categories of Motor Vehicle Distribution

and Servicing Agreements [1995] OJ L145/25.2 S Locke The Supply of New Cars and the EU Block Exemption (1994) 4 CPR 1.3 National Consumer Council Response to the Commission of the European Communities Green

Paper on Vertical Restraints in EC Competition Policy (NCC London 1997) 16.4 It was the intention from the outset as indicated in the Commission Green Paper on Vertical

Restraints in EC Competition Policy COM(96)721 that preceded the new block exemption on vertical

restraints. In its press release (IP/00/520) the Commission explained that this was primarily due to the fact

that Commission Regulation 1475/95 (n 1) had only been in force for two years when the review of policy

on vertical restraints was launched in 1997. K Middleton The Legal Framework for Motor Vehicle Distri-

bution A New Model? (2001) 22 ECLR 3 opines however that given the complexity of motor vehicle

distribution agreements in the EU and the controversy surrounding the renegotiation of the preceding

Commission Regulation 123/85 (n 1) it is more likely that the exclusion was a policy decision.5 CommissionRegulation2790/1999onVerticalAgreements andConcerted Practices [1999] OJL336/21.

* LL.D. (University of Malta); LL.M. (University of Exeter); Ph.D. Candidate, Institute of

Advanced Legal Studies, University of London. Senior Lecturer, Department of European and Compar-

ative Law, University of Malta.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

2/22

744 EUGENE BUTTIGIEG

vehicle distribution is an economic sector where there are still significant price differ-

entials between the Member States so that it is fair ground for parallel importation, it

was deemed advisable for vertical agreements in this sector to continue to be

governed by an ad hoc regulation that is specifically devised to protect and encourage

parallel importation by consumers of new motor vehicles without however opening

the door wide open to parallel imports by distinguishing between authorized interme-

diaries and independent resellers.6

Central to the selective and exclusive distribution system sanctioned by the block

exemption was the suppliers refusal to supply new cars to retailers other than its

franchised dealers, the associated prohibition on dealers from reselling except to final

customers and other dealers in the manufacturers network, the granting of exclusive

territories to dealers and the requirement that dealers sell exclusively one brand of

new cars. Dealers were required to provide servicing and repair services. Dealeragreements would of course then typically contain other restrictions and obligations

beyond the ones mentioned in the block exemption concerning matters such as sales

targets, advertising and promotion.

Vertical restraints between producers and distributors can have both pro- and anti-

competitive effects that may respectively benefit or harm consumers. In particular

such agreements may enable producers to penetrate into the new markets that Euro-

pean integration brings about (penetration of new markets takes time and investment

and is risky), thereby increasing consumer choice, and enhance efficient distribution

at the local level with appropriate pre- and after-sales support all to the benefit of

consumers. On the other hand, however, such arrangements may also be used to

partition the market and exclude new entrants at the production and distribution level,

preventing an intensification of competition that would lead to downward pressureon prices. Thus, vertical agreements can be used either pro-competitively to promote

market integration and efficient distribution or anti-competitively to block integra-

tion and competition. In the motor vehicle industry, the price differences between

Member States provide the incentive for firms to enter new markets as well as to erect

barriers against new entrants. So the block exemption sought to strike the right

balance to permit only such vertical restraints as would generate pro-competitive

effects.

The European Commissions report on the evaluation of Regulation 1475/957

showed that the selectivity features of a motor vehicle distribution agreement based

on qualitative as well as quantitative criteria effectively allow manufacturers in the

industry to dictate to their retailers both the type and the location of their customers.

On the other hand, the exclusivity features of the agreement enable the manufacturer

6 This distinction between the intermediary and an independent reseller was made because according

to S Petropoulos Parallel Imports, Free Riders and the Distribution of Motor Vehicles in the EEC: The

ECO System/Peugeot Case [1994] Consum L J 9, 16 the intermediary is perceived to be more than just a

parallel seller who stimulates intra-brand competition but also an economic operator who gives genuine

assistance to European consumers by facilitating access to goods in the Community.7 Report on the evaluation of Regulation (EC) No 1475/95 on the application of Article 85(3) of the

Treaty to certain categories of motor vehicle distribution and servicing agreements COM(2000) 743. Seealso M Monti Beyond the EUs Block Exemption (2000) No 2 Competition Policy Newsletter 1.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

3/22

VERTICAL AGREEMENTS AND CONCERTED PRACTICES [2003] EBLR 745

to split up the market and assign defined territories on an exclusive basis to its

distributors.

Various justifications for selective and exclusive distribution in the supply of new

cars have been brought forward, some of which were considered by the European

Court of Justice in Cabour.8 The main reason is to allow manufacturers to continueto influence the quality of their product by ensuring that a small concentrated number

of dealers have the degree of expertise and quality necessary to offer a high standard

of service for the consumer. Thus in the name of consumer welfare the manufacturer

usually agrees to supply only to dealers satisfying certain professional or technical

requirements9 while the approved dealers accept certain territorial restrictions and

undertake not to purchase or sell the contract goods from or to wholesalers or retailers

outside the official network. The Commission itself used consumer protection as a

justification for the restrictions that it allowed in the block exemption noting in thepreamble to Regulation 1475/95 that due to the nature of the product concerned a

number of restrictions of a selective and exclusive kind on distributors were indispen-

sable in order to allow some rationalization and as a result better motor vehicle

distribution and servicing (recital 4). In particular, it was felt that exclusion of whole-

salers not belonging to the distribution system of a manufacturer or importer from the

distribution of spare parts originating from the manufacturer should be exempted as

otherwise rapid availability of original spare parts, including those with low turnover,

would not be possible and this would then not be in the interest of consumers

(recital 6).

2. Selective Distribution Systems and Consumer Interests

This echoes what the Commission had said in the early 1970s when it justified the

granting of an exemption to the selective distribution systems of BMW, 10 SABA11

and Campari12 on grounds of consumer protection, holding that only by having

specially controlled outlets could a high standard of supply and service be guaranteed.

Yet it has always been debatable whether selective distribution systems in general

with the restricted competition that they generate are really providing benefits for

8 Case C-230/96 Cabour SA et Nord Distribution Automobile SA v Arnor SOCO SARL [1998] ECRI-2055.

9 For instance car manufacturers argue that the selectivity features and quality controls of the system

are necessary to ensure minimum and uniform standards that consumers expect from such reputedsuppliers and brands since consumers tend to identify the dealer with the supplier and to ensure that

consumers would be advised by retailers whose staff had the adequate expertise since cars are highly

complex products. Moreover if the right standard could not be maintained by the dealer, the suppliers

reputation would be damaged as the consumer would not be able to determine whether the fault in the car

is due to the dealers inaptitude to repair or a defect in the make.10 BMW[1975] OJ L29/1. In fact the first motor sector block exemption regulation, Regulation 123/

85 (n 1), was drawn along the lines set out in the Commission BMWexemption decision.11 SABA [1976] OJ L28/19.12 Campari [1978] OJ L70/69.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

4/22

746 EUGENE BUTTIGIEG

consumers that cannot be achieved in fully competitive markets as is claimed by

suppliers of such products.

Reich13 observes that in these cases one is confronted with the dilemma of defining

what is the true consumer interest in such circumstances. On the one hand, a selective

distribution system might benefit consumers because even if products are sold at a

higher price they get good service but on the other hand consumers may prefer that new

competitors that are not part of the selective distribution system be allowed to come

into the market and offer the product at a lower price. Good service is still guaranteed

since if they do not supply good service the consumer would desert them and at the

same time contract law on warranties and guarantees would ensure that suppliers abide

by quality standards. This argument is stronger now with theguarantees, product safety

and product liability directives inserting certain principles in all national contract laws.

Reich laments that we still do not know exactly what effects selective distributionsystems have on consumers. But he submits that the old theory that consumers inter-

ests are best served by industry (in the sense of industry knows whats right for the

consumer mentality) and a closely knit selective distribution system cannot be justi-

fied any longer. The consumer today has a wide choice of outlets and is protected by

civil law legislation. There is no reason why producers should be allowed to have a

selective distribution system in the name of consumer protection. The consumer will

be better served by competition backed up by strict rules on civil liability for warran-

ties, guarantees and product safety (now being further improved and given more bite

by the recent review of the product safety and product liability directives).

Thus BEUC had asked the Commission not to renew the exemption for SABA and

other producers of electronic devices on the grounds that the consumer interest could

be better served by other means and should certainly not justify a restriction ofcompetition.14 It feared that most producers would use the argument of consumer

protection to restrict competition in the entire market of electronic devices. Yet in

1983 the Commission renewed the exemption for a further 5 years. 15 It considered

that the distribution would bring immediate benefits for consumers in the form of

efficient after-sales service and availability of a wider range and faster delivery from

wholesalers and retailers. Moreover it felt that the benefits SABA receives in terms

of rationalization of its production and sales are likely to be passed on, in view of the

fierce competition in the consumer electronics business and the fact that all its whole-

salers and retailers can sell competing goods.

As for the Court, not only did it uphold the Commission decision on appeal but it

actually cleared the selective distribution agreement applying an almost rule of

reason analysis that however was even more complacent towards consumer interests

13 N Reich Community Consumer Law: Authoritative Power of the European Commission and the

Role of the Court of Justice with Regard to Consumer Law and Policy in T Bourgoignie (ed) EuropeanConsumer Law: Prospects for Integration of Consumer Law and Policy within the EC(Cabay-JezierskiLouvain-La-Neuve Belgium 1982) 217, 237.

14 Reich ibid.15 SABA (No 2) [1983] OJ L376/41. Reich (n 13) makes a plea to the Commission to at least hear

consumer associations first, if it is going to exempt a selective distribution system under Art 81(3), as it is

obliged to do by Regulation 17.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

5/22

VERTICAL AGREEMENTS AND CONCERTED PRACTICES [2003] EBLR 747

than the Commissions approach.16 It demanded only that the conditions of supply be

improved by the selective distribution system without requiring any proven benefit

to consumers for example in the form of better after-sales service, guarantees and so

forth.17 Van Houtte is critical of the Metro judgment:

It is not clear, however, how much weight the Court gives to consumer interests.

The Court merely notes in passing that a specialized distribution channel is in the

interest of consumers. The Courts insistence on intra-brand competition within

the distribution channel is presumably intended to benefit consumers, but it is

doubtful that consumers interests are served when products can be purchased

only from approved dealers, who will usually employ a more expensive selling

apparatus than would be the case in an openly competitive market. A plausible

argument can be made that at least some consumers would prefer a completely

competitive distribution system permitting them to buy products off the shelf at

the lowest possible prices. Regardless of whether insistence on intra-brand

competition adequately protects consumers it is clear from the Courts approval

of selective distribution systems that it gave more weight to the interests of manu-

facturers than to either consumers or excluded dealers.18

3. Motor Vehicle Group Exemptions Impact on Consumer Welfare

The motor vehicle group exemption attracted more widespread criticism because,

unlike the individual exemptions, it was granting Commission blessing to restricted

competition in an entire industry and thereby depriving consumers of the benefits that

full competition might have generated in the car industry. Criticism heightened when

after ten years experience under the first regulation19 had shown that the anticipated

benefits had not materialized while prices in certain States remained excessively high

the subsequent regulation20 renewed the block exemption for a further seven years

with minor changes. When the regulation was due to expire in September 2002 there

were renewed calls for its non-renewal with fresh arguments centering not only on

the high prices in States such as UK and Germany and the unjustified price differen-

tials between States21 but also on the effect that the system was having on consumer

16 Case 26/76 Metro SB-Gromrkte GmbH & Co KG v Commission (No 1) [1977] ECR 1875 andCase 75/84 Metro SB-Gromrkte GmbH & Co KG v Commission (No 2) [1986] ECR 3021.

17 N Reich Competition Law and the Consumer in L Gormley (ed) Current and Future Perspectiveson EC Competition Law (Kluwer London 1997) 127, 133 notes that here court was content with a mereimprovement in supply it was satisfied that consumers interests amounted simply to an increased choice

without giving any consideration to the need for a guarantee of high quality servicing.18 B Van Houtte A Standard of Reason in EEC Antitrust Law: Some Comments on the Application

of Parts 1 and 3 of Article 85 [1982] NJILB 497, 503.19 Commission Regulation 123/85 [1985] OJ L15/16.20 Commission Regulation 1475/95 [1995] OJ L145/25.21 The report on car prices published by the Commission in July 2002 shows that these substantial

price differentials have remained even after the advent of the euro Press Release IP/02/1109.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

6/22

748 EUGENE BUTTIGIEG

choice as it dampened parallel trading by reducing dealer capacity to compete on

price22 and limiting, through the sales targets and car allocation arrangements based

solely on sales made within the contract territory as sanctioned by the regulation, new

car availability for cross-border sales23 while the emergence of new alternative forms

of car retailing that are more convenient for consumers were being hampered by the

system that was propagated by the regulation.

In this block exemption the Commission tried to juggle between the interests of

consumers in having the possibility of sourcing new vehicles and after-sales services

throughout the common market and of acquiring quality products and after-sales

services at a competitive price and the contrasting interests of car manufacturers, car

dealers, independent resellers, independent repairers and spare-part producers.24 But

the end result was a block exemption that by allowing too many restrictions on the

dealers freedom weighed the scales against consumer interests, especially now that

22 The restrictions that the manufacturer was entitled by the block exemption to impose on dealers and

indeed the whole fabric of the selective and distribution system permitted by the block exemption placed

the dealer in a much weaker negotiating position vis--vis the supplier and this affected negatively

consumer interests as the dealer was unable to offer the competitive prices and choice that otherwise he

would have been able to offer. Without the restrictions authorized by the block exemption it is unlikely that

the suppliers would have been able to sustain the practice of effectively maintaining standard wholesale

prices for dealers by not giving them any volume discounts that would have exerted downward competi-

tive pressure on wholesale and retail prices. Moreover, brand exclusivity leads to dealerships being closely

identified with their suppliers to the extent that dealers behave more like agents for their supplier than

independent retailers. See the European Commissions Report on the evaluation of Regulation (EC) No1475/95 on the application of Article 85(3) of the Treaty to certain categories of motor vehicle distributionand servicing agreements COM(2000) 743 where it remarks that American dealers are generally in a

stronger position towards car manufacturers than their European counterparts and that in the US guaran-teeing the independence of dealers is seen as a means of protecting consumer choice and the UK

Competition Commissions Reporton the Supply of New Motor Cars within the UK(The Stationery Office2000) CM4660 which stressed that the inequality of power between manufacturers and dealers was

resulting in higher prices for UK private consumers by as much as 10 per cent. The Regulation allowed

the manufacturer to end dealer agreements even without cause with only two years notice and the diffi-

culty faced by dealers in such an eventuality of shifting to another brand because normally all sales

territories are already occupied by other dealers or even of recouping the money spent in substantial

investment to comply with the suppliers requirements was a strong incentive to dealers not to pursue a

sales policy which is disliked by their manufacturers. See M Monti Beyond the EUs Block Exemption

(2000) No 2 Competition Policy Newsletter 1, 3.23 In UK, according to the UK Competition Commissions report ibid, suppliers imposed targets at an

unreasonably high level that is hard to achieve and that did not include cars obtained by the dealer from

elsewhere in the EU. This prevented dealers from obtaining cars from other dealers outside UK and selling

them at a cheaper price to some consumers or spreading the savings over all customers to offer reductions

on all cars because they feared that then they would fail to meet the sales target and this is a ground fortermination of their contract.

24 Two of the stated aims of this regulation were directly concerned with consumer interests. First, the

regulation according to recitals 4, 7 and 30 of Regulation 1475/95 (and previously recitals 4 and 25 of

Regulation 123/85) was designed to ensure that motor vehicle distribution and servicing take place in an

efficient way to the benefit of consumers with effective competition existing between manufacturers

distribution systems and to a certain extent within each system. Secondly, the regulation according to

recital 26 was intended to further increase the consumers choice in accordance with the principles of the

internal market by creating an environment that improves the possibilities for inter- and intra-brand

competition and for parallel imports. In order to achieve this second aim the regulation had introduced the

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

7/22

VERTICAL AGREEMENTS AND CONCERTED PRACTICES [2003] EBLR 749

new forms of retailing and advanced car technology have negated the rationale

behind certain restrictions.25

The Regulation allowed manufacturers to appoint only one dealer for a geograph-

ically limited territory on which the dealer had to concentrate his marketing efforts

and endeavour to sell contract products in accordance with the sales targets agreed

with the manufacturer.26 Therefore, dealers were not allowed to open sales outlets or

to appoint sub-dealers or sales agents outside their contract territory. Moreover, the

practice common amongst nearly all car manufacturers of prohibiting their dealers

25 The block exemption allowed exclusivity and selectivity on the assumption that there is a degree of

inter-brand competition between the manufacturers of different brands and to a lesser extent even intra-

brand competition between the different dealers of the same brand with the objective of the block exemp-

tion (recital 30) being to ensure that European consumers take an equitable share in the benefit from the

operation of this competition. But in reality both inter-brand and intra-brand competition were rather

subdued so that the regulation by following a wrong assumption was, according to the Commissions own

report (n 22), leading to lesser competition in the car industry. In particular in reality dealers leeway to set

prices freely is severely limited due to the margin system operated by car manufacturers while they are

generally unable to compete effectively against the manufacturer for the latters reserved customers. On

the other hand, inter-brand competition is muted because real multi-brand arrangements (in the sense thatthe different brands do not belong to the same manufacturer) though allowed even under the previous

regulation are very rare in Europe, brand loyalty is very high among consumers and there is limited price

competition between large and smaller car manufacturers. See also comments by Jim Murray of BEUC at

the February 2001 hearing on the European Commission report claiming that the situation was actually

worse than depicted in the Commission report with very little real intra-brand or inter-brand competition

and that the block exemption is a major factor in facilitating unreasonable, unjustified and unnecessary

restrictions on competition .26 According to the European Commission most manufacturers took up this possibility its report

(n 22) noted that as a result of the combination of selectivity and exclusivity features in these vertical

agreements, while car manufacturers were entitled to impose high quality criteria on their dealers they

were not obliged to supply any new potential dealer who meets these criteria. The UK Competition

Commission claimed in its report (n 22) that though the sales targets were supposed to be agreed to

between the manufacturer and the dealer in line with the block exemption they are usually set by the

supplier unilaterally and by setting a target for every model the supplier could effectively force the dealerto supply every range. So though full-line forcing was not specifically exempted by the block exemption,

dealers due to the fear of termination of their agreement and because the selectivity and exclusivity

features of the system made them dependent upon the supplier to sell that make they normally accepted

the sales targets set by the supplier and this effectively forced them to sell the full range of models. This

in turn prevented some dealers from specializing in models that sell well with lower costs and lower

prices. So the features of this system were giving the ability to the suppliers to impose their will on

dealers and set targets for each model in a range with the adverse effect of raising prices for consumers

while full-line forcing was depriving consumers of a wider choice of type of retail outlets from where to

buy their cars.

following rules: the dealers remuneration may not depend on the final destination of a vehicle; dealers

may also actively promote the final sale of new vehicles outside their contract territory by advertising,

providedit is not personalized advertising; manufacturers have to impose on dealers an obligation to carryout repair and maintenance work also on vehicles sold by another dealer within the distribution network.

It was also assumed that by strengthening the dealers independence from manufacturers and thereby

increasing the dealers competitiveness and by protecting competition in the after-sales service market

both in relation to spare-part manufacturers and independent repairers, consumers would benefit

indirectly.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

8/22

750 EUGENE BUTTIGIEG

from selling actively by means of personalized advertising within the territory of any

other dealer was allowed. Restrictions on an active sales policy by car dealers outside

their contract territories were exempted on the grounds that these are indispensable

to ensure more intensive distribution and servicing efforts, better knowledge of the

market through closer consumer contact and a more demand oriented supply. In

effect, manufacturers were therefore allowed to divide up the market into exclusive

sales territories and to hamper consumers from purchasing especially across borders

new cars from resellers outside the manufacturers distribution network through a

ban on active sales by authorized dealers to independent resellers.27

Although consumers were entitled to purchase a new vehicle from authorised

dealers through an intermediary acting on their behalf (as an exception to the

embargo on active sales to independent resellers) the Regulation allowed manufac-

turers to make this subject to the rule that the distributors sales to intermediaries

must not make up more than 10 per cent of the distributors overall sales and that the

intermediary must have a clear mandate from the consumer to act on his behalf. 28

Thus in the final analysis for consumers there was no real alternative source of supply

for purchasing motor vehicles other than via the dealer networks.

27 Unlimited territorial protection however was not condoned as this was deemed to exclude the Euro-

pean consumers freedom to buy anywhere in the common market see recital 12. Therefore, dealers had

to be allowed to meet demand from final consumers in other areas of the common market and could not

be prevented from advertising in media which covered a wider area than their contract territory. In order

to ensure that consumers could exercise their right to purchase vehicles from anywhere in the common

market, dealers had inter alia the right to order from the manufacturer corresponding motor vehicles (this

is the so-called availability clause) vehicles similar to the ones distributed by the dealer but with

different technical specifications such as right-hand drive. On the other hand, dealers did not have totalexclusivity within their territory because most manufacturers do not give their dealers the exclusive right

to supply new vehicles to all consumers in the dealers territory they retain the right to sell new vehicles

to certain categories of consumers, so-called reserved consumers or customers in competition with their

dealers.28 The Notice accompanying Regulation 123/85 [1985] OJ C17/4 explained that refusal to supply is

permitted should the consumer or intermediary be unable to show documentary evidence that the interme-

diary is acting on behalf and on account of the consumer. While it has been argued that by institutionalising

the agency system the Regulation has invited abuse by bogus mandate-holders, this Notice was also the

centre of controversy in the Ecosystem case ([1992] OJ L66/1, on appeal [1993] ECR II-0493 and [1994]ECR I-277) where it was alleged that it appeared to contradict Art 3(11) of the Regulation. The Ecosystemcase concerned a French company that offered its services to French consumers to purchase a car on their

behalf in Belgium at a lower price than that charged by French distributors, prices of Peugeot cars being

substantially higher in France than in Belgium. Peugeot tried to stop Ecosystem from continuing to offer

such services by sending a circular to its distributors and resellers in France, Belgium and Luxembourg

asking them not to accept orders from Ecosystem nor to supply it with any new cars. The Commission foundthat this circular violated Art 81(1) and withdrew the exemption granted by the then Regulation 123/85 to

the standard distributorship agreement for Peugeot cars in Belgium and Luxembourg. This Regulation (Art

3(11)) already protected the activities of intermediaries acting specifically on behalf of final consumers and

duly authorized in writing by them. However, the Notice, referred to above, clarified that undertakings that

pursued an activity equivalent to resale would not be protected so that authorized distributors would be

entitled to refuse to sell vehicles to such third parties. This seemed to conflict with Art 3(11) of the Regula-

tion as it implied that even duly authorized intermediaries holding an express mandate from finalconsumers

could be refused delivery if de facto they pursue an activity equivalent to resale. Thus Peugeot challenged

this decision before the Court of First Instance on the ground that although Eco System was legally an agent

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

9/22

VERTICAL AGREEMENTS AND CONCERTED PRACTICES [2003] EBLR 751

By permitting exclusive and selective distribution systems, considering that all

manufacturers used such or similar agreements throughout the Community, the

Regulation allowed a cumulative anti-competitive effect to be generated by the

resulting network of agreements. On the one hand, through their single branding

clauses these agreements foreclosed or hampered market access for new manufac-

turers so that manufacturers might not have found distributors for their products

because all of them were bound to their existing supplier by an exclusivity clause. On

the other hand, the selectivity features of the agreements could likewise have had a

negative anti-competitive effect on distributors since EU-wide quantitative selection

coupled with territorial exclusivity of all dealers might have resulted in new distrib-

utors being unable to find a manufacturer willing to sell new cars to them.

An argument brought by manufacturers to justify exclusivity apart from the usual

enhancing of inter-brand competition concept is that it ensures national coverage of

the suppliers network as without allocated territories while the more populous areas

would be dominated by a few dealers and the weak ones ousted (due to fierce compe-

tition leading to closures), the less populated areas would not be adequately catered

for as dealers would concentrate on where demand is high. But this argument ignores

the fact that the rural areas could still be catered for by outlets that might take

different forms than those in urban areas (eg cooperatives or dealer groups) while as

regards the urban areas, that there would be a degree of dealer openings and closures

is the way a healthy market operates lack of closures due to allocated territories is

a market operating in an unnatural manner.

Moreover, this system of exclusive territories tends to protect inefficient dealers

efficiency can best be ensured through the discipline of market forces. Furthermore,

the granting of exclusive territories and the associated prohibition on the use of

personalized advertising outside the territory represents both a restriction on entry

and a major restriction on dealers ability to grow and hence a further disincentive for

efficient dealers to displace the inefficient.

of the consumer, in reality it pursued an activity equivalent to resale within the terms of this Notice. But the

CFIsaw no conflict between theRegulation andthe Notice. Nevertheless to clarify matters theCommission

within a fortnight of its decision adopted a specific notice on intermediaries Clarification of the Activities

of Motor Vehicle Intermediaries [1991] OJ C329/20 to further clarify the circumstances where they can

intervene on behalf of consumers setting out various criteria that distinguish intermediaries from mere

resellers. See S Petropoulos Parallel Imports, Free Riders and the Distribution of Motor Vehicles in the

EEC: The ECO System/Peugeot Case [1994] Consum L J 9. In particular the Notice placed various restric-

tions on intermediaries, some of which hindered them from giving an efficient service by limiting their

scope to organize their businesses freely and in the most efficient way. Eg, intermediaries had to avoid

carrying out their operations using a common name or sign, were prohibited from using an outlet within the

premises of a supermarket where the principal activities of the supermarket are carried out as well as from

receiving discounts different from those which are customary on the market of the country in which the car

is purchased. As a result of these restrictions, an intermediary was unable to get better deals for his

customers by grouping orders together and thereby getting higher rebates from a dealer who would save

advertising costs because of such group orders. Thus these rules governing the activities of intermediaries

made it difficult for them to become an easy and efficient channel for buyers who want to take advantage

of the pricedifferentials in the single market and hindered intermediaries from growing sufficiently to force

manufacturers to reduce the price differentials in Europe.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

10/22

752 EUGENE BUTTIGIEG

The usual free rider argument was brought by car manufacturers to justify the

selectivity and exclusivity elements of their distribution network. However, the free

rider argument does not take into account that not all consumers need the expert

advice of authorized dealers. Consumers are increasingly making use of specialist

magazines and the Internet as alternative source of information so that when they

visit the dealer they would already have decided on the make and model. In such

cases through this system authorized by the block exemption consumers were being

deprived of lower prices as they were constrained to pay for a service that they do

not need (prices reflect the cost of such services). Allowing alternative retail outlets

for new cars would mean that such category of consumers would be able to buy a

car at a cheaper price by forfeiting the service of expert advice. Indeed this would

be consonant with the principle currently underlying EC consumer policy that its

role is to ensure that the consumer is allowed to make his own fully informedchoices rather than to impose on him the choice that society thinks is best for the

consumer.

Likewise the practice of requiring dealers to achieve specified minimum standards

relating to various aspects of their business as endorsed by the block exemption

prevented some dealers from setting up and operating businesses with lower costs

and hence lower prices. This prevented the authorized dealers from adopting more

modern, efficient and cost effective forms of retailing that enhance intra-brand

competition, depriving consumers of lower prices and better delivery times, innova-

tive forms of car retailing more in line with consumer preferences and greater choice

of retailer from whom to purchase their new cars.29

Moreover, the combination of selectivity and exclusivity elements in the distribu-

tion system together with the strict restrictions on intermediaries meant that otheralternative forms of car distribution outside the manufacturers dealer networkthatarguably provide consumers not only with a more convenient form of retailing and a

wider choice but possibly lower prices due to lower distribution and specialized

29 According to the Regulation, a dealer could use all existing means to promote the sales of new cars

provided that he observed the minimum standards laid down by the manufacturer relating to advertising

and did not personally contact potential customers located outsidehis contract territory such as for instance

via e-mail otherwise the promotion of new cars by dealers through the Internet could not be prohibited,

even if the general advertising or promotion on the Internet reached customers outside the advertisers

territory (this is considered as passive sales by the Guidelines on Vertical Restraints). The difficulties arose

however when the block exemption was applied to brokerage or agency arrangements between dealers and

Internet operators. The Regulation hampered arrangements by virtue of which Internet operators might

operate as brokers or agents acting on behalf of the dealers. Apart from being inappropriate for the use of

Internet as this removes geographical barriers and territorial exclusivity, these rules had actually been usedby car manufacturers to impede the activity of Internet operators acting on behalf of a given dealer in the

exclusive territories of other dealers. See the European Commissions report (n 22) point 406 and Monti

(n 22) 7. The Regulation also excluded Internet operators from qualifying as dealers as they would not

fulfil the traditional criteria for the selection of new dealers used by all car manufacturers and endorsed by

the Regulation. Besides, the Regulation only exempted distribution agreements for new cars if the distrib-

utor apart fromselling newcars also providedafter-sales servicing something which the Internet operator

is not in a position to provide. Nor did the Regulation entitle dealers to sell to Internet operators who would

then resell directly to consumers as it exempted the prohibition of the sale of new cars by dealers to inde-

pendent resellers. Even acting as intermediaries might have presented problems for Internet operators

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

11/22

VERTICAL AGREEMENTS AND CONCERTED PRACTICES [2003] EBLR 753

service costs such as Internet retailing,30 supermarkets, vertically integrated sales

companies or dealers specialized in the sale of a specific type of car were inhibited

because the supplier was allowed to refuse to supply such alternative outlets with

stock and to prevent his dealers from selling to them. 31

Multi-branding or multi-marketing (ie, the sale of competing manufacturers

vehicles) was also to a large extent excluded by the Regulation and most car dealers

in fact only sell cars belonging to one manufacturer, even if sold under different

brands. Selling a make produced by a different manufacturer would only have been

allowed in the rare instance where the seller is a separate legal entity run by separate

management and where the sale is made in separate premises and in a manner which

avoids confusion between makes.32 These restrictions laid down in the Regulation

regarding separation of premises and management proved to be unattractive to

30 Virtual dealers would promote new cars solely or mainly through the Internet and deliver them tocustomers homes. Since customers might rarely visit the premises of such dealers, the premises could be

provided more cost-effectively, in lower-cost areas, than existing showrooms. It is also envisaged that as

greater use is made of Internet in car distribution in Europe, parallel cross-border trade would flourish

resulting in a reduction in price differentials between Member States and an increase in competition in the

after-market between the official networks and independent undertakings.31 During the February 2001 hearing on the European Commission report the Comitato Consumatori

Altroconsumo argued that it should be the free market and not a regulation that determines the form of

distribution that retailers can best develop to meet demand. This would enable consumers to gain from the

big differences in price between Member States. This would mean that there would not be just one form

of distribution for the whole of Europe but the market would develop various alternative forms of distri-

bution determined by market forces and differing according to the type of car and geographically or

regionally tailored to the local demand. See .32 The Commission reported (Commission report n 22) that in practice true multi-brand dealerships

where dealers sell brands from different manufacturers not belonging to the same group, are rare as inmost cases where a dealer sells a second brand this brand belongs to the same manufacturer. Moreover, a

good percentage of all main dealers sell only one brand. In UK, according to the UK Competition

Commissions report (n 22), most dealer groups operate separate franchises for severals uppliers and some

operate multiple franchises from distinct but adjacent premises. In the US multi-branding dealerships are

more common as US rules on multi-marketing are less strict but the European Commission (report n 22)

shows that even here the dealers generally take complementary franchises rather than franchises for prod-

ucts directly competing with the products they are distributing. Only a very small percentage of US

dealers would sell competing American makes most would sell European or Asian makes with the

American make.

because of the above mentioned requirement of a written and signed mandate in the Regulation. This

requirement raises practical problems for transactions carried out via the Internet where the authorization

may consist of an electronic message. Likewise sales via supermarkets generally suffered from the same

difficulties as Internet operators when they act as brokers or agents of a dealer, as dealers themselves or

as independent resellers of cars. Acting as intermediaries for final consumers could also present problems

for supermarkets. Ironically, the restrictions imposed in the notice on intermediaries (n 28) were intended

to protect consumers but they might discourage supermarkets to offer such services to the consumer.

According to the notice, supermarkets had to take all measures to avoid confusion in the minds of

consumers as regards on the one hand their activities as an intermediary and on the other their normal

commercial activities as a supermarket selling goods.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

12/22

754 EUGENE BUTTIGIEG

dealers in financial terms so that real multi-marketing was rare. 33 This prohibition

of multi-marketing as well as of the sale of spare parts that do not match the quality

of spare parts of the contract range34 was generally allowed by the Regulation

because this was deemed to contribute to the concentration of the dealers on the

contract products and thus ensure appropriate distribution and servicing of vehicles.

But multi-marketing is advantageous to final consumers because it provides a

wider range of products and/or brands at one single site obviating the need to shop

around to compare different models. Though adjacent dealerships as permitted by

Regulation 1475/95 would still have reduced search costs for the consumer, they did

not allow the possibility of receiving directly comparative advice from sales staff on

the merits of cars of different brands. Thus the perceived benefits for consumers from

multi-marketing intended by the Regulation never materialized.

Suppliers argued that brand exclusivity was needed because cars are complex,expensive and potentially dangerous products and so sales staff must be experts in

the particular brand but this argument is unpersuasive since surveys show that a good

proportion of consumers would wish to purchase cars from multiple brands outlets or

supermarkets and because they increasingly obtain their information from sources

other than the expert salesman they do not seek his expert advice to purchase a new

car.

It has also been argued that consumers do not expect unbiased advice from sales

staff in an outlet which is exclusive to one brand, whereas they might in a multi-brand

outlet, with a consequent risk of their being misled if the outlet concerned pushes the

models that brings them the highest commission. However, this difference between

the two situations should not be exaggerated as even sales staff in an exclusive outlet

may be motivated to push one model variant ahead of others, if for example, the deal-ership has a particular desire to sell that variant in order to meet a sales target and

hence earn bonus.

A further important consideration is that since with multi-marketing dealers are

able to choose which products to offer, suppliers would have to compete for their

business. This competition at wholesale level for dealers shelf-space would bring

downward pressure on wholesale prices and increased pressure on suppliers to

improve product quality and overall value for money. It is also argued that brand

exclusivity has a negative effect on innovation as it makes it impossible for suppliers

with a small share of total sales and for new entrants to have their products displayed

and sold by existing outlets. Moreover, brand exclusivity greatly restricts dealers

freedom to develop multi-franchise outlets and reduces the choice of type of retailer

from which customers may buy new cars and reduces innovation in car retailing.

33 The restrictions did not allow dealers to take advantage of the economies of scale which multi-

marketing would normally allow as regards overheads. Dealers were also unable to develop buying skills

and use them to select the products that offer the best value for money.34 As regards spare parts that match the quality of contract goods, the dealers had to be allowed to

source such parts from other suppliers and to use them for the repair of vehicles unless this is done within

the warranty period or in the context of a recall operation.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

13/22

VERTICAL AGREEMENTS AND CONCERTED PRACTICES [2003] EBLR 755

Car manufacturers were required by the Regulation to impose on dealers the obli-

gation to provide after-sales services. This tied two different types of businesses the

sale of new cars to the after-sales services activities. However the Commission

regarded the linking of servicing and distribution of new vehicles as more efficient

than a separation of both activities, particularly as the distributor must give new vehi-

cles a technical inspection according to the manufacturers specifications before their

delivery to final consumers (recital 4). It was claimed that there is a natural link

between sales and servicing based on technical35 and economic36 considerations.

Moreover, it was argued that the link guarantees safety and product reliability for

consumers as the dealer himself would be required to carry out the pre-sale inspection

of the car being sold and ensures appropriate servicing thereafter.

However, today this link is not proved empirically as a number of car manufac-

turers have in fact appointed separate service outlets so as their dealers may

concentrate solely on the sale of new cars while some dealers themselves run service

centres that are physically separated from their sales outlets. Indeed, it is claimed that

the technical and economic considerations that hitherto justified this link no longer

apply nowadays.37 And in any case there are alternative ways by which the necessary

result can be achieved without having the tying; for instance, by a sales only retailer

subcontracting local garages for this purpose and some of the pre-delivery inspec-

tions being done by the supplier centrally while for warranty related services the

supplier could approve a number of garages as suitable to carry out warranty and

product recall work.

Moreover, though it is argued that such a tying of sales and servicing is advanta-

geous to all manufacturers, importers, dealers and consumers the majority of

consumer associations actually hold the view that such a link is not indispensable and

35 Such as that the new car requires a pre-delivery inspection according to the manufacturers speci-

fications which can only be carried out by the dealer who delivers the car to the final consumer. Moreover

the link was also considered important for the purposes of the manufacturers warranty, recall campaigns

and vehicle repair and maintenance.36 Profitability from the sale of new cars is low and so dealers need to supplement their income by

revenue from the more lucrative and viable business of after-sales services.37 Pre-delivery inspections are no longer necessary and where required are already carried out with

the car manufacturers consent by undertakings that do not belong to its distribution network. Moreover,

since the car manufacturer has no control over the repair and maintenance of a car once sold, there is

nothing to stop consumers from seeking other network dealers or service outlets than the one from whom

the car was bought or even independent repairers who are all technically equipped to carry out such after-

sales services, without this having an effect on the warranty this therefore defeats the argument that

technical reasons militate in favour of the link. As for economic considerations, the Commission in itsreport questions whether the reason for the low profitability of new car selling is really due to lack of

incentive on the part of dealers to rationalize their sales departments to reduce costs because they have the

possibility of offsetting this activity with profits from the after-sales department. It could therefore well be

that economically the sales activity could in reality be a stand-alone activity and remain viable as in such

a scenario the dealer would make it adequately profitable by reducing costs, once he can no longer rely on

the after-sales activity. Moreover, in order to be able to honour the warranty and offer repair services for

faulty vehicles free of charge to their customers it is not necessary for manufacturers to tie selling of cars

to after-sales services as manufacturers can, as some do, make arrangements with reliable service outlet

networks to carry out the repair services and then be reimbursed by the manufacturer.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

14/22

756 EUGENE BUTTIGIEG

that a split would be advantageous for consumers with some associations criticizing

the cross-subsidization between sale and servicing activities.38

Furthermore, while pre-sale inspection is increasingly not necessary nowadays,

high consumer mobility today results in cars being serviced not by the dealer who

sold the car but by another network dealer or service outlet. Since all these undertak-

ings operate on the basis of the standards set by the manufacturer, the consumer is

guaranteed safety and product reliability without the need for the dealer to be obliged

to offer the after-sales services as well. So the behaviour of consumers puts in doubt

the existence of a natural link between these two activities. This conclusion is further

strengthened by the findings in the European Commission report that owners of older

cars that naturally are in need of more repair tend to seek independent repairers rather

than the dealer from whom the car was bought to preserve the value and safety of the

car.

Furthermore, a study carried out by Autopolis concluded that although some

consumers want their car serviced by the same firm that sold them the vehicle, the

sales-service link was in the main not driven by a genuine market need, but was rather

forced by car manufacturers operating within the Regulation.39 The imposed link

curtailed the activities of many types of undertakings engaged in car repair outside

the network. Autopolis claims that without this imposition there might have been

more opportunity for innovative offerings from a variety of operators in both the fran-

chise and non-franchise sectors, in response to consumer-driven market

requirements. It also observed that lack of standardisation in electronic diagnostic

equipment might also be used by the car manufacturers to shut independent repairers

out of a large part of the repair and servicing market.

It was also argued by suppliers that this tying of sales with servicing was necessary

because a dealer business combining both sales and services was inherently more

stable than one providing sales only because inter alia of the cyclical nature of the

new car market. But this means that once there exist these reasons, even without

tying, dealers would do both anyway they would still continue to operate an inte-

grated business even if they were not required to do so. On the other hand, the

compulsory element in this tying prevented the emergence of outlets specializing in

either new car sales or supplier-approved servicing but not both. Consumers were

thus left without a choice of type of outlet while the benefits of specialization in both

were dubious.

With a view to enhancing consumer choice in relation to the range and price of

spare parts (non-originals of matching quality are about 30 per cent cheaper

according to the European Commission report) the regulation protected the freedomof dealers to purchase spare parts of matching quality from sources other than the car

38 Spare-part producers were also critical as they felt that this tying was strengthening the dominance

of manufacturers and their dealer networks over spare-part suppliers as all parts were sourced through car

manufacturers thereby cutting out spare-part producers and preventing them from having direct access to

the dealer networks.39 The Natural Link between Sales and Service November 2000

.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

15/22

VERTICAL AGREEMENTS AND CONCERTED PRACTICES [2003] EBLR 757

manufacturer with whom they have a contractual relationship for the repair and main-

tenance of cars. On the other hand, in order to protect another consumer consideration

his safety this freedom was limited by the requirement that the parts must corre-

spond in quality to those produced and distributed by the car manufacturer who was

entitled to verify the quality of these parts and to require dealers to use original parts

only for work under guarantee, free servicing and vehicle-recall work. Moreover,

there was a general obligation imposed upon dealers to inform customers on the use

of non-original spare parts a rare case of a competition law measure imposing an

information obligation in favour of consumers. Usually such information obligations

are contained in consumer protection measures that in tandem with competition law

guarantee fair trading in the market for the consumer by redressing market failures

and information deficiency that inhibit proper economic self-determination.

However, the European Commission report showed that in reality dealers due to

discounts and other incentives or indirect coercive tactics by car manufacturers

generally preferred to use original spare-parts so that consumers were not getting the

benefit of choice and lower prices.40 So the objective of the Regulation was not being

fully achieved.

Another weakness identified by the European Commission report was the weak

consumer choice as regards independent repairers because due to various practical,

economic, financial and technical reasons most independent repairers in contrast to

the dealers still did not have full access to technical information raising even safety

and environmental concerns.

Another factor that the Commission identified as weakening consumer welfare in

relation to after-sales services was that most manufacturers have inserted a clause

that makes the manufacturers warranty conditional on the consumers having theircars serviced solely by the network dealers or service outlets so that the warranty is

forfeited if the car is repaired or maintained by an independent repairer. This tying

clause which can have a very negative effect on competition and consumer welfare

especially where there is a low ratio between the duration of the warranty and the

lifetime of the vehicle was not prohibited by the Regulation.

40 Large discounts granted by car manufacturers to their dealers for the purchase of original parts; the

practice of most car manufacturers to recommend (though not impose) to their network the range and

number of spare parts that a dealer should hold for optimum efficiency or include annual target sales; fear

of losing end-of-year bonuses granted on the basis of the annual original spare-part turnover; fear that

excessive use of non-original parts will lead to the termination of their contract; the practice by most car

manufacturers (though this was blacklisted by the Regulation) of requiring their component suppliers to

sell components and spare parts for a given model only to them and not directly to its dealers. Moreover,it is alleged that though Regulation 1475/95 (recital 8) contained a presumption that parts coming from the

same source of production were identical in quality to original spare parts and required the spare-part

manufacturer to confirm that these parts correspond to those supplied to the car manufacturer, some car

manufacturers still raised doubts about the quality of such parts. Furthermore, in some cases car manufac-

turers followed a policy of hindering car part producers from placing their trademark or logo in a visible

manner on these parts in order to avoid transparency as to the real origin of such parts. Thus consumers

would be unable to make a real choice between an original part and a part coming from the same part

producer but distributed under his brand name. Such a practice would of course be a violation of the

Regulation.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

16/22

758 EUGENE BUTTIGIEG

Yet another feature of Regulation 1475/95 that was criticized was that the standard

practice of suppliers setting list prices that in fact amount to recommended retail

prices (RRP) was not prohibited by the block exemption that only blacklisted a prac-

tice or requirement that directly or indirectly restricted the dealers freedom to

determine prices and discounts (Art 6(6)). Suppliers have argued that this practice is

actually beneficial to consumers as it provides a benchmark price with which dealers

prices could be compared. Yet as is shown by the UK Competition Commissions

report41 while this is true in certain retail sectors and circumstances, the retailing of

new cars differs from other retail sectors. Where retailers frequently offer different

prices and these are clearly advertised, whether in the media or in the retail outlet, the

posting of an RRP or the knowledge of it provides the consumer with useful informa-

tion for evaluating an offer and comparing it with those of other retail outlets. But in

the new car retail sector the price is open to a degree of negotiation and dealers gener-ally display the RRP itself or an on-the-road price based on it rather than the price

at which they are prepared to sell. The real transaction price that is available may be

significantly different from the RRP but is not easy to establish. Not only do

consumers differ in their knowledge and expectations of the discounts that can be

negotiated, they cannot tell whether a particular offer is a good deal or not. In these

circumstances, the RRP is likely to have a misleading effect, at least for some

consumers. This is the more likely in that there are other features of the package for

the consumer the wide availability of financial benefits, equipment extras and

negotiated trade-in terms on which the consumers attention may be focused, rather

than on the RRP. So in the circumstances of the car industry the suppliers practice

of setting RRPs reduces transparency for the consumer (in some countries this lack

of price transparency is further exacerbated by the practice of bundling of financialbenefits such as cheap finance and insurance with the car price) and increases the

average price paid.

A further effect that arises from the wider lack of transparency, in which RRPs are

a central element, is a reduction in the impact on transaction price setting of those

consumers who shop around, since dealers are able to discriminate between

purchasers and offer the more active consumer a better price without feeling any

pressure to offer the same price to other consumers. Without RRPs dealers would

play a more important role in price-setting by publicizing their own price lists.

Though these prices would also be negotiable as this is the custom and practice in the

market, this situation would increase the transparency of dealers price offers. Shop-

ping around by consumers would then lead to downward pressure on dealers

published prices. So again this practice that was allowed under the block exemption

was also leading to prices for consumers higher than they would otherwise be.

41 Report on the Supply of New Motor Cars within the UK(The Stationery Office 2000) CM4660.

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

17/22

VERTICAL AGREEMENTS AND CONCERTED PRACTICES [2003] EBLR 759

4. The NewRegulation on Vertical Agreements and Concerted Practices in the

Motor Vehicle Sector

The new block exemption,42 that, while no longer exempting a combinedselectiveand exclusive distribution system nevertheless allows the manufacturereither toimpose a selective (minus the location clause) or an exclusive distribution systemon its dealers provided market share thresholds are not exceeded, seeks to redress

most of these shortcomings. For instance, the inequality of power that existed

between manufacturers and dealers43 has now been remedied in the new regulation

through more safeguards; supply quotas and sales targets must now be set for the

entire common market rather than for the small allocated territory as provided under

the previous regulation;44 the new regulation allows the development of innovative

distribution formats so that official dealers may now develop internet sales or enterinto partnership with referral sites to promote their business and with all kinds of

intermediaries having orders from final customers including supermarkets; the new

regulation provides for improved access to technical information for independent

repairers; it injects more competition into the market by now ensuring that inde-

pendent resellers and intermediaries are not hindered from acquiring new cars

unlimitedly by inter alia also removing the 10 per cent rule and all the other restric-

tions prescribed in the related Notices though it still maintains a distinction between

independent resellers and intermediaries by retaining the mandate requirement in

respect of the latter;45 multi-branding is made easier as different makes can be exhib-

ited in the same showroom but in different sales areas while the location clause in

selective distribution systems (this clause allows a manufacturer to request that a

distributor only operates from a certain place of establishment usually in conjunctionwith an undertaking not to allow any other distributor to open a showroom in that

territory) is now prohibited; the tying of the new car selling business to after sales

services activities has been removed while the new regulation seeks to ensure that the

consumer does get the full benefit of free competition in the spare parts market by

guaranteeing better direct access from spare part producers to authorized repairers

and greater consumer choice between original spare parts supplied by the car manu-

facturer, original spare parts supplied by the spare part manufacturer and matching

quality spare parts supplied by another spare part producer.

Although the new regulation retains the much criticized non-prohibition of the

standard practice of suppliers setting list prices that in fact amount to recommended

retail prices (Art 6(6) in the previous regulation and Art 4(1)(a) in the new regulation

only blacklists a practice or requirement that directly or indirectly restricts the

dealers freedom to determine prices and discounts), since the regulation has

42 Commission Regulation 1400/2002 on the application of Art 81(3) of the Treaty to Categories of

Vertical Agreements and Concerted Practices in the Motor Vehicle Sector [2002] OJ L203/30 in force

since 1 October 2002.43 See n 22.44 See n 23.45 See n 28. These notices were abolished but the Regulation retains the mandate requirement see

explanatory brochure .

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

18/22

760 EUGENE BUTTIGIEG

removed the combination of selectivity and exclusivity elements from this distribu-

tion system, RRPs, as in any other distribution system, will now tend to provide more

benefits than harm to consumer interests. Certainly RRPs provide a single benchmark

price for each model variant and this would be very beneficial for consumers as it

reduces search costs. Moreover, some of the more vulnerable consumers might be

induced to pay higher prices than they otherwise would if RRPs were to be discon-

tinued. At the same time, RRPs would be much less likely to have an adverse effect

on transaction prices as retailers would now play a much more important role in the

advertising and setting of prices as they will no longer be subject to the suppliers

pressure that induced them to stick closely to the suppliers RRPs.

Not all features of the previous regulation impacted negatively on consumer inter-

ests in some respects the regulation did on balance result in consumer benefits. And

these features were retained in the new Regulation. In order to ensure the consumers

basic right to buy a motor vehicle and to have it maintained or repaired wherever

prices and conditions are most advantageous to him in the common market the Regu-

lation continues to provide that:

G A consumer is entitled to the normal product range that the dealer offers to his

incumbent customers. Moreover, this right is extended to vehicles which corre-

spond to vehicles distributed by a dealer but with the specifications marketed by

the manufacturer in the Member State where the consumer wants to register the

vehicle. This availability clause in the Regulation means that a British or Irish

consumer is entitled to buy a right-hand drive passenger car from a dealer in

mainland Europe and the manufacturer is obliged to supply such a dealer on

order with cars with such specifications that are sold in UK and Ireland and vice-versa. However, the dealer may of course be charged a supplement by the manu-

facturer in addition to the normal price, provided such supplement is objectively

justifiable on the basis of special distribution and administrative costs and differ-

ences in equipment and specification and not discriminatory (recital 20). Art 6

guards against abuse by empowering the Commission to withdraw the benefit of

the block exemption where objectively unjustified prices or conditions are

imposed for corresponding passenger cars. The latter scenarios impact directly

consumer interests and so the block exemption has an inbuilt mechanism to

diffuse situations where consumer interests are being affected negatively and in

fact the Commission in its report mentions one case where the car manufacturer

was found to be charging right-hand-drive supplements not based on objective

criteria and following the Commissions intervention it reduced the supplement

substantially.

G The consumers freedom to source a vehicle or after-sales services wherever it

is most advantageous is also protected from direct or indirect bilateral or unilat-

eral measures on the part of manufacturers or distributors such as longer delivery

times or refusal to carry out warranty work. Thus in order to facilitate cross-

border sales of new cars by consumers, the Regulation obliges manufacturers to

impose on their dealers the obligation to honour the warranty and to perform free

servicing and vehicle recall work even when the car has been bought from

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts

19/22

VERTICAL AGREEMENTS AND CONCERTED PRACTICES [2003] EBLR 761

another dealer in the country or outside the country (recital 17). This rule that

clearly guarantees and protects the freedom of consumers to purchase new cars

wherever in the European Union they find advantageous prices and conditions

has its origins in the earlier Commission decisions such as Zanussi.46

G The Commission attempts to guard consumers against price differentials in

Europe by retaining the right to withdraw the benefit of the block exemption

should prices differ substantially between Member States as an effect of any

particular vertical agreement falling within the scope of the Regulation. This

apart from when there results a lack of competition or where parallel trading is

hindered in addition to the automatic loss of exemption when the manufacturer,

supplier or another undertaking within the network directly or indirectly impedes

final consumers from buying a vehicle where they consider it to be most

advantageous.47

In addition the prohibition of the location clause in the new regulation means that

distributors from cheap countries can now open sales or delivery outlets in high

46 Zanussi SpA Guarantee [1978] OJ L322/26. The first time the Commission made it clear thatgeographical limitations on the terms of manufacturers guarantees or the way in which they were applied

could infringe Art 81(1) was in the context of an investigation into distribution of Constructas domestic

electrical appliances. At the Commissions insistence arrangements were made to ensure that purchasers

of products in other Member States would have the manufacturers guarantee honoured in Belgium or

Luxembourg if necessary ( IVth Report on Competition Policy (Commission 1974) point 109). Thisapproach has been endorsed by the Court. In Case 31/85 ETA Fabriques dbauches SA v DK InvestmentSA [1985] ECR 3933 the ECJ noted that it is important that the possibility of obtaining products by meansof parallel imports should not be restricted. As far as the guarantee scheme was concerned, it was essen-

tial for parallel imports to be fully covered by the manufacturers normal guarantee. A guarantee schemeunder which a supplier of goods restricts the guarantee to customers of his exclusive distributor places the

latter and the retailers to whom he sells in a privileged position as against parallel importers and distribu-

tors and must therefore be regarded as having the object or effect of restricting competition within the

meaning of Article 85(1) [81(1)] of the Treaty. The fact that the manufacturer tolerates the distribution

of his products through a network of parallel importers must be considered irrelevant, since the guarantee

scheme may have the object or effect of bringing about, to some extent, a partitioning of national markets.

Likewise in Case 86/82 Hasselblad (GB) Ltd v Commission [1984] ECR 883 Court held that there is aninfringement of Art 81(1) where a manufacturer undertakes with his exclusive distributor to grant a guar-

antee on his products to the consumer but withholds the benefit of this guarantee in respect of the products

purchased through parallel importers.47 Prior to July 2002, this protection against price differentials was not absolute since the Commission

declared in the Notice accompanying the original Regulation 123/85, [1985] OJ C17/4, that it will inves-

tigate price differentials only if certain given conditions subsisted. Indeed though price differentials

continue to pervade the car industry this withdrawal mechanism was never activated and the Commission

found in its report that although its latest car price reports showed price differentials have not becomesignificantly smaller but regularly exceed 20 per cent and could be as high as 65 per cent in some cases

(its 2000 report showed that some consumers in the UK pay up to 76 per cent more for certain brands

than their European counterparts) it had not investigated because the excessive difference in price was

mostly due to the high car taxes imposed by some countries. According to the Notice, the Commission

would not investigate price differentials that do not exceed 12 per cent, nor those that exceed that

percentage by less than 6 per cent over a period of one year. Neither would it investigate if only an insig-

nificant portion of motor vehicles is concerned or if taxes, charges or fees for a new vehicle amount to

more than 100 per cent of the net price or if the level of resale prices is subject to state measures for more

than one year. Moreover, the Commission would also take account of exchange rate fluctuations when

investigating price differentials. However at least the reports on car prices within the EU published every

-

8/7/2019 buttigieg spare parts