But Were Afraid to Ask Part II: Finding Order Amid … Birding molt 2003 part...642 BIRDING •...

Transcript of But Were Afraid to Ask Part II: Finding Order Amid … Birding molt 2003 part...642 BIRDING •...

B I R D I N G • D E C E M B E R 2 0 0 3640

Part 1 of this review (Birding,October 2003, pp. 490–496)

discussed examples of the seem-ingly endless variations possible inmolt strategies worldwide, relatingto when and where a bird molts.These variations come aboutthrough the interplay of several un-derlying factors that can be summa-rized as: 1) environment and food;2) breeding and size; and 3) migra-tion. In Part 2 we’ll look at howpatterns of molting can be identi-fied to reveal some semblance of or-der amid the apparent chaos. Thenwe’ll review real-life examples andcompare the Humphrey-Parkes sys-tem (which considers only thenumber of molts) with the life-yearsystem (which relates plumages anda bird’s appearance to seasons).

Molt TerminologyThe molt strategies of birds—dis-cussed in Part 1 of this article—areinextricably linked with other as-pects of their life histories, such asbreeding cycles, food supply, and, insome cases, migration cycles. Tradi-tional terminologies, originating inthe temperate regions of Europe orNorth America, have used termssuch as “breeding” or “nuptial”plumages, or “summer” and “win-ter” plumages. Humphrey andParkes (1959, 1963) pointed out,however, that for meaningful com-parisons to be made among species

worldwide, a system of nomencla-ture for molts and plumages shouldbe free from preconceptions relatedto other life-history phenomena.Consequently, their 1959 paper in-troduced a system of nomenclaturewhereby variations in the patternsof plumage succession may be de-scribed, compared, and contrastedamong different groups of birds byapplying the concept of homologyto the study of molts.

The defining criterion for homol-ogy is common ancestry: Sincemodern birds presumably share acommon ancestor, they should alsoshare a common molt strategy.(Analogy, by contrast, reflects con-vergence through adaptation. Forexample, human hands and batwings have homologous bonestructures, whereas bat wings andbird wings are analogous adapta-tions for flight.) In some cases, de-termining homologies can be prob-lematic, if not impossible (Mindelland Meyer 2001), but observationsand syntheses of broad patterns canproduce hypotheses regarding pre-sumed homology. The Humphrey-Parkes (H-P) system provides a ter-minology for such hypotheses andhas proved useful in comparativestudies of molt.

Although the H-P system is help-ful for comparative studies of molt,it is not necessarily the most help-ful for field birding. Still, to under-

U N D E R S T A N D I N G M O L T : P A R T I I

by Steve N. G. HowellPRBO Conservation Science

4990 Shoreline Highway

Stinson Beach CA 94970

All You Ever Wanted to Know About MoltBut Were Afraid to Ask

Part II: Finding Order Amid the Chaos

All You Ever Wanted to Know About MoltBut Were Afraid to Ask

Part II: Finding Order Amid the Chaos

All You Ever Wanted to Know About MoltBut Were Afraid to Ask

Part II: Finding Order Amid the Chaos

W W W . A M E R I C A N B I R D I N G . O R G 641

stand the basics of molt strategieswe should start with a review of theH-P system, incorporating somemodifications proposed recently byHowell et al. (2003) and also sum-marized by Sibley (2002). Remem-ber, though, that Nature does notfit neatly into boxes, so there willalways be exceptions that challengeany rules we try to apply. To focuson exceptions is understandable,but to look at broad patterns thatapply to the majority of speciesmay be more meaningful and alsohelps to identify where exceptionsreally lie.

The Humphrey-Parkes SystemThe H-P system is founded upon afew tenets, foremost among whichare the following: (1) Only moltsproduce plumages; that is, a birdcan have no more and no fewerplumages than it has molts. (2) Thecomplete (or near-complete) moltsof adults can be considered homol-ogous and thus comparable amongspecies. (3) Molts and plumages

should be named independently ofother phenomena in a bird’s life cy-cle, such as seasons or breeding sta-tus. And (4) molts are named forthe plumages they produce, not forthose they replace. The H-P systemwas developed with adult birds inmind, and for these birds it workswell. In essence, the H-P system isconcerned only with the bottomline of how many molts occur, i.e.,how many times a feather follicle isactivated; it does not worry aboutwhen or where the molts occur, orabout what the resultant plumageslook like.

The gist of the H-P system is thatthe complete (or near-complete)molt can be considered homologousamong all adult birds; otherplumages have evolved as additionsor responses to various types of se-lection. The H-P system uses theneutral term Basic Plumage for thispresumed homologous plumage,worn by all birds. This is actuallyquite an intuitive term: All birdshave a basic plumage; it’s that basic.

In fact, most birds worldwide haveonly basic plumages, and so theymolt from one basic plumage to an-other basic plumage each year (e.g.,penguins, hawks, hummingbirds,jays, and even many wood-war-blers). Hence, in these species, basicplumages encompass both the so-called “summer” and “winter”plumages or the “breeding” and“non-breeding” plumages.

The commonest variation on thisbasic pattern is the addition of an-other plumage into the adult cycle.The H-P system calls any secondplumage added into the basic cyclean Alternate Plumage—it alternateswith the basic plumage, and, often,it creates an alternate appearance.An alternate plumage is any secondplumage, regardless of when it is at-tained; often it is equated with“breeding plumage”, but this is anoversimplification that can be mis-leading. In a few cases, anotherplumage or plumages may be addedinto the basic cycle in addition toalternate plumage; the H-P system

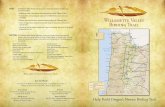

Fig. 1. Diagrammatic representation of underlying molt strategies that build upon the Simple Basic Strategy (SBS): the Complex Basic Strategy (CBS), Simple Alternate Strategy (SAS), andComplex Alternate Strategy (CAS). Juv: Juvenal Plumage (First Basic). F1: Formative Plumage. A1: First Alternate Plumage, etc. B2: Second Basic Plumage, etc. Molts are indicated symboli-cally as breaks between plumages and cycles, and the area below the dashed line represents flight feathers (which can be replaced in some F1 and A1 plumages). Note that a cycle extendsfrom the initiation of one prebasic molt to the initiation of the next, and that plumages (and molts) are consistently numbered in reference to the cycle in which they occur. In many CBSand CAS species, note that adult plumage is attained in the second plumage cycle; that is, B2 (and A2) plumage equals adult basic (and alternate) plumage. From Howell et al. 2003.

B I R D I N G • D E C E M B E R 2 0 0 3642

provides the term Sup-plemental Plumage forthese extra plumages,but they are suffi-ciently rare and poorlydocumented that weneedn’t worry aboutthem. Note that basic,alternate, and supple-mental refer toplumages, not tomolts. The molts bywhich these plumagesare attained are calledthe Prebasic Molt, thePrealternate Molt, andthe PresupplementalMolt, respectively, i.e.,the molts that precede,and produce, theseplumages.

Successive basic (and alternate)plumages, if they can be distin-guished by color or pattern (as inimmature gulls, for example), arecalled second basic, second alter-nate, third basic, and so on, untiladult plumage is attained. Oneother H-P term you should beaware of is Definitive, which refersto any plumage (basic or alternate)that no longer changes in appear-ance with age. Hence, definitiveplumage usually equates with whatis commonly termed “adult”plumage.

The original H-P system consid-ered the first postjuvenal plumageas the so-called “first basicplumage”, and this marked the startof their system for naming basicplumages. The frequent similarity inappearance of the first basic andadult basic plumages was presum-ably responsible for this conclusion,but this seems to be little more thanthe legacy of equating first winterand adult winter plumages in tradi-tional systems. Howell et al. (2003)argue that these similarities are

analogous, not homologous, andthey propose instead that it is morelogical for plumage nomenclature tostart with juvenal plumage. JuvenalPlumage is defined as a bird’s firstcovering of “true” (i.e., pennaceous

or non-downy) feathers, and ittends to be the plumage in which abird fledges. A bird’s juvenalplumage is a fixed point that ismore likely to be homologousamong species than the highly vari-able molt by which some or all ju-venal plumage is replaced. Birds injuvenal plumage can still be calledjuveniles, but this stage should berecognized as synonymous withfirst basic plumage. The firstplumage cycle of a bird then ex-tends from juvenal plumage to thestart of the second prebasic molt,which occurs at about one year ofage in most birds. Under the con-ventional H-P system the first cyclebegins with the start of the so-called first prebasic molt, whichcan happen any time in the firstyear or two of a bird’s life, depend-ing on the species involved; thiscomplication leads to inconsisten-cies in naming and comparingplumages that are beyond the scopeof this paper. Readers interested in

U N D E R S T A N D I N G M O L T : P A R T I I

Fig. 2. All tubenoses— like this De Filippi’s Petrel (Pterodroma defilippiana)—apparently have a Simple Basic Strategy. How could you identify this bird if yousaw it off California? To distinguish it from Cook’s Petrel, note the relatively largeand stout bill, extensive gray patches at the neck sides, and lack of a distinctblack tail tip—and the conspicuous molt on the wings. Cook’s Petrels molt theirprimaries from February through August, whereas De Filippi’s molt their primar-ies from November through April. So it is possible that a Cook’s Petrel on thedate of this photo might have started primary molt, but it would not be as ad-vanced as on this bird. Off Valparaíso, Chile; 1 February 2000. © Steve N. G. Howell.

Fig. 3. Formative plumage in many species looks much like adult basic plumage, as is the case with the Hooded War-bler. This individual looks like a classic “adult male” (i.e., in basic plumage—Hooded Warblers molt only once a year),but the relatively brown-looking alula feathers (visible at the bend of wing) suggest that this individual is, in fact, animmature in formative plumage. However, distinguishing between these two plumages in the field, or from photos,is difficult, and the safest course is to leave the age unknown. Upper Texas Coast; April 2001. © Brian E. Small.

643

prebasic molt typically commencesearlier than that of breeding adults.THE COMPLEX BASIC STRATEGY (CBS).This strategy applies to species inwhich a preformative molt (tradi-tionally termed first prebasic) isadded into the first cycle but inwhich no added molt occurs in sub-sequent cycles (Fig. 1). The prefor-mative molt replaces whateverfeathers presumably need to be re-placed in order for a bird to surviveits first year and enter into the adultcycle. The CBS is found in a widerange of species, from kestrels andkingfishers to woodpeckers andwaxwings. One reason for the fre-quent occurrence of CBS may bethat juvenal plumage grows duringthe breeding season, while adultprebasic molts generally follow thebreeding season. Consequently, thefirst cycle is usually slightly longerthan adult cycles, and juvenalplumage would have to be at leastas durable as adult basic plumage ifit were to be retained throughout

the thoughts behind this revisionare referred to Howell et al. (2003)for more information.

When this adjustment (consider-ing juvenal plumage synonymouswith first basic plumage) is made tothe original H-P system, four un-derlying patterns of plumage re-placement can be identified thatapparently encompass all species ofbirds (Fig. 1); these patterns werefirst identified, and named provi-sionally, by Howell and Corben(2000b). In terms of increasingcomplexity these four patterns aretermed the Simple Basic Strategy(called the Primitive Basic Strategyby Howell and Corben 2000b andby Sibley 2002), the Complex BasicStrategy (also called the ModifiedBasic Strategy), the Simple AlternateStrategy, and the Complex AlternateStrategy. The first two strategies re-late to birds that have only basicplumages as adults, and the secondtwo to those that also have alter-nate plumages added into the adultcycle. The differences within thetwo basic strategies and within thetwo alternate strategies occur onlyin the first cycle, after which moltsare repeated in a pattern like that ofthe adult (Fig. 1).

Before we look at these strategies,a question arises: If juvenalplumage is synonymous with firstbasic plumage, what do we nowcall the so-called first basicplumage of the original H-P sys-tem? Howell et al. (2003) proposethe term Formative Plumage, at-tained by a Preformative Molt, forany plumage that is present in thefirst plumage cycle but that lacks ahomologous counterpart in subse-quent plumage cycles. Conse-quently, the traditional first basicplumages of many species are nowtermed formative plumages, i.e.,unique, first-cycle plumages analo-

gous, but not homologous, withadult basic plumages. In essence,formative plumages are novelplumages worn by a bird in its firstyear of life as it catches up to theadult cycle of regular, stereotypedmolts (for examples, see below un-der explanation of the Complex Ba-sic Strategy).THE SIMPLE BASIC STRATEGY (SBS).This is the simplest possible moltstrategy and consists only of a sin-gle basic plumage per cycle (Fig. 1).This pattern of plumage successionis relatively uncommon, beingfound primarily in some large, long-lived seabirds (e.g., penguins,tubenoses; Fig. 2) that nest on is-lands traditionally free from preda-tors, as well as in larger raptors thathave relatively few predators. Thesespecies have relatively long chick ornestling stages during which theyoung grow a strong juvenal (firstbasic) plumage. Most or all individ-uals of these species do not breed intheir first year, and their second

W W W . A M E R I C A N B I R D I N G . O R G

Fig. 4. Most large gulls follow the Simple Alternate Strategy. This first-cycle Thayer’s Gull is largely in juvenal plumagebut has started its first prealternate molt on the mantle, scapulars, and sides of the breast. Note the fresher, grayer,and slightly contrasting new feathers. Puerto Peñasco, Sonora, Mexico; 22 January 2003. © Steve N. G. Howell.

B I R D I N G • D E C E M B E R 2 0 0 3

U N D E R S T A N D I N G M O L T : P A R T I I

644

the first cycle. Butjuvenal plumage isgenerally of poorerquality than subse-quent basic plum-ages. One possiblereason for this, forexample in passer-ines, is that nest-bound young areoften susceptible topredation, and sothey grow a func-tional, but not nec-essarily durable, ju-venal (first basic)plumage withwhich they canleave the vulnera-bility of the nest.Subsequently theyundergo a variablyextensive, preformative molt bywhich they attain stronger feathersthat protect them until the start ofthe second prebasic molt. The pre-formative molt often includes onlyhead and body feathers (as in manypasserines), or it can be complete(as in hummingbirds); it can evenvary considerably in extent within aspecies, as discussed in Part 1. Theformative plumage that results oftenlooks much like the adult basicplumage (Fig. 3).THE SIMPLE ALTERNATE STRATEGY (SAS).This strategy applies to species inwhich only a single plumage (tradi-tionally termed first basic and mis-takenly believed to comprise twoplumages) is added into the first cy-cle, and one plumage (alternate) isadded into subsequent cycles. Theadded first-cycle molt usually ap-pears to be homologous with theprealternate molt of adult cycles(Howell et al. 2003; Fig. 1). Thisstrategy is relatively uncommon andwas recognized only recently (How-

cycle molt (the conven-tional first prebasic molt)lacks a counterpart in thedefinitive cycle and is nowtermed a preformativemolt. As in CBS species,preformative molts vary inextent from partial to com-plete and typically produceplumages that look muchlike adult basic plumages(Fig. 5). Usually, the sec-ond plumage added intothe first cycle appears to behomologous to the adult al-ternate plumage (Fig. 1).Shared life-history traits ofmany CBS species are thatthey are migratory and thatmost breed, or may attemptto breed, in their first year;some combination of these

factors has presumably producedthis molt strategy. In mostly non-mi-gratory species, such as grouse andnuthatches, life-history characteris-tics such as the wear of plumage inexposed and scrubby habitats, or theabrasion of head feathers by stickingfaces into tree cavities, may havecaused these extra molts to evolve.

Table 1 (after Howell et al. 2003)classifies North American bird fami-lies by these four categories andhelps to make sense out of theseemingly wide variety of moltingregimes discussed in Part 1 of thisarticle. For example, note that allpasserines follow only two strate-gies—CBS and CAS. But note alsothat many areas of uncertainty re-main in the simple field of descrip-tive molt studies. When looking ata species whose molt is undescribed(e.g., Fig. 6), we now have onlyfour options to consider as startinghypotheses—or two choices if weknow whether the subject has analternate plumage as an adult.

ell and Corben 2000a). The SAS hasbeen identified mainly in relativelylarge, aquatic non-passerines,namely loons, pelicans, some seaducks, and some large gulls (Fig.4). In some groups, e.g., ducks andlarge gulls, the evolution of the SASmay have come about through lossof a second first-cycle molt (i.e., de-rived from the Complex AlternateStrategy, discussed below). As arule, species following the SAS donot breed in their first year, so asingle molt may be adequate to helpthem survive through their first cy-cle; that is, there is no need for twomolts, as there is in species with theComplex Alternate Strategy.THE COMPLEX ALTERNATE STRATEGY (CAS).This strategy applies mostly tospecies in which two plumages areadded into the first cycle, while oneadded plumage occurs in adult cycles(Fig. 1). Such species include manyshorebirds, small gulls, and appar-ently all passerines that have alter-nate plumages as adults. One first-

Fig. 5. Most small sandpipers, such as this Black Turnstone, have a Complex Alternate Strategy.But is this bird molting from formative plumage to first alternate plumage, or from definitive basicto definitive alternate plumage? Birders should be aware that no single system of molt terminol-ogy is “the best”; some terminologies apply better in the field, and others make more sense froman evolutionary standpoint. Bodega Harbor, California; April 1999. © Steve N. G. Howell.

continued on page 646

W W W . A M E R I C A N B I R D I N G . O R G 645

SBS CBS SAS CAS––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––NON-PASSERINES––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Loons ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Grebes ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Albatrosses ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Petrels and Shearwaters ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Storm-Petrels ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Gannets and Boobies ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Pelicans ? ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Cormorants ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Anhingas ? ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Frigatebirds ? ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Herons and Egrets ●● ● ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Ibises and Spoonbills ● ● ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Storks ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Vultures ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Whistling-Ducks ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Geese ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Ducks ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Hawks ● ●●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Falcons ● ●●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Chachalacas ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Grouse ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––New World Quail ● ●●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Rails and Coots ● ? ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Limpkin ? ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Cranes ? ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Plovers ? ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Oystercatchers ? ? ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Stilts and Avocets ? ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Sandpipers ●● ●● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Skuas and Jaegers ? ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Gulls ●● ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Terns ? ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Auks ? ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––NEAR-PASSERINES––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Pigeons and Doves ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Cuckoos ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

SBS CBS SAS CAS––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Barn Owls ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Typical Owls ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Nightjars ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Swifts ? ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Hummingbirds ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Trogons ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Kingfishers ? ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Woodpeckers ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––PASSERINES––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Tyrant-flycatchers ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Shrikes ? ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Vireos ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Crows and Jays ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Larks ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Swallows and Martins ● ●●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Titmice and Chickadees ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Verdin ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Bushtits ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Nuthatches ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Creepers ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Wrens ● ●●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Dippers ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Kinglets ● ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Thrushes ● ●●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Wrentit ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Mockingbirds and Thrashers ● ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Starlings ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Pipits and Wagtails ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Waxwings ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Olive Warbler ● ?––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Wood-warblers ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Tanagers ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Sparrows and allies ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Grosbeaks and Buntings ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Blackbirds and Orioles ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Finches ● ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––Weaver Finches ●––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Table 1 (after Howell et al. 2003). Molt strategies of North American birds categorized by family or subfamily. Legend: SBS = Simple Basic Strategy; CBS = Complex Basic Strategy;SAS = Simple Alternate Strategy; and CAS = Complex Alternate Strategy. Dark circles (●) denote the predominant molt strategy or strategies within a family (>35% of species),and light circles (●●) denote a less-frequent strategy or strategies (<35% of species). A question mark indicates that the molt strategy may occur but that confirmation is needed.

B I R D I N G • D E C E M B E R 2 0 0 3

U N D E R S T A N D I N G M O L T : P A R T I I

646

Real-life ExamplesHaving worked throughthe theory of differentmolt strategies, let’s look atsome real-life examples ofhow particular species re-late to these four strategies(and see Figs. 1 and 7).• SIMPLE BASIC STRATEGY:SHARP-SHINNED HAWK. Wehave to start somewhere,so let’s start with the egg.The chick hatches andundergoes a nestling pe-riod of 4–5 weeks thatculminates, after twodowny stages, in a strongjuvenal (first basic)plumage in which theyoung Sharp-shin fledges. Thisplumage protects the bird throughmigration and winter, when ithones its foraging techniques. Hav-ing survived the winter, and sittingout its first nesting season, the year-ling Sharp-shin takes advantage ofthe longer days and increased foodin summer, when it undergoes acomplete molt into second basicplumage before migrating south forthe winter. From here on, theSharp-shin migrates north in spring,nests, starts its prebasic molt whilestill nesting, and completes it beforefall migration. And so molt is fittedinto the annual cycle, with Sharp-shinned Hawks molting simplyfrom one basic plumage to another.• COMPLEX BASIC STRATEGY: EASTERN

TOWHEE. Like many passerines,towhees hatch mostly naked (theyhave some vestigial, wispy down ontheir upperparts). They quickly moltinto a fairly weak but functional ju-venal (first basic) plumage that al-lows them mobility, so that they canleave the nest within 10–11 days ofhatching (or even 7–8 days if dis-turbed; Greenlaw 1996). Taking ad-vantage of late-summer flushes of

tween October and Feb-ruary (Howell et al.1999). Some individuals(especially in populationsbreeding on the EastCoast) undergo a fairlyextensive prealternatemolt of head, body, andscapular feathers by mid-winter, while others (ap-parently from high-lati-tude breeding popula-tions) undergo almost noprealternate molt beforetheir first spring (Howell2001). The complete sec-ond prebasic molt startsin April and May, abouttwo months earlier than

that of breeding adults, and usuallyends by October. The second prealter-nate molt often starts in October, be-fore the second prebasic molt has fin-ished, and the molting schedule isthen similar to that of an adult—withcomplete prebasic molts from July toDecember and overlapping partial pre-alternate molts from October to April.• COMPLEX ALTERNATE STRATEGY:SCARLET TANAGER. In this species thealmost-naked hatchling quicklygrows a fairly weak but functionaljuvenal plumage that allows it toleave the vulnerability of the nest.It then takes advantage of plentifullate-summer food and replaces itsjuvenal head and body feathers plusupperwing coverts with a stronger,formative plumage similar in ap-pearance to the adult basicplumage. This plumage carries theyoung tanager through migration toSouth America, where there isplenty of food during the borealwinter. There, like the adults, it un-dergoes a prealternate molt of itshead and body feathers, plus per-haps some upperwing coverts, ter-tials, and rectrices (Pyle 1997), re-placing these feathers within only

food, they then replace their juvenalhead and body feathers plus upper-wing coverts with a stronger, forma-tive plumage similar in appearanceto the adult basic plumage. Some in-dividuals, especially of southern pop-ulations that hatch earlier and expe-rience stronger environmental ultra-violet radiation, also replace some toall of the tertials and central rectri-ces—that is, the feathers that protectthe closed secondaries and tail (Pyle1997). Formative plumage is wornthrough the next breeding seasonand then replaced in late summerand fall by the complete second pre-basic molt into adult plumage, afterwhich birds undergo only a single(prebasic) molt per year.• SIMPLE ALTERNATE STRATEGY: HERRING

GULL. When Herring Gulls hatch, theywear a downy plumage that protectsthem for the first few weeks of life andunder which a strong juvenal plumagedevelops. The juvenal (first basic)plumage is mostly full grown in 5–6weeks after hatching, and birds fledgemainly in August and September. Theprealternate molt out of juvenalplumage is highly variable in timingand starts in most birds sometime be-

Fig. 6. The molt strategy of the South Georgia Pipit (Anthus antarcticus), which breeds in the subantarc-tic Atlantic Ocean, has not been studied. But because all passerines follow either the Complex BasicStrategy or the Complex Alternate Strategy, we can predict that this little-known species will prove tohave one of these two strategies. Albatross Island, South Georgia; 26 March 2002. © Steve N. G. Howell.

continued from page 644

W W W . A M E R I C A N B I R D I N G . O R G 647

Humphrey-Parkes Terms Life-Year Terms

juvenal (first basic)

first summer

adult summer/breeding

adult winter/nonbreeding

first alternate

definitive basic

juvenile

definitive alternate

Fig. 7. Shown here is a comparison of Humphrey-Parkes (H-P) and life-year terms. Note that the H-P system is concerned only with the number of molts, whereas the life-year systememphasizes the appearance of the bird (see also Fig. 1). These systems are discussed in greater detail in the text. From Sibley’s Birding Basics by David Allen Sibley; © 2003 by David AllenSibley. Reprinted with permission from Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.

SIMPLE BASIC STRATEGY - SHARP-SHINNED HAWK COMPLEX BASIC STRATEGY - EASTERN TOWHEE

SIMPLE ALTERNATE STRATEGY - HERRING GULL COMPLEX ALTERNATE STRATEGY - SCARLET TANAGER

six months or so of fledging. Surelythose feathers would last a littlelonger, so why replace them againin winter? Thinking ahead, afterwinter the Scarlet Tanager has toundertake a long migration fol-lowed by breeding, so that the nexttime it could “find time” to molt itwould be over a year old. By thenits formative feathers could have

become too worn to function, andso a winter molt balances the equa-tion of molt, migration, and breed-ing. Thus, an alternate plumage aswell as a formative plumage fit intothe first cycle. After this first cycle,molts follow the adult pattern of acomplete prebasic molt in fall and apartial prealternate molt in late win-ter and spring.

The Humphrey-ParkesSystem vs. the Life-Year SystemAs we have seen, the H-P systemlooks simply at molts and helps usto organize and compare patterns ofmolt and plumage sequence amongdifferent species. The life-year sys-tem describes the appearance of abird as we see it in the field—whichdoes not necessarily relate to the

Humphrey-Parkes Terms Life-Year Terms

Humphrey-Parkes Terms Life-Year TermsHumphrey-Parkes Terms Life-Year Terms

B I R D I N G • D E C E M B E R 2 0 0 3

U N D E R S T A N D I N G M O L T : P A R T I I

648

pattern of underlyingmolts. Some things tothink about when try-ing to equate H-Pmolts and plumageswith what we see inthe field are the dura-tion of molts, the pos-sible overlap of suc-cessive molts (i.e., anew molt can startbefore the previousone has finished), thepotential for plumageto change in appear-ance over the courseof a single molt (e.g.,hormone changes thatcontrol color may notalways correspond toperiods of molting),and the potential for plumage tochange appearance due to wearrather than to molt.

Complete (prebasic) molts inmost passerines tend to be fairlyshort in duration and to last for atmost 2–3 months. In North Ameri-can species, these molts typicallyare discrete events that occur infall: either between the end of thebreeding season and the start ofwinter for residents, or before andafter fall migration for migrants. Inlarger species, however, with theirmore numerous and larger feathers,molts can be much more protracted(e.g., the complete prebasic molt inlarge gulls can take 5–6 months).And in birds with alternateplumages the prealternate molt canstart before the prebasic molt hasfinished, so that periods of moltingoverlap. In some cases it can be dif-ficult, if not impossible, to distin-guish between prebasic and preal-ternate molts: For example, doscapular feathers molted by anadult Herring Gull in October markthe end of its prebasic molt or the

start of its prealternate molt? With-out knowing the history of everyfeather follicle—and how manytimes it has been activated—thisquestion is not easily answered.These protracted molts mean thatsome large birds rarely hold a given

plumage per se for verylong. For example, largegulls in winter have oftenstarted their prealternatemolt in fall, so winteradults aren’t really in ba-sic plumage, as we oftentend to think.

Another point to bearin mind is that the colorand pattern of new andincoming feathers relateslargely to the hormonalstate of the bird. Thismeans that the “breedingplumage” of a sandpiperthat is not in breedingcondition in the summermonths (as occurs withsome first-year birds) canlook just like its “winter”

or “non-breeding” plumage (Chan-dler and Marchant 2001). Thus, theuse of color and pattern in trying toname plumages should be ap-proached carefully. Similarly, thecolor and pattern of feathers canchange over the course of a single

Fig. 8. This first-cycle California Gull shows at least two different patterns in its postjuvenal (firstalternate) scapulars: Most of the shorter scapulars have dark centers and broad, abraded paleedges, whereas many of the longer scapulars are fresher and plain-gray overall. Such differencespresumably reflect hormonal changes that relate to color patterns; they do not represent twodifferent molts but simply different stages in a single, protracted molt. Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco,Mexico; 5 January 2003. © Steve N. G. Howell.

Fig. 9. Shown here is a comparison of Humphrey-Parkes terms and life-year terms for the Snow Bunting, whichhas a Complex Basic Strategy. Note that the marked seasonal changes in appearance are due to wear, and not tomolt. From Sibley’s Birding Basics by David Allen Sibley; © 2003 by David Allen Sibley. Reprinted with permission fromAlfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc.

Humphrey-Parkes Terms Life-Year Terms

W W W . A M E R I C A N B I R D I N G . O R G 649

molt, particularly a protracted moltsuch as occurs in first-year largegulls: First-alternate feathers at-tained in fall tend to be brownishoverall, while first alternate feathersattained later in the molt are moreoften grayish overall, presumablydue to hormonal changes (Fig. 8).These different feather patternshelp explain why some first-yeargulls have often been assumed tohave two molts.

And then there are differences inappearance that can be broughtabout simply by the wearing off offeather tips to reveal underlyingplumage patterns. This is a less en-ergy-costly way of changing ap-pearance than molt, and it is quitecommon in passerines. Willoughbyet al. (2002) recently showed thatwear is responsible for the season-ally changing appearance ofLawrence’s Goldfinch; previously itwas presumed to have two molts(Pyle 1997). A well-known andmore readily seen example is theEuropean Starling, where the palespots of “non-breeding” plumagewear off to produce the glossy“breeding” plumage—but it is all the same ba-sic plumage in the H-Psystem. An even moredramatic example ofchanging appearancedue to wear (rather thanto molt) is found in theSnow Bunting: Thestriking differences be-tween a fresh-plumagedfall bird and a breedingmale in mid-summer arecaused by the wearingoff of pale-buff feathertips to reveal the glossy-black feather bases, andnot by molt. Thus, if weequate life-year termswith H-P terms (and

this is a good example of why sim-ply switching terms doesn’t work),the Snow Bunting’s bright “breed-ing” plumage is in fact its heavilyworn “winter” plumage (Fig. 9).And in the field it may not be possi-ble to distinguish between a first-year Snow Bunting in formativeplumage and an adult in basicplumage—yet the life-year systemallows us to describe them both aswearing “non-breeding plumages”.In fact, the Snow Bunting’s moltstrategy is Complex Basic, just aswith Eastern Towhee, but we mightnot guess this simply from watchingbirds in the field.

As is so often the case, these twosystems are different, but one is notnecessarily better: Which you usedepends on your purpose. For stud-ies of molt, the H-P system is theonly useful way to compare speciesand evaluate molt strategies. But forfield birding it is fine to use termssuch as “adult”, “first-winter”,“breeding plumage”, and so on. Infact, trying to apply H-P terms tobirds in the field implies a precisionthat may be spurious (due to the

factors discussed above).A practical compromise for birders

who aspire to more precision may beto age birds by plumage cycles,which often equate to years and, inmost North American species, corre-spond to periods between molts ofthe primary feathers. This approachavoids the problem of what wemean, for example, by a “secondyear” Herring Gull seen in February.Does this mean a bird in its secondcalendar-year (and about 7 monthsold), or is it a bird in its second win-ter of life (and about 19 monthsold)? A first-cycle Herring Gull inFebruary means the former, while asecond-cycle Herring Gull means thelatter. Cycles also get around theproblem of different seasons betweenhemispheres, or on the Equator, andare something to consider when de-scribing birds in the field.

Does Understanding Molt Help Usin the Field?It’s all very well to have an under-standing of molt, but does it haveany practical value? In short, Yes.Here are a couple of examples of

how molt can help inidentification, and po-tentially even in con-servation, based simplyupon my observationson memorable Memor-ial Day pelagic trips offNorth Carolina thispast spring. Many ofthe Band-rumpedStorm-Petrels that oc-cur off North Carolinaapparently come from“winter-breeding” pop-ulations in the easternAtlantic, because pre-sumed adults off NorthCarolina in late Maywere molting theirmiddle and outer

Fig. 10. Apart from its intrinsic interest, the study of molt may have important consequencesfor understanding bird biology and conservation. In the case of the Black-capped Petrel, for ex-ample, an index of reproductive success could be developed by carefully noting the relativenumbers of fresh-plumaged juveniles to worn-plumaged and/or molting (shown here) adults.Off Hatteras, North Carolina; Late May 2003. © Steve N. G. Howell.

B I R D I N G • D E C E M B E R 2 0 0 3

U N D E R S T A N D I N G M O L T : P A R T I I

650

primaries—a very conspicuous fieldmark when you look for it. By con-trast, Leach’s Storm-Petrels breed inthe northern summer and do notmolt primaries in May. Thus, anyBand-rumped/Leach’s Storm-Petrelwith obvious wing molt was aBand-rumped—a field mark visibleat greater distance than the conven-tional plumage marks. Being able toidentify a Band-rumped morequickly meant calling it out sooner,so that more people could see it.However, juvenile Band-rumpedsfrom the most recent breeding sea-son were in fresh plumage and notmolting, so this was only a one-wayfield mark: A Band-rumped/Leach’sStorm-Petrel without wing moltcould have been either species.

And molt might help in otherways, such as in monitoring popu-lation trends. Adult and non-breed-ing immature Black-capped Petrelsin late May are either in wornplumage (and just about to startwing molt) or, more likely, in wingmolt (Fig. 10). But newly fledgedjuveniles are in fresh plumage, withno wing molt. By carefully notingthe proportion of fresh-plumagedjuveniles to worn-plumaged andmolting birds, an index of breedingsuccess could be developed; over aperiod of ten or twenty years, thedata could be useful for monitoringand conservation.

SummaryWhile molt may seem like an over-whelming and bewildering subject,the underlying principles are fairlysimple: Every bird has to molt, andwhen and where it molts reflectsfood availability balanced with otheraspects of its life cycle, in particularbreeding and, when relevant, migra-tion. All species have a complete (ornear-complete) molt once a cycle,usually after breeding: the prebasic

molt producing basic plumage. Aminority of species (in the globalsense) fit a second molt into theirannual cycle: the prealternate moltproducing alternate plumage. Usu-ally this molt involves only somehead and body feathers, because moltis an energy-demanding process, andto replace an entire plumage twice ayear would require a lot of fuel.

By divorcing molt and plumageterminology from preconceptionsrelating to seasons or breeding sta-tus, it is possible to recognizebroad, underlying patterns offeather replacement that are inform-ative for comparative studies ofmolt. All birds follow one of fourmolt strategies: Simple Basic, Com-plex Basic, Simple Alternate, andComplex Alternate. But from thepoint of view of field birding it isstill helpful to refer to adults andimmatures, breeding and non-breeding plumages, etc. For specieswith multiple years of immatureplumage it can be helpful to applythe concept of cycles, which avoidthe potential ambiguity of someother terms.

AcknowledgmentsForemost I thank Chris Corben,Peter Pyle, and Danny Rogers forhelping to crystallize my thoughtsabout molting strategies; DannyRogers also helped prepare Fig. 1,and David Sibley kindly allowed meto use illustrations from his bookBirding Basics. Earlier versions ofthis article benefited from com-ments by Sue Abbott, RenéeCormier, Miguel Demeulemeester,Ted Floyd, Peter Pyle, and ToddThompson.

Literature CitedChandler, R.J., and J.H. Marchant.

2001. Waders with non-breedingplumage in the breeding season.

British Birds 94:28–34.Greenlaw, J.S. 1996. Eastern

Towhee (Pipilo erythrophthalmus),in: A. Poole and F. Gill, eds. TheBirds of North America, no. 262.The Birds of North America,Philadelphia.

Howell, S.N.G. 2001. A new look atmoult in gulls. Alula 7:2–11.

Howell, S.N.G., and C. Corben.2000a. Molt cycles and sequencesin the Western Gull. WesternBirds 31:38–49.

Howell, S.N.G., and C. Corben.2000b. A commentary on moltand plumage terminology: Impli-cations from the Western Gull.Western Birds 31:50–56.

Howell, S.N.G., J.R. King, and C.Corben. 1999. First prebasic moltin Herring, Thayer’s, and Glau-cous-winged Gulls. Journal ofField Ornithology 70:543–554.

Howell, S.N.G., C. Corben, P. Pyle,and D.I. Rogers. 2003. The firstbasic problem: A review of moltand plumage homologies. Condor105:635–653.

Humphrey, P.S., and K.C. Parkes.1959. An approach to the studyof molts and plumages. Auk76:1–31.

Humphrey, P.S., and K.C. Parkes.1963. Comments on the study ofplumage succession. Auk80:496–503.

Mindell, D.P., and A. Meyer. 2001.Homology evolving. Trends inEcology and Evolution16:434–440.

Pyle, P. 1997. Identification Guide toNorth American Birds, part 1.Slate Creek Press, Bolinas.

Sibley, D.A. 2002. Sibley’s Birding Ba-sics. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Willoughby, E.J., M. Murphy, andH.L. Gorton. 2002. Molt,plumage abrasion, and colorchange in Lawrence’s Goldfinch.Wilson Bulletin 114:380–392.