Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

-

Upload

noorfarhananorizan -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

0

Transcript of Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 1/14

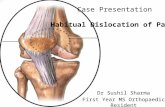

BREAKING THROUG H HABITUAL BEHAVIOUR

IS CAR SHARIN G AN INSTRUMENT FOR RED UCING CAR USE?

Reus Meijkamp

Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering, TU Delft

Henk Aarts

Faculty of Technology Management, TU Eindhoven

1. INTRODUCTION

Car Sharing is an innovative and emerging concept that raises large interests from many

societal actors, like policy makers, entrepreneurs, consumer organisations and the

individual consumers. Car Sharing is basically a service that offers rental cars as an

alternative to the privately owned car. The service is aimed at providing access to and

utilisation of a car whenever necessary. The Car Sharing concept relies on a new

organisation structure for the car system. The car is no more the users' property, but it

is owned by an organisation, the fleet manager. This fleet manager provides all its

clients with a car, whenever they need one.

The focal interest in the concept can be explained by the rather inefficient use of the

privately owned car in western societies. Although cars in the Netherlands are

relatively frequently used, on the average, they are occupied only 72 minutes a day.

(CBS, 1992) The fact that many ears are not intensively used (despite the ir large fixed

costs) and the fact that these cars put a high pressure on (scarce) space, especially in

crowded cities, make the privately owned car a rather inefficient solution for the need

for individual mobility.

For the individual consumer the relevance of Car Sharing schemes can be found in

some relative advantages of this alternative to the private car: Sharing cars is far more

cheaper for those who do not frequently use their car. The consumer has to pay only for

the use of the car, whenever needed. And the service supplier takes care for (the costs

of) the repairs, maintenance, the insurance and the taxation.

The policy relevance is basically twofold. First, by means of Car Sharing the nu mber of

cars for private purposes could be reduced significantly. Especially in crowded

innercities this means a positive contribution to the quality of living within cities and a

more efficient utilisation of scarce space. Secondly, Car Sharing is assumed to have a

positive effect on the mobility behaviour of its participants. Dutch (Meijkamp and

Douma, 1995) as well as other international, tentative studies (Muheim, 1992; Hauke,

1993; Petersen, 1993; Baum ea.., 1994), most of them small scale, suggest a reductional

effect on car use and on modal split towards relatively more public transport use.

However, until now it remains unclear how these effects can be explained, and wha t

variables influence the variations.

The p resent research aims, to examine the effects on mobility behaviour, and especially

on car use of those who already have adopted Car Sharing. Through a survey research

among participants of Car Sharing schemes in the Netherlands the behavioural effects

have been established. The present paper serves basically three goals. First, we will

explain the psychological antecedents of the adoption of the Car Sharing system by

testing a model that describes the adoption. Secondly we will present the reported

changes on mobility behaviour among the present participants in Car Sharing systems.

And thirdly, the effects on mobility behaviour of those participants will be discussed for

exploratory reasons by means of the self reported effects on mobility behaviour.

In general, the reported aggregate changes on mobility behaviour in the above

ment ioned studies have been confirmed. There fore possible explanations for the

reported changes on mobility behaviour have been developed and investigated by

making an inventory on the perceptions of the participants regarding the effects of Car

Sharing on their own mobility behaviour.

3 9

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 2/14

In search for a plausible explanation for the changes on mobility behaviour one basic

assumption is guiding: I f Car Sharing is used as an alternative to the private car, the

cognitive process involved in travel mode choices, is being influenced. Since, Car

Sharing requires planned car use, and prevents from spontaneous car usage, traveI

mode decisions are forced to be taken more deliberately. Habitual behaviour and

habi tual car use, as a consequence is therefore less likely, instead, a deliberate choice

between the various travel modes is being stimulated.

The effects on mobility behaviour of the participants will however only occur if Car

Sharing has been adopted. People, who have build up a strong car habit, won t adopt

Car Sharing at all, due to the absence of making deliberate travel mode choices. Hence,

the effects might only be expected among people that didn t built up a strong car habit.

In the remainder of the introductional sections we will elaborate on the main issues

relevant for understanding the adoption of Car Sharing systems and their potential

effects. Firs t the focus is on Car Sharing in the current practice. Next, we will discuss

some theoretical issues as to the way in which the adoption of Car Sharing may be

modelled, and the factors that may play an important role in this model. In the pape r a

discussion regarding reasoned action versus habit formation will be set up. After that,

we present our conceptual model, and proceed with empirical data concerning a test of

the model, and the subsequent effects of Car Sharing on relevant mobility parameters.

Based on the findings in the empirical study, some implications of the analysis for

transport policy regarding Car Sharing will be discussed.

2.

C R

SHARING IN PRACTICE

recent developments

Car Sharing has become an official instrument in transport policy in the Netherlands.

Both the development of supply of Car Sharing services and the adoption of Car

Sharing by the public is strongly supported by many recent transport policy initiatives

(Nora Milieu en Economie, 1997; Stichting voor Gedeeld Autogebruik, 1997; Sweers,

1996). Co-opera tion among the different suppliers is strongly encouraged and

facilitated by the government and the continuous communication of the innovative

concept to the market is realised by means of several national campaigns. Mid 1997, an

estimated 24.000 households have been registered as participant in one of the more

than 20 various schemes.

diversity in operational forms

Car Sharing is an umbrella concept for a large variety of commercial schemes aimed at

providing consumer services for car access and regular car use. All schemes can be

characterised as a kind o f (innovative) rental services. All these schemes, however ,

have to a certain extent different characteristics. The way in which the service is

delivered, varies. The outlet (unmanned in the living area or centralised at a regular

rental office), the minimum rental period (one hour or one day), the reservation time

(no need or even 24 hours), the payment procedure and the availabihty of different

type of cars are the most important characteristics that makes the various schemes

distinct from each other. In the research here, the investigations are made on the

conceptual level.

beha viou ral consequences o f ar Sharing

The concept of Car Sharing has in any case at least two major consequences for

customers in their daily practice:

1. Car use with the scheme requires planning and mostly reservation in advance.

Direct ear access is prohibited because the car is not available in front of the house.

This might facilitate to search for alternative travel modes, especially on the shorter

distances.

2. The costs of car use are based on utilisation only, without separate fixed costs.

That makes that there is a regular feedback on the costs for car use, not on a perception

basis, but on real economic basis. The full-cost accounting and its feed-back may

therefo re balance the cost benefit analysis between public transport and car use bet ter

and stimulate more frequent public transport use.

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 3/14

3. THEORY

reasoned based approaches to prediction and regulation of travel mode choices

In general research on the prediction and the regulation of individual transport

behaviour relies on expectancy value models, strongly rooted in theories of rational

choice (see, for example Ben-Akiva, 1992). The "subjective expected utility" (SEU)

model is probably one of the best known in this field (Edwards, 1954). According to the

SEU model, the estimation of the utility of alternatives can be calculated by adding the

products of the subjectively perceived likelihood's and values of various consequences

associated with each alternative. Essentially, the SEU model is concerned with the

assessment of utility o f options, that is to form deliberately attitudes about options. The

model assumes that individuals try to maximise their economic utility and tha t they

therefore use a value function to evaluate alternatives among which a choice must be

made. With regard to behaviour, the model assumes that the alternative with the

highest option is chosen.

One of the most influential and well documented expectancy-value models, that

explicitly rela tes utilities (or attitudes) to actual behaviour, is Fishbein and Ajzens'

attitude-behaviour model, also known as the theory of reasoned action (1975, Ajzen &

Fishbein, 1980). The theory o f reasoned action postulates that, prior to the execution of

an act, individuals trade off the perceived positive and negative consequences of that

act, and thus decide to per form or not to per form the behaviour. The model is widely

used in studies on the explanation of human behaviours in general, and car choice

behaviour in particular (e.g. Shepard, Hartwick & Warshaw, 1988; Aarts, 1997) Of

importance here is, that the model of reasoned action emphasises the deliberate

character o f individual choice. I t is the exactly the deliberate manne r of choice making

-which is reflected by a strong behaviour prediction value of attitudes and intentions-

that is questioned here

habitual behaviour

The last two decades, more and more research on travel mode choice behaviour have

started to argue that the model of reasoned action (and other models based on the

assumption of rational choice) ignores an important aspect o f travel mode choice, i.e.

travel mo de choices are made on a repetitive basis (Goodwin, 1977; Banister, 1978;

Verplan ken et al., 1994; Aarts, Verpl anken & Van Knippenberg, 1997). On the

average, a consumer has to make more than 1000 times a year a choice about a travel

mode. I f every trip would be a completely different one, a rational choice would be

mor e likely. However, generally, transportation behaviour consists of similar trips, on

similar conditions, like daily commuting, weekly shopping, etc.

In many studies on repeated behaviour and especially transport behaviour, which is to a

large extent repeated behaviour, researchers have concluded that what once was a

rational choice, has become repeated behaviour from the past. (see for a review,

Ouelette & Wood, 1996) Behaviour that has been performed successfully many times

tends to become habitual. Habitual behaviour can be best understood by the immediate

relationship between stimulus and response, or by the direct association between

specific trip goals and the travel mode choice, without the need to trade-off travel mode

options. We may say, therefor, that habits reflect the automatic or heuristic nature of

behaviour, while non habitual behaviours are guided by reasoning processes.

habits attitudes and intentions

The research so far (Triandis, 1977; 1980; Ronis ea., 1989; Eagly and Chaiken, 1993)

suggests that in the case of repeated actions, subsequent behaviour is determined both

by attitudes and intentions on the one hand and by habit strength on the other. That

means that, on the one hand, the relationship between choices of options relies on

deliberate decisional processes, in which attitudes towards options and the behavioural

intentions precede choices and behaviour. On the other hand the research suggests that

future behaviour and choices are guided by a heuristic or less elaborate decision

making process in which the impact of past behaviour and habits are strong. Triandis

(1977) proposed a model that describes the relationship between habit and decision

making in terms of an interaction between intention and habit in the prediction of

behaviour. In his model the probability of an act (Pa)is a weighted function of habit

(H) and behavioural intention (I), multiplied by "facilitated conditions" (F).

3

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 4/14

In fact, Triandis hypothesised that as the same behaviour is more frequently executed

in the pas t and thus increases in habit strength, the behaviour is less guided by attitudes

and intentions toward performing that behaviour. Habit strength may thus moderate

the relationship between reasoned-based concepts (attitudes and intention) and

subsequent goal-directed behaviour (see also Ronis et al., 1989). Indeed, empirical tests

of Triandis model have shown that habit and attitudinal concepts interact in the

predict ion of repeated behaviours (e.g. Aarts et al., 1997; Mittal, 1988; Montano &

Taplin, 1991).

the relevance

for

ar Sharing

The idea that travel mode choices not only are guided by attitudes and intentions,

which is fundamental for the model of reasoned action, but also driven by habits, could

have at least a threefold relevance for understanding Car Sharing and predicting the

potential effectiveness of this concept.

First, it can be expected that habitual behaviour will form a explanation of non-

adoption, and possibly a stronger explanation than the (negative) attitudes and

intentions. The mere fact that many individuals do not make deliberate choices on

travel modes, implies that these people also do not consider seriously to change to a

Car Sharing system as an alternative to the private car. Hence, The attitude towards

Car Sharing will not be very predictive for the (non-)adoption.

Secondly, Car Sharing demands implicitly from its users to differentiate more between

the various transport means, in contrast to the privately owned car. It is likely that if the

car is not immediately available, alternative travel mode options are being considered

and chosen more frequently, just because of the fact that the barrier to use a car has

increased to a certain extent. In other words, the decision making process regarding

travel mode choices is likely to become more deliberate.

And thirdly, since Car Sharing forces the individual towards a more deliberate travel

mode choices over time, it can be expected that the adoption of Car Sharing leads to

effects on mobility behaviour, and more specifically to a reduced car use.

operationaIisation o f ha bit

Habits have been operationalised in different ways in transportation research and othe r

types of psychological research. (Aart s, 1996; Eagly & Chaiken , 1993) Many

researchers have measured habit simply by asking the respondents to report on their

frequency of past behaviour. It can be questioned whether this is an appropriate

measure. Repeated occurrence is necessary for the formation of habit, but it is not the

same. Conceptually, it is being investigated to what extent decisions are based on

deliberate choices or whether the travel mode choices are made rather automatically.

Mittal (1988) concludes this discussion regarding the operationalisation of habits with

the statement: awareness is the discriminating factor . If a behaviour recurs -even very

frequently- with awareness and much deliberation, it must be considered as driven by

attitudes and intentions, and not by habit. Exactly the extent to which people form an

opinion about behavioural options and arrive at subsequent choices is relevant here.

The way in which habits have been operationalised in this study about the adoption of

Cat Sharing must be seen in the light of what this system wants to achieve with its

participants: that is to make more differentiated travel mode choices, less dependent on

solely the car. The extent to which individuals are used to trade off alternative travel

modes for the car is therefor of major interest here. For short trips, the bicycle, and for

other trips public transport , if available, can be an appropriate alternative to the car.

Thus the key of our measure of habit, is the extent to which people choose deliberately

between the car and other travel modes, as public transpor t and the bicycle.

4. HYPOTHESES

From the preceding discussion one central assumption may hold regarding the

explanation of the changes on mobility behaviour: If Car Sharing is used as an

alternative to the private car, the decision process involved in travel mode choices, is

being influenced. It can be assumed that a more deliberate travel mode choice is likely,

which results in a changed mobility behaviour.

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 5/14

For these effects to take place, it is a precondition that people have to have adopted

Car Sharing first. The adoption itself is likely to be affected by habits as well. That

means that in the adoption of Car Sharing already a filtering function with respect to

habitual decision making exists. People, who have build up a strong habit, won' t adopt

Car Sharing at all, due to the absence of making deliberate travel mode choices. Hence,

it can reasonably be expected that effects on mobility behaviour only take place among

those people who do not have built up a strong car habit.

attitude and

intention owards

Car Sharing

habit

strength

adoption of

Car Sharing

figure i. the interaction between attitude/intention and habit strength

It can be hypothesised from the forgoing theoretical framework that habit in travel

mode choices will negatively and significantly relate to the adopt ion (H1), that the

attitude and intention towards Car Sharing will be positively and significantly related to

the adoption (H2) and that a significant moderating effect of habit on the predictive

value of the intent ion on the adoption can be expected (H3).

These hypothesis will be tested fo r the (former) car owners only, for several reasons:

-Tentative foreign research suggests that for this group the effects of Car Sharing are

likely to be highest.

-For this group the change in direct car access is largest, since this group lacks suddenly

private car access. The expected effects on travel mode choices will therefore be larger.

-From a trans port policy perspective the former car owners are most difficult to

influence in their car use, and therefore most interesting for research purposes.

5. i RESE ARC H METHOD

respon ents

In the context of the national evaluation program on Car Sharing in the Netherlands,

co-ordinated and funded by the Dutch ministry of Transport ( A W ) a survey research

has been conducted (Meijkamp & Theunissen, 1997). This research was aimed at two

groups: (1) all participants of four Car Sharing schemes, as well as (2) people that

showed interest over the last year in these schemes by demanding more (specific)

information. Of four Car Sharing schemes all participants (847 households), at that

time (1996), were mailed with a response of 40 (337 questionnaires). Those who

showed once interest in one of the four schemes were mailed as well. The response rate

on 2445 questionnaires was 33 (809 questionnaires). The group of the interested is

selective and has a certain pro-adoption bias, in a sense that these people have

knowledge about what Car Sharing is; they are familiar with a specific scheme and they

showed initiative in getting more information.

EventuaUy we selected for the analysis 458 respondents , who all of them own a car, or

owned a car before participation in the scheme.

measures

adop on

Ado pt ion was identified by the criteria whet her people have signed the

contract or not

inten on towards adoption of Car Sharing Th e intention towards Car Sharing was

measured by asking whether they (the participants) were intended to extent their

contract next year, or whether they (the interested) were intended to become member

of the Car Sharing organisation the next year. The opinion was measured on a 5-point

scale, from very sure to certainly not.

3 3

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 6/14

attitude towards Car Sharing

The attitude toward Car Sharing was measured by asking

the opinion about the statement Car Sharing is for me a good alternative to a private

ear . The ir opinion was measured by a 5-point scale ranging from agree to disagree.

habit strength

Habit strength was measured by a two items scale. The statements to

which peop le gave thei r opinions (5-point scale, from agree to disagree) were: I never

trade off between the car and public transport and I never trade off between the car

and the bicycle . Both items correlated .39 (Pearsons' r) and were therefor added into

one measure.

car use (in annual mileage)

Both car use in the year before, as well as after partic ipation

was measured by asking the respondents to estimate their mileage by private, rental,

borrowed and shared car per year.

frequency of use of various transport means

The frequency of use of the various

transport means was measured by asking the respondents to estimate their weekly use,

just before participation and in the present situation. The frequency of use is measured

for cars, bicycles, intercity busses, trams and city transpor t and requested explicitly to

calculate a to-and-return trip as two trips. The frequency of car use in the pas t serves as

a measure for past behaviour.

Decisional involvement

Decisional involvement, as a measure for the awareness in the

travel mode decision making could be established by applying an 8-item scale,

developed by Aar ts (3_996).

6. RESULTS

This research alms, in general, to examine the changes in mobility behaviour, and

especially on car use of those who have adopted Car Sharing. As argued, the effects of

those who substitute the private car for a shared car are particularly interesting. Since,

it can be expected that especially this group shows substantial changes in mobility

behaviour, due to an enhanced deliberate decision making process. In the assessment of

the psychological antecedents of the adoption process however, we will address the

former car owners as one single group; whether these people finally realised

substi tution, will be lef t out, because conceptually it is not possible to differentiate to

this criterion for the interested.

a. explaining adoption and non-adoption by attitudes/intention and habit

Descriptives &

Intercorrelations a n M SD 1 2 3

1 Adoption 458 1,7 0,4

(1= adoption, 2= non-adoption)

2 Intention 452 2,7 1,3 44*

(1= positive, 5= negative)

3 Attitude 447 2,4 1,3 33** 54 *

(1= positive, 5= negative)

4 Habit 440 7,3 2,4 -24** -13 * -17 *

(2= strong, 10= weak) t3** 27.'*

5 Past beh~viour 458 6,6 7,8 28**

f r e q u en c y o f c a r u s e / w e e k /

Table 1. Descriptives o/~ measured variables among (former) car owners.

= D ec im al po in t s a r e om i t t ed .

p<.05. p<.01.

-15

Descriptive statistics.

Descriptive statistics presented in table 1. show that, for our data

(1) non-adopt ion was over represented, (2) the intentions were moderate (M=2,7 on 1-

5 scale), (3) the attitudes towards Car Sharing were moderate as well and varied widely

(M=2,4 with SD=1,3 on a 5-point scale), (4) the habi t was relatively weak, and (5)

compared with the Dutch population the respondents the respondents showed a

moderate ear use, but the variance among the sample is considerable.

Intercon elations. With respect to almost all correlations, we must conclude that the

values are rather low. Obviously, as one would expect, the highest correlations exist

between adoption and intention (r=. 44), between adoption and attitude (r= .33) and

between attitude and intention (r= .54). These three central concepts in reasoned action

theory suggest that dehberate decision making is an important factor in the explanation

of the adoption of Car Sharing.

314

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 7/14

The operationalisation of habit is a very peculiar issue in the explanation of the

adoption of Car Sharing. Habit, as operationalised by some researchers in terms of past

behaviour, correlates only very weakly with the adoption. It is however quite confusing

how this should be interpreted. Low levels of car use contribute to positave attitudes (r

=. 28), intentions (r =. 22) and finally adoption (r =. 13). In a cost benefit analysis the

frequency of use is both for practical reasons, as well as for the economic evaluation an

important indicator, and thus for deliberate decision making. On the other hand it

could also be seen as a measure for habitual behaviour. If the intercorrelations between

past behaviour, and habit ( r =-. 15) are analysed, we may conclude that pas t behaviour,

at least to a small extent expresses some relevant aspects of habits.

We also have calculated the correlation between our habit measure (in terms of the two

item scale on making trades-offs between various travel modes) and an general

accepted measure for habit in transpor t research. This last measure, the 8-item scale on

decisional involvement (Aarts, 1996), which has a high internal consistency

(Crombachs alpha = .83) and expresses the extent to which people make for every

single trip a deliberate travel mode choice, correlates (r= -.42; p< .01) substantially with

our habit measure. That means that both measure similar concepts; however decisional

involvement seems to be of less relevance for our study on the adoption of Car Sharing

r= .02, n.s.) .

t sts of hypoth sis

Table 1. shows the correlations between adoption and respectively attitude, intention

and habit. From these findings it can be concluded that hypothesis 1 is accepted, since,

though ra ther low, the correlation between adoption and habits is negative (r= -.24) and

significant (p= .000). This means in practice that the less individuals trade off

alternatives for the car in their travel mode decision making and thus behave more

habitually, the less they will be likely to adopt Car Sharing as an alternative to the

private ear.

Hypothesis 2 is accepted as well, because positive attitudes towards Car Sharing (with

an r of .33 and p= .000) and the behavioural intentions (with an r of .43 and p= .000) do

both correlate significantly with the adoption. That means that, despite the rather low

values, rational decision making regarding the adoption of Car Sharing is likely to be

true.

For the testing of the interact ion effect (H3) a diseriminant analysis has been made with

the adopt ion as grouping or the dependent variable (table 2.). The discriminant analysis

was chosen because of the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable. Three

independent variables were stepwise (F to ente r = 3,84, F to remove = 2,71) entered,

maximising the minimum Mahalanobis distance (D squared) between the two groups:

the intention (I), the habit measure (H) and the interaction variable (IxH). In the table

below the results of the analysis are shown.

Summary table

Predictor Wi[ks' Sign. Minimum Sign.

Lambda D squared

step 1 Intention (I) .8098 .0000 1,36 .000 0

step 2 Habit (H) .7797 .000O 1,66 .000O

step 3 Interaction (I x H) .7668 .0O0O 1,79 .O00O

Canonical Discriminant functions

Fcn Eigen- of Cure. Canonical After Wilks' Chi- df Sign.

value Var. Corr. Fcn Lambda square

0 .766 114,8 3 .0000

1 .8041 100 100 .4829

Standardised canonical discriminant function coefficients:

Independent variables

Intention (I) .6793

abit (H) .3971

Interaction (l x H) .2666

Discrimin ant Function coeffi cients: Function 1.

Table 2. Results of discriminant analysis on the adoption of Car Sharing

3 5

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 8/14

The discriminant function 1. is highly significant and consists of three independent

variables. All three contribute significantly n discriminating he adopters from the non-

adopters. Not only the behaviour al intention and the habit, as could have been

expected, but also the interaction term (HxI) are entered into the function. The

standardised canonical loadings are listed above, of which the reasonable loading of the

interaction term is of particular interest her. The conclusion of the discriminant analysis

is that also hypothesis 3 (H3) has been accepted. The diseriminant function 1. explains

(.4829) 2 = 23,3% of the variance.

The nature of the interaction is revealed when a sample split is made as close as

possible at the median of the distribution of the habit measure. Based on a split

between the values 7 and 8 a split has been made and then the correlations between

respectively intenti on and adopt ion and atti tude and adoption were calcula ted for the

two subgroups (see tabl e 3.).

-non split

weak habi t

strong habit

Table 3.

attitude inteni~on N

.33 * .44 * 440

.32 * .46 234

,28 * .38 * 206

Correlations of atti tude/ inten tion with the adoption.

As can be seen in table 3., for both habit groups the c orrelations are still highly

significant (p< .01). However t he difference is not very significant in a Fishers z-test, z=

.85. The intenti on-behaviour correlati on is stronger among the weak ha bit group and

this is what could have been expected. In the wea k habit group, the delibera te choice is

(a little) stronger than among those who have a stronger habit. The last group is less

guided by delibera te choices, but by habits. Thus when habits are strong 14% of the

variance is explained by the inte ntion and when habits are we ak by only 21%.

b. Descriptive results on behaviour change

bl. changes in car ownership

In the context of this paper not the fact whether people owned a car or not before

participation, is held relevant, but the actual change in car ownership. Whether Car

Sharing functions as a substitute for the private car, or, is an addi tion to the already

available transport me ans and mobili ty services, is of major interest , since only in the

first case a possible habitual behaviour could be broken through. So, not only car

ownership before participation, but also during participation should be take n into

account when analysing the hypotheses. We there fore dist inguish not only betwee n

former carless people and former car owners, but also among former car owners

between second car drivers and substituters .

The table 4. below lists the proportions of each group, and gives an overview of the

variati ons of the prop ortions among the four different schemes or subsamples. From

this table it can be concluded that Car Sharing at the moment prlmarily (71%)

functions as an addit ion to available transport services for the former carle ss, and that

9% uses it as a second car alternative.

new cardfivers

substitutere

secon d oardrivers

car ownership efore

participation

carless

car owner

car ownership during

participation

no private ca r

no pnvate car

one

or m ore pdvate cars

% respondents

71%

21%

9%

table 4. Segmentation on changes in car ownership

b2. the effects on ear mileage, overal l results

The total car mileage can be calculated by adding the yearly estimated mileages by

private car, by rental car, by borrowed car and -in the after situation- by Car Sharing -

cars (shared cars). In t he table 5. below, the results of what the respondents reporte d on

3 6

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 9/14

their own car use are listed, split up in changed car ownership. It is therefor not

surprising that although some people didn't own a car before, the (former) carless have

a considerable car mileage as we ll As a reference, the values for the interes ted people

are added.

sign. p<. 05

ear mileage

BEFORE

car mi leage

AFTER

tab le 5. C

participants

average

cartess

carowner

substauter second car

r i v e r

8450 5360 13.380 21.700

5660 * 3820 * 4.730 22.386

(-33%) (-29%) (-65%) (+3%)

langes in car mileage Ckm/year~

If the differences between the mi leages before and after are being compared, it can be

concluded that a substantial average reduction of 33% has been report ed by all

respondents, from 8450 down to 5660 kilometre s per year. Split up to changed

carownership, a clear difference between the three groups can be reported; 29%

reduc tion for the carless and a 65% reduction for the substituters, in contrast to n -non

significant- increase (+3%) in mileag e by the second car drivers. Besides the lar ge

differences in rela tive changes the absolute levels of mobility by car are substantial.

All these values suggests large variations among the participants and the interested, as

well as betwe en the participants and the interested. It can be questioned what variables,

besides former car ownership constitute the variations in changed car use.

b3. the effects on the frequency of use of the various means for transport

Besides changes in carmileage, also changes in the use of the various means for

transport have been reported by the respondents. Based on estimated frequencies of

use (per week) of the car, the train, city transport and intercity busses as well as the

bicycle, some substantial changes in mobility behaviour have be en determined, as can

be viewed in table 6. below.

pa~cipants

avemge

freq. train use

BEFORE

AFTER

freq. use inte rcity transp ort

BEFORE

AFTER

traq. use city transport

BEFORE

AFTER

c n e s s

car owner

sues~tuter

sign. p<. 05 seconcl car

driver

freq. car use

BEFORE 2,5 1,6 3,8 6,5

AFTER, of which by 2,0 ° 1,6 1,6 * 5,8

SHARED OAR 1,9 1,6 1,5 5,0

freq cycle use

BEF ORE 14,3 15,1 11,6 14,5

AFTE R 16 ,3 16,5 14,8 * 17,3

2,2 2,4 2,0 1,0

3,0 * 3,0 3,5 * 1,4

0,6 0,8 0,2 0,3

1,3 1,4 1,5 * 0,4

3,2

4,0

2,9

3,9

2,0

3,5

2,9

3,8

table 6.

Changes in frequency of use of the various travel modes (per week)

An overall reduction in frequency of car use, as estimated by the re spondents, can be

reported, from 3,5 down to 2,0 times a week, of which only a minor share can be

accounted for by private cars. In contrast to a reduction in frequency of car use, an

increase in the use of the bicycle (+5%), the train (+3%), city transport (+5%) and

ntercity transp ort (+58%) has been reported. These results suggest that the reduction

m car use and an increase in the use of alternativ e travel modes, are connected. A

travel mode shift seems to be one of the effects too on the mobility behaviour of the

participants of Car Sharing schemes. From these results it can be concluded that,

although the amount of trips increases with 1%, the relat ive importance of the cars in

the provision of mobility has been reduced from 13% to 7%.

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 10/14

Again, substantial differences in changes of mobility behaviour have been reported

between the former car owners and the former carless. In general, the substitutional

effects seem to be much stronger among substituters. For t he rel ative importance of the

car in fulfilling mobility needs, it can be questioned here again which variables

constitute the variations.

c. Qualitative changes in mobility behaviour

The above reporte d changes provide insight in the effects on mobility behaviour among

the respondents. These effects -over a year- are however on a highly aggrega te level,

and do not suggests which kind of habits are being maintained within a patter n of

mobilit y behaviour and which habits are (being) changed. For exploratory purposes 19

items with a 5-point Likert scale have been formulated, that enable to get some further

insight in possible changing habits related to th e a doption of Car Sharing. The items

question some possible effects of Car Sharing as perceived by the participants. The

table 7.-below shows the scores on the items (1 = agree, 5 = disagree) and the overal l

percentages of agreement.

Since

I

participate in Car Sharing ,

choose m ore consciously how to travel.

use th e car more consciously.

I kno w better w hat car driving costs.

it makes it easier to visit people far away.

combine more often my tdps.

am likely to take the car in the weekends.

we do not use the car for shoppin9 anymore.

we make, within the household, more car trips.

the car has no t been used (anymore) for commuting.

I take the bicycle or go w alking more often.

we use the only for holidays and leisure trips.

we make, w ithin the household, far less short trips by car.

we make, with in the household, less

e a r

thps.

I travel far mor e by p ublic transport.

I travel far more by train.

I am likely to take the car in the evenings.

it is mor e like ly to take the ca r for holidays.

I stay more often at home.

earless

average

score

2,4 2,4

2,6 * 2,8

2,7 2,7

2,8 * 2,5

3,0 3,0

3,1 • 3,0

3,1 • 3,2

3,2 * 2,8

3,3 * 3,5

3,3 * 3,6

3,3 * 3,3

3,3 • i 3,6

3,4

•

I 3,8

3,6 I 3,8

3,7 * 3,9

4 , 0 4 , 0

4,0 3 ,9

4,0 * 4,2

4,3 4,3

table 7. Qualitative changes in mobility behaviour

s i gn i f i c an t d if f e r e nce s be t w e e n t h r e e g r oups , one - w a y A N O V A , pos t - hoe S c he ff ~ - t es t

earowner

suhstltuter second car

ddver

2,0 2,7

1,8 2,8

2,5 2,8

3,6 3,4

8,3 2,8

3,1 4,1

2,8 3,7

4,3 4,2

2,4 4,0

2,4 3,5

8,1 4,4

2,4 3,5

2,0 3,3

2,7 3,9

3,1 3,7

4,0 4,1

4,2 4,5

3,5 4,3

4,5 4,2

The research provides, based on self reported changes some remarkable results

concerning qualitati ve changes in mobility behaviour. Overall, regarding the effects on

the cognitive process with respect to travel mode choices a large agreeme nt among all

respondents seems to exist. This supports the basic assumptions that have been

formulated on t heoretic al grounds. Rela tively high percenta ges of parti cipant s agree

•nith the statements that ar Shariug makes th em choose mo~e consciously trave[

modes, and use the car more consciously as well. Above all many (51 of all

participants) agree with the fact that Car Sharing raises cost knowledge about the car. It

must be stressed that these effects are perceptions that do not necessarily have to

correspond exactly with what really changed.

From the table 7. it can be concluded that the effects differ among different user

groups. The distinction has been made with regard to the changed situation in car

ownership. The former carless enjoy within the Car Sharing scheme a larger car

availability.That seems to have consequences for their mobili ty behaviour: it enhances

their possibilities to visit more remote places, and it seems to stimulate car use. In

contrast to the report ed frequency of car use -that would remain unchanged- and to the

repor ted mil eage -that would have been reduced with 29 - the former carless agree

relative ly stronger with the stat ement that Car Sharing make them drive more frequent

by car.

The former car owners have been split up into those who have substituted and those

who still have their car, besides their membership. In the results that ma kes a

difference:

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 11/14

The substituters state, stronger than the others that they use the car more consciously.

In comparison to the others, they tend to be more influenced in their car use for

shopping, for commuting, in their use of the car for short trips and in general in their

frequency of car use. This is supported by the reported changes in frequency of car use.

Compared to the others they seem to substitute the ear stronger for train use and even

the bicycle.

Regarding the second car drivers the results suggest that these people are being least

influenced in their mobility behaviour. They still have a car at their disposal. The

shared car is thus an addition to their option. High values on the more conscious travel

mode choices and the more conscious car use suggest that social desirable answers are

very likely. It is hard to see how their availability of cars, which has rather increased,

could have any effect on travel mode decision making.

7. -CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

The title of this paper Breaking through habitual behaviour, Is Car Sharing an

instrument for reducing car use? suggested that Car Sharing, when adopted, results in

a less habitual mobility behaviour and thus in a reduced car use. This suggestion is

actually put forward by most of the empirical studies till now on the effects on mobility

behaviour of Car Sharing (Muheim, 1992; Petersen, 1993; Baum ca., 1994). This study

shows that, at least in the Dutch practice, it is not possible to characterise the effects of

Car Sharing on mobility behaviour with breaking through habits , since that would

mean that people would change their decisions regarding travel mode choices from a

rather habitually based process into a rather deliberately one by adopting Car Sharing

as an alternative to the private car.

In this study we first investigated the role of habit in the adoption o f Car Sharing. We

showed that habit influences the adopt ion negatively. By an mcreasing habit in travel

mode choices, operationalised in this study as the extent to which people trade-off

between the car and alternative travel modes, the adoption becomes less likely. As a

consequence we may expect tha t the adoption decision selects the people that finally

use Car Sharing as an alternative to the private car. The participants, as a results will be

less habitual in their travel mode choices. It can be expected as well that this

selectiveness in the participating population affects the influences on behavioural

changes as well.

Obviously, in the adoption of Car Sharing the attitude and the intention play a

dominant role. The importance of these two central concepts of reasoned action

prove that deliberate choices regarding the pros and cons of Car Sharing, as an

alternative to the private car are underlying the adoption decision. In this study it is not

investigated how these attitudes and intentions regarding Car Sharing are being

formed. It can be questioned which factors contribute to a positive and negative

opinion about Car Sharing. For b oth marketing purposes, as well as for transportation

policy purposes, it would be indispensable to study further the evaluation process of

consumers regarding the pros and cons of Car Sharing. As Car Sharing seems to have a

high potential for reducing the amount of cars (in crowded cities) further stimulation of

the concept would be beneficial from a societal perspective.

For a further understanding of Car Sharing, the mediating effect of habit on the

attitude-intention-adoption process (the reasoned action), is also of importance. In this

study we showed an ra ther modest interaction effect of habit on the (reasoned) decision

making process in the prediction of the adoption, that is the relation between attitude/

intentmns and the adoption: In case of a strong habit the relation between people's

opinions and their intentions regarding Car Sharing play a less important role in the

explanation of adoption, than in the case of a weak habit. That means that non-

adoption could be explained differently from the adoption of Car Sharing. In case of

adoption, it is very likely that people become a participant o f such schemes, because

they acknowledge the benefits of these systems for their situation. In case of non-

adoption, instead of the negative opinion towards Car Sharing, habitual behaviour

seems to play an impor tant role. Merely the fact that people do not trade-off between

Car Sharing and the private car, or between the private car and other travel modes,

prevents them from building up an opinion about Car Sharing and thus from a

deliberate, but negat ive or positive decision. In order to convince these people, it is

3 9

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 12/14

important not only convince them in their reasoning, but foremost to break trough their

habits and stimulate them to make a deliberate decision about whether or not to adopt.

In needs luther research how the habitual behaviour of the non-adopters could be

broken through.

The title also questioned whether Car Sharing would be an instrument for reducing car

use. We have in this study also reported on the behavioural changes of the participants.

Not only the changes in car use, but also the changes in the use of alternative travel

modes have been established, based on self reported behaviour of the participants.

These estimations showed e.g. that, especially among those who substituted their

private car for Car Sharing, realised a considerable reduction in car use of 65%, in

contrast to an increase in the use of alternative travel modes.

For this substantial change in mobility behaviour it is difficult to provide one single

explaining factor. Certainly the adoption of Car Sharing and the inherent properties of

such schemes, is one of the (important) contributing factors, however no controlling for

many-determinants of mobility behaviour has been performed. By means of an

investigation on the perceived effects of Car Sharing on the participants' own mobility

behaviour, some empirical evidence has been found for some theoretical explanations

regarding the effects of Car Sharing. In general, it could be expected that participants in

Car Sharing schemes differ from non-adopters on their habit strength and that these

people seem to be influenced, according to their own percept ions in their decision

making process regarding travel mode choices; that means that participants in contrast

to private car owners choose more consciously their travel mode, and that they have a

bette r cost knowledge about cars. To what extent these perceptions of the participants

relate to the actual changes in decision making, and to what extent these possible

influences relate to the reported behaviour changes is still unclear. Fur ther research to

clarify the changes in mobility behaviour must be conducted in order to be able to

explain these changes and the variation in changes of mobility behaviour. As a

consequence, in the future research more attention must be paid to a further

segmentation in users groups with regard to the changes on mobility behaviour. At

least, as reported and perceived by the participants themselves, some important

differences need further explanation.

Answering the question whether Car Sharing is an instrument for reducing car use must

be related to the research design and the sampling. The reported changes on mobility

behaviour refer only to a rather selective group of participants of Dutch Car Sharing

schemes and form a very specific group of so called lead-users . As we have shown,

this group is a selected group, with both specific psychological characteristics (habit), as

well as specific mobility behaviour. By no means we can therefor extent the

behavioural changes directly to a larger population of potential future participants of

Car Sharing schemes, moreove r because no clear explanation for the reported changes

could be given yet. However, given the positive changes from a policy perspective, we

may conclude that Car Sharing deserves, despite a lack of insight in the relevant

psychological mechanisms, bather support from local and national governments, and

that it certainly has -a yet unknown- marke t potehtial.

R E F E R E N E S

Aarts, H. (1996).

Habits and decision making the case o£ travel mode choice

Dissertation, KU Nijmegen.

Aart s, H. (1997).

Predicting behaviour from actions in the past: repeated decision

making or a matter of habit?

submitted for publication

Aarts, H., Verplanken, B. & Van Knippenberg, (1997). Habit and information use in

travel mode choices.

Acta Psychologica

1996, 1-14

Ajzen, I. & Fishbein, M (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social

behaviour.

Engiewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Banister, D. (1978). The influence of habit formation on modal choice: a heuristic

model.

Transportation

7, 5-18.

Baum, H. en Pesch, S. (1994).

Untersuchung der Eignung von Car-Sharing ira Hinblick

auf Reduzierung von Stadtverkehrsproblemen. Insti tut bar

Verkehrswissenschaft an der Universit~t K6in.

Ben-Akiva, M. (1992).

The evaluation of transport models: A twenty year review.

32

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 13/14

Keyno te presentat ion PTRC.

CBS (1992) Au to s in Nede rland. Cijfers over gebruik, koste n en effecten, Voorburg /

Heerlen.

Eagly, A.H . Chaik en, S. (1993).

The psycholog y o f at t itudes .

For t Worth (TX):

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Edw ards, W. (1954). The theo ry of de cision making. Psychological Bullet in, 51,380 -

417.

Fish bein , M. Ajze n, I. (1975).

Belief atti tude intention and behaviour: an

introduct ion to theo ly and research.

Reading (MASS>) A ddison-Wesley.

Good win, P.B. (1977) Habit and hysterisis in mo de choice. Urban Studies 14, 95-98.

Hauke, U. (1992).

Car-Sharing: eine empitisch e Zielgrnppenana Iyse un ter

Einbe z iehun g soz ialpsychologisehe Asp ek te z ur Ablei tung einer Market ing-

Konzep t ion .

Diplom -arbeit im Faeh Psychologic, Univers i tat Kiel .

Meijkam p, R.G. en Dou ma, G. (1995) Een evaluatie van gedee ld autogeb ruikin

Leiden

TU Delft , Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering.

Meijkam p, R. Theunisse n, R. (1996).

The Car Sharing: Consu mer Acce ptan ce and

changes on mob i l i ty behaviour

in: PTRC . Proceedings 24th PTR C E urope an

Transpor t Forum, London

Meijkam p, R.G. Theun issen, R. (1997).

De Deelan to in Neder land .

(report on the

• evaluat ion program among four Car Sharing schemes). Minst ry of Transport ,

R o t t e rdam / T U D e l ft

Mittal , B. (1988). Achieving highe r seat-belt usage: the role of habit in bridgin g the

att i tude-behav iour gap.

Iournal of Appl ied SociaI Psychology

18, 993-1016.

Montano , D.E. Tapl in, S.H. (1991). A test of an expanded theory of reaso ned act ion

to predict mz mmo graphy part icipation.

Social Science and M edicine

32, 733-

741.

Mu heim , P. (1992)

Das energiesparpotential des gemeinschaff l ichen gebrnuch s von

Motor fahrzeu gen als Al ternat ive zu m Be s i tz eines eigenen Autos

Bundesamt

for Energiewirtschaft , Bern

Mu heim , P. (1996)

Car-Sharing-Forschung, eine Recherche, Luzern

Nota Mil ieu en Econ omie (1997). Pol icy plan o n th e integrat ion of envi ronmental

i ssues in the economy. Dutch government . SDU Den Haag.

Nieuw sbrief (1997). Stichting voor G edeeld Au ogebruik, Utre cht, Jaarg ang 3, num me r

2, jun i 1997

Oue lette Wo od, (1996)

Habit : Predicting frequent ly-occurr ing behaviours in cons tant

contexts

(man..uscrpt subm itted f or pu blication) .

Peter sen, M. (1993)

Okon omische A nalyse d es Car-Sharing

Doktorarbei t

Wirtschaftswissenschaftder TU Berl in.

Ronis, D.L., Yates, J.F. Kirscht, J.P. (1989). Att i tudes, decisions, and ha bits as

determinants of repea ted behaviour. In: A.R. Pratkanis, S.J . Breclder QA.G.

Greenwald (Eds.) ,

Att i t ude s tructure and function.

Hfllsdale, NJ: Erlbau m.

Shep pard, B.H., Hartwiek, J. Warshaw, P.R. (1988). Th e theory of reas one d action: a

meta analysis of past research wi th recomm endat ions for modifications and

future research.

Journal of Consu mer research

15,325-343.

Swe ers, W. (1996)

The Car Shar ing pol icy in the Nether lands . Mar ket incent ives for

service arrangem ents that en courage selective car use.

in: PTRC. Proceedings

24th PTRC European Transpor t Forum, London

Triand is, H.C. (1977).

Interpersonal behaviour.

Monterey (CA): Brooks /Cole

Publishing Company.

Triand is, H.C. (1980).

Values atti tudes and interperson al behaviour.

In: I-I.E. Howe , Jr.

Page, M. (Eds.), Nebras ka S ymposium on Motivation, 27. Lincoln (NE):

Universi ty of N ebraska Press.

Verp lanke n, B., Aarts, H., Va n Knipp enberg , A. Va n Knip penb erg, C. (1994).

At t i tude versus general habi t: A ntecedents o f t ravel mo de choice.

Iournal o f

App l ied Social Psychology.

24, 285-300.

32

7/23/2019 Breaking Through Habitual Behaviour is Car Sharing an Ins Maent for Reducing c

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/breaking-through-habitual-behaviour-is-car-sharing-an-ins-maent-for-reducing 14/14

![Habitual Offender Laws - ncids.org Training/Kicking It Up... · Habitual Offender Laws Habitual Felon Law [G.S. 14-7.1 through 14-7.6] Being an habitual felon is not a crime but is](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5f51df19f815147c2902865d/habitual-offender-laws-ncids-trainingkicking-it-up-habitual-offender-laws.jpg)