The Status and Distribution of Freshwater Biodiversity in the Western ...

Biodiversity in the Western Ghats.pdf

Click here to load reader

Transcript of Biodiversity in the Western Ghats.pdf

BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, researchlibraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research.

Geographical Indications and Biodiversity in the Western Ghats, IndiaAuthor(s) :Claude Garcia, Delphine Marie-Vivien, Chepudira G. Kushalappa, P. G. Chengappa, and K.M. NanayaSource: Mountain Research and Development, 27(3):206-210. 2007.Published By: International Mountain SocietyDOI: 10.1659/mrd.0922URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1659/mrd.0922

BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, andenvironmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books publishedby nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses.

Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance ofBioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use.

Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiriesor rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder.

A protective label

A geographical indication (GI) identifiesa good as originating in a country, aregion or a locality where a given quality,reputation, or other characteristics ofsuch a good are essentially attributable toits geographical origin.

GIs were developed to protect con-sumers, offering reliable informationabout the goods they buy. It was initiallythought that GIs could also afford protec-tion to producers by fighting against

unfair competition and “reputation theft.”The third generation of GIs extended thisconcept to the rural landscape. If theycould be used to protect producers, theycould be used for rural development.Only recently was the concept extended tothe environment and to the cultural andbiological diversity associated with produc-tion. What remains to be seen is whetherand how GIs can have an impact on themanagement and conservation of the cul-tural and biological diversity associatedwith products.

Geographical Indications and Biodiversityin the Western Ghats, IndiaCan Labeling Benefit Producers and the Environment in a Mountain Agroforestry Landscape?

Claude GarciaDelphine Marie-VivienChepudira G. KushalappaP.G. ChengappaK.M. Nanaya206

Mountain Research and Development Vol 27 No 3 Aug 2007: 206–210 doi:10.1659/mrd.0922

A geographical indication (GI) is a form ofprotection highlighted in the Trade RelatedAspects of Intellectual Property Rights(TRIPS) Agreement of the World Trade Orga-nization (WTO). It protects intangible eco-nomic assets such as the quality and repu-tation of a product through market differenti-ation. It is considered a promising tool atthe international level to maintain multifunc-tionality in rural landscapes and involve

local populations in biodiversity manage-ment and conservation. Using the exampleof an existing GI for Coorg orange, a cropfrequently associated with coffee agro-forestry systems in the mountain region ofKodagu (Western Ghats, India), we discusshow a GI can be successfully used by localproducers and what conditions are neededfor it to have a positive impact on the land-scape and its associated biodiversity.

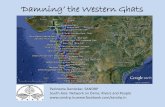

FIGURE 1 Kodagu district (A) islocated in the Western Ghatsof India (B). Land use (C) hasundergone drastic changesover the last 30 years, withcoffee plantations replacingforest—essentially medium-elevation, wet evergreen forest.(Source of maps: FrenchInstitute of Pondicherry)

Development

207

The legal framework

India has taken the lead in protecting itsorigin-based products and associated tra-ditional knowledge (TK) through the pro-motion of GIs, with a sui generis protectionsystem that is regarded as a model for oth-er countries. Conflicts over spotlight prod-ucts such as Basmati rice and Darjeelingtea have created nationwide awarenessand, in accordance with the WTO agree-ment on TRIPS, India passed the Geo-graphical Indication of Goods Act in 1999,which entered into force in 2003.

Until now, there have been more than80 applications for GIs in the field of tex-tiles, handicrafts, and agricultural prod-ucts. More than 30 have been registered.Darjeeling tea is one of the best examplesof agricultural products originating inmountain areas that had the required rep-utation and historical evidence to success-fully apply for a GI. The application mustshow the uniqueness of the product dueto its geographical origin—a combinationof human and natural factors. The appli-cation includes a description of themethod of production, historical proof,and a map.

Two types of stakeholders are directlyinvolved in a GI. The first is the applicant;the second is the authorized user of the

GI. The applicant can be any associationof persons or producers, or any organiza-tion or authority representing the interestof the producers of the concerned goods.Should the application be successful, theapplicant will become the registered pro-prietor of the geographical indication.Since the registered proprietor representsthe interests of producers, a GI is sup-posed to be a collective right.

Kodagu district: a multifunctionallandscape mosaicKodagu district in Karnataka state(75°25′–76°14′ E, 12°15′–12°45′ N) is amajor coffee-growing region located inthe Western Ghats mountains (Figure 1).It produces nearly one-third of Indian cof-fee, mostly in agroforestry systems undernative tree cover. The district name underBritish rule was Coorg, and it is under thisname that the product we discuss here isknown today. We refer to Kodagu whenspeaking of the district, and to Coorgorange when we discuss the product.

Forest represents almost 50% of thedistrict. Central Kodagu is dominated byagricultural land, essentially coffee estatesthat cover 30% of the total area of the dis-trict. Coffee in Kodagu is grown undertree shade. The other crops associated

FIGURE 2 Landscape mosaicin Kodagu district: paddy fieldsoccupy the lowlands whilecoffee plantations and forestfragments are located on thehilltops. A belt of forestreserves and protected areassurrounds the district, as seenon the horizon. (Photo byClaude Garcia)

Claude Garcia, Delphine Marie-Vivien, Chepudira G. Kushalappa, P.G. Chengappa, and K.M. Nanaya

Mountain Research and Development Vol 27 No 3 Aug 2007

208

with coffee are pepper, cardamom,oranges, and rice in paddy fields. Alto-gether, forests and agroforests account fornearly 80% of the district.

The landscape mosaic in Kodagu iscompleted by the existence of forest frag-ments embedded in the human-dominat-ed landscape of the coffee belt (Figure 2).Those forest remnants improve landscapeconnectivity, serving as corridors fornumerous species. Together with the cof-fee plantations, they provide a series ofenvironmental services in terms of pollina-tion, carbon sequestration, and waterrecharge that the scientific community isonly now starting to assess. An assessmentof the Kodagu landscape would be incom-plete if there was no mention of the rolesacred forests play in village life and in theidentity and ethos of the inhabitants.

Over the last 30 years, in response toexternal market-driven dynamics, intensi-fication of coffee cultivation has led to theloss of 30% of the forest cover, essentiallyin the species-rich wet evergreen belt ofthe district. Hence, massive landscapefragmentation, habitat loss, and biodiver-sity depletion are continuing.

Still, Kodagu is known for its excep-tional biodiversity. The question is howthis reputation could be used to valorizeorigin-based products whose quality stemsfrom this high biodiversity. A possiblestrategy could be to use a GI, providedthat the specifications for the GI applica-tion are environmentally friendly andcompatible with the maintenance of thelandscape mosaic.

Coorg orange: GI administrationand the planterThe GI applicationCoorg orange (Kodagina kittale, Citrus retic-ulata) is an ecotype of mandarin (Figure 3). It is a small tree that grows wellin evergreen, subtropical hilly tracts at ele-vations between 600 and 1200 m. Itrequires annual rainfall of 80–200 cm anda warm winter climate. Coorg orange was acrop frequently associated with coffee, butdiseases and lack of interest among farmerseager to involve themselves in more lucra-tive cash crops (coffee and pepper) havealmost entirely wiped out the crop over the

last 50 years. The Department of Horticul-ture (DoH) of the government of Karnata-ka filed an application for a “CoorgOrange” GI, which was registered in 2004.

The GI application in itself is a 9-pagepublic document. It describes the fruitand provides information about the kindof soil and bioclimate in which the orangegrows. It makes little or no mention eitherof the landscape mosaic associated withthe crop or of the traditional knowledgeassociated with cultivation of the crop.The map provided is not limited toKodagu, as it also includes the districts ofHassan and Chickmangalur, which arealso coffee production areas.

The role of the administrationIn response to the conflicts over Basmatirice, the government of India took admin-istrative steps to identify and protect localvarieties and local products, in a push forprotection against biopiracy. The GI onCoorg orange was then filed by the DoH,in a top-down, pro-active approach. Sinceit represented the government, the ration-ale was that it would stand in for theorange producers, who, in the view of theDepartment, were too few and too unor-ganized to bear the costs of drafting theGI application.

The two main objectives pursued bythe DoH were to protect and revive a tradi-tional crop variety and to provide highquality (disease-free) plant material, bring-ing economic development to the region(Figure 4). A third objective appeared lat-er, once the GI had already been regis-tered: it could be used to protect theecosystem where the orange is grown.

Transferring the GI to producersTo be successful, a GI should rest in thehands of the producers located in thearea. Therefore, it should be drafted whileconsidering the knowledge producers haveabout cultural practices, which should beembedded in the specification. Only thencan the cultural and biological diversityassociated with the product be maintainedin the area by their proprietors. The mainchallenge faced now by the DoH is success-ful transfer to the producers.

This particular GI is meant as a toolfor marketing the orange, even if until

“We are not the owners ofthe GI, we are theguardians. We will handover the ownership to theproducers.” (Departmentof Horticulture)

FIGURE 3 Coorg orange is known for itssweet taste, its greenish color, and itstight skin. (Photo courtesy of DoH)

Development

209

now no cases of misuse have been encoun-tered. The strategy of the Department isto educate the farmers about the GI, con-sidered a collective right, and then try togather them in a registered society towhom the ownership of the GI can betransferred.

In order to liaise with the producers,an arrangement was made via a local NGO,Kodagu Model Forest Trust (KMFT). TheDoH asked KMFT to revive cultivation via apackage of organic methods to be pro-posed to the planters. Outreach began,with farmers identified throughout theentire district. But transfer has stalled,since there is uncertainty over whether ornot the organic package should be part ofthe Coorg Orange GI. The DoH will retainthe GI until they feel that planters haveorganized themselves and adopted goodpractices. According to the DoH, farmerswill then need to produce a commercialdevelopment plan (fruit/juice/brandname) and publicize the product and itsGI legal aspects in local papers.

Obstacles

Several challenges must be faced whichcould impair successful transfer of the GI.First, there is a serious lack of awarenessamong the planters about what a GI is.This is slowly changing, through outreachand dissemination from NGOs, govern-ment agencies, the media, and theresearch projects present in the area. Sec-ond, the package developed aims to pro-mote best practices among the orange andcoffee growers. It is based on the assump-tion that, aware of what services they getfrom their environment, growers willstrive to maintain it. But much as the gov-ernment through its agencies and theNGOs might wish to embed the multifunc-tionality of the landscape in the GI, therealso seems to be a lack of awareness aboutthis aspect among the planters (see Box).

Third, relations between the produc-ers and the current owner of the GI areshaky at best. And fourth, it could beargued that the package of organic prac-tices advocated by KMFT and the DoH isnot an integral part of the GI or of theproduct itself. This can be added in anamended GI application, but with the

result that it would exclude any othermethod of cultivating Coorg orange. Assuch, it could probably be challenged suc-cessfully if planters raised an objection.

Lessons learned and the wayforwardTo this day farmers do not use the GI tomarket their oranges, and the supply chainis very limited. Based on the initial interac-tions KMFT had, it is now proposed thatother methods of cultivation should also bepermitted—but a few basic organic pack-ages have to be implemented. KMFT andthe DoH are working out an arrangementto register the Kodagu Orange GrowersCooperative Society as an authorized userof the GI. Surprisingly, no stakeholder hasyet come up with a proposal to actuallyamend the GI specifications so as to includeenvironmentally sound practices (Figure 5),even though this option is clearly providedfor under the Indian GI act.

The example of the Coorg orangeprovides an opportunity to discuss how aGI can be successfully used by local pro-ducers, and what conditions are neededfor it to have a positive impact on thelandscape and on conservation of bothbiological and cultural diversity. As things

FIGURE 4 Coorg orange tree: the crophas all but vanished from the district. Itnow remains only in pockets where itseems to be resistant to diseases.(Photo by Claude Garcia)

Lack of knowledge and lack of trust

Q. “What do you or your farm get from thesurrounding areas?”A. “We do not get any help or services fromthe surrounding area (landscape).”Q. “What about rivers?”A. “We don’t use the water; we have our ownwater tank.”Q. “What about forests?”A. “More than help from forests we haveproblems from it, like elephants.”(MB, Nittur village)

“Whatever I take, I pay for it and take; …once I pay, it is not a service… We callsomething service when it is free.” (MA, Devarapura village)

“They sit somewhere and tell us to dothings. I know more things than many ofthem [agronomists, horticulturists] about theproblem.” (AP, Mallur village)

Claude Garcia, Delphine Marie-Vivien, Chepudira G. Kushalappa, P.G. Chengappa, and K.M. Nanaya

210

stand today, the Coorg Orange GI mayhave prevented this local variety from dis-appearing. However, several conditions

make it doubtful that this GI will have animpact on the biodiversity and landscapedynamics of Kodagu:

• The way the GI was initiated, via a gov-ernment agency speaking on behalf ofthe producers rather than by the pro-ducers themselves;

• The fact that the specification was notdrafted with the objective of maintain-ing and fostering multifunctionalitywithin the landscape;

• The lack of local awareness of the envi-ronmental services provided by thelandscape and of the GI tool itself.

For a GI to be successful it needs tosecure income for the producers. For thisto happen, the GI needs to be filed or atleast appropriated by the producers. For aGI to be successful in protecting biodiversi-ty, the environmentally sound practicesidentified need to be embedded in thespecification of the GI. But choosing envi-ronmentally sound practices involvesopportunity costs that need to be takeninto account, lest the GI fail to becomeprofitable and therefore defeat its purpose.

FIGURE 5 Coorg orange harvest: planters used to grow orange as a single crop. It is nowgrown in association with coffee, even though both crops have different shade requirements.(Photo courtesy of DoH)

India University – CIRAD, 73 av. Jean François Breton,34398 Montpellier Cedex, [email protected]

Delphine Marie-Vivien works in CIRAD’s InnovationResearch Unit. She is currently based at the National LawSchool of India University, Bangalore, working on a PhD incomparative law, on GIs in India, France, and Europe.

Chepudira G. KushalappaUniversity of Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore, College ofForestry, Ponnampet 571216, South Kodagu, [email protected]

Chepudira Kushalappa is an Associate Professor at theDepartment of Forest Biology and Tree Improvement at theCollege of Forestry in Kodagu. He has been working oncommunity management of sacred forests and on the firstModel Forest program for India, implemented in Kodagu.

P.G. ChengappaUniversity of Agricultural Sciences, Vice-Chancellor’sOffice, GKVK, Bangalore, 560065 Karnataka, [email protected]

P.G. Chengappa is the Vice Chancellor of the Universityof Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore. He has collaboratedwith a number of institutional bodies, including the IndianCoffee Board and the International Food Policy ResearchInstitute. He has extensive experience in developing mar-ket chains for agricultural products and added value.

K.M. NanayaFrench Institute of Pondicherry, 11 St Louis Street,PB 33, 605001 Pondicherry, [email protected]

K.M. Nanaya holds a post-graduate position in forestry

and is currently working as a GIS expert with the FrenchInstitute of Pondicherry.

FURTHER READING

Bhagwat S, Kushalappa C, Williams P, Brown N. 2005.The role of informal protected areas in maintaining biodi-versity in the Western Ghats of India. Ecology and Soci-ety 10(1):8 (online). http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol10/iss1/art8/; accessed on 10 May 2007.Garcia C, Pascal JP. 2006. Sacred forests of Kodagu:Ecological value and social role. In: Cederlöf G, Sivara-makrishnan K, editors. Ecological Nationalisms: Nature,Livelihoods, and Identities in South Asia. Seattle, WA: Uni-versity of Washington Press, pp 199–225.Marie-Vivien D, Thevenod E. In press. Which protectionfor foreign geographical indications in Europe? Issuesraised by the decision of the WTO dispute settlementbody. In: Special issue of Economie Rurale. Availablefrom Delphine Marie-Vivien.Muthappa PP, Chengappa PG, Prakash TN. 2001. AResource Economic Study on Tree Diversity in CoffeeBased Plantations in the Western Ghats Region of Kar-nataka. Bangalore, India: TOENRE [Team of Excellence inNatural Resource Economics], National Agricultural Tech-nology Project, Department of Agricultural Economics,University of Agricultural Sciences, Bangalore.Ramakrishnan PS, Chandrashekara UM, Elouard C, Guil-moto CZ, Maikhuri RK, Rao KS, Sankar S, Saxena KG.2000. Mountain Biodiversity, Land Use Dynamics, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Oxford, United Kingdomand New Delhi, India: UNESCO [United Nations Educa-tional, Scientific and Cultural Organization] and IBH Pub-lishing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper is an outcome of Biodival-loc (www.ifpindia.org/Biodiversity-and-Geographical-Indications-in-India.html),a research project funded by theFrench National Research Agency andinvolving the University of AgriculturalSciences, Bangalore, CIRAD (Centerfor International Cooperation on Agro-nomic Research and Development),the French Institute of Pondicherry,and the Kodagu Model Forest Trust.The aim of the project is to identify theconditions a GI must fulfill in order tohelp maintain and protect biologicaland cultural diversity.

AUTHORS

Claude GarciaCIRAD and French Institute ofPondicherry – FIP, 11 St Louis Street,PB 33, 605001 Pondicherry, [email protected]

Claude Garcia works in CIRAD’s For-est Resources and Public PoliciesResearch Unit. He is based at theFrench Institute of Pondicherry, wherehe is in charge of the Managing Biodi-versity in Mountain Landscapes project.

Delphine Marie-VivienCIRAD and National Law School of

Mountain Research and Development Vol 27 No 3 Aug 2007