B.I.C.€¦ · Exempted Services Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia Policy Options 2....

Transcript of B.I.C.€¦ · Exempted Services Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia Policy Options 2....

Review of Domestic Public Financing Sources

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

B.I.C.Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC

2019

Abebe Alebachew and

Workie Mitiku

January 2019

Financing Exempted Health Services in Ethiopia: Analysis of Potential Policy Options

Table of contentsII

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

Table of Contents

1. Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

2. Methodology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

3. Why Focus on Financing of Exempted Services? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

4. Review of Domestic Public Financing Sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

5. Review of Different Country Experiences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

6. Options for Future financing exempted services in Ethiopia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

7. Overall Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

8. References. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Suggested Citation:Alebachew, A., Mitiku, W. 2019. Financing Exempted Health Services in Ethiopia: Analysis of Potential Policy Options. Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Boston, Massachusetts.

Cover Photo by Alicia Harvey

Table of Tables

Table 1: Total cost of commodities for exempted services both at health center and primary hospital levels, 2015/16-2019/20, in ETB . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Table 2: Sources of domestic revenue/public finance, 2013/14 (Gregorian Calendar) . . . . . . . 4

Table 3: Types of tax in Ethiopia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Table 4: Estimated additional resources for health if government committed 10% of additional annual budget to health sector . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Table 5: Tax rates of comparable African countries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Table 6: Actual VAT collection and potential if there were increments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Table 7: Tax revenues on alcohol and tobacco products by type of tax in 2013/14, in . million birr. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Table 9: Potential revenue from airline Levy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

Table 10: Mobile subscribers and revenue generated in Ethiopia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Table 11: Comparison of the potential resource generation and coverage of the resource needed to cover exempted health services for the year 2015/16. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

1 Introduction

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

1. Introduction

A background paper on exempted health service was published in 20181. This paper estimated the financial requirement of the exempted health services offered at public primary health care facilities in Ethiopia based on estimated unit costs of such services and the targets set in the Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP). A fiscal space analysis at different government levels was conducted to determine the possibilities of financing exempted services within the current budgets of federal, regional and woreda governments. The report clearly indicated that financing exempted services, particularly their commodities, remains one of the major issues for the sustainability and success of Ethiopia’s equity-focused primary health care (PHC) policies. The amount of resources required for exempted service commodities is significant, not only as a percent of the current allocations for health, but also as a percent of the macroeconomic fiscal framework (MEFF) projections. With the projected decline in external financing for health, the sector needs to explore mechanisms and strategies to ensure domestic resources gradually take over the financing of exempted services in general and their commodities in particular. The previous report recommended that the sector needs to explore mechanisms and strategies for the long-term transition to gradually financing health in general and exempted services in particular through domestic resource mobilization and increased budget allocation to health.

This policy paper is a continuation of the background paper, and aims to explore the plausible options for increasing domestic resources to finance exempted health services, and provides recommendations according to the available options. This paper explores the experiences of other countries in financing health, and the feasibility of additional domestic sources – both through regular government allocation and innovative financing – for discussion and agreement by the stakeholders in the health sector.

More specifically this paper:

a) Provides trends and sources of the current financing mechanisms, their strengths and weaknesses under the current list of exempted services; as well as sustainability visions/strategies of continuing to finance these services given the likely decline in funding from partners;

b) Explores options available to finance exempted health services, particularly the drugs and supplies cost components, in line with the National Health Care Financing Strategy and based on the estimated costs of exempted services and fiscal space analysis conducted for different levels of government (federal, regional, and woreda levels) in the background paper;2

c) Recommends appropriate option(s) for the government to sustainably finance exempted health services through increased domestic resources according to the country’s second Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP2) (2015/16-2019/2020) strategies based on a macroeconomic framework; and

d) Serves as an input for the development of a strategy for sustainable financing of exempted services.

1 Alebachew, A; Mitiku, W; Mann, C; and Berman, P. (2018). Exempted Health Services in Ethiopia: Cost Estimates and its Financing Challenges. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC. Boston, Massachusetts and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

2 The options are mainly in terms of increasing domestic resource mobilization (DRM) for health through introduction of innovative financing mechanism as there is limited fiscal space to finance exempted health services with the current share of health to national budget and the limited fiscal space at different levels of government particularly at woreda level.

2 Methodology & Why Focus on Exempted Services?

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

2. Methodology

The experience of other countries in financing health in general and innovative financing in particular was reviewed. The authors also used data from Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation (MOFEC) on the sources of domestic public finance/government fiscal data and reviewed relevant proclamation on taxes, literatures on domestic resource mobilization and country experiences to finance public health. In addition, secondary data was used to analyze the current financing of exempted health services. The paper used the background paper on exempted health services, which covers estimation of costs of exempted health services for the HSTP period, and fiscal space analysis at different levels of government, as an input to compare costs and potential mobilization for the different possible options of financing exempted services. Consultations were made with the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (MOH) and other stakeholders on the options for financing as well as the recommendations of the viable options of financing exempted health services with domestic resources.

3. Why Focus on Financing of Exempted Services?

Mobilization of resources for exempted health services is one of the agendas of the Ethiopian government, given the declining trend of donor financing in general, and for such services in particular. To this effect, the cost of the exempted services were previously estimated in Ethiopia based on the unit costs of such services at primary health care level (health centers and primary hospitals)3. The study estimated commodity costs of exempted health services based on the targets of population coverage set in HSTP for the HSTP period (2015/16 to 2019/2020). As stated in the table 1, Ethiopia needs about 5.6-7.6 billion ETB per annum, or a total of 33.3 billion ETB , to cover the cost of drugs and supplies for exempted health services during the HSTP period. Of this, the cost of drugs and supplies for family planning takes the lion share (63%) followed by delivery and ART treatment, each constituting about 10%, while immunizations account for only 8% of the total cost. The cost of commodities for each type of exempted health services is presented in the Table 1 below.

3 Alebachew, A; Mitiku, W; Mann, C; and Berman, P. (2018). Exempted Health Services in Ethiopia: Cost Estimates and its Financing Challenges. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC. Boston, Massachusetts and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

Table 1: Total cost of commodities for exempted services both at health center and primary hospital levels, 2015/16-2019/20, in ETB

Type of

Exempted Service

Total Cost Grand Total

% share2015/16 2016/2017 2017/18 2018/19 2019/2020

1 EPI

Pentavalent (DPT-HepB-HIB)

207,979,948 219,355,787 221,664,795 228,429,441 235,091,592 1,112,521,562 3.3

Pneumococcal 168,407,521 182,101,583 190,571,424 200,841,321 211,189,360 953,111,210 2.8

Rotavirus 24,067,863 50,234,189 76,673,236 103,815,304 131,847,702

386,638,294

1.1

Measles 31,489,536 33,584,563 33,945,687 34,620,988 35,642,314

169,283,087

0.5

BCG 17,219,489 18,161,340 18,352,512 18,912,584 19,464,170

92,110,096

0.3

2 Family Planning 3,533,194,323 4,041,114,935 4,363,213,874 4,682,811,253 5,016,471,324 21,636,805,709 64.2

3 Antenatal Care 31,827,536 34,698,993 37,643,720 40,650,966 43,710,195

188,531,409 0.6

4 Delivery 565,599,348 630,641,537 697,575,866 766,180,301 836,228,346 3,496,225,398 10.4

5 Postnatal Care 37,303,654 38,546,324 39,785,501 41,013,285 42,223,193

198,871,958 0.6

6Tuberculosis

Treatment 224,980,973 235,770,156 246,677,008 257,646,565 268,630,527 1,233,705,228 3.7

7Anti-Retroviral

Therapy (Adults)

548,673,788 575,339,379 604,921,404 628,549,845 649,136,309 3,006,620,725 8.9

Anti-Retroviral Therapy

(Children) 69,144,636 77,377,289 82,205,825 83,992,384 88,651,921

401,372,055

1.2

8Malaria

Treatment 201,214,140 189,987,600 167,102,730 142,922,490 117,446,880

818,673,840

2.4

Total Cost 5,661,102,754 6,326,913,674 6,780,333,583 7,230,386,726 7,695,733,833 33,694,470,572 100

4 Review of Domestic Public Financing Sources

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

4. Review of Domestic Public Financing Sources

The current sources of domestic public finance in Ethiopia are categorized as tax revenue and non-tax revenue. As shown in Table 2, in 2013/14 total domestic revenue constituted about 70% of the total resources available. Tax revenue constituted about 62% of the total resources and non-tax revenue constituted the remaining 8% of the total resources in 2013/14.

Table 2: Sources of domestic revenue/public finance, 2013/14 (Gregorian Calendar)

Sources of Revenue Amount in ETB (millions) Share in %

Tax Revenue 123,179.35 62%

Non-Tax Revenue 16,498.35 8%

Total Domestic Revenue 139,677.71 70%

External Assistance and loan including PBS 59,534.62 30%

Total Resources 199,212.32 100%

Source4

Total domestic revenue constitutes 70% of the total resources available to the country and the remaining 30% were covered from external loan and assistance and finances including from of promoting of basic services (PBS), which account for 24% of external loan and assistance and 7% of the total resources.

However, tax to GDP ratio in Ethiopia is less than 13%, which is below the Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) average of about 15%, as well as below the 18% ratio in Kenya and 15.8% in Tanzania.

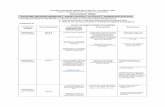

As indicated in the Table 3 below, in Ethiopia, there are three main types of taxes, namely:

1. Income and profit tax (direct taxes);

2. Taxes on good and services (indirect taxes) and

3. Foreign trade taxes.

The direct taxes include personal income tax, rental income, profits to individuals, business profit tax, agricultural income tax, tax on dividend and chance winning, capital gain tax, royalties, withholding tax on imports, interest income tax, chat income, rural land use fee, and urban land lease. On the other hand, the indirect tax includes value added tax (VAT) on goods, VAT on services, excise tax on locally manufactured goods, sales tax on goods, service taxes and stamp sales duty. Foreign trade taxes include custom duty, excise tax on imports and sales tax on imports.

Non-tax revenue includes charges and fees, sales of goods and services, government investment, capital revenue and municipal revenue.

Of the total tax revenue during the 2013/14 year, direct taxes and foreign trade taxes each accounted for about 36% of the total tax revenue (together totaling 72% of the total tax revenue) while indirect tax accounts for the remaining 28%.

4 MOFEC. (2015). Sources of Domestic Revenue, EFY 2007. Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

5 Review of Domestic Public Financing Sources

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

Table 3: Types of tax in Ethiopia

Types of Tax Components in Each Type of Tax

Direct tax (income and profit tax)

Personal income tax

Rental income,

Profits to individuals

Business profit tax

Agricultural income tax

Tax on dividend

Chance winning

Capital gain tax

Royalties,

Withholding tax on imports

Interest income tax,

Chat income

Rural land use fee

Urban land lease

Indirect tax (taxes on goods and services)

Value added tax (VAT) on goods

VAT on Services,

Excise tax on locally manufactured goods

Sales tax on goods

Service taxes

Stamp sales duty

Foreign trade tax

Custom duty

Excise tax on imports

Sales tax on imports

With regard to sharing of tax revenues collected at regional state levels, tax revenues collected at the regional state levels from personal income tax, turnover tax (applicable for business falling below the VAT registration threshold in terms of annual sales value), agricultural tax, rural land use fee and “chat” tax are not shared to the federal government, while tax revenue collected from profit tax, VAT and excise tax are shared to the federal government. Accordingly, of the 123.18 billion Ethiopian birr (ETB) tax collected in 2013/14, the share of revenue to the federal state was about 76%, while the remaining 24% was to the regional states. This indicates that the regional states have a limited capacity to finance their expenditure, including basic services, with their tax revenue. The main sources of revenue for regional states that complements their tax revenues are block grants from the federal government. The regional states, with the exception of Addis Ababa, could only finance 23.9% of their expenditure from their tax revenue for the year 2015/165. While in absolute terms the federal transfers to regions has increased significantly over the years, the share of federal transfers to regional states relative to federal tax revenue and federal expenditure is, on average, declining.6 The share of transfers from the federal government to regions in the form of block grants constituted 45% of the federal tax revenue in 2013/14. This share was higher in the preceding years, which reached 73% in 1997/987. The revenue assignment to regions do not allow them to generate resources to finance all of their spending needs and has forced them to depend on federal transfers.8 Channel 2 and project-based assistance are also other additional sources of finances for regions.

5 Alemu, G., Nuru, S., G/Tsadique, G. (2017). Domestic Resource Mobilization in Ethiopia: Prospects and Challenges. Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation; Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 6 Ibid7 Ibid8 Ibid

6 Review of Domestic Public Financing Sources

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

A recent study on tax performance in Ethiopia concluded that although the economy has been growing fast, with double digit GDP growth for more than a decade, tax performance, as measured by tax to GDP ratio, has been low with minimal growth; never exceeding 13.3% of GDP. The low performance of tax to GDP ratio in Ethiopia is significant when compared with other African countries. The tax to GDP ratio was 18.3% in Kenya, 15.8% in Tanzania, and 15.8% for SSA on average in 2010, while it was only 12.7% in Ethiopia. Tax buoyancy (tax buoyancy is tax responsiveness to economic growth. Optimal tax theories expect that as the tax base/economy grows tax revenue also grows a rate faster than the economy/base) was found to be weak, as it grew at a lower rate than its base/the economy, signaling poor performance of the tax system. This poor performance of the tax responsiveness to economic growth could be explained by the structure of the economy, which is dominated by agriculture, where it is more difficult to collect revenue compared to economies dominated by other sectors such as manufacturing.

Unfortunately, the provision of exempted services – identified health care services offered for free to the whole population – are established by the regional proclamations in regions where health finance reforms are implemented- which makes regions fiscally responsible. As documented in the exempted service financing background paper, the federal government has been able to mobilize resources for commodities of exempted services from external aid: Immunizations have been provided by the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI); HIV/AIDS, Malaria and TB commodities have been supported by the Global Fund PEPFAR/USAID; and family planning commodities have been supported mainly by DFID and other partners.9 However, the external financing has started to decline, and gains made through the expansion of exempted services are going to suffer in the coming years unless strategic actions are taken. There is thus a need to look for alternative sources of financing to ensure that the gains made so far are sustained. The options below assume that the Ethiopian government will continue to provide these services free of change in the near future and will not opt for financing them through user fees. If this is the preferred option, the analysis would then lead to costing and setting fees for commodities.

The following sections outline the best experiences of other countries and the options available for Ethiopia.

9 Alebachew, A; Mitiku, W; Mann, C; and Berman, P. (2018). Exempted Health Services in Ethiopia: Cost Estimates and its Financing Challenges. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC. Boston, Massachusetts and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

7 Review of Different Country Experiences

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

5. Review of Different Country Experiences

In an effort to mobilize additional finances for the health sector, countries have pursued different mechanisms. In this regard, taxing unhealthy products (sin taxes) like tobacco, alcohol, salt, and sugar, is considered to play a ‘triple win’ game as it has a potential to discourage unhealthy consumption, reduce the need for expensive treatment in the future and mobilize resources for the sector.10 Countries such as Thailand and the Philippines have dedicated earmarked sin tax to address specific public health problems. For example, Thailand has levied an additional 2% surcharge on tobacco and alcohol earmarked for the health promotion fund. The main activities using the fund are broad based civil society campaigns tackling tobacco, traffic accidents, alcohol, healthy life style, active living and obesity, sexuality and HIV/AIDs prevention.11 The Addis Ababa Commitment during the Third International Conference on Financing for Development stated they ‘recognize, in particular, that, as part of a comprehensive strategy of prevention and control, price and tax measures on tobacco can be an effective and important means to reduce tobacco consumption and health-care costs, and represent a revenue stream for financing for development in many countries’.12

Similarly, the Philippines’ tax increase on tobacco and alcohol products in December 2012 enabled them to generate additional funding to enroll more people in universal health care (UHC) and scale-up non-communicable disease (NCD) prevention services in primary care. The increased taxes enabled the government to raise more than US$1.2 billion in the first year and allowed them to enroll more people in UHC. Revenues from the taxes on tobacco and alcohol in the Philippines are earmarked for specific programs. About 15% of the tax revenue is allocated to help tobacco farmers and workers find alternative livelihoods, and the remaining 85% is channeled to fund universal health care, upgrade medical facilities and train health professionals.13 Such country experiences indicate that earmark taxes dedicated to health discourages the use of such products that are hazardous to health and at the same time promotes the provision and promotion of services that prohibit the use of such products. These taxes are usually indirect taxes, and of the indirect taxes focusing on goods and services that are either luxuries or hazardous to health or basic good, which are demand inelastic.

Based on such country experiences, the option of financing exempted health services, in particular the cost of drugs and supplies, from the tax generated from alcohol and tobacco was considered and assessed below in section 6, based on the actual revenue generated from such sources in Ethiopia.

Airline levy typically consists of a small tax (commonly US$1-2 for economy class passengers and US$10 for business class passengers) that is added to the price of outbound airplane tickets. In 2006, France became the first country to implement an airline levy. The tax is intended to generate a stable and predictable source of revenue for supporting developing countries in their efforts to achieve their development goals. In Africa, countries that have implemented the tax commonly use the revenue generated to fund HIV responses. More than 30 countries have introduced an airline levy. In Africa, the following countries have implemented airline levies: Benin; Burkina Faso; Cameroon; Central African Republic; Democratic Republic of the Congo; Cote d’Ivoire; Gabon; Guinea; Liberia; Madagascar; Mali; Mauritius; Morocco; Namibia; Niger; Sao Tome and Principe; Senegal; South Africa and Togo. Other African countries considering a similar mechanism include Chad, Kenya, Mozambique and Nigeria. Outside of Africa, Brazil, Chile, Cyprus, France, Luxembourg, Norway, Republic of South Korea, Spain and United Kingdom also implemented the levy.14

10 The Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatom House. (2014). Shared Responsibilities for Health - A Coherent Global Framework for Health Financing; Final Report of the Centre for Global Health Security Working Group on Health Financing. London, UK.11 Srithamrongsawat, S. et al. (2010). Funding Health Promotion and Prevention - The Thai Experience. World Health Report (2010) Background paper, No. 45. Geneva, Switzerland.12 UN (2015). Outcome Document of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development: Addis Ababa Action Agenda. The Third International Conference on Financing for Development. A/CONF.227/L.1. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/sites/www.un.org.africarenewal/files/N1521991.pdf 13 WHO (2015). “Sin Tax” expands health coverage in Phillippines. https://www.who.int/features/2015/ncd-philippines/en/ 14 The Global Fund. (2016). Innovative and Domestic Financing for Health in Africa: Documenting Good Practices and Lessons Learnt.

8 Options for Future Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

Following the adoption of the levy through domestic legislation, airlines are instructed to collect and declare funds generated from the tax. The tax is applied to passengers when they purchase their tickets (as a component of all applicable airport taxes). It is levied on all passenger flights originating from countries that impose it. The generated revenue is then transferred to the national treasury, usually through the Ministry of Transport or the Civil Aviation Authority. Airline levy is considered to be economically neutral, equitable and transparent. Evidence so far documented that it (1) has no negative effect on air traffic, airline jobs or profitability; (2) is administratively simple and cost effective; and (3) has a positive reception among passengers and tax payers – the levy is a relatively small amount and therefore it is not felt by the clients.15

A study carried out by Nakhimovsky and et al from the Health Finance and Governance project by Abt Associates Inc. reviewed 19 types of domestic innovative financing mechanisms using four assessment criteria: 1) effectiveness and sustainability; 2) governance and efficiency; 3) progressivity; and 4) macro-economic impact. The only mechanism that was found to positively meet all four criteria was airline levy, while financial transaction tax is positive on three of the criteria, but has no impact on governance and efficiency. Mechanisms that meet all criteria but first one include voluntary corporate social responsibility, loan conversion and lotteries.16

6. Options for Future Financing of Exempted Services in Ethiopia

There are different options for introducing innovative financing including but not limited to:

i. Special levy on large profitable companies;

ii. Levy on currency transactions,

iii. Diaspora bonds;

iv. Financial transaction tax;

v. Mobile phone voluntary solidarity contribution;

vi. Tobacco and alcohol excise tax,

vii. Excise tax on unhealthy food,

viii. Selling franchise products/services; and

ix. Introducing tourism tax.

While some of these were explored above as options, the last three are not explored as their relevance in terms of generating adequate resources is questionable in the Ethiopian context.

6.1. Increasing government allocation to health

As outlined in the preceding sections, the need to increase government allocation to health to ensure that it meets its primary health care led UHC agenda is paramount, especially within the current environment of declining external aid. The challenges of collecting revenue in the country are also recognized, as well as the limited fiscal space, especially at regional and woreda levels. The major potential that is available in increasing budget allocation is using the federal revenue and expenditure assignment.

Geneva, Switzerland. Available at https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/32895-file-lessons_learnt_health_financing_in_africa.pdf 15 The Global Fund. (2016). Innovative and Domestic Financing for Health in Africa: Documenting Good Practices and Lessons Learnt. Geneva, Switzerland. https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/32895-file-lessons_learnt_health_financing_in_africa.pdf16 Nakhimovsky, S., Langenbrunner, J., White, J., Vogus, A., Zelelew, H., Avila, C. (2014). Domestic Innovative Financing for Health:

Learning from Country Experience. Health Finance & Governance Project, Abt Associates Inc. Bethesda, MD.

9 Options for Future Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

One option for increasing government allocation uses the best examples of Brazil and Vietnam. These countries set percentage shares for health from the total government budget -- the growth of budget allocation for health should not be less than the growth of the total budget. Ethiopia could commit to allocate at least 10% of the additional federal budget for health in each year until the commodity costs of exempted services are covered. With this option, there is a potential to mobilize about ETB 32.3 billion additional funding using the Medium Term Economic and Financing Framework projections as shown in Table 4. If 50% of the additional allocation estimated above is used to finance exempted commodities, it will finance about 50% of the required cost.

Table 4: Estimated additional resources for health if government committed 10% of additional annual budget to health sector

Year

Total Projected Domestic

Resources (in Billion ETB)

Total Additional Projected Revenue

Current Allocation

(8%)

Commitment to Allocate 10% of Additional Government Resources

Total Allocation

Share of Health in

Total Govt. Spending

2017 216.4 17.312

2018 221.2 4.8 17.696

2019 286.3 65.1 22.904 6.51 29.414 10%

2020 352.5 66.2 28.2 6.62 34.82 10%

2021 437.2 84.7 34.976 8.47 43.446 10%

2022 544.8 107.6 43.584 10.76 54.344 10%

Total 129.664 32.36 162.024

Source17

Another option is for government to earmark a certain percentage of the value added tax (VAT) to health. Ghana and other countries have such experience. The MOFEC resource mobilization study clearly shows that of African countries, only Egypt and South Africa have VAT lower than Ethiopia (14%) and only Ghana and Namibia have a VAT equal to Ethiopia (15%) while the remaining 12 countries included in the study have higher VAT rates (from 16-19%).18 The following table below shows tax rates in comparable African countries.

Table 5: Tax rates of comparable African countries

VAT (%) Excise Tax (%)Custom Duty Rate (%)

Custom Duty Rate Average Duty

RateEthiopia 15 10-100 0-35 16.67

Kenya 16 10 and fixed amount 0-100 25

Rwanda 18 10-70 0-100 25

Tanzania 18 5-120 0-100 25

Uganda 18 0-160 0-100 25

Source19

17 Alebachew, A; Mitiku, W; Mann, C; and Berman, P. (2018). Exempted Health Services in Ethiopia: Cost Estimates and its Financing Challenges. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC. Boston, Massachusetts and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.18 Alemu, G., Nuru, S., G/Tsadique, G. (2017). Domestic Resource Mobilization in Ethiopia: Prospects and Challenges. Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation; Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 19 Ibid.

10 Options for Future Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

In addition, the study shows that there are a lot of exemptions in Ethiopia.20 The Ethiopian VAT has provided about 17 types of exemptions from VAT, which undermines its potential to generate revenue. Had Ethiopia increased the VAT rate from the current rate of 15% to 16% or 17%, to become closer to Rwanda and Tanzania’s rates, it would have been able to mobilize an additional ETB 17.5 billion or ETB 35 billion respectively in collections between 2010/11 to 2015/16, as shown in Table 6. Please note that more than 50% of this difference would have been generated only in the last two years, showing the existence of huge potential collection from 2018 forward. If there is a decision to increase VAT to 16-19%, and this is channeled to the health sector, this would significantly reduce the dependence on external aid, as shown in table 6. If VAT increased to 16%, it will finance 50% of the commodity costs in 2014/15 and 2015/16. If it increased to 17%, it will finance the full commodity costs per year in the two years.

Table 6: Actual VAT collection and potential if there were increments

VAT/GDP Rate (%)

Actual Collection Million ETB

Total Potential Collections Two Options, Million ETB

Additional Potential Collections, Two Options,

Million ETB

16% 17% 16% 17%

2010/11 5.3 22,909.50 24,436.80 25,964.10 1,527.30 3,054.60

2011/12 3.83 28,247.43 30,130.59 32,013.75 1,883.16 3,766.32

2012/13 3.98 35,086.39 37,425.48 39,764.58 2,339.09 4,678.19

2013/14 4.01 42,585.73 45,424.78 48,263.83 2,839.05 5,678.10

2014/15 4.97 64,515.01 68,816.01 73,117.01 4,301.00 8,602.00

2015/16 4.55 69,559.00 74,196.27 78,833.53 4,637.27 9,274.53

Total 262,903.06 280,429.93 297,956.80 17,526.87 35,053.74

Source21

6.2. Taxing tobacco and alcohol

Different types of taxes are applicable on tobacco and alcohol in the country. These include VAT, excise tax on locally manufactured good, sales tax on goods, custom duty, excise tax on imports and sales tax on imports.

Currently, the excise tax on alcohol ranges from 50-100%, while that of tobacco and tobacco products ranges from 20-70%.22 On the other hand, the VAT is 15% like for all other goods and services. The revenue generated from the taxes on alcohol and tobacco products by type of taxes in 2013/14 is depicted in Table 7.

As shown in the following table, tax revenue from both alcohol and tobacco products is 1.22 billion ETB, and of this 46% was generated from alcohol and alcohol products while the remaining 54% was from tobacco and tobacco products. The amount of resources generated (1.22 billion ETB) from alcohol and tobacco taxes was 21.5% of the required financing to cover commodity costs of exempted health services in 2015/16. With regard to the type of tax, excise tax on locally produced tobacco and alcohol products constituted a little more than half (52%) of the total tax revenue generated from these goods.

20 Alemu, G., Nuru, S., G/Tsadique, G. (2017). Domestic Resource Mobilization in Ethiopia: Prospects and Challenges. Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation; Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 21 Ibid.22 Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. (2002). Excise Tax Proclamation No. 307/2002, December 21, 2002. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

11 Options for Future Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

Table 7: Tax revenues on alcohol and tobacco products by type of tax in 2013/14, in million birr

Alcohol and Alcohol Products

Tobacco and Tobacco Products

Total

VAT 95.18 87.36 182.54

Excise tax on locally produced products

262 378 640

Sales tax 5.36 0 5.36

Custom duty 47 39 86

Excise tax on imports 116.65 66.82 183.47

Sales tax on imports 42.89 87.39 130.28

Total 569.08 658.57 1,227.65

Source23

6.3. Levy on airline passengers

According to the information generated by the World Bank from the International Civil Aviation Organization, Ethiopian airline passengers increased from 4.4 million in 2011 to 9.6 million in 2017 showing an annual average growth rate of 14% per year.

Table 8: Trends of Ethiopian Airlines passengers and annual growth rates

Actual Passengers

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Numbers of passengers

4,440,918 5,001,122 5,671,501 6,274,582 7,074,779 8,242,114 9,566,378

Growth rate 0.13 0.13 0.11 0.13 0.16 0.16

Average annual growth rate

0.14

Source24

Assuming that the average annual growth rate continues to 2020, and assuming that 80% of these passengers are international while 20% are domestic, the potential revenue to be collected from airline levy is presented in Table 9. Taking the best practice of levying $5 for international passengers and $1 for domestic ones, the potential estimated revenue ranges from USD $46 million in 2018 to USD $59.5 million in 2020. If business class passengers are taxed $10, the revenue is likely to increase. This revenue however, can only finance 23% of the required total commodity costs of exempted services per year. As stated in the preceding section, the international evidence shows that this will not affect profitability and competitiveness of the airline, nor would it negatively affect passengers.

23 MOFEC. (2015). Tax Revenues on Alcohol and Tobacco. Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.24 World Bank. (2017). Air transport, passengers carried. International Civil Aviation Organization, Civil Aviation Statistics of the World and ICAO staff estimates. https://data.worldbank.org/

12 Options for Future Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

Table 9: Potential revenue from airline levy

Ass

umpt

ions Number of Passengers Potential Collections in USD

2018 2019 2020

Levy Tax ($) per Passe- nger

2018 2019 2020

Domesticpassengers

20% 2,181,134 2,486,493 2,834,602 1 2,181,134 2,486,493 2,834,602

Internationalpassengers

80% 8,724,537 9,945,972 11,338,408 5 43,622,684 49,729,859 56,692,040

Total 100% 10,907,689 12,434,484 14,175,030 45,805,836 52,218,371 59,528,662

6.1. Taxing mobile phones

With growing connectivity and use of mobile phones, taxing mobile phone service is considered as one of the promising potential sources of financing in many countries. The number of mobile subscribers and the revenue generated from it in Ethiopia has been increasing over the years, as can be seen from the table below.

Table 10: Mobile subscribers and revenue generated in Ethiopia

Mobile Subscribers (in Million)

Revenue Generated (Million ETB)

Estimated Revenue per Individual per

Annum

Estimated 2% Tax Revenue

2011/12 20.53 12,770 622.02 255

2012/13 25.62 16,644 649.65 333

2013/14 30.94 17,358 561.02 347

2014/15 42.31 21,500 508.15 430

2015/16 51.22 28,372 553.92 567

2016/17 62.62 33,343 532.47 667

Source25

Ethiopian telecom, the monopoly provider, experiences a growth in revenue of 22% on average over the last five years. Recently, however, the government recognized the need to reduce unit prices, and reduced the unit price by as much as 44% over three months. It is also working towards liberalizing the telecom sector. With the reforms on the agenda, it may be difficult to start using tax on mobile service as a potential for resource mobilization for health, and it might also have a negative effect on growth of the sector.

6.2. Remittance tax

One of the major sources of foreign currency in Ethiopia is the remittance obtained from the diaspora living outside of the country. A report by the IMF clearly documented that remittances in Ethiopia are highly significant, accounting for about 5.5% of GDP in 2016/17 - well exceeding the exports of goods (3.6 percent of GDP).26

Recent estimates show that the country received USD 1.8 billion in 2015 and about USD 4 billion in 2017 from remittances.

25 World Bank (2017). Mobile Cellular Subscriptions. International Telecommunication Union, World Telecommunication/ICT Develop-ment Report and database. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.CEL.SETS?locations=ET.26 IMF (2018). Staff Report for the 2017 Article 4 Consultation - Press Release. Staff Report and Statement by the Executive Director for the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. IMF country report 18/18. International Monetary Fund. Washington, D.C.

13 Overall Recommendations

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

In 2018 the government established a diaspora fund with a management board in order to mobilize funding from the diaspora (a dollar a day), and plan to utilize the funds on identified government priorities. One of the priorities being mentioned is health services. Given that this is at the initial stage at the moment, it is difficult to recommend using it as another source of innovative financing. A further exploration of the possibility of mobilizing additional diaspora funding for health through the newly created modality, or through a separate ‘diaspora health fund’, and its additionality will be warranted when innovative financing options are considered by the government.

7. Overall Recommendations

As outlined above, there are several options that Ethiopia can explore to further assess the feasibility of mobilization of domestic revenue for health, with engagement and leadership of MOFEC and the planning commission. Of the options outlined, allocation of 10% of the additional government revenue to the health sector per annum, or increasing VAT to 16%, would mostly finance commodity cost of exempted health services. Channeling of the existing revenue from tobacco and alcohol taxes to health can each raise about ETB 1.2 billion per annum, which can be allocated to cover part of the cost of exempted health services. The table below summarizes the potential resources that can be generated from various sources and the resources needed to cover commodity cost of exempted health services.

Table 11: Comparison of the potential resource generation and coverage of the resource needed to cover exempted health services for the year 2015/16.

Source of Potential RevenueAmount of Potential

Resource Generation (billion ETB)

% Coverage of the Resource Needed

Allocation of 10% of additional annual government revenue to the health sector

6.5 116%

Increase VAT from 15 % to 16% 4.6 82%

Channeling tax revenue on tobacco and alcohol to health sector

1.22 21.7%

Airline levy 1.28 23%

Mobile phone tax 0.66 11.8%

These summary options could be presented in the ‘Policy Dialogue’ session of the health care financing capacity building planned in the next three months as part of the FMOH plan to engage stakeholders on the revised health financing strategy-being prepared as part of the World bank’s support. The high level government authorities need to have a common understanding on the way forward, as it will help them develop strategies on how to organize themselves and start working towards ensuring Ethiopia is moving towards self-financing of exempted services in the long term. The next steps therefore are:

i. Establish a multi-sector working group to further explore the feasibility of the above and additional options;

ii. Design the feasibility and management mechanisms of the agreed financing mechanisms and

iii. Endorse them for implementation.

MOH and partners that work around health financing need to be prepared to provide guidance and technical assistance, including lessons from other countries, to support the policy making process.

14 References

Financing Exempted Services in Ethiopia - Policy Options

8. References

Alebachew, A; Mitiku, W; Mann, C; and Berman, P. (2018). Exempted Health Services in Ethiopia: Cost Estimates and its Financing Challenges. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC. Boston, Massachusetts and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Alemu, G., Nuru, S., G/Tsadique, G. (2017). Domestic Resource Mobilization in Ethiopia: Prospects and Challenges. Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation; Breakthrough International Consultancy PLC. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. (2002). Excise Tax Proclamation No. 307/2002, December 21, 2002. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

The Global Fund (2016). Innovative and Domestic Financing for Health in Africa: Documenting Good Practices and Lessons Learnt. Geneva, Switzerland. https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/32895-file-lessons_ learnt_health_financing_in_africa.pdf

IMF (2018). Staff Report for the 2017 Article 4 Consultation - Press Release. Staff Report and Statement by

Executive Director for the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. IMF country report 18/18. International Monetary Fund. Washington, D.C.

MOFEC (2017). Government Revenue Data. Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

MOFEC (2015). Sources of Domestic Revenue, EFY 2007. Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

MOFEC (2015). Tax Revenues on Alcohol and Tobacco. Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Nakhimovsky, S., Langenbrunner, J., White, J., Vogus, A., Zelelew, H., Avila, C. (2014). Domestic Innovative Financing for Health: Learning from Country Experience. Health Finance & Governance Project, Abt Associates Inc. Bethesda, MD.

The Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatom House. (2014). Shared Responsibilities for Health - A Coherent Global Framework for Health Financing; Final Report of the Centre for Global Health Security Working Group on Health Financing. London, UK.

Samrit Srithamrongsawat, etal. (2010). Funding Health Promotion and Prevention - The Thai Experience. World Health Report (2010) Background paper, No. 45. Geneva, Switzerland.

UN (2015). Outcome Document of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development: Addis Ababa Action Agenda. The Third International Conference on Financing for Development. A/CONF.227/L.1. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/sites/www.un.org. africarenewal/files/N1521991.pdf

UN (2015). Public Health Taxes. Paper Presented on the Third International Conference on Financing for Development: Addis Ababa Action Agenda; International Conference for financing Development. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

World Bank (2017). Air transport, passengers carried. International Civil Aviation Organization, Civil Aviation Statistics of the World and ICAO staff estimates. https://data.worldbank.org/

World Bank (2017). Mobile Cellular Subscriptions. International Telecommunication Union, World Telecommunication/ICT Development Report and database. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.CEL. SETS?locations=ET.

WHO (2015). “Sin Tax” expands health coverage in Phillippines. https://www.who.int/features/2015/ncd-philippines/en/