BGAS - Norborne Berkeley’s monument to the Horatii and Curiatii · 2016. 3. 23. · 222 WILLIAM...

Transcript of BGAS - Norborne Berkeley’s monument to the Horatii and Curiatii · 2016. 3. 23. · 222 WILLIAM...

-

Norborne Berkeley’s monument to the Horatii and Curiatii

By WILLIAM EVANS

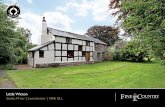

Norborne Berkeley, later Lord Botetourt, MP for Gloucestershire 1741–63, inherited the family estate at Stoke Gifford. Over some 20 years, and with the help of the gentleman architect Thomas Wright, Berkeley refashioned the estate’s mansion and laid out a landscaped park south of the house.1 The works in the park included the construction of several masonry features, one of which was an approximate replica of the ruinous remains of a structure at Albano Laziale, south-east of Rome, known to travellers as the tomb of the Horatii and Curiatii. The location of the structure is marked no. 17 in Fig. 1. A reconstruction by James Russell, based on John Hunt’s 2008 excavation of the site, is Fig. 2. Hardly any trace of the structure at Stoke Park is now visible. The purpose of this note is to describe the structure erected by Berkeley and that on which it was modelled, and to explore the history of both.

In November 1761 Berkeley was ‘helping the carpenters to raise the broken Temple in the Park’.2 Berkeley may well have seen the original on his grand tour in 1737, when he was at Rome: the Blathwayt boys of Dyrham Park had seen it in 1707.3 How it looked in the 18th century can be seen from Richard Wilson’s painting, now in Gloucester museum, but not on open display;4 Giovanni Battista Busiri’s painting for the Wyndhams at Felbrigg in Norfolk; a drawing, attributed to Robert Adam, now in Sir John Soane’s Museum;5 and a print by Elisha Kirkall, now in the British Museum.6 Turner’s effort is in Tate Britain;7 Piranesi’s in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.8 Nowadays the structure stands where the Borgo Garibaldi leaves the course of the ancient Via Appia.9 It has a tall 15 m-square concrete base faced with peperino, a brown-grey volcanic tufa peppered with grains of black basalt. On each of the four corners of the base stands

1. For accounts of the landscaping and its historic significance, see J. Russell, ‘The archaeology of Stoke Park, Bristol’, Bristol and Avon Archaeol. 8 (1989), 30–40; T. Mowl, ‘The castle of Boncoeur and the Wizard of Durham’, The Georgian Group Jnl. 2 (1992), 32–9; D. Lambert and S. Harding, ‘Thomas Wright at Stoke Park’, Garden Hist. 17(1) (1989) , 69–82; D. Etheridge, ‘Monuments in Stoke Park’, Avon Gardens Trust Newsletter (2004), 27–38, and (2005), 9–19; M. Batey and D. Lambert, The English Garden Tour: a view into the past (London, 1990), 200–3; J. Hunt and J. Russell, ‘The tomb of the Horatii at Stoke Park’, Avon Gardens Trust Jnl. 9 (2009), 29–34.

2. Glos. Archives (GA), D 2700/QP 3/6/6, b. 7 (Stoke accounts).3. de Blainville to Blathwayt, 14 May 1707: N. Hardwick (tr. and ed.), The Grand Tour of William and John

Blathwayt of Dyrham Park 1705–1708 (Saltford, 1981), 93.4. Glouc. Mus. Service Art Colln., GLRCM: Art 00307.5. Sir John Soane’s Mus., Adam, vol. 57/130.6. Brit. Mus., print 1874,0808.993.7. Tate Brit., D36420 Turner Bequest CCCLXXIII 7.8. Metropolitan Mus. of Art, Accession 41.71.1.11(8).9. Photos of the structure can be seen at http://www.museicivicialbano.it/sepolcro_detto_degli_orazi_

e_curiazi.html; http://www.geoplan.it/luoghi-interesse-italia/monumenti-provincia-roma/cartina-monumenti-albano-laziale/monumenti-albano-laziale-sepolcro-degli-orazi-e-curiazi.htm; and http://www.flickr.com/photos/dealvariis/sets/72157619245135474/.

Trans. Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 131 (2013), 221–228

221-228_BGAS131_Evans.indd 221 22/01/2014 15:28

-

222 WILLIAM EVANS

Fig.

1.

Stok

e P

ark,

Sto

ke G

iffor

d, in

176

8 (B

erke

ley

died

in 1

770)

, dra

wn

by J

ames

Rus

sell.

The

loca

tion

of th

e m

onum

ent t

o th

e H

orat

ii an

d C

uria

tii is

num

bere

d 17

.

221-228_BGAS131_Evans.indd 222 22/01/2014 15:28

-

MONuMENT TO THE HORATII AND CuRIATII 223

Fig. 2. James Russell’s reconstruction sketch of the monument to the Horatii and Curiatii, looking north. Pococke mentioned only ‘four round Obelisks’.

221-228_BGAS131_Evans.indd 223 22/01/2014 15:28

-

224 WILLIAM EVANS

a truncated cone, also made out of blocks of peperino. Between them rises a fifth stump, above the tomb chamber whose masonry has allowed archaeologists to date the structure to the late republican period.10

There is no other existing structure in Italy like it, but there are representations of similar-shaped tombs on Etruscan urns of the Hellenistic period.11 The elder Pliny mentions a similar structure: in a passage about labyrinths he contemptuously quotes Varro’s description of the tomb of the Etruscan king Porsena at Clusium (modern Chiusi in Tuscany), the 300 ft-square base of which contained a labyrinth. Above the base, according to Varro, were five pyramids 150 ft high, which supported a bronze globe, which in turn carried a dish from which dangled bells: a huge monumental wind-chime.12 Modern archaeologists point out that the Albano structure stands near the site of a battle in 506 BC between the Etruscans and the Arricians in which, according to legend, Porsena’s son Arunte was killed.13 There is evidence from an inscription that there was a family at Albano called the Aruntii.14 It is suggested that the Albano structure may have been the Aruntii family tomb, and that Varro’s description of the tomb of Porsena inspired them to ennoble their family by making them spring from the mythical Arunte; or that both Varro and the Aruntii may have been drawing on a legendary description of an Etruscan funerary monument; or that Varro saw or had a description of the monument at Albano, exaggerated its size, and misattributed it to Chiusi. The legendary connection with a labyrinth is thought to derive from the presence of a complex at Chiusi of underground passages, or close by at Albano of subterranean galleries, later used as catacombs.

Meanwhile, a different legend had developed in republican Rome. Livy tells the tale of how, during the time of the kings, the Romans and the inhabitants of Alba Longa agreed to settle their differences by armed combat between two sets of triplets, the Horatii brothers from Rome and their counterparts from Alba, the Curiatii. Rome rapidly went two-nil down, but the surviving Horatius killed first one Curiatius, then the second, then the third. ‘Their graves,’ concludes Livy, ‘yet remain in the place where each one fell, the two Roman graves in one place near Alba, and the three Alban tombs towards Rome’.15 The legend may have been aetiological, to explain how Alba Longa came to be under Roman control without mass bloodshed, but Livy evidently saw the story as explaining the existence along the Appian Way of a number of large tombs, possibly of Etruscan origin. By late republican times the legend was taught as an example of bravery, of heroic self-sacrifice in the interests of the state, and of the ultimate victory of Roman bravery, whatever the odds.16

In 1595 the architect Leone Battista Alberti attributed to the structure at Albano, with its five truncated cones, a link with the legend of the Horatii and Curiatii: one broken cone for each dead body.17 Milordi on the grand tour, reading their Livy and modestly identifying themselves with the heroes of Roman myth, will have lapped it up. If Norborne Berkeley saw the structure on his

10. P. Chiarucci, ‘Il sepolcro detto degli Orazi e Curiazi in Albano’, Documenta Albana, 2(8) (1986), 7–12, refining the dating in F. Coarelli, Dintorni di Roma (Laterza, Rome and Bari, 1981), 43.

11. For an example, see C. Ghini, Il sepolcro detto degli Orazi e Curiazi ad Albano (Quaser di Severino Tognon, Rome, 1994), 3, reproducing G. Körte, I rilieve delle urne etrusche, II, tav. XCV (Berlin, 1896).

12. Pliny, Natural History 36.91–3.13. Chiarucci, ‘Il sepolcro’, 10, citing A. Nibby, Del monumento sepolcrale volgarmente detto degli Orazi e

Curiazi (Rome, 1834).14. Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum XIV 2260.15. Livy, History of Rome 1.24–6.16. A. Boëthius and J.B. Ward-Perkins, Etruscan and Early Roman Architecture (1970; rev. T. Rasmussen and

R. Ling, New Haven/London, 1978), 178.17. Chiarucci, ‘Il sepolcro’, n. 4, 10; Ghini, Il sepolcro, n. 4, 1.

221-228_BGAS131_Evans.indd 224 22/01/2014 15:28

-

MONuMENT TO THE HORATII AND CuRIATII 225

grand tour, its singularity is bound to have made an impression on him, and George Barclay his tutor and guide will have made sure that Berkeley was aware of the imputed connection with the heroic story in Livy.18

That is the most likely explanation for Berkeley commissioning a similar structure at Stoke Park, but other explanations are possible. Drawings by Thomas Wright show one looking something like the original structure and one with the base formed of arches.19 They might have been a response to Berkeley’s description of what he wanted. But if it was Wright who introduced the idea to Berkeley, that prompts the question what source Wright may have had. One candidate might be David Humphreys’ translation, published in London in 1722, of Bernard de Montfauçon’s Antiquité expliquée.20 Humphreys’ translation, punctuation and all, runs:

The following Sepulchre or Mausoleum crown’d with five Pyramids of a Conick Figure, but all moulder’d and defac’d by Time, is to be. seen at Albano, and is reputed the Sepulchre of the Curiatii., as it has been call’d for along time: But this is only popular report. There being no Inscription to give Testimony to it. We ought therefore to enquire into the Time when it was first called so, because if that has been the Tradition for a great many Ages, it will carry some face of Probability. The five Pyramids signify probably that it was made for five Persons; but forasmuch as there is no Inscription, we cannot tell who they were.21

De Montfauçon illustrated his text with an engraving of a structure consisting of a concave ogee plinth, above which was a convex frieze, both with dentilles, supporting seven courses of squarish stone blocks, topped by a projecting course of slabs. Above rise five topless cones, with vegetation growing among them, to indicate that it is a ruin, and a man clambering about, presumably to give scale.

Another possibility, less likely, is that Berkeley had in mind not the Alban monument to the Horatii, but Pliny’s account of Varro’s description of the tomb of Porsena. What the latter may have looked like has puzzled architects ever since. Christopher Wren speculated about it and discussed it with Robert Hooke.22 Wren actually attempted a hypothetical reconstruction of the monument, a fact published in 1750,23 which Berkeley or Wright or both might have read or heard about.

Berkeley had his version of the tomb of the Horatii and Curiatii built in 1761–2. In November 1761 his accounts include an entry for ‘Helping the carpenters to raise the broken temple in the Park’24 – broken, not to represent death as in the vocabulary of the English neoclassical funereal monument, but because Berkeley was replicating a ruin. That was the state the structure at Albano was in when Berkeley must have seen it, as shown by Wilson’s and Busiri’s paintings, Adam’s drawing (which is dated to c.1755) and de Montfauçon’s engraving, and also by the painting in 1792 by the Bath artist Thomas Barker.25 ‘Stone for the new temple in the Park’ was being paid

18. For Barclay and Norborne Berkeley’s grand tour, see W. Evans, ‘I begin to look about me: a Gloucestershire gentleman’s education’, The Regional Historian 17 (2007), 28–31, drawing largely on Badminton Muniments (Bad. Mun.), Fm S/G 5/1. I am grateful to the duke of Beaufort for permission to inspect Berkeley’s personal papers at Badminton.

19. Avery Archit. and Fine Arts Libr., New York, Thomas Wright’s sketchbook, 66, 67.20. J. Tonson and J. Watts, Antiquity Explained as Represented in Sculpture (London ,1722; facs. repr. Garland,

New York, 1976).21. Ibid. book 3, pt 1, 87.22. R. Hooke, Diary, 4, 17 18 and 20 Oct. 1677.23. C. Wren, Parentalia, Tract V.24. GA, D 2700/QP 3/6/6, b.7, Stoke accounts.25. Nat. Mus. and Gallery, Cardiff, NMW A 454.

221-228_BGAS131_Evans.indd 225 22/01/2014 15:28

-

226 WILLIAM EVANS

for in January and June 1762, and in August 1762 Berkeley’s accounts record payment to ‘Husey 6 days sawing and rubbing of Stones for the monument in the Park’. James Russell has reconstructed what the monument looked like.26

The monument had been erected by 1764, when bishop Pococke visited:

We came to a brow on which is built a Model of the Monument of the Horatii at Albano with four round Obelisks on an arch’d building, adorn’d with a pediment every way. In the Freize round the four sides is this inscription

Memoria Virtutis Heroicae SPQR27

So whilst Wright’s first drawing of the structure follows the original (or Humphreys/de Montfauçon or both), his design for Berkeley, his second drawing, introduced the pediments and arches and so departed somewhat from the original.

Three other structures may possibly have influenced what Wright designed, or may have some other connection with the Stoke Park monument. When Wright and Berkeley visited Castle Howard on their tour in August 1750,28 they may have seen Nicholas Hawksmoor’s Carrmire Gate, a heavily rusticated stone structure with the arch surmounted by four stumpy obelisks and a pediment atop the lot. A second possibility is that Wright, who came from County Durham, may have recalled the churchyard of St Mary’s, Gateshead, where a Victorian neo-gothic structure of similar appearance, named in a print as The Anchorage (presumably a hermitage, unless that refers to the stretch of river in the background), and now known as the Green mausoleum, is said to have replaced an earlier structure of similar, but not gothick, design.29 Thirdly, between 1730 and 1750 the Jacobite William Morice erected in his park at Werrington on the Devon-Cornwall border a similar structure (later called The Sugar Loaves). Pococke had noted it on his visit in 1750, but there is no evidence to suggest that the version at Stoke Park is modelled on that one, or vice versa.30 The so-called Devil’s Chimney at Studley Royal in North Yorkshire, dated c.1735, is said to have been modelled on the Albano tomb, and it is to be inferred that Berkeley and Thomas Wright visited Studley Royal on their 1750 tour; but as that structure has a flat roof and no obelisks or pylons, a derivation seems unlikely.

Pococke’s description of Berkeley’s version concludes: ‘On the side on wch the Epitaph is inscrib’d, it is almost inaccessible, which may have some meaning.’ If there was a meaning, it is difficult to guess what it might have been. Pococke may have read into the inaccessibility an intention that Berkeley did not have. But if he was right, perhaps Berkeley had had second thoughts about the propriety of the inscription, and did not want people to read it, but that prompts the question why. Polite visitors of sensibility were just as keen to uphold perceived Roman virtues in 1764 as they had been in 1761. There is no reason why Berkeley should have repented of his inscription. The only change in circumstances by the time Pococke viewed the inscription was that Berkeley had obtained his peerage, and that would not have made any difference. Could Pococke, remembering that the Jacobite William Morice had built a similar structure at Werrington,

26. J. Russell, Three Garden Buildings by Thomas Wright at Stoke Park, Bristol (1988), 5–6 and figs. 10–11; Russell, ‘Archaeol. of Stoke Park’. More recent excavations are described in Hunt and Russell, ‘Tomb of the Horatii’.

27. Brit. Libr. Add. MS 14260, f. 138.28. Berkeley to Elizabeth, 28 Jul. and 1 Aug. 1750: Bad. Mun., Fm K 1/2/14; T. Wright, ‘Tour through parts

of England in the year 1750 with Narbon Berkeley, esq, Prince, and late Lord Botetourt’, The Reliquary 15 (1874–5), 216.

29. Print, ‘St Mary’s Gateshead and the anchorage’, reproduced in F.W.D. Manders, History of Gateshead (1973).

30. G. Daw, ‘Werrington Park’, in Follies 14(4:55) (2003), 8. I am grateful to James Russell for the reference.

221-228_BGAS131_Evans.indd 226 22/01/2014 15:28

-

MONuMENT TO THE HORATII AND CuRIATII 227

have wrongly assumed that the Stoke structure was a crypto-Jacobite gesture of support for the Pretender, whose cause by 1764 was irretrievably lost? Given that Werrington has sham gothick castles, and at Wentworth in West Yorkshire Thomas Strafford had used that icon as a gesture of Jacobite sympathy, Pococke might have drawn a similar conclusion but decided to record his thoughts obliquely. If so, his surmise was groundless, because Berkeley was loyally Hanoverian and had publicly disassociated himself from the Jacobites many years before by signing, late in 1745, the ‘Association’. This was a public document expressing the signatories’ sensibility of, and a promise to pay towards, ‘the raising of able-bodied men to recruit H.M.’s land-forces.’ Berkeley’s co-signatories to the document for the parish of St George, Hanover Square, included Grafton, Horace Walpole, Pelham and Conway.31

Another possibility, assuming that Pococke was right to attribute some significance into the inaccessibility of the inscription, is that Berkeley had become aware of an interpretation of the inscription that he had not realized was possible when he commissioned the wording. In Livy’s version of the story the victorious Horatius returned to Rome, acclaimed by all except his sister, who turned out to have been betrothed to one of the Alban Curiatii. Angered by her lamentations, the Horatius killed her too, on the spot. Convicted of her homicide, and with the noose around his neck, he adopted the novel ploy of an appeal to the people, who reprieved him. Later generations are thought to have made up the story, or to have embellished it, to explain the origin of a right of appeal against the death penalty. So in commemorating the bravery of the Horatii (and Berkeley’s inscription shows it was their bravery he commemorated, not their deaths), Berkeley might also be taken to have endorsed the action of a man who killed his sister. At one time Berkeley and his sister Elizabeth were not on good terms. An anonymous letter, undated, but thought to have been written in 1763, a year before Pococke’s visit, refers to Berkeley’s differences with his sister: ‘two of the most amiable people … but who have both unfortunately too great a spirit to avow how much the unhappy difference that subsists between them be to each’, and urges him to effect a reconciliation.32 If Pococke was aware of the estrangement, he may just possibly have had such a consideration in mind.

After Berkeley’s death the monumental ruin itself became ruinous. It was undermined by quarrying, and by the time the Bristol artist Samuel Loxton sketched it in the 1920s what remained of it listed badly.33 Its origin and significance became forgotten, and it was known locally as The Old Owl House. Only a few pieces of masonry now remain, overgrown and hardly visible.

In the meantime the icon acquired new life in the repertoire of garden features offered by designers to their patrons. From 1757 to 1768 Jean François de Neufforge published drawings for a water feature based on the Horatii and Curiatii monument theme, but with water spouting from orifices at every level and elevation of the structure.34 Great fun, but not quite conveying the heroism that Norborne Berkeley wished to commemorate, or that he wished polite visitors to his symbol-laden landscaped acres to associate with their smooth and ambitious owner.

31. ‘Association against the Rebellion’, 13 Nov. 1745: Westminster City Archives, C 765a.32. M. Richards, Introduction to Bad. Mun. catalogue; Bad. Mun. Fm S/G4/6.33. Loxton prints, City of Bristol Ref. Libr.34. J.F. de Neufforge, Receuil elémentaire d’architecture (Paris, 1757–80: repr. Gregg, Farnborough, 1967).

221-228_BGAS131_Evans.indd 227 22/01/2014 15:28

-

221-228_BGAS131_Evans.indd 228 22/01/2014 15:28