BF L5 1992

-

Upload

nabiellaarifin -

Category

Documents

-

view

217 -

download

0

description

Transcript of BF L5 1992

Copyright 1992 h� i!i� J(ursulI vi Hone alit! Joini .ci�rgert. Iii (4)P poraie�I

398 TI-IE JOURNAL ()F BONE ANt) JOINT SURGERY

Burst Fracture of the Fifth Lumbar Vertebra3

BY CHARLES A. FINN. M.D.t. AND F. S. STAUFFER. M.D4. SPRINGFIELD. IL[.INOIS

IilteSti#{231}(ltiO?l performiteil at the Division ofOrthopaedics amid Rehabilitation, Departiiteitt ()f�Slii�gerv.

.S’outhern Illinois University Sc/tool at Medicine, Spriitgfield

ABSTRACT: Burst fracture of the fifth lumbar verte-

bra is a rare injury. We report the cases ofseven patients

who were treated conservatively by immobilization for

six to eight weeks in a body-jacket cast that included one

lower extremity to the knee. The patients were allowed

to walk ten to fourteen days after the injury. A thoraco-

lumbosacral orthosis was worn for an additional three

months. No patient had an injury to the sacral root. Two

patients had mild lower lumbar motor-root deficits that

resolved within one year. All patients had an occasional

backache, and two had intermittent radicular-type pain

in the distribution of the fifth lumbar or first sacral-

nerve root. The degree of compromise of the spinal

canal could not be directly related to the degree of

neurological deficit; that is, a large compromise of the

spinal canal did not necessarily result in a major loss of

neurological function. There was no early or late loss of

lordosis between the cephalad end-plate of the fourth

lumbar vertebra and the cephalad aspect of the sacrum,

and there were no signs of progressive collapse of the

vertebral body in any patient. In our series, the burst

fractures of the fifth lumbar vertebra were stable in-

juries that caused minimum neurological deficits, and

treatment by immobilization in a body-jacket cast was

effective.

In 1953, Holdswonth and Hardy� distinguished burst

fractures from fracture-dislocations in their two-column

(anterior and posterior) classification system. Denis

modified this classification to include a third (middle)

column. He emphasized that if two of the three columns

were disrupted. the fracture was inherently unstable.

However, he reported the case of only one patient who

had a burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra, and he

did not give recommendations for treatment. We are

aware of only two previously published reports dealing

specifically with burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vente-

bra: one report included three patients, and the other

included four’3. Seven patients who had sustained a burst

fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra and were treated by

:3N() benefits in dily form have been received or will he received

from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of

this article. No funds were received in support of this study.tSuite C’. 1(5)1 37th Street North. St. Petersburg. Florida 33713.

�Department of Surgery. Southern Illinois University School ofMedicine. P.O. Box 19230. Springfield. Illinois 62794.

immobilization in a body-jacket cast were followed to

determine the effectiveness of this management.

Materials and Methods

Between January 1984 and December l99(), 587 frac-

tunes of the spine were treated at the Division of Ortho-

paedic Surgery at the Southern Illinois University School

of Medicine. Two hundred and seventy-three fractures

involved the cervical spine. and 314 involved the thora-

columbar spine. There were seven burst fractures of the

fifth lumbar vertebra ( 1 .2 per cent of all fractures of the

spine and 2.2 per cent of fractures of the thoracolumbar

spine). All were true burst fractures that met the criteria

of involvement of two of the three columns, as described

by Denis (Figs. 1-A and 1 -B). Compression fractures and

fractures that were due to osteoporosis. with involve-

ment of one column, were excluded from the study4”.

There were five men and two women: the ages ranged

from twenty-two to forty-nine years (average, thirty-five

years). The duration of follow-up ranged from twelve to

seventy-two months (average, thirty-six months). The

injury had been caused by a fall in three patients and by a

motor-vehicle accident, weight-lifting, water-skiing, and

an airplane crash in one each. Five of the patients had

associated injuries: three had another fracture of the

spine (one, of the eighth thoracic vertebra and two, of the

second lumbar vertebra): one. bilateral fracture of the

calcaneus: and one, bilateral fracture of the ankle.

The neurological status of each patient was docu-

mented. The development of neurological deficits. radic-

ular pain, and back pain was assessed at regular intervals.

Plain radiographs and computed tomography scans

were made initially, in order to determine the degree of

spinal or foraminal compromise by osseous fragments or

disc material. The wedge index and the degree of lordosis

were determined at the time of injury and at follow-up

intervals. The wedge index was calculated in the standard

fashion, by measurement of the height of both the ante-

nor and posterior bodies of the fractured vertebra and

calculation of the ratio. The lower the ratio, the greater

the amount of anterior compression. The lordotic angle

was calculated from the cephalad end-plate of the fourth

lumbar vertebra and the cephalad aspect of the sacrum.

The development of late degeneration of the disc space

and arthrosis of the facet (zygapophyseal joints) was

assessed by lateral and oblique radiognaphs of the lum-

FI,. 2-A Fi;. 2-B

BURST FRACTURE OF THE FIFTH LUMBAR VERTEBRA 399

V(i)I.. 74-A, NO. 3. MAR(’II 1992

Fi;. 1-A Fi;. I-B

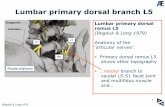

Figs. I-A and 1-B: Case 6. Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs ofthe caudad portion ofthe lumbar spine and the sacrum. demonstrating

a typical burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra.

Fig. I-A: Anteroposterior radiograph showing normal sagittal alignment.

Fig. I -B: Lateral radiograph demonstrating involvement of the anterior and middle columns. with 3() degrees of lordosis and a wedge index

of 24/30 (0.8). The posterior column is intact.

ban spine that were made during follow-up.

All seven patients were treated by immobilization

for six to eight weeks in a body-jacket cast that included

one lowenextremity to the knee.They then wore a thona-

columbosacral onthosis for an additional three months.

The patients were allowed to walk ten to fourteen days

Figs. 2-A and 2-B: Case 2. Lateral radiographs demonstrating no loss of lordosis or change in the wedge index from the time of injury tofollow-up at thirty-six months.

Fig. 2-A: Initial radiograph. There is 28 degrees of lordosis and a wedge index of 25/32 (0.78).

Fig. 2-B: At the thirty-six-month follow-up, there is 28 degrees oflordosis and a wedge index of 27/34 (0.79). The difference in the measured

height of the anterior and posterior columns is most likely secondary to a magnification error.

Figs. 3-A. 3-B. and 3-C: Case 2. Computed tomography scan dem-onstrating more than 90 per cent compromise of the spinal column:

the only neurological deficit was weakness (4 of 5) of the extensor

hallucis longus that subsequently had resolved at the one-year follow-

up.

Fig. 3-A: Transverse cut showing more than 90 per cent compromiseof the canal and foraminal encroachment.

after the injury unless this was contnaindicated because

of injuries of the lower extremity.

FIC. 3-B

Sagittal reconstruction demonstrating involvement of the anterior

and middle columns, with retropulsion of hone.

FtC;. 3-C

Transverse scan made one year after the injury. There is consider-

able compromise of the canal but the patient had no neurological

deficit at this time.

400 C. A. FINN AND E. 5. STAUFFER

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

Two of the seven patients had lumbar motor-root

deficits. One (Case 4) had weakness (3+ of 5) of the

extensor hallucis longus and plantan flexors bilaterally.

At OflC year, the patient had completely recovered cx-

cept for weakness (4 of 5) of the extensor hallucis longus

on one side. Another patient (Case 2) had weakness (4

of 5) of the extensor hallucis longus that subsequently

resolved by the one-year follow-up. Both patients had

compromise of the spinal canal of more than 90 per cent,

as shown on computed tomographic scans. Of the five

remaining patients who had no lumbar motor-root def-

icits. three (Cases 3, 6, and 7) had compromise of the

spinal canal of 50 per cent or more, as shown on com-

puted tomography scans. and two (Cases I and 5) had no

occlusion of the spinal canal (Table I).

Sacnal root deficits were not present and did not

develop in any patient. All patients maintained control

of function of the bowel and bladder. and all had normal

penineal sensation.

Initial radiographic evaluation revealed wedge mdi-

ces ranging from 0.75 to 0.97 (average, 0.85). At the most

recent follow-up. the indices had changed little: the range

was 0.66 to 0.97 (average, 0.82). On the basis of these

indices. signs of progressive anterior collapse of the yen-

tebral body were not demonstrated in any patient. Also.

substantial loss oflordosis did not occur during follow-up five of the seven patients had occlusion of the spinal

(Figs. 2-A and 2-B). The angle between the cephalad

end-plate of the fourth lumban vertebra and the cephalad

aspect of the sacrum ranged from 18 to 35 degrees (av-

enage, 29 degrees). At the latest follow-up, the range was

15 to 35 degrees of londosis (average, 27 degrees) (Table I).

Evaluation by computed tomography revealed that

canal and encroachment of the fonamen of at least 50 pen

cent; three of the five (Cases 2, 4, and 7) had compromise

of more than 90 per cent (Figs. 3-A , 3-B, and 3-C). The

remaining two patients (Cases 1 and 5) had no evidence

of occlusion of the spinal canal on of fonaminal encroach-

ment on computed tomography.

BURST FRACTURE OF THE FIFTH LUMBAR VERTEBRA 401

VOL. 74-A, NO. 3. MARCH 1992

TABLE I

DATA ON THE PATIENTS

Estimated

Compromise

Case

Sex,

Age

Duration of

Follow-up

Neurological

Status

Wedg e Index Lordosis (Degrees) on Computed

Initial Follow-up Initial Follow-up Tomog. Scans

(Yrs.) (Mos.)

1 M. 49 33 Intact 0.94 0.94 29 25 None

2 M. 23 47 Weakness (4/5) of

extensor hallucis longus:

resolved

0.78 0.79 28 28 >90%

3 F.49 12 Intact 0.96 0.95 18 15 60%

4 M. 43 16 Bilat. weakness (3#{247}15)of

extensor hallucis longus

and plantar flexors;

resolved, except weak

(4/5) extensor hallucis

longus on one side

0.77 0.66 34 30 >90%

5 M, 25 72 Intact 0.97 0.97 35 35 None

6 F, 35 36 Intact 0.8 0.74 30 28 50%

7 M. 22 36 Intact 0.75 0.72 28 26 >90%

*Lordotic angle between the fourth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum.

FIG. 4-A FIG. 4-B FIG. 4-C

Figs. 4-A, 4-B. and 4-C: Case 7. Lateral and oblique radiographs showing a burst fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra with degenerative

changes of the facets and disc space. The radiographs were made thirty-six months after the injury.

Fig. 4-A: Lateral radiograph demonstrating degeneration of the disc space, with narrowing between the fourth and fifth vertebrae and the

fifth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum.

Fig. 4-B: Left oblique radiograph demonstrating degenerated facetjoints at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum.

Fig. 4-C: Right oblique radiograph demonstrating degenerated facet joints at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum.

402 C. A. FINN AND E. S. STAUFFER

THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY

At the most recent follow-up, two of the seven pa-

tients had some degree of radiculan pain in the distnibu-

tion of the fifth lumbar on the first sacnal nerve. These

were the same two patients who had lumbar motor-root

deficits. Neither patient thought that the pain was suffi-

cient to warrant an operative decompression.

All seven patients reported occasional backache dun-

ing the period of follow-up. In two patients (Cases 4 and

7). hypentrophic facet joints and a degenerated disc de-

veloped at later follow-up intervals (Figs. 4-A, 4-B, and

4-C). The remaining five patients had no identifiable

radiographic evidence of degeneration of the lumbar

spine at subsequent follow-up visits. None of the patients

thought that the pain was sufficient to warrant an open-

ative arthrodesis.

Discussion

There have been very few reports in the literature

regarding burst fractures of the fifth lumbar vertebra.

Even in the many reports of fractures of the thonacolum-

ban spine, little has been mentioned about burst fractures

involving the fifth lumbar vertebra24”’2’4. Osebold et a!.

reported on one patient who had a burst fracture of the

fifth lumbar vertebra. as did Denis, but neither author

discussed the treatment. To our knowledge, two previous

reports have specifically addressed burst fractures of the

fifth lumbar vertebra’3.

Fredrickson et a!., in 1982,neported the results in four

patients who had a fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra.

The treatment was individualized and was based on the

neurological status of the patient. the stability of the

fracture, and any associated injuries. An operation was

performed because of progressive or substantial neuro-

logical loss. The authors stated that the degree of neuno-

logical loss corresponded to the amount of compromise

of the fonamen or spinal canal that was seen on computed

tomography scans. Three of the four patients had had

laminectomy. decompression, and postenolatena! arthro-

desis from the fourth lumbar vertebra to the sacrum.

Little improvement in the neurological status of the

patients was found after the decompression. The authors

also reported that internal fixation added no benefit.

Court-Brown and Gentzbein, in 1987, reported on

their experience with three patients who had a burst

fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra. They treated two

patients conservative!y,with no major complications. The

other patient, who had had posterior decompression,

internal fixation, and anthrodesis, had persistent pain in

the back. There was a loss of londosis between the fourth

lumbar vertebra and the sacrum in all three patients.

despite the use of instrumentation in one of them. The

authors concluded that a conservative regimen seemed

appropriate for fractures at the lumbosacra! junction.

In our series, since the burst fractures were in the

lordotic area of the spine and the patients were neuno-

logically stable, with only minor root injuries, non-open-

ative treatment was chosen. The indication for early

operation would have been progressive neurological loss.

Late decompression and anthrodesis was reserved for

patients who had substantial compression of the lumbar

root, causing considerable pain. No patient met any of

these criteria for operation.

There was no relationship between the amount of

compromise of the spinal canal and the severity of the

neurological deficit. Three patients had more than 90 pen

cent occlusion of the spinal canal, and for another two

patients, at least 50 per cent compromise of the canal was

seen on computed tomographic scans. Despite this, no

patient had a sacral root deficit, and only two patients

had minor lumbar motor-root deficits that, for the most

pant, had resolved at the one-year follow-up. All patients

had an occasional backache, and two patients had mild

radicular-type pain. These complaints seem minor when

the potential for severe damage to the cauda equina from

the fragments of bone in the spinal canal are considered.

Furthermore. we have no indication that an operative

procedure would have lessened the prevalence of the

persistence of pain in the back or radicular pain.

There was no progressive loss of lordosis between the

fourth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum. This connespon-

ded to the fact that no appreciable progression of col-

lapse of the anterior vertebral body occurred. The angles

of lumbar londosis and the wedge index changed little

between the initial evaluation and the time of follow-up.

Given these results. we believe that anthnodesis of the

spine is not necessary to prevent the loss of lumbar

lordosis.

In patients who have a burst fracture of the fifth hum-

bar vertebra, the presence of another fracture of the

spine should always be considered. Three of our seven

patients had a fracture at another level of the spine; none

had an associated neurological injury or any neurological

loss at the other level. There was one compression frac-

tune of the eighth thonacic vertebra and two burst-type

fractures of the second lumbar vertebra. Because of the

slight neurological injuries, with only lower root deficits,

these concurrent fractures did not contribute substan-

tially to the ultimate clinical outcome. Therefore, in the

interpretation of the results. these concomitant fractures

were ignored.

In conclusion, in our patients who had a burst frac-

tune of the fifth lumbar vertebra, immobilization in a cast

stabilized the fracture and provided a good clinical result.

Our patients did not deteriorate neurologically, and the

amount of londosis on collapse of the vertebral body did

not progress during follow-up.

References

1. Court-Brown, C. M., and Gertzbein, S. D.: The management ofburst fractures of the fifth lumbar vertebra. Spine. 12: 308-312, 1987.

2. Denis, Francis: The three column spine and its significance in the classification of acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries. Spine. 8:

817-831, 1983.

BURST FRA(1URE OF THE FIFTH LUMBAR VERTEBRA 403

3. Fredrickson, B. E.; Yuan, H. A.; and Miller, Howard: Burst fractures of the fifth lumbar vertebra. A report of four cases. .1. Bone and Joint

Si�r�g., 64-A: 1088-1094. Sept. 1982.

4. Holdsworth, F. W.: Fractures, dislocations. and fracture-dislocations of the spine. .1. Bone and Joint Surg., 45-B(1): 6-20. 1963.

5. Holdsworth, F. W., and Hardy, Alan: Early treatment of paraplegia from fractures of the thoraco-lumbar spine. J. Bone and Joint Siirg.,

35-B(4): 540-550. 1953.

6. Jacobs, R. R.; Asher, M. A.; and Snider, R. K.: Thoracolumbar spinal injuries. A comparative study of recumbent and operative treatment

in 100 patients. Spine, 5: 463-477. 1980.

7. Kaufer, Herbert, and Hayes, J. T.: Lumbar fracture-dislocation. A study of twenty-one cases. J. Bone and Joint Surg., 48-A: 7 12-730,

June 1966.

8. McAfee, P. C.; Yuan, H. A.; and Lasda, N. A.: The unstable burst fracture. Spine. 7: 365-373, 1982.

9. Nykamp, P. W.; Levy, J. M.; Christensen, F.; Dunn, R.; and Hubbard, J.: Computed tomography for a bursting fracture of the lumbar spine.

Report of a case. J. Bone amid Joint Surg., 60-A: I 108-I 109, Dec. 1978.

10. Osebold, W. R.; Weinstein, S. L.; and Sprague, B. L.: Thoracolumbar spine fractures. Results of treatment. Spine. 6: 13-34, 1981.

I I . Stauffer, E. S.: Treatment of fractures of the thoracolumbar spine. In Spina/ Disorders. Diagnosis amid Treatment, pp. 380-390. Edited by

Daniel Ruge and L. L. Wiltse. Philadelphia. Lea and Febiger. 1977.

I 2. Stauffer, E. S.: Mechanism of injuries to the spine. In Spina/ Deformities and Neuro/ogica/ Dysfunction, pp. 65-73. Edited by S. N. Chou

and E. L. Seljeskog. New York. Raven Press. 1978.

13. Stauffer, E. S.: Fractures of the lumbar spine. In Surgery ofthe Muscu/oske/eta/System, edited by C. McC. Evarts. Vol. 2. pp. 4:297-4:309.

New York,Churchill Livingstone, 1983.

14. StaufTer, E. S.: Fracture-dislocations of the lumbar spine. In The Mu/tip/v Injured Patient wit/i Comp/ex Fractures, pp. 162-178. Edited by

M. H. Meyers. Philadelphia. Lea and Febiger. 1984.

VOL. 74.A, NO. 3. MARCH 1992