Best Practice in Large Scale Assessment

-

Upload

corina-ica -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of Best Practice in Large Scale Assessment

Best Practice Series

Guidelines for Best Practicein Large Scale Assessment

Contents Page No

Foreword 2

1. Introduction 3

2. Context of assessment 4

3. Good job description 5

4. Design of the assessment process 6

5. Use of technology 8

5.1 Internet-based assessment 9

6. Recruitment 10

7. Assessment procedures 12

7.1 Initial sifting 12

8. Balancing individual candidate needs and organisational costs 14

8.1 Communication 14

8.2 Feedback 15

9. Need for organisational policy 16

10. Maintaining standards 17

11. Monitor fairness and effectiveness 18

12. Data protection act 19

13. Further information 20

Best Practice Series > 1

This Best Practice Guide has been written to

address the needs of organisations that are using

standardised assessment processes with large

numbers of candidates. The size of these projects

highlights some distinctive issues that are not

generally concerns in smaller scale assessments.

They include careful planning of resources, the

effective use of IT and formulating an

organisation wide policy.

This guide has been written to complement rather

than duplicate the rest of the SHL Best Practice

Guidelines. These can be accessed from the SHL

Website at www.shl.com or from our Client

Support Centre on 0870 070 8000.

Foreword

2 > Best Practice Series

Large scale assessment is no different from the

smallest selection procedure in aiming to provide

the best information possible on each individual

to allow effective decisions to be made. Both

should start from a clear understanding of the job

requirements, move on through the use of

appropriate tools to generate clear indications of

suitability for each individual, which can form the

basis for objective decision making. However,

where large numbers are involved the impact of

less than optimal practice can be far greater.

Large scale assessments tend to occur in three

main situations:

• Where organisations are recruiting significant

numbers of applicants in one campaign

• Where there are a large number of roles

needing to be filled on an ongoing basis

• Where there are simply a very large number of

applicants who are able and willing to perform

the role.

Examples of such projects include:

• Business start ups

• Graduate milkrounds

• Recruitment in economically

disadvantaged regions

• Recruitment by famous

organisational “names”.

They differ from more conventional and

modest recruitment processes in a number of

significant ways:

• The large numbers of applicants tends to

create a “multiplying” effect - if the process is

flawed in any way, even a minor error will get

compounded into a more serious problem

because of the sheer weight of numbers

• The logistics of processing large numbers of

applicants requires significant investment of

resources and management

• Large numbers of applicants can mean that

small changes in the efficiency of the process

can have a significant impact on the quality of

the assessment process (“validity”)

• The large number of people being processed

allows more detailed statistical monitoring and

evaluation of the process to be undertaken,

which can clearly show whether the process is

fair and valid

• The significant, high profile nature of the

process may make it more controversial and

thus likely to be challenged by candidates or

investigated by external agencies, e.g. Press,

Commission for Racial Equality (CRE), Equal

Opportunities Commission (EOC)

• The large number of assessors required to

process all the applicants means that formal

procedures must be instituted to prevent

inconsistencies in decision making.

This guide therefore has been designed to cover

some of the major issues in the design of a large

scale selection process. Much of the content will

be relevant when large numbers of people are

being assessed for other reasons, e.g. in a

development programme.

1. Introduction

Best Practice Series > 3

It is important to consider the aims of the

assessment. While there may be a straightforward

answer to this question in terms of number of

hires or identifying development needs, there are

often other, sometimes conflicting, requirements

of an assessment process. It is important to be

aware of these requirements.

In selection, all organisations want to fill posts

with the best available candidates, but practical

business constraints may limit what can be done.

There may be disagreement about who is a

desirable candidate: head office might want a

customer service ethic but local managers might

be more interested in getting the goods on the

shelves.

In addition to the straightforward constraints on

the system, there may be a number of secondary

aims, e.g.

• To leave a positive impression of the

organisation among candidates who will also

be clients

• To bolster the image of the organisation as

thorough, leading edge, informal

• To improve managers’ understanding of the

assessment process

• To highlight the capability of the HR

department.

As with any large project, it is important that all

these different agendas are understood and the

project specification is clear about what can be

realistically achieved within the constraints.

Otherwise there is a danger that even a well

delivered project will lead to dissatisfaction

among some of the stakeholders.

On a more practical note, if the posts must be

filled by a certain date, then the selection system

needs to be tailored to this timetable. Assessment

can use large amounts of managerial time, which

the organisation might prefer to invest in other

ways. Involving line managers in interviews and

assessments can have positive benefits in terms

of buy-in to the procedure, hands on knowledge

of requirements and realistic understanding of the

job for candidates, but the opportunity costs of

taking managers away from their day to day

concerns may not be acceptable to the

organisation. There are also opportunity costs

for human resource departments in running

large-scale assessments. It can drain resources

from other responsibilities and leave other

tasks undone.

Many organisations are using technology to

automate their processes. This can range from

using Internet sites for recruitment, allowing

people to apply via e-mail, to sophisticated

systems that can shortlist candidates automatically

or schedule their interviews. This use of IT carries

with it many advantages, such as efficiency and

consistency, as well as some potential hazards.

Systems need to be well designed and managed

to deliver the benefits they promise. We have

devoted a whole section of this guide to issues

in using technology effectively (see section 5,

page 8).

As well as time and resource constraints, there

will be limits to financial resources available. Costs

of recruitment may be high and where multiplied

by large numbers of candidates, it is important to

ensure that budgets are sufficient to cover

requirements.

2. Context of assessment

4 > Best Practice Series

• Identify the major stakeholders in the

assessment process

• Clarify the needs of each stakeholder and

consider how realistic these are

• Assess the likely attractiveness of the job

taking into account:

• the role itself

• the benefits package

• the attractiveness of the organisation

• local economic conditions.

• Consider alternatives to large scale

assessment process, such as temporary

or contract workers, outsourcing

and subcontracting

• Check the available resources in terms of

time, money and people against the likely

needs of the selection process

• Evaluate the costs and benefits of using

technology in the process.

Context of Assessment Checklist

Before embarking on the design of the process, it

is important to focus on the job that is being

performed. This preliminary ground work or “job

analysis” is a significant first stage in the process

because it:

• Encourages the designer to focus on the role

being targeted and identify clearly the

essential and desirable skills that are

necessary for its successful performance.

There may be a large number of people

performing the role once the assessment has

taken place, so it is worthwhile being as

accurate as possible

• Makes the role requirements explicit to all

parties in the selection process, and provides

an opportunity to check consensus about the

role among hiring managers, senior managers

and HR personnel

• Ensures that candidates can be given a

realistic picture of the job. This is helpful in

encouraging self-selection among candidates.

It can encourage good candidates who have

skills which match the challenges of the role.

Equally it can discourage those who are

under-qualified. Communicating the negative

parts of the role can help in dispelling over-

romanticised visions of the role

• The data can be used in defending against

legal challenges to explain and justify the

relevance of the selection process, should this

be necessary.

More information on job analysis techniques and

issues can be found in the SHL Guidelines for Best

Practice in the use of Job Analysis techniques.

Available from the SHL website, www.shl.com

or by contacting our Client Support Team

on 0870 070 8000.

3. Good job description

Best Practice Series > 5

• Identify the main subject matter experts for

the role: both job incumbents who

understand how it is now and managers

who understand how it may change in

the future

• Use appropriate techniques to generate a

clear description of the job including:

• The main tasks and key objectives

• The skills that are needed to allow job

incumbents to do it well

• The context in which the job is performed.

• Differentiate between what is essential for

the role, and desirable qualities

• Consider people with special needs, who

may need the job adapted in some way

• Document the findings clearly, and store

them where they can be accessed easily.

Job Analysis Checklist

The design of the selection process should flow

from the job analysis results. This is good practice

for any assessment scenario but it is especially

important for large scale processes. Relatively

small increases in the validity of the tools chosen

will have a surprisingly large impact in

organisational terms when many posts are to be

filled. If one call centre operator is responsible for

£50,000 of sales to an organisation, then one

hundred will be worth £5 million. A 5%

improvement in average performance through

more effective selection has significant impact!

Basing selection closely on job requirements will

improve validity. A competency-based approach is

often helpful in making explicit the connection

that is being made between the results of the job

analysis and methods of assessing candidates.

Factors which promote good job performance

such as team working or technical skills are

identified from the job analysis. Assessment

methods are chosen which will measure

candidates’ potential in these areas. Generally the

more assessments used the higher the validity.

Using a variety of assessments will provide

information on all aspects of a candidate’s likely

performance. Concentrating on a single

instrument will tend to identify strengths in a

particular area – but by ignoring other skills reject

candidates who have high potential in other

domains. Assessing people in different ways will

reduce errors caused because people respond

differently to different methods of assessment.

Some people are able to impress at interview –

others may feel too nervous or just not sell

themselves well.

An important consideration is whether the chosen

assessments are suitable for the anticipated

applicant group. If they require knowledge and

experience some will not have had an opportunity

to develop, they can provide biased results. Check

the research literature for evidence of

effectiveness and fairness of the sorts of

instruments you are considering using. Publishers

should be able to supply supporting evidence for

off-the-shelf instruments. It is also worthwhile to

consider carrying out your own research exercise

before committing to an instrument. A study

using incumbents can show whether assessment

results relates to performance level for your job in

your organisation.

The stages of the assessment process should be

balanced to assess the different aspects of the

role in appropriate measure, and not be allowed to

over play the importance of some skills. It is easy

to apply psychometric tests, for example, with

unrealistically high cut-offs. This can have the

effect of supplying a shortlist of very bright

candidates who do not possess sufficient

interpersonal skills for the role.

Another advantage of using a variety of

assessment instruments is that a ‘multiple hurdle’

approach can be taken. The simplest and cheapest

assessments are used first to narrow down the

applicant pool. More resource intensive and time

consuming elements can be introduced at the

later stages when there are fewer candidates to

assess.

Rather than trying to identify the one best of 50

applicants with a single assessment, it is easier to

select the best 5 or 10 in one round and then use

more detailed assessment to select the best of

these. Aim to select between 1-in-3 to 1-in-10 of

those assessed for the next round. It is difficult to

be more selective than this on the basis of the

information generated from a single assessment

round. If you try, decision making may become

rather arbitrary.

It is important to balance the benefit in improved

selection from each additional assessment tool or

stage introduced against the cost of using it.

Moving from one interview to two interviews may

well improve selection. Adding a tenth interview

to a nine interview process will show marginal if

any return. Too many stages are expensive, time

consuming and can put off candidates, whereas

too few may result in very large number

of candidates to assess and very small

selection ratios.

4. Design of the assessment process

6 > Best Practice Series

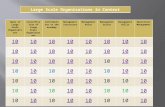

Example

Applications submitted 5000

Pass Application Form Sift 2000

Pass stage 1: Ability Tests and HR interview 800

Pass stage 2: Assessment Centre 200

Best Practice Series > 7

• Estimate the likely number of applicants

• Think about the number of stages needed and put the most efficient and economical stages first

• Work out the likely success rate and the number of candidates to be processed at each stage

(anticipate some drop out by candidates - a spreadsheet can be helpful for this)

• Balance the stages so that your assessments cover the broad array of skills required for the role

• Consider how many assessors you will need and where they will come from - what sort of skills

and training will they need?

• Develop periodic top up training or benchmarking to keep assessors on track

• Find the other needed resources - accommodation, materials, administration and IT support

• Develop a good manual or electronic system for tracking candidates and storing assessment data

• Plan the implementation of the new system carefully making sure you have buy in from all the

stakeholders and enough resources to deal with any teething problems

• Think about how you will judge the success of your selection process, e.g. improvements in time to

hire, cost per hire, staff turnover, offer acceptance level.

Assessment Design Checklist

Technology can be very efficient when replacing

paper processes. It is typically faster and more

accurate than people at dealing with large

applicant numbers. However, when introducing

technology it is worthwhile considering whether to

use a different approach rather than merely trying

to recreate a paper-based system in an electronic

medium.

Technology makes new ways of doing things

possible. It pays to think creatively and question

standard practices when designing an IT system.

Well designed systems can reduce time to hire,

free recruiters from mundane and repetitious

tasks and provide a consistent response to all

candidates. They can also enable more exciting

and effective methods of assessment.

Examples of using IT in assessment

processes include:

• Administering psychometric tools on laptop or

palmtop computer to speed up their scoring

and interpretation

• Using scanners to “read” CVs or application

forms and conduct a first sift

• Tracking, monitoring and driving applicant

traffic through the recruitment processes

• Communicating recruitment information to

HRIS databases, e.g. PeopleSoft, SAP, Oracle

• Allowing candidates to complete and submit an

application form directly from your website

• E-mailing invitations and briefing materials for

an assessment day

• Administering flexible assessments that

adapt to candidates responses, e.g. include

additional questions according to a candidate’s

previous responses

• Using multimedia technology to help applicants

to “visualise” the post they are applying for, or

be assessed using their responses to realistic

situations that they are shown.

The principles of using IT in assessment processes

are not so very different from more manual, paper

based approaches. Indeed the sophistication of

the computerised technology should not be

allowed to distract the user from the function that

it is performing.

5. Use of technology

8 > Best Practice Series

• Check that all suitably qualified applicants

can access the medium, making sure you

have a fallback for those that do not

• Make sure your staff understand how

the system works and get them to try it

for themselves

• Check the assessment is relevant to the

job and of high quality (reliable, valid,

fair, professional)

• Are the instructions and procedures clear

and open to all applicants?

• Are the options and pull down menus fully

inclusive – there is no room on electronic

forms to write explanatory notes

• Is the IT side of the process secure

(physical security, passwords,

encryption etc.)?

• Is the software and hardware robust

and managed by professionals who can

provide support?

• If you are mixing paper and IT media for

different candidates, is there data to show

their equivalence?

• Develop procedures for people with

disabilities for whom the technology

may present a problem.

Assessment Using Technology Checklist

5.1 Internet-Based Assessment

The Internet has been perhaps the most

pervasive influence upon recruitment since the

move to IT recruitment systems. It brings a

number of potential benefits:

• Cheap and immediate 24/7 international

communication – excellent for liaison

with candidates

• Interactive web content – can provide

candidates with a clear picture about the

job and the organisation

• Can deliver innovative and fun content for

attraction purposes

• Direct access to database technology – good

for tracking, sifting and sorting candidates

• Can speed up the initial application

process greatly.

Organisations who are using these systems are

regularly reporting big savings in advertising

fees, travel/postage expenses and reduced

administration. There are however some issues

that need to be considered. The Internet is a fast

changing medium and use does vary significantly

across different international audiences and

sections of society. Hence you need to make sure

what you do is appropriate for the kind of people

you are anticipating will apply.

Best Practice Series > 9

• Make sure your applicants have access and

will feel comfortable using the Internet

• Develop your application to work well with

the lowest specification machine and modem

speed that applicants are likely to be using

(this sets a limit on how sophisticated you

make your web content)

• Pay attention to how user friendly the site is.

Follow WC3 guidelines for accessible websites

www.w3.org/WAI

• Match the design to the typical attention span

of your likely candidates - try to keep

applicants active and engaged

• Check the look of your site using different

browser configurations

• Is the system secure from hacking?

• Develop helpdesk support for candidates who

have problems – ideally this should be 24/7

• Review the robustness of the hosting system

and make sure there are staff available to

deal with problems quickly

• Check the capacity of the site against the

number of ‘hits’ you expect, as large

proportion of candidates are likely to apply

at the last minute.

• Remember that candidates will experience

different background conditions while

completing information on the Internet –

space, noise, disruption etc

• How will you deal with international

applications? What languages are available?

How internationally inclusive are your pull

down menus options?

• The web is a more transitory and informal

medium – consider how this will affect

candidates answers and the way you

assess them.

Internet Checklist

Once the process has been designed, thought

needs to be given to sourcing applicants. It is

important to generate both the required quantity

of applicants but also high quality applicants with

a good proportion who will be suitable for the job.

Even where there is no shortage of applicants it is

useful to consider whether you are attracting the

right candidates. Do they have the range of

qualifications or experience you would like? Is the

range too broad or too narrow? Would candidates

from a different background do the job better or

differently?

Diversity in terms of background, education, age,

experience and other factors can often bring

benefits to an organisation such as innovative

thinking or a better understanding of different

client groups.

Agencies involved in sourcing candidates for you

need to be clear about the type of people you are

looking for. Information needs to be very specific

as recruitment consultants generally take a broad

view of what constitutes a good person-job match.

You are responsible for ensuring that an agency

works to your best practice standards. If you have

policies regarding Equal Opportunities or other

matters, make sure that the agency is aware of

them.

Different recruitment markets have very different

numbers of applicants applying for each vacancy.

Although some organisations find it extremely

difficult to find sufficient numbers of good quality

applicants, there are others that are swamped,

and find it a logistical and ethical struggle to

process them in a fair and efficient manner.

These differences can occur within the same

organisation for different jobs, and even for the

same job over time.

It is also common to find that organisations

oscillate between “attraction” (where the major

effort is invested in generating applications)

and “selection” (where the key focus is

shortlisting candidates down to appropriate

numbers). See the lists below for dealing with

these different scenarios.

6. Recruitment

10 > Best Practice Series

Encouraging Applicants

• Advertise broadly

• Make your advertising fun

• Focus on the positive aspects of the role

• Consider alternate sources of recruits: Web,

community centres, recruitment fairs,

specialist press, radio, customers

• Investigate why candidates do not apply and

address misconceptions or issues

• Be flexible in dealing with candidates

• Make it easy to apply - provide

different options.

Discouraging Applicants

• Target advertising at only the most

suitable applicants

• Use low key advertising

• Make sure applicants understand the negative

aspects of the role

• Require candidates to spend time and effort

on their application form

• Stress rigorous nature of assessment process

• Require candidates to strictly conform

to procedures

• Provide a realistic indication of chances

of success.

Best Practice Series > 11

Recruitment Checklist

• Define the sort of person you would like to attract

• How can such people be best contacted, e.g. What media are they exposed to? What sort of events

would they attend?

• Design your advertising carefully to project the right image. Think about using a focus group to

check its impact

• Provide clear information about the role and the organisation, and make sure your advertising copy

and supporting materials address any common misconceptions or concerns candidates may have

• Prepare an application pack with clear answers to likely questions about the role, the organisation

and the selection process - good information can minimise the resources needed to answer

candidate queries

• Use multiple media, e.g. Internet, brochures etc. to reinforce your brand as a recruiter.

Before beginning to attract candidates, the

assessment procedure must be well planned. As

well as the general issues discussed in Section 4

on Design, each stage in the process places

additional requirements upon the designer. It is

not possible here to cover best practice in

applying all types of assessment procedures.

Other guides in this series look at aspects of using

tests, interviews and assessment centres. Here

we concentrate on the initial sift which raises

particular issues when working with large

numbers of applicants.

It is generally accepted that there are three levels

of administration security possible:

• Open access – the candidate completes a

questionnaire or test with no involvement from

the organisation (there is no control over the

numbers of applicants applying)

• Controlled access – the candidate is invited to

complete a test or questionnaire by the

organisation (the organisation can control

numbers but cannot be certain of the identity

of those applying)

• Supervised – the organisation attempts to

be certain of the identity of the candidate

by supervising them completing the test

or questionnaire.

In general these levels of security are added

sequentially to the process as candidates progress

through it.

7.1 Initial Sifting

Often less consideration is given to the initial sift

than other parts of the assessment process - and

yet this is the stage at which 50-90% of

applicants will be rejected. Thought needs to be

given to the process, the content and who will be

involved. Otherwise you are in danger of rejecting

some of your best candidates without realising it.

Calling for CVs is simple and may make life easy

for candidates who have one ready. However,

sifting on the basis of CVs can be difficult and

time consuming. Not everyone includes the same

information and it is organised in different ways

on different CVs. With large numbers to read this

can make sifting awkward and inconsistent.

Where an application form is being used, it is

worthwhile thinking about how shortlisting

decisions will be made before finalising what

information will be collected. Each piece of

information requested should be relevant to the

requirements of the role and be useful in making

shortlisting decisions. Rather than using a generic

form, it is worthwhile designing a tailored form

providing exactly the relevant information in a

convenient manner.

Where more than one person will be involved in

shortlisting it is important that there is

consistency in the way decisions are made. All

those involved should have a common

understanding of what the positive and negative

indicators for the role are. It is important the

guidelines are explicit - otherwise sifters will

interpret them in different ways. For example, is a

2.2 a ‘good degree’ or only a 2.1 or above? Or

perhaps a ‘good degree’ is one from a better

university or with a particular content focus.

In some cases candidates can look very similar

from their application forms and it is difficult to

be very selective on the basis of qualifications and

experience. With graduate recruitment, most

candidates have only minimal work experience.

High school achievements will be strong enough

to reach university, and perhaps three or four

years old. Final university results will not yet be

7. Assessment procedures

12 > Best Practice Series

available if selection occurs during the candidate’s

final year of studies. In these cases approaches

which generate different kinds of information can

be useful at the sifting stage. These can range

from structured questions based around job

competency areas to ‘biodata’ approaches which

score background data and interests. Research

suggests that these can be very effective

methods of shortlisting when properly applied.

They are amenable to Internet delivery and some

to computer scoring which can increase both

speed and efficiency for large numbers as well as

reducing costs.

Note: SHL continues to be a thought leader in the

area of best practice in the use of online

assessment tools. Further information about our

recent studies on e-assessment can be obtained

from our website www.shl.com/shl/uk.

Best Practice Series > 13

• Check how the different questions relate to

the job requirements

• Produce guidelines/training to

ensure shortlisters are using similar

decision criteria

• Consider the design issues:

• Make it easy for candidates to complete

• Make sure that important information is

easy to see

• Provide space for shortlisters to

document their decisions

• Produce equivalent guidelines for

shortlisting internal applicants or people

who apply with their own CV

• Include a monitoring form so that you can

check for fairness later with this data

hidden from recruiters

• Consider adding other sections or stages

to the process if you need to reduce

applicant numbers further, e.g. online

ability tests.

Application Form Checklist

Assessment processes are designed to meet

organisational needs. The organisation designs

and pays for the assessment – and also pays the

price if the wrong person is appointed. It is easy,

but dangerous, to forget the needs of the

individual candidate within this process. There are

a number of reasons why it is important to

consider how the process will feel from the

candidate’s perspective:

• The best candidates are likely to be sought by

many employers, and they will reject a job offer

if they gain a negative impression of the

organisation through the selection process

• Rejected candidates may well be future clients

– so a positive impression is desirable – and you

may want the best of the rejected people to

apply for another position

• Unhappy candidates will not apply again

themselves and are likely to discourage their

friends from doing so

• There is a moral obligation to treat candidates

with respect

• Unhappy or ill informed candidates are more

likely to contact you with queries – and this can

be a drain on resources

• A disgruntled candidate is more likely to take a

claim of unfairness to tribunal. Even if there is

no case to answer, the management and

professional time required to deal with this

type of case is considerable. The negative PR

involved in such situations is also undesirable.

8.1 Communication

The process will seem fairer to candidates if they

understand what is happening and what to expect.

They will become anxious if they do not hear from

you when they expect. It can be expensive to

continually write to a large applicant pool, but do

consider the implications of not acknowledging

application forms or sending out rejection letters

in terms of the company image and the number

of impromptu queries that will be made. Try to

think about ways of reducing the workload for

you, e.g. ask the candidate to fill in their address

on an acknowledgement card as part of the

application process. Internet-based systems can

be designed to send automatic acknowledgement

e-mails to candidates.

In large assessment processes the interaction with

the candidate will generally be less personalised.

Recruiters may not have an individual relationship

with each candidate but rely mainly on

standardised communications. For this reason it is

important to invest in making your standard

communication as informative as possible. This

applies both to the content of the information and

also to the style. The tone of a letter will tell the

candidate a lot about the company culture. Think

about how formal it should be and how

encouraging.

Technology can make a standardised letter seem

more personalised by allowing you to tailor letters

for different categories of candidates. A friendly

but professional tone, some explanation of why

the system is as it is, and sensible anticipation of

candidate needs can leave candidates feeling

more comfortable and reduce the number of

queries those managing the system need to

deal with.

8. Balancing individual candidateneeds and organisational costs

14 > Best Practice Series

• “we anticipate a large number of

applications and want to have the time to

read each one carefully”

• “the next stage of the procedure if you are

shortlisted will be……… and this is likely to

take place………”

Example Promises

8.2 Feedback

A difficulty with large scale assessment is

providing feedback for many candidates because

of the resources required. Feedback helps

candidates to see that the information they

supplied was fully considered and that there are

clear reasons why their application was, or was

not progressed. Where psychometric instruments

are used feedback should be provided wherever

possible. Unlike more straightforward procedures

such as the interview, it is difficult for candidates

to know how well they have done or what their

answers signify.

Telephone feedback is often simpler to provide

than a written report. Putting the onus on the

candidate to request it means you don’t need to

spend time with those who are not interested.

Another approach, where computer-based

assessment is used, is to design ‘expert

systems’ which can generate a written report

for the candidate explaining their results in an

appropriate manner. While this should be

supported with a helpline, a well written report

alone will suffice for many candidates and they

may well appreciate the personal learning it

allows from the selection process. The Data

Protection Act (see Section 12, page 19) places

a requirement to provide, upon request,

written information on any data that is held on

a candidate in a searchable database

(computer-based or otherwise). It is thus

important that you should build in some way of

dealing with such requests in any case.

Best Practice Series > 15

• Provide a clear and realistic description of the role (including the negative parts) so that

candidates can decide for themselves if they really wish to do it

• Make sure your recruitment material (website, brochure, assessments) reflects your brand as

an employer

• Provide clear information about the process for candidates - what it entails, how long it will

take etc.

• Provide information so that candidates can prepare themselves for assessments, e.g. think what to

say at interview, practice answering test questions

• Make sure the logistics of the process allow you to honour any promises made, e.g. about when

you will be in touch

• All interactions with the candidate should be professional, e.g. the person answering a telephone

must be able to answer candidate queries, Internet-based systems should function correctly

• Plan how you will offer feedback at each stage, e.g. face-to-face, telephone, e-mail, expert system,

subcontracted, and make sure appropriate resources are available

• When will feedback be given - a short delay suggests to candidates that the decision has been

taken carefully, a long delay may make the feedback less useful.

Candidate Perspective Checklist

Large scale assessment processes will almost

certainly be administered by a number of different

users, who are likely to change to some extent

over time, and who may be operating in different

locations simultaneously. It is important therefore

that these individuals have some way of checking

that their activities are compatible with each

other. A policy for designing and administering an

assessment process is thus strongly

recommended as a template against which they

can operate. The SHL booklet Guidelines for Best

Practice in The Management of Psychometric

Tests covers writing a policy and details a number

of core components that might be included.

A consistent policy is particularly important in

dealing with ‘special’ cases. Where a system is in

large scale operation, the frequency of ‘special’

cases should be anticipated and provision made to

deal with them. This would include;

• Requests for accommodations by candidates

with disabilities. (See Guidelines for Best

Practice in Testing People with Disabilities)

• Appropriate procedures for candidates

who miss deadlines due to illness or

other circumstances

• Policy on requests for retesting, and

repeat applications.

Detailed consideration of these issues should give

users the guidance that they need to apply

processes in a truly consistent and high quality

manner. This should help to ensure that the

process remains professional, helping to ensure

that the organisation’s image remains

untarnished, and that it continues to be seen as

an attractive place to work.

9. Need for organisational policy

16 > Best Practice Series

• Include sections on each part of the

process, data management etc.

• Describe training requirements for staff

• Check that you have covered the different

types of special cases that are likely to

arise - candidates with disabilities, illness

before or during the assessment, reuse of

assessment data if candidates reapply

• Check regularly that the policy is being

carried out and review its content from

time to time.

Policy Checklist

The nature of large scale assessment processes

means that the same event may need to be rolled

out several or indeed hundreds of times, often

under difficult time and resource pressures. The

risk here therefore is that over time the carefully

engineered process can become watered down

and flawed. It is therefore prudent to audit such

processes on a regular basis to ensure that they

are being operated as originally intended.

10. Maintaining standards

Best Practice Series > 17

• Check that Best Practice in use of assessment technologies is being followed

• Make sure that recruiters continue to work to agreed standards. Ensure refresher training is

available and taken up by assessors

• When there is staff turnover, make sure new recruiters and assessors understand the process well

and have received relevant training

• Check for changes in the applicant group that might require revision of the process. This may

happen when the process is applied for a different role or when there are changes in economic or

other factors

• Check whether information about the process is becoming available to candidates. Past candidates

pass on their experiences to new candidates, sometimes in a wholesale manner, e.g. via a website

such as www.vault.com

• Check that materials are not outdated, unprofessional or inappropriate

• If key stages in the process are subcontracted or outsourced check that external agencies are

operating appropriately.

Maintaining Standards Checklist

It is sensible to evaluate the effectiveness and

fairness of any selection procedure. However, this

becomes imperative with a large scale process,

where even a small degree of unfairness can

affect a substantial number of people. The high

profile nature of large processes can make it more

open to challenge and larger organisations are

often held to higher standards of practice by

tribunals and others.

Issues should be addressed from both a

qualitative and a quantitative perspective.

Qualitative evidence would include measuring the

satisfaction of line managers and trainers with the

competency of those appointed. But you should

also check the statistical evidence that the system

is identifying the best performers by looking at

the relationship between performance on the

different selection exercises and later on the job.

This can show whether all elements of the

selection procedure are useful and effective.

Monitoring the success rates of members of

different groups is also an important part of any

review. Consider changing or adapting elements

which are associated with substantial adverse

impact. This is not of itself illegal but you must be

sure you can justify this part of the process in

terms of its relevance to job requirements. See

the SHL Guidelines for Best Practice in the Use of

Personnel Selection Tests for further details.

11. Monitor fairness and effectiveness

18 > Best Practice Series

• Collect data (monitoring) about how

the different stages of your process

are working

• Does your ethnic classification comply

with best practice?

• Review monitoring data regularly

• Does the system run smoothly from an

administrative perspective? What can be

done to improve it?

• Check with assessors that the information

generated during assessment is sufficient

to allow the differentiation between

candidates that is required

• Follow up the selected candidates to see if

they learn their roles quickly, perform well

on the job and assimilate into the

organisation easily.

Monitoring Fairness Checklist

The aim of the Data Protection Act is to

safeguard the individual against the misuse of

information held in computers or other

database/filing systems. In the assessment

context this means that files on individuals,

whether electronic or paper, should be:

• Securely stored

• Access to paper records should be

restricted to those involved in the

recruitment process. Data should be locked

away or otherwise secured. Computer files

should be password protected

• Only used for the intended purpose

• The data should be appropriate for use in

selection and candidates should be asked to

agree to the storage and use of their data

for this purpose. They should be informed of

any other uses to be made of the

information they supply and for how long it

will be kept

• Deleted after a reasonable period determined

by the organisation

• Accessible to the individual

• Under the act, individuals can request a

written report of any data pertaining to

them that is held. They have the right to

request corrections of any inaccuracies.

Even if you dispute the inaccuracy you

should make a note on the file that the

candidate does not agree with the original

statement. Such requests should be

complied with, within 40 days and you may

charge up to a £10 fee.

Particular care should be taken regarding

‘sensitive information’. This would include any

record of the person’s ethnic origin, e.g. if

collected for monitoring purposes (unless

collected anonymously), as well as information

relating to the person’s health, trade union

membership or religious views.

12. Data protection act

Best Practice Series > 19

• Check whether you need to be registered

with Information Controller -

www.dataprotection.gov.uk

• Develop a policy for how you acquire, store,

access, check and delete personal data

• Consider both electronic and paper

systems - all are now covered under the act

• Ask candidates to sign an agreement

regarding your holding and processing

their data

• Check that assessors and line managers

are not retaining copies of selection data.

Data Protection Act Checklist

These Guidelines were written by James Bywater and Helen Baron.

References

SHL Guidelines for Best Practice in the Use of Job Analysis Techniques

SHL Guidelines for Best Practice in the Management of Psychometric Tests

SHL Guidelines for Best Practice in Testing People with Disabilities

SHL Guidelines for Best Practice in the Use of Personnel Selection Tests

SHL Guidelines for Best Practice in Selection Interviewing

SHL Guidelines for Best Practice in the use of Assessment & Development Centres

All Best Practice Guidelines can be downloaded, free of charge, from the SHL website. For further

information visit: www.shl.com

Relevant Websites

www.shl.com/shl/uk

www.onrec.com/content2/default.asp

http://ri6.co.uk/ri5/news_index.html

www.peoplemanagement.co.uk/default.asp

www.intestcom.org/

www.dataprotection.gov.uk/

http://recruiter.totaljobs.com/recruiterzone/info_research/index.asp

www.ukrecruiter.co.uk/new.htm

www.psychtesting.org.uk

www.ilogos.com/

www.vault.com

www.w3.org/WAI/

www.dataprotection.gov.uk/whatsnew.htm#Employ

Glossary

• Adverse Impact – A selection process has adverse impact when proportionately fewer of one ethnic or

gender group can meet the criterion that has been set

• Competency - A skill that is important for a job, usually described in behavioural terms

• Designer – The party(ies) who decide which selection stages will be used, and how they will be used in

the process

• Equivalence – The extent to which results of tests are comparable across various modes of

presentation, such as paper & pencil vs. computer-based

• Monitoring – Organisations should collect and review data to examine the effects of the processes that

they have implemented

• Selection Ratio – The ratio of the number of people selected to total applicant pool size

• Validity – The extent to which an instrument “works” i.e. measures what it is designed to measure, and

is related to performance in the job.

13. Further information

20 > Best Practice Series

Guidelines for Best Practice in the Use ofPersonnel Selection Tests

Whilst SHL has used every effort to ensure that

these guidelines reflect best practice, SHL does not

accept liability for any loss of whatsoever nature

suffered by any person or entity as a result of

placing reliance on these guidelines. Users who have

concerns are urged to seek professional advice

before implementing tests.

The reproduction of these guidelines by

duplicating machine, photocopying process or any

other method, including computer installations, is

breaking the copyright law.

SHL is a registered trademark of SHL Group plc,

which is registered in the United Kingdom and other

countries

© SHL Group plc, 2005

United KingdomThe Pavilion

1 Atwell PlaceThames Ditton

Surrey KT7 0NE

Client Support Centre: 0870 070 8000Fax: (020) 8335 7000

UK

BP

7V

1U

KE

339

4