BEBOP SPACES: MASTER TAKE€¦ · Bebop SPACES is inspired by the performance entitled Leap Frog,...

Transcript of BEBOP SPACES: MASTER TAKE€¦ · Bebop SPACES is inspired by the performance entitled Leap Frog,...

-

BEBOP SPACES: MASTER TAKE

Bennett R. Neiman1

1. Texas Tech College of Architecture, Lubbock, Texas

Abstract

Bebop SPACES is inspired by the performance entitled Leap Frog, by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. The project is a series of architectural improvisations or “takes” that spontaneously transpose, manipulate, and articulate various links, connections, joints and transitions present in jazz music. The improvisations start with an underlying source that is developed into an extension line network. This vehicle is played as a series of chromatic encodings which take multiple trajec-tories. The bebop SPACES video is an attempt to represent the tonality of this poetic design process as actions instead of words. Initially, the designer records the live action on the computer screen. The video footage is sped up and edited into a rough demonstration, set to a short out take track of Leap Frog. Through illusory animation and time compression, the video represents what is occurring in the mind of the designer as he creates these works. A second take is created with newer, more extensive footage, as a mostly intuitive and subliminal response to the master take of Leap Frog. The main devices used are speed and repetition with slight variation. The third take attempts to consciously and precisely link the events of the visual compositions to the im-provisational structure of the music, building on the knowledge gained from the previous intuitive video takes.

1. Call and Response: A Design Performed

These forms emit and listen. -Le Corbusier on visual acoustics.

Bebop SPACES is inspired by the performance entitled Leap Frog1, by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. The project is a series of architectural improvisations or “takes” (fig.1) that spontane-ously transpose, manipulate, and articulate various links, connections, joints and transitions pre-sent in jazz music.2 Designers usually establish a concept, a schema, or a partí to drive a design process. According to jazz terminology, the tune (vehicle) is the short little musical idea that you can recognize and hum as a basis to motivate subsequent improvisation.3 Common in both popular and jazz music, the first chorus sets up an underlying AABA structure. The tune is stated within the first A-section. Variations of this vehicle might be repeated several times within a typical AABA chorus structure. The B-section acts as a bridge or transition. The B-section can be seen as a related, but different, variation on the tune. The chorus concludes with a return to an A-section, restating the original tune.

In Leap Frog, Parker (on alto saxophone) and Gillespie (on trumpet) push the boundaries of this common AABA structure. According to the album Bird and Diz liner notes, “There is no theme statement after the intro, Parker’s solo follows immediately.”4 This establishes a vehicle within itself that is followed as a series of responsive, back and forth solos between Parker and Gillespie throughout the entire song. Gillespie plays in response to improvised phrases set up by Parker.

Neiman-1

-

Then Parker responds to Gillespie’s response. It is a conversation, or perhaps an argument. It is a call and response exchange where improvisation follows the underlying structure presented in the original solo as an on the spot dialog between the two musicians. As the song proceeds, each subsequent exchange becomes further removed from the original vehicle. At a certain point Parker and Gillespie bring back the tune in the final moments of the song, this time in response to a third party, the drummer, Buddy Rich.

In recorded music the group usually has to play the song in several takes. The first take might be the best one, or they might not get it right until the last take. During the process they might get tired, frustrated, or irritated and then something magical happens. Because of its complexity and speed, Leap Frog required numerous takes. One of those takes was declared the master for the original 1956 album release. Subsequent CD releases in 1986 and 1997 include the alternate takes and other out takes. Today’s listeners can compare and contrast the relative qualities of these variations against the master take.

2. Extension-line Network

The bebop space improvisations start with the construction of a simple tracing, that in effect, translates the bit-mapped information of the underlying source image (fig. 2) into vectors. (fig. 3) A second series of studies requires that every orthogonal element generates an extension line in both the horizontal and vertical orientations. The non-orthogonal elements work against these extension lines. The beginning is somewhat literal, but soon there is a realization that certain elements need to be adjusted and refined in various ways. For instance, if an element is so close to being orthogonal, it might as well be orthogonal. Correcting this flaw in the line drawing gives more meaning to the elements that are obviously angled or curved.

A period of practice precedes an established direction. Numerous variations of the extension line drawings are generated before arriving at the refined base structure. There is a negotiation be-tween individual moves in the drawing, and the reconciliation of figures relative to other elements and the extension line network. (fig. 4) Ultimately, it is a search for the logical arrangement and articulation of objects defining spatial structures within the structure.

3. Improvisations: Chromatic Encodings

The underlying extension-line vehicle is played as a series of chromatic encodings that take mul-tiple trajectories. (fig. 5) Selected elements and regions are filled with different colors. Each color type (red, blue, black, and gray) represents subliminal systems, sometimes metaphoric, other times structural. The chromatic encoding process does not follow a strict recipe or formula. It is an exploratory search to define primary, secondary and tertiary precincts within the given underly-ing order. There are numerous experiments produced moving from the original source image to the base extension line drawings to the chromatic encodings. These studies test orientation con-stants and variables. Other drawings explore figure and ground. (fig. 6)

The work proceeds for a certain period of time, such as fifteen minutes, or a couple hours, or until a sense of balance occurs. At that moment, the improvisation is printed and declared as a take. Then it is put away. (fig. 7) A new one is started from memory. No attempt is made to replicate a previous improvisation or to consciously redesign it. Each subsequent generation is started en-tirely from memory with the underlying drawing as a base. (fig. 8)

These studies have aspects of minimalism. At the same time there is an illusory condition that has an abstract representational quality. It is encoded space, not literal space. You read relation-ships among individual elements. It represents reciprocal notions of plan and section. Within the complexity it is open ended. There is a strong architectural quality to it. Although it appears to be

Neiman-2

-

very flat, it also gives a sense of depth because of the strength of line weights and different densi-ties of color and shade.

After working on four or five of these improvisations in a row, previous key moves and patterns start to repeat themselves instinctively as variations within the structure, in slightly different ways. These improvisations are performed in as many takes as necessary until a satisfactory level of ordering is established. But sometimes something strange happens. The successful ordering oc-curs in a single take. It is difficult to improvise immediately. You can usually improvise better after you have been playing for a while. If you are practicing, and then draw upon that experience, then in effect, you are warmed up.

4. Video Improvisations

The bebop SPACES videos attempt to describe the tonality of this poetic design process as ac-tions instead of words. Initially, the designer wanted to perform a real-time live demonstration of how the drawings were actually created. To the designer, these actions are liberating and exhila-rating, as the pressure to make quick, on the spot decisions is accomplished. After testing this procedure, it became apparent that to someone watching this, it was the exact opposite. In re-sponse to this disappointing realization, the designer decided to video record the action on the screen as he created a composition. The footage was subsequently sped up and edited into a rough demonstration, set to a short out take track of Leap Frog.

This first presentation was quite effective judging from the audience response.5 A second take was created with newer, more extensive footage, as a mostly intuitive and subliminal response to the master take of Leap Frog.6 Through illusory animation and time compression, the video rep-resented what was occurring in the mind of the designer as he created these works. The main devices used were speed and repetition with slight variation. Several key events corresponded with the music.

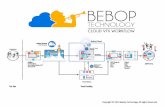

The third take (cast in high definition digital video) attempts to consciously, build on the knowl-edge gained from the previous intuitive video takes. To supplement the intuitive and subliminal responses seen in the initial takes of the bebop space videos, the underlying structure of Leap Frog (fig. 9) is extensively analyzed prior to the the construction of the third take. The analysis precisely identifies key improvisational moments in the music, linking them to the visual events of the digitally recorded compositions.

The improvisational making and the recording process of the performance are seen as equal. Each drawing performance happens in the moment, but at the same time it is based on prior study and thought. Each take decodes architectural space. It is a disciplined act of order and variation on a theme. Each improvisation has intention. It defines structures within a structure. It uses a geometrical arrangement of objects articulating constant and variable events. The Bebop Spaces video represents a process that allows the designer to extract forms and spaces from two-dimensional drawings that have three-dimensional implications. It is a series that begins with an idea about structure. These constructions begin simply and grow with compulsion. The complexity is discernible. The structure itself is manipulated and varied, exploring the edges of rules. Variables are layered on top of the overall constant structure. The playing is a non-premeditated act. It is about working in the moment and in the present. In that respect the proc-ess is real or material.

5. Call and Response: Performer and Audience

Bebop spaces is about a construction process. It asks the question of improvisation as a design process. Access to the detail is in the richness of the interpretation. It becomes a question of scale. The designer can interrupt the process at any time to extract ideas into three dimensions. It

Neiman-3

-

is seductive and at the same time it provokes you into what it might be or what can be read. (figs. 10, 11, 12)

The video is a recording device for an architectural design performance. In order for us to play and enjoy the mechanism, to make the sound, the audience must listen and watch it. When you begin to read it, you begin to improvise. This is because there are infinite interpretations. The lis-tener has to improvise. It is not just the recording itself that is improvised, but also the act of read-ing. The viewer, as a participant, begins to improvise as much as the performer. Similar to a mas-terpiece jazz improvisation, you cannot talk about the performance as effectively as the perform-ance itself. You must experience the composition to appreciate it. You must participate. It is al-most like a mirror.

This project is done as an accumulative process. Rules similar to those established for the stu-dents in an analogous studio are used as an initial basis. However, many of the rules set up for the students are broken. Most of the students would never attempt to bend the rules to this level. Usually what happens is that if the student wants to break a rule, the student usually asks for permission. But if permission is asked, it is summarily denied. If you have to ask, then you are not really improvising. If you go ahead and do it without asking, then, after the fact, you can evaluate how it turned out. If it is good, then who cares if you broke the rule. What is an interesting issue is that when you improvise, you don't ask for permission because if you ask, then there is a separa-tion between you and the art of doing it. Therefore you are not improvising any more. You are thinking too much. In this game, there are strict rules but at the same time it appears very loose. This cannot come out of the intellect or rationality alone. The rules are being broken all of the time, not as a contradiction, but as a tension among the rules. It has the appearance of being strict, but in fact, it isn't strict at all.

...after a while he might bring in the script and we would start working on the script. We would do the lines over and over and over again. Having been a child actor, of course, I knew my lines, so now I was really bored because I would have to do these lines over and over again. By the end of our meetings he would throw improvisation in and that was, I think, a really good lesson. Because I suddenly learned improvisation was about knowing the text so well that you could deviate from it in a meaningful way, as if you had been living this conversation, and always find your back to the text. That's a lesson that most young actors don't really get...7

-Jodie Foster

Neiman-4

-

Figure 1. A film moment for the Bebop Spaces Video Take 2, November 2002.

Neiman-5

-

Figure 2. Source Image - Analog-digital crystals are constructed from the recap-tured video material. These studies combine and accrue as an aggregation of crystals, stretched and compressed, repeated and varied.

Figure 3. Vector tracing of the source image.

Neiman-6

-

Figure 4. Reconciled tracing and underlying extension-line network.

Neiman-7

-

Figure 5. Chromatic encoding in process.

Neiman-8

-

Figure 6. Figure-ground encoding.

Neiman-9

-

Figure 7. Chromatic Encoding - Schema A, Take 1.

Neiman-10

-

Figure 8. Chromatic Encoding - Schema A, Take 4.

Neiman-11

-

Figure 9. Leap Frog analysis - precisely mapping the musical events in prepara-tion for the video Bebop Spaces: Master Take.

Neiman-12

1

parker solos

2

b-sections

gillespie solos

3

trade of fours: p-gintro codatrade of fours: r-p-g

4 5

rhythm connectors

rich solos

6

-

Figure 10. Chromatic Encoding - Stage 4, Take 30.

Neiman-13

-

Figure 11. Chromatic Encoding - Stage 9, Take 4.

Neiman-14

-

Figure 12. Chromatic Encoding - Stage 9, Take 10.

Neiman-15

-

6. References

[1] Composition by Charlie Parker. Personnel: Charlie Parker (alto saxophone); Dizzy Gillespie (trumpet); Thelonious Monk (piano); Curly Russell (bass); Buddy Rich (drums). Producer: Norman Granz. Recorded in New York, New York on June 6, 1950.

[2] Neiman, Bennett. ‘Bebop Spaces’. Proceedings of the 2006 ACSA Annual Meeting, Salt Lake City, UT.

[3] Coker, Jerry, Listening to Jazz. Prentice-Hal, Inc. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1978.

[4] Granz, Norman and James Patrick, Liner Notes from Verve's Master Edition of Bird and Diz, Polygram Records, Catalog Number: 521436, ASIN: B0000047D3, July 29, 1997.

[5] Neiman, Bennett. ‘Design Performance: Improvisation and Speed’, 2002 West Central Re-gion ACSA Conference, College of Architecture, University of Nebraska, Lincoln. presenta-tion.

[6] Neiman, Bennett. ‘Bebop Space/Leap Frog’, Proceedings of the 2002 Western Region ACSA Conference, California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, pp. 129-132.

[7] Comments on improvisation and acting lessons from Robert Deniro during the filming of Taxi Driver, transcribed from an interview on Fresh Air from WHYY with Terry Gross. June 17, 2002.

Neiman-16