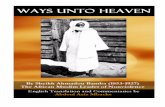

BEAVER WAYS - LA84...

Transcript of BEAVER WAYS - LA84...

BEAVER WAYS

By FRANK H. RISTEEN

drawings by tappan adney

T is early in April in the heartof the still New Brunswickwilderness. From the outerworld of sunshine and open

fields the snow has departed forthe most part and spring’s

balmy air is vocal with the rushand murmur of l i t t le hi l ls ide

streams, while the big ones in the val-leys fret and fume to be relieved of

their icy fetters. But how is it here in theshadowed depths of the virgin woods, wherethe syren voices are the last to be heard?The snow is still five or six feet deep on thelevel; the nights are nearly as cold as in mid-winter, promptly undoing the feeble effortsput forth each day by the northward march-ing sun. The latter has only sent out hisskirmishers as yet; soon there will come theearnest shock of battle when the chill bat-talions of the frost king will yield the fieldsullenly to the ardent attack of his ancientfoe.

Up the sunken snowshoe path that leadsto a homely trapper’s shanty two men walkwearily. They are laden with furs they havetaken that day from a line of traps abouteight miles in length, and are leg-wearyfrom their long struggle with the cloyingdrifts. One of those men is Henry Braith-waite, the famous woodsman, who has spentall his days in the forest; the other, a youngamateur sportsman, whose love for thewoods is sufficient to induce him, as a mat-ter of friendship and recreation, to sharewith the professional the toils and trials ofthe trapping season. That evening, as the

camp-fire roars cheerily, telling with a thou-sand fiery tongues its tale of triumph to thesurrounding chill and gloom, the elder man,in response to his companion’s questioning,discusses freely the subject of beaver ways.

“Beavers are not as numerous over theprovince generally as they were twentyyears ago, but on my own ground they areabout as plentiful as ever, for the reasonthat I have always made it a point to leavea sufficient number every year on the dif-ferent streams to keep the stock replenished.The trapper who finds a beaver family andnever lets up until he has wiped them allout is pursuing a very short-sighted policy.A female beaver will bring forth from twoto five kittens each spring, and I haveknown them to have six, in one case seven,in a litter. In this country the kittens areborn the latter part of May or the first ofJune. The animals are now more numerousin Northumberland and Restigouche thanany of the other counties. They would benumerous in Gloucester, Madawaska, andVictoria, but are followed up too closely bythe Frenchmen, who never think of givingthem a chance to breed. In the southernand western counties very few are now tobe found. The pelts at present are worthabout $2.50 a pound. They vary from halfa pound to two pounds in weight, the aver-age being about one and a quarter. I gener-ally bring in from thirty to sixty skins in aseason. Most of these go to the Londonmarket; some of them to Montreal. Theage of the beaver makes very little differ-ence with regard to the quality of the fur.

668 Beaver Ways

Three and four year olds are about the best,as the skins are more pliable. The drop inAlaska seal has brought down the value ofbeaver, because the latter is used to coun-terfeit the former. After a beaver skin hasbeen plucked and dyed to resemble seal ittakes an expert to tell the difference.

“A good many stories are told aboutbeavers by people who are not well in-formed. For instance, it is claimed thatthey use their broad, scaly tails as trowelsto plaster their houses or dams. As a matterof fact, they simply keep lugging up mudand tramping over it, and that is all theplastering that is done. Then, again, it isstated that they only work at night. I haveoften seen them working in the daytime,especially in the spring of the year, when itfreezes too hard at night for them to cuttheir wood. I have known them to comeout of their houses at eleven o’clock in theforenoon, but it is usual for them to appearat three o’clock and work till dark. TheIndians, and some white men, take advan-tage of this and lay in wait to shoot themwhen they show up. On warm nights in theearly autumn they are not apt to be seen inthe daytime. For shooting a beaver in thewater the shotgun is preferable to the rifle.Only about half of the animal’s head showsabove the surface, and as he is nearly alwaysunder full head of steam, it is hard to stop

him with the rifle. If you miss your beaverhe up-ends and dives like a shot, his broadtail striking the water like a side of soleleather. I believe his object in spanking thewater is to put the other beavers on theirguard.

“In some respects the cleverness of thebeaver is overrated. He is certainly a verygood, clean workman in the mason and car-penter line, but is far easier to trap than afox or a fisher. When you are laying forhim with a gun all you have to do is to keepperfectly still, and he will swim right up toyou, but the slightest whiff of human scentwill send him to the bottom.

“Beaver dams are not always built ofsticks and mud. I have seen four of them builtentirely of stone. At Beaver Brook Lakethere is an old stone dam about forty rodslong. When this dam was first made itprobably was cemented with leaves andmud; but this soft material washed outafter a while without materially loweringthe dam, and when a new family of beaversfell heir to it, they had water enough therewithout having to raise the dam. The beaveris a great worker, but he likes to loaf thesame as any one else when he has a chance.For instance, when he can find an oldlumberman’s dam it is a regular windfallfor him. He goes right to work and plugsup the old gateway, and soon has a splendid

“Swimming down the canal with a tree five times his own weight in tow.”

“If he could get hold of you with histeeth, he would almost take a legoff.”

fit-out. It makes him fairly grin tostrike such a snap as that. But I haveseen beavers that didn’t seem to havegood horse sense. They will under-take to build a dam in a place where it willbe carried away with every freshet, whilewithin ten rods of it there is a good, safe site.Sometimes they will pick out very meanplaces for food and will nearly starve in thewinter, though there is plenty of good poplarand birch not a quarter of a mile away.

“Some people who write stories for thepapers say that what are called bank beaversare lazy old males that have been forced outof the house by the rest of the family be-cause they wouldn’t work. I wonder whatkind of a spy-glass the man had who sawthis taking place. Perhaps he was a mind-reader who could figure out what the beaverswere thinking about. Bank beavers are notalways males by any means. I have trappedfemale bank beavers with their kittens. Thefact is that when beavers take to the bankit is because there is so much water therethat they don’t need a dam, or because thereis no chance to build a dam. That is whyyou find the bank beavers mostly on lakes,or large rivers, which they are unable to dam.

“A full-grown beaver will weigh from thirtyto forty pounds. I have caught a good manyscaling over forty pounds, and have been toldby very reliable people that sixty pounders

have been taken. Ithink the beaver, if he

could only keep out of thetrap, would live to a ripe old

ago. His growth is very slow,yet he sometimes reaches a re-

markable size, with every sign offextreme age. I feel safe in saying

that he is liable to live to be twenty-five or thirty years of age. The fur

of the beaver is at its best in the winterand early spring. The outer and longercoating is coarse and glossy, almost black incolor; the under coat is very thick and silky,nearly black on top and silver-gray under-neath.

“The beaver is really a sort of automaticpulp-mill, grinding up almost any kind ofbark that comes his way. I once meas-ured a white birch tree, twenty-two inchesthrough, cut down by a beaver. A singlebeaver generally, if not always, cuts the tree,and when it comes down the whole family fallto and have a regular frolic with the bark andbranches. A big beaver will bring down afair-sized sapling, say three inches through,in about two minutes, and a large tree inabout an hour. The favorite food of theanimal is the poplar, next comes the cherry,then the balm of Gilead. They are fond ofall kinds of maples, and will eat cedar, hem-lock, or spruce. In some places they feedprincipally on alders. They also eat theroots of many kinds of water plants. Whenfood is scarce they will consume the bark ofthe largest trees.

“They commence to build their houses andyard up wood for the winter in September;sometimes, however, as early as August, and

670 Beaver Ways

sometimes as late as October. They drag in have cemented the mass the house is well nighthe wood from all directions to the pond, impregnable. It is perfectly air-tight, andand float it up as near as they can to the front being steam-heated by the beavers must beof the lodge. There are usually two doors very warm and cosy in the coldest weather.to a beaver house, and a favorite place for Old beavers build large houses, work system-them to pile their wood is between these atically, and go in for comfort generally.openings. A large quantity, however, is left “Each beaver places his bed neatlyout in the open pond, very little of which is against the inner surface of the wall. Hisavailable for consumption, because when the bedding is composed usually of wood fibersshallow pond freezes up the beavers are only stripped line, about like an Indian’s broom.able to reach what is below the ice. The In the case of lake beaver, with whom wood

is scarce, blue joint grass is used for bed-ding. This is taken out frequently and a

fresh supply brought in, forthe beaver is a mostcleanly animal, and his

couch is soon fouledby his muddy occu-

pation. Occasion-a l l y a b e a v e r

house is foundwith a root or

stump run-ning up

“They can be captured by making a small break in the dam and setting atrap where they will come to repair the leak.”

size of the house, as well as of the woodpilestored in the pond, depends on the size ofthe family. An average house, which iscircular in shape, will measure about twelvefeet in diameter and stand from three to sixfeet above the surface of the water. I haveknown them to be as large as sixteen and assmall as six feet in diameter. The walls areabout two feet thick, and, even without theaid of winter’s masonry, are strong enoughto support the weight of a full-grown moose.After the rains and frosts of early winter

through the center, around which the bedsare ranged.

“The two outlets from the lodge are builton an incline to the bottom of the pond. Ithink the intention is that if an enemy comesin one door the beavers can make out theother. The mud with which the roof isplastered is mostly taken from the bottomof the pond close to the house, sometimesleaving quite a ditch there, which is handy, asgiving the beavers room to move about whenthe ice gets thick. As the ice freezes down

Beaver Ways 671

to the bottom the beavers extend a trenchfrom this ditch out farther into the pond toenable them to reach their food. This trenchis sometimes ten rods in length. They willoften cut a canal about three feet wide fromone lake to another, if the intervening groundis barren and the surface level. Sometimesthey will excavate an underground canalbetween the lakes. If the house is on a lakeand there is a wide strip of barren betweenthe house and the edge of the woods theywill cut a canal clear up to the edge of thewoods so that they can float their stuff down.To see a beaver swimming down the canalwith a tree five times his own weight in towis an amusing sight. He has a good deal thesame look of mingled triumph and responsi-bility on his face as the man who is lugginghome his Thanksgiving turkey.

“It is very seldom that the house is lo-cated on or near the dam. Beaver damsvary a good deal in height, according to theshape of the bank and the depth of water,seldom, however, measuring over seven feet.They are often eight or ten feet wide atthe base, sloping up to a width of from oneto three feet on top, and are usually water-tight. They are very firmly constructed andwill lust for years, as a rule, after the beav-ers have left them. Where beavers have sel-dom been disturbed, they can be capturedby making a small break in the dam andsetting a trap for them when they come torepair the leak. But where they have beenmuch hunted—and they are mostly all prettywell posted those days—this plan is a poorone. The beavers will promenade on top ofthe dam and smell around the trap to seewhat is the matter, and when you visit thetrap you are liable to find in it nothing buta bunch of sticks. A beaver colony may usethe same dam for a number of years, espe-cially when it is at the outlet or inlet of alake, but they will usually build a newhouse every year. I think they do this onthe ground of cleanliness, on which pointthey are very particular.

“As compared with the otter or mink,the beaver is a very slow swimmer. Hisfront legs hang by his sides, and he usesonly his webbed hind feet. It is easy tocapture him with a canoe if you can findhim in shoal water. He is a most deter-mined fighter, but clumsy and easy tohandle. If he can get hold of you with histeeth he would almost take a leg off—soyou want to watch him sharply. The proper

place to grab him, with safety to yourself, isby the tail.

“The only enemy the beaver really has tofear is man. The bear and the lynx stillhunt him sometimes, but not with muchsuccess. I have known a bear to go downinto four feet of water and haul a beaverout of a trap. The lynx occasionally catchesa small beaver on the bank, or in a shallowbrook, but a full-grown specimen is toomuch for him to handle. The intelligenceof wild animals in some respects is superiorto that of men. They never have a swelledhead; never bite off more than they cancomfortably digest. Each fellow knows whathe is able to tackle and get away with with-out injuring his health. The bear has toomuch sense to tackle the porcupine, and allhands line up to give the skunk the rightof way.

“As soon as the lakes and streams openin the spring the old males, and all the twoand three year olds, start off on a regular ex-cursion and ramble over the brooks and lakesfor miles around, the old females remainingat home to rear their young. In fact, themother beavers remain at home all summer,while the rest of the tribe range about untilSeptember, when they commence to club to-gether again. The kittens generally remainwith the mother for two years. When theyare three years old they mate and start offon their own hook. You can always tell thenewly wedded couple by the small, snughouse they build. They seem to be very de-voted to each other, but I have noticed onepoint about the young she beaver that isvery human. If the trapper comes along,and her mate is taken, she goes skirmishingas soon as possible for another husband.

“Near the root of the beaver’s tail areglands which hold a thick, musty substancecalled the castoreum, which is used by trap-pers to scent their bait. When I want toshoot a beaver I get out my bottle of cas-toreum and pull the cork. The beaver willswim right up within range as soon as hecatches the scent. When trapping in thefall, which I seldom do, I generally daub alittle of the substance on a dry stub or snaga few yards away from the shore. The trapis set about three inches under water, wherethe beaver climbs up on the bank, a bunchof poplar being generally used for bait.When trapping in the winter you cannotuse the castoreum, as the trap must be setunder the ice, where the scent has no effect.

672 Beaver

“Some old trappers, when setting trapsunder the ice, cut four stakes, three of greenpoplar and the other of some kind of drywood. These are driven down through thehole in the ice close to the house, solidlyinto the bottom, forming a square about afoot each way. The trap is set and loweredcarefully to the bottom by means of twohooked sticks, the ring on the chain beingslipped over the dry stake. This is not asure plan at all. There is nothing to preventthe beaver from cutting off the poplars abovethe trap and carrying them away. In fact,if the beaver gets in the trap, he is simplyplaying in hard luck. The best way is toshove down a small, dry tree with three orfour branches sticking out, on which thetrap can be set, and place the bait above itin such a fashion that the beaver will haveto step on the trap to reach it. But, if thewater is shoal enough, the safest way is toplace your trap on the bottom. It is, ofcourse, all important that the beaver shoulddrown soon after he is caught; otherwiseyou are very apt to get nothing but a claw,especially if he is caught by the forefoot,which can be twisted off very easily.

“The cutting of a hole in the ice andother disturbances caused by setting thetrap, of course, scare the beavers in thehouse, and you are not likely to catch anyfor two or three nights. But, the beavers can-not escape, are very hungry for fresh food,and after they get over their panic will read-ily walk into the trap.

“The ability of a beaver to remain underwater for a long time is really not so harda problem as it looks. When the lake orpond is frozen over a beaver will come to

Ways

the under surface of the ice and expel hisbreath so that it forms a wide, flat bubble.The air coming in contact with the ice andwater is purified, and the beaver breathesit in again. This operation he can repeatseveral times. The otter and muskrat dothe same thing. When the ice is thin andclear I have often seen the muskrat attachedto his bubble, and by pounding on the icehave driven him away from it, whereuponhe drowns in a very short time.

“It almost takes a burglar-proof safe tohold a newly captured beaver. I oncecaught an old one and two kittens up thenorth branch of the Sou’west Miramichi,put them in a barrel, and brought themdown to Miramichi Lake. That night theold beaver gnawed a hole through thebarrel and escaped, leaving her kittensbehind. They were so young that I had noway of feeding them, so released them inthe hope that the mother might find them.Soon afterward I caught a very large malebeaver. I made a log pen for him of dryspruce, but the second night he cut a log outand disappeared. Beavers, when alarmed,generally make up stream, so I went up thebrook to where a little branch came in, andthought I would give that a look, and Ihadn’t gone more than ten rods before Icame across my old friend sitting up in thebed of the brook having a lunch on a stickhe had cut. He actually looked as if heknew he was playing truant when he caughtsight of me out of the side of his eye. Ipicked him up by the tail, brought himback, put him in the pen, supplied him withplenty of fresh poplar, and he never gaveme any more trouble.”