BCS - ClavichordBCS The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society Number 37, Winter, 2014 page 1...

Transcript of BCS - ClavichordBCS The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society Number 37, Winter, 2014 page 1...

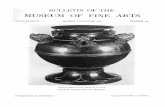

BCST h e B u l l e t i n o f t h e B o s t o n C l a v i c h o r d S o c i e t yN u m b e r 3 7 , W i n t e r , 2 0 1 4

page 1TANGENTS / The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society, Winter, 2014

(Continued on p.4)

I N S I D E T H I S I S S U E

(Continued on p.5)

TANGENTS

Peter Bavington: An Appreciation Peter Sykes

Clavichord for Beginners by Joan Benson, Indiana University Press, 2014

After a long and successful career as clavichord evangelist, Joan Benson

has captured her highly personal approach to teaching in her new book, Clavichord for Beginners. The book is a self-study guide, addressed to those having access to a clavichord but not to a teacher. The ideal reader brings a “beginner’s mind,” and a willingness to find short-term gratification in touch and sound rather than in music. A great strength of the book is the attention and detail given to physical matters: body and hand position, touch and movement. This material is carefully organized, and will surely reward patient application.

In the first chapter, Benson direct-ly addresses those who might consider the advantages of engagement with the clavichord in support of performance on other instruments, as well as those who approach the clavichord for its own sake. Three chapters of the book provide carefully conceived exercises in touch, dynamics, articulation, and ornaments. The reader must wait until more than halfway through the book before being al-lowed to play the first easy pieces, by Türk, J. W. Hässler, Christian Petzold, Mozart, and Francesco P. Ricci.

Useful excerpts from Türk’s Klavierschule, C.P.E. Bach’s Versuch, and many other pri-mary sources, are included to illustrate par-ticular points. An extensive list of references is provided for those wishing to explore the literature further.

The final chapters provide a look ahead to more advanced studies, with a condensed historical survey of the clavichord repertoire.

Clavichord for Beginners Review by Paul Rabin

Peter Bavington

Peter Bavington has contributed to to-day’s world of the clavichord in multiple

ways – as a builder of new instruments, a restorer of old instruments, a researcher on organological matters, a speaker, a writer, a player (self-taught!), and as a founder, for-mer chair, and contributor to the activities of the British Clavichord Society. He is the editor of the British Clavichord Society Newsletter, and a contributor to its pages, and the author of the book Clavichord Maintenance, which encompasses every-thing a clavichord owner needs to know about the structure and maintenance of the instrument.

Born in 1942, he began a career as a civil servant; in 1982 he changed direction, studying early keyboard instru-ments under Lewis Jones at the London College of Furniture, finishing in 1985 with a Higher National Diploma in Musical Instrument Technology with distinction in every unit. He founded his own workshop in London in 1987 to build new clavichords, harpsichords and fortepianos. Since 1998 he has focused primarily on clavichords; by his own admission, “[producing] a really responsive clavichord is the supreme chal-lenge for a keyboard instrument maker.”

In addition to building and restoring activities, he undertakes acoustic and historical research and is a regular par-ticipant in international organological conferences, presenting papers such as “The Clavichords of Haydn and C.P.E. Bach,” “Understanding the Clavichord,” “Some Aspects of Clavichord Design and Set-Up,” and “Clavichord Making in the 1890’s and Today.” He also offers drawings of two historic clavichords.

As a restorer of old instruments, he has worked on such diverse instruments as the Hoffman clavichord now at Hatchlands, and the Dolmetsch/Chickering #51 from 1910; a careful and complete report on the latter restoration was published in Clavichord International in November 2011 (Vol. 15, No. 2.)

As a builder, he has produced instru-

ments inspired by many different his-torical models, including full-sized and travel models and fretted and unfretted designs. His clavichords have been based on instruments of German, Spanish and Portuguese provenance, as well as on an instrument described by Marin Mersenne

in a 1636 treatise.He makes practically ev-

ery part of the instrument himself including the met-al work such as tangents, tuning pins, and hinges. Like many fine builders he is most concerned with the type, quality, and moisture content of the wood with which he works. Machines are only used for the preparation

of the wood stock; the joinery, including dovetailed case corners and the creation of moldings, is mostly done by hand. He uses hot animal glue, as did the builders of all sorts of musical instruments in the past.

Historic instruments are studied as refer-ence points. It is not enough for him simply to copy the dimensions of old instruments. It is important for him to understand the principles upon which they were construct-ed and the musical values that are served by their construction and design in order to apply his own skill and judgment to create new instruments as responsive and beautiful in sound as the old ones. For this reason, Bavington clavichords are not described by their builder as “copies” of old instruments. They are “based on” the originals, but at the same time are new creations. His player’s understanding of the instrument, his appre-ciation and observational insight regarding the historic and acoustic properties of the old instruments, and his care and skill as a creator of new instruments have resulted in new clavichords that are prized by their owners, whether individual or institutional.

(Continued on p.3)

C.P.E. Bach at Cornell . . . .p.2Instruction in Japan . . . . . .p.3J.H. Silbermann . . . . . . . . .p.7

T A N G E N T S

The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society, published by The Boston Clavichord Society, P.O. Box 540484, Waltham MA 02454.

ISSN 1558-9706 http://www.bostonclavichord.orgPaul Monsky, Webmaster

The Boston Clavichord Society is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the promotion of the clavichord and its music. For information on becoming a Friend of the Society, please write to the above address.

TANGENTS is published biannually in the spring and in the fall, and is sent free to Friends of the BCS. Single copies and back issues can be obtained by writing to the address below.

Editor: Beverly WoodwardP.O. Box 540484, Waltham MA 02454 Phone: 781, 891-0814

Submissions: This bulletin is a forum for its readers. We welcome articles, letters, questions and other contributions. Copy can be submitted by mail, e-mail or diskette to the Editor. Please contact her about preferred format before submission.

Board of Directors: Peter Sykes, President David Schulenberg, Vice PresidentBeverly Woodward, Coordinator & Treasurer Paul Monsky, Assistant Treasurer Paul Rabin, Clerk Tim Hamilton, Assistant ClerkSylvia BerryChrista Rakich Leon Schelhase

TANGENTS / The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society, Winter, 2014page 2

A C.P.E. Bach Tercentenary Conference at CornellDavid Schulenberg

David Schulenberg’s book The Music of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach was re-cently published by the University of Rochester Press.

Sensation & Sensibility at the Keyboard in the Late Eighteenth Century,

announced as a conference celebrating the tercentenary of the birth of C. P. E.Bach, took place Oct. 2–4, 2014, at Cornell Uni-versity in Ithaca, NY. Sponsored jointly by Cornell’s Department of Music, the Westfield Center for Historical Keyboard Studies, and the Atkinson Forum in Ameri-can Studies, the event brought together scholars and performers for three days of talks and concerts. Annette Richards, Cornell professor of music and university organist, was the chief organizer as well as organ soloist in Bach’s G-major concerto, Wq. 34, joined in the latter by Ars Lyrica Houston, directed by Matthew Dirst.

Among events of special interest to BCS members were two clavichord recitals, in-cluding one by Tom Beghin, playing similar repertory (and the same instrument) heard earlier this year at Harvard’s Houghton Library. Peter Sykes, president of the BCS, closed the conference with a performance of three of Bach’s most notable sonatas, alongside the A-minor Rondo and works by Beethoven and Haydn. The audience of perhaps 125 was deeply moved by Sykes’s magisterial performance, which included an affecting encore, the opening prelude

from Sebastian’s Well-Tempered Clavier. This recital took place in Cornell’s Anabel Taylor Chapel, where the conference had opened with a concert by David Yearsley on the great Yokota/GOArt organ after Arp Schnitger, in a program that included Bach’s fantasia and fugue, Wq. 119/6, as well as works by his father and brothers, many of them arranged by the performer.

Notable among the talks were several that addressed 18th-century notions of the relationships between music, instruments, and the body, including a keynote address by James Kennaway on “The Nerves, Refine-ment, and Over-Stimulation: Medicine and Music in the Age of Sensibility.” Matthew Head discussed Bach’s A-major fantasia, Wq. 58/7, Yonatan Bar-Yoshafat the so-called Program Trio, Wq. 161/1, and Richards the meaning of Empfindsamkeit (sensibility) in Bach’s later music. Of special interest was a demonstration by Dennis James of his reconstructed glass harmonica, an instrument of the late 18th and early 19th centuries whose technique and documented effects on players and listeners have some things in common with the clavichord. A second keynote address by Richard Kramer was concerned with settings of the poetry of Klopstock not only by Bach, but by Beethoven’s teacher, Christian Gottlob Neefe.

Other events included a fortepiano recit-al by Andrew Willis, student performances, and a clavichord masterclass led by Sykes. He prefaced the latter with informative remarks on the Dolmetsch/Chickering clavichords, one of which was brought to Ithaca and made available to the players. Ω

AnnouncementThe International Centre for Clavi-

chord Studies has announced the themes of the XII International Clavichord Symposium to be held in Magnano, Italy, September 1-5, 2015. The planning com-mittee is now accepting proposals for papers with a preference for topics on: The Clavichord as a Pedagogical Instru-ment, Past, Present, and Future. Other topics, such as history, restoration, and building are also welcome. Proposals for

Corrections1- The address of FIMTE, the Interna-

tional Festival of Spanish Keyboard Music, and of Luisa Morales has changed. The new address is: Luisa Morales, FIMTE, Calle Cer-vantes 37, 04630 Garrucha, Almeria, SPAIN.

2- In the last issue of Tangents, #36, the final four words of David Schulenberg’s re-view of Tom Beghin’s clavichord recital at Harvard were inadvertently dropped. The last sentence should have read:

Afterwards, this writer rushed home to try playing some of these same pieces with the same attention to timing and expression that prevailed throughout this inspiring concert. Ω

performances should include a program of thirty minutes of music. Proposals for the exhibition of instruments should include all pertinent information on the copy or original to be displayed. Propos-als should be addressed to the ICCS Committee no later than February 28, 2015: ICCS, Via Roma 43, 13887 Mag-nano (BI), Italy. Further information may become available at the ICCS website: http://www.MusicaAnticaMagnano.com

page 3TANGENTS / The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society, Winter, 2014

Clavichord Instruction in Japan

University-level programs1) Ferris University is the only school

in Japan that offers clavichord lessons to organ and piano students (actually students with any major) as a minor subject on a regular weekly basis. Organ students are required to study the clavichord. However, it is not possible to major in the clavichord. The lessons are taught by Tomoko Miya-moto. The instrument is an unfretted Hass model made by Keith Hill. The university is also renting a double-fretted instrument from Yasushi Takahashi.

2) The Early Music Department at the Tokyo University of the Arts gives a clavi-chord intensive workshop one or two days per year for piano, organ, and harpsichord

Naoya Otsuka is an Associate Professor in the Early Music Department, Tokyo University of the Arts

majors. It is not compulsory. There is no regular major or minor program for the clavichord. For students majoring in the harpsichord (Bach-elor level), clavi-chord performance is required in the July exam each year. It is com-prised of 1) scales according to C.P.E. Bach’s Versuch , 2) a C.P.E. Bach Probestück. As a re-sult of this require-ment, harpsichord students play four exams on the clavi-chord before they graduate. As prepara-tion they get clavichord lessons, which I teach. The clavichord is a five-octave unfretted instrument by Joel Speerstra after Friederci.

Other possibilities for clavichord lessons in Japan

1) Shirakawa Organ Academy is an an-

Naoya Otsuka

nual one-week organ academy in Shirakawa which includes clavichord lessons..

2) The Ongakuno-Kakurega workshop (one-a f te rnoon workshop) in To-kyo. This work-shop was started by Akihiko Yamanobe (clavichord build-er) and me in 2002 to provide a first experience with the clavichord for everybody. So far, more than 200 people have come

and touched the clavichord in this work-shop: piano or organ lovers from three- year-old children to the lady in her 70’s. Many piano teachers have also participated. Mr. Yamanobe teaches the structure of the instrument and how to tune, while I give lessons on playing the instrument. We use a 4½-octave unfretted clavichord, made by Akihiko Yamanobe after Hubert. Ω

The first meeting of the Michigan Clavichord Society was held on Sep-

tember 6, 2014, at the home of Carol lei Breckenridge, near Ann Arbor. Four instruments were on hand: Carol lei’s two excellent clavichords, an unfretted 5-oc-tave instrument built by Paul Irvin based on a 1767 Friederici and a double-fretted clavichord built by Herrick and Kottick based on a 1784 Hu-bert, as well as two of Gregory Crowell’s instruments, a triple-fretted by Michele Chiaramida after Praetorius’s Gemein Clavichord, similar to the 17th-century Flemish instrument in the Mirrey Collection in Edinburgh, and a Peter Bavington double-fretted, based on a ca.1700 anonymous German instrument in Leipzig.

Much of the time was spent discussing issues with clavichord construction and trying out the instruments. Music from the Deutschen Clavichord Societaet Collectio Operum Musicorum was played (an intrigu-

Michigan Clavichord Society in FormationCarol lei Breckenridge

ing collection of less known pieces from the personal libraries of Sally Fortino and Paul Simmonds, that anyone with an inter-est in the clavichord will want to obtain). In addition, Carol lei played a sonata by Domenico Scarlatti, K. 213, on the large

Irvin clavichord and Martha Folts played Pavane Lachrimae by Sweelinck on the “Hu-bert” and Bavington instruments. Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra (author of Bach and the Art of Improvisation) tried all the clavichords, as well

as other keyboards in the room (Nea-politan & French harpsichords from the Zuckermann shop, Dulcken fortepiano by Thomas and Barbara Wolf, Cristofori-Ferrini fortepiano by David Sutherland, and an Erard piano of 1876).

At the conclusion we agreed to meet next in the Grand Rapids area, in order to see and hear Gregory Crowell’s collection of clavichords. (Photographs and descriptions of these clavichords were published in issue #35, fall 2013, of Tangents. Ed.) Ω

The value of the book is considerably augmented by the accompanying DVD and CD. The DVD presents tutorials and recorded student lessons that usefully sup-plement the exercises on hand position a n d t o u c h , as well as a recent inter-view, and brief performances of C.P.E. Bach and G.C. Wa-genseil. The CD includes excerpts from Benson’s recorded perfor-mances of Froberger, C.P.E. and W.F. Bach, Mozart, and Haydn, on four different clavichords and a 1795 Broadwood piano, all from 1962-1982, plus a more recent performance of John Cage’s In a Landscape (1948) on a modern Hamburg Steinway.These all convincingly demonstrate the success of her approach for a variety of instruments and repertoires.

Benson’s book fills a real need; hope-fully it will find its way into the hands of students of all ages. Ω

(Benson Book, Continued from p. 1)

Unfretted clavichord after Hass by Keith Hill, 1977

TANGENTS / The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society, Winter, 2014page 4

1- Clavichord after J. H. Silbermann, original (attributed) in Nuremberg.

This is a compact five-octave unfretted instrument that Bavington describes as having “the liveliness and presence of a small fretted one.”

2 / 3 - Lima (“Early Spanish”) clavichord and rose.

This clavichord is based on a clavichord discovered in Peru in 1998 that was the subject of an article in De Clavicordio IV in 2001. Its design is that of a sixteenth-century instrument, with separate bridges without bridge pins, and a second sound-board (with a hidden rose) under the keylevers

4- Travel clavichordSmall travel clavichords were used by

both Haydn and Mozart. This instrument is based on a number of surviving instru-ments of the period. It speaks at A-440 pitch, is double-fretted and single-strung in the bass octave.

5- MersenneThis instrument is a reconstruction

of an instrument called “manicordion” described by Marin Mersenne in his Har-monie universelle of 1636. Many details were precisely indicated in the treatise, but many others were supplied by Bavington’s

insights into what makes a clavichord work well (for example in deciding upon an appropriate stringing schedule), and from observation of other contemporary building practices. The barrel-vaulted lid posed special challenges in woodworking, especially as regards the convexity of the inside. Bavington states that these sorts of lids, sometimes found in “square” early instruments, solve the problem of making a lid that is light, strong, and not disturbed by humidity changes.

6- “Bavdechtel”This instrument illustrates how a

builder’s observation of an original instrument’s design principles, supple-mented by his own experience, can lead to a new instrument suited to the needs of today. This instrument is based on a very late fretted clavichord built by Jo-hann Jacob Bodechtel of Nuremberg in 1785. Bavington added one note to the keyboard and altered the design some-what, thus the nickname “Bavdechtel” for this instrument.

7- PortugueseDouble-fretted clavichord based on an

anonymous eighteenth-century instrument of probable Portuguese origin. Bavington observed the restoration of the original and based the design on that experience.

8- Early 17thC GermanDouble-fretted clavichord in meantone

temperament based on published details of an instrument in the Leipzig museum (no. 10). In building it, Bavington dis-covered a number of proportional rela-tionships throughout the design of the instrument; for example, it is made in two symmetrical halves. This instrument has split sharps for D#/Eb; the picture was taken by the owner, Mads Damlund, in his church in Gentofte, Copenhagen. 9- Beauchamp

This instrument, made for a group that presented educational programs about me-dieval music in schools around Warwick-shire, is based on an instrument portrayed in a stained glass window in the Beau-champ Chapel of the Collegiate Church of St Mary, Warwick. There is evidence from that time (mid-fifteenth century) indicating that the images in the chapel’s windows were based on real instruments. Bavington also examined evidence about other early clavichords, including the MS of Arnault de Zwolle (c. 1460). The Beau-champ instrument has a compass of three octaves, G-g2, at four-foot pitch and ten courses of strings.

A Gallery of Bavington Clavichords

1

2

3

page 5TANGENTS / The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society, Winter, 2014

4 5

6

7

8 9

TANGENTS / The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society, Winter, 2014page 6

The conference of the German Clavi-chord Society in October in Bad Kro-

zingen this year was an eye opener for me. I am a sixty-nine year old piano tuner and harpsichord technician from Alaska who has been out of touch with the clavichord world for many years. In Boston in the early 1970s I built a couple of clavichords and subsequently acquired a couple more. Then I moved out West and finally to Alaska where I believe the only four clavichords in the state are in my house. So when I heard about the conference I jumped at the op-portunity to go to Europe and catch up. My instruments are from the days when we used zither pins, lead weights in the keys and white listing felt stuffed between the string pairs. I saw no such unhistorical practices in Bad Krozingen where I learned much I had not known about period instruments and the features that made them more useful and musical.

The conference was held in a small castle which houses the instrument collection of the late harpsichordist Fritz Neumeyer. The collection is remarkable in that all the instruments are kept in playing condition and all are gorgeous sounding. Conference attendees could not keep their hands off them. We went from instrument to instru-ment playing the scraps of music in our fingers while trying to hear over the din of everyone else playing. Memorable for me were a robust sounding fretted clavichord from 1787 by Spaeth and Schmahl, a John Koster harpsichord after Zell with a golden treble, a delicate 1801 tangent piano by Schmahl, and most of all, four big clavi-chords after Friederici with lots of bass and long sustain. Two were by Martin Kather (surprisingly different from each other) and one each by Thomas Steiner and Benedikt Claas. I wanted to steal them all and take them home to Alaska.

Lectures and concerts continued throughout the long weekend. Since I am not a German speaker the lectures were mostly lost on me. But Germans, it seems, all speak English and there was no shortage of friendly people to tell me what was said. Given the quiet nature of clavichords, it

A Clavichord Conference in GermanyDick Reichman

was surprising that the concerts could be heard so well. They were easily heard and enjoyed with as many as fifty people in the audience. Not only were the instruments often quite loud, but the acoustics of the performance hall were bright and clear, only occasionally blurred by the sound of distant church-bells in the town outside.

Two concerts were played by the wonder-ful Mathieu Dupouy. He brought poetry and power to the music of Emanuel Bach

and his contemporaries, reminding us of the easy-to-forget fact that they were avant-garde composers in their time. Read-ing from tablature, Michel Bignens played music of the 15th and 16th centuries, mu-sic that was new to me. His performance was intimate and touching. His instru-ment, after Pisaurensis by Sander Ruys, was very small. It had a discontinuous bridge (in three segments) and sounded glorious despite the fact it looked so primitive. I was later amazed to learn that it was fretted in such a way that it could be tuned entirely in octaves. Maria Bayley took us back to the Renaissance with a heartfelt concert on the same clavichord. She also played a pretty-sounding clavicytherium (an upright harpsichord). Enno Kastens gave a masterful performance on the tangent piano. The tangent piano sounds like a harpsichord but can play loud and soft. If only Landowska had known about it! Jermaine Sprosse played C.P.E. and W.F. Bach with Lisztian velocity. It was excit-ing but unclear. He played faster than his clavichord could speak the notes.

Special thanks to the builder Martin Kather who took time to answer my many questions about tuning, voicing, damping, key-weighting, and the general mainte-

nance of clavichords. When I returned to Alaska I made a number of improvements to my own clavichords based on tips he gave me. He brought his young son with him to the conference and told me he was training the boy to be an instru-ment builder too. But first he would teach him to cook, an art which he regarded as fundamentally similar. Thanks also to Freiburg harpsichordist Julia Theis who befriended us and translated much of the

goings on. When the conference was over she took us on an auto tour of the hauntingly beautiful nearby Black Forest. And thanks to Swiss clavichordist Paul Simmonds, one of whose recordings I had known for years. He lent his knowledge and enthusiasm to everyone at the event. I bought more of his recordings, all wonderfully played unusual music on beautiful clavichords.

The German Clavichord Society, or the DCS, holds these events on a regular basis. Their president, Thom-as Bregenzer in Berlin, made us feel

most welcome and is the man to contact if you want information about future meet-ings [[email protected]]. I hope to go again someday (after learning a little German) and spend more time with these lovely people who share my enthusiasm for old keyboard instruments. Ω

Castle housing the Fritz Neumeyer collection, Bad Krozingen

Peter Bavington on making a curved lid:

A series of ‘staves’ have to be joined accurately edge-to-edge, but with a

slight angle to the edges so that they end up as a series of flats forming an approximation to the required curve. The joints must be perfect, but you can’t easily use cramps to bring the two edges together, as you can when they are straight-on. Having produced this series of flats, you now have to shape them into a gentle smooth curve, equal all the way along: not so hard to do on the outside, but getting the inside regular and smooth is a challenge if, like me, you have not invested in special barrel-maker’s planes for the purpose!

page 7TANGENTS / The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society, Winter, 2014

On his website, Peter Bavington speaks of “five unsigned eighteenth-century unfret-ted clavichords” that have survived and are similar in design. The instruments have been attributed to Johann Heinrich Silbermann, but Bavington and others have questioned the attribution. As a result of the questions raised about their attribution, the German builder Di-etrich Hein was asked to undertake a thorough examination of the instruments. One of them, the one in Vienna, was recently ruled out as possibly by JHS. (Details will be provided in a forthcoming article.) Below, Hein reports on his investigation of three of the other four instruments. [Editor]

Among the many unsigned historical clavichords still in existence, is a group

of four very similar instruments of the large unfretted type with a compass of FF - f‘‘‘. I am engaged in a project that involves taking a closer look at each of these four instruments and comparing constructional details with the spinets and a fortepiano of Johann Heinrich Silbermann (Strasbourg 1727-1799). These instruments are of

Observations on three clavichords attributed to Johann Heinrich Silbermann: A Builder’s PerspectiveDietrich Hein

particular interest, not only because they are extremely well designed and show an extraordinary level of craftsmanship, but also because of a possible connection to the work of Gottfried Silbermann, Johann Heinrich’s uncle in Saxony.

Curt Sachs, founder of modern organol-ogy and the former (1919-33) director of the collection of musical instruments in Berlin (Staatliche Musikinstrumentensam-mlung), attributed two clavichords in this group (which are part of the Berlin col-lection) to Johann Heinrich Silbermann, based on similarities with a fortepiano in the Berlin collection that bears his signature and the place and year on the nameboard above the keys.

The remaining two members of the group described are now in the collections of Nürnberg (Germanisches Nationalmuseum) and Paris (Musée de la Musique). While the Paris instrument is yet to be looked at in this context, the other three have been thoroughly examined by me recently. These examinations show that the three clavichords are undoubtedly from the same

The 3 photos immediately below, of the Ber-lin 914, Berlin 598 and Nürnberg clavichords respectively, look inside the instruments (to-wards the treble end of the keyboard) with their keys out, showing the backrail with the guiding-slots (or guiding-rack) and also show-ing the bellyrail with the characteristic holes and the endgrain of the soundboard.

workshop, and comparisons with a spinet by Johann Heinrich Silbermann (1767) in the Nürnberg collection, another similar spinet by the same maker from about 1765 in the Bachhaus/Eisenach, as well as the fortepiano in Berlin, reveal a number of common features that lead to the conclu-sion that all of these instruments are the work of Johann Heinrich Silbermann. Besides a recognizable “language” in Sil-bermann’s woodwork, including the choice of woods and joinery, it is particularly the execution of the keyboards, which exhibits many common characteristics, that proves the common origin.

Once this project is completed, more photos and detailed descriptions will be part of a forthcoming article. Ω

Far left: Hitchpins in the bass of the clavichord by JHS (Berlin 598) showing typical hitchpin rail and key-guiding-rack.

Left: Detail of the keys of the clavichord by JHS in Nürn-berg, showing the carving, balance points and typical thick bone on the sharp key.

TANGENTS / The Bulletin of the Boston Clavichord Society, Winter, 2014page 8

The Boston Clavichord Society P.O. Box 540484Waltham MA 02454

www.bostonclavichord.org