Bach-Busoni Jan Michiels · 2019. 12. 12. · Bach-Busoni Jan Michiels . MENU Fug a U 760 5 Ba J M...

Transcript of Bach-Busoni Jan Michiels · 2019. 12. 12. · Bach-Busoni Jan Michiels . MENU Fug a U 760 5 Ba J M...

-

Bach-Busoni

Jan Michiels

CLASSICAL

-

MENU

FUG 760

2

EN FR DE

Credits Tracklist Programme note

Bach-Busoni

Jan Michiels

-

MENU

3

Fuga Libera

Artistic Director

Jérôme Lejeune

Design

Stoëmp Studio

Editorial Coordinator

Julien Lepièce

Photography

Jan Michiels booklet: © Jochen Schollaert,

digipak: © Michael Seum

piano: © Studio Claerhout, Ghent

Cover

Max Oppenheimer (1885–1954),

Portrait of Ferruccio Busoni (1916)

Berlin, SMB, Nationalgalerie.

© akg-images / Erich Lessing

Recording

Maene concerthall (Ruiselede), 9, 10 June 2019

Recording & Mastering

www.acousticrecordingservice.be

Yannick Willox

Piano tuner

Peter Head

Deutsche Übersetzungen

Susanne Lowien

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

4

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

Jan Michiels, piano Bechstein 1860 (collection Chris Maene)

& Maene Straight Strung Grand Piano 2015

www.michielsjan.be

Bach-Busoni

Jan Michiels

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

5

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) / Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924)

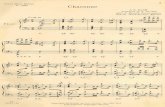

01 . Chaconne aus der Partita BWV 1004 (1893/1916) 13’41

Zehn Choralvorspiele (1898/1916)

02 . Komm, Gott Schöpfer, heiliger Geist BWV 667 2’1103 . Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme BWV 140 3’1704 . Nun komm’ der Heiden Heiland BWV 659 4’2005 . Nun freut euch, Lieben Christen g'mein BWV 734a 2’1706 . Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 639 3’1307 . Herr Gott, nun schleuss den Himmel auf BWV 617 2’0308 . Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt BWV 637 1’4709 . Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt BWV 705 3’4110 . In dir ist Freude BWV 615 2’4511 . Jesus Christus, unser Heiland BWV 665 5’24

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

6

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

Ferruccio Busoni

12 . Fantasia Contrappuntistica (1910) 32’22I . Preludio Corale II . Fuga I III . Fuga IIIV . Fuga IIIV . IntermezzoVI . Variation IVII . Variation IIVIII . Variation IIIIX . CadenzaX . Fuga IVXI . CoraleXII . Stretto

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

7

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

ENIt is not so easy to find Ferruccio Busoni’s equal in music history: he was a world-famous phenomenal pianist, a highly influential pedagogue, a conductor of new orchestral works, a theoretician of genius, an extremely cultivated and erudite man, a citizen of the world, a child of his own disintegrating time, a prophet of the ‘music of the future’, freed from the fetters of authority (in his Sketch for a New Aesthetic of Music Busoni foretells the twelve-tone and the six-tone systems and even electronic music) and of course he was also a composer – one who is still awaiting a proper evaluation worthy of his genius.

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

8

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

A cathedral with chorales for Johann Sebastian Bach

Bach’s music was the fundamental root of piano playing for Busoni, who had his own cyclical view of music history: Liszt was the summit and the study of Bach and Liszt made Beethoven possible. Busoni explained his fascination for Bach and his music in the introduction to his 1894 edition of Das Wohltemperierte Klavier:

“Johann Sebastian Bach contributed huge blocks to the foundations of the edifice of Music, laying them firmly and unshakably one upon the other […]. His thoughts and feelings were generations ahead of his time; the means then available to him for their realisation were simply inadequate. This alone can explain the fact that a broader arrangement together with the modernisation of certain of his works does not seem to violate the accepted Bach style, but seems rather to bring it to full perfection.”

Busoni wrote euphorically to his publisher at the end of May 1897:

“Here are the chorale preludes for organ by the great Sebastian […] which I have prepared with love and great care. The selection is a for-tunate one; the volume is a veritable jewel box that contains the most exquisite craftmanship. I hope that this work will find wide circulation, for I hardly know of any piano music better than this.”

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

9

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

He wrote in his introduction to the edition of ten selected Chorale Preludes (1898):

“This type of arrangement, which we describe as in the style of chamber music as opposed to concert arrangements, rarely requires the player’s utmost technical skills, although he must have complete command of the art of touch on the pianoforte in order to perform these Chorale Preludes.”

An organist employs different stops and manuals to colour the different voices, while the pianist needs to adapt different graduations of touch within one basic colour. Busoni integrated the pedals of the organ with octave displacements and arpeggiation, whilst the chorale melodies are sometimes played in octaves and are heard in different articulations such as tenuto, slurs, staccato and more. Busoni goes slightly beyond the original text on a few occasions by adding tempo mark-ings, dynamics and even by adding notes and new voices; he even at times adds some measures of his own at final cadences. He published the final edition of this volume in 1916, complete with a new version of the first prelude; this is included on this recording. That same year he edited the final version of a transcription of one of Bach’s supreme masterpieces: the Chaconne for solo violin from the Second Partita. Prof. Helga Thoene (Düsseldorf) provided convincing proof some decades ago that this Chaconne is in fact an epitaph in music for Bach’s first wife Maria Barbara. Not only did Bach inscribe her name cryptographically in the opening bars, but he also used numerous chorales, including Christ lag in Todesbanden, as a backbone for the structure of the whole.

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

10

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

Busoni’s transcriptions of Bach met with much opposition. His defence is worth reading:

“Every notation is itself the transcription of an abstract idea. The instant the pen seizes it, the idea loses its original form […]. A performance of a work is also a transcription and, no matter whatever liberties it may take, it can never annihilate the original. The musical artwork exists, complete and intact, before its tones begin to resound and after they have died away. It exists both within and outside of Time.”

Busoni had — as a good Italian — a consummate feeling for form; he hated anything chaotic, although a nostalgia for freely floating music is often to be felt in many of his compositions. This paradoxical conflict leads us directly to the Fantasia Contrappuntistica. Busoni met Bernhard Ziehn and Wilhelm Middelschulte, two experts in the theory of counterpoint, during a tour of the USA in 1910; he later nicknamed them ‘The Gothics of Chicago’:

“While bricks of stone were erected to build multi-storey-houses around them […] while these ugly symbols of superficial thinking kept growing faster and closer to similar heights […] two men were sitting in serious silence in the same Chicago and cultivated — looking inwards — the art in which the joy of ornament, the possibility of power, feeling, fantasy, severe calculation and mystical belief all coexisted: the Gothic Art […]. Everything is ingeniously ordered and cleanly structured even in the richest complexity — every detail is essential to the whole.”

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

11

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

Ziehn had discovered that Bach’s unfinished (triple) fugue from the Kunst der Fuge was actually conceived as a quadruple fugue, and that the missing fourth subject was the principal theme of the first fugue of the work. In that same year of 1910, Busoni composed his Grosse Fuge – Kontrapunktische Fantasie über Bachs letztes unvollendetes Werk für Klavier; a new version, however, followed immediately: Fantasia Contrappuntistica – Preludio al Corale Gloria al Signore nei Cieli e fuga a quatro soggetti obbligati sopra un frammento di Bach. Editione definitiva. Giugno 1910. The structure of this work is based on the architectural proportions of the Palace of the Popes in Avignon and comprises twelve sections: Preludio Corale / Fuga I / Fuga II / Fuga III / Intermezzo / Variation I / Variation II / Variation III / Cadenza / Fuga IV / Corale / Stretto. We might, perhaps, imagine this monumental piece as a cathedral in which dif-ferent styles coexist in peace. Two different instruments are featured on this recording. The chorale preludes are played on an original straight strung Bechstein from 1860; the other pieces, given that they depart more from the original Bach than the chorale preludes, are presented on a brand new modern piano from 2018: the Maene Straight Strung Chamber Music Concert Grand 250, a ‘new’ instrument with the ‘old’ Bechstein as its direct inspiration. Busoni’s views on music history were very similar:

“There is no Old or New. There is only Known or Unknown.” “Music is a part of […] the vibrating Universe.” “Music is like a divine child, not touching the earth with his feet, floating in the air.”

Jan Michiels

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

12

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

FRIl n’est pas facile de trouver l’égal de Ferruccio Busoni dans l’histoire de la musique : pianiste phénoménal de renommée mondiale, pédagogue d’une grande influence, chef d’orchestre n’ayant pas peur de diriger des œuvres contemporaines, théoricien de génie, homme de lettres extrêmement cultivé, homme du monde, enfant d’un temps en pleine désagrégation, prophète d’une « musique du futur » libérée du joug des autorités (dans son Esquisse pour une nouvelle esthétique de la musique, il prédit la dodécaphonie, le système à tiers de ton et même la musique électronique) et finalement compositeur… attendant toujours d’être apprécié à sa juste valeur.

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

13

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

Une cathédrale de chorals pour Jean-Sébastien Bach

La musique de Bach formait pour Busoni le fondement du jeu pianistique (et la musique de Liszt le sommet – l’étude de Bach et de Liszt rendit Beethoven pos-sible, telle était sa vision personnelle cyclique de l’histoire de la musique). Dans son introduction à son édition (1894) de Das Wohltemperierte Klavier, il explique sa fascination pour le cantor de la Thomaskirche :

« Johann Sebastian Bach a ajouté aux fondements de l’édifice de la musique d’énormes blocs empilés les uns sur les autres d’une façon ferme et inébranlable […]. Ses pensées et émotions étaient très en avance sur son temps ; les moyens d’expression à sa disposition étaient alors insuffisants. Ce fait seul peut expliquer pourquoi l’élargissement, la “modernisation” de certaines de ses œuvres ne violent pas le “style Bach” – au contraire, ils semblent le mener à la perfection. »

Fin mai 1897, Busoni écrivit en des termes euphoriques à son éditeur :

« Vous trouverez ici les préludes de choral du grand Sebastian [...] que j’ai adaptés avec beaucoup d’amour et avec le plus grand soin. Le choix opéré est heureux, si bien que ce recueil constitue un véritable trésor d’excellente facture. J’espère que cette œuvre sera largement diffusée : je serais bien en peine de trouver meilleure musique pour piano que celle-là. »

Dans son introduction à l’édition de ses transcriptions de dix Préludes de choral pour orgue (1898), Busoni écrivit encore :

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

14

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

« Ce type d’arrangement, que nous décrivons comme étant dans le style de la musique de chambre en opposition aux arrangements de concert, n’exige que rarement les plus hautes aptitudes techniques du musicien, bien qu’il faille maîtriser parfaitement l’art du toucher au pianoforte pour pouvoir exécuter ces Préludes de choral. »

Un organiste utilise en effet différents jeux ou claviers pour colorer les voix, tandis que le pianiste doit adopter un toucher varié dans le timbre « monochrome » du piano. L’intégration de la basse (jouée sur le pédalier de l’orgue) par Busoni se fait par l’utilisation d’octaves et d’arpèges, tandis que la mélodie est parfois jouée en octaves et avec diverses articulations (tenuto, legato, staccato, etc.). Souvent, Busoni transgresse légèrement le texte original par l’ajout d’indications de tempo et de dynamique, et même de certaines notes et de nouvelles voix. Dans certaines cadences, il ajoute même des mesures entières. Busoni publia la version définitive de ce volume en 1916, avec une nouvelle version du premier prélude (enregistré ici). Il publia la même année la version finale de la transcription de l’un des plus grands chefs-d’œuvre de Bach : la Chaconne tirée de la Deuxième Partita pour violon seul.

Il y a quelques décennies, Helga Thoene (Düsseldorf) a prouvé d’une façon très convaincante que cette Chaconne est en réalité une « épitaphe musicale » pour la première femme de Bach, Maria Barbara. Son nom est caché d’une manière cryptographique dans les premières mesures, et Bach utilise des chorals (comme Christ lag in Todesbanden) comme structure de base.

Ces transcriptions d’œuvres de Bach par Busoni se heurtèrent à de nombreuses critiques. Busoni se défendit avec ces mots :

« Toute notation est déjà la transcription d’une idée abstraite. Dès

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

15

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

l’instant où la plume s’en empare, l’idée perd sa figure d’origine [...] l’interprétation d’une œuvre est aussi une transcription qui, si librement qu’elle soit traitée, ne peut détruire l’original. Car l’œuvre d’art musicale existe avant d’avoir retenti et après qu’elle a fini de sonner, elle est là, entière et intacte. Elle est à la fois dans le temps et hors du temps. »

Busoni possédait – comme tout bon Italien – un sens de la forme très élaboré et il haïssait tout ce qui était chaotique ; nous trouvons pourtant dans plusieurs de ses pages une nostalgie pour la musique librement fluctuante. Ce paradoxe nous mène à la Fantasia Contrappuntistica… Lors d’une tournée en Amérique en 1910, Busoni rencontra deux théoriciens du contrepoint, Bernhard Ziehn et Wilhelm Middelschulte, qu’il surnommerait plus tard « les gothiques de Chicago » :

« Pendant qu’on bâtissait autour d’eux des édifices de plus de vingt étages en briques [...] pendant que ces laids symboles de la pensée superficielle continuaient à monter plus vite et à se rapprocher plus près [...] dans le même Chicago, deux hommes se concentraient en silence et cultivaient, en regardant vers intérieur, l’art de la joie de l’ornement, la possibilité du pouvoir, l’émotion, la fantaisie, le calcul sévère, la foi mystique : l’art gothique [...]. Tout est ingénieusement ordonné et pure-ment structuré, même dans la plus riche complexité. Chaque détail est indispensable à l’ensemble. »

Ziehn avait découvert que la (triple) fugue inachevée de Die Kunst der Fuge avait en réalité été conçue comme quadruple fugue, le thème principal du cycle étant utilisé comme quatrième thème. En 1910 toujours, Busoni composa sa Grosse Fuge – Kontrapunktische Fantasie über Bachs letztes

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

16

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

unvollendetes Werk für Klavier ; une autre version suivit immédiatement : Fantasia Contrappuntistica – Preludio al Corale ‘Gloria al Signore nei Cieli’ e fuga a quattro soggetti obbligati sopra un frammento di Bach. Editione defi-nitiva. Giugno 1910. La structure de cette œuvre monumentale s’inspire des proportions architecturales du Palais des papes en Avignon et se compose de douze sections : Preludio Corale / Fuga I / Fuga II / Fuga III / Intermezzo / Variation I / Variation II / Variation III / Cadenza / Fuga IV / Corale / Stretto. On pourrait peut-être imaginer cette Fantaisie monumentale comme une cathédrale dans laquelle coexistent plusieurs styles différents. Dans cet enregistrement, vous entendrez deux instruments. Les Préludes sont joués sur un Bechstein à cordes parallèles de 1860, tandis que les autres pièces (qui s’éloignent un peu (ou beaucoup) plus de l’original) sont jouées sur un piano de 2018, le Maene Straight Strung Chamber Music Concert Grand 250. Un instrument « nouveau » qui s’inspire directement de l’instrument « ancien »… Car c’est aussi une belle métaphore de la vision de Busoni de l’histoire de la musique :

« Il n’y a pas d’ancien et de nouveau. Il n’y a que le connu et l’in-connu. » Ou encore : « La musique est une partie […] de l’univers vibrant », ou finalement : « La musique est comme un enfant divin, qui ne touche pas la terre avec ses pieds – il plane. »

Jan Michiels

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

17

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

DEEs ist nicht ohne weiteres möglich, in der Musikgeschichte jemanden zu finden, der Ferruccio Busoni gleichkommt: Er war ein weltberühmter, phänomenaler Pianist, ein sehr einflussreicher Pädagoge, ein Dirigent neuer Orchesterwerke, er beschäftigte sich theoretisch mit dem Geniebegriff und war ein äußerst kultivierter und gebildeter Mensch, ein Weltbürger, ein Kind seiner eigenen, sich zersetzenden Zeit, ein Prophet der „Zukunftsmusik“, frei von autoritären Fesseln (in seinem Entwurf einer neuen Ästhetik der Tonkunst sagt Busoni die Zwölftonmusik und Sechsteltonsysteme und sogar die elektronische Musik voraus), und natürlich war er auch Komponist – und zwar einer, der noch auf die seinem Genie angemessene Würdigung wartet.

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

18

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

Eine Kathedrale mit Chorälen für Johann Sebastian Bach

Bachs Musik war für Busoni, der seine eigene zyklische Sicht auf die Musikgeschichte hatte, die fundamentale Basis des Klavierspiels: Liszt war der Gipfel, und die Beschäftigung mit Bach und Liszt ermöglichte Beethoven. Busoni erläuterte in der Einleitung zu seiner Ausgabe des Wohltemperierten Klaviers aus dem Jahr 1894, warum Bach und seine Musik ihn so faszinierten:

„Zum Gebäude der Tonkunst wälzte Johann Sebastian Bach Riesenquadern herbei und fügte sie, unerschütterlich fest, zu einem Fundament zusammen. […] Seiner Zeit um Generationen vorausgeeilt, fühlte und dachte er in solchen Größenverhältnissen, dass die damaligen Ausdrucksmittel diesen nicht genügten. Dieses allein erklärt, dass die Erweiterung, die ‚Modernisierung‘ einiger seiner Werke nicht gegen den ‚Bachschen Stil‘ verstößt, – ja, diesen erst zu vervollständigen scheint.“

Busoni schrieb Ende Mai 1897 euphorisch an seinen Verleger:

„Hier folgen die […] von mir mit Liebe u. großer Sorgfalt vorbereiteten Choralvorspiele des großen Sebastian. Die getroffene Auswahl ist glücklich, so dass das Heft ein wahres Schmuckkästlein köstlichster Kunstarbeit ist. Ich erhoffe mir von diesem Werke eine Verbreitung: wüsste ich doch […] kaum bessere Claviermusik anzutreffen, als diese.“

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

19

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

In seinem Vorwort zu seiner Ausgabe mit zehn ausgewählten Choralvorspielen schrieb er (1898):

„Die Art der Übertragung, welche wir im Gegensatz zu den ‚Konzertbearbeitungen‘ als eine solche ‚im Kammerstyl‘ bezeichneten, stellt an die technische Fähigkeit des Spielers nur selten die höchsten Anforderungen, will man zu diesen nicht die Kunst des Anschlages zählen, welcher es bei dem Vortrage dieser Choralvorspiele allerdings im umfassendsten Maaße bedarf.“

Ein Organist verwendet verschiedene Register und Manuale, um den Stimmen unterschiedliche Klangfarben zu geben, während der Pianist verschiedene Anschlagsintensitäten innerhalb einer Grundfarbe zur Anpassung verwenden muss. Busoni integrierte das Orgelpedal durch Oktavierungen und Arpeggien, während die Choralmelodien manchmal in Oktaven gespielt werden und in ver-schiedenen Artikulationen wie tenuto, mit Bindungen, staccato und anderen zu hören sind. Busoni erweitert den Originaltext mehrmals leicht, indem er Tempoangaben, Dynamik und sogar Töne und neue Stimmen hinzufügt; manchmal ergänzt er sogar einige eigene Takte in den Schlusskadenzen. Er veröffentlichte die letzte Ausgabe dieses Bandes 1916, einschließlich einer Neufassung des ersten Präludiums, die auf dieser Aufnahme zu hören ist. Im selben Jahr gab er die endgültige Fassung seiner Transkription eines der bedeutendsten Meisterwerke Bachs heraus: die Chaconne für Violine solo aus der Zweiten Partita.

Dass diese Chaconne tatsächlich ein musikalisches Epitaph für Bachs erste Frau Maria Barbara ist, hat Prof. Helga Thoene (Düsseldorf) vor einigen

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

20

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

Jahrzehnten auf überzeugende Weise nachgewiesen. Bach schrieb ihren Namen nicht nur kryptographisch in die Eröffnungstakte ein, sondern benutzte auch zahlreiche Choräle, darunter Christ lag in Todesbanden, als Rückgrat für den Aufbau des gesamten Satzes.

Busonis Bach-Transkriptionen stießen auf heftigen Widerspruch. Seine Verteidigung ist lesenswert:

„Jede Notation ist schon Transkription eines abstrakten Einfalls. Mit dem Augenblick, da die Feder sich seiner bemächtigt, verliert der Gedanke seine Originalgestalt […] Auch der Vortrag eines Werkes ist eine Transkription, und auch dieser kann – er mag noch so frei sich geberden – niemals das Original aus der Welt schaffen. Denn das musikalische Kunstwerk besteht vor seinem Ertönen und nachdem es vorüberge-klungen, ganz und unversehrt da. Es ist zugleich in und ausser der Zeit.“

Busoni hatte – als guter Italiener – einen ausgeprägten Sinn für die Form; er hasste alles Chaotische, obwohl in vielen seiner Kompositionen eine Sehnsucht nach frei schwebender Musik zu spüren ist. Dieser paradoxe Konflikt führt uns direkt zur Fantasia Contrappuntistica. Busoni traf Bernhard Ziehn und Wilhelm Middelschulte, zwei Spezialisten für Kontrapunkttheorie, 1910 auf einer Tournee durch die USA; später nannte er sie „die Gotiker von Chicago“:

„Während um sie herum steinerne Würfel von über 20 Stockwerken errichtet werden […], während diese schmucklosen Symbole eines

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

21

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

ausgleichenden Gedankens immer rascher und dichter in solche Höhen treiben […], in demselben Chicago sitzen in ernster Stille zwei Männer und pflegen – den Blick nach innen gerichtet – jene Kunst, in der sich die Freude am Zierlichen mit der Möglichkeit zum Mächtigen, das Gefühl mit der Fantasie, die strenge Berechnung mit dem mystischen Glauben zusammenfinden : die Kunst der Gotik. […] Alles ist sinnreich geordnet und in reichsten Gewirre rein gegliedert […] alles Einzelne zum Ganzen nötig.”

Ziehn hatte entdeckt, dass Bachs unvollendete (Tripel-)Fuge aus der Kunst der Fuge tatsächlich als Quadrupel-Fuge konzipiert war und dass das fehlende vierte Thema das Hauptthema der ersten Fuge des Werkes ist. Im selben Jahr 1910 komponierte Busoni seine Grosse Fuge – Kontrapunktische Fantasie über Bachs letztes unvollendetes Werk für Klavier; eine neue Fassung folgte jedoch unmittelbar darauf: Fantasia Contrappuntistica – Preludio al Corale Gloria al Signore nei Cieli e fuga a quatro soggetti obbligati sopra un frammento di Bach. Editione definitiva. Giugno 1910. Der Aufbau dieses Werkes orientiert sich an den architektonischen Proportionen des Papstpalastes in Avignon und gliedert sich in zwölf Abschnitte: Preludio Corale / Fuga I / Fuga II / Fuga III / Intermezzo / Variation I / Variation II / Variation III / Cadenza / Fuga IV / Corale / Stretto.

Man kann sich dieses monumentale Werk möglicherweise als Kathedrale vor-stellen, in der verschiedene Stile in Frieden nebeneinander existieren.

Auf dieser Aufnahme sind zwei verschiedene Instrumente zu hören. Die Choralvorspiele werden auf einem originalen Bechstein von 1860 mit parallel

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

22

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

gespannten Saiten gespielt; die übrigen Stücke, die mehr von der originalen Bach-Fassung abweichen als die Choralvorspiele, werden auf einem brandneuen modernen Flügel von 2018 präsentiert: dem Maene Straight Strung Chamber Music Concert Grand 250, einem „neuen“ Instrument, dessen unmittelbare Inspiration der „alte“ Bechstein war.

Busonis Ansichten zur Musikgeschichte gehen in eine sehr ähnliche Richtung:

„Es gibt kein Altes und Neues, nur Bekanntes und Unbekanntes.” „Musik ist […] ein Teil des schwingenden Weltalls “ „Musik ist wie ein schwe-bendes göttliches Kind das die Erde nicht mit dem Füssen berühret”.

Jan Michiels

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

23

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

The Chris Maene Straight Strung Concert Grand Piano

In the late 19th century, Steinway & Sons successfully brought to fruition the concept of the modern cross-strung grand piano. Ever since then, this construction concept has been imitated by all piano builders. It has resulted in a standardization of piano building and a uniformity of piano sound. As a reaction to this, the second half of the 20th century witnessed an intense quest for performance practices using historical instruments that bring back the greater sound diversity and transparency of older times.

As part of this movement, Chris Maene Factory soon began specializing in building harpsichords and pianofortes, based on Chris Maene’s renowned and unique collection of more than 300 historical instruments. This gradually led to the desire to build his own grand piano with different sonorous properties, aiming to offer a valid artistic alternative to existing concert grands. To accomplish this, Chris Maene went back to the original basic principle of straight,

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

24

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

parallel stringing, where the bass strings are not crossed over the other strings but run parallel to them.

In 2013 Daniel Barenboim commissioned Chris Maene to build “the perfect parallel-strung concert piano”. He wanted to reconcile the unique characteristic sonorous richness of the historical piano with the volume, clarity, power and playing comfort of the best modern concert pianos. Chris Maene had already been thinking of this new concept for a while, and with this project he could finally make his ultimate dream come true: building a concert piano that would bring together tradition and innovation.

In May 2015 Daniel Barenboim inaugurated his new straight strung grand piano with Schubert recitals in Vienna, Paris and London. The sound of the unique instrument was very well received by press, audiences and musicians alike. By now the Chris Maene Straight Strung Grand Piano is played all over the world by the best international concert pianists, and the Chris Maene Factory is building a full range of straight-strung grand pianos. The Chris Maene Straight Strung Concert Grand Piano is regularly used for concerts and recordings by artists such as Martha Argerich, Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Emanuel Ax, Eric Le Sage, Hannes Minnaar, Liebrecht Vanbeckevoort, Jan Michiels, Julien Libeer, Jef Neve and Bram De Looze.

For more information, please visit www.chrismaene.com

-

Fuga Libera FUG 760

25

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

-

Fuga Libera FUG 760

26

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

For even more great music visit

www.outhere-music.com/en/labels/fugalibera

-

MENU

Fuga Libera FUG 760

27

Bach-Busoni • Jan Michiels

![Bach - Piano Concerto in D Minor BWV 1052 (Busoni) [2 Pianos]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/547ff1c8b379595e2b8b5985/bach-piano-concerto-in-d-minor-bwv-1052-busoni-2-pianos.jpg)