B SMEs in international trade: stylized facts · 2016-09-27 · SMEs in international trade:...

Transcript of B SMEs in international trade: stylized facts · 2016-09-27 · SMEs in international trade:...

SMEs in international trade: stylized factsEvery firm that contemplates expanding its operations in a foreign country has to choose a specific market entry strategy. As trade is the most common form of internationalization for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), this section surveys available statistical evidence on the participation of SMEs in international trade in both developed and developing economies, and how their activities relate to traditional trade flows and to trade in the context of global value chains. The objective is to provide an accurate and detailed description of the SME trade landscape, but also to identify important gaps in information and data coverage.

B

Contents1. SME involvement in direct trade 31

2. SME involvement in indirect trade and global value chains 39

3. SME participation in international e-commerce 46

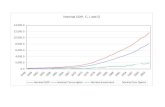

4. MSME trade participation over time 51

5. Conclusions 54

Some key facts and findings

•• Trade•participation•of•SMEs•in•developing•countries•is•low,•with•exports•accounting•for•7.6•per•cent•of•manufacturing•sales,•compared•to••14.1•per•cent•for•larger•firms.

•• MSMEs•account•for•34•per•cent•of•exports•on•average•in•developed•countries.•There•is•a•positive•relationship•between•enterprise•size•and•export•participation,•with•lower•rates•of•participation•for•micro•enterprises••(9•per•cent)•and•small•enterprises•(38•per•cent)•than•for•medium-sized••(59•per•cent)•and•large•enterprises•(66•per•cent).

•• In•developing•economies,•indirect•exports•in•the•manufacturing•sector•of•SMEs•were•estimated,•on•average,•at•2.4•per•cent•of•total•sales,•a•level••three•times•lower•than•the•estimated•share•of•direct•exports.•Most•manufacturing•SMEs•in•developing•countries•have•low•levels•of•integration••in•global•value•chains,•with•few•backward•and•forward•linkages•in•production.

•• In•developed•economies,•the•direct•contribution•of•SMEs•to•domestic•value-added•exports•is•predominant•over•indirect•exports.

•• Electronic•commerce•expands•opportunities•for•SMEs•to•participate•in•international•trade.•On•average,•97•per•cent•of•internet-enabled•small•businesses•export.•Meanwhile•export•participation•rates•for•traditional••SMEs•range•between•2•per•cent•and•28•per•cent•in•most•countries.

•• In•developing•countries,•there•is•an•inverse•relationship•between•the•number•of•employees•that•a•firm•has•when•it•begins•operations•and•the•number•of•years•before•it•starts•to•export.•For•large•firms•that•started•as•SMEs,•it•took•17•years•to•export•for•those•that•began•with•five•employees•or•less,•compared•to•five•years•for•those•that•had•60-100•employees.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

30

Internationalization is often defined as the strategyadoptedbyfirmsengagedinoverseasactivities(WelchandLuostarinen,1993).1 Internationalizationmaytakevarious forms, namely: (1) direct exports; (2) indirectexports (i.e. sales of goods through a third domesticparty that exports); (3) non-equity contractualagreements; and (4) foreign direct investment (FDI)andotherformsofequityagreements.

First,SMEscandirectlyserve internationalmarketsbybeginningtoexporttodistributorsortofinalconsumerslocatedinforeignmarkets.Second,SMEsmayoptforanindirect internationalization strategy by providing partsand components or services to other domestic firmsparticipatinginregionalorglobalvaluechains(GVCs)orbysellingproductsorservicestoexportintermediaries,suchaswholesalers,exportbuyingagentsandbrokers,situated in their own countries, who in turn export tointernational markets. Third, SMEs may opt for non-equitycontractualmodes,suchasfranchising,licensingor more structural alliances (e.g. export consortia).Fourth, SMEs can engage in FDI through greenfield investment (i.e. a type of FDI by which a parentcompany foundsanewventure ina foreigncountrybyconstructingnewoperationalfacilitiesfromscratch)andthrough mergers and acquisitions, as well as throughco-investment with other firms, such as joint ventures,withdifferentcontrollevels(e.g.fromminoritysharesto100percentowned).

While SMEs can use one or more of these types ofinternationalization modes, trade, direct or indirect, isoftenconsideredtobethefirststeptowardsengagingin international markets, operating as a platform forgreater future international expansion. Exportingindirectly is typically considered to be the least riskyentry mode to international markets because itenablesSMEstogainaccesstointernationalmarketswithout having to bear the upfront costs (including“sunk”costs, i.e.costs thatcannotberecoveredonceincurred)associatedwithsearchingfornewcustomersand negotiating contracts. Export intermediaries orother firms which undertake transaction sales and/or services in overseas markets on behalf of SMEsbenefit from market knowledge and negotiation skillsthat allow business risks to bepooledand diversifiedand that reduce the searching and matching costsassociatedwithexporttransactions.

Exporting is viewed as less risky than contract- orinvestment-based internationalization strategiesbecause it requires a lesser commitment oforganizational resources, entails fewer financial andcommercial risks,andallowsforgreater flexibilityandmanagerialdiscretion(LagesandMontgomery,2005).In practice, some SMEs export both directly andindirectly, highlighting the potential complementarity

betweenbothforeignmarketentrymodes(Nguyenetal.,2012).

Other forms of internationalization, such as non-equitycontracts and FDI, entail larger fixed costs, which aremore difficult to reverse in particular for SMEs. That iswhySMEs that have chosen in recent years toexpandtheir research and development (R&D), productionand distribution into foreign markets, tend to resort tocontractual arrangements, such as outsourcing, andminority share investment positions, rather than fullownershipofforeignaffiliates(Hollenstein,2005;Nakosand Brouthers, 2002). Since SMEs tend to experiencegreater financial, human and management constraintsthan large companies, and are more adverselyaffected by higher market barriers, it is not surprisingthat exporting continues to be the most commoninternationalization formadoptedby them(Riddleetal.,2007; Westhead, 2008). For instance, less than 3 percent of SMEs located in the European Union have aforeignsubsidiaryoverseas,which is significantly lowerthantheshareofSMEsexportingwithinandoutsidetheEuropeanUnion(EuropeanCommission,2014a).

The availability of data on international trade byenterprise size is limited in many respects. Forthe most part, researchers must rely on a mix ofenterprise surveys and administrative data, with all ofthe compromises that using different data sourcesentail (e.g. incomplete country coverage, inconsistentdefinitions of SMEs across datasets, differences inreportingstandardsacrosscountries,timelinessofdata,etc.).Detailed firm-level datamayalsobe inaccessibledue to confidentiality concerns. The main datasetsused in this sectionof the report are theOrganisationforEconomicCo-operationandDevelopment(OECD)’sTrade by Enterprise Characteristics (TEC) database,whichmostlydealswithdevelopedeconomies,2andtheWorldBank’sEnterpriseSurveys,whichprovidedetailedinformation on a range of developing economies.3These data sources are supplemented with others asnecessary,includingexistingstudiesonSMEs,nationalstatisticsandprivatesectorreports.

A number of findings emerge from this section. WeobservethattheparticipationofSMEsininternationaltrade varies considerably across countries,geographical regions, sectors and enterprise sizeclasses inbothdevelopedanddevelopingeconomies.In developed countries, shares of MSMEs in exportsand importsare relatively small compared to thoseoflargefirms,butthetradeparticipationofmedium-sizedfirmsisgreaterthanthatofmicroorsmallenterprises.A relatively small fraction of SMEs in developingeconomies export, either directly or indirectly,comparedtolargefirms.GVCparticipationofSMEsindevelopingcountriesisespeciallylowinsomeregions,

31

B. S

ME

s IN IN

TER

NA

TION

AL

TRA

DE

: ST

YLIZ

ED

FAC

TSLEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

andfirmswithfeweremployees indevelopingregionsalso take longer toaccess internationalmarkets thanlargerfirms.

Despite these disadvantages, new technologies areenhancing trade opportunities for smaller firms indeveloped and developing countries alike. Unliketraditional SMEs, a very high percentage of Internet-enabled SMEs engage in international trade. Thissuggests that increasing SMEs’ access to onlineplatforms could potentially raise exports of smallerenterprises, particularly in developing economieswhere Internet access is less widespread than indevelopedcountries.

Finally, available data on SMEs and trade areinsufficient to answer many outstanding questions,in particular questions about the extent of indirectparticipationintradebySMEsandtheirroleinGVCs.

1. SMEinvolvementindirecttrade

“Direct exports” occur whenever an enterprise sellsgoods or services directly to customers in anothercountry.Sincethereisnointermediary,amajorbenefitofexporting inthisway isthattheexportingfirmis indirect contact with its consumers, enabling a betterunderstanding of their needs, thereby creating newbusiness opportunities. In addition, direct exportsprovidefirmswithmoreprotectionoftheirtrademarksorpatentsincaseofinnovativeproducts.

SMEs can export directly if they have the means toreach foreign consumers or GVC partners locatedabroad. However, they may find it difficult to mobilizeall the necessary human and financial resourcesto develop their international trade activities. Thus,exporting can be challenging for SMEs, especially indevelopingeconomies.

This subsection provides details on the directparticipationofSMEsininternationaltradebyfirmsize,sector,and,fordevelopedeconomies,wherepossible,bypartnercountryandregion.

As noted in section A.1, there are no universallyaccepted definitions of enterprise size classes.By default in this report, firms with fewer than 10employeesarereferredtoas“micro”enterprises,firmswith between 10 and 49 employees are classifiedas “small” enterprises, firms with between 50 and249 employees are categorized as “medium-sized”enterprises,andfirmswith250ormoreemployeesareconsidered “large”. These size classes correspond tothose used in the OECD TEC database, but differentcategories will be used in other contexts dependingon the definitions used in particular databases or

studies.Forexample,thecategoriesabovedifferfromthoseemployedby theWorldBank in theirEnterpriseSurveys, in that the latter excludes firms with fewerthan 5 employees and businesses with 100 or moreemployeesfromitsdefinitionofSMEs.Otherdefinitionsarealsoused in researchandstatisticsonSMEs,butnearly all of these encompass businesses with fewerthan500employees.Consequently,thereadershouldbeaware that the termsSMEmay refer todifferentlysized firms in different contexts. The term MSME,referring to “micro, small and medium enterprises”, isalso used in this section and elsewhere in the reportto indicate the inclusionofmicroenterprises in totalswherepossible.

The TEC database provides breakdowns of exportsand imports by economic sector and by partnercountry/region.Tradevalues in theTECdatabasearerecordedincurrentUSdollars,facilitatingaggregation,but country coverage is mostly limited to developedeconomies.Onenotableexception isTurkey,which isusually classified as a developing/emerging economybutissometimestreatedasdevelopedbecauseit isamemberoftheOECD.

The World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys provide detailedinformation by sector and enterprise size for a widerangeofdevelopingcountries,but thedatasuffer fromsomeof thecommonshortcomingsofsurveys,suchasincompleteanswersfromrespondents.AnotherlimitationoftheEnterpriseSurveysisthatthetradevaluesareinnationalcurrencytermsandarelaggedtothefiscalyearprior to that during which the survey was carried out.Convertingtodollarsforaggregationpurposesisanon-trivial exercise, but this has been carried out to arriveat aggregate estimates for least-developed countries(LDCs)andotherdevelopingregions.

Due to differences in coverage and data sources, itis currently not possible to compare the participationof SMEs in developed economies with those in thedevelopinggroup.

(a) DirectparticipationofSMEsandMSMEsintradeofdevelopedcountries

DespitethefactthatMSMEsmakeupthevastmajorityof firms in developed economies (98 per cent ofindustrial firms in OECD countries, according to theTEC database), their direct exports typically accountfor less than half of the value of gross exports. Thisis illustrated by Figure B.1, which shows shares ofSMEs (i.e. excluding micro firms with fewer than 10employees) and MSMEs (i.e. including micro firms)trading with OECD economies. Shares of SMEs intrade were below 50 per cent in every country ontheexportside,andallbutonecountryonthe import

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

32

side. Includingmicrofirmswith0-9employeesboostsMSME shares in exports over 50 per cent in a fewcases, but shares of most countries remain below50percent.

(i) Directtradebyenterprisesize

Exportshares forMSMEssignificantlyexceed50percent inasmallnumberofcountries, includingEstonia(69 per cent), Turkey (63 per cent), Cyprus (61 percent) and Ireland (57 per cent). With the exceptionof Turkey, all of the countries with the highest SME

shares inexportvaluesaremembersoftheEuropeanUnion. By comparison, shares for non-EU countriessuch as Canada (29 per cent) and the United States(28percent)areconsiderablylower(seeFigureB.1).

Shares of MSMEs in gross imports tend to besomewhat larger than their shares in exports, withthe largest shares belonging to small countries suchasEstonia (78per cent),Cyprus (75per cent),Malta(74percent)andLatvia(63percent).However,theseenterprisesstillaccountforlessthanhalfofthevalueofimportsinthelargestdevelopedcountries,including

Figure B.1: SME and MSME shares in the dollar value of exports and imports of selected developed countries, 2013 (or latest year)(percentage)

Exports

SMEs (excluding firms with 0-9 employees) Other enterprises MSMEs (including firms with 0-9 employees)

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Estonia Ita

ly

Cypru

s

Turke

y

Portug

al

Croati

aLatv

ia

Nether

lands

Spain

Austria

Slovak

Rep

ublic

Lithua

nia

Denmark

Bulgari

a

Greec

e

Irelan

d

Sloven

ia

Roman

ia

Finlan

d

Belgium

Poland

Malta

France

Sweden

Luxem

bour

g

Hunga

ry

United

King

dom

Canad

a

German

y

Czech

Rep

ublic

United

Stat

es

47 45 44 42 41 37 36 35 34 33 33 33 33 33 31 30 27 27 27 26 25 25 24 24 21 21 20 18 18 17 15

69

51

61 63

5148

53

43 4348

42 4339

43 41

57

36 34 30 31 30

46 44

35

26

46

33 2921 20

28

Imports

SMEs (excluding firms with 0-9 employees) Other enterprises MSMEs (including firms with 0-9 employees)

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Cypru

s

Estonia

Croati

a

Portug

al

Denmark

Austria

Irelan

d

Bulgari

a

Sloven

ia

Finlan

dIta

ly

Lithua

niaLatv

ia

Roman

ia

Nether

lands

Luxem

bour

g

Slovak

Rep

ublic

Greec

e

Turke

y

Sweden

Poland

Malta

France

Spain

Belgium

Czech

Rep

ublic

Hunga

ry

Canad

a

United

King

dom

German

y

United

Stat

es

56 48 45 42 42 41 41 40 38 38 37 37 37 36 36 35 33 32 32 31 31 30 29 29 27 27 26 26 25 23 16

75 78

59 5651

61 6153 51

48 44 49

63

46 46 45 47 4439

50

37

7450

4032 31

4839

41

28 26

Note:Bulgaria,Canada,Ireland,Romania,SloveniaandTurkeyreferto2012,whileLuxembourgrefersto2011.

Source:OECDTECdatabase.

33

B. S

ME

s IN IN

TER

NA

TION

AL

TRA

DE

: ST

YLIZ

ED

FAC

TSLEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

Germany(28percent)andtheUnitedStates(26percent).

In aggregate, the share of MSME exports in totalexports of developed countries in the TEC databasein 2013 was 34 per cent. The equivalent share onthe import side was 38 per cent. Note that theseshares includeTurkey,which isusuallyclassifiedasadevelopingeconomybutisamemberoftheOECD.

Despite relatively small shares of SMEs in developedcountries’ exports and imports by value, MSMEs (and

micro firms in particular) represent the large majorityof trading firms inmostdevelopedeconomies.This isillustratedbyFigureB.2,whichshowsthepercentageof exporting and importing firms that are MSMEs inselected developed economies by enterprise size in2013 or the latest available year. Shares of MSMEsare lowest in countries with large numbers of firmsof unknown size (e.g. Belgium, Czech Republic andGermany). However, MSMEs account for as much as99 per cent of exporting and importing firms in theNetherlands and more than 95 per cent in Sweden.Shares are considerably smaller if micro firms

Figure B.2: Percentage of exporting and importing firms that are SMEs in selected developed economies by enterprise size, 2013 or latest year(percentage)

Exports Imports

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Romania

Turkey

Canada

Lithuania

Malta

Croatia

Bulgaria

United Kingdom

France

Poland

Austria

Greece

United States

Portugal

Italy

Denmark

Luxembourg

Finland

Sweden

Latvia

Hungary

Slovak Republic

Germany

Ireland

Estonia

Cyprus

Spain

Netherlands

Slovenia

Belgium

Czech Republic

SMEs (10-249) Micro enterprises (0-9) Large enterprises (250+) Number of employees unknown

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Turkey

Canada

Lithuania

France

United States

Romania

United Kingdom

Croatia

Bulgaria

Poland

Italy

Hungary

Greece

Latvia

Malta

Austria

Denmark

Ireland

Luxembourg

Portugal

Estonia

Germany

Slovak Republic

Sweden

Czech Republic

Finland

Netherlands

Cyprus

Slovenia

Spain

Belgium

Note:Bulgaria,Canada,Ireland,Romania,SloveniaandTurkeyreferto2012,whileLuxembourgrefersto2011.

Source:OECDTECdatabase.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

34

(0-9 employees) are excluded, ranging from 8 percentto48percent.Bycomparison,smallenterprises(10-249 employees) account for more than half ofexporting and importing firms in most countries intheTECdatabase.Intotal,theshareofMSMEsinthenumber of exporting and importing firms was 78 percentontheexportsideand76percentontheimportsidein2013(orlatestyear).

Small enterprises in the OECD TEC database maybe more representative of SMEs than either microor medium-sized firms, since the former frequentlyoperate in non-tradable sectors while the lattersometimes resemble larger firms more closely. Thisis especially true when comparing TEC data to theWorld Bank’s Enterprise Surveys, which classifyestablishments with more than 100 employees aslarge enterprises. Focusing on small enterprisesexclusively, we see that their overall share in exports(9percent)issignificantlylessthantheirshareinthenumber of exporting firms (21 per cent). Their sharein imports (11 per cent) is also less than their sharein importing firms (16 per cent), but not dramaticallyso. Meanwhile, medium-sized businesses account foragreaterfractionofinternationaltrade(15percentofboth exports and imports) than their numbers wouldsuggest (7 per cent of enterprises that export and 5percentofthosethatimport).

Ifwerestrictourattentiontoindustrialenterprises,wecan see a positive association between enterprise-size SMEs and participation in international trade.This is shown for developed OECD countries in

FigureB.3.The lowshares formicro firmswith fewerthan10employees(9percentontheexportsideand12 per cent on the import side) have dragged downaverage figures for all size classes due to the largenumber of micro firms in OECD economies. All ofthe other enterprise size classes (small, medium andlarge) have above-average shares of firms engagingin international trade, ranging from 38 per cent to66 per cent on the export side and 40 per cent to70percentontheimportside.Inparticular,exportandimportparticipationratesformedium-sizedenterprisesapproachthoseoflargeenterprises,whileparticipationratesforsmallandmicroenterprisesareconsiderablysmaller.

Insummary,sharesofSMEsandMSME’sintradeflowsof developed OECD countries are generally low, butthere is considerable heterogeneity across enterprisesize classes. In particular, rates of export and importparticipation for medium-sized enterprises are quitehigh,approachingthoseoflargebusinesses.

(ii) DirecttradeofMSMEsbysectorandpartner

Dollar values of trade flows by firm size and sectorare shown in Figure B.4 through 2012, the last yearfor which a complete sectoral breakdown wasavailable in the TEC database for a sufficient numberof countries. Micro enterprises appear to have thelargestshares inexports incertainservicescategoriesincludingaccommodation,arts/entertainment/recreationand other service activities, while large enterprises

Figure B.3: Percentage of industrial firms that are exporting and importing by enterprise size, 2013 or latest year(percentage)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Exports Imports

Total

17 20 9 12 38 40 58 62 66 70

0-9 10-49 50-240 250+

Note:DataforCanadaandIrelandreferto2012.Turkeyisexcludedduetomissingdata.

Source:OECDTECdatabase.

35

B. S

ME

s IN IN

TER

NA

TION

AL

TRA

DE

: ST

YLIZ

ED

FAC

TSLEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

predominate in sectors such as manufacturing andmining/quarrying. On the import side, micro firms aredominantinservicesectors,includinghealthcare,whilelarge firms account for an outsized share of financialservices imports. There does not appear to be anysystematic relationship between economic sectors andenterprise size other than the fact that more capital-intensivesectors(mining,manufacturing,electricityandgassupply)tendtobedominatedbylargeenterprises.Atahigherlevelofaggregation,itappearsthatmostMSMEexportsandimportsindevelopedeconomiesareinfact

services,with68percentontheexportsideand83percenton the importside (seeFigureB.5,alsowithdatathrough2012).

Two findings regarding the services trade of SMEsare worthy of note. First, those SMEs that begin toexporttendtopersistinthisbehaviour,i.e.theyhaveahighsurvival rateconditionaluponexporting.Second,although a smaller fraction of SMEs engage in tradecompared to large firms, those SMEs that do tradedirect a larger share of their sales toward foreign

Figure B.4: Trade values by sector, exports and imports, 2012(percentage)

Exports

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

59

9 25

14 23 2621 19

5341

5

71

47

118 15

10 15 4 2

53 46 44 41 38 38 35 32 28 24 18 18 16 13 9 8 8 7 3

937970

42

121

79

29

5

5

22

62

13

32322030

3717

29

3 5 3 13 9 11 5 6 2

65 6080 72

17 12 44

Wat

er s

uppl

y; s

ewer

age,

was

te/

rem

edia

tion

Agr

icul

ture

, for

estr

y an

d fis

hing

Tran

spor

tatio

n an

d st

orag

e

Con

stru

ctio

n

Who

lesa

le, r

etai

l tra

dean

d re

pair

Pro

fess

iona

l, sc

ient

ific

and

tech

nica

l act

iviti

es

Info

rmat

ion

and

com

mun

icat

ion

Art

s, e

nter

tain

men

tan

d re

crea

tion

Acc

omod

atio

n an

dfo

od s

ervi

ces

Acc

omod

atio

n an

d fo

odse

rvic

es; n

on-m

arke

t ser

vice

s

Oth

er s

ervi

ce a

ctiv

ities

Fina

ncia

l and

insu

ranc

e ac

tiviti

es

Man

ufac

turin

g

Edu

catio

n

Adm

inis

trat

ive

and

supp

ort

serv

ice

activ

ities

Rea

l est

ate

activ

ities

Hum

an h

ealth

and

soci

al w

ork

activ

ities

Ele

ctric

ity, g

as, s

team

and

air c

ondi

tioni

ng

Min

ing

and

quar

ryin

g

Pub

lic a

dmin

istr

atio

n, d

efen

ce;

soci

al s

ecur

ity

Imports

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Wat

er s

uppl

y; s

ewer

age,

was

te/

rem

edia

tion

Agr

icul

ture

, for

estr

y an

d fis

hing

Tran

spor

tatio

n an

d st

orag

e

Con

stru

ctio

n

Who

lesa

le, r

etai

l tra

dean

d re

pair

Pro

fess

iona

l, sc

ient

ific

and

tech

nica

l act

iviti

es

Info

rmat

ion

and

com

mun

icat

ion

Art

s, e

nter

tain

men

tan

d re

crea

tion

Acc

omod

atio

n an

dfo

od s

ervi

ces

Acc

omod

atio

n an

d fo

odse

rvic

es; n

on-m

arke

t ser

vice

s

Oth

er s

ervi

ce a

ctiv

ities

Fina

ncia

l and

insu

ranc

e ac

tiviti

es

Man

ufac

turin

g

Edu

catio

n

Adm

inis

trat

ive

and

supp

ort

serv

ice

activ

ities

Rea

l est

ate

activ

ities

Hum

an h

ealth

and

soci

al w

ork

activ

ities

Ele

ctric

ity, g

as, s

team

and

air c

ondi

tioni

ng

Min

ing

and

quar

ryin

g

Pub

lic a

dmin

istr

atio

n, d

efen

ce;

soci

al s

ecur

ity

71

929

2519 27

7 11

71

22 17

66

8 6 131

22

8265

268

53 48 45 4431 31 24 23 22 22 20 17 17 14 14 13 10 9 5

8880

6

215

6381

20

72

3

18

50 43

5

52

12

2329231318

2 6 7 6

50

5 6 2

50

1 1 1

59

3 74

SMEs (10-249) Micro enterprises (0-9) Large enterprises (250+) Number of employees unknown

Source:OECDTECdatabase.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

36

markets than large firms.These findingsbyLejárragaet al. (2014) could have important policy implicationsregarding the effectiveness of support for SMEs inaccessinginternationalmarkets.

The vast majority of MSME exports in developedcountriesaredestinedforotherdevelopedeconomies,and most MSME imports also originate in developedeconomies.Chinaisthemainexception,accountingfor2.3 per cent of developed country exports and 7 percentof imports.This isshown inFigureB.6for2012,

thelastyearwithsufficientlydetaileddatabypartner.SharesofdevelopedcountriesaspartnersofMSMEsmaybeexaggeratedduetothefactthatintra-EUtradeis included in the chart. An alternative perspective isprovided by Figure B.7, which shows the same dataexcluding trade between members of the EuropeanUnion. In this case, China’s shares in exports andimports of developed county SMEs rise substantially,to 7 per cent and 22 per cent, respectively, as doshares of other emerging markets such as India, theRussianFederationandTurkey.

Figure B.5: Exports and imports of MSMEs by broad product category, 2012(percentage)

Exports Imports

Agriculture, fuels and mining products (2%)

Manufacturing (30%)Services (68%)

Agriculture, fuels and mining products (1%)

Manufacturing (17%)Services (83%)

Source:OECDTECdatabase.

Figure B.6: Exports and imports of SMEs in developed countries by partner, 2012(percentage)

Exports Imports

Germany (15.3%)

France (10.3%)

Italy (5.6%)

Belgium (4.5%)

United States (4.3%)

Switzerland (3.3%)

Austria (3.2%)

Poland (3.2%)

Russian Federation (2.8%)

Netherlands (5.6%)

United Kingdom(5.9%)

Other (19.1%)

Denmark (1.3%)

Turkey (1.4%)

Portugal (1.5%)

Hungary(1.5%)

Sweden(1.6%)

SlovakRepublic(1.8%)

China (2.3%)

CzechRepublic (2.7%)

Spain (2.7%)

Germany (15.4%)

Netherlands (11.2%)

Italy (5.9%)

Belgium (4.9%)

United Kingdom (4.0%)

United States (3.6%)

Spain (3.1%)

Czech Republic (2.8%)

Poland (2.6%)

France (6.5%)

China (7.0%)

Other (17.5%)

Denmark (1.1%)

Turkey (1.2%)

Hungary (1.5%)

Slovak Republic(1.5%)

Sweden (1.5%)

Japan(1.9%)

Switzerland(1.9%)

Austria (2.4%)

RussianFederation (2.5%)

Source:OECDTECdatabase.

37

B. S

ME

s IN IN

TER

NA

TION

AL

TRA

DE

: ST

YLIZ

ED

FAC

TSLEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

Oneconclusionthatmightbedrawnfromtheprecedingcharts is that MSMEs in developed countries, andparticularly micro SMEs, have more difficulty inbridging the trade gaps between themselves anddistantordissimilartradingpartners.

(b) DirectparticipationofSMEsintradeofdevelopingcountries

AsnotedinSectionA,SMEsplayanimportantroleineconomicandsocialdevelopment,particularlyinpoorercountries and LDCs. According to WTO calculations,based on data from World Bank Enterprise Surveys,out of more than 15,500 manufacturing and servicesfirms in 41 LDCs, 88 per cent were SMEs, includingsome59percentofsmallfirmsemployingfewerthan20people,and29percentofmedium-sizedfirmswith20-99employees.Ingeneral,theirdirectparticipationin international trade is low. According to WTOestimates,basedondatafromWorldBankEnterpriseSurveys for over 25,000 SMEs in the manufacturingindustry in developing economies, SMEs’ directexportsrepresentonaveragejust7.6percentoftotalmanufacturingsales.4Incontrast,largemanufacturingfirms,withmorethan100employees,directlyexported14.1percentoftheirtotalsales.

The involvement of SMEs in direct exports variessignificantly across developing regions. The highestshares were recorded in Developing Europe, wheretheyaccountedforaround28percentofoverallsalesbySMEs,and in theMiddleEast (16percent).Theseshares are much higher than in SMEs in Developing

Asia (8.7 per cent). SMEs in Africa exported directlyonly3percentoftheirtotalsales(seeFigureB.8).Asindicated above, the World Bank Enterprise surveysexclude micro enterprises (in the class size betweenzero and four employees). However, the World Bankhascollectedmicrofirmsurveysinselecteddevelopingcountries. Using these data, Box B.1 shows that inLDCs, direct involvement in trade of micro firms withlessthanfiveemployeesismarginal.

A sectoral analysis reveals that, in developingeconomies,SMEs’lowerparticipationindirectexportsthanlargerfirmsaffectsallmanufacturingsectors,withthe exception of the wooden furniture manufacturingindustryandthepublishingandprintingindustries(seeFigureB.9).Itshouldbenotedthathighershareswerein both cases predominantly due to SMEs in LDCs(66 and 30 per cent respectively). A considerablenumber of medium-sized firms in several LDCs, suchas Bhutan, Mozambique, Myanmar, Tanzania, Ugandaand Zambia, directly exported wooden sofas, beds,chairs, tables, etc. SMEs did not participate activelyin the direct exports of textiles and garments. Theirshareofdirectexportswasoftenlessthan5percent,well below the high percentages reported by largeenterprises. Another example is manufacturing ofofficeequipmentandelectronics,wherelargefirmsindeveloping economies exported directly, on average,around43percentoftheirtotalsales,comparedwith4percentbySMEs.

Participationbydevelopingeconomies’SMEsindirectservicesexportswasnegligible,atlessthan1percent

Figure B.7: Extra-EU exports and imports of SMEs in developed countries by partner, 2012(percentage)

Exports Imports

United States (13.7%)

Switzerland(10.6%)

RussianFederation

(9.0%)

China (7.4%)

Turkey (4.4%)

Norway (2.4%)

Japan (2.3%)

Other (45.2%)

Canada (1.4%)

India (1.7%)

Mexico (1.9%)

China (21.5%)

United States(10.9%)

RussianFederation

(7.6%)

Switzerland (5.8%)

Japan (5.7%)

Turkey (3.6%)

Other (37.5%)

Norway (3.4%)

India (2.4%)

Canada (1.0%)

Mexico (0.5%)

Source:OECDTECdatabase.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

38

of total services sales, comparedwith32per cent oflarge firms. The difference in performance with largeservices firms is striking, ranging from 16 per centin LDCs to peak to 40 per cent in large enterpriseslocated in other developing economies (seeFigureB.10).

In services, the highest share of direct exports bySMEs in developing economies was in transport (20per cent of total sales). In communications, including

the provision of Internet access, the contribution wasaround 4 per cent. In the accommodation sector, theshare of direct exports by SMEs was below one percent. In LDCs, virtually all SMEs in constructionactivities, often foreign-controlled, supplied thenational market. Finally, SMEs’ participation in directexports in higher-skilled services was marginal.Computer-related activities accounted for less than 1percentoftheirtotalsalescomparedwith23percentoflargefirms.

Box B.1: Participation of micro firms in exports in selected LDCs

Evidence from recentWorldBankMicro firmsurveys inselectedLDCsconfirms themarginalizationofmicrofirms(i.e.,lessthanfiveemployees)ininternationaltrade.Microfirmswereengagedindifferentsectorsoftheeconomyrangingfromfoodmanufacturingtotheretailandwholesaletradeandtheleathergoodsindustry,aswellas restaurantsand ITservices. In2013,outof the412surveyedmicro firms in theDemocraticRepublicof the Congo, only 6 per cent were engaged in exports. The share of exporting micro firms, whether inmanufacturingorservices,inBhutanandEthiopiawasevenlower,at3percentofthetotal.Finally,inMyanmar,lessthanonepercentofthe430surveyedmicrofirmsexportedtheirproductstoforeigncountries.

Microfirmswereyoung,havingstartedoperationsbetween2004and2005,andseveralwererunbyfemalesowners,withatleastsecondaryeducation.InMyanmar,halfoftheownersheldauniversitydegree;inEthiopia,onequarter.

Virtuallyallmicrofirmsweredomestically-ownedandtargetedthe localornationalmarket.Onlyahandful ineachcountryheld internationalcertificatesofproductsand/orprocesses.Whileseveralmicro-firmsusedtheInternettoreachtheirclientsorsuppliers,onlyafewhadtheirownwebsites,rangingfrom2percentinBhutanto20percentinEthiopia.

Figure B.8: SMEs’ shares of direct exports in total sales in the manufacturing sector, by developing region and in the LDCs(percentage of total sales)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

National sales Direct exports

Per

cent

age

Developing economies, of which:

DevelopingEurope

Middle East DevelopingAsia

Latin Americaand the Caribbean

Africa Least-developedcountries

Note:SMEs’sharesof indirectexportarenot included.DevelopingEuropecomprisesAlbania,BosniaandHerzegovina,Montenegro,Serbia,FormerYugoslavRepublicofMacedoniaandTurkey;DevelopingAsia includesallmembersof theWTO’sAsiaregionminusAustralia,JapanandNewZealand;LatinAmericaandtheCaribbeanincludesallmembersoftheWTO’sSouthandCentralAmericaandtheCaribbeanregionplusMexico(seeWTOdocumentWT/COMTD/W/212).DevelopingeconomiesandLDCsaredefinedintheTechnicalnotesandinWTO(2016).

Source:WTOestimatesbasedonWorldBankEnterpriseSurveys.

39

B. S

ME

s IN IN

TER

NA

TION

AL

TRA

DE

: ST

YLIZ

ED

FAC

TSLEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

Figure B.9: Direct exports by manufacturing sector and firm size in developing economies (percentage of total sales)

05

101520253035404550556065

Man

ufac

turin

g (IS

IC 1

5-3

7)

Pub

lishi

ng, p

rintin

g, re

prod

uctio

n of

reco

rded

med

ia (I

SIC

22

)

Furn

iture

and

oth

erm

anuf

actu

ring

(ISIC

36

)

Toba

cco

(ISIC

16

)

Mot

or v

ehic

les

and

othe

rtr

ansp

ort e

quip

men

t (IS

IC 3

4-3

5)

Pap

er a

nd p

aper

pro

duct

s (IS

IC 2

1)

Cok

e, re

fined

pet

role

um p

rodu

cts

and

nucl

ear f

uel (

ISIC

23

)

Food

(IS

IC 1

5)

Text

iles

and

garm

ents

(ISIC

17

-18

)

Fabr

icat

ed m

etal

pro

duct

s,ex

cept

mac

hine

ry (I

SIC

28

)

Rub

ber a

nd p

last

ics

prod

ucts

(ISIC

25

)

Off

ice

and

elec

tric

al m

achi

nery

, rad

io,

TV a

nd c

omm

unic

atio

n eq

uipm

ent,

med

ical

,pr

ecis

ion

and

optic

al n

.e.s

. (IS

IC 3

0-3

3)

Mac

hine

ry a

nd e

quip

men

t n.e

.s.

(ISIC

29

)

Che

mic

als

and

chem

ical

pro

duct

s(IS

IC 2

4)

Woo

d an

d w

ood

prod

ucts

(IS

IC 2

0)

Leat

her:

lugg

age,

han

dbag

s, s

addl

ery,

foot

wea

r, et

c. (I

SIC

19

)

Oth

er n

on-m

etal

lic m

iner

alpr

oduc

ts (I

SIC

26

)

Bas

ic m

etal

s (IS

IC 2

7)

SMES (<100 employees) Large (+100 employees)

Note:WTOestimatesbasedontheInternationalStandardIndustrialClassificationofAllEconomicActivities(ISIC),Rev.3.1.N.e.s.standsfor“notelsewherespecified”.

Source:WorldBankEnterpriseSurveys.

2. SMEinvolvementinindirecttradeandglobalvaluechains

Rather than exporting directly, SMEs may connectindirectly to global markets by supplying goods andservices to other domestic firms that export. SMEscan use the services of domestic intermediariessuch as agents or distributors to help market theirproducts in foreigncountriesand reachnewmarkets.However, goods and services produced by SMEs canalso be indirectly exported as intermediate inputsincorporatedinproductsexportedthroughlargerfirms.In the manufacturing sector, for example, SMEs maybe contracted to produce certain parts according tospecifications of other companies, often larger ones,andentervaluechains.

Over the last decades, rapid technological changes,coupled with more efficient and less costlytransportation means, have significantly affectedthe ways goods and services are produced and sold.Thanks to lower barriers to international trade, theproduction of goods and services, rather than takingplace in a single economy, is globalized and spreadoverfirmslocatedindifferentcountries,alongachain.TradeinGVCsmainlyreferstotheexchangeofgoods

Figure B.10: Shares of direct services exports by firm size and developing group(percentage of total sales)

SMEs in LDCs

SMEs in otherdevelopingeconomies

Large firmsin LDCs

Large firmsin other

developingeconomies

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45

Source:WTOestimatesbasedonWorldBankEnterpriseSurveys.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

40

and services along the production and distributionchains that are fragmented across countries. Theproduction sequence is often supplemented by alogisticsanddistributionnetworkinwhichintermediateandfinalproductscirculatewithinandacrosscountriesuntiltheyreachthefinalconsumptionmarket.AlthoughGVC trade relates essentially to the exchange ofintermediates, exports of final products always takeplacewithinthefinalstageofthechain.Basedontheinputs produced by upstream suppliers, the ultimateenterprise in the production chain, which may or maynot be the lead firm in the chain, completes the finalproductandsendsiteithertointernationaldistributors(wholesalersorretailers)orstraightforconsumptionintheimportingcountry.

Enterprises participate in GVCs in two ways relatedto the linkages with their foreign partners. Backwardlinkages correspond to the import of inputs fromenterprises in order to produce intermediate or finalgoodsandservicesfordomesticconsumptionorfurtherexport.Enterprisesmayalso import finalproducts forfurther distribution through national or internationalnetworks. Backward linkages represent the “buyer’s”perspectiveorsourcingsideinGVCs.Forwardlinkagesrepresent the “seller-related” measure or supply sidein GVC participation, when an enterprise exportsintermediates through the international productionchainorfinalproductstodistributioncircuits.

It isalsonecessary todistinguishbetweendirectandindirect forward linkages. An enterprise contributesdirectly to a GVC when it exports inputs to partnercountries along the production chain for moreprocessing (and subsequent domestic consumption)or further export through international networks.Direct exports of final products through internationaldistributionchainsarealsopartofGVCtrade.

The indirect forward participation in GVCs mainlyconcerns enterprises that provide intermediate or finalgoodsandservicestolargerdomesticfirmsforexportsthroughinternationalnetworks.Inthisway,anenterprisebehaves like an “indirect exporter” by contributing tothe production or distribution of goods and servicesexported by other domestic enterprises. Direct andindirectforwardparticipationinGVCsdealwithexportsofproductsforfurtherexchangeswithintheproductionordistributionchains.FigureB.11 illustrates theabovedefinitions and shows the domestic and internationaltradeflowsrelatedtoGVCs.

(a) IndirectexportsandGVCparticipationofSMEsindevelopedcountries

OnlyafewstudieshaveexaminedtheroleofSMEsinindirectexports. Ina reporton the involvementofUScompanies in international supply chains, Slaughter(2013) stated that US multinational enterprisesin a typical year purchase inputs valued at morethan US$ 3 billion from SMEs in the United States,equal to 25 per cent of total input purchases. Otherestimates from the United States International TradeCommission (USITC) (2010) indicate that in 2007the share of SMEs in gross exports rose from 28per cent to 41 per cent once indirect exports wereconsidered. A similar study on Canadian SMEs fromIndustry Canada (2011) produced estimates showingthat 26 per cent of manufacturing enterprises soldinputs to other Canadian enterprises that were usedin the production of final goods for export. However,Canadian SMEs were actually less likely than largerenterprises to export intermediate goods indirectly.Specifically, 26 per cent of small enterprises and 27percentofmedium-sized firmsexported intermediategoods indirectly, compared to 30 per cent of largeenterprises.

Figure B.11: Schematic presentation of GVC trade flows

Import of intermediate/final goods/services(Backward GVC participation)

Reporting country

Entreprise 1Producer/distributorIndirect GVC exporter

Entreprise 2Producer/distributorDirect GVC exporter

Export of intermediate/final goods/services for:

Further production/distributionwithin GVCs(Forward GVC participation)

Final consumption

Intermediate/final goods/services

Source:WTOSecretariat.

41

B. S

ME

s IN IN

TER

NA

TION

AL

TRA

DE

: ST

YLIZ

ED

FAC

TSLEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

Official enterprise surveys and business-related datasources such as Trade by Enterprise Characteristics(TEC), Services Trade by Enterprise Characteristic(STEC) or Structural and Demographic BusinessStatistics(SDBS)providerelevantinformationonSMEtradeandotherdomains likeproduction,employment,productivityorconsumptionbuttheydonotnecessarilycontaindetailstodelineatetheactualactivityofSMEsindirectexportsandwithinGVCs.

An alternative is to use the value added approachto trade, which allows the decomposition of grossexports into their domestic and foreign value addedcomponents, and tracking of trade in intermediatestaking place within GVCs. Currently, the OECD-WTO Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database providesestimatesonbackwardandforwardlinkagestoGVCsfor 61 reporters, 34 industries and seven historicalyears. For the time being, the global input-outputtable underlying TiVA and GVC participation datarelies on the hypothesis of the homogeneity of firmsand industries, meaning that all firms within a sameindustry are supposed to have the same productiontechnology and the same share of imported inputs.This does not match the wide variety of enterprisesengaged in GVCs (SMEs, multinational enterprises,processers,multinationalaffiliates).

An expert group on “Extended supply-use tables(E-SUT)” launched in2015by theOECD investigateswaystobetterreflecttheheterogeneityofenterprisesin the national Supply-Use Tables (SUTs) that areused to construct the global input-output table for

the TiVA database. The principle is to combine SUTswith business-related data sources, like TEC, SDBSor Foreign Affiliates Trade Statistics (FATS), to getE-SUTs that will expand the granularity of standardSUTsinseveraldomains(seeOECD,2015b).Basedonsuch developments, TiVA and related GVC indicatorswillbebrokendownby:

• Firm size (micro enterprises, SMEs, largeenterprises,multinationalenterprises).

• Ownership(domesticorforeign,usingFATS).

• Exportorprocessingintensity(companiesinvolvedornotinglobalproduction).

Figure B.12 presents the various data sources andproduction sequence that will be involved to producetrade invalueaddedandGVCstatisticsbyenterprisetype.

TheOECDcarriedoutexploratoryworktofigureoutthetypeof trade-in-value-added indicators thatmay resultfromthefutureextended-SUTs.TheexerciseconsistedinlinkingnationalbusinessstatisticsonSMEswiththeglobal input-output tables developed for the OECD-WTO TiVA initiative. The results were presented in anOECD-WorldBankGroup reportprepared for theG20TradeMinistersMeetingheld in Istanbulon6October2015(seeOECDandWorldBank,2015).

The contribution of SMEs to GVCs is broken downintodirectandindirectdomesticvalueaddedcontents

Figure B.12: Moving towards trade in value added and GVC participation by enterprise characteristics

National Supply-Use table (SUT)

Extended SUT (E-SUT)Bilateral trade matrices(merchandise and services)

TiVA and GVC indicators broken down by:– Entreprise size (SMEs, Large entreprises,...)– Entreprise type of ownership– Other variables

Trade by Entreprise Characteristics (TEC, trade in goods)

Services Trade by Entreprise Characteristics (STEC, trade in services)

Structural Business Statistics(SBS, employment data)

Foreign Affiliates Trade statistics(firm ownership)

Global Input-Output table

Source:WTOSecretariat.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

42

of exports. The direct approach measures thecontributionmadebyanSMEinasectorofactivitytothe production of goods and services for export. Thenotion of indirect value added exports correspondsto the domestic value added originating from SMEsin upstream industries that provide inputs to theexportingindustry.

Formostof theOECDcountriescovered in the report,SMEs accounted for more than 50 per cent of thetotal domestic value added exports in 2009. Generallyspeaking, the direct contribution of SMEs to domesticvalueaddedexportsispredominantoverindirectexports.However, the proportion between direct and indirectexports varies greatly between industries. As shown inFigure B.13, the direct exports made by SMEs in themotor vehicles industryaremarginal,whereasSMEs inother domestic sectors (manufacturing and services)contributemuchmoretotheexportsofthis industrybyprovidingcomponentsorintermediateservicestomotorvehicle exporters. Indeed, the direct contribution ofSMEstoexportsofthebusinessservicesindustryoftenexceeded40percentofthetotaldomesticvalueadded

exportedbytheindustryin2009formostofthereviewedcountries (see Figure B.14). Overall, when cumulatingthedirectexportsofSMEswithupstreamsuppliesfromothersectors,SMEsturnouttobethemainexportersofbusinessservicesinmanyOECDcountries.

(b) IndirectexportsandGVCparticipationofSMEsindevelopingeconomies

TheWorldBankEnterpriseSurveysallow the indirecttrade and potential activity of SMEs within GVCs tobe quantified. This subsection exploits the availableindicators to establish stylized facts for SMEs indevelopingeconomies.

(i) Indirectexports

AccordingtoWTOestimates,indevelopingeconomies,the indirect exports in the manufacturing sector ofSMEs were estimated, on average, at 2.4 per cent oftotalsales,alevelthreetimeslowerthantheestimatedshare of direct exports. Indirect exports account for

Figure B.13: SMEs’ share of total domestic value added contained in exports of motor vehicles, 2009 (percentage)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Austria

Belgium

Czech Republic

France

Germany

Hungary

Italy

Mexico

Netherlands

Poland

Portugal

Spain

Turkey

United Kingdom

United States

SMEs direct exports(SMEs belonging to motor vehicle industry)

SMEs indirect exports(upstream suppliers from other industries to motor vehicle exporters)

Source:OECDestimates.

43

B. S

ME

s IN IN

TER

NA

TION

AL

TRA

DE

: ST

YLIZ

ED

FAC

TSLEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

Figure B.14: SMEs’ share of total domestic value added contained in exports of business services, 2009 (percentage)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Austria

Belgium

Czech Republic

France

Germany

Hungary

Italy

Mexico

Netherlands

Poland

Portugal

Spain

Turkey

United Kingdom

United States

SMEs direct exports(SMEs belonging to business services industry)

SMEs indirect exports(upstream suppliers from other industries to business services exporters)

Source:OECDestimates.

Figure B.15: Shares of direct and indirect manufacturing exports by firm size in developing economies(percentage of total sales)

Indirect manufacturing exports

0

10

20

Per

cent

age

5

15

25

35

30

40

Direct manufacturing exports

SMEs Large firms(>100 employees)

2.4%

7.6%

12.6%

14.1%

Source:WTOestimatesbasedonWorldBankEnterpriseSurveys.

a much larger share of sales in large firms (14.1 percent), suggesting that they can adapt more easilyto product requirements, such as standards andcertification, made by other firms, or have a moreefficient network of intermediaries (see Figure B.15).Overall, in developing economies, SME participationin exports, direct and indirect, was estimated at only10 per cent of total manufacturing sales comparedwithsome27percentinlargerfirms.

SMEs in Developing Europe recorded the highestshare of indirect participation in exports, estimatedat around 9.3 per cent, followed by Developing Asia(3.7percent)andtheMiddleEast(2.4percent),whileAfricanSMEs,excludingLDCs,sawonly1percentoftheirtotalsalesexportedindirectly(seeFigureB.16).

At the product level, SMEs’ highest shares ofindirect exports were found in the manufacturingof various types of machinery, in the publishing andprinting industry and in paper and paper productsmanufacturing, as well as in the automotive industry,where international production is widely organized. Inallthesesectors,theshareofindirectexportsinSMEs’total sales largely outpaced that of large firms (seeFigure B.17). Large firms, by comparison, appeared

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

44

tobeheavilyengagedinthemanufacturingoftextilesand garments, office equipment and electronics,tobacco,glassandceramics.And,especially inLDCs,leathergoodsandfootwear.

Services SMEs in developing economies participatedmore in indirect exports than in direct exports.However,theiroverallparticipationinservicesexportsis marginal, at 4 per cent of total services sales. Itis interesting to note that large firms in developingeconomies supply services to foreign consumerspredominantlythroughdirectexports(seeFigureB.18).

(ii) GVCparticipation

The opportunities for SMEs in global value chainsare enormous. Participation in value chains exposesthem to a large customer/buyer base, as well asto opportunities to learn from large firms and fromengagingandsurviving in thehotlycontestedsectorsof the global marketplace. The penetration of globalvalue chains, however, also presents huge and oftendauntingchallengesforSMEs(ADB,2015).

Unfortunately,dataonSMEstradeinGVCsarescarce.Official business data sources, like TEC, STEC or

Figure B.16: SMEs’ shares of indirect exports in total sales in the manufacturing sector, by developing region and in LDCs(percentage of total sales)

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

Indirect exports (sold domesticallyto a third party that exports)

Direct exports

Percentage

DevelopingEurope

Developing Asia

MiddleEast

Latin Americaand the Caribbean

Africa

LDCs

Note:SMEs’sharesofnationalsalesareexcluded.SeenotesofFigureB.8fordetailsoncountrygroups.

Source:WTOestimatesbasedonWorldBankEnterpriseSurveys.

Figure B.17: Indirect exports by manufacturing sector and firm size in developing economies (percentage of total sales)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Man

ufac

turin

g (IS

IC 1

5-3

7)

Pub

lishi

ng, p

rintin

g,re

prod

uctio

n of

reco

rded

med

ia (I

SIC

22

)

Mac

hine

ry a

nd e

quip

men

t n.e

.s. (

ISIC

29

)

Pap

er a

nd p

aper

pro

duct

s (IS

IC 2

1)

Mot

or v

ehic

les

and

othe

r tra

nspo

rt e

quip

men

t (IS

IC 3

4-3

5)

Food

(IS

IC 1

5)

Leat

her g

oods

: lug

gage

, han

dbag

s,sa

ddle

ry, f

ootw

ear,

etc.

(IS

IC 1

9)

Text

iles

and

garm

ents

(IS

IC 1

7-1

8)

Rub

ber a

nd p

last

ics

prod

ucts

(IS

IC 2

5)

Toba

cco

(ISIC

16

)

Bas

ic m

etal

s (IS

IC 2

7)

Off

ice

and

elec

tric

al m

achi

nery

, rad

io, T

Van

d co

mm

unic

atio

n eq

uipm

ent,

med

ical

,pr

ecis

ion

and

optic

al n

.e.s

. (IS

IC 3

0-3

3)

Cok

e, re

fined

pet

role

um p

rodu

cts

and

nucl

ear f

uel (

ISIC

23

)

Furn

iture

and

oth

er m

anuf

actu

ring

(ISIC

36

)

Fabr

icat

ed m

etal

pro

duct

s,ex

cept

mac

hine

ry(IS

IC 2

8)

Che

mic

als

and

chem

ical

pro

duct

s (IS

IC 2

4)

Woo

d an

d w

ood

prod

ucts

(IS

IC 2

0)

Oth

er n

on-m

etal

lic m

iner

al p

rodu

cts

(ISIC

26

)

SMES (<100 employees) Large (+100 employees)

Note:BasedontheInternationalStandardIndustrialClassificationofAllEconomicActivities(ISIC),Rev.3.1.N.e.s.standsfor“notelsewherespecified”.

Source:WTOestimatesbasedonWorldBankEnterpriseSurveys.

45

B. S

ME

s IN IN

TER

NA

TION

AL

TRA

DE

: ST

YLIZ

ED

FAC

TSLEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

Figure B.18: Shares of direct and indirect services exports by firm size in developing economies(percentage of total sales)

0

10

20

Per

cent

age

5

15

25

35

30

40

Indirect manufacturing exportsDirect manufacturing exports

SMEs Large firms(>100 employees)

0.9%

2.6%

31.9%

4.2%

Source:WTOestimatesbasedonWorldBankEnterpriseSurveys.

SDBS,donotalwayscoverGVCactivityandtheyfocuslargelyondevelopedeconomies.

The World Bank Enterprise Surveys shed light onSMEs’ potential activity within GVCs in developingeconomies. The indicator within the EnterpriseSurveys, “Percentage of material inputs and/orsupplies of foreign origin” refers to the upstreamlinkages that SMEs set up with foreign partners toget inputs for their production and related exports.This indicator is used as a proxy for the backwardparticipation inGVCs.Averagebackwardparticipationwascalculatedastheaverageofforeigninputsusedinthemanufacturingprocess foreacheconomy,by firmsizeandbymanufacturingsector.

On the supplier side, two indicators are combined toapproximate SMEs’ forward participation to GVCs,namely the “Sales exported directly as percentageof total sales” and the “Sales exported indirectly aspercentage of total sales”. However, such indicatorspresentsomelimitsinoutliningtheactualroleofSMEsin GVCs, as they do not give information on the end-use category of the exported goods and services.Although no distinction is made between exports ofintermediategoodsandservicesthatarefurtherusedalongtheproductionchain,andproductsdedicatedtofinalconsumption,thesetwoindicatorsareretainedtoestimate the potential of SMEs’ downstream linkagestoGVCs.

Over 33,000 surveyed establishments engaged inthe manufacturing sector in developing economiesreported the values of total sales, largely in localcurrencies, and their percentage breakdown intonational sales, direct exports, and indirect exports.Values of direct exports and of indirect exports werecalculated for each establishment then convertedinto US dollars. Direct exports and indirect exportsdatawere thenaggregatedtoprovideaveragesharesof direct exports and indirect exports for individualeconomies,furtherbrokendownbysizeoffirmandbymanufacturingsector.

According to WTO estimates, SMEs in themanufacturingsectorindevelopingeconomiesarenotactivelyengagedinGVCs.Participationismainlydrivenbyupstreamlinks(backwardparticipation),withSMEsimportinginputsneededinthemanufacturingprocessfrom abroad. However, only a limited part of SMEs’production is exported to foreign countries, whetherdirectlyorindirectly.AsshowninFigureB.19,thevastmajorityofSMEsindevelopingeconomiesarelocatedin the bottom left quadrant, suggesting a low GVCparticipation(lowbackward/forwardparticipation).

The low levels of integration of SMEs into GVCs areevidentespeciallyifcomparedwithlargemanufacturingfirms (Figure B.20). In Developing Asia and in LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean,largefirmsareintegratedinto GVCs, as shown by some economies’ very highvaluesofbackward/forwardparticipation.Bycontrast,SMEs in the region have a low forward participation,with most countries concentrated in the bottom-leftsquare in the chart, suggesting that they are not yetinvolved in GVCs. SMEs in Developing Asia also useonaveragefewerinputsofforeignorigin(FigureB.21).ThiscanbeexplainedbythefactthatAsia’sindustrialnetwork is more advanced than in other developingregions.Asianfirmsarethemselvesthemanufacturersof inputs/intermediate products, for foreign firms inparticular, in developed economies. Necessary inputsare largely availabledomestically and sodonot needtobeimportedfromabroad.

Estimates suggest that in Africa, it is not onlySMEs but also large firms that do not benefit fromparticipation in GVCs. Both SMEs and large firmsin several African economies show high backwardparticipation.Comparedwithotherregions,theyimportalargeshareofinputsfromforeigncountriesinorderto be able to manufacture their products. However,their forwardparticipation is the lowestacrossall thedeveloping regions. A sectoral analysis shows that,in general, SMEs’ poor integration in GVCs affectsall manufacturing industries, with the exception ofthe furniture-making sector, in which SMEs in LDCshave a high share of direct exports (as shown in the

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

46

previous subsection). By contrast, large enterprisesare relatively more connected to GVCs in severalsectors, in particular in the textiles and garmentsindustryandinthemanufacturingofofficeequipmentsuch as computers and electronic products. In theseindustries, developing economies have high levels offorwardparticipationinGVCs.Largefirmsalsoshowagoodlevelof integrationinGVCsintheleathergoodsmanufacturingindustry.

Figure B.20 also shows average backward/forwardparticipation in GVCs by firm size, manufacturingsector and ownership. FDI plays an important rolein firms’ integration to GVCs, whether small or large.Estimates show that foreign-owned SMEs have morelinkages to GVCs than domestic SMEs. These firmsimport more inputs to be used in the manufacturingprocess than domestic SMEs, showing higher levelsof backward participation in GVCs. In addition, theycan export a much larger share of their production(forward participation), and this applies to almost allmanufacturingexports.Forexample,intheautomotivesector, direct and indirect exports accounted for over40 per cent of SMEs’ total sales, while in domesticSMEs the share was around10 per cent. Similarly, inthe furniture manufacturing industry, which recordedthe highest share of direct export to total sales, thecontribution was essentially made by foreign-ownedSMEs.

3. SMEparticipationininternationale-commerce

The development of electronic commerce as ameans for firms to reach customers in overseasmarkets promises to dramatically expand exportopportunitiesforSMEsifcertainobstacles–includingthose related to information and communicationstechnology (ICT) infrastructure, and to the legal andregulatory environment, discussed in Section D.4– can be overcome. Retail businesses and serviceproviders such as Amazon, eBay, PayPal and othersnow provide platforms and payment systems thatfacilitate exports by even the smallest firms. Digitaltechnologies reduce trade costs for SMEs and givethem a global presence that was once reserved forlargemultinational firms,allowingsmallbusinesses tocompete directly with larger companies. Some of theservices that the Internet-based technologies havemade more accessible to SMEs include shipping/logistics, international payments, translation services,customerservicesandmarketresearch.

Thissection reviewsavailableevidenceonSMEtradeenabledbyinformationtechnology.Forthepurposesofthis report, e-commerce is defined as the production,advertising,saleanddistributionofgoodsandservicesvia telecommunication networks such as the Internet.

Figure B.19: SMEs in developing economies: backward and forward participation in GVCs(share in total sales and share in total inputs, percentage)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 1000

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Dire

ct a

nd in

dire

ct e

xpor

ts (f

orw

ard

part

icip

atio

n)

Use of foreign inputs in manufacturing (backward participation)

Hig

h G

VC

part

icip

atio

nH

igh

back

war

d G

VC

part

icip

atio

n

Hig

h fo

rwar

d G

VC

part

icip

atio

nLo

w G

VC

part

icip

atio

n

Note:EachsquarerepresentstheaverageGVCparticipationofSMEsinagivendevelopingeconomy.

Source:WTOestimatesbasedonWorldBankEnterpriseSurveys.

47

B. S

ME

s IN IN

TER

NA

TION

AL

TRA

DE

: ST

YLIZ

ED

FAC

TSLEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

Figure B.20: SMEs and large enterprises: backward and forward participation in GVCs by region, ownership and manufacturing sector(share in total sales and share in total inputs, percentage)

Source:WTOestimatesbasedonWorldBankEnterpriseSurveys.

Dire

ct a

nd in

dire

ct e

xpor

ts (f

orw

ard

part

icip

atio

n)

Use of foreign inputs in manufacturing (backward participation)

Large Linear (large)SMEs Linear (SMEs)

00 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Low GVCparticipation

High backward GVCparticipation

High forward GVCparticipation

High GVC participation

DevelopingAsia

Low GVCparticipation

High backward GVCparticipation

High forward GVCparticipation

High GVC participation

Dire

ct a

nd in

dire

ct e

xpor

ts (f

orw

ard

part

icip

atio

n)

Use of foreign inputs in manufacturing (backward participation)

Large Linear (large)SMEs Linear (SMEs)

00 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

DevelopingEuropeandtheMiddleEast

Low GVCparticipation

High backward GVCparticipation

High forward GVCparticipation

High GVC participation

Dire

ct a

nd in

dire

ct e

xpor

ts (f

orw

ard

part

icip

atio

n)

Use of foreign inputs in manufacturing (backward participation)

Foreign-owned SMEs Domestic SMEs

00 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Furnitureand other

manufacturing

Automotive

Officeequipment

and electronics

Chemicals,petroleum,

plastic

SMEsbysectorandownership

Low GVCparticipation

High backward GVCparticipation

High forward GVCparticipation

High GVC participation

Dire

ct a

nd in

dire

ct e

xpor

ts (f

orw

ard

part

icip

atio

n)Use of foreign inputs in manufacturing (backward participation)

Large Linear (large)SMEs Linear (SMEs)

00 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

LatinAmericaandtheCaribbean

Low GVCparticipation

High backward GVCparticipation

High forward GVCparticipation

High GVC participation

Dire

ct a

nd in

dire

ct e

xpor

ts (f

orw

ard

part

icip

atio

n)

Use of foreign inputs in manufacturing (backward participation)

Large Linear (large)SMEs Linear (SMEs)

00 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Africa

Low GVCparticipation

High backward GVCparticipation

High forward GVCparticipation

High GVC participation

Dire

ct a

nd in

dire

ct e

xpor

ts (f

orw

ard

part

icip

atio

n)

Use of foreign inputs in manufacturing (backward participation)

Foreign-owned SMEs Domestic SMEs

00 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100Textiles and

garments

Leather

Officeequipment and

electronics

Largefirmsbysectorandownership

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

48

E-commercecanbebrokendown into sales (e-sales)and purchases (e-purchases). In its survey on ICTusageinenterprisessurvey,theEuropeanUnionfindsthat purchases by companies are twice as frequentas sales.5 This section discusses cross-border onlinesales, as opposed to domestic online sales. It shouldbeemphasizedfromtheoutsetthatmoste-commercetodayisreportedtobedomesticcommerce,especiallyinlargeeconomies(McKinseyGlobalInstitute,2013a).Cross-border online transactions, as a share of totalonline sales to consumers, are significantly larger insomedevelopingcountries(e.g.morethan50percentin India and Singapore) than in developed countries(e.g.20percentforCanadaand18percentforJapan)(McKinseyGlobalInstitute,2013a).

The Internet has proved to be significantly moreamenabletoSMEsthanprivatebusinessnetworksthatpredated it. The United Kingdom Office for NationalStatistics has estimated that between 2009 and2013, SMEs web-based sales increased five timesfasterthansalesviaEDI(electronicdatainterchange)systems.eBayalsopublishedaseriesofstudies(eBay,2012; 2014; 2016) using data covering transactionson the eBay Marketplace since 2010. To ensure thatthe community of small commercial enterprises isproperly captured, and that small individual sellersare excluded, the data are limited to transactions bysellerswithannualsalesofmorethanUS$10,000(orlocal currency equivalents) on the eBay marketplace.Thesefirmsarereferredtoas“commercialsellers”,orsmallonlinebusinesses.Toallowforcomparisonswith“traditional”, non-Internet-enabled SMEs, eBay has

useddatafrompubliclyavailablesourcesincludingtheWorld Bank, Eurostat, and various national statisticalagencies.

Broadly, these studies find that the vast majority oftechnology-enabled small firms export: 97 per centof them on average, and up to 100 per cent in somecountries. By comparison, only a small percentage oftraditionalSMEsexports (between2percentand28percentforallcountriesexceptItalyandThailand,seeFigureB.22).NotonlydoInternet-enabledcommercialSMEs export at a high rate, they also reach a largenumber of foreign destinations. For example, SMEsin China typically export to 63 countries, and KoreanSMEstypicallyexportto57countries(FigureB.23).6

One difference between exporting SMEs and largeexporters is that shipments from SMEs are often oflow volumes and frequently consist of single itemsshippedthroughtraditionalmailorbyexpressdeliverycompanies. The rapid growth in shipments of parcelsby post offices (Figure B.24) could signify growingshipments by SMEs. Growth has been fastest indeveloped countries (average annual growth of morethan 10 per cent since 2005), but negative in Africa(-3.1percent)andstandsat0percentinAsiaandthePacificandinLatinAmerica.Onepossibleexplanationfor the low rates of postal delivery of packages inAfrica, Asia and Latin America is that shipments inthese regions may be conducted by express deliverycompanies and cost more than traditional mail. The40 per cent rise in the index of international expressdelivery volumes registered by the Global Express

Figure B.21: Use of foreign and domestic inputs in production of SMEs by developing region(percentage)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Domestic origin (% total inputs) Foreign origin (% of total inputs)

Middle East Africa Latin America and the Caribbean Asia

Source:WorldBankEnterpriseSurveys.

49

B. S

ME

s IN IN

TER

NA

TION

AL

TRA

DE

: ST

YLIZ

ED

FAC

TSLEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

Association (DHL, FedEx, TNT, and UPS) between2008and2013issuggestiveevidenceinthisregard.

Online buying and selling are relevant to trade inboth goods and services. Even when trade in goodsis involved, services also play a role. Online facilities,even those primarily offering merchandise, are alsoa form of retailing service. Moreover, online trade is

naturally relevant for services that can be deliveredelectronically. This encompasses such activities asprofessionalservices,businessprocessing,backofficeservicesanddigitalproductssuchassoftware,music,films, e-books and consultant reports. With the offerofonlinereservations,ticketing,trackingandcustomerservice, tourismwasamong the first services sectorsthatengagedsignificantlyinonlinebusiness.Asshown

Figure B.22: Share of eBay-enabled and traditional SMEs(percentage)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Italy

United

King

dom

Thail

and

Jord

an

Turke

yChin

aSpa

in

Repub

lic of

Kor

ea

Colombia

South

Africa

Chile

France

German

yBraz

il

Ukraine Ind

iaPer

u

Mexico

United

Stat

es

Indon

esia

Austra

lia

Canad

a

Traditional businesses eBay

Source:DataforallcountriesweresourcedfromeBay(2016)exceptJordan,PeruandUkraine,whichweresourcedfromeBay(2012),andTurkey,whichwassourcedfromeBay(2014).

Figure B.23: Number of export destinations of eBay-enabled SMEs

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

China

Thail

and

Repub

lic of

Kor

ea

Indon

esia

Ukraine

Turke

y

South

Africa

Brazil

Chile

Jord

anPer

uSpa

in

Mexico

Canad

aInd

ia

France

United

King

dom

United

Stat

es

Colombia Ita

ly

Austra

lia

German

y

63

57

46

3735 34

29 28 28 2825 24

21 20 20 20 19 18 1816

1412

Source:DataforallcountriesweresourcedfromeBay(2016)exceptJordan,PeruandUkraine,whichweresourcedfromeBay(2012),andTurkey,whichwassourcedfromeBay(2014).

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

50

inacasestudyon thesector inEgypt (KamelandElSherif,2001),SMEsparticipatedinthistrend.7

An increasing number of e-commerce platforms areset up or adapted with the specific goal of assistingSMEs or even individual sellers, such as freelancersor designers of arts and crafts.8 For example, Etsy,an online market for artisans and small producers,recorded US$ 2 billion in sales in 2014, with morethan one-third of those representing internationalsales (McKinsey Global Institute, 2015). Large retailplatformsandserviceproviderssuchasAmazon,eBayand PayPal now provide or are developing ancillaryservicesandpaymentsystemsto facilitateexportsbyeven the smallest sellers. Such online marketplacescanofferSMEsameans to scaleupatminimal cost,providing nearly instant solutions that include securepaymentsystems,logisticssupport,andglobalvisibilityofthekindoncereservedforlargefirms.