Augusto-Navarro 2013 Contexturas

-

Upload

estevao-batista -

Category

Documents

-

view

224 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Augusto-Navarro 2013 Contexturas

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 26

THE PONTENTIAL OF INTEGRATING GENRE ANALYSIS AND FOCUSED ATTENTION FOR DEVELOPMENTS IN EFL WRITING

Eliane Hercules AUGUSTO-NAVARRO UFSCar – Universidade Federal de São Carlos

RESUMO

Apresentamos neste artigo uma discussão sobre como a integração entre a análise de gêneros, com foco no nível micro estrutural (escolhas linguísticas), e a atenção focada (sensibilização), podem ser integradas, com resultados favoráveis, em atividades pedagógicas de produção escrita em língua inglesa para professores em formação. Palavras-chave: Sensibilização; Atenção Focada (grammaring); Análise de Genêros; Habilidade Escrita; LE

ABSTRACT

This paper presents a discussion of how a micro structural genre analysis combined with focused attention to language choices can be productively combined in pedagogical activities aiming at teaching EFL writing to prospective EFL teachers. Besides favorable results, it points out important variables to be considered in future research.

Keywords: Awareness; Focused attention (grammaring); Genre analysis; Writing; EFL

1. Introduction

When we think of language skills, writing tends to be one that presents learners with enormous challenges, even in first language (L1). One of the reasons for this difficulty, as pointed by Ferreira (2008, p.76), is that

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 27

there are widespread misleading ideas that writing well is a matter of reading a lot or, even more questionable, a natural gift. It is also undeniable that some discursive genres tend to be more difficult to accomplish than others, which is the case of academic writing, both in first language and in second or foreign language (L2 and FL, respectively), as evidenced by a large body of literature about writing in academic settings (Hyland, 2007; Paltridge, 1994, 1995, 2012; Motta-Roth, 2006; Ramos, 2004; Swales, 1983,1990, 1996, 2004, 2012; among many others). Writing to a discursive community1 (Swales, 1990, p.24) requires being able to meet its expectations in terms of content and form. Being able to actively participate in a community, by publishing the results of one’s studies, for example, is an aim for most researchers all over the world. However, this empowerment (Freire, 1987) practice has on many occasions an obstacle, that is, the difficulty faced by researchers when they try to write or deliver papers in a L2 or FL. At the same time, English has been widely recognized as the major language of sciences (Swales, 2012; Wood, 2001, among others). Although there has been a lot of research and publication about academic writing in L2/FL and also on genre analysis, reflections about practical pedagogical possibilities are far more scarce, at least in Brazil, as argued by Ramos (2004).

The aim of this draft is to contribute to this practical perspective by demonstrating and discussing how we have been productively combining the aspects of awareness raising, subjacent in the Swalesian genre analysis pedagogy, in association with this same phenomenon (awareness) in the theory of grammar(ing) as skill (Larsen-Freeman, 2003) to develop our students’ (prospective EFL teachers) skills in writing. It comprehends a twofold agenda, one regarding studying genre characteristics to facilitate the composition process and another about how to integrate grammar comprehension (understanding language choices) in communicative pedagogical units by focusing on specific genres. As discussed by Larsen-Freeman (2003), even when teachers focus on form and on communication, grammar and communication practice remain segregated, when they should be integrated. Both, Batstone (1994) and Larsen-Freeman (2003) acknowledge that there is a shortage of teaching

1 Swales (1990, p.24). Discouse Community is a key element in Swales’s definition of genre and refers to a group of people with

common interests, expertise and specific means of communication. Swales proposes six characteristcs to characterize a

discoursive community: 1) has a broadly agreed set of common public goals; 2) has mechanisms of intercommunication among its

members; 3) uses its participatory mechanisms primarily to provide information and feedback; 4) utilizes and hence possesses one

or more genres in the communicative furtherance of its aims; 5) in addition to owning genres, it has acquired some specific lexis,

and 6) has a threshold level of members with a suitable degree of relevant content and discoursal expertise.

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 28

materials that preview the integration of form and communication in language teaching and learning. As a consequence, many teachers will have no clue of how to deal with grammar and retain a focus on meaning at the same time.

This paper brings illustrations and discussions with potential to bring some contribution in filling this gap, as it discusses the importance of helping learners to pay attention to the choices (and their respective reasons) they have when writing in a given genres.

A first step in this respect is preparing learners to notice, as persuasively discussed by Schmidt (1990), how language operates in regard to its conveyed meanings. Noticing is also defended by Batstone (1994) and Larsen-Freeman (2003, albeit with the name of awareness raising). Schmidt (2001, p.5) also reminds us that “Even a cursory review of the SLA literature indicates that the construct of attention appears necessary for understanding nearly every aspect of second and foreign language learning.”.

Although we are aware that there are different degrees and understandings of the term awareness, as discussed by Schmidt (1990), in this paper noticing and awareness are used interchangeably, referring to paying focused attention to something (language in this case). Defending the importance of pedagogical developments and analysis, Svalberg (2012) discusses the importance of investigating how language awareness (which she calls LA) is developed in a process of engagement with the language (EWL). In her words:

To have an impact on language learning/teaching, LA research in the next ten years needs to provide a much richer picture of how LA is constructed (the EWL process), how it is applied in language learning classrooms in a wide variety of contexts, and how it affects language learning. (p.385, originally underlined).

The study reported here derives from observing 16 (Portuguese speakers) prospective EFL (English as a Foreign Language) teachers in a discipline on EFL writing from a teacher education undergraduate program (nationally named Letras) at a public university in Brazil. The aim of the discipline is developing participants’ writing skills and preparing them to become informed teachers of writing at the same time. Analysis of their writing assignments shows that a first challenge for the participants when writing, especially the academic genre (abstracts in this case), is at the micro level linguistic choices.

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 29

This paper brings a contribution exactly regarding the design and adoption of teaching materials following a LA and engagement perspective. The pedagogical practice discussed here consists of presenting students with a sequence of genres from more to less familiar and complex (as detailed in the methodology section). Texts belonging to the selected genres are analyzed and produced in different practical activities. These range from writing a piece of advertisement for a product that participants have “created” to writing an academic abstract to submit as a proposal to a conference on language teaching (for demonstrating a lesson that they have designed). In each case, participants’ production is preceded by an analysis of language choices in texts belonging to the same genre that they will be assigned to write. The rationale for this practice is the fact that a large body of research in the area of L2/FL has demonstrated that “both attention and awareness (and hence noticing) facilitate learning” (Svalberg, 2007, p. 289). The proposed activities have proved fruitful in promoting participants’ awareness regarding to language choices. The integration of a micro structural genre analysis and the perspective of noticing (Schmidt and Frota, 1986 and Schmidt, 1990) grammar(ing) as skill (Batstone, 1994 and Larsen-Freeman, 2003) is grounded on the fact that both theories propose learners’ awareness raising as significant to the learning process. This awareness will also help learners to understand that conveying meaning is a matter of language choice, that is, there are different ways to convey similar meanings. We have to understand such difference to choose how we want to express ourselves. As defended by both, Swales (1990) and Larsen-Freeman (2003), language and choice are not dissociable, and there are reasons (that should be considered) behind choices. Although in our study we have not analyzed the acquisition of any specific grammatical aspect of the language, our central question was how the participants would react to the proposition of awareness raising concerning language options in regard to specific genres. Data analysis reveals that participants have engaged with the language, and understood (became aware) the importance of respecting language choices in relation to the genre of a given text (especially in relation to purpose and target audience).

2. Genre analysis

In a recent volume of the Journal of Second Language Writing, devoted to discussing the future of genre (analysis) in second language

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 30

writing, Tardy (2011, p.1) presents a brief history of this theory. She reports, based on Swales (2009, a memoir), that as a response to needs of his overseas students (in the late 70’s) in England, whose L1 was other than English and expected to get their work published in English, Swales (1981) has proposed his first rhetorical model for introductions of research papers, initiating a landmark for the genre analysis pedagogy2, as known today. Swales (1990) proposes genre analysis as a way to facilitate the teaching and learning of English for Academic Purposes (EAP), especially the writing of research papers (RP), by speakers of other languages. His studies reveal that there are patterns more or less prototypical in the texts and predictable (or desirable) rhetorical choices in each item of a RP. Genre analysis pedagogy has as its main purpose to bring academic language users (writers and or presenters) awareness about rhetorical-organizational (macro-structural) and linguistic (micro-structural) textual factors regarding each specific discursive genre. The main focus of this paper is the micro-structure factor, because our practice as a teacher and teacher educator for years has revealed, and data discussed in the analysis session of this work demonstrates, that grammatical aspects/ language choices are a first challenge when writing in a FL (our working context). Swales and Feak have developed a series of teaching materials (2009, 2011 and 2012). The authors propose a pedagogical work focused on abstracts in one of their 2009 book series. In this volume, the authors focus on abstracts for: research articles, short communications, conferences, and Ph.D. dissertations. Besides offering accounts for rhetorical moves, they also provide some focus on appropriate language choices to meet specific meaning challenges in the writing of different abstracts. They show, for example, that there are basically four kinds of introductory sentences to RA abstracts (Swales and Feak, 2009, p.10), as follows:

Type A: Economists have long been interested in the relationship between corporate taxation and corporate strategy. Type B: The aim of this study is to examine the effects of the recent change in corporate taxation. Type C: We analyze the corporate taxation return before and after the introduction of the new tax rules.

2 Swales’ genre analysis pedagogy has originated from ESP (English for Specific Purposes). For further understanding on genre

analysis historical development see: Hyon, S. (1996). Genre in three traditions: Implications for ESL. TESOL Quarterly, 30, 693–

722.

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 31

Type D: The relationship between corporate taxation and corporate strategy remain unclear.

In terms of meaning, each of these different choices will determine which kind of information and/or action the author intends to stress. Furthermore, for each case there are appropriate language choices. This fact is not necessarily transparent to language users (many times L2/FL learners) and to express meaning the way they do want to, writers should be aware of their possible choices in terms of both, macro and micro language choices. Hyland (2007, p. 150) also discusses the potential of genre analysis in the teaching and learning of writing and asserts that:

The introduction of genre pedagogies is also a response to the still widespread emphasis on a planning-writing-reviewing framework which focuses learners on strategies for writing rather than on the linguistic resources they need to express themselves effectively.

The challenges of writing, especially in a language other than L1, are many and far too complex to being accomplished using any single method or pedagogical practice. Process writing (Zamel, 1982) has certainly offered a rich contribution by supporting studies about how language learners get and develop ideas when they first start to develop the skill of writing in a L2/FL. Albeit helpful, this kind of practice is not enough to enable academic writing. By being taught to reflect about the rhetoric organization and the possible linguistic choices in regard to their respective meaning, language learners will be offered possibilities to have more autonomy in deciding how they want to present and represent their ideas. This is not a curative prescription, but certainly an additional perspective for generating more choices in the learning and teaching of writing.

3. Focused Attention

The role of explicit language (especially grammar) teaching has been largely debated in the last twenty years. The central question continues to be whether a second or foreign language can and should be acquired only by exposition and interaction, similarly to what happens with L1, as

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 32

defended by Krashen (1985) and researchers that support his theory or if focused attention has an important role to play in the process, as reasoned by Schmidt and Frota (1986), Schmidt (1990), and many other studies recently developed after these two milestone publications about awareness and language learning. This question is important in the area of language teaching and learning because it has direct pedagogical implications. Schmidt (1995) argues that doing something incidentally is different from doing it unconsciously. He recognizes that consciousness is hard to measure, and even to define (Schmidt, 1995, p.5), but defends that the importance of the question for the area of language teaching justifies the efforts of further studies about this question. Although the question of “if, when and how” to focus on language form (s) when teaching L2/FL remains controversial, a number of recent studies have reported concern about the role of grammar in foreign or second language classes. Nassaji and Fotos (2004), for instance, remind us that debates about the role of grammar teaching in language teaching have been carried for 2000 years. The adoption of different teaching methods has contributed to heterogeneous definitions of grammar, as well as posed some difficulties in deciding if, and how, form-focused instruction should be part of the curriculum. Spada and Lightbown (2008) explain that those adopting a strong communicative approach interface prefer to disregard a role for grammar instruction in L2/FL classes. The (rich) input hypothesis (Krashen, 1985) has certainly contributed to favor advances in the communicative approach, but has also opened avenues of doubt about possible benefits brought by focus on language form(s). Krashen’s assertion that what is learned consciously does not become ready to access in spontaneous use has contributed to a practice in which many professionals involved with language teaching and learning disregard any role for grammar in ESL/EFL curricula. On the other hand, Batstone and Ellis (2009, p.195) advocate that “effective grammar instruction must complement the processes of L2 acquisition”. Batstone (1994) states that there is a critical gap between product (structure focused) and process (communication focused) teaching perspectives. In his view, the first does not provide opportunities for proceduralization (automatic language use) and the latter leaves room for inadequacies in language use. For the author, combining product and process teaching is desirable with the care of avoiding doing everything for the learner in the product phase and providing opportunities for learners not only participating actively, but activating grammar in the process phase. That is exactly the idea of his proposal for teaching grammar as skill, integrating focus on meaning with attention to form. Nonetheless, as reasoned by

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 33

Larsen-Freeman (2003), the essence of the question relies on what is meant by grammar, that is, what concept of grammar one is considering when discussing a place for grammar(ing) instruction. She defines grammar as “one of the dynamic linguistic processes of pattern formation in language, which can be used by humans for making meaning in context-appropriate ways” (p. 142). The author also proposes a three-dimensional view of grammar, showing that grammar has to do with form (syntax), meaning (semantics) and use (pragmatics). As stated by Nassaji and Fotos (2011, p. 5), traditional grammar-based approaches departed from the idea that “language consists of a series of grammatical forms and structures that can be acquired successively”. This view and its consequent deductive and linear practice of grammar structures has long proved inadequate in providing language learners with the tools they need to communicate, precisely because communication involves many more features, which are far more complex than memorizing grammar rules. Albeit grammar is not only related to form (structure), the traditional view that studying grammar means studying and practicing discrete rules still prevail in the mind of many professionals involved with language learning and teaching. This fact brings two consequences, both problematic to our view: 1) many still stick to this sequential discrete practice, and 2) a great deal have prejudice about a role for grammar in their practice and are closed to more update views of grammar and its teaching. In her book Teaching Language: From Grammar to Grammaring, Larsen-Freeman (2003) proposes that grammar should be seen as a skill. Grammaring is a term coined by her to refer both to the (synchronic and diachronic) dynamism of language and also to defend the point of view that grammaring is the ability to deploy grammar accurately, meaningfully and appropriately in discourse level (our emphasis), and this ability might be regard, according to the author of the term, as a fifth skill. Taking discourse level language use into consideration, combining genre analysis, especially focusing on linguistic choices that are appropriate or more common in each genre, and a grammar(ing) pedagogy can create rich language teaching and learning experiences. Both theories rely on awareness raising to help language learners to understand reasons behind language choices. In a recent paper about the future of genre analysis, Swales (2011, p. 83) states that certain “grammatical elements have useful rhetorical roles to play in the construction and deconstruction of academic discourse”. Besides that, he also recognizes that metalinguistic terminology is important in the development of “useful and applicable genre-analytic skills in graduate-student writers”.

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 34

Although we are aware of the importance of avoiding prescription and imposition in any social segment, it is our understanding that pattern seeking is different from patter imposing. It is important to be well familiar with patterns to get started in a(n academic) discursive community, so that one can have his/her voice heard, even when aiming at criticizing impositions. As discussed by Larsen-Freeman and Anderson (2011, p. 168):

Learning the unique forms, vocabulary, and norms of different discourses is empowering. Teachers who embrace this idea will find themselves examining their teaching practice, choice of texts, activities, and assessment tools, looking for when and how power is explicitly or implicitly expressed. In addition, they may decide to work with students on a sample of language, looking at the author’s word choices, what grammar structures are used, and other aspects of language use. This activity might increase students’ ability to make vocabulary and grammar choices within the range available to them.

It is important to recognize that the lack of tradition in integrating focus on form and communication, and the need of further classroom applied investigation, as proposed by Svalberg (2012), reveals a shortage of available practical teaching possibilities.

Batstone and Ellis (2009) present some illustrative examples of pedagogical practice that maintain a primary focus on meaning, but consider attention to form. The authors defend that there should be three principles supporting this kind of practice: 1) the given-to-new (departing from what learners already know to facilitate the building of new relations between form and meaning); 2) the awareness raising (asserting the importance of consciousness in language learning), and 3) The real-operating conditions (necessity to grant learners’ opportunities to experiment the target language similarly to the ways it operates outside the classroom). Ellis (2010, p. 198) writes in the conclusion of his paper on second language acquisition (SLA), teacher education and language pedagogy: “the purpose of an applied SLA researcher is not to assume the relevance of SLA to language pedagogy but rather to enquire into its applicability”. Consequently, those of us involved with the multiplicity roles of being second/foreign language acquisition classroom researchers, teachers and teacher educators; need to make our studies, practices and reflections available, so that such applicability can be considered.

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 35

4. The study: context and methodology

This exploratory study consisted of analyzing how prospective EFL teachers (participants, hereafter) would react to a pedagogical practice which combines two theories aiming at learners’ awareness raising to improve their writing skills in the target language (English). In the class where data was collected there were 16 participants, whose age ranged from 19 to 24. The context of data collection is a 60 hour-long course on EFL writing at an undergraduate teacher education program in a public university in Brazil. The discipline is offered in the third year (of a 5-year-long program) and it aims, simultaneously, at improving participants’ (Portuguese speakers) writing in the target-language and preparing them to reflect about important aspects in the teaching-learning of (EFL) writing. The syllabus has been designed to reach the dual goal and especial attention has been given to awareness raising. Having that agenda in mind, the theories that support our practice in the course are those of genre analysis and focused attention to form (in the sense of informed language choices: grammaring) especially because, as previously discussed, both theories rely on awareness raising. Regarding genre analysis, in the beginning of the course we identify, together with the participants, by eliciting their impression upon text analysis, three main pillars to determine a genre: form, communicative purpose(s) and target-audience. As for grammaring, we guide the participants to analyze what are the possible language choices in each genre studied and discuss why. The principle underlying this choice is that, as asserted by Larsen-Freeman (2003, p. 21) the central role of a teacher should be to teach students to learn, by cultivating in them an attitude of inquiry. To reach our goals, the teaching activities are diverse, departing from genres that the participants are more familiar with and increasing the challenge as the course develops, arriving at abstracts as a sample of the academic genre. The selected genres are: advertisements, fables, fairy tales, comic strips, summaries, conference abstracts and journal abstracts. There are three main reasons for selecting these genres: 1) they range from more to less familiar to the participants (contributing to move from known to new); 2) some grammar features are predictably salient in respect to each of these specific genres (likely to facilitate awareness), and 3) the possibility to preview/review important language features and choices in regard to the purpose(s) and target-audience of the text (discourse level analysis). For example, advertisements for children are different from those

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 36

for adults; a summary to “sell” a book is different from one to reveal understanding of main points, and so on. All the activities aim at raising participants’ awareness about linguistic factors and count on their participation to draw conclusions, so that they are engaged with the language and also with their learning. The sequence of the activities proposed at the course can be summarized as follows: • discussing the characteristics of (less prototypical)advertisements; • reading and telling fables and fairy tales, transforming a fable into comic

strips; • reflecting about changes in form though genre transformation; • reflecting about what characterizes a summary; • reading and discussing a theoretical text about genre analysis: Hyland

(2007); • developing a pedagogical unit (PU), supported by a theory of each

participant’s choice (reading a theoretical text whose original abstract has been removed);

• studying characteristics of journal abstracts based on Swales and Feak (2009);

• writing an abstract for the theoretical text each one had read for developing his/her PU and comparing it to the original abstract of the text;

• studying characteristics of conference abstracts; • writing an abstract to submit the presentation of their PU in a conference.

Data has been collected in three different ways: 1) A blog3 was created to collect participants’ impressions about the proposed pedagogical practice and development. Some of their comments are analyzed, because these reveal their gradual comprehension and reactions to the pedagogical proposes; 2) micro-structural features from participants’ texts written in the genres studied are analyzed and discussed, as they show practical outcomes, and 3) upon conclusion of the course the participants have been asked to answer a brief questionnaire (5 questions)4 about what they had learned in the course, their comments serve to evaluate their final view of the process.

3 Blog address: gaelmatew2012.blogspot.com 4 The questions were: 1) What do you think you have learnt in this course? 2) Do you think you have learnt grammar? Please justify your answer. 3) Can you establish any relations between textual genres and linguistic choices? If affirmative, which ones? Why? 4) What have you learnt about academic texts? And specifically about abstracts? 5) Please add any comments or suggestions that you like.

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 37

The data analysis, qualitatively discussed in the section 5 of this paper (practice and results), show how each of these instruments help us to understand which aspects from the discussed pedagogical practice has worked well, what needs to be redesigned, and why.

5. Practice and results

The results from the pedagogical practice reported here will be presented in the order that they occurred in the course. Participants’ texts and comments are presented and commented along the analysis.

5.1. Advertisements

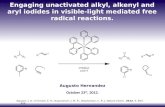

We have decided to work with advertisements, because they are highly rich samples to raise awareness about the importance of the communicative purpose(s) and target-audience in the form of a given genre. Peculiar ads have been selected (see Figure 1) to make participants aware that even when a genre resembles something else, its communicative purpose (s) will help us to classify it appropriately. It also shows that there is room for more or less flexibility in what is expected from texts belonging to a given genre, depending on its purpose and audience.

5.2. Fables and fairy tales

We have chosen to work with fables and fairy tales, because of several reasons: 1) they are popular genres, known by everyone; 2) most people cannot tell promptly the difference of these genres, and an analysis would be helpful in enriching awareness raising by participants; 3) there are some grammatical features that may seem a little problematic for language learners, such as reported versus direct speech, past perfect and the future in the past, all which can be analyzed at discourse level within these genres, and 4) as participants are preparing to be EFL teachers, they may use texts from these genres in their future classes. After telling, reading and enjoying firstly fables, and later fairy tales, participants were asked to analyze their structure, comparing them to each other, thinking of language choices, purposes and target-audience. Only after

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 38

this activity participants revealed being aware of the fact that fables and fairy tales may seem alike, but that there are elements in the 3 basic pillars of genre, one being form (language choices), that make each of them distinct genres. Upon a first question about which were the characteristics of these genres, most participants were confused about their difference.

Figure 1: Activity with ad to support awareness about genre characteristics.

5.3. Genre transformation

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 39

The aim of this practice was to have participants manipulate language and reflecting about necessary changes when similar ideas are presented in different genres. Participants chose a fable of their preference and transformed it into comic strips to present to their colleagues and discuss necessary changes from one genre to the other. Some of the participants, simply added pictures to the original (fable) text and made some verb tense changes in the dialogues Others, besides these, also changed lexical items (see Figure 2). Two of them, have changed the plot, keeping the same idea and moral of the source texts, but bringing more up-to-date subjects in the plot (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: Genre transformation – fable to comics – example 1

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 40

Figure 3: Genre transformation – fable to comics – example 2

Svalberg (2012) discusses the importance of language awareness (which she calls LA) in developing engagement with the language (EWL) through consciousness raising tasks. In her words:

It is important to understand why learners engage, or why they do not. Task design can be expected to play an important role. An LA approach to language learning/teaching is likely to make use of what has been called CONSCIOUSNESS RAISING (CR) tasks. The purpose of a CR task is that the learner should ‘arrive at an explicit understanding of some linguistic property or properties of the target language’ by carrying out a task on some L2 data (Ellis, 1997: 160). In other words, CR is one way of generating EWL (Pages 377-378) (emphasis added).

Based on the results of our study, we defend that genre transformation activities, such as the one illustrated here, have a rich potential in getting students engaged with the language, and consequently more aware of appropriate linguistic choices in accordance with each textual

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 41

genre. While the idea is simple, we would also argue that it is far from common to find available teaching materials with this characteristic. Regarding CR (consciousness raising) through EWL (engagement with the language), one of our participants wrote in her answer to question 3 in the final of the term questionnaire:

Of course, considering different genres, for example, comic strips and tales, linguistic choices are specific acording to text. I could realize it better by the activity in transforming a fable to a comic strip.5 (Georgia)

Awareness is not enough, students will need practice and repeated opportunities to reflect about the quality of their own language production, as defended by many researchers in the area of language learning, including Batstone (1994) and Larsen-Freeman (2003). However we believe that awareness is a first and key condition for intake, as also defended by these and other applied linguistics, especially after Schmidt (1990).

5.4. Summary

Summary writing is an important practice in the academic life and surprisingly, every year when trying to elicit what our undergraduate students know about its characteristics, we have realized that most do not know the main characteristics of a summary. It has not been different in this exploratory study, most participants said in class that they had written a few summaries in high school, but also recognized that they had never been really taught how to do or analyze it and revealed uncertainty about how it should be organized. Participants were assigned the reading and summarizing of “Cinderella”, the literary version by the Grimm brothers, and later they should compare their summary to a provided model . This activity was designed to possibility awareness that only what is in the original text can be used in a summary (students know different versions of Cinderella and often wrote things from their minds). We also aimed at offering different language choice possibilities in summary writing, by discussing, for example the

5 The participants’ texts will be maintained in their original form, without editing of language mistakes (or errors). Also nicknames will be used instead of the real name of the participants.

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 42

differences between a summary written to present understanding of main points and one written to promote a book selling, for instance. Participants reported their awareness of these facts in the blog (gaelmatew). Some of the comments were:

I noticed that my summary is very poor in details. If it was a generic summary about Cinderela's plot or something like that, it would be ok. But since it was asked to us to do a summary from Grimms version, I think that mine does not fit very well. There were also some language structure and vocabulary that didn't fit quite well in the genre. (Nadia) I've also noticed that the text was narrated as if the reader had a previous knowledge of the narration, thus missing the goal of presenting the reader with a complete and intelligible summary of the work in question. (Samantha) I understand also that a summary depends of the purpose, for example, the using of the verbs tenses. It is common that fairy tales are narrated in the past tense, but as we saw in class, fairy tales can be narrated in the present tense also, it depends on who tells, what is the purpose etc. However, I think I can change my summary on some points, for example, do not put unnecessary information or implied, to attention to the use of appropriate terms (ex: ladies, instead of "girls" in this case). (Andy)

As participants’ comments show, if educated to analyze their own production in regard to others, they can notice the necessity of changes on their own. This is part of educating for awareness (awareness raising) and a key element in the teaching of genre analysis and grammar(ing) . About the importance of this kind of outcome in language learning, Svalberg (2012, p. 378) cites Eckerth:

Referring to Sharwood Smith (1981), Eckerth (2008: 12) explains: Rather than L2 explicit knowledge per se, it is the potential effect of such knowledge on input perception, language processing, and output monitoring which can be conducive to second language acquisition, an effect which has been referred to as CONSCIOUSNESS RAISING. (original emphasis)

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 43

It is also interesting to notice that some participants have chosen to write their summaries either in the present or using direct speech for the dialogues, as ways to avoid language structures that they were not comfortable with. It reveals that they were able to make informed language choices to have a better performance in their text writing, as seen in the following examples:

Two stepsisters go, but the stepmother doesn’t allow Cinderella to join. However, some friends help her and then she goes in secret. In the party (...). (David’s summary) The next day the prince went to reach the owner of the shoe, for he had said: “I will marry the owner”. When he got at Cinderella’s house, the stepsisters went down to try on the slipper, but their feet did not fit the shoe even after cutting heels and toes(...). (Nadia’s summary)

Based on comments presented by the participants and on the summaries that they have (re)written, it is possible to indentify how much more sensitive to linguistic choices in regard to the genre they became after performing the proposed activity.

5.5. Reading and discussing a theoretical text about genre analysis and its pedagogical implications

Participants were also assigned to read the text Genre pedagogy: Language, literacy and L2 writing instruction by Hyland (2007). They were asked to write the main points of the text and there was a discussion about them in class. The idea was to provide participants with a view of pedagogical implications of genre analysis, which can serve them both, as language learners and as prospective teachers. The rationale for that is our evaluation that they should know why they were being introduced to genre analysis. Understanding the reasons for practices is important, especially for prospective teachers and they performed relevant discussions from this opportunity.

5.6. Developing a pedagogical unit (PU)

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 44

In the discipline where data has been collected, prospective teachers are required to design a pedagogical unit. Besides being one more opportunity to practice writing, it helps make participants aware that there should be principles to design/adapt teaching activities. They choose the audience and topic, but have to read a theoretical text in applied linguistics, in accordance to the topic in their PU, to provide them with some foundation for their work. For this study, the abstract was removed from the original theoretical text, so that participants could write an abstract for it after studying characteristics of journal abstracts. They later had to compare the abstract that they had written to the theoretical text with the original one, as described in 4.8. Svalberg (2012, p 384) cites Andrews and McNeill (2005, p. 159) in their discussion about how important it is to have teachers engaged in reflecting about language choices:

We have become increasingly convinced that the extent and the adequacy of language teachers’ engagement with language content in their professional practice is a crucial variable in determining the quality and effectiveness of any L2 teacher’s practice.

Designing a pedagogical unit has been highly engaging for the participants, according to their comments at our blog, we can illustrate that with the following comment:

During the process of preparing our teaching unit, I tried my best to do something applicable and something fun. As future teacher and also students, I believe that we have to prepare something that we would like to be given to us in the classroom, so, due to this, a dynamics class, connecting not only the four English skills but also the students’ progress and production is always the best way to start. Something that Gary, Georgia and Samantha and others have already said and I totally agree with them, is that having a foundation text to guide us or even to clear up some ideas to us, is very important and now that we know what some specific vocabulary means (such as EFL, ESP – I never thought that ESP is so, so funny to work it and so applicable and effective!! –,etc) we are able to found it ourselves, not giving the excuse that the teacher (during our undergrad course) didn’t help us.(Guido, blog).

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 45

Guido comments on how good it was to receive some theoretical support to design his PU, quotes similar impressions from three other colleagues and reveal engaged with the task, by describing how much reflection he made to accomplish it.

5.7. Studying characteristics of journal abstracts based on Swales and Feak (2009)

After studying Swales and Feak’s (2009) chapter on journal abstracts, participants had to read six abstracts from papers in Applied Linguistics and classify, mainly linguist information, based on the possibilities presented on a table containing features raised by Swales and Feak (see Figure 6)

Figure 6: Summarizing characteristics of abstracts (table designed based on Swales and Feak’s 2009 list of important characteristics from abstracts)

The idea was to give participants a chance to analyze an academic genre. Abstracts seem to be appropriate, because they represent the extract of a full paper, providing a flavor of research goals, methods and results. Also abstracts are short and not too demanding for learners, in spite of being challenging.

Participants were amazed by realizing the different choices that authors can make when writing their abstracts. Some commented in class that they had never thought of the implication of choices in certain meanings. For example, verb tenses: if a writer uses the past to report an idea he may agree with it less than if he cites it in the present, and so on.

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 46

In the end of the term questionnaire, almost two months after having studied the characteristics of abstracts, 9 out of the 14 participants who answered it, mentioned important characteristics of academic texts and their importance, as follows:

I have learned that academic texts have specific characteristics, such as time, aspect, voice, sentence order and technical words that make academic texts more scientific and reliable. I have also learned that it is very important to read them! (Gary – question 4). I learned a lot about this textual genre. Even in portuguese, I have never had contact with this genre, so it was important the writing of this texts. Now I can even transport what I have learned in English, to the portuguese language, when I will write an article. For those who want to make their career on this area (english studies) I think it’s even better, because now we already know about this genre and its elements. Elements such as: research topic, number of sentences, number of words, main verb tense, voice and person, reference to previous studies and metadiscoursal expressions were shown for us and its importance in the construction of program book abstracts and article abstracts. (Emily, question 4)

It is possible to notice that participants are learning more than the target language in this case, they are also learning the importance of academic texts more generally speaking.

5.8. Writing a paper abstract

Participants were asked to write an abstract for the theoretical text each one had read for developing his/her PU, and to compare it to the original abstract of the text. This activity aimed at creating an opportunity for noticing if they had made similar or different language choices when writing an abstract and why. Participants point that they have realized what were some of their problems and they enjoyed the opportunity.

Oh, it's a fact! Certainly I will write more accordingly. Since we are aware of our mistakes and errors in a text, our mind recaps a great number of situations in which we have needed to produce a text and we try don't

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 47

commit these problems again in another opportunity. This way comparisons, analyses and feedbacks are extremely relevant in the building process of the writing competence in a foreign language. (David, blog) As Nadia and David said, noticing our own mistakes and errors make us better, it’s a kind of progress specially when we rewrite the text after analyzing it. So, the more we practice the best we will be! (Amy, blog)

Although participants had a good performance in terms of grammar structures (regarding verb tenses, for instance), they have not noticed their problems in word order in the sentence. They wrote some sentences in a sequence that resembles Portuguese (L1), as we can observe in the following examples:

This paper discusses how to facilitate the learning of a language based on a syllabus which helps to promote conditions for that. English young learners need an especific method to have a successful leaning, based on conception of the language as communication. (Georgia, journal abstract). The growth of Internet influence has been increasing and its use has become part of the process of teaching and learning a foreign language. This article presents an explanation about how the use of Internet technology nowadays can help the development of materials and syllabus design, through the appointment of many studies about the pedagogical characteristics of this use and its importance on the construction of the knowledge (Piaget, 1932). (Emily, journal abstract) Finally, it talks about the impact of technology on writing pedagogy, arguing about the importance of having instruction on thechnological tools and online resources in order to use them in classroom and provide feedback to the students. (Gary, journal abstract). Many different aspects should be concerned when working on the production of course books. Such aspects must be even deeply considered when thinking about adult course books. (Nadia, journal abstract) The developments that have been achieved are highlighted then according to the skill it is related. (Bill, journal abstract)

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 48

However, interestingly enough, in spite of having some sentence order problems, they have structured their text more appropriately in their journal abstract, when they had a source text to prime their writing, than they did when writing a conference abstract based on the pedagogical unit that they had designed by themselves, as we can observe in 4.10. These results have important implications for the teaching of writing and deserve a detailed study, considering that we cannot perform a comprehensive analysis here due to space limitation.

5.9. Studying conference abstracts characteristics

Similarly to studying journal abstracts (described in 4.7), this time participants read several abstracts from TESOL Conference6 2011 and classified linguist choices based on the model presented in the unit studied in their previous classroom (based on Swales and Feak, 2009)

5.10. Writing a conference abstract

Writing an abstract to be submitted for presentation of their PU at a conference was a practice that aimed to provide participants with the chance to practice a genre that they may need to write in their professional life. As observed in 4.8, participants wrote in a sentence order more similar to L1 in this activity, where they did not have a source text to write an abstract from, but should have their PU as a source. Here are some examples:

Believing that most of our students would have a pet, we thought that talking about “how to take care of your puppy”, as the project is named, would be an opportunity to involve the children in the discussions about it in order to improve the four skils – speaking, listening, reading and writing-, to promote familiarity to English language and to stimulate sense of responsibility, which is important for that age level. (Georgia – conference abstract)

6 It is an important annual conference in the area of teaching English a L2 or FL. TESOL stands for

Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages.

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 49

(…) Integrating the use of four skills (writing, orally, listening and reading) and visual literacy, the exercises were prepared in order to call the students attention to the importance of being aware about the structure of this new genre and have already in mind the simple elements of the narrative genre (characters, time, set, plot). (Emily – conference abstract).

Classes are build up with the objective of incentive students to work with several aspects of the language in order to produce and share their own fan-fictions. (Gary – conference abstract)

We chose here to work with screenplays and comic books as an example making them aware “of the language used there”. (Nadia – conference abstract) This article presents the use of an internet-based recent-born genre, the memes, as a useful resource to help students to understand better the concept of genre and its branches and also as a credible way to stimulate and improve their production. (Bill – conference abstract).

As it can be seen from these examples, participants rely on the structure of Portuguese (L1) to organize the sentence order. In future offers of the course it should be taken into consideration and preemptive noticing activities should be designed, focusing sentence order analysis. Naturally after this intervention, we should analyze the results. It is also curious that although participants had freedom to choose any themes or linguistic questions that they wished in the design of their PU, most of them decided to have some focus on the relations between the genres they would work with and linguistic choices.

6. Conclusions

In this paper we have discussed how prospective EFL teachers in Brazil reacted to being instructed through the combination of genre analysis and focused attention (grammaring) in a discipline on writing. The aim was to contribute with reflections about pedagogical practices in the teaching-learning of the skill of writing in EFL. Results show that the integration of the discussed theories has favorable outcomes in participants’ awareness regarding language choice possibilities in the genres that they studied. The

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 50

exploratory study reported here has also indicated the necessity of similar analysis with different foci, as the case of the sentence order (briefly discussed in 5.8 and 5.10). We would also argue that the practice described in this work has an important contribution in proposing a reflection about ways to reach a dual challenge in EFL teacher education programs: to teach the target-language and to educate the prospective teacher to be an informed professional at the same time. We recognize that this study is limited in showing participants’ language improvement (further studies are necessary with more focused work), but at the same time it certainly shows that the integration of genre analysis and grammar(ing) has a high potential in favoring learners’ awareness regarding language choices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author acknowledges the financial support received from “Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo” (FAPESP) (Proc. 2012/03944-7). The author also fully appreciates Professor Diane Larsen-Freeman (University of Michigan) for having received her during her sabbatical leave, making the development of this study possible and contributing with insightful discussions.

Recebido em julho de 2014 Aceito em agosto de 2014

REFERENCES BATSTONE, R. Grammar. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1994. BATSTONE, R., Ellis, R. Principled grammar teaching. System 37, 2009, P. 194–204 ELLIS, R. Second language acquisition, teacher education and language pedagogy. Language Teaching 43, (2), 2010, P. 182-201. FERREIRA, M. M. Constraints to peer scaffolding. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada 47, (1), 2008, P. 9-29. FREIRE, P. Pedagogia do Oprimido, 17a. Ed., Rio de Janeiro, Paz e Terra, 1987. HYLAND, K. Hedging in Academic Writing and EAP textbooks, English for Specific Purposes 13, (2), 1994, P. 239-256. HYLAND, K. Genre pedagogy: Language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing 16, 2007, P.148-164.

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 51

KRASHEN, S. The Input Hypothesis: Issues and Implications. London, UK: Longman, 1985. LARSEN-FREEMAN, D. Teaching Language: From Grammar to Grammaring. Michigan: Heinle ELT, 2003. LARSEN-FREEMAN, D.; ANDERSON, M. Techniques and Principles in Language Teaching. 3rd. Ed., Oxford University Press, 2011. MOTTA-ROTH, D. O Ensino De Produção Textual Com Base Em Atividades Sociais e Gêneros Textuais. Linguagem em (Dis)curso – LemD 6, (3), 2006, P. 495-517. NASSAJI, H.; FOTOS, S. Teaching Grammar in Second Language Classrooms: Integrating Form-Focused Instruction in Communicative Context. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2011. NASSAJI, H.; FOTOS, S. Current developments in research on the teaching of Grammar. In: Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, Cambridge University Press, nº 24, 2004, p. 125-145. PALTRIDGE, B. Genre Analysis and the Identification of Textual Boundaries. Applied Linguistics 11, (3), 1994, P. 288-299. PALTRIDGE, B. Working with genre: A pragmatic perspective. Journal of Pragmatics 24, 1995, P. 393-406. PALTRIDGE, B. Discourse Analysis: An Introduction. , 2nd. Ed., Hong Kong: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. RAMOS, R. C. G. Gêneros Textuais: Uma Proposta de Aplicação Em Cursos de Inglês Para Fins Específicos. The ESPecialist 25, (2), 2004, 107-129. SCHMIDT, R. W. The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics 11, (2), 1990, P. 129–158. SCHMIDT, R. Consciousness and foreign language learning: A tutorial on attention and awareness in learning. In: Schmidt, R. (org.), Attention and awareness in foreign language learning, Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii, National Foreign Language Resource Center, 1995, pp. 1-63. Schmidt, R. "Attention." In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction. Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 3-32. SCHMIDT, R.; FROTA, S. Developing basic conversational ability in a second language: A case study of an adult learner of Portuguese. In: DAY, R. R. (org.), Talking to learn: Conversation in second language acquisition. ROWLEY, M. A.: Newbury House, 1986, pp. 237-326. SPADA, N.; LIGHTBOWN, P. M. Form-Focused Instruction: Isolated or Integrated?. In: TESOL Quarterly 42 (2), 2008, pp. 181-207. SVALBERG, A. M. L. Language awareness and language learning. Language Teaching 40, (4), 287-308, pp. 2007 SVALBERG, A. M. L. Language awareness in language learning and teaching: A research agenda. Language Teaching 45, 2012, pp.376-388

Revista Contexturas, n. 21, p. 26 - 52, 2013. ISSN: 0104-7485 52

SWALES, J. M. Aspects of Article Introductions. Aston Research Reports, n.1, Language Studies Unit. The University of Aston at Birmingham, 1981. SWALES, J. M. Developing materials for writing scholarly introductions. In R. R. Jordan (org.) Case Studies in ELT. London: Collins, 1983, pp. 188-200. SWALES, J. M. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings, Cambrigde: Cambridge University Press, 1990. Swales, J.M., 1996. Occluded Genres in the Academy: The case of the submission letter. In E. Ventola and A. Mauranen (eds), Academic Writing: Intercultural and Textual Issues. Amsterdam. John Benjamins, 1996, pp.45-58. SWALES, J. M. Research Genres: Explorations and Applications, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004. SWALES, J. M. Coda: Reflections on the future of genre and L2 writing. Journal of Second Language Writing 20, 2011, pp. 83–85. SWALES, J. M.; FEAK, C.B. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: A Course for Nonnative Speakers of English, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1994. SWALES, J. M ; FEAK, C. B. Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2009. SWALES, J. M ; FEAK, C. B. Creating Contexts. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2011. SWALES, J. M; FEAK, C. B. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Tasks and Skills. 3rd. Ed., Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2012. TARDY, C. M. The history and future of genre in second language writing. Journal of Second Language Writing 20, 2011, pp. 1–5. WOOD, A. International scientific English: The language of research scientists around the world. In: FLOWERDEW, J.; PEACOCK, M. (org.), Research perspectives in English for Academic Purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp.71-83. ZAMEL, V. Writing: The Process of Discovering Meaning TESOL Quarterly 16, (2), 1982, pp. 195-209.