August and 16 October, crash landing. He apparently of the Aces...His final score at the end of the...

Transcript of August and 16 October, crash landing. He apparently of the Aces...His final score at the end of the...

replied, "shoot the SOB if you can!"Then all was silence.

Smith's aircraft was mortallywounded, and he tried to regain thefield. He finally had to make a dead-stick landing six miles from the stripand walk back, watching all thetime for roving Japanese patrols.

Second Lieutenant Charles H.Kendrick was not as fortunate ashis skipper. The Zeros had gottenhim on their first pass, and he triedto guide his stricken fighter to acrash landing. He apparentlylanded close to Henderson, but hisfighter flipped over on its back,killing the young pilot.

Major Smith led a party to thecrash site. They found Kendrick stillin his cockpit. They released andburied him beside his plane. StanNicolay recalled, "1 don't knowhow many we lost that day. We re-ally took a beating." Actually, sixWildcats had been shot down or re-turned with strike damage. Severalothers required major repair.

VMF-224's skipper was also shotdown. Bob Galer bailed out overthe water—his third shootdown inless than three weeks—and was res-cued. He had accounted for twoZeros, however. He recalled:

I was up with six fighters,cruising about at 20,000 or25,000 feet. Suddenly, 18 Zeroscame at us out of the sun, andwe took 'em on. The day wascloudy and after a few min-utes, the only other Marine Icould find was Second Lieu-tenant Dean Hartley. In themelee of first contact, I heardseveral Jap bullets splatteragainst—and through—myship, but none stopped me. Atabout the same moment, Hart-ley and I started to climb intoa group of seven Zeros hover-ing above us. In about fourminutes, I shot down twoZeros and Hartley got a possi-ble. The other four were just

too many and we were bothshot down. Hartley got to afield, but I couldn't make it.The Jap that got me really hadme boresighted. He raked myship from wingtip to wingtip.He blasted the rudder barright from under my foot. Mycockpit was so perforated it's amiracle that I escaped. Theblast drove the rivets from thepedal into my leg. I pancakedinto the water near Florida Is-land. It took me an hour-and-a-half to swim ashore. . . .1 wor-ried not only about the Japsbut about the tide turningagainst me, and sharks.Major Galer struggled ashore

where he encountered four menarmed with machetes and spears.Fortunately, the natives werefriendly and took the bedraggledpilot to their village. After enjoyingwhat hospitality his hosts could

offer, Major Galer rode in a nativecanoe to a Marine camp on a beachfive miles away. He made his wayback to Henderson from there.

Marine Aircraft Group 23 and therest of its squadrons also left the fol-lowing day, having earned a restfrom the intense combat of the lasttwo-and-a-half months. Between 20August and 16 October, thesquadrons of MAG-23 and attachedArmy and Navy squadrons hadshot down 244 Japanese aircraft, in-cluding 111.5 by VMF-223 and 60.5by VMF-224. The score had notcome free, though. Twenty-two pi-lots of the group, as well as 33 avia-tors from other Navy, Marine, andArmy squadrons assigned to theCactus Air Force, had been lost.

John Smith had seen his last en-gagement. He received the Medal ofHonor for his leadership during theGuadalcanal campaign and finishedthe war as the sixth highest on the

Maj John L. Smith, LtCol Richard C. Man grum, and Capt Marion E. Carl pose for photosafter returning to the States. LtCol Man grum commanded an SBD squadron at the heightof the Cactus campaign and was universally admired. He eventually attained the rank oflieutenant general, while Marion Carl retired as a major general after fighting in threewars—World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

Department of Defense photo (USMC) A707812

12

.

A New Crew at Cactus

list of Marine Corps aces, closelyfollowed by his friend and rival,Marion Carl. Much to his initialchagrin, Smith found himself on theWar Bond circuit, and then trainingnew pilots. It was not until twoyears later, in 1944, that LieutenantColonel Smith got a combat assign-ment again. As commanding officerof MAG-32 in Hawaii, he took thegroup to Bougainville and thePhilippines.

Marion Carl assumed commandof his old squadron, VMF-223, inthe United States in January 1943and took the newly renamed Bull-dogs to the South Pacific late in thefall. He gained two more kills—aKi.61 Tony (a Japanese Armyfighter) and a Zero, on 23 Decem-ber and 27 December 1943, respec-tively—this time in a Vought F4UCorsair. His final score at the endof the war was 18.5 Japanese air-craft destroyed.

The night of 13-14 October sawthe Japanese pound beleagueredHenderson Field with every gunthey could fire from their assem-bled flotilla offshore, as well as theentrenched artillery positions hid-den in the dense jungle surround-ing the field. The night-long bar-rage might very well have been theend for the Cactus Marines.

The new day revealed that of 39Dauntlesses, only seven could beconsidered operational, only a fewArmy fighters could stagger into theair, and all the TBF Avenger torpedobombers were destroyed or down.The only saving factor was that thefighter strip was relatively un-touched. By the afternoon, a fewWildcats were sent up to mount a pa-trol over Henderson while it pulleditself together. For the next few days,the Cactus Air Force—Marine, Navy,and Army—flew as though its collec-tive life was on the line, which it was.

Although VMF-223 had left,Guadalcanal still had several topscoring aces left, among them Cap-tain Joe Foss of VMF-121 and Lieu-tenant Colonel Harold Bauer ofVMF-212. Throughout October 1942,Foss and Bauer were kept busy byconstant Japanese raids, desperatelytrying to dislodge the determinedMarines from the island.

Lieutenant Colonel Bauer hadled his VMF-212 up from EspirituSanto on the afternoon of 16 Octo-ber, when he finally had his ownsquadron at Henderson. Withempty gas tanks, the 18 Wildcatswere running on fumes as they en-tered the landing pattern in time tosee a U.S. transport under attackfrom Japanese dive-bombers. With-out hesitating, Bauer broke from thepattern and charged into the Vals,shooting down four of them. It wasan incredible way to advertise thearrival of his squadron.

Joe Foss took off on the afternoonof 23 October to intercept an incom-ing force of Betty bombers, escortedby Zeros. Five of the escorting fight-ers dove toward Foss and his flight,followed by 20 more Zeros. Divingto gain speed, the VMF-121 execu-tive officer saw a Wildcat pursuedby a Zero. He fired at the Japanesefighter, shredding it with his six .50-caliber machine guns.

Without losing speed, Foss rackedhis aircraft into a loop behind an-other Zero. He destroyed this secondMitsubishi while both fighters hunginverted over Guadalcanal. As hecame out of the loop, Foss hit a thirdZero. A fourth kill finished off ahighly productive mission.

On 25 October, Foss took offagain against a Japanese raid, andthis time, he shot down two enemyaircraft. Later the same day, Fossgunned down three more Zeros fora total of five in one day, and anoverall score of 16 kills.

Painting by William S. Phillips, courtesy of The Greenwich Workshop

Marion Carl, now a major and commanding his old squadron, VMF-223, made his 17thkill in December 1943, when he shot down a Japanese Tony over Rabaul. Carl was escort-ing Marine PBJ (B-25) bombers in his F4U-1 Corsair when the enemy fighter jumped theraiders. The victory was Carl's next-to-last score.

13

V

Marine Corps AviatorsWho Received

the Medal of Honorin World War II

f the 81 Medals of Honorawarded to Marines for ser-vice during World War II, 11

Marine Corps aviators receivedAmerica's highest military award.Except for two posthumous awards,the medals all went to aces whoserved in the Solomons andBougainville campaigns. The Medalof Honor was awarded to CaptainHenry T. Elrod of \/MF-211 and Cap-tain Richard E. Fleming of VMSB-241. Captain Elrod was killed onWake in December 1941. Althoughhis award is chronologically the firstMedal of Honor to be awarded to a

Marine during the war, his perfor-mance did not become known untilsurvivors of Wake had been repatri-ated after the war.

Captain Fleming was a dive-bomber pilot at Midway in 1942.VMSB-241 flew both the obsoleteVought SB2U Vindicator and theSBD Dauntless during this pivotalbattle. On 5 June 1942, CaptainFleming was last seen diving on aJapanese ship amidst a wall of flak.HIs Vindicator struck the cruiser'saft turret.

Two of the remaining nineawards were for specific actions; the

other seven were for periods of con-tinued service or more than onemission. Seven of these awards werefor service in the Solomons-Guadal-canal Campaign. The awards forspecific actions went to First Lieu-tenant Jefferson DeBlanc (31 January1943) and First Lieutenant JamesE. Swett (7 April 1943).

Five of these awards were origi-nally posthumous. However, MajorGregory Boyington made a sur-prise return from captivity as aprisoner of war to receivehis award in person from PresidentHarry S. Truman.

The Pilots and Their Aircraft

*Lieutenant Colonel Harold W. Bauer, VMF-212. Forservice from May to November 1942. Grumman F4F-4Wildcat.

Major Gregory Boyington, VMF-214. For service fromSeptember 1943 to January 1944 in the CentralSolomons. Vought F4U-1 /F4U-1A Corsair.

First Lieutenant Jefferson J. DeBlanc, VMF-112. For ac-tion on 31 January 1943. Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat.

*Captain Henry T. Elrod, VMF-211. For action on WakeIsland 8-23 December 1941. Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat.

*Captain Richard E. Fleming, VMSB-241. For action atthe Battle of Midway, 4-5 June 1942. Vought SB2U-3Vindicator.Captain Joseph J. Foss, VMF-121. For service in theGuadalcanal Campaign, October 1942-January 1943.Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat.

Major Robert E. Galer, \TMF-224. For service in theGuadalcanal Campaign, August-September 1942.Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat.

*First Lieutenant Robert M. Hanson, VMF-215. For ac-tion in the Central Solomons, November 1943 and Jan-uary 1944. Vought F4U-1 Corsair.

Major Robert L. Smith, VMF-223. For service in theGuadalcanal Campaign, August-September 1942.Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat.

First Lieutenant James E. Swett, VMF-221. For action on7 April 1943 over Guadalcanal. Grumman F4F-4Wildcat.

First Lieutenant Kenneth A. Walsh, VMF-124. For actionon 15 and 30 August 1943. Vought F4U-1 Corsair.

* indicates a posthumous award

14

Lieutenant Colonel Bauer wasadding to his score, too. A veteranaviator, Colonel Bauer was a re-spected flight leader. He frequentlygave pep talks to his younger pilots,earning the affectionate nicknameof "Coach." Bauer had taken overas commander of fighters onGuadalcanal on 23 October.

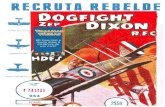

Before the big mission on 23 Oc-tober, the Coach had told his pilots,"When you see Zeros, dogfight'em!" His instructions went againstthe warnings that most of Americanfighter pilots had been given aboutthe lithe little Japanese fighter. JoeFoss' success on this day seemed tovindicate Bauer, however. TwentyZeros and two Bettys, including thefour Zeros claimed by Foss, wentdown in front of Marine Wildcats.

Up to this time the Zero was con-sidered the best fighter in the Pa-cific. This belief stemmed from thefact that the Zero had spectacularcharacteristics of performance inboth maneuverability, rate of climb,and radius of action, all first notedat the Battles of the Coral Sea andMidway. And it was because of itsperformances in these actions that itachieved the seeming invincibilitythat it did. At the same time, theZero was highly flammable becauseit lacked armor plate in any form inits design and also because it hadno self-sealing fuel tanks, such asexisted in U.S. aircraft. Initially inthe war, in the hands of a goodpilot, the Zero could usually takecare of itself against its heavier andtougher American opponents, butearly in the air battles over Guadal-canal, its days of supremacy be-came numbered. By the end of thewar in the Pacific, the kill ratio ofU.S. planes over Japanese aircraftwent from approximately 2.5:1 tobetter than 10:1.

What made the difference as faras Lieutenant Colonel Bauer wasconcerned was his feeling that, inthe 10 months of intense combat

after Pearl Harbor, including theirdisastrous and failed adventure atMidway, the Japanese had lostmany of their most experienced pi-lots, and their replacements wereneither so good nor experienced.Many of the major aces of the Zerosquadrons—the ones who had accu-mulated many combat hours overChina—had, indeed, been lost orbeen rotated out of the combat zone.Whatever the situation, most of theMarine pilots in this early part ofthe war in the South Pacific wouldstill admit that the Japanese re-mained a force to be reckoned with.

The Japanese endeavored to re-assert their dominance on 25 Octo-ber. In a last-ditch effort to removeAmerican carriers from the SouthPacific, a fleet including three air-craft carriers sortied to find theU.S. carriers Enterprise and Hornet,all that remained at the moment ofthe meager U.S. carrier strength inthe Pacific.

The Japanese fleet was discov-ered during an intensive search byPBY flying boats, and the battle wasjoined early in the morning of 26

October. What became known asthe Battle of Santa Cruz occurredsome 300 miles southeast ofGuadalcanal. Indeed, most of theMarine and Navy flight crews at-tempting to blunt remaining enemyair raids still plaguing the positionsof the embattled ground forces onGuadalcanal had no idea that an-other desperate fight was beingwaged that would have a distinctimpact on their situation back atHenderson.

Many American Navy flightcrews received their baptism of fireduring Santa Cruz. Hornet was hitby Japanese dive-bombers andeventually abandoned—one of thefew times that a still-floating Ameri-can ship had been left to the enemy,even though she was burning fromstem to stern. (The carrier was onlya year old.) Enterprise was hit by Valdive-bombers, and the aircraft ofher Air Group 10 were ultimatelyforced to land on Guadalcanal. Thedisplaced Navy crews remained atHenderson until 10 November,while their ship underwent repairsat Noumea, New Caledonia.

While the Marines on Guadalcanal fought for their lives, their Navy compatriots far offshorealso challenged the Japanese. At the Battle of Santa Cruz, October1942, Japanese bombershit the American ships, damaging the vital carrier Enterprise as well as attacking squadronsof inexperienced Navy aircrews. This A6M2 Model 21 Zero launches from the carrierSholalu during Santa Cruz while deck crewmen cheer on the pilot, Lt Hideki Shingo.

Author's Collection

15

-- - ;41•

g:..-

: .4.

•—-.——.,•—:-

While blame and recriminationswent the rounds of the Navy's Pacific commands-for it seemed thatSanta Cruz was a debacle, a strategic and tactical defeat for the hardpressed carrier force-the effects ofthe battle would become clear soon.

Sixty-nine Japanese aircraft hadbeen shot down by Navy F4Fs andantiaircraft fire. An additional 23were forced to ditch because ofcrippling battle damage.

Like Midway, Santa Cruz deprived the Japanese of many of

their vital aircraft and their experienced flight crews and flight commanders. Thus, as the frantic monthof October gave way to November,and although they did not know itat the time, the Cactus Air Forcecrews had been given a respite, and

Brigadier General Roy S. Geiger, USMC

General Geiger, commander of the 1st MarineAircraft Wing, arrived on Guadalcanal on 3September 1942 to assume command of air

operations emanating from Henderson Field. He was57 years old, and he had been a Marine for 35 ofthose years, commanded a squadron in France inWorld War I, served a number of tours fighting thebandits in Central America, and had served in thePhilippines and China. He was designated a navalaviator in June 1917, thus becoming the fifth flyer inthe Marine Corps and the 49th in the naval service. Inthe course of his career, he had a number of assignments to staff and command billets as well as tours atsenior military courses such as the ones at the ArmyCommand and Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, theArmy War College at Carlisle, and the Navy War College at Newport. He also was both a student and instructor at various times at the Marine Corps Schools,Quantico, Virginia. Among other reasons, it was because of his sound training in strategy and tactics atthese schools and his long experience as a Marinethat he was so well equipped to assume command ofI Marine Amphibious Corps (later III Amphibious

Corps) for the Bougainville, Guam, Peleliu, and Okinawa operations.

When Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner,Jr., USA, commander of the Tenth Army on Okinawawas killed, and based on General Buckner's stateddecision before the operation, General Geiger tookover command and became the first Marine ever toaccede to command of as large a unit as an army. Hewas then 60, an age when many men in civilian lifelooked forward to retirement.

But it was at Guadalcanal, where his knowledge ofMarine planes and pilots was so important in defeating the myth of Japanese invincibility in the air, thathe first made his mark in the Pacific War. A short,husky, tanned, and white-haired Marine, whose deepblue eyes were piercing and whose reputation hadpreceded him, compelled instant attention, recognition, and dedication on the part of his junior pilots,many of whom had but a few hours of experience inthe planes they were flying. As told in this pamphlet,out of meager beginnings grew the reputation andsuccess in combat of the aces in the Solomons.

-Benis M. Frank

16

ultimately, the key to victory overthe island.

Meanwhile, under the commandof Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, theJapanese decided to make onemore try to land troops and mater-ial on Guadalcanal and to regainthe island and its airstrips. TheAmericans were also bringing newsquadrons and men in to fortifyCactus Base and Henderson Field.MAC-li arrived on 1 November,bringing the SBDs of VMSB-132and the F4Fs of VMF-112. Newlypromoted Brigadier General LouisWoods arrived on 7 November torelieve Brigadier General Roy S.Geiger as commander of the CactusAir Force. Both men were pioneerMarine aviators, and Geiger hadled his squadrons through some ofthe most intense combat to be seenduring the war. But, almost in-evitably, the strain was beginningto show on the tough, 57-year-oldGeiger. He had once taken off in anSBD in full view of his troops anddropped a 1,000-pound bomb on aJapanese position, showing histroops that a former squadron com-mander in France in World War Icould still do it.

As new planes and crews ar-rived at Henderson and the frus-trated Japanese planned their finalattacks, the Cactus Marines foughton. On 7 November, a sighting of aforce of Japanese ships nearFlorida Island scrambled a strikegroup of SBDs and their F4F es-corts. Captain Joe Foss led eightVMF-121 Wildcats, each with 250-pound bombs beneath its wings.The VMSB-132 Dauntlesses carried500-pounders in their centerline-mounted bomb racks.

The heavily laden aircraft tooksome 30 minutes to climb to 12,000feet as their crews searched for theenemy flotilla. As he looked aheadand below, Foss spotted six Japan-ese floatplane Zeros—a modifica-tion of the A6M2 model of the land-

in October 1942.

and carrier-based Zero—crossingfrom right to left, descending. Alert-ing his squadron mates, he droppedhis light bombs and headed towardthe unsuspecting enemy fighters.

In one slashing pass, Foss' Wild-cats shot down five of the six Zeros,Foss' target literally disintegratingunder the weight of his heavy ma-chine gun fire. One of the otherWildcats shot down the survivingZero. All six enemy pilots bailedout of their fighters and seemed tobe out of danger as they floated to-ward the water. As the incredulousMarine pilots watched, however,the six Japanese aviators unlatchedtheir parachute harnesses and fellto their deaths.

Foss called for his fighters toregroup in preparation for a straf-ing run on the enemy warshipsbelow. He spotted a slow float bi-plane—probably a Mitsubishitype used for reconnaissance—and lined up for what he thoughtwould be an easy kill. However,the two-seater was surprisinglymaneuverable, and its pilotchopped the throttle, letting hisrear gunner get a good shot at thesurprised American fighter.

The gunner's aim was good andFoss' Wildcat suffered heavy dam-age before he finally dispatched theaudacious little floatplane. Soon, theVMF-121 executive officer found athird victim, another floatplane, andshot it down. Regrouping with aportion of his group, he flew back toHenderson Field with another badlydamaged Wildcat. However, thetwo cripples were spotted en routeby enemy fighters. The two Ameri-can fighters tried to get to the pro-tection of clouds. Foss succeeded,but his wingman was apparentlyshot down by the enemy flight.

Foss was not out of danger, how-ever, as his engine finally quit, forc-ing him to glide toward the sea,3,500 feet below. He droppedthrough heavy rain, trying to gaugethe best way to put his aircraftdown in the water. He spotted asmall village on the coast of anearby island and wondered if thenatives would turn him over to theJapanese.

He hit the water with enoughforce to slam his canopy shut, mo-mentarily trapping him in the cock-pit as the Wildcat began to sink. In afew seconds which seemed like an

Painting by Ted Wilbur, courtesy of the artist

Using hit-and-run tactics, Capt Joe Foss flames a Japanese Zero over Henderson Field

17

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 97555

Two aces walk with another famous aviator.Charles Lindbergh, right, visited the Pacificcombat areas several times to help Army,Navy, and Marine Corps squadrons get themost from the respective mounts. Here, thepioneer transatlantic flier visits with now-Maj Joe Foss, left, and now-Ma] MarionCarl, center, in May 1944.

eternity he struggled to free himselffrom his seat and the straps of hisparachute, and force the canopyopen again. His aircraft was wellbelow the surface and only after anadrenalin-charged push, was he ableto ram the canopy back and shootfrom his plane. He remembered toinflate his Mae West life preserver,which helped him get to the surfacewhere he lay gasping for air.

After floating for a long time asdarkness fell, Foss was finally res-cued by natives and a missionarypriest from the village he had seenas he dropped toward the water.The rescue came none too soon assharks, which frequented the wa-ters near the island, had begun toappear around the Marine pilot.

A PBY flew up from Hendersonthe next day to collect him and hewas back in action the day after hereturned, On 12 November, hescored three kills, making him thetop American ace of the war, andthe first to reach 20 kills.

The Battle forGuadalcanal

On the night of 12-13 November,American and Japanese naval forcesfought a classic naval battle whichhas been called the First Battle ofGuadalcanal. It was a tactical defeatfor the Americans who lost two rearadmirals killed in action on thebridges of their respective flagships.

The next day, 14 November, theSecond Battle of Guadalcanal pittedaircraft from the carrier Enterpriseand Henderson Field against a largeenemy force trying to run the Slot,the body of water running down theSolomons chain between Guadal-canal and New Georgia. By mid-night, another naval engagementwas underway. This battle turnedout differently for the Japanese, wholost several ships, including 10transports carrying more than 4,000troops and their equipment.

The Navy and Marines from En-terprise and Henderson hammeredthe enemy ships, while the Ameri-cans on the island, in turn, were ha-rassed day and night by well-en-trenched enemy artillery positionsstill on Guadalcanal and the hugeguns of the Japanese battleshipsand cruisers offshore.

During these furious engage-ments, Lieutenant Colonel Bauerhad dutifully stayed on the ground,organizing Cactus air strikes andordering other people into the air.Finally, on the afternoon of 14 No-vember, Colonel Bauer scheduledhimself to lead seven F4Fs fromVMF-121 as escorts for a strike bySBDs and TBFs against the Japanesetransport ships.

Together with Captain Foss andSecond Lieutenant Thomas W."Coot" Furlow, Bauer strafed oneof the transports before turningback for Henderson. Two Zerossneaked up on the Marine fighters,but Bauer turned to meet the

18

threat, shooting down one of theJapanese attackers. The secondZero dragged Foss and Furlowover a Japanese destroyer whichdid its best to take out the Wildcats.By the time they had shaken theZero and returned to the pointwhere they last saw the Coach,they found a large oil slick withColonel Bauer in the middle, wear-ing his yellow Mae West, wavingfuriously at his squadron mates.

Foss quickly flew back to Hen-derson and jumped into a Grum-man Duck, a large amphibian usedas a hack transport and rescue vehi-cle. Precious time was lost as theDuck had to hold for a squadron ofArmy B-26 bombers landing after aflight from New Caledonia; theywere nearly out of gas. Finally, Fossand the Duck's pilot, LieutenantJoseph N. Renner, roared off in thelast light of the day. By the timethey arrived over Bauer's last posi-tion, it was dark and the Coach wasnowhere to be seen.

The next morning a desperatesearch found nothing of Lieu-tenant Colonel Bauer. He wasnever found and was presumed tohave drowned or have been at-tacked by the sharks which were aconstant threat to all aviatorsforced to parachute into the watersaround Guadalcanal during thecampaign.

Bauer's official score of 11 Japan-ese aircraft destroyed (revised listscredit him with 10) did not begin totell the impact the loss the toughveteran had on the young Marineand Navy crews at Henderson. Hewas decorated with a Medal ofHonor posthumously for his flighton 16 October, when he shot downfour Japanese Val dive-bombers,but the high award could also beconsidered as having been given inrecognition of his leadership of hisown squadron, VMF-212, and later,as the commander of the fighters ofthe Cactus Air Force.

I

The loss of the Coach was a hardblow. Another loss, albeit tempo-rary, was that of Joe Foss who be-came severely ill with malaria.(Many of the Cactus Air Force avia-tors, like the ground troops, battledone tropical malady or another dur-ing their combat tours.) Foss flewout to New Caledonia on 19 No-vember with a temperature of 104degrees. He spent the next monthon sick leave, also losing 37 pounds.While in Australia, he met some ofthe Australian pilots who hadflown against Nazi pilots in theDesert War in North Africa. In oneof his conversations with them, hetold the Aussies, "We have a sayingup at Guadalcanal, if you're aloneand you meet a Zero, run like hellbecause you're outnumbered." In

the coming months, they wouldfind out he knew was he was talk-ing about.

Foss returned to Guadalcanal on31 December 1942, and remainedon combat status until 17 February1943, when he was ordered back tothe U.S. By this time, besides endur-ing several return bouts withmalaria, he had shot down anothersix Japanese aircraft for a final totalof 26 aircraft and no balloons, thusbecoming the first American pilotto equal the score of Captain Ed-ward Rickenbacker, the top U.S. acein World War I. In that war, tetheredballoons shot down counted as air-craft splashed. Of the 26 planesRickenbacker was given credit for,four were balloons.

Joe Foss was one of the Cactus

19

Marines who was awarded theMedal of Honor for his cumulativework during their intense cam-paign. Summoned to the WhiteHouse on 18 May 1943, he was dec-orated by President Franklin D.Roosevelt. After his action-packedtour at Guadalcanal, Captain Fosswent on the requisite War Bondtour. Promoted to major, he tookcommand of a new fightersquadron, VMF-115, equipped withF4U-1 Corsairs.

Originally nicknamed "Joe's Jok-ers," in deference to their famousskipper, VMF-115 flew a short com-bat tour from Bougainville duringMay when there was little or noenemy air activity from and aboveRabaul. Major Foss did not add tohis score.

Painting by William S. Phillips, courtesy of The Greenwich Workshop

Capt Foss saves a fellow pilot by shooting down an attacking Zero during an engagement on 23 October 1942.

ye,

S.

set.

Cactus Victory

By Christmas 1942, the Japaneseposition was clearly untenable.Their troops who remained onGuadalcanal were sick and short offood, medicine, and ammunition.There was still plenty of action onthe ground and in the air, but notlike the intense engagements of theprevious fall. On 31 January 1943,First Lieutenant Jefferson J. DeBlancof VIVIF-112 led six Wildcats as es-corts for a strike by Dauntlesses andAvengers. He encountered a strongforce of Zeros near KolombangaraIsland and took his fighters down tomeet the threat before the Japanesecould reach the Marine bombers.

In a wild melee, DeBlanc, who al-ready had three Zeros to his credit,shot down three more before hear-ing a call for help from the bombersnow under attack by floatplaneZeros. DeBlanc and his flightclimbed back to the formation anddispersed the float Zeros.

Soon after the SBDs and TBFsmade their attacks on Japaneseships, DeBlanc discovered two

more Zeros closing from behind. Heengaged and destroyed these twoattackers with his badly damagedWildcat. DeBlanc and a member ofhis flight, Staff Sergeant James A.

Feliton, had to abandon their F4Fsover Kolombangara. A coast-watcher cared for the two Marineaviators until a plane could comefrom Henderson to retrieve them.

A good closeup of a Wildcat's cockpit and the aircraft's captain on Guadalcanal. Al-though this F4F displays 19 Japanese flags, it is doubtful that it flew with these sincesuch a large scoreboard would have attracted unwanted attention from the Japanese.Note the reflector gunsight inside the windscreen.

National Archives Photo 80-G-37929

20

On 31 January 1943, lstLt Jefferson De-Blanc of VMF-112 earned the Medal ofHonor while escorting Marine dive bombersand torpedo-bombers to Vella Gulf. His flightencountered a larger enemy force and duringthe melee, DeBlanc shot down three floatplanes and two Zeros before being forced toabandon his own plane at a very low altitudeover Japanese-held Kolombangara.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 57750

Author's Collection

This front view of an F4F-4 shows an unusual aspect of Grumman's tubby little fighter.

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 310555

lstLt James E. Swett of VMF-221 was in aflight which rose from Guadalcanal to chal-lenge a large group of enemy planes bent ondestroying shipping off the island on 7 April1943. In a 15-minute period, Swett shotdown seven Japanese bombers, a performancewhich earned him the Medal of Honor.

DeBlanc received the Medal ofHonor for his day's work.

The Japanese evacuated Guadal-canal on the night of 7-8 February1943. The campaign had been costlyfor both sides, but in the longerterm, the Japanese were the biglosers. Their myth of invincibility on

the ground in the jungle was shat-tered, as was the myth surroundingthe Zero and the pilots who flew it.The lack of reliable records by bothsides leaves historians with onlywide-ranging estimates of losses.Estimates placed 263 Japanese air-craft lost, while American losseswere put at 118. Ninety-four Ameri-can pilots were also killed in actionduring the campaign.

Post-GucidalcanalOperations,

February-December 1943Even though the main body of

their troops had been evacuated,the Japanese continued to opposeAllied advances by attacking shipsand positions. The enemy mountedthese attacks through June 1943from their huge bases in southernBougainville and from Rabaul onNew Britain.

On 7 April 1943, the enemy senta huge strike against Allied ship-ping around Guadalcanal. TheJapanese force consisted of morethan 100 Zero escorts and perhaps70 bombers, dive bombers, and tor-pedo bombers. It was an incrediblylarge raid, the likes of which had

not been seen in the Solomons forseveral months. But it was also, atbest, a last desperate gamble by theJapanese in the area.

Henderson scrambled over 100fighters—Wildcats, Corsairs, P-38s,P-39s, and P-40s. Among this gag-gle were the F4Fs of VMF-221. FirstLieutenant James E. Swett, leadingone of the squadron's divisions,waded into a formation of Val divebombers. Swett had arrived onGuadalcanal in February and hadparticipated in a few patrols, buthad yet to fire his guns in combat.

As he led his four Wildcats to-ward the Japanese formation, Swettignored the flak from the Americanships below. He targeted two Valsand brought them down. He got athird dive-bomber as a flak shell puta hole in his Wildcat's port wing.

Disengaging, Swett tested hiswounded fighter, and satisfied thathe could still fly and fight with it,he reentered the fight. Spotting fiveVals hightailing it home, he caughtup with the little formation and me-thodically disposed of four of thefixed-gear Vals. The gunner of thefifth bomber, however, hit Swett'sWildcat with a well-aimed burstfrom his light machine gun, putting.30-caliber ammunition into the Ma-rine fighter's engine and cockpitcanopy.

Wounded from the shatteringglass, and with his vision obscuredfrom spouting engine oil, Swettpumped more fire into the Val,killing the gunner. The Japanese air-craft disappeared into a cloud, leav-ing a smoke trail behind. Americansoldiers later found the Val, with itsdead crew. The troops presentedSwett with the radio code from theVal's cockpit. However, the aircraftwas apparently never credited toSwett's account, leaving his officialtotal for the day at seven.

Swett struggled toward Hender-son but over Tulagi harbor, his air-craft's engine quit, leaving him to

A Marine Wildcat dogfights a Zero over Henderson as other F4Fs finish off anotherenemy fighter at low level.

Painting by Robert Taylor, courtesy of The Military Gallery

21

ditch. The Wildcat hit hard, throw-ing its pilot against the prominentgunsight, stunning him and break-ing his nose. Like Joe Foss sixmonths before him, Swett was mo-mentarily trapped as his aircraftsunk, dragging him below the sur-face. He finally broke free andstruggled to the surface where hewas rescued by a small picket boatfrom Gavutu Island. Only one ofthe four fighters of Swett's divisionhad made it back to Henderson.After intelligence confirmed Swett'sincredible one-mission tally, he be-came the sixth Marine Wildcat pilotto receive the Medal of Honor foraction over Guadalcanal.

Swett's engagement was part ofthe last great aerial battle in theSolomons. The Japanese wereforced to turn their attention else-where as the American strategy ofisland-hopping began to gather mo-mentum. All the Marine Corps

Wildcat squadrons at Hendersonsoon transitioned to the next gener-ation of Marine fighter aircraft, theworld-beating Vought F4U Corsairwhich would also provide its owngeneration of Leatherneck aces inthe coming months.

James Swett transitioned to theCorsair and served with VMF-221when the squadron embarked inthe aircraft carrier USS Bunker Hill(CV17). By 11 May 1945, when heshot down his last victim, a Japan-ese kamikaze, he had a total of 15.5kills in Wildcats and Corsairs.

The Marine Corsair Aces ofBougainville and the Central

Pacific, 1943-44

The campaign and victory onGuadalcanal signaled the contain-ment of the seemingly unstoppableJapanese, and the beginning of thelong, but ultimately successful, Al-

lied drive through the Pacific toJapan. The first step of the longjourney began with the island withthe strange name.

Once secured, however, by 7 Feb-ruary 1943, Guadalcanal quickly be-came the major support base for theremainder of the Solomons cam-paign. While Marine ground forcesslugged their way up the Solomonschain in the middle of 1943, Alliedair power provided much-neededsupport, primarily from newly se-cured Guadalcanal. Marine andNavy squadrons were accompaniedby Army and New Zealandsquadrons as they made low-levelsweeps along the islands, or es-corted bombers against the harborand airfields around Rabaul. TheU.S. Army Air Force sent strikes byB-24 Liberators against Kahili, es-corted by Corsairs, P-38s, P-39s,and P-40s. For Marine aviators, itwas the time of the Corsair aces.

The First Corsair Ace

Because the Navy decided thatthe F6F Wildcat was a better carrierfighter than the F4U Vought Cor-sair, the Marines got a chance tofield the first operational squadronto fly the plane. Thus, MajorWilliam Gise led the 24 F4U-ls ofVMF-124 onto Henderson Field on12 February 1943.

As the Allied offensive across thePacific gathered momentum, thefighting above the Solomons andthe surrounding islands continuedas the Japanese constantly harassedthe advancing Allied troops. TheCorsair's first engagements weretentative. The pilots of the firstsquadron, VMF-124, had only anaverage of 25 hours each in theplane when they landed at Guadal-canal. The very next day, they wereoff to Bougainvile as escorts forArmy B-17s and Navy PB4Y Libera-tors. It was a lot to ask, but they didit, taking some losses of both

Marine mechanics service an early F4U Corsair, perhaps of VMF-124, on Guadalcanal inearly 1943. "Bubbles" is already showing the effects of its harsh tropical environment aswell as the constant scuffing of its keepers' boots. Note the Corsair's large gull wings andlong nose, which prohibited a clear view forward, especially during taxi and landings.

National Archives 127-N-55431

22

IIIIL'

Department of Defense Photo (USMC) 60940

Enlisting in the Marine Corps in 1933,lstLt Kenneth A. Walsh eventually wentthrough flight training as a private, gaininghis wings in 1937. By 1943, Walsh was inaerial combat over the Solomons and be-came the first Corsair-mounted ace.

bombers and escorts. While it was arough start, the Marines soon set-tled down and began to exploit thegreat performance of this new ma-chine, soon to become known to theJapanese as "Whistling Death," andto the Corsair pilots as the "BentWing Widow Maker."

After the first few missions, thenew experience with the Corsair'scapabilities began to really takehold. First Lieutenant Kenneth A.Walsh, a former enlisted pilot (hereceived his wings of gold as a pri-vate), shot down three enemy air-craft on 1 April. Six weeks later,after several patrols, Walshdropped three more Zeros on 13May 1943, becoming the first Cor-sair ace. By 15 August, Walsh had10 victories to his credit.

On 30 August, he was scheduledto fly escort for Army B-24s on astrike against the Japanese airfieldat Kahili, Bougainville. Walsh'sfour-plane section launched beforenoontime to make the flight to aforward base on Banika in the Rus-sell Islands. After refueling and

grabbing some lunch, the four Ma-rine pilots took off again to ren-dezvous with the bombers. As theescorts—more F4Us and Army P-38s—joined up with the bombers,Walsh's engine acted up, forcinghim to make an emergency landingat Munda.

A friend, Major James L. Neefus,was in charge of the Munda air-field, and he let Walsh choose an-other fighter from Corsairs thatwere parked on Munda's airstrip.Walsh took off in his borrowedfighter and headed toward Kahilito try to find and rejoin with his di-vision. As he finally approachedthe enemy base, he saw the B-24sin their bomb runs, beset byswarms of angry Zeros. Alone, atleast for the moment, Walsh piledinto the enemy interceptors whichhad already begun to work on theArmy bombers.

As Walsh fought off several at-tacks by some 50 Zeros, therebydisrupting to a degree their attackon the bombers, he wonderedwhere all the other Americanfighters might be. Finally, severalother Corsairs appeared to relievethe hard-pressed ace. As otheraircraft took the burden fromWalsh, he eased his damagedfighter east to take stock of his sit-uation. He was able to shootdown two Zeros, but the enemyinterceptors were nearly over-whelming. The B-24s were strug-gling to turn for home as moreZeros took off from Kahili.

Lieutenant Walsh managed todown two more Zeros before he hadto disengage his badly damagedCorsair. Pursued by the Japanese,who pumped cannon and machinegun fire into his plane, Walsh knewhe would not return this Corsair to

National Archives photo 80-G-54291

lstLt Ken Walsh of VMF-124 connects his radio lead to his flight helmet before a missionin 1943. He was the first F4U pilot to be decorated with the Medal of Honor, for a mis-sion on 30 August 1943, during which he shot down four Japanese Zeros before ditchinghis borrowed Corsair.

23

Major Neefus at Munda. SeveralCorsairs and a lone P-40 arrived toscatter the Zeros which were usingWalsh for target practice.

He ditched his battered fighteroff Vella Lavella and was picked up

by the Seabees who borrowed aboat after watching the MarineCorsair splash into the sea. For hisspirited single-handed defense ofthe B-24s over Bougainville, Lieu-tenant Walsh became the first Cor-

sair pilot to receive the Medal ofHonor. The four Zeros he shotdown during this incredible mis-sion ran his score to 20.

Ken Walsh shot down one moreaircraft, another Zero, off Okinawaon 22 June 1945, the day the islandwas secured. At the time, Walshwas the operations officer for VMF-222, shorebased on the newly se-cured island.

A series of assaults during thespring and summer of 1943 nettedthe Allies several important islandsup the Solomons chain. An am-phibious assault of Bougainville atEmpress Augusta Bay on 1 Novem-ber 1943, caught the Japanese de-fenders off guard. In spite of Japan-ese reaction and reinforcement, asecure perimeter was quickly estab-lished, and within 40 days, the firstof three airfields was in operationwith two more to follow by thenew year. Aircraft from these stripsflew fighter sweeps first, later to befollowed by daily escorted SBDand TBF strikes. With the establish-ment of this air strength at Bougain-ville, the rest of the island was ef-fectively bypassed, and the fate ofRabaul sealed.

Marine aircraft began flyingfrom their base at Torokina Point atEmpress Augusta Bay, the site forthe initial landing on Bougain-ville's midwestern coast. NavySeabees then quickly hacked outtwo more airstrips from the jun-gle—Piva North and Piva South.Piva Village was a settlement onthe Piva River, east of the airfieldcomplex.

The official Marine Corps his-tory noted that "whenever therewas no combat air patrol over thebeachhead, the Japanese werequite apt to drop shells into the air-field area. The Seabees and Marineengineers moved to the end of thefield which was not being hit andcontinued to work."

Profile by Larry Lapadura, courtesy of the artist

This VMF-124 F4U-1, No.13, was flown by lstLt Ken Walsh during his first combat tourin which he became the first Corsair-mounted ace.

Maj Gregory "Pappy" Boyington became the best known Marine ace. A member of theFlying Tigers in China before World War H, he later commanded VMF-122 before takingover VMF-214. By early January 1944, he was the Corps' leading scorer. Here, the colorfulBoyington, center, relaxes with some of his pilots.

Author's Collection

24