December 2001 Audubon Log Northeastern Wisconsin Audubon Society

Audubon Case final - CUNY IVE IVE Case.pdf · While there is no direct connection, the society is...

Transcript of Audubon Case final - CUNY IVE IVE Case.pdf · While there is no direct connection, the society is...

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

2

Introduction

As an organization dedicated to the protection of birds and other wildlife in its

city, New York City Audubon (NYCA) was naturally concerned about the fate of Pale

Male, a Red-tailed hawk whose nest above a window at a pricy Fifth Avenue building

had been removed. This incident positioned NYCA as a stakeholder in the resolution of

the controversy that followed and would have

an impact on the public perception of the

organization and its goals, its ability to

position itself as distinct from state and

national organizations with similar names and

goals, and its capability to enlist members and

raise funds. However for any of this to be

possible, NYCA had first to help bring the controversy to a satisfactory conclusion and to

answer the most fundamental questions about its character to determine whether their

mission even permitted them to capitalize on the opportunity presented by Pale Male and

the removal of his nest.

There are several levels of Audubon societies. While, in a general sense, the

national, state and local organizations all have as their mission, the protection of wildlife,

their focus can be quite different. In terms of membership and fundraising, there have

been several processes over time concerning the sharing and/or not sharing of members

and dollars. This has resulted in confusion among donors about where their money is

going, how it is being used and the distinctions and links among the levels of Audubon

© www.palemale.com

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

3

society. The Pale Male incident and the actions of the various Audubons highlighted this

confusion.

The Incident

After eleven years during which Pale Male had nested on a twelfth floor cornice

of a building overlooking Central Park in which apartments often sold for millions of

dollars, the nest was removed by workers after the co-op1 board determined that it must

go. Their reasoning was that the presence of the birds’ nest “had caused deterioration of

the building’s canopy from bird droppings. In

addition, the hawks bring live prey to the nest

where it is killed and torn for feeding.” This

resulted in the “danger of contamination,

Lyme disease and West Nile virus” and posed

a danger to pedestrians below (Lucek & Lee,

2004, p. 1). Bloodied carcasses sometimes fell from the nest. Richard Cohen, a real

estate developer who is the board president, said of the nest, “every year this became

more problematic.” He stated his belief that the birds would nest elsewhere, “it takes a

1 A co-op or cooperative is a type of dwelling in which cooperative members hold shares in a corporation that owns or controls the building(s) and/or property in which they live. Each shareholder is entitled to occupy a specific unit and has a vote in the corporation. Members elect a board of directors which is empowered to make governance decisions on behalf of the co-op. In addition, co-ops often have committees, such as a membership committee, maintenance committee, activities committee, and newsletter committee. Most co-ops hire a manager or management company to perform management functions. Every month, shareholders pay a maintenance fee, an amount that covers their proportionate share of the expense of operating the entire cooperative, which typically includes underlying mortgage payments, property taxes, management, maintenance, insurance, utilities, and contributions to reserve funds. There are many benefits to cooperative ownership. Some of these include personal income tax deductions, lower turnover rates, lower real estate tax assessments, reduced maintenance costs, resident participation and control, and being able to prevent absentee and investor ownership (National Association of Housing Cooperatives, 2005). There are some disadvantages which include disaffection and discontent among some shareholders who disagree with the decisions of the board and the feeling that cooperators give up some control of their home life to the will of the community.

© New York City Audubon

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

4

week to 10 days to rebuild a nest. Trees fall in nature. They lose nests. They are

resilient animals” (Lueck & Lee, 2004, p.2).

This was not the first time the co-op had attempted to remove the nest. In 1993,

shortly after the birds first appeared, the board ordered that the nest be taken down.

However, it soon became apparent that doing so violated a 1918 treaty signed by the

United States, Canada and Russia, and administered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Federal officials pressured the co-op to promise never to remove the nest again.

However, a 2003 clarification in the interpretation of the treaty permitted the co-op to

take its recent action, despite warnings from the building’s management company that a

public backlash might ensue (Lueck, 2004). They were right.

Regardless of the legalities of the situation, down on the ground, the hawk and his

current mate, Lola, had a following. Ever since he arrived in 1993 to build his nest, Pale

Male had attracted thousands of bird watchers, both locals and tourists, who would peer

up through high-powered binoculars and zoom camera lenses to observe him in his eight-

foot long nest, hoping that he would take flight, providing them with an opportunity to

witness his beautiful colors and four-foot wing span. Pale Male was the subject of

several documentaries and a book2 and is currently the subject of a website

(www.palemale.com). He is a New York celebrity.

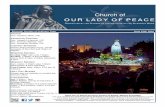

It was no small wonder, therefore, that the removal of the nest was to become a

cause. A storm of protest ensued, demonstrations and vigils were held, petitions signed,

shouts of “Bring back the nest” were heard from the street, emails arrived at the co-op,

disagreements arose among cooperative members, and there was even an arrest when a

prominent member of the co-op was allegedly menaced by a protester (charges of 2 Winn, Marie, (1999). Red Tails in Love. New York: Pantheon.

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

5

stalking and harassment were later dropped). A media blitz broadcast the plight of the

birds nationwide and indeed across the globe. In addition to all the local New York

newspapers, the story was covered by National Public Radio, The Associated Press, the

China Daily, The Xinhua News Agency, The Vancouver Sun, The Irish Times, The Daily

Telegraph (London), the Agencie France Presse, The Santa Fe New Mexican, the

Telegraph Herald (Dubuque, Iowa), cable and network news and many other media

outlets. Between December 8 and December 31, 2004, The New York Times published

fourteen articles, as well as numerous letters to the editor about Pale Male. Its editorial

on December 9, 2004 suggested that residents of the co-op could have at least learned to

“live with the hawks” (New York Times, 2004, p. A40).

This was a case of the rights of property owners vs. the demands of those

concerned with welfare of wildlife. There

were a number of stakeholders in this dispute:

the board of the cooperative, cooperative

members who were not board members who

both supported and opposed the board’s

action, neighbors of the co-op,

environmentalists, bird lovers and watchers, the media, as well as federal, New York

State and New York City governmental agencies. Amongst all the hoopla, many,

including the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, thought that,

even though the organization had been involved from the start, the logical entity to broker

a settlement of the dispute was the group most frequently associated with birds and

wildlife, the Audubon Society.

© www.palemale.com

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

6

The Audubon Society

While there is no direct connection, the society is named for John James

Audubon, a nineteenth century wildlife artist who specialized in painting birds. It is a

national organization which is synonymous with birds and bird conservation. Its mission

is “to conserve and restore natural ecosystems, focusing on birds, other wildlife, and their

habitats for the benefit of humanity and the earth's biological diversity” (Audubon, 2005,

p. 1). The society was founded in New York a century ago by outraged citizens who took

action against the killing of herons and egrets whose feathers were being used to decorate

ladies' hats. It provides educational programs to achieve its mission. This, however, was

not the Audubon Society that would be most closely associated with the Pale Male

incident.

New York City Audubon

There is actually a somewhat confusing network of Audubon societies on a

national, state and local level. The National Audubon Society, the national organization,

was founded in New York where their offices are still located. Logically, they have a

national focus. However, they do educational programs in New York City schools. In

New York, the state office of the national organization is known as Audubon New York.

The society most directly involved with the Pale Male incident was New York City

Audubon, a local chapter of the national organization. All three became stakeholders in

the Pale Male dispute.

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

7

NYC Audubon was founded in 1979 by a group who “believed that a voice was

needed for New York City's natural environment” (New York City Audubon, 2005). It

was specifically concerned with the protection of grasslands, woodlands, wetlands and

wildlife throughout the five boroughs of New York City and the preservation of the city’s

natural habitats. The mission of the chapter, while in line with the goals of the national

organization, was decidedly more local. According to its website, the mission of New

York City Audubon is to:

• Protect and preserve wildlife and wildlife habitats in New York City.

• Educate and inform members and the general public about environmental issues,

especially as they affect New York City.

• Study and enjoy birds and other wildlife, and foster appreciation of the natural

world, co-operate with the National Audubon Society and other conservation

organizations in furthering sound environmental practices.

• Serve as a resource and advisor to other groups concerned with specific

environmental issues.

• Defend and improve the quality of green spaces and the environment in New

York City for both wildlife and human beings (New York City Audubon, 2005).

The focus of the local chapter was, then, the environment and bird habitat within

the five boroughs of New York City3. Its conservation work started with the Grassland

Restoration and Management Program (GRAMP) at Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, a

3 According to the 2000 Census New York City has a population of over eight million people who live in one of five boroughs: Brooklyn, Bronx, Manhattan, Queens, and Staten Island. Of these, only the Bronx is connected to the mainland of the US. The rest of the city is comprised of over a dozen islands including Manhattan Island, Long Island, Staten Island, Ellis and Liberty Islands, Roosevelt Island and others. Water plays a major role in the city’s life and history. It faces the Atlantic Ocean and Long Island Sound and contains many bays, rivers, inlets, marshlands, and wetlands.

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

8

project which aimed to reclaim habitat for grassland species on 140 acres around Jamaica

Bay. Recognizing the need to further safeguard Jamaica Bay's coastal area, NYCA

participated in several efforts to develop strategies to preserve additional sites on this

fragile wetland.

NYCA also initiated the Harbor Herons Project, a program that monitors the

nesting patterns of colonial birds on uninhabited islands off Staten Island, the Bronx and

Queens. The scientific data collected from these extraordinary rookeries4 since 1983 has

been fundamental in assessing breeding success of egrets, herons, ibis, and other wading

birds, and negative impacts of oil spills in the Arthur Kill, a waterway that separates

Staten Island, a part of New York City, from New Jersey. In the fall of 1996, the chapter

launched a new study, inventories of neo-tropical migrants using the islands as stopovers.

In 1998, with the Linnaean Society of New York and the Urban Park Rangers, NYCA

conducted a survey of bird species in Central Park and found that the park housed more

species than at any time in its history. The Christmas Bird Count has become an annual

event.

New York City Audubon has a major educational component. Thousands of local

school children receive NYCA's nature publication Look Around New York City.

NYCA offers classes in bird identification and nature photography. (These are not to be

confused with the educational programs conducted in New York City by the National

Audubon Society.) Monthly membership programs (open and free to the public) are held

on such topics as marine life in Jamaica Bay, butterflies and moths of the region, wildlife

of the arctic tundra and more. The organization publishes The Urban Audubon, a bi-

monthly newsletter. 4 A rookery is a breeding ground or meeting place of social birds or mammals.

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

9

NYCA confronts important local issues and is a founding member of the Pure

Water Alliance, a coalition of activists dedicated to protecting New York City's drinking

water. Participating in National Audubon's Armchair Activist Campaigns, the chapter

also addresses national issues. In the last 25 years, New York City Audubon has

assumed a leadership role in environmental education and stewardship of the city's

grasslands, woodlands, wetlands and wildlife. Recently, it advised the Lower Manhattan

Development Corporation, the entity responsible for guiding the redevelopment of the

World Trade Center site, to ensure that the safety of migrating birds is considered in the

construction of the new buildings.

Organization, Structure and Funding

Like the other Audubon entities, New York City Audubon is a non-profit,

501(c)(3) organization.5 Its purpose is to serve some public good, in this case the

protection of wildlife in the city. It is a relatively small organization consisting of three

full-time employees: an executive director, a membership director and a program

director. Except for a part-time bookkeeper, all other work is done by volunteers. The

executive director provides leadership, serves as the public “face” for the organization,

does fundraising, and reports to a Board of Directors. Board members and volunteers

carry out the chapter’s programs and projects. Committees of the board, which focus on

specific issues such as membership, wetlands, wildlife/endangered species, newsletter,

5 A nonprofit is a tax-exempt organization that serves the public interest. In general, the purpose of this type of organization must be charitable, educational, scientific, religious or literary. The public expects to be able to make donations to these organizations and deduct these donations from their federal taxes. Legally, a nonprofit organization is one that does not declare a profit and instead utilizes all revenue available after normal operating expenses in service to the public interest (About.com). Organizations that are nonprofit entities are often granted 501(c)(3) status making them eligible to receive contributions that are tax-deductible under the Internal Revenue Code.

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

10

field trips and nature photography, meet regularly. A separate advisory council assists in

fundraising efforts.

Until 2002, those who joined the National Audubon Society were automatically

enrolled in NYCA. At that point, there were between eight and nine thousand national

members who were, by default, New York City Audubon members. In addition, local

Audubon organizations shared in the membership contributions to the national

organization, a practice known as dues-sharing. In the first year of a membership, the

local organization received the entire dues payment from National Audubon. After the

first year, the local chapter received five dollars for each person who joined national. In

2002, however, NYCA and other local Audubons across the country were notified that

dues-sharing would end, and as a result, they would become responsible for their own

membership and fund-raising. Now, anyone who joins National Audubon receives a card

which indicates that they are also members of the local chapter. However, NYCA and

the other chapters receive no part of their membership dues. National Audubon does

provide a stipend to the local chapters. Last year’s stipend to the New York chapter was

$18,000, much less than it received previously under the dues-sharing plan. While

NYCA is still provided with the names of those in the local area who have joined the

national organization, it was now required to identify and seek out potential members and

donors. NYCA currently has approximately one thousand direct members who have

made tax-deductible contributions at one of several levels (family, individual,

senior/student, see Appendix B for rates). NYC Audubon retains their entire membership

fee. About 75% of these direct members are also members of the national organization.

The chapter also receives financial support from foundations and corporations, as well as

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

11

from local, state and federal funding sources (New York City Audubon, 2005). (See

Appendix A, Annual Report.) Local fundraising efforts are, however, complicated and

sometimes hindered by confusion among donors resulting from the three levels of

Audubon societies. Even if they comprehend that several levels exist, givers have to

consider if they should, for example, give to the national, state or local organization. Or,

whether they should donate to both national and local Audubon. Their decision is further

confused by the fact that membership cards from the National Audubon Society indicate

that one of the benefits of membership is automatic enrollment in New York City

Audubon. On the other hand, from a fundraising and membership perspective, the local

chapters benefit from the prominence and name recognition offered by the National

Audubon Society.

As the local Audubon society, it should come as no surprise that NYCA was

heavily involved in the Pale Male case. The

bird’s presence in New York City offered a

raison d’etre for the very existence of an

organization such as NYCA. In a sense, Pale

Male had become an embodiment of NYCA’s

mission, highlighting the notion of wildlife as

an essential element of the New York City environment. The removal of the nest was an

incident of interest to New York City bird watchers and “outdoorsy activists” (Pinkerton,

2004, p. A33), the society’s natural constituency. Despite the fact that this species of

hawk is not endangered and that the bird had made its nest near the top of a tall building,

the Pale Male’s plight struck a chord with the inhabitants of Manhattan, as urban a

© New York City Audubon

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

12

landscape as there is with its canyons of glass and steel buildings. To a certain degree,

this may be attributed to biophilia, the notion that there is an “innate yearning to have

some direct contact with nature, even if it’s nothing more than a plant in a window box.

To biophiliacs, a bird in the park is worth more than million of birds in faraway bushes.

That might be illogical, but is surely natural” (Pinkerton, 2004). This concern, and its

manifestation in the case of the hawks, offers a rationale for supporting NYC Audubon

and its mission to protest wildlife and habitat for creatures living in or passing through

the city.

When they were alerted by a member that Pale Male’s nest was being removed,

NYCA staff members rushed to the scene. After consulting with the US Fish and

Wildlife Service, they ascertained that the co-op’s action had not violated any laws,

regulations, court decisions or the treaty. Still, they were determined to bear witness and

draw attention to what they considered to be a terrible wrong, and to act to save the birds’

nesting place. NYCA contacted the media, resulting in

segments on two local television stations and articles in two

newspapers. They were interviewed numerous times. New

York City Audubon officials were instrumental in

organizing the vigils and rallies. They received calls from

the co-op board and other interested parties who urged them

to seek a solution. Internally, a debate raged as to what an

acceptable solution might be. Discussions took place as to what compromises, if any,

would become the position of NYC Audubon. The guiding principle, however, was to be

the good of the birds and, in the view of NYCA, the best solution was the restoration of

© New York City Audubon

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

13

the nest. The decision was made that this is required for the good of Pale Male and Lola.

With representatives from the national organization and the New York City Parks

Commissioner, the executive director participated in the negotiations with the president

of the co-op board. Aided by the prestige of the president of the National Audubon and

fortified by the position determined earlier by the staff and directors of NYCA, Mr.

McAdams was party to the ultimate decision to restore the nest.

An Issue of Identity

On the surface, it would seem that the Pale Male incident and the leadership role

taken by New York City Audubon would have provided the local organization with

sufficient press and publicity to make the organization stand out, gain recognition as an

entity unto itself and perhaps provide opportunities to enlarge its membership and

funding base. However, its lack of brochures and the inadequacy of its website at the

time of the controversy impeded the short-term impact on membership. There was even

uncertainty as to whether it was proper to “use” the controversy to fundraise so as to

increase the ability of the organization to reach its goals and face challenges that were

sure to come later. Debate on this question raged among NYCA staffers and directors.

In addition, confusion continued throughout the controversy. For example, the

web site of the national organization indicates that “Local, State & National Audubon”

(Audubon, 2005) met with the co-op board to negotiate a solution to allow the birds to

restore their nest and return to their perch on the building. Coverage in New York City

newspapers similarly blended the identities of the local, state and national Audubon

societies. For example, in announcing the end of the standoff in which the co-op agreed

to build a cradle and guardrail to allow the birds to rebuild, The New York Times stated

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

14

that the agreement was “forged by Audubon Society and co-op officials” (Lueck, 2004),

without indicating which level of the organization brokered the deal. E. J. McAdams,

was quoted in the coverage of both The New York Times and the New York Post and

was specifically identified as the executive director of New York City Audubon.

How could the local organization have made use of the controversy to enhance its

image, forge its identity, separate from that of the state and national organizations? Was

it even proper to consider such issues or was it a betrayal of the organization’s mission

and focus to capitalize on the Pale Male

controversy to increase recognition,

membership, and funding? Would the specific

local mission of NYCA be advanced by

creating an identity of its own? If so, how so?

How could the publicity of the incident have

been best used to help the organization to better achieve its mission and goals? What will

be the long-range impact of the Pale Male incident on New York City Audubon?

Postscript

A fundraising effort that has resulted from the Pale Male controversy is the

creation of a New York City Raptor6 Fund by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation

which will match raptor-related fundraising efforts in the city. Partners in this endeavor

6 A raptor is a carnivorous (meat-eating) bird. “Birds of prey” is another term used to describe raptors as a group. All raptors share at least three main characteristics: keen eyesight, eight sharp talons, and a hooked beak. There are approximately 482 species of raptor worldwide, 304 diurnal (day-active) species and 178 nocturnal (night-active) species. As a red-tailed hawk, Pale Male is a raptor (The Raptor Center).

© www.palemale.com

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

15

will be both the local and national Audubon organizations and the New York City Parks

Department. New York City Audubon will benefit monetarily from this effort.

In an effort to foster its own identity, NYC Audubon has taken several actions.

With the assistance of a graphic designer who worked on a pro bono basis, it created a

new logo which is distinct from that of the state and

national organizations. It has used Pale Male

petition lists to reach potential members, informing

them of the necessity of supporting the local

organization in light of the ending of the dues-

sharing arrangement with National Audubon

(Appendix B). It has determined that future membership drives and fundraising efforts

will highlight NYCA’s successful efforts at getting the hawk’s nest restored. In addition,

since the Pale Male incident, NYCA has noticed an increased media interest in stories

about birds and wildlife in the city.

Even after an agreement was reached allowing them to return to their location on

the building, it is now clear that Pale Male and his mate Lola are rebuilding their nest.

According to NYCA Executive Director, E. J McAdams, “They seem not to have missed

a beat” (New York Post, 2004). No eggs have yet been laid as of February, 2005. In

light of the fact that Pale Male has fathered more than twenty offspring during his time at

the nest, experts have a reasonable expectation that eggs will be laid and hatched and

offspring fledged in the near future.

© New York City Audubon

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

16

References

Audubon, (2005). About Audubon. [Available at: www.audubon.org/nas/]

Audubon, (2005). Local, state, & national Audubon meets with ‘Pale Male’

building co-op board. [Available at

www.audubon.org/news/press_releases/Pale_Male_Meeting].

Kerlinger, P. (1999, June). Nesting in Gotham. Natural history. v. 108. no. 5,

pp. 24-26.

Lueck, T. J. (December 15, 2004). Co-op to help hawks rebuild, but the street is

still restless. The New York Times. [Available at: www.

nytimes.com/2004.12.15.nyregion/15hawk.html?ex+1]

Lueck, T. J, & Lee, J. (December 11, 2004). No fighting the co-op board. The

New York Times. Section A, p. 1.

National Association of Housing Cooperatives. (2005). About NAHC & Housing

Co-ops. [Available at www. coophousing.org/about_nahc.shtml].

New York Post. (December 31, 2004). How the nest was won: Hawks are back.

p. 17.

Pinkerton, J. P. (December 28, 2004). Fifth Avenue call of the wild. Newsday.

p. A33.

The New York Times. December 9, 2004) Squatting rights, editorial. p. A40.

The Raptor Center. (2005). Information about raptors. University of Minnesota.

[Available at:

www.ahc.umn.edu/ahc_content/colleges/vetmed/Depts_and_Centers/Raptor.

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

17

Appendix A

New York City Audubon Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2003

New York City Audubon’s mission is to celebrate, protect and conserve the city’s birds and their habitat. Dear Friends, Looking back over the previous fiscal year, New York City Audubon has accomplished much for the birds and people of New York City. Some highlights were: • Educated hundreds of New Yorkers on urban nature with the award-

winning film Pale Male and our children’s publication Look Around New York City.

• Spoke before the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation to insure that the design for the new World Trade Center site will be safe for migrating birds.

• Hired Emily FitzGerald as Administrative Assistant to increase our effectiveness.

• Advocated for a bike path that would not impinge on the habitat of the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge.

The following is an overview of NYC Audubon’s income and expenses for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2003. Total Support and Revenue $488,574 Program Expenses $210,708 Management and General Expenses $ 20, 420 Fundraising Expenses $ 20, 318 End of Year New Asset Balance $680,668 New York City Audubon is tax-exempt under section 501(c)3 of the Internal Revenue Code. Donations are tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law.

New York City Audubon - A Case Study by Richard Graziano, Ed.D. © Institute for Virtual Enterprise – A CUNY Special Initiative

18

Appendix B

New York City Audubon Membership Appeal Letter

September 2004

Dear Audubon Member,

We hope you have enjoyed New York City Audubon programs, field trips, classes and events available to you through your membership in National Audubon. For years, National Audubon has offered free membership in NYC Audubon as a benefit for New York City residents joining National Audubon. As you may have read in our newsletter, The Urban Audubon, NYC Audubon and other Audubon chapters around the country have begun DIRECT Chapter Memberships. We have initiated this new program because National Audubon can no longer offer financial support to chapters in the traditional dues-share method. We encourage you to join NYC Audubon so you can make a significant impact on conservation in the five boroughs. Since our founding in 1979, we have become a leader in urban bird conservation, education, advocacy and volunteer stewardship in New York City. Your generous support has led to NYC Audubon’s many successes. Members are essential to our work. When you join NYC Audubon as a DIRECT member, your contribution will help us continue our tradition of grassroots activism and local conservation right here in your own community. You will also receive:

6 issues of enlightening newsletter, The Urban Audubon Free Monthly Programs featuring speakers and slide shows on environmental topics Volunteer opportunities such as improving grassland habitat, monitoring flight patterns,

Christmas Bird Counts, beach cleanups and bird rescue Access to over 150 guided field trips to birding hotspots both near and far Discounts on trips and merchandise, including 20% off at Duggal Visual Solutions Exclusive invitations to events such as our recent gallery reception with Subhankar

Bannerjee and his stunning photographs of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge But the most important benefit of all is the diverse community you will join, dedicated to celebrating, protecting and conserving birds and their habitat in New York City. Annual membership is only $35 for individuals, $45 for family, or take advantage of the $25 rate for seniors and students. Simply complete the form below and mail it to our office in the envelop provided and we will send you the essential Checklist of the Birds of New York City as a special gift along with your membership card. Please call me at __________ if you have any questions or concerns. Thank you again for your commitment to Audubon, we hope you will join us today. Sincerely, Emily FitzGerald, Membership Director