ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK -...

Transcript of ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK -...

ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK PCR:TIM 34260

PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT

ON THE

EMERGENCY INFRASTRUCTURE REHABILITATION PROJECT

PHASE I (GRANT 8181 – TIM [TF])

IN THE

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF TIMOR-LESTE

October 2005

CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS

Currency Unit – US dollar ($)

ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CEM – Companhia de Electricidade de Macau CSP – consolidated support program DFID – Department for International Development DTW – Department of Transport and Works EDP – Electricidade de Portugal EDTL – Electricidade de Timor Leste EIRC – emergency infrastructure rehabilitation contract ETTA – East Timor Transitional Administration ICB – international competitive bidding IDA – International Development Association IS – international shopping LCB – local competitive bidding MOU – memorandum of understanding MV – medium voltage PMU – project management unit RAMS – Road Asset Management System RMRC – road maintenance and rehabilitation contract RPMG – Rural Power Management Group RRP – report and recommendation of the President TA – technical assistance TEU – twenty-foot equivalent unit TFET – Trust Fund for East Timor TOR – terms of reference UNDP – United Nations Development Programme UNTAET – United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor VMC – village management committee VOC – vehicle operation cost

WEIGHTS AND MEASURES

km (kilometers) – 1,000 meters kV (kilovolt) – 1,000 volts kVA (kilovolt ampere) – 1,000 volt-amperes kW (kilowatt) – 1,000 watts m (meters) – unit of length MW (megawatt) – 1,000,000 watts ton – 1,000 kilograms

NOTES

(i) The fiscal year of the Government ends on 30 June. (ii) In this report, “$” refers to the US dollars. (iii) The term Government refers to the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste. (iv) On 18 November 2002, the secretary changed the name from East Timor to the

Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste through Circular No. 51-02. Since the change in name occurred during project implementation, the report will use Timor-Leste as the country name. However, East Timor is also used when appropriate.

CONTENTS

Page

BASIC DATA i

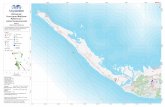

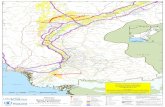

Map v

I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1

II. EVALUATION OF DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION 2 A. Relevance of Design and Formulation 2 B. Project Outputs 3 C. Project Costs 5 D. Disbursements 7 E. Project Schedule 7 F. Implementation Arrangements 8 G. Conditions and Covenants 9 H. Related Technical Assistance 10 I. Consultant Recruitment and Procurement 10 J. Performance of Consultants, Contractors, and Suppliers 10 K. Performance of the Recipient and the Executing Agency 11 L. Performance of the Asian Development Bank 11

III. EVALUATION OF PERFORMANCE 11 A. Relevance 11 B. Efficacy in Achievement of Purpose 12 C. Efficiency in Achievement of Outputs and Purpose 12 D. Preliminary Assessment of Sustainability 13 E. Environmental, Sociocultural, and Other Impacts 13

IV. OVERALL ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 14 A. Overall Assessment 14 B. Lessons Learned 14 C. Recommendations 15

APPENDIXES 1. Project Framework 16 2. Status of Compliance with Grant Covenants 19 3. Location of Road Works 26 4. Location of Power Stations 27 5. Plant Regional Depots 28 6. KPMG Contract 29 7. Electricidade de Timor Leste Management Contract 31 8. Consultants’ Studies 33 9. Project Implementation Schedule 35 10. Rural Power Management Group 37 11. Financial and Economic Evaluation 39 12. Rating of the Project 46

BASIC DATA A. Grant Identification 1. Country

2. Grant Number

3. Project Title 4. Borrower

5. Executing Agency 6. Amount of Grant

7. Project Completion Report Number

Timor-Leste

Grant 8181-TIM(TF)

Emergency Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project-Phase I

Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste

Ministry of Transport, Communications and Public Works

$29.8 million

PCR:TIM911 B. Grant Data 1. Appraisal – Date Started – Date Completed

2. Grant Negotiations – Date Started – Date Completed

3. Date of Board Approval

4. Date of Grant Agreement

5. Date of Grant Effectiveness – In Grant Agreement – Actual – Number of Extensions

6. Closing Date – In Grant Agreement – Actual – Number of Extensions

7 February 2000 28 February 2000

28 March 2000 29 March 2000

13 April 2000

19 April 2000

18 July 2000 19 April 2000 None

30 November 2002 25 July 2005 Four

7. Disbursement Initial Disbursement

30 August 2000 Final Disbursement

25 July 2005 Time Interval

58 months and 25 days Effective Date 19 April 2000

Original Closing Date 30 November 2002

Time Interval 31 months & 12 days

Category or Subloan Original

Allocation Amount

Canceled Net Amount

Available Amount

Disbursed Undisbursed

Balance 01 Port Rehabilitation 2,060,000 (864,384) 1,195,616 1,195,616 0 02 Road Rehabilitation 20,550,000 185,858 20,735,858 20,735,858 0 03 Power Rehabilitation 2,770,000 2,685,770 5,455,770 5,455,770 0 04 Consultancy Services (Project Management Unit)

3,050,000 (673,956)

2,376,044

2,376,044

0 Unallocated 1,370,000 (1,370,000) Total 29,800,000 (36,712) 29,763,288 29,763,288 0

ii

C. Project Data

1. Project Cost ($) Cost Appraisal Estimate Actual

Foreign Exchange Cost 29,800,000 29,763,288 Total 29,800,000 29,763,288

2. Financing Plan ($) Cost Appraisal Estimate Actual Implementation Costs Borrower-Financed ADB-Financed Other External Financing (TFET) 29,800,000 29,763,288 Total 29,800,000 29,763,288 IDC Costs Borrower-Financed ADB-Financed Other External Financing

Total 29,800,000 29,763,288 ADB = Asian Development Bank, IDC = interest during construction, TIM = Timor-Leste, TF = Trust Fund.

3. Cost Breakdown by Project Component ($)

Component Appraisal Estimate Actual I. Base Cost Emergency Port Rehabilitation 2,060,000 1,195,616 Emergency Road Rehabilitation 20,550,000 20,735,858 Emergency Power Rehabilitation 2,770,000 5,455,770 Project Management Unit 3,050,000 2,376,044

Subtotal A 28,420,000 29,763,288 II. Contingencies Physical Contingency 1,180,000 0 Price Contingency 160,000 0

Subtotal B 1,340,000 0 Total 29,760,000 29,763,288

4. Project Schedule

Item Appraisal Estimate Actual Date of Contract with Consultants Port Component Jun 2000–Jun 2001 Road Component Nov 2000–Jun 2002 Power Component Sep 2000–Dec 2004 PMU Component Jun 2000–Dec 2004 Completion of Engineering Designs Not applicable

(emergency) Civil Works Contract Date of Award May 2000, Jun 2000 Completion of Work Port Component Jun 2002 Road Component Jun 2002

iii

Power Component Dec 2004 Equipment and Supplies Dates First Procurement Dec 2000 Last Procurement Dec 2004 Completion of Equipment Installation Dec 2004 Start of Operations May 2000b Completion of Tests and Commissioninga Jul 2002 Beginning of Start-Upa Jul 2002

PMU = project management unit. a Due to the emergency nature of this project, other milestone dates cannot be determined. b As the ports, power, and road components were mainly for rehabilitation, the facilities were operated minimally. 5. Project Performance Report Ratings

Ratings Implementation Period

Development Objectives

Implementation Progress

19 April 2000 to 30 June 2004 S S

S = satisfactory. D. Data on Asian Development Bank Missions Name of Missiona

Date

No. of

Staff

No. of Person Days

Specialization of

Membersb First Review 26 May–2 Jun 2000 2 23 b, c Second Review 7–16 Aug 2000 3 27 b, c, d Third Review 31 Oct–14 Nov 2000 4 60 b, c, a, e Fourth and Midterm Review 14–28 Feb 2001 3 42 b, a, f Fifth and Joint Donor Mission 23 May–2 Jun 2001 2 22 b, a Sixth Review 2–11 Oct 2001 2 19 b, a Seventh Review 11–19 Apr 2002 3 27 b, a, g Eighth Review 17–26 Jun 2002 3 30 b, a, c Ninth Review 12–19 Nov 2002 1 8 b Tenth Review 11–22 Aug 2003 2 24 b, c Eleventh Review 27 Jul–6 Aug 2004 3 22 b, g, i Special Review 13–15 Oct 2004 1 3 b Project Completion Report C 30 May–9 Jun 2005 4 34 b, c, g, h a Include identification, fact-finding, pre-appraisal, appraisal, project inception, review, special loan administration,

disbursement, project review mission. If more than one of each type of mission, number consecutively as Review Mission 1, 2, etc.

b a - engineer, b - economist, c – project analyst, d – liaison officer, e – administrative officer, f – environmental officer, g – power economist, h – transport economist, i – resident representative.

C The Project Completion Report was prepared by Kiyoshi Taniguchi, economist and mission leader; Noris Galang, associate project analyst and mission member; transport economist consultant; and power specialist consultant.

I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION

1. In the democratic consultation of 30 August 1999, the people of East Timor voted overwhelmingly for independence. This set off a campaign of destruction in the latter part of 1999 that demolished much of the country’s infrastructure. In an emergency response, the internationally supported Trust Fund for East Timor (TFET) was established, under the trusteeship of the International Development Association, to finance measures to address the physical and social dislocation. Funding for the Emergency Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project–Phase I (the Project) was drawn from this fund. The Project was designed to (i) undertake emergency road repair works to facilitate efficient transport of humanitarian and security cargo, and to revive economic activity, (ii) expand the capacity of port facilities to reduce congestion in the shortest time, and (iii) reinstate power supplies. Through its emergency activities, the Project also was intended to support long-term development of the roads, ports, and power sectors, strengthen the local contracting industry, institute sustainable operation and maintenance systems, and provide capacity building for sector management. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) Board approved the procurement of materials, as well as the engagement of consultants from member countries of ADB, World Bank, United Nations, and other donors to TFET.

2. The report and recommendation of the President (RRP) clearly laid out the situation in the country in early 2000, and the urgency of the Project. 1 The project framework is in Appendix 1. The availability of TFET funds, rather than cost estimates, primarily determined the size of the Project. It was formulated in accordance with ADB’s Policies and Procedures for Rehabilitation Assistance After Disasters.2 Flexibility was built into project design to encourage optimal revision in scope as implementation progressed. Four project components were envisaged at appraisal. At appraisal, financing planned to be allocated as follows: port rehabilitation (6.9%), road rehabilitation (69.0%), power rehabilitation (9.3%), PMU (10.2%), and contingencies (4.6%). Project components foreseen at appraisal were in paras. 43–58 of the RRP. As presented in the RRP, scope of the Project included:

(i) Road rehabilitation including (i) road repair, (ii) equipment for road repair works, (iii) labor-based road and causeway reconstruction, and (iii) rehabilitation and reinstatement of bridges and depot facilities.

(ii) Port rehabilitation including (i) wharf extension at Dili Port, (ii) restoration of the landing craft slipway at Dili Port, (iii) restoration of the eastern container yard, (iv) provision of beach matting at Beacu, Betano, and Suai, (v) port repairs, and (vi) equipment for landing of goods.

(iii) Power rehabilitation including (i) rehabilitation of 15 power stations, (ii) rehabilitation and reinstatement of distribution lines, (iii) restoration of communications between Dili and power stations, (iv) replacement of destroyed Comoro power station switchgear, and (v) support to financial power sector management.

3. Road Rehabilitation. The road rehabilitation priorities included making emergency road repairs and restoring viable road conditions on all main arteries, establishing essential equipment for empowering the local contracting industry; constructing essential causeways and bridges where other accesses did not exist, establishing appropriate civil works contracts and contracting procedures, and promoting intensive labor-based construction contracts where possible.

1 ADB. 2000. Report on a Project Grant from the Trust Fund for East Timor to the United Nations Transitional

Administration in East Timor for the Emergency Infrastructure Rehabilitation Project. Manila. 2 ADB. 1988. Policies and Procedures for Rehabilitation Assistance After Disasters. Manila.

2

4. Port Rehabilitation. The ports component provided for Dili port rehabilitation, while other components subsequently were dropped (para. 2). The expansion and restoration of Dili’s port facilities included completion of a partial wharf extension, rehabilitation of a slipway, and paving of the eastern container yard at Dili port.

5. Power Rehabilitation. The power component included an assessment of the restoration needs for 21 damaged or destroyed power stations; establishment of financial and management controls; metering; various power station rehabilitation works, tools, instruments, equipment, radio, and repeater systems.

6. Project Management Unit. A PMU was provided to assume responsibility for project implementation, under the supervision of ADB and United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET). From late 1999, UNTAET governed Timor-Leste with a mandate to establish an independent government by May 2002. UNTAET also was to take interim responsibility for rehabilitation work and capacity building. The recipient of the project grant of $29.8 million, UNTAET’s role and relationship with ADB and the Project is clearly established in the RRP. Given the situation in the country in early 2000, the infrastructure components selected for inclusion in the Project, as well as the flexibility built into the project implementation arrangements, were appropriate to meet the emergency needs of the country.

II. EVALUATION OF DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION

A. Relevance of Design and Formulation

7. While the United Nations directly provided emergency humanitarian aid immediately following the upheavals, ADB and the World Bank agreed to coordinate closely on utilization of the TFET grant funds for assistance to other sectors. As lead agency, ADB was responsible for restoring the infrastructure sector, including transport, energy, telecommunications, and water and sanitation. ADB’s Board of Directors formally delegated authority to ADB management to approve selected projects within these ADB-administered sectors. Procurement was to adhere to ADB’s Guidelines on Procurement and Disbursement and other applicable guidelines. Compliance with grant covenants is in Appendix 2. The emergency nature of the project precluded advance preparatory technical assistance (TA) for project preparation. Location of all Project roads contract works and power stations is shown in Appendix 3 and Appendix 4.

8. Road Rehabilitation. In the road component, all appraisal objectives were relevant at completion. This included extensive capacity building among local contractors, consultants, and Government staff, as well as completion of physical works. The contract was revised, replacing a few planned international competitive bidding (ICB) contracts with 65 smaller packages, which enabled contractors of various sizes and capabilities to prequalify and participate. This change accelerated the emergency repairs and enhanced relevance of the Project with regard to capacity building in the local contracting industry. This contractual revision helped build sustainable indigenous capacity to implement road maintenance. Designed to optimize labor-intensive methodology, the Project achieved this without onerous “labor only” contractual requirements on contractors. With the Government continuously employing labor-intensive methods for road maintenance, skills will be enhanced and employment opportunities will be sustained.

9. Restoration of infrastructure and Government services was an overarching priority at project formulation and design. To this end, the Project contributed significantly stopping the deterioration of the road network, and to facilitating the movement of goods through Dili port. These were essential building blocks of future development of transport infrastructure. Additionally, creating and equipping regional transport depots was an essential first step

3

towards the creation of a sustainable road maintenance regime. These requirements identified at appraisal, which are necessary to support economic and social recovery, remained relevant throughout project implementation. Because of the absence of a formal Government and domestic executing agency, the Project faced unique and considerable challenges in generating stakeholder participation and ownership at appraisal. Throughout implementation, PMU and ADB staff closely involved key stakeholders, including the evolving Timorese Government. At the working levels, local ownership was achieved, particularly with the Roads Services Department where Timorese staff were involved extensively in the implementation of all road sector activities.

10. Port Rehabilitation. With regard to this component, the continued use of the physical facilities provided in the port of Dili confirms the relevance of the Project. Continued effective handling of cargo by the private sector also affirms the decision to delete provision of cargo handling equipment.

11. Power Rehabilitation. In the power component, all appraisal objectives were relevant to power sector rehabilitation, including provision of rural power stations, rehabilitation and reinstatement of distribution lines, support to the financial sector management, and establishment of a PMU. Concerns remain over the sustainability of rural power networks in certain areas.

B. Project Outputs 12. Road Rehabilitation. At appraisal, the road component outputs envisaged to (i) reinstate priority lengths of unstable, collapsed, subsided, or eroded road, (ii) restore functional drainage to priority road lengths, (iii) repair local areas of heavily damaged road pavement, (iv) provide appropriate river crossings where these are essential to the humanitarian effort, (v) refurbish regional transportation depots, as required, (vi) develop local road repair capacity by mentoring local contractors, and (vii) involve the communities in unskilled road repair activities.

13. Priority sections of road were identified and designated as the core road network. The core road network comprised approximately 1,249 kilometer (km) of an estimated 6,000 km total network. Due to the poor condition of the roads and budget limitations, repairing roads other than the core network under the Project was impossible. Thus, the key district and subdistrict capital feeder roads of about 600 km, part of the identified and designated 1,249 km core road network, was selected for repair under the Project.

14. Contract works were carried out on all roads, except for the road from Dili to Cassa, which was included in the program of the Government of Japan. Four regional depots were refurbished in Baucau, Dili, Maliana, and Same sometimes in with the support of Government funding. All depots were equipped with basic equipment necessary for routine maintenance and medium road repairs. This included four-wheel drive, 3-ton tipper trucks, cement mixers, pedestrian rollers, and the like. A complete list of equipment provided for the regional depots is in Appendix 5.

15. The PMU’s regional engineer trainers provided training directly, rather than the five ICB contractors, as originally envisaged. Community involvement in routine maintenance was implemented for about 1,445 km of core network. For the routine tasks of verge and drain maintenance, this mostly involved contracting communities.

16. Port Rehabilitation. For the ports component, outputs anticipated at appraisal included (i) completing the construction of a 48.7 meters (m) by 12.1 m extension to the main wharf, (ii) repairing the slipway in the eastern hard stand area, (iii) upgrading the eastern container yard, (iv) providing beach matting at Beacu, Betano, and Suai, and (v) providing equipment for

4

landing of goods. The first two items were packaged together and tendered as an international shopping (IS) turnkey contract. Both items were completed, though quality problems delayed the wharf extension by 1 year. The slipway has been used extensively by military and civilian landing craft, thereby delivering the expected output. The usefulness of the wharf extension is limited by its flexible response to lateral loading from ships alongside. This is due to the poor original design, rather than the additional project works. In practice, the water depth limits the use of the extension to smaller vessels.

17. Upgrading of the eastern container yard was carried out in two stages. In the first stage, a gravel surface was provide that effectively eliminated the preexisting soft conditions, permitting normal container yard operations. However, excessive dust became an environmental and safety concern in Dili town center. In 2002, the area was paved together with provision of security fencing, floodlights, fire fighting equipment, and refrigerated container power outlets. Beach matting for Beacu, Betano, and Suai was canceled. After the roads were repaired, the demand for goods to be landed at Beacu and Betano was minimal. At Suai, military and civilian users had provided similar equipment.

18. Power Rehabilitation. Project outputs anticipated for the power component at appraisal were (i) rehabilitation of 15 power stations, (ii) rehabilitation and reinstatement of distribution lines, (iii) restoration of communications between Dili and power stations, (iv) replacement of the destroyed Comoro power station switchgear, and (v) support for management of the power sector. Additional components added to the Project during implementation included provision of a management contractor for Electricidade de Timor Leste (EDTL), provision of metering equipment, and specialized studies.

19. Rehabilitation of Power Stations. The TA was completed for rehabilitation of 21 rural power stations, and ICB was carried out for all of them. However, the high tenders received required rebidding initially for 13 stations (including distribution facilities), and then ultimately for 14 stations (without distribution facilities). Bids on the turnkey contract were called, and procurement adhered to ADB’s procurement guidelines. A contract for rehabilitation of 14 rural power stations was signed on 5 February 2002.

20. As implementation proceeded, revisions were made to the main turnkey contract through three variation orders. These orders provided for (i) restoration of Gleno district power station, and increased capacity at Betano and Maubisse, (ii) additional distribution transformers and rehabilitation works for 20 kilovolt (kV) subtransmission lines, and (iii) rehabilitation of two additional subdistrict power stations at Fatululik and Fatumean, plus supplementary distribution systems in Covalima.

21. Rehabilitation and Reinstatement of Distribution Lines. Distribution rehabilitation was dropped from the main turnkey contract due to funds constraints. Distribution elements were reintroduced partially through the variation orders (para. 20), and using savings of $2.44 million from the port and roads components, plus remaining unallocated funds. Rehabilitation works for these distribution networks was not contracted. Rather, PMU handled the work directly using materials obtained through IS and local competitive bidding (LCB). The overall technical project output for the power component was applied to 16 power networks. Specifically, it provided (i) 22 generating units, totaling 3,650 kilowatt (kW), (ii) 10 step-up power transformers, totaling 5,960 kilovolt ampere (kVA), (iii) 31 distribution transformers, totaling 2,100 kVA, (iv) 83 km of new and rehabilitated 20 kV subtransmission lines, (v) 82 km of low-voltage distribution lines, (vi) 120 km of low-voltage home connection cable, and (viii) 5,203 consumer connections, of which 57% are new consumers.

5

22. Restoration of Communications Between Dili and Power Stations and Replacement of the Destroyed Comoro Power Station Switchgear. These components were dropped and transferred for Japanese financing.

23. Support for Power Sector Financial Management. In April 2001, KPMG (Australia) was awarded a TA project to (i) undertake corporate restructuring in the power sector, (ii) establish a customer database, metering, and billing system, and (iii) establish a financial management system as well as implement management and financial control procedures. The consultants started work in late April 2001 under a contract signed on 26 April 2001. However, the consultants abandoned the work in October 2001 after completing about 60% of their TOR. ADB staff evaluated the outputs and concluded they were entirely unsatisfactory. Discussion and analysis of this component is in Appendix 6.

24. Provision of a Management Contractor for EDTL. At the Government's request, the Project recruited a management contractor, using ICB, to take over management of EDTL for 3 years. Hydro Tasmania undertook the preparation of the draft management contract and the bidding process. After a protracted approval process, ICB was carried out in accordance with ADB’s Procurement Guidelines. However, ADB later deemed the selection process and the award of the management contract misprocurement, because it deviated significantly from ADB’s procurement guidelines. As a result, ADB withdrew from recruiting the management contractor. The appointed management contractor (Companhia de Electricidade de Macau-CEM, S.A., Macau) started fieldwork in January 2004, and assumed full management of EDTL on 1 March 2004. This procurement case is discussed in Appendix 7.

25. Provision of Metering Equipment. At the Government's request, 1,000 single-phase and 300 three-phase meters were installed for the consumers with no meters or with defective meters in mid-2001.

26. Coordination with US Support Group. The Project provided materials for generation and distribution rehabilitation works undertaken by the US (military) support group at Baucau, Manatuto, and Oecussi.

27. Studies. During project implementation, some individual studies were conducted. These studies, as well as a list of consultants engaged by PMU under the Project, are listed in Appendix 8. 3 The studies covered (i) a computerized road asset management inventory and routine maintenance planning system, which has been installed and made operational in the Department of Roads, (ii) an accounting system for roads, (iii) provision of tug and towage services for the port of Dili, (iv) river stabilization studies for important bridge sites, (v) preparation of procedures for labor-based road maintenance, (vi) preparation of a legal framework for selection and contract of EDTL management contractor, (vii) tariff and manpower review for EDTL, (viii) asset valuation for EDTL, (ix) management review, called Power Sector–Institutional Reform and Governance, and (x) review of broad technical and institutional needs of the subdistrict power stations, called Subdistrict Power Stations in Timor-Leste.

C. Project Costs 28. Road Rehabilitation. At completion, the cost of the roads component totaled $20.74 million, compared with the appraisal estimate (excluding contingencies) of $20.55 million. Specific subproject cost estimates were not prepared at appraisal. Rather, an overall budget was assigned, derived from available TFET funds. Utilization of local contractors under the IS

3 In addition, ADB funded a separate TA (No. 3401-TIM: Transport Sector Restoration Project). This study,

undertaken concurrently with project implementation, made significant impacts on the subsequent development plans for the sectors concerned.

6

procedures is believed to have enabled the construction of more civil works subprojects than would have otherwise been possible under limited ICB contracts. Savings resulted from dropping the purchase of plant and equipment, where the private sector could adequately deliver the necessary services.

29. Port Rehabilitation. The final cost of the ports component was $1.20 million, compared with an appraisal estimate of $2.06 million. Savings accrued through cancellation of cargo-handling equipment ($730,000) and beach matting ($90,000). The wharf extension and repairs to slipway were executed as a single contract package for $325,000 (including design and supervision), compared with an appraisal estimate of $440,000. However, the increase in scope to refurbish the east container yard cost $854,000 (including design and supervision), as opposed to the RRP allocation $200,000. The RRP allocation of $600,000 for miscellaneous emergency repairs, therefore, was utilized to fund this increased scope.

30. Power Rehabilitation. The power component, which was modified extensively during implementation, was supplemented by the net savings from the roads, ports, and PMU components, as well as by surplus physical and price contingencies. The final cost of this component was $5.46 million, almost double the appraisal assessment of $2.77 million.

31. Project Management Unit. PMU consultancy costs totaled $2.38 million, compared with the RRP allocation of $3.05 million. Savings were achieved principally through a reduction of consultant inputs. The appraisal estimate of 48 person-months for road maintenance engineers was reduced to 31.8 person-months, while the power specialist was reduced from 24 person-months to 7 person-months. The 24 person-months allocated at appraisal for a ports engineer were not utilized. On the other hand, the allocation of 6 person-months for the chief technical adviser was increased to 20 person-months, with the incumbent also assuming responsibility for the port civil works. Additional savings accrued through recruitment of an individual consultant for the financial adviser position, as opposed to recruitment through a firm, as originally budgeted. During implementation, specialist services for geotechnical advice, river training, road asset management, and financial management were procured under the PMU component. The costs for these were covered from savings. A comparison of actual costs with RRP estimates is shown in the table.

Cost Breakdown by Project Components ($ million)

Component Appraisal Estimate Actual A. Base Cost 1. Roads 20.55 20.73 2. Ports 2.06 1.20 3. Power 2.77 5.45 4. Project Management Unit 3.05 2.38

Subtotal A 28.43 29.76 B. Contingencies 1. Physical Contingency 1.18 0.00 2. Price Contingency 0.16 0.00

Subtotal B 1.34 0.00 Total 29.77 29.76

Source: Asian Development Bank estimates.

7

D. Disbursements

32. At appraisal, project completion was anticipated by 31 May 2002. However, extensions were granted up to 31 December 2004. The roads and ports components were physically completed by 30 June 2002. Thus, the disbursement schedule was affected significantly only by the power component, which was revised and extended substantially during the latter phases of implementation.

33. For expediency of project implementation, as well as for handling the increase in volume of claims from contractors, the imprest account was strongly recommended to ensure that the works were carried out continuously, and that target disbursement requirements for the Project were met.

E. Project Schedule 34. Under the Grant Agreement, the Project was to be implemented from April 2000 to May 2002. The project implementation schedule for phase one of the Project is in Appendix 9.

35. Road Rehabilitation. Difficulties in recruiting and establishing personnel in regional offices, as well as consequent delays in refurbishing the depots, delayed the start of skilled and unskilled maintenance activities for the roads component. As a result, the community-based maintenance program did not disburse funds to the rural areas to the extent anticipated. Some savings were diverted to "works by contract”. Some of the initial emergency infrastructure rehabilitation contracts (EIRC) were extended to continue employment of major plant in the field until the road maintenance and rehabilitation contracts (RMRC), which had defined scope and bills of quantities, could begin. After the extremely wet season in 2000, a strategy was implemented to position contractor’s plants in all areas of the country to respond quickly to road blockages. During implementation, all backlog and periodic maintenance contracts were supposed to be completed by 31 December 2001. Contractors generally were slow, and did not complete contract works within the allotted time. By adjusting scopes of work, as well as the number and size of contracts awarded, the intended volume of work could be completed by 30 June 2002. However, the road works program was completed one month later than envisaged in the RRP.

36. Port Rehabilitation. The paving of the eastern container yard to the originally proposed gravel standard, and the rehabilitation of the slipway, were completed on schedule by September 2000. A second phase of work to improve the eastern container yard to a higher standard was added to the original scope of work. This phase was completed in June 2002. Concrete quality problems delayed the wharf extension, which opened in the second half of 2001.

37. Power Rehabilitation. The power component underwent substantial changes. Net savings from the PMU, road, and port components were reallocated to the power component, significantly increasing rehabilitation expansion activities. The physical project completion date was extended to 31 December 2004 to accommodate the significant enlargement of the power component. Two consecutive severe wet seasons that adversely affected the field works aggravated delays.

38. Overall, the RRP underestimated time schedule. Further, the decision to empower the PMU with the authority of an executing agency was not appropriate, because it created some conflict with the UNTAET at the time.

8

F. Implementation Arrangements 39. Project Management Unit. In the absence of an operating power utility, the PMU was established in May 2000 to implement the Project. The structure remained as envisaged in the RRP. PMU was headed by a project manager, assisted by a project accountant and three subsector engineers, all of whom were Timorese. International advisory staff included a chief technical adviser, a financial advisor, and three engineers (roads, ports, and power). Adjustments to international staffing were made at times during implementation, and short-term specialists undertook studies and assignments.

40. The Grant Agreement gave PMU the authority of an executing agency, empowering it to procure goods and services with oversight from UNTAET and ADB. Later in the project cycle, PMU’s role in procurement and administration became somewhat misunderstood as the Government developed its own capability. While efforts were made to curtail PMU’s autonomy, PMU reached compromises to support and utilize Government systems.

41. At appraisal, PMU was intended to become the core of the new Roads Services Department. However, this did not occur due to the establishment of the internationally staffed United Nations Infrastructure Department, which selected its own permanent domestic staff. Nevertheless, PMU was responsible, through regional engineer trainers, for the training of public service staff in regional offices. Later, PMU coordinated closely with the Roads Services Department to transfer skills in contract management.

42. Roads Rehabilitation. The exceptionally severe wet season of 1999 caused dramatic deterioration of the roads. In May 2000, traveling by road from the north to south coast was impossible, because of many land slips and washed out road sections. Funded by the Government of Norway and the Department for International Development (DFID), a program of emergency repairs began in late 1999. However, the most severe problems arose when these funds were nearing exhaustion. The Project took over existing contracts, which were administered based on field works orders issued, with $581,000 disbursed. Due to the adverse weather conditions, the work undertaken was more temporary, though essential to reopening key routes to humanitarian traffic. These are referred to as bridging contracts.

43. Five IS contracts totaling $518,500 were awarded in June 2000. At appraisal, these contracts were envisaged to be labor intensive. However, reconciling the need to perform the works urgently and the need to generate employment for economic recovery proved difficult. In many instances, excavation quantities were beyond labor intensive capability. Nevertheless, equipment shortages ensured that labor-intensive methods were maximized. Contracts were let on a “cost plus” basis, with schedules of rates for labor, plant, and materials. All basic contracts were completed by February 2001. Additional work orders were given to keep the contractors in the field over the wet season in 2001.

44. ICB originally had been intended for all maintenance within each region. Contractors engaged through ICB were supposed to mentor local contractors. However, the effectiveness of ICB maintenance contracts (for which only $2 million each was available) was determined to be limited and restrictive, with an overly high proportion consumed by overhead. Thus, the training budget was reallocated to PMU’s regional engineer trainers to support domestic regional engineers and maintenance staff in developing institutional maintenance capacity. Regional offices were used for supervision of maintenance work under small contract packages. A combination of local and international contractors, prequalified to undertake works of ceiling values commensurate with their respective capacities, undertook the physical works.

45. Contractors were invited to prequalify in three categories: (i) up to $50,000, (ii) up to $200,000, and (iii) up to $1 million. The lowest category was for Timorese contractors with

9

minimal equipment, and for labor-intensive works such as drainage repair, clearing, and minor slip reinstatement. The other two categories were aimed at international contractors, as well as larger domestic contractors with experience and appropriate plant and equipment. The Government later adopted this list of prequalified bidders for its own works program. Bids were invited for defined work scopes, using bill of quantity type contracts. The Project awarded 66 RMRCs, valued at $11.3 million.

46. Implementation of the community-based maintenance program required considerable inputs from the newly established regional engineers and their supervisors. Detailed community consultations, involving more than 400 community groups, were required to ensure that obligations were fully understood. Various modalities were explored, including (i) grouping communities under a locally appointed supervisor or coordinator, paid from the budget for the particular road lengths, and (ii) appointment of local leaders to be responsible for the road in their particular area. The former method proved to be administratively more convenient, reducing the number of contact points that regional offices had to deal with. The slow selection and approval of staff for regional offices by the Government’s public service authorities delayed the program.

47. Port Rehabilitation. Two civil works contracts for paving the eastern container yard to the appropriate gravel standard, repairs to the slipway, and the completion of the wharf extension were let in June 2000. The eastern container yard works were completed without problems. However, concrete quality problems delayed the wharf extension work. Deficiencies in the contractor’s quality control procedures during construction took 9 months to resolve, delaying the use of the facility. A contract to pave the eastern hard stand, which was let following IS procedures in February 2002, was completed in June 2002. This contract included lighting, fire fighting equipment, power outlets for refrigerated containers, and fencing.

48. Power Rehabilitation. A turnkey contract was signed on 5 February 2002 with an international company for provision of goods, supply, installation, commissioning, and training for 13 subdistrict and one district power stations. The contract subsequently was amended through three variation orders to add three more power stations. That increased the total to 18 power stations for rehabilitation, including two district power stations. The variation orders also provided for equipment and materials to be used for expansion of distribution networks.

49. PMU coordinated and implemented directly other activities required to restore the power supply. A task force for the execution of all restoration and expansion activities was set up, comprising two crews of skilled workers, supported by locally hired unskilled workers. PMU handled administration, procurement of materials and equipment, tools, logistical support, etc. An internationally recruited line supervisor provided guidance to the rehabilitation task force, while the PMU power engineer supervised the management of the entire structure. The execution of the rehabilitation works provided valuable on-the-job training for local linesman and consumer connection crews, as well as local employment of about 630 person-months. Training in day-to-day operation and routine maintenance was provided for two local operators for each power system. Forty operators were trained, with some of these integrated into the PMU rehabilitation task force. Details of the recommendations of the ADB power sector study are in Appendix 10.

G. Conditions and Covenants 50. With no conditions of effectiveness, the Grant Agreement became effective immediately upon signing. Commercial insurance entities regard Timor-Leste as extremely high risk, and

10

insurance cover is generally unavailable. No covenant or condition of the Grant Agreement was modified, suspended, or waived during project implementation. 4

H. Related Technical Assistance 51. Transport Sector Restoration (TA No. 3401). This TA began slightly ahead of the Project in May 2000. The objectives were to (i) prepare a comprehensive transport sector study covering the three transport modes in Timor-Leste, and (ii) develop an integrated plan for an efficient and effective multimodal transport system. After studying the road network and its condition, the TA provided road investment plans for maintenance and capital improvement. This resulted in the publication in May 2002 of Transport Sector Plan for East Timor, which conveyed a clear sectoral overview. 5 Subsequently, the report formed the basis of the sector investment plan prepared for the May 2004 Development Partners Meeting in Dili.

I. Consultant Recruitment and Procurement 52. The Grant Agreement established procedures for the employment of consultants in Section II of Schedule 3. ADB took the lead in recruiting PMU staff in agreement with UNTAET. Thereafter, PMU arranged consultant contracts following the procedures in the Grant Agreement. The Project employed consulting firms and individual consultants in coordination with ADB and UNTAET, as circumstances required.

53. Except for the problems in selecting the management contractor for EDTL (Appendix 7), no significant difficulties arose with consultant selection, packaging contracts, preparation of tender documents, or bid evaluation. PMU worked closely with UNTAET and ADB to ensure that selection criteria and contract award recommendations were agreed in advance, and in line with ADB’s procurement guidelines. Minor disbursement problems for the large number of small, local consultants’ contracts and contract extensions easily were resolved administratively between PMU and ADB’s project officer. Overall, the recruitment and procurement processes under the Project were satisfactory and effective.

J. Performance of Consultants, Contractors, and Suppliers 54. Roads Rehabilitation. Generally, civil works contractors under the roads component had limited experienced, sometimes resulting in less-than-satisfactory performance. Given the objective to improve local contracting capacity, local contractors were expected to face some technical difficulties. As such, completion time and liquidated damages were not strictly enforced under road contracts. Similarly, the road contracts program made allowances for the lack of experience of local resident engineers and supervisors to support the key objective of building capacity through direct job experience. In cases of extremely poor performance and lack of commitment, individuals were replaced. The performance of international consultants was deemed generally satisfactory.

55. Port Rehabilitation. In the port component, work scopes were closely defined, and international contractors executed all the contracts. Time limits were enforced, and liquidated damages were applied for late completion of the wharf extension.

56. Power Rehabilitation. An international contractor executed the main scope of work of the power component. Liquidated damages were applied for late completion. In general, the performance was satisfactory. The utility financial development subcomponent provided $800,000 for consultancy in power sector financial management. This work had three main aspects: (i) corporate restructuring, (ii) establishment of a consumer database, and (iii) 4 Appendix 2 shows the compliance status of all major conditions and covenants for the Project. 5 ADB. 2002. Transport Sector Plan for East Timor. Manila.

11

establishment of financial management capacity. The contracted firm failed to complete 40% of the work, abandoning the assignment some four months ahead of schedule. 6

57. The performance of the consultant engaged to develop financial management systems for the infrastructure departments was also unsatisfactory. The consultant failed to coordinate with the appropriate authorities, and reported too late for any comment or feedback to be made on the work. Therefore, implementation of intended recommendations was impossible. The consultant’s remuneration was reduced to reflect partial TOR delivery. Overall, the performance of the contractors, consultants, and suppliers was rated partly satisfactory.

K. Performance of the Recipient and the Executing Agency 58. UNTAET was the recipient of the grant proceeds until 2001, when the East Timor Transitional Administration (ETTA) was established and took over. The elected Government became the recipient when it assumed office in May 2002. The recipients generally performed satisfactorily in ensuring that the Project was implemented expeditiously. Initially, payments were processed quickly. However, some procurement was delayed later by the requirement for approval from the recipient’s tender committee, as well as from ADB, for awards of more than $100,000. Friction developed between ETTA’s director general for infrastructure and ADB over a number of issues, particularly the administration of the KPMG contract, which deviated from ADB’s instructions. UNTAET’s internationally recruited director general for infrastructure unilaterally converted KPMG’s contract from cost-plus to lump-sum, and deleted a large portion of the contracted work. The business relationship between ADB personnel and the director general became increasingly acrimonious. At one point, PMU and its consultants were forbidden to meet ADB missions or discuss any project matters. The justification was that ETTA, as a grant recipient, had full independence to modify the Project, even if that meant deviating from ADB procedures and guidelines. Eventually, the director general for infrastructure left Timor-Leste, and relations with the permanent Timor Government officials improved considerably.

59. Other difficulties were reported in the area of disbursements, particularly in clearing applications for replenishment of the special account. Given the weakness in the evolving, political, and institutional environment at that time, the performance of the Government and Executing Agency was rated partly satisfactory.

L. Performance of the Asian Development Bank 60. ADB played a major role in monitoring the Project, fielding review missions approximately every three months. Approvals of contract documentation and contract awards were generally received in a timely manner. ADB had to adjust to evolving institutional changes during the Project—from UNTAET to ETTA to the current Government. Overall, the performance of ADB in providing support and advice to PMU and the grant recipient was highly satisfactory.

III. EVALUATION OF PERFORMANCE A. Relevance 61. The design of the key elements of the Project was relevant to addressing the physical needs of the sectors concerned. The Project provided immediate assistance by rehabilitating road sections in Dili and selected districts, as well as by building the capacity of the local construction industry. Overall, the Project was rated relevant.

6 This case is discussed in Appendix 6.

12

B. Efficacy in Achievement of Purpose 62. In the roads component, much still needs to be done to improve work standards. Under the Project, road benches were stabilized. In addition, much work was done to restore drainage, thereby reducing the risk of future damage from floods. Through road rehabilitation, road safety was increased. Reliable access generally was restored throughout the main road network, although continuing slips are inevitable due to the weak and eroded geotechnical conditions. Strong and responsive road maintenance capability will be critical in the future, particularly the capability and availability of equipment to clear flood damage and unblock roads rapidly. In the ports component, the Project exceeded the original scope. Due to the extension of the third berth, congestion of ships was reduced. Paving the eastern hard stand and the slipway created a sustainable facility that will continue to benefit efficient port operations and improve the city environment. The power component also went beyond the original scope of work. Savings transferred to the power component enabled the Project ultimately to restore 18 rural power systems, and to include the rehabilitation and expansion of related distribution systems. Sustainability remains a major issue in the rural power sector. Overall, the Project was rated efficacious.

C. Efficiency in Achievement of Outputs and Purpose 63. In the roads component, the extensive use of community labor, local contractors, and direct management of the local workforce contributed significantly to sustainability, capacity building, and the improvement of rural economies through job creation. In the ports component, international contractors were used for all works at Dili port. The design standards applied were cost-effective and appropriate. In the power component, an international turnkey contractor was retained to rehabilitate all power stations, while PMU implemented associated distribution rehabilitation works. Use of local skilled and unskilled workers under the supervision of PMU permitted significant savings, which maximized distribution systems expansion by providing increased benefits to consumers within the budget provisions.

64. Financial Evaluation. Detailed financial evaluations were not carried out for the port or power components. A financial evaluation was not appropriate for the road component. The port is financially viable, with port revenues exceeding recurrent costs by a significant margin. The reported revenues from the power stations do not meet operating costs, and none of the district and subdistrict power stations is financially viable. Detailed discussions are in Appendix 11.

65. Economic Evaluation. Formal economic evaluations could not be carried out due to the emergency nature of the Project and lack of data. The road component is considered highly viable, with unrestricted traffic flows over the core road network producing large benefits. The port component generated its main benefits immediately after completion. As port traffic has declined, the extra capacity provided by the Project is not producing significant ongoing economic benefits. The power component is not considered economically viable, because the majority of the power stations are not functioning. Since the road component was much larger than the others, the overall Project is considered viable. Detailed discussions are in Appendix 11. The Project provided economic benefits to some of the local residents who received direct access to the Project (roads, port, and power services). The Project also generated direct and indirect local employment. ADB was effective in helping to resolve issues related to project administration.

66. Overall, the Project was rated efficient.

13

D. Preliminary Assessment of Sustainability 67. Considerable follow-up action will be required in the roads sector to ensure sustainability. The physical work and capacity development conceived at appraisal are complete. However, the unstable terrain will require annual clearance of slips, as well as continual restoration of road surfacing, benches, and drainage. The Project provided sustainable operational regional depots for routine maintenance, and introduced an appropriate implementation methodology. The Timorese staff will continue to require training and motivation, which is provided for in the second phase of the Project. PMU estimated the annual road maintenance funding requirement at $8.1 million, exceeding projected Government funding for routine maintenance of roads, even for the core network alone. Thus, deterioration might be inevitable if funding and maintenance initiatives are not increased. The port is fully sustainable, with recurrent costs funded by revenues. Power supply was restored in 16 locations. Electricity was made available to some 5,200 rural households and commercial consumers, of which about 57% are connected for the first time. An estimated 35,000 rural people will benefit from the Project. Community-based power management structures have been adopted in the subdistricts for (i) arranging the tariff structure, (ii) collecting tariffs and fees, (iii) disconnecting nonpaying and illegal consumers, and (iv) purchasing fuel and oil. Community feedback remains positive, and in certain areas these systems are operating successfully. Demand exists for expansion of the distribution networks, which would improve the economies of scale.

68. Sustainability of this investment is of great concern. Evidence suggests that some subdistricts are experiencing severe operating difficulties. Although EDTL is administratively responsible for these rural works, it reports inadequate staffing, equipment, and funding to support rural electrification. PMU, which has been active in supporting emergency repairs in these communities in the past, will soon cease operations under the Project. Thus, a longer-term solution is needed.

69. ADB funded study suggested that the main reasons ascribed for the nonfunctioning of power stations are (i) lack of collected funds in communities to buy diesel fuel, (ii) use of unpaid operators and fund managers, (iii) insufficient cash security at the community level, (iv) need for cash payment for fuel in Dili before deliveries, (v) technical and financial inability to fund and restore generators and distribution networks damaged by storms (and other causes), (vi) inability of certain subsistence-level communities to afford diesel fuel, even for minimal operation, without external assistance, and (vii) lack of expertise by village operators in troubleshooting technical problems as they occur, with even minor faults causing lengthy outages. The study concluded that the Government’s budgetary and technical commitments to subdistrict power stations are indispensable for sustainability of the rural power supply. 7 Sustainability was rated as unlikely.

E. Environmental, Sociocultural, and Other Impacts 70. The Project had a positive environmental impact by promoting the economic and social development of Timor-Leste, and facilitating reconstruction and redevelopment. There were no negative impacts. In the roads component, drainage repairs decreased erosion, and the works prevented landslips. As land acquisition was not required for the Project, no persons were displaced. In Dili port, pavement construction eliminated the dust problem in central Dili. Overall, the Project assisted socioeconomic recovery in rural areas at a critical time by providing extensive employment and capacity building. Sustainable employment will be provided in the future through continued use of systems developed for routine maintenance work by community labor. Overall, restoration of nationwide road access and provision of power services allowed

7 Details of the recommendations of the ADB study are in Appendix 10.

14

other humanitarian and reconstruction activities to proceed, thus assisting in normalization of social conditions. Thus, the Project produced moderate positive impacts.

IV. OVERALL ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS A. Overall Assessment 71. Implementation proceeded largely as conceived in the RRP, and the Project remains relevant after completion. The Project might be regarded as partly successful, because sustainability is lower than anticipated at project preparation (Appendix 12). Sustainability of the power component was very unlikely at project completion. However, as the Government complies with its commitments under the First Consolidated Support Program (CSP),8 success is anticipated over time. Further, this will allow time for EDTL’s recent success in the high-priority rehabilitation of Dili’s power supplies to be expanded gradually to the districts and subdistricts. This might be expected possibly by mid-2006.

B. Lessons Learned 72. Overall Project Responsibilities. ADB provided the grant to UNTAET, which was responsible for project administration. ADB’s authority to supervise and control the Project became controversial. At one point, UNTAET’s director general for infrastructure forbade ADB-financed consultants, including PMU, to discuss project issues directly with ADB missions. This conflict undermined ADB’s ability to enforce compliance with its guidelines. Care must be taken in the future to ensure that the role of ADB supervisory staff is carefully defined, and not in any way compromised.

73. Contracting Procedures. The Project was designed as an emergency response to address physical and institutional reconstruction. From the physical point of view, the Project was implemented successfully, largely within the project schedule. Considerable capacity building was achieved. The original plan to use ICB for civil works was dropped in favor contracting among prequalified bidders. In certain cases, however, this arrangement produced less-than-satisfactory civil works.

74. Sustainability of Roads. After project completion, many of the road rehabilitation works were damaged again by floods, requiring additional repairs. The PMU component generated about $500,000 in savings. Whether the savings might have been used to improve works supervision, thereby enhancing sustainability, is conjecture. In future emergency rehabilitation cases, this aspect should be taken into account.

75. Sustainability of Rural Power Generation. The donors incorrectly assumed the general commitment of the subdistrict communities, as well as their ability to organize. The experience in Timor-Leste raises questions about relying on community-managed power supplies without the full commitment of administrative, technical, and budgetary support from the Government. While community-based service provision in the rural areas of developing countries has become a standard international development practice, it should not be taken for granted. In many countries, including Timor-Leste, mounting evidence suggests that community service systems will fail without committed central support. The project performance audit report prepared for ADB’s water and sanitation rehabilitation project reached similar conclusions.9 Therefore, leaving such programs to communities alone, without specifically defined and carefully measured Government support, is inappropriate.

8 The World Bank. 2005. Consolidated Support Program. Dili. 9 ADB. 2004. Project Performance Audit Report on the Water Supply and Sanitation Rehabilitation Project – Phase I and Phase II. Manila.

15

76. Project Schedule. When designing an emergency, post-conflict infrastructure project, careful consideration should be given to the Government’s capacity to undertake the project implementation and other factors, such as weather patterns and geotechnically unstable terrain, to come up with a realistic project implementation schedule.

77. Project Formulation and Implementation. Under an emergency, post-conflict infrastructure project, policy dialogue is not the focus. Rapid estimates of economic return have to be made. To ensure maintaining standards for civil works, the executing agency should monitor the progress of the Project carefully.

C. Recommendations 78. Roads. Recommendations for the roads component include:

(i) The continuity of the maintenance regime established under the first phase of the Project must be monitored and supported. The provision of a regional engineer advisor under second phase of the Project will be a key to the maintenance regime.

(ii) The road asset management system developed under the Project needs continuing support of the second phase regional engineer adviser, and should be used for preparation of future annual road maintenance budget estimates.

(iii) The prequalification system for contractors for civil works has been transferred successfully to Ministry of Transport, Communications and Public Works. If used for procurement purposes under the second phase of the Project, a careful review should be undertaken of changes to the system since it was handed over to the ministry.

79. Ports. Port facilities are adequate for the anticipated volume of traffic over the next 10 years. An expansion is not expected to be required. 80. Power. The Government committed to adopt a proactive approach to addressing the successful operation of the donor-financed subdistrict power systems. This primarily will entail

(i) creating a rural power management group, as discussed in Appendix 10; (ii) EDTL assuming full and early responsibility for repair and maintenance of rural

power assets; (iii) providing centrally paid operators for subdistrict power stations; (iv) formulating a Government policy on a subsidy regime for the power assets

placed in the poorest communities; and (v) actively participating in the recovery of the Project.

81. Compliance, which will be discussed in biannual CSP review missions, also should be addressed during policy discussions about ADB’s future assistance for infrastructure projects. A second stage provision for power rehabilitation or expansion is not in place. However, the following considerations are relevant:

(i) A comprehensive study on sustainability measures for community-based rural power systems will be included in the imminent World Bank-administered National Rural Electrification Plan.

(ii) The successes of the rural communities operating without subsidies should be used as a “good practice” model for the rest of the country.

16 Appendix 1

PROJECT FRAMEWORK

Design Summary

Performance Indicators/Targets

Results

Monitoring Mechanisms

Assumptions and Risks

Goal Enable transport and power infrastructure to allow access to humanitarian assistance, health care, and water supply.

1. Repair main roads to

facilitate humanitarian assistance to population centers.

2. Ensure road sector

viability to induce revival of economic activity.

3. Urgently reduce port

congestion to enable effective and economical logistics for humanitarian goods.

4. Reinstate power

supply to revive basic services in communities.

5. Employ local labor

and skills to initiate income generation for local population.

Repaired. Achieved. Extension of the wharf missed the peak of port traffic in 2001. Achieved. Local labor employed, and income generated.

• Project

management • Consultations with

communities and authorities.

• Timely

implementation of the Project.

• Organization of

local employment.

• Identification of

adequate number and quality of East Timorese staff for localization programs.

Purpose 1. Emergency road repair. 2. Expansion and restoration of port facilities.

1.a. Restore viable road conditions on all main arteries. 1.b. Establish essential equipment for empowering local contracting industry. 1.c. Construct essential causeways and bridges where no access is otherwise provided. 1.d. Establish contracts. 2.a. Expanded port facilities. 2.b. Improved cargo

Restored. Established. Constructed. Established. Third berth added. Improved.

• Periodic project

reports. • Project review

missions. • Tripartite

meetings.

• Expedite

contracting arrangements.

• Availability of

funding from the Trust Fund for East Timor (TFET).

• Effective project

implementation.

Appendix 1 17

Design Summary

Performance Indicators/Targets

Results

Monitoring Mechanisms

Assumptions and Risks

3. Restoration of power supply. 4. Establish employment programs.

handling capacity. 3. Power station rehabilitation. 4. Local contracts for unskilled and skilled labor.

District and subdistrict power stations were rehabilitated. Contracts were provided.

Outputs 1. Emergency road repair. 2. Emergency port rehabilitation. 3. Reinstatement of power supply.

1.a. Emergency road repair of main arteries. 1.b. Equipment for inducing contracting industry. 1.c. Labor-based causeway construction, and bailey bridges 2.a. Wharf extension at the Dili Port. 2.b. Restoration of the landing craft slipway at Dili port. 2.c. Upgrading of container yard at Dili Port. 2.d. Beach matting at Beacu, Betano, and Suai. 2.e. A heavy forklift for containers at Dili port. 3.a. 15 power stations rehabilitated. 3.b. Distribution line rehabilitated. 3.c. Tools, instruments, equipment, radio, and

Road was repaired in a timely fashion. Equipment was provided. Labor-based construction was implemented. Wharf extension was completed. Slipway was rehabilitated. Eastern yard was upgraded. Beach matting component was canceled. A heavy forklift was canceled. 18 power stations rehabilitated. Associated distribution line rehabilitated. Installed.

• Designs. • Civil works

contracts. • Road network

performance indicators.

• Review meetings

and missions. • Periodic project

reports.

• Availability of

TFET funding.

18 Appendix 1

Design Summary

Performance Indicators/Targets

Results

Monitoring Mechanisms

Assumptions and Risks

repeater system installed. 3.d. Comoro power station high-voltage switchgear replaced. 3.e. Utility financial management developed.

Canceled and transferred to the Government of Japan. About 60% completed

Inputs 1. International and local consultant services. 2. Civil works.

1. Selection of international and local consultant services for project management by May 2000 ($1.4 million). 2. Issue and implement civil works road repair contracts by 15 May 2000 ($2.5 million), by 31 December 2000 ($3.2 million), and by 15 December 2002 ($14.8 million). 3. Implement port rehabilitation civil works contracts by 15 May 2000 ($0.7 million) and by 31 December 2000 ($1.4 million). 4. Implement power rehabilitation civil works contracts by 15 May 2000 ($1.0 million), by 31 December 2000 ($1.3 million), and by 15 December 2002 ($0.5 million).

Consultants selected and services rendered throughout project implementation ($2.3 million). Civil works contracts issued for roads and implemented starting May 2000 ($20.7 million). Port rehabilitation contracts issued and implemented starting June 2000 ($1.2 million). Power rehabilitation implemented from September 2000 ($5.5 million).

• Project reports.

• Timely

deployment of competent consultants.

• Timely tender

process.

Appendix 2 19

STATUS OF COMPLIANCE WITH GRANT COVENANTS

Condition/Covenant

Reference in Grant

Agreement

Status of

Compliance 1. The recipient declares its commitment to the

objectives of the Project as set forth in Schedule 2 to this Agreement; and, to this end, shall carry out the Project through the project management unit with due diligence and efficiency and in conformity with appropriate administrative, engineering, environmental, financial, and social practices; and shall provide promptly, as needed, the funds, facilities, services, and other resources required for the Project.

Section 3.01 (a)

Complied with.

2. Without limitation upon the provisions of paragraph (a) of this Section, and except as the recipient and ADB shall otherwise agree, the recipient shall cause the Project to be carried out in accordance with the implementation arrangements set forth in Schedule 4 to this Agreement.

Section 3.01 (b)

Complied with.

3. Except as ADB shall otherwise agree, procurement of the goods, works, and consultants’ services required for the Project and to be financed out of the proceeds of the grant shall be governed by the provisions of Schedule 3 to this Agreement.

Section 3.02

Complied with.

4. The recipient shall maintain, or cause to be maintained, records and accounts adequate to reflect in accordance with sound accounting practices the operations, resources, and expenditures for the Project of the departments or agencies of the recipient responsible for carrying out the Project or any part thereof.

Section 4.01 (a) Complied with.

(iii) furnish to ADB such other information concerning said records and accounts, and the audit thereof, as ADB shall from time to time reasonably request.

5. For all expenditures with respect to which withdrawals from the grant account were made on the basis of statements of expenditure, the recipient shall: (i) maintain, or cause to be maintained, in

accordance with paragraph (a) of this Section, records and accounts reflecting such expenditures;

Section 4.01 (c) Complied with.

20 Appendix 2

Condition/Covenant

Reference in Grant

Agreement

Status of

Compliance (ii) retain, until at least 1 year after ADB has

received the audit report for the fiscal year in which the last withdrawal from the grant account was made, all records (contracts, orders, invoices, bills, receipts, and other documents) evidencing such expenditures;

(iii) enable ADB’s representatives to examine such records as ADB shall from time to time reasonably request; and

(iv) ensure that such records and accounts are included in the annual audit referred to in paragraph (b) of this Section, and that the report of such audit contains a separate opinion by said auditors as to whether the statements of expenditure submitted during such fiscal year, together with the procedures and internal controls involved in their preparation, can be relied upon to support the related withdrawals.

6. Except as ADB may otherwise agree, the procedures and qualifications referred to in the following provisions of Section I of this Schedule shall apply in the procurement of goods and works to be financed out of the proceeds of the grant.

Schedule 3, para. 1

Complied with.

7. The recipient may use the proceeds of the grant only for procurement of goods and works supplied from, and procured in, (i) member countries of ADB, (ii) East Timor, (iii) countries that have entered into a contribution agreement with the trustee with respect to the TFET, and (iv) countries that are members of any organization that has entered into a contribution agreement with the trustee with respect to the TFET.

Schedule 3, para. 2

Complied with.

8. Subject to the qualification stated in the preceding paragraph, procurement of goods and works shall be subject to the provisions of the Guidelines for Procurement under Asian Development Bank Loans dated February 1999 (hereinafter called the Guidelines for Procurement), as amended from time to time, and the following provisions of Section I of this Schedule.

Schedule 3, para. 3

Complied with.

Appendix 2 21

Condition/Covenant

Reference in Grant

Agreement

Status of

Compliance 9. Each civil works contract estimated to cost the

equivalent of more than $1 million, and each supply contract for equipment or materials estimated to cost the equivalent of more than $500,000, shall be awarded based on international competitive bidding, as described in chapter II of the Guidelines of Procurement.

Schedule 3, para. 4

Complied with.

10. Bidders for civil works contracts shall be prequalified before bidding.

11. Each civil works contract estimated to cost the equivalent of $1 million or less, and each supply contract for equipment or materials estimated to cost the equivalent of $500,000 or less (other than minor items), shall be awarded based on international shopping, as described in Chapter III of the Guidelines for Procurement.

Schedule 3, para. 5

Complied with.

12. Goods estimated to cost less than the equivalent of $100,000 per contract may generally be procured based on direct purchase and/or negotiation, or single tender, in accordance with the provisions of paragraph 3.05 of the Guidelines for Procurement.

Schedule 3, para. 6

Complied with.

13. Notwithstanding the provisions of paragraph 5, small works contracts (defined as any civil works contract estimated to cost the equivalent of $100,000 or less), at the discretion of ADB, may be procured under lump-sum, fixed-price contracts awarded based on local competitive bidding among prequalified contractors. Any such procurement shall be in accordance with procurement procedures acceptable to ADB, with prequalification, selection, and engagement of contractors being subject to the approval of ADB. Without limiting the generality of the foregoing, whenever local competitive bidding is approved, quotations shall be obtained from three qualified contractors in response to a written invitation. The invitation shall include a detailed description of the works, including basic specifications, the required completion date, a basic form of agreement acceptable to ADB, and relevant drawings, where applicable. The award shall be made to the contractor who offers the lowest price quotation for the required work, and who has the experience and resources to complete the contract successfully.

Schedule 3, para. 7

Complied with.

22 Appendix 2

Condition/Covenant

Reference in Grant

Agreement

Status of

Compliance 14. Works required for the Project involving

community participation may be procured in accordance with procedures acceptable to ADB.

Schedule 3, para. 8

Complied with.

Complied with. 15. Before the issuance of any invitations to prequalify for bidding or to bid for contracts, the Project management unit shall furnish ADB with a proposed procurement plan for the Project for its review and approval. Procurement of all goods and works shall be undertaken in accordance with such procurement approved by ADB.

Schedule 3, para. 9

16. With respect to each contract awarded on based on international competitive bidding, procurement actions shall be subject to review by ADB in accordance with the procedures set forth in Chapter IV of the Guidelines for Procurement. Each draft prequalification invitation and each draft invitation to bid, to be submitted to ADB for approval under such procedures, shall reach ADB as far as possible before it is to be issued, and shall contain such information as ADB shall reasonably request to enable ADB to arrange for the separate publication of such invitation.

Schedule 3, para. 10 (a)

Complied with.

17. For all other contracts, each draft invitation to bid and related bid document shall be submitted to ADB for approval before they are issued.

Schedule 3, para. 10 (b)

Complied with.

18. Each award of contract shall be subject to prior ADB approval.

Schedule 3, para. 10 (c)

Complied with.

19. The services of consultants shall be used to carry out the Project, particularly for staffing of the Project management unit.

Schedule 3, para. 11 (a)

Complied with.

20. Five international consultants shall be recruited: (i) a chief technical adviser, (ii) a financial manager, (iii) a roads engineer, (iv) a ports engineer, and (v) an electrical engineer.

Schedule 3, para. 11 (b)

Complied with.

21. In addition, five East Timorese nationals shall be recruited: (i) a project manager, (ii) a project accountant, (iii) a roads engineer, (iv) a port engineer, and (v) an electrical engineer.

Schedule 3, para. 11 (c)

Complied with.

22. The terls of reference of the consultants shall be as prepared by ADB and agreed with the recipient.

Schedule 3, para. 11 (d)

Complied with.

23. The consultants shall be nationals of (i) any of the member countries of ADB, (ii) East Timor, (iii) countries that have entered into a contribution

Schedule 3, para. 12

Complied with.

agreement with the trustee with respect to the

Appendix 2 23

Condition/Covenant

Reference in Grant

Agreement

Status of

Compliance TFET, and (iv) countries that are members of any organization that has entered into a contribution agreement with the trustee with respect to the TFET.

24. Subject to the qualification stated in the foregoing paragraph, the selection, engagement, and services of the consultants shall be subject to the provisions of the Guidelines on the Use of Consultants by Asian Development Bank and Its Borrowers, dated October 1998, as amended from time to time, and the following provisions of Section II of this Schedule.

Schedule 3, para. 13