Acute Pericarditis and Pericardial Effusion Meghan York October 15, 2008.

Asbestos induced pericardial effusion and …strictive pericarditis, andthreecasesare reported here....

Transcript of Asbestos induced pericardial effusion and …strictive pericarditis, andthreecasesare reported here....

-

429Thorax 1991;46:429-432

Asbestos induced pericardial effusion andconstrictive pericarditis

D Davies, M I J Andrews, J S P Jones

City Hospital,Nottingham NG5 1PBD DaviesJ S P JonesSt Mary's Hospital,Portsmouth P03 6ADM I J AndrewsReprint requests to:Professor JonesAccepted 21 February 1991

AbstractThe number of disorders attributable toasbestos exposure has increasedgradually over the years. The latest to berecorded is pericardial effusion and con-strictive pericarditis, and three cases arereported here. A man with bilateralpleural thickening and plaquesdeveloped acute pericarditis and aneffusion and was treated by pericardi-ectomy. Two men died from constrictivepericarditis associated with bilateralpleural effusions and diffuse pleural thick-ening. The pericardium showed non-specific fibrous thickening. All had beenoccupationally exposed to asbestos. Inthe fatal cases the lungs containedamphibole fibres, in keeping with amodest degree of occupational exposure.Asbestos produces progressive fibrosis ofthe pericardium that is similar to diffusepleural thickening and may be fatal.Both conditions may develop afterrelatively short or light exposure.

The association between asbestos exposureand diffuse lung fibrosis was established by1930 but the recognition of other disorderscaused by asbestos came slowly. The associa-tion with lung cancer was recognised by 1955and with mesothelioma in 1960. At about thesame time the association between asbestosexposure and hyaline pleural plaques was de-scribed'2 and soon afterwards asbestosinduced pleural effusions were reported,3 someof which cleared while others left considerablepleural thickening. Diffuse pleural thickeningwithout preceding effusions45 was recognisedand bilateral diffuse pleural thickening becamea prescribed disease in 1985. Another variantis visceral pleural plaque formation; this tendsto cause rounded atelectasis, which mimics atumour.6

Calcified plaques are sometimes seen on theheart border. Nearly all are in the mediastinalpleura, though occasional plaques occur inthe parietal pericardium.7 A few asbestosassociated primary mesotheliomas of thepericardium have been reported.89 Pleuralmesotheliomas often invade the pericardiumand may cause constrictive pericarditis. Twocases of asbestos associated non-malignantconstrictive pericarditis have been pub-lished.'°0 We present a further three.

Case reportsPATIENT IIn November 1983 a man of 43 was admitted tohospital with precordial pain of 12 hours'duration. No abnormality was found by clinicalexamination but he had neutrophilia and araised erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Theelectrocardiogram showed changes of acutepericarditis. Serial cardiac enzymes were nor-Mal. Radiographs showed diffuse bilateral

~~~~pleural thickening, calcified plaques, and anormal heart shadow. The pain eased and hewas discharged after three days with a diagnosisof pericarditis of undetermined cause.

Fresh precordial pain led to his readmission amonth later. He was febrile, the venous pres-sure in the neck was 3 cm and he had apericardial rub. The chest radiograph showedan enlarged cardiac shadow and--unchangedpleural shadowing (fig 1). Echocardiographyshowed a moderate effusion.The tuberculin skin test and blood culture

gave negative results. Concentrations ofcardiac enzymes, serum electrolytes, glucose,and complement were normal. Autoantibodiesand antibodies against viruses, psittacosis, andcoxiella were not found. The antistreptolysin

Figure I Chest radiograph from case 1 showing an enlarged cardiac shadow, calcified titre was normal and viruses were not isolatedplaques and diffuse bilateral pleural thickening. from throat swabs or stools.

on May 21, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://thorax.bm

j.com/

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.46.6.429 on 1 June 1991. D

ownloaded from

http://thorax.bmj.com/

-

Davies, Andrews, Jones

A thoracotomy was carried out. Pleuralplaques were present in the parietal layer of thelower chest wall and diaphragm. There wasalso diffuse fibrous thickening ofthe pleura andpericardium. A partial pericardiectomy wascarried out.

Histologically the pleural plaques showedcharacteristic bundles of collagen arranged in a"basket weave" pattern. The thickenedpericardium and pleura showed a similarbasket weave pattern with hyalinisation andmoderate lymphocytic infiltration. In addition,the pericardium showed a fibrinous exudate onits surface (fig 2). Examination of the veryscanty peripheral fragments of lung tissue thatwere adherent to the thickened pleura showedoccasional asbestos bodies of classicalappearance but no asbestosis. The patientmade a good recovery and there has been noprogression of the pleural thickening.Occupational history Heavy exposure toasbestos of unknown type had occurred fromthe age of 18 to 20, when he worked as a lagger.

PATIENT 2In 1982 a man aged 64 years complained ofdizziness and was found to be hypertensive. Noother abnormality was detected and anelectrocardiogram was normal. A chestradiograph showed calcified plaques on bothdiaphragms. His blood pressure was controlledwith hydrochlorothiazide and triamterene.

In January 1984 he developed chest tight-ness, a dry cough, and shortness of breath.When seen in hospital he had tachycardia,slightly enlarged liver and normal blood pres-sure. An electrocardiogram showed low voltageand T wave inversion in leads 1, 2, 3, AVF, andV 4-6. The chest radiograph showed a largeheart and clear lung fields. Liver function testsgave abnormal results. He was considered tohave had a myocardial infarction with secon-

Figure 2 Microscopicappearance of the visceralpericardium (case 1)showing hyalinised "basketweave" thickening, with azone of lymphocytesadjacent to themyocardium and afibrinous exudate on thesurface.

dary congestion ofthe liver. Hypotensive drugswere discontinued.He was readmitted to hospital in June 1984

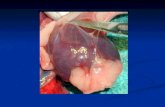

because of increased shortness of breath. Hehad distended neck veins, a large liver, oedemaup to the thighs, and a large right pleuraleffusion. An echocardiogram was considered toshow congestive cardiomyopathy. Aspirationofthe pleural effusion produced 2 litres of strawcoloured pleural fluid, which formed a clotcontaining lymphocytes and mesothelial cells.The oedema decreased with diuretic treatment.Over the next year he remained short of breathbut with little oedema. In 1985 he became moreoedematous and the liver was enlarged to 5 cmdespite large doses of diuretics. In October hehad gross oedema, distended neck veins, andbilateral pleural rubs. A chest radiographshowed a large effusion on the right and amoderate effusion on the left. Repeated aspira-tions ofthe effusion on the right produced bloodstained fluid with a high protein content con-taining red cells, lymphocytes, and a fewmesothelial cells. Pleural biopsy specimensshowed dense fibrous tissue only. He continuedto deteriorate, with increased shortness ofbreath, gross neck vein distension, and largebilateral pleural effusions, and he died inJanuary 1986.Necropsy showed a rigid, constrictive

pericardium resulting from dense hyalinethickening of both visceral and parietal layers(fig 3). The former was up to 0-2 cm in diameterand the latter up to 0 5 cm. Microscopically,the pericardium varied from acellular collagen-ous areas to cellular fibroblastic tissue accom-panied by a non-specific inflammatory reaction(fig 4). Fibrin was present on the surface. Noevidence of neoplasm was seen. The pleuralcavities contained 800 ml of blood stainedeffusion on the right side and a similar 700 mleffusion on the left. Calcified hyalinised pleuralplaques were present on the diaphragmaticpleurae of both sides. The right lung showed

Figure 3 Hyaline thickening of visceral and parietallayers ofpericardium, which have become partially fusedtogether (case 2).

430

on May 21, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://thorax.bm

j.com/

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.46.6.429 on 1 June 1991. D

ownloaded from

http://thorax.bmj.com/

-

Asbestos induced pericardial effusion and constrictive pericarditis

Figure 4 Microscopicappearance of thethickened pericaridum(case 2) showingcollagenous bundles ofvarying cellularity.Myocardialfibres at loweredge ofphotograph.

Figure 5 Diffuse fibrousthickening of visceralpleura (case 2).

diffuse thickening of the visceral pleura up to0-2 cm in diameter (fig 5). The parietal pleurashowed hyaline thickening up to 1 cm. The leftlung showed a lesser degree of diffuse fibrousthickening and a fibrinous deposit on the vis-ceral pleural surface. No evidence of pleuralneoplasm was present and the microscopicappearances were similar to those of thepericardium. Microscopic examination of the

lung tissue showed a minor degree of asbestosiswith patchy interstitial fibrosis, and asbestosbodies ofclassical appearance. Mineral analysisof lung tissue at the Medical Research Councilunit at Penarth, using electron microscopy andenergy dispersive x ray analysis, showed 3-6million fibres ofcrocidolite and 22 million fibresof amosite per gram of dry lung.Occupational history In his youth this patienthad served in the Merchant Navy and at theend of the war he became a marine engine fitter,working in a naval dockyard. He had beenexposed to asbestos intermittently over manyyears until his retirement in 1982.

PATIENT 3In July 1976 a man aged 43 years complainedof weight loss and shortness of breath.Radiographs showed extensive pleural thicken-ing over the periphery and base of the rightlung and a large left pleural effusion, which wasfound to be blood stained. He remained unwelland short of breath. He gradually developedsigns of right heart failure and the amount ofpleural shadowing increased on both sides. Hedied from heart failure in 1980 at the age of 47years.Necropsy showed severe pericardial restric-

tion with fusion of the visceral and parietallayers to form a diffuse dense fibrous encap-sulation of the heart up to 0 9 cm across. Thepleurashoweddiffuse fibrous thickening consis-ting of white compact hyalinised connectivetissue up to 4 cm in diameter. In places thevisceral and parietal layers of the pleura werefused, while in others a haemorrhagic effusionwas present in the pleural space. Micro-scopically the pericardial and pleural tissueswere of similar appearance, showing densehyaline thickening of acellular collagenousmaterial (fig 6). Capillary blood vessels werepresent, but there was no evidence of activeinflammation. No neoplasm was present. Thelung tissue showed no evidence of asbestosis-that is, no generalised fibrosis and only scantyasbestos bodies were detected by light micro-scopy. Mineral analysis ofthe lung tissue by theMRC Unit, Penarth, using electron micro-scopy and energy dispersive x ray analysis'2showed: 2-5 million fibres of crocidolite, 0 9million fibres ofamosite, and 14-2 million fibresof chrysolite per gram of dry lung.Occupational history In 1963 and 1964 thepatient worked alongside a man who mixed anasbestos compound while casting lead grids. In1971 he spent several months making carbatteries. For this he melted bitumen in a largemixer and tipped in bags of asbestos and mica,which were then stirred in. The mixture wasthen poured into moulds.

DiscussionThe three men had been occupationallyexposed to asbestos, but by comparison withlife long insulation workers, for example, theirexposure was not heavy. The asbestos contentof the lungs in two of the cases is in keepingwith a relatively modest degree of occupationalexposure to amphibole fibres. Patient 1 had

431

on May 21, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://thorax.bm

j.com/

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.46.6.429 on 1 June 1991. D

ownloaded from

http://thorax.bmj.com/

-

Davies, Andrews, Jones

Figure 6 Acellular collagen showing "basket weave" pattern on pleural surface, withidentical appearance on pericardial surface (case 3).

heavy exposure for two years to asbestos ofunknown type. The exposure in patient 2 wasspread over 25 years or more, but it wasprobably very intermittent. Patient 3 had fairlylight exposure for about two years and heavyexposure for less than a year, the latter almostcertainly to crocidolite. It is well recognisedthat relatively light exposures to amphiboleasbestos may produce benign pleural fibrosis.'3Asbestosis requires heavier exposures.

All three patients had asbestos inducedpleural effusions and diffuse pleural fibrosis.Patient 1 developed acute pericarditis super-imposed on bilateral diffuse pleural thickeningof unknown duration, which had not changedduring five years of subsequent observation.The pericardial effusion appeared 23 years afterhis last exposure to asbestos. This is muchlonger than the usual interval for asbestosinduced pleural effusions. The pericarditisbecame fibrinous, and considerable fibrousthickening developed over six weeks. He wouldprobably have developed progressive constric-tive pericarditis but for the pericardiectomy.We believe that patient 2 began with a

pericardial effusion, and the only precedingasbestos related condition was parietal pleuralplaques. The fluid decreased quickly and hedeveloped a unilateral pleural effusion some fivemonths later. The extensive oedema and livercongestion at that time indicates that thepericardial constriction was well advanced.Bilateral pleural effusions developed 10 monthsafter the onset of illness and persisted until thepatient died from constrictive pericardialdisease. The minor degree of asbestosis foundat necropsy did not contribute materially to his

death. The interval from first exposure toasbestos to the development of pericardial andpleural effusions was again long-almost 40years-but the interval after hig-4at exposurewas probably fairly short. The time sequence incase 3 is less clear. The patient had establisheddiffuse pleural thickening on the right side at thetime when the left pleural effusion was detected.Whether he ever had a pericardial effusion orwhether the pericardial thickening developedon its own is unknown. Probably an effusion waspresent at some stage. The interval between thelast asbestos exposure and the onset of thepleural effusion was fairly typical at five years.

It has been suggested that the structureslining the body cavities-pleura, peritoneum,pericardium, and tunica vaginalis testis-havean identical disease pattern in response tocommon causative agents. " Asbestos inducedmalignant mesothelioma is such an example.These three cases of diffuse pericardial fibrosis,arising in patients who had been exposed toasbestos, are presented in support of this thesis.They illustrate the way in which the peri-cardium has produced a pathological responseidentical to that of the pleura.

We thank Mr W E Morgan for permission to publish the detailsabout patient 1 and Dr D Colin-Jones for the details aboutpatient 2; Dr T C Williams and Dr R M Whittington, HMCoroner, for permission to publish the details about patient 3;Professor F D Pooley, Dr A R Gibbs, and Mr D M Griffiths forthe mineral analyses; Mr Keith Miller for his technical expertise,and Mrs Valerie Bolton for the preparation of the manuscript.

1 Kiviluoto R. Pleural calcification as a roentgenologic sign ofnon-occupational evidence of anthophyllite asbestosis.Acta Radiol 1960;194(suppl):1-67.

2 Meurman L. Asbestos bodies and pleural plaques in aFinnish series of autopsy cases. Acta Pathol MicrobiolImmunol Scand 1966;suppl 181.

3 Eisenstadt NB. Asbestos pleurisy. Dis Chest 1964;46:78-81.4 Sheers, G, Templeton AR. Effects of asbestos in dockyard

workers. Br Med J 1968;3:574-9.5 Wright PH, Hanson A, Kreel L, Capel LH. Respiratory

function changes after asbestos pleurisy. Thorax 1980;35:31-6.

6 Mintzer RA, Gore RM, Vogelzang RL, et al. Roundedatelectasis and its association with asbestos-inducedpleural disease. Radiology 1981;139:567-70.

7 Fletcher DE, Edge JR. The early radiological changes inpulmonary and pleural asbestosis. Clin Radiol 1970;21:*355-65.

8 Kahn EI, Rohl A, Barrett EW, Suzuki Y. Primary peri-cardial mesothelioma following exposure to asbestos.Environ Res 1980;23:270-81.

9 Beck B, Konetze G, Ludwig V, Rothig W, Sturm W.Malignant pericardial mesothelioma and asbestosexposure: a case report. Am J Ind Med 1982;3:149-59.

10 Fischbein L, Namade M, Sachs RN, Robineau M,Lanfranchi J. Chronic Constrictive Pericarditis associatedwith asbestosis. Chest 1988;94:646-7.

11 Pope AR, Sokolowski JW, Spirn I. Constrictive pericarditis.Chest 1989;95:1172.

12 Pooley FD, Clark NJ. A comparison of fibre dimensions inchrysotile, crocidolite and amosite particles from samplesof airbome dust and from post-mortem lung tissuespecimens. In: Wagner JC, ed. Biological effects of mineralfibres. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer,1980:79-86. (IARC scientific publications No 30;INSERM symposia series Vol 92.)

13 Stephens M, Gibbs AR, Pooley FD, Wagner JC. Asbestosinduced diffuse pleural fibrosis. Thorax 1987;42:583-8.

14 Jones JSP. Pathology of the mesothelium. Berlin: Springer,1987:237-43.

432

on May 21, 2020 by guest. P

rotected by copyright.http://thorax.bm

j.com/

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.46.6.429 on 1 June 1991. D

ownloaded from

http://thorax.bmj.com/