arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I....

Transcript of arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I....

![Page 1: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/1.jpg)

Nonlinear optical conductivity of a generic two band systems, with application todoped and gapped graphene

Ashutosh Singh,1 Tuhina Satpati,1 Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh,1 and Amit Agarwal1, ∗

1Department of Physics, Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur, Kanpur - 208016, India2Department of Physics and Astronomy, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA

(Dated: June 17, 2016)

We present a general formulation to calculate the dynamic optical conductivity, beyond the linearresponse regime, of any electronic system whose quasiparticle dispersion is described by a two bandmodel. Our phenomenological model is based on the optical Bloch equations. In the steady stateregime it yields an analytic solution for the population inversion and the interband coherence,which are nonlinear in the optical field intensity, including finite doping and temperature effects.We explicitly show that the optical nonlinearities are controlled by a single dimensionless parameterwhich is directly proportional to the incident field strength and inversely proportional to the opticalfrequency. This identification leads to a unified way to study the dynamical conductivity andthe differential transmission spectrum across a wide range of optical frequencies, and optical fieldstrength. We use our formalism to analytically calculate the nonlinear optical conductivity of dopedand gapped graphene, deriving the well known universal ac conductivity of σ0 = e2/4~ in thelinear response regime of low optical intensities (or equivalently high frequencies) and non-lineardeviations from it which appear at high laser intensities (or low frequencies) including the impactof finite doping and band-gap opening.

I. INTRODUCTION

Since it’s discovery, graphene, a truly two-dimensionalsystem, has been at the forefront of material research [1–3]. On account of its linear dispersion and high carriermobility, graphene has demonstrated remarkable elec-tronic and optical properties [4]. In the linear responseregime, with weak optical field induced momentum lin-early coupling to the charge carriers in graphene, spec-tacular physical effects have been predicted and observedwhich are significantly enhanced or peculiar, when com-pared to their bulk counterparts. An early such surprisewas the observation of a strong coupling of a single mono-layer of carbon atoms to electro-magnetic radiation withalmost a constant absorption coefficient of 2.3% over abroad range of optical frequencies. The correspondingoptical conductivity is elegantly expressed in terms ofuniversal constants, in the form σ(ω) = σ0 ≡ e2/4~ [5–9]. Several exotic predictions and observations followed,including ultra-high mobility in pristine graphene [10],Klein tunneling [11], weak localization [12] and quantumhall effect [2, 13, and 14].

Following the first prediction of universal optical con-ductivity for graphite honeycomb lattices [15], severaltheoretical works extended the formulation to grapheneusing the Dirac cone approximation for clean samples[16–18], and with disorder [19]. Experimental observa-tion of the universal optical conductivity [5–9] gave astrong impetus to the field and motivated further theo-retical work. These include studying the bandstructureeffects on optical conductivity beyond the Dirac cone ap-proximation [20], analyzing effect of strain [21], role ofsubstrate [22] and the effect of electron-electron interac-tions on the optical conductivity [23–26]. In addition tothe linear conductivity, several remarkable non-linear op-tical effects in graphene have also been explored [22, 27–

36], motivating a plethora of applications[37–41] basedon broadband nonlinear optical properties of graphene.

In particular, non-linear optical response along withlinear dispersion in graphene imply higher harmonic gen-erations, and the large velocities of carriers results inhighly efficient electron-photon coupling. Furthermore,gapless excitation leads to effective resonant non-linearexcitation in graphene. These interesting possibilitieshave motivated a plethora of studies based on non-linearresponse of these 2-d materials, ranging from microwave[17], terahertz [42] to optical frequencies [37]. Such re-sponse has led to second and third harmonics genera-tion in the optical [43 and 44] and THz domain [45], fre-quency mixing ranging from microwave to optical excita-tions [46 and 47], self-phase modulation and optical Kerreffects [48 and 49], photon drag [50], THz driven chiraledge photo-currents [51] or, dynamic Hall-effect drivenby circularly polarized optical frequencies [52]. Such un-usual effects triggered a range of applications includinggraphene based rf modulators [53], optically gated tran-sistors [54 and 55], photo-detectors [56], graphene sat-urable absorbers for mode-locking [57] and even proposalfor nonlinear interaction at the level of single photons[58].

At a fundamental level, non-linear response functionsserve as excellent tools for probing intrinsic materialproperties. This provides a rich class of informationon material symmetry and selection rules, intricacies ofband-structure, electron-spin relaxation and decoherencemechanisms that are otherwise hidden in the linear re-sponse regime. There is thus significant motivation todevelop a unified theoretical framework to address non-linear response of low dimensional systems in general,that is applicable over a range of optical excitation fre-quencies, and a wide range of the incident optical fieldstrength.

arX

iv:1

606.

0507

2v1

[co

nd-m

at.m

es-h

all]

16

Jun

2016

![Page 2: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/2.jpg)

2

12 13 14 15log10(!)

2

4

6

8

log

10(E

0)

Non-linear cleanNon-linear

dirty

Linear dirty

Linear clean

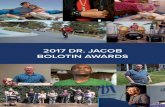

FIG. 1. Classification of different optical response regimesin the parameter space of optical frequency (in Hz) andthe incident radiation field strenth (in units of V/m). Thevertical black line marks the ω = γ2 boundary betweenthe dirty or low frequency (left) and the clean or high fre-quency (right) limits. The black dashed line marks the

ζ ≡ evFE0/(~ω√γ1γ2) = 1 line which is the boundary of the

linear (bottom) and non-linear (top) response regimes. Notethat for a given frequency and material (with fixed damp-ing parameters) the linear to non-linear regime crossover oc-curs at smaller field strength. Here we have chosen vF = 106

m/s, and γ1, γ2 = 1012, 1014 Hz, based on parameters forgraphene (see Ref. [27] and the references therein).

Motivated by Mishchenko [29], in this article wepresent a theoretical framework for calculating non-linearoptical conductivity of a general two-band system, whichis applicable over a large range of optical frequencies andfield strengths. We recast the wave-function based ap-proach of Ref. [29], into a density matrix based approachand this allows us to incorporate the impact of finite tem-perature, finite doping (chemical potential) etc. into thenon-linear conductivity calculations. In particular, weprovide steady state solutions for the coupled Maxwell-Bloch equations for a two band system, in which weinclude electron-electron and electron-phonon scatteringphenomenologically via the inter-band population inver-sion decay rate γ1 and the coherence decay rate γ2. Thesteady state population inversion and the inter-band co-herence is then used to calculate the optical conductivityfor a generic two band systems, and the optical transmis-sion spectrum for a two dimensional system in general.We apply the developed formulation to analyze the non-linear optical conductivity of doped and gapped graphenein detail. However, the formalism can also be applied toother systems such as bilayer graphene, Weyl semimetals,phosphorene etc. whose low energy electronic propertiesare captured by a two band model.

A natural outcome of our formalism is that, with γ1

and γ2 as two phenomenological input parameters, it al-lows us to classify the parameter space in terms of theincident optical frequency (ω) and field strength (E0)in four regimes: a) linear response in the clean regime,b) linear response in the dirty regime, c) non-linear re-

sponse in the clean regime and finally d) the non-linearresponse in the dirty regime [see Fig. 1]. What we callthe clean (dirty) regime can also be called the collision-less or high frequency limit (collisional or low frequency),and is quantified by the region ω ≥ γ2 (ω γ2).

The linear (ζ < 1) or nonlinear (ζ > 1) response of thesystem is quantified by a single dimensionless parameter[29],

ζ ≡ evFE0

~ω√γ1γ2, (1)

where vF denotes a material dependent effective veloc-ity. Non-linear optical effects start becoming dominanteither on increasing the field strength keeping the fre-quency constant, or alternatively by decreasing the fre-quency while keeping the field strength constant.

The manuscript is organized as follows: in Sec. II, wedescribe a general two band systems and its optical re-sponse via the population inversion and coherence. Thisis followed by a discussion of the non-linear optical con-ductivity in Sec. III, and the differential transmission ofa freestanding two dimensional material in Sec. IV. InSec. V and Sec. VI, we discuss the dynamic conductivityof doped and gapped graphene respectively, in variouslimiting cases of linear response in clean limit (previ-ously known), linear response in dirty limit, non-linearresponse in the clean limit and the most general case ofnon-linear response in the dirty limit. Finally we sum-marize our findings in Sec. VII.

II. POPULATION INVERSION ANDCOHERENCE IN A GENERAL TWO BAND

SYSTEM

We start with a very generic two band electronic sys-tem, in presence of an electromagnetic radiation. Theelectromagnetic field is treated classically in the coulombgauge, with the vector potential A satisfying ∇ ·A = 0and the scaler potential Φ = 0, yielding B = ∇×A andE = −∂tA. The Hamiltonian describing the dynamicsof an electron in presence of an external electromagnetic

field, is given by Hem = H0(~k→ ~k+eA), which is usu-ally approximated as Hem ≈ H0 + e~−1A · ∇kH0. Notethat while Hem is an approximation for general two bandsystems, it is exact for systems described by the two di-mensional Dirac Hamiltonian, for which H0 only dependslinearly on the wave-vectors. Furthermore, from the per-spective of calculating optical conductivity, this is akinto neglecting the diamagnetic part of the current (whichanyway vanishes for Dirac systems since ∂2H0/∂k

2i = 0),

and only focussing on the paramagnetic part of the re-sponse function [59].

In the eigen-basis of H0, the effective Hamiltonian,can be rewritten as, Hem = H ′0 + A ·M, where H ′0 isa diagonal matrix comprising of the dispersion of twobands. The elements of the matrix M are defined byMλλ′(k) = e~−1〈ψλ|∇kH0|ψλ

′〉. We consider light to

![Page 3: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/3.jpg)

3

be incident perpendicular to the sample, with negligi-ble transverse momentum, such that it does not signifi-cantly alter the electron momentum. This sets a selectionrule, allowing only vertical transitions in the momentumspace. More explicitly, Hem = H ′0 +HI , where we have

H ′0 =∑k

εckack†ack + εvka

vk†avk , (2)

with ack(ac†k ) and avk(av†k ) being the annihilation (cre-ation) operator for electron in the conduction and valanceband respectively. The interaction part of the Hamilto-nian is given by

HI

~=∑k

Ωcck ack†ack + Ωvvk a

vk†avk + Ωcvk a

ck†avk + Ωvck a

vk†ack,

(3)

where we have defined ~Ωλλ′

k = Mλλ′(k) · A to be theRabi frequencies.

Let us now consider an arbitrary two band system,whose low-energy quasiparticle bands are described bythe generic 2× 2 Hamiltonian,

H0 =∑k

hk · σ, (4)

where hk = (h0k, h1k, h2k, h3k) is a vector composedof real scalar elements and σ = (112, σx, σy, σz) is avector composed of the identity and the Pauli ma-trices in two dimensions. The eigen energies of H0

are given by ελk = h0k + λgk where we have de-

fined gk ≡√h2

1k + h22k + h2

3k, and λ = 1 (or −1)denotes the conduction (valance) band. The corre-sponding eigenvectors can be conveniently expressed asψλ = cos θλk, sin θλke

iφk, where tanφk = h2k/h1k,

and tan θλk = (λgk − h3k)/√h2

1k + h22k. Note that

for the special case of materials, such as graphene, forwhich h0k = h3k = 0, we have cos θλk = 1/

√2, and

sin θλk = λ/√

2.The optical matrix elements can accordingly be ob-

tained in a very general form, as follows

Mvv =e

~gk

(gk∇kh0k −

∑i=1,2,3

hik∇khik

), (5)

Mcc =e

~gk

(gk∇kh0k +

∑i=1,2,3

hik∇khik

), (6)

Mvc = − e

~gkhk

(− h2

k∇kh3k + (h1kh3k − ih2kgk)∇kh1k

+(h2kh3k + ih1kgk)∇kh2k

), (7)

Mcv = (Mvc)∗

(8)

where we have defined h2k ≡ h2

1k + h22k.

To describe the dynamics of the system, we considerthe time evolution of the momentum resolved density ma-trix (2 × 2), whose diagonal elements are ρ11 = ρvk, and

ρ22 = ρck. Here ρλk ≡ 〈aλk†aλk〉 denotes the momentum

resolved electron density in the valance and conductionbands. The off-diagonal elements of the density matrixare given by ρ12 = pk ≡ 〈ack

†avk〉, and ρ21 = p∗k, with pkdenoting the inter-band coherence or polarization. Us-ing the equation of motion, i~∂tρ(t) = [H, ρ], we ob-tain the following equation for the population inversion,nk ≡ ρck − ρvk, as

∂tnk = 4= [Ωvck (t)∗pk(t)] . (9)

The corresponding inter-band coherence evolves as

∂tpk = i [ωk + Ωcck (t)− Ωvvk (t)] pk(t)− iΩvck nk(t) , (10)

where ~ωk = εck − εvk.To obtain the steady state (long time average re-

sponse), we do a rotating wave approximation, where inwe get rid of the fast oscillating terms (with frequencies2ω and higher), and retain the slow time dependencein Eqs. (9) and (10). To this end, one can substituteA(t) = e0ω

−1E0 cosωt, with e0 denoting the polariza-tion direction. Keeping only the low frequency resonantterms (of the form of e±i(ω−ωk)), while neglecting all thehigh frequency ones (e±i(ω+ωk)) leads to:

∂tn = 2=[Ωvc∗k pk

], (11)

∂tpk = i(ωk − ω)pk − iΩvck nk/2 , (12)

where ~Ω = M · e0 E0/ω, pk(t) = pk(t)e−iωt, andnk = nk(t). Here p, and nk, are almost frozen (varyvery slowly) over the timescales of the order of 1/ω. Notethat Eqs. (11)-(12) do not include energy relaxation anddecoherence mechanisms, arising due to electron-electroninteractions, electron-phonon, electron-impurity scatter-ing and other interactions. To include these effects, phe-nomenological damping terms are added in the aboveequations [60] leading to

∂tnk = 2=[Ωvc∗k pk

]− γ1(nk − neq

k ) , (13)

∂tpk = i(ωk − ω)pk − iΩvck nk/2− γ2pk . (14)

Here γ1 is the inverse of the relaxation time for the mo-mentum resolved occupation number and γ2 is the inverserelaxation time of coherence. The equilibrium populationinversion in absence of the optical field is neq

k = fck−fvk.The function fak = [1 + exp ((εak − µ)/kBT )]−1 denotesthe Fermi function (kB and T are the Boltzmann con-stant and temperature, respectively). The relaxationrates γ1 and γ2 are usually dominated by electron-phononand electron-electron interactions, respectively. Gener-ally the damping rates are frequency dependent [29], andcan be modeled microscopically by self-consistently solv-ing electron-electron (generally at a mean field level),electron-phonon and electron-photon coupling equations[61]. For example in graphene, typical values of γ1 ≈ 1012

Hz, and γ2 ≈ 1014 Hz for optical frequencies [27]. How-ever, for simplicity of analysis, we choose these rates tobe constants over the frequency range considered in thiswork.

![Page 4: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/4.jpg)

4

In the steady state regime, we can solve Eqs. (13) and(14) to obtain the following steady state values for thepopulation inversion

nkneqk

=

(1 +

γ2|Ωvc|2

γ1[(ωk − ω)2 + γ22 ]

)−1

, (15)

and the inter-band coherence

pk =nk2

Ωvc

(ωk − ω) + iγ2. (16)

Before proceeding further it is instructive to express thesteady state population inversion of Eq. (15), in the fol-lowing form,

nkneqk

≡ G =

(1 +|Mvc · e0|2

e2v2F

ζ2 γ22

[(ωk − ω)2 + γ22 ]

)−1

,

(17)where ζ is specified by Eq. (1). In Eq. (17), Mvc·e0/(evF)is the dimensionless material dependent optical matrixelement component which couples to the incident ra-diation. The term γ2/[(ωk − ω)2 + γ2

2 ] in Eq. (17) isa Lorentzian centered around ω = ωk with half-widthγ2. It reduces to a Dirac-delta function δ(ω − ωk) inthe limiting case of γ2/ω → 0. Furthermore, we notethat G can be expanded in a power series of ζ2. Thusζ is a dimensionless effective field strength, which, fora fixed value of the optical frequency and the dampingconstants, distinguishes between the linear (ζ 1) andthe nonlinear (ζ ≥ 1) response regime [29]. Additionally,for a fixed value of the optical frequency and effectivefield strength, the ratio γ2/ω determines the clean/highfrequency (γ2 ω) or the dirty/low frequency limits(γ2 ≥ ω). This classification of the system’s responseinto linear and non-linear regimes, or alternatively intothe clean and the dirty limit arises naturally in our for-mulation and will be used in the rest of the manuscript.

Having obtained the steady state density matrix ele-ments, we now proceed to calculate the induced currentdensity and the nonlinear optical conductivity.

III. NONLINEAR INTER-BAND OPTICALCONDUCTIVITY

To obtain the inter-band contribution to the opti-cal current and optical conductivity, let us consider thegeneric form of the current density for a d-dimensionalsystem: J(t) = −gsgv(2π)−d

∫dk Jk(t), where gs (gv)

denotes the spin (valley) degeneracy factor, Jk(t) =eTr[ρk(t)vk(t)] and the generalized velocity operator isgiven by vk = −i~−1[r, H0] = ~−1∇kH0. The momen-tum dependent component of the particle current densityis then

Jk(t) = 2<e[pkMcvk ] +

∑λ=c,v

ρλkMλλ , (18)

(a) (b) (c)

(d) (e) (f)

FIG. 2. The momentum resolved current Jkx density ofEq. (20), in the kx − ky plane for graphene in panels a), b)and c) and for massive graphene in panels d), e), and f). Inpanels b) and c) [panels e)-f) for massive case] we have a largercoherence decay rate γ2 = ω/5 as compared to a) for whichγ2 = ω/20 and this show the impact of broadening of the cur-rent density around the circle k = ω/(2vF) at µ = 0. Furtherin panel c) for graphene [panel f) for massive graphene], wedisplay the impact of a finite chemical potential µ = 0.5~ωwhich manifests itself in the Pauli blocking of the momentumspace for k < µ/~vF. For more details see Eq. (43) for mass-less graphene, and Eq. (54) for the massive graphene case.

In presence of particle-hole symmetry, as in graphene orgapped graphene, we have Mcc

k = −Mvvk . One can then

rewrite Eq. (18) as

Jk(t) = 2<e[pk(t)Mcvk ] + nk(t)Mcc

k . (19)

It is evident that the first term in Eq. (19) arises from theinter-band contribution, while the second term originatesfrom the intra-band contributions. In Eq. (19), pk(t) =pke

iωt, and consequently the momentum resolved cur-rent density consists of three terms: 2<e [pkM

cvk ] cosωt,

−2=m [pkMcvk ] sinωt and nkM

cck . Of these, the term pro-

portional to cosωt is the out of phase (with respect tothe incident field) response of the system and it doesnot contribute to the dissipative part of the conductivity[29]. Hence it will be neglected in the rest of the arti-cle. Furthermore, for graphene and gapped graphene, itis easy to check that the intra-band term nkM

cck , van-

ishes on performing the momentum sum. In fact, sincewe have considered only momentum conserving verticaltransitions in calculating the electronic density matrix, itthen follows that the intra-band part of Eq. (18) shouldvanish for all materials after the k−integration.

One therefore needs to focus only on the dissipativepart of the current, which is captured by the in-phase(to the electric field) part of the response correspondingto the sin(ωt) term. This part of the momentum resolved

current, can be expressed as Jk(t) = Jk sin(ωt), with

Jk = −E0

~ωnk=m

(Mvc

k · e0)Mcvk

ωk − ω + iγ2

. (20)

![Page 5: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/5.jpg)

5

The corresponding dynamical nonlinear optical conduc-tivity can then be obtained by integrating the above ex-pression and using σij = |Ji|/[E0(e0 · j)], where E0(e0 · j)is amplitude of the field along the j direction.

If one considers a linearly polarized light, say alongthe x-direction, and restrict oneself to the longitudinalresponse only, then Eq. (20) reduces to

JkxE0

= − nk|Mvcx |2

~ω=m

1

ωk − ω + iγ2

. (21)

In Eq. (21), the total current, is in general ‘cut-off’ orband-width dependent. For systems described by a con-tinuum model, the ultraviolet momentum cutoff is in-versely proportional to the lattice spacing. On the con-trary, for systems described by a tight-binding model,the energy cutoff is typically the band-width of the sys-tem. Furthermore, there is static component of the cur-rent in the ω → 0 limit. This is unphysical, since inthis limit, the inter-band current must vanish for a time-independent vector potential. Accordingly, this contribu-tion needs to be subtracted from Eq. (21) as prescribedin Ref. [62].

The momentum resolved current density of Eq. (21) isshown in Fig. 2 for graphene and massive graphene.

Using Eq. (21), the longitudinal optical conductivity inthe most general nonlinear-dirty case can be expressed as

σxx(ω) =gsgv

~ω(2π)d

∫dk|Mvc

x |2nk=m

1

ωk − ω + iγ2

.

(22)We emphasize here that the non-linearity of the opti-cal conductivity in Eq. (22), stems from the nk term,whose solution is obtained from the optical Bloch equa-tion within RWA.

Let us now consider the following limiting cases inwhich Eq. (22) simplifies. The limiting case for γ2/ω 1(γ2/ω ≥ 1) corresponds to the clean (dirty) limit, and thelimiting case for ζ 1 (ζ ≥ 1) is related to the linear(non-linear) response of the system.

A. Linear response in the clean limit: ζ 1, andγ2/ω 1

In this limit, to zeroth order in ζ, we have nk → neqk ,

and converting the Lorentzian into a Dirac-delta func-tion, we have

σlcxx(ω) =

−πgsgv~ω(2π)d

∫dk|Mvc

x |2δ(ωk − ω)(fck − fvk) .

(23)Note that the conductivity obtained above [Eq. (23)], isidentical to that obtained from the Kubo formalism.

For systems with particle-hole symmetry and isotropicquasi-particle dispersion, such as graphene and massivegraphene, Eq. (23) can be expressed as

σlcxx(ω) =

πgsgvg(ω, α, T )

~ω(2π)d

∫dk|Mvc

x |2δ(ωk − ω) , (24)

where α ≡ maxµ,∆, with ∆ being half of the band-gapin a given semiconductor. The function

g(ω, α, T ) ≡ 1

2

[tanh

(~ω + 2α

4kBT

)+ tanh

(~ω − 2α

4kBT

)].

(25)In the zero temperature limit, g(ω, α, T → 0) =Θ(~ω/2 − |α|), where Θ(x) denotes the Heaviside stepfunction.

B. Linear response in the dirty limit: ζ 1, andγ2/ω ≥ 1

As in the previous case, here again we can approximatenk → neq

k upto zeroth order in ζ. However in this casethe Lorentzian has to be retained in the integral. Thecorresponding conductivity is given as

σldxx(ω) =

−gsgv~ω(2π)d

∫dk|Mvc

x |2γ2(fck − fvk)

(ωk − ω)2 + γ22

. (26)

C. Non-linear response in the clean limit: ζ ≥ 1,and γ2/ω 1

Here the Lorentzian can be approximated by a deltafunction, and from Eq. (22) one obtains

σncxx(ω) =

−πgsgv~ω(2π)d

∫dk|Mvc

x |2δ(ωk − ω)(fck − fvk)

1 + |Mvcx |2ζ2/(e2v2

F).

(27)For systems with particle-hole symmetry and isotropicquasi-particle dispersion, such as graphene and massivegraphene, Eq. (23) can be approximated as

σncxx =

πgsgvg(ω, α, T )

~ω(2π)d

∫dk|Mvc

x |2δ(ωk − ω)

1 + ζ2|Mvcx |2/(e2v2

F),

(28)where g(ω, α, T ) is defined in Eq. (25).

Below, we will explore the optical conductivity ofdoped and gapped graphene in all the four regimes. Notethat the transverse (Hall like) conductivity, σyx(ω) willalso have expressions similar to that of Eqs. (22)-(26),with the substitution |Mvc

x |2 →Mvcx M

cvy in the numera-

tor.Here we would like to emphasize that the formal-

ism described above gives only the finite frequency partof the conductivity which cannot be extrapolated tothe DC limit (limitation imposed due to RWA). Thefull paramagnetic conductivity, which includes the zerofrequency Drude weight (D) is given by σtotal(ω) =πDδ(ω) + σ(ω). The Drude weight is explicitly given byD = limω→0 ω=m[σ(ω)] (see Ref. [59] for details). Theimaginary part of the optical conductivity can thereforebe evaluated by making use of the Kramers-Kronig rela-tions, as

=mσ(ω) =2

πωP∫ ∞

0

dω′ω′2<eσ(ω′)

ω2 − ω′2, (29)

![Page 6: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/6.jpg)

6

where P denotes the principal part of the integral.Experimentally the optical conductivity is probed via

the differential optical transmission or reflection spec-troscopy. Motivated by this, in the next Section, weexplore the effect of non-linearity on the reflection andtransmission spectrum.

IV. NON-LINEAR DIFFERENTIALTRANSMISSIVITY AND REFLECTIVITY FOR

2D MATERIALS

The calculated non-linear conductivity has significantimplications for optical experiments. In this section wedetermine the differential transmission (or equivalentlythe reflection coefficient) of a ‘free standing’ two dimen-sional material, suspended in vacuum.

Let us consider a linearly polarized incident field prop-agating normal to the plane of the 2D material. For def-initeness, let us assume that the two-dimensional sampleis freely suspended in the x − y plane at z = 0. An in-coming field directed along the negative z-direction canbe decomposed into its components as,

E =

EI sin(ωt+ qz) + ER sin(ωt− qz) , z > 0ET sin(ωt+ qz) , z < 0,

(30)where q = ω/c is the photon momentum and Ei =(E0i cos θ0, E0i sin θ0), with i = I,R and T , denoting theincident, reflected and the transmitted components. θ0

is the polarization angle with respect to the x-axis. In-teraction of the incident light with the carriers in the 2Dsample, is modeled in the Maxwell’s equations, via thetotal current density in the 2D (x − y) plane, having avanishing thickness. This implies J(t) ≡ J(t)δ(z). Thespatiotemporal evolution of the x component of the elec-tromagnetic field is given by

∇2Ex − µ0ε0∂2Ex

∂t2= µ0∂tJxδ(z) . (31)

Integrating the above equation across the two dimen-sional plane yields

∂zEx|z=0+ − ∂zEx|z=0− = µ0∂tJx . (32)

Substituting Eq. (30) in Eq. (32), we obtain

(EI − ER − ET ) cos θ0 =cµ0

ω cos(ωt)∂tJx . (33)

Additionally, the continuity of the electromagnetic fieldacross the 2D layer yields,

EI + ER = ET . (34)

Furthermore, if we assume the material to be isotropic,with a conductivity tensor which has only diagonal ele-ments, we have Jx = σxx sin(ωt)[ωET cos(θ0)]. With this

the non-linear transmissivity can be easily obtained tobe,

T (ω) ≡∣∣∣∣ETEI

∣∣∣∣2 =

[1 +

παfine

2

σxx(ω)

σ0

]−2

, (35)

where αfine ≡ e2/(4π~cε0) is the universal fine structureconstant and σ0 ≡ e2/(4~), is the so called universalac conductivity of graphene. Here σxx(ω) is the non-linear longitudinal conductivity. The reflectivity R(ω) =|ER/EI |2, can also be obtained in a similar fashion andit is given as

R(ω) =

(παfine

2

σxx(ω)

σ0

)2 [1 +

παfine

2

σxx(ω)

σ0

]−2

.

(36)The absorption coefficient is given by α(ω) ≡ 1−T (ω)−R(ω) and it denotes the fraction of light intensity which iseither scattered by the surface atoms of the 2D material(Rayleigh scattering) or absorbed.

V. NONLINEAR CONDUCTIVITY OF DOPEDGRAPHENE

In this section we apply the general framework devel-oped in Sec. II and Sec. III to calculate the non-linear op-tical conductivity of graphene. For simplicity, we use theeffective low energy quasiparticle dispersion of grapheneinstead of the full tight-binding Hamiltonian. The cor-rections to the low energy dispersion on the universalconductivity has been shown to be ∼ ~ω/(72 × 2.8eV)[20]. Thus such effects can be safely neglected forall frequencies in the optical domain and below. Forgraphene, we have εck = −εvk = ~vFk, and Mvc =

Mcv∗ = ievFτsinφk,− cosφk where k = (k2x + k2

y)1/2,

φk = tan−1(ky/kx) and τ = +1 (−1) for the K (K ′)valley.

We now consider the non-linear optical conductivity ofgraphene arising from the inter-band transitions in var-ious regimes. We start with the linear response in theclean limit of graphene, i.e., for ζ 1 and γ2/ω 1limit. In this regime, using Eq. (24), one can obtain thefinite temperature optical conductivity for graphene as

σlcxx(ω) =

gsgve2

16~g(ω, µ, T ) . (37)

This has also been derived earlier from the Kubo for-malism (see Eq. (25) of Ref. [20]). In Eq. (37), gs = 2(gv = 2) denotes the spin (valley) degree of freedomin graphene and the function g(ω, µ, T ) is defined inEq. (25). In the limiting case of T → 0, including thespin and valley degeneracy factors, Eq. (37) reduces to,

σlcxx(ω) =

e2

4~Θ

(~ω2− |µ|

), (38)

which has a finite universal value as long as the opticalexcitation energy is greater than twice the chemical po-tential. Equation (38) yields the so called ‘universal’ ac

![Page 7: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/7.jpg)

7

12 13 14 15

log10(!)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8lo

g 10(E

0)

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

12 13 14 15

log10(!)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

log 1

0(E

0)

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

(a) (b)

ld

nd nc

lc

12 13 14 15log10(!)

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

/

0

E0 = 102 V/m

E0 = 104 V/m

E0 = 106 V/m

2 3 4 5 6 7 8log10(E0)

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

/

0

! = 1012 Hz

! = 1014 Hz

! = 1015 Hz

(c) (d)

FIG. 3. Color plot of the nonlinear (inter-band) optical con-ductivity (in units of σ0 = e2/4~) as a function of frequencyand the electric field strength of the incident laser beam for(a) pristine graphene with µ = 0 and (b) doped graphenewith µ = 0.1 eV (or equivalently µ/~ = 1.5 × 1014 Hz). Thevertical (white) line represents ω = γ2, which is the boundaryof the clean (also called collision-less or high frequency limitfor ω ≥ γ2) and the dirty (or collisional or low frequency)limit. The dashed white line marks the boundary of the linear-nonlinear response regime [ζ ≡ evFE0/(~ω

√γ1γ2) = 1], and

together with the boundary of the clean limit, it divides theplot into 4 regimes, linear clean (marked ‘lc’), non-linear clean(‘nc’), non-linear dirty (‘nd’) and linear dirty (‘ld’). Panel (c)shows horizontal cuts from the upper two panels, i.e., the con-ductivity as a function of ω for different electric field strengthsfor both, the µ = 0 case (solid lines), and the doped case ofµ = 0.1 eV (dotted lines of the same color). The yellow circlesshow the excellent match of Eq. (41), in the linear dirty limit,with the exact numerical results. Panel (d) displays verticalcuts from the upper two panels, i.e., the conductivity as afunction of E0 for different frequencies with solid lines for theµ = 0, and the dotted lines of the same color for µ = 0.1eV .Here the yellow circles show the excellent match of Eq. (39),in the non-linear clean limit, with the exact numerical re-sults. In all the panels we have chosen vF = 106 m/s, andγ1, γ2 = 1012, 1014 Hz.

conductivity of graphene which was predicted in Refs. [15and 17], and experimentally observed in Ref. [6].

In the non-linear and clean limit, we have ζ ≥ 1 andγ2/ω 1. Using Eq. (28), the optical conductivity forgraphene takes the form

σncxx(ω) =

e2

4~2

ζ2

(1− 1

(1 + ζ2)1/2

)g(ω, µ, T ) . (39)

As a consistency check we note that Eq. (39) reduces toEq. (37) in the limiting case of ζ → 0. Note that forthe specific case of pristine graphene (µ = 0 at zero tem-perature), Eq. (39) can also be derived by following thewave-function based approach and integrating Eq. (12)of Ref. [29].

2 4 6 8log10(E0)

0.96

0.98

1.00

T(E

0)

! = 1012 Hz

! = 1014 Hz

! = 1015 Hz

(a)

(b)

12 13 14 15

log10(!)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

log 1

0(E

0)

0.98

0.99

1.00

12 13 14 15

log10(!)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

log 1

0(E

0)

0.98

0.99

1.00(a) (b)

12 13 14 15log10(!)

0.97

0.98

0.99

1.00

T(!

)

E0 = 102 V/m

E0 = 104 V/m

E0 = 106 V/m

(c)

(d)

FIG. 4. Color plot of the nonlinear transmission as a functionof frequency and the electric field strength of the incidentlaser beam for (a) pristine graphene with µ = 0 and (b) dopedgraphene with µ = 0.1 eV (or equivalently µ/~ = 1.5 × 1014

Hz). Panels (c) and (d) display horizontal and vertical cuts,respectively with the solid lines corresponding to the µ = 0case, and the dotted lines representing the µ = 0.1 eV. Otherparameters are identical to that of Fig. 3.

Next we consider the linear response in the dirty limitfor which ζ 1 and γ2/ω ≥ 1. In this case the form ofconductivity changes substantially and at zero tempera-ture it is

σldxx(ω) =

e2γ2

4π~ω

∫ 2Λ~

2|µ|~

dωk

[ωk

(ωk − ω)2 + γ22

− (ω → 0)

],

(40)where Λ is the ultraviolet energy cutoff, which physicallyshould correspond to half of the bandwidth. In a tight-binding model of graphene half of the bandwidth is 3×2.8eV.

Evaluating Eq. (40) we obtain

σldxx(ω) =

e2

4π~[f (ω, 2Λ/~)− f (ω, 2|µ|/~)] , (41)

where

f(ω, x) ≡ tan−1

(x− ωγ2

)+γ2

2ωln

[γ2

2 + (ω − x)2

γ22 + x2

].

(42)The finite temperature generalization of Eq. (41) has tobe calculated numerically. As a consistency check we notethat Eq. (41) reduces to Eq. (38) in the limit γ2 ω.

For the most general case of the nonlinear-dirtyregime, starting with Eq. (20), we express the dissi-pative part of the steady state current for each spinand valley of graphene (x and y components) as Jk =

Jk (sinφk,− cosφk) . Here,

Jk =e2v2

FE0 sin(φk − θ0)γ1γ2neqk

~ωγ1 [(ωk − ω)2 + γ2

2 ] + γ2|Ωvc|2 , (43)

![Page 8: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/8.jpg)

8

and θ0 is the polarization angle of the linearly polarizedfield, with respect to the x axis. We then have the to-tal longitudinal conductivity for graphene as σxx(ω) =(2π)−2gsgv

∫dk σ′xx(k), where

ωσ′xx(k) =e2

~v2

Fγ2(fck − fvk) sin2 φk[(ωk − ω)2 + γ2

2(1 + ζ2 sin2 φk)]−(ω → 0).

(44)At T → 0, the k-integral of Eq. (44) has lower and up-per limits of 2|µ|/~vF and 2Λ/~vF respectively. It cantherefore be evaluated exactly (as in Eq. (40)) to obtain,

σxx(ω) =e2

4π2~

∫ 2π

0

dφk sin2 φk [f1(2Λ/~)− f1(2|µ|/~)] ,

(45)where,

f1(ω, x) ≡ γ2

γφk

tan−1

(x− ωγφk

)+γ2

2ωln

[γ2φk

+ (ω − x)2

γ2φk

+ x2

],

(46)and γφk

= γ2(1 + ζ2 sin2 φk)1/2. The φk integral inEq. (45), can also be done analytically, yielding a cum-bersome expression without much insight. However, it iseasy to check that in the linear response regime, ζ → 0,γφk→ γ2, and Eq. (45), reduces to Eq. (41), as expected.

The optical conductivity of graphene, in all fourregimes is shown in Fig. 3. The ζ = 1 line clearlymarks the boundary of the non-linear response regime,with saturation effects dominating on the ζ > 1 side.Interestingly enough, the ‘universal’ optical conductivityof graphene σ0 = e2/(4~), seems to be valid only in theω > γ2 and ζ 1 regime. Figure 3 also suggests thatnon-linear optical saturation effects will become domi-nant with decreasing optical frequencies while keepingthe laser intensity constant. The effect of non-linear op-tical conductivity on the transmission spectrum is high-lighted in Fig. 4.

An interesting observation from Eq. (43), is that theoff-diagonal conductivity σyx(ω) (for a x polarized field)vanishes for graphene. This is on account of the φk in-tegration vanishing for each valley. This is not the casefor massive graphene where σyx(ω) is finite for each val-ley with opposite signs for the two valleys. Thereforethe total σyx(ω) cancels out. This implies that one canpossibly have a finite σyx in massive graphene if the twovalleys can be made to have a different bandgap.

VI. NONLINEAR OPTICAL CONDUCTIVITYOF GAPPED GRAPHENE

We now proceed to discuss the case of gappedgraphene. If a gap, ∆ is introduced in the band struc-ture of graphene, say by growing it epitaxially on topof SiC [63 and 64], then the effective Hamiltonian wouldtake the form of Eq. (4), with h0k = 0, h1k = ~vFkx,h2k = ~vFky, and h3k = ∆. In this case, we have

12 13 14 15

log10(!)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

log 1

0(E

0)

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

12 13 14 15

log10(!)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

log 1

0(E

0)

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

(d)(c)

(a) (b)

ld

nd nc

lc

2 3 4 5 6 7 8log10(E0)

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

/

0

! = 1012 Hz

! = 1014 Hz

! = 1015 Hz

12 13 14 15log10(!)

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

/

0

E0 = 102 V/m

E0 = 104 V/m

E0 = 106 V/m

(c)

(d)

FIG. 5. Color plot of the optical conductivity as a function offrequency and the electric field strength of the incident laserbeam for (a) gapped graphene (∆ = 0.065eV = ~× 1014 Hz)with µ = 0 and (b) gapped and doped graphene with µ = 2∆.As in the case of graphene, the vertical solid white line at ω =γ2, and the dashed white line for ζ ≡ evFEI/(~ω

√γ1γ2) =

1] divide the parameter space into 4 regimes: linear clean(marked ’lc’), non-linear clean (’nc’), non-linear dirty (’nd’)and linear dirty (’ld’). Panel (c) show horizontal cuts from theupper two panels, i.e., the conductivity as a function of ω fordifferent electric field strengths for both, the µ = 0 case (solidlines), and the doped case of µ = 0.13 eV (dotted lines of thesame color). The yellow circles show the excellent match ofEq. (51), in the linear dirty limit, with the exact numericalresults. Panel (d) displays vertical cuts from the upper twopanels, i.e., the conductivity as a function of EI for differentfrequencies with solid lines for the µ = 0, and the dotted linesof the same color for µ = 0.13 eV. Here the yellow circlesshow the excellent match of Eq. (50), in the non-linear cleanlimit, with the exact numerical results. In all the panels wehave chosen vF = 106 m/s, and γ1, γ2 = 1012, 1014 Hz.

εck = −εvk ≡ gk = (~2v2Fk

2 +∆2)1/2. The x and y compo-nents of the inter-band optical matrix element are givenby

Mvc

evF= −

(∆ cosφk

gk− iτ sinφk,

∆ sinφkgk

+ iτ cosφk

),

(47)where τ = +1 (−1) for the K-valley (K ′-valley).

In the linear clean limit (ζ 1, γ2/ω 1), usingEq. (47) in Eq. (23), we obtain the optical conductivityfor massive graphene (with gs = gv = 2) to be

σlc,mxx (ω) =

gsgve2

16~

[1 +

4∆2

~2ω2

]g(ω,max(|µ|,∆), T ),

(48)where function g(x) is defined in Eq. (25). In the limiting

![Page 9: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/9.jpg)

9

case of T → 0, g(x)→ Θ(x) and

σlc,mxx (ω) =

e2

4~

[1 +

4∆2

~2ω2

]Θ

(~ω2−max(|µ|,∆)

).

(49)The above expression clearly suggests that the chemicalpotential is not important if it lies inside the gap (µ < ∆).This is a direct consequence of unavailability of any phasespace below the bandgap for optical excitations. Evi-dently in the ∆→ 0 limit, we recover the correspondingoptical conductivity expression for graphene.

In the nonlinear clean limit (ζ ≥ 1 and γ2/ω 1),we use Eq. (28) to calculate the optical conductivity atfinite temperature. For massive Dirac systems in twodimensions, we obtain,

σnc,mxx =

e2g(ω, α, T )

2~ζ2

[1− 1√

1 + ζ2

(1 +

4∆2ζ2

~2ω2

)−1/2].

(50)In the limiting case of ∆→ 0, Eq. (50) reduces to Eq. (39)as expected.

Next we consider the linear dirty limit (ζ 1 andγ2/ω ≥ 1) and with the help of Eq. (26), we arrive at thefollowing expression in the T → 0 limit,

σld,mxx =

e2γ2

4π~ω

∫ 2Λ~

2α~

dωk

[4~−2∆2 + ω2

k

ωk [(ωk − ω)2 + γ22 ]− (ω → 0)

],

(51)

where Λ is the ultraviolet energy cutoff and α =max|µ|,∆. Evaluating Eq. (51) we obtain

σld,mxx (ω) =

e2

4π~[f2 (ω, 2Λ/~)− f2 (ω, 2α/~)] , (52)

where we have defined,

f2(ω, x) ≡ (1 + y) tan−1

(x− ωγ2

)− γ2

2 − 4~−2∆2

2γ2ωln[x2 + γ2

2 ]

+γ2(1− y)

2ωlog[(x− ω)2 + γ2

2 ]− ωy

γ2log(x) ,

(53)

and y ≡ 4~−2∆2/(ω2 + γ22). The finite temperature gen-

eralization of Eq. (52) has to be calculated numerically.As a simple check we note that as ∆ → 0, Eq. (52) re-duces to Eq. (41).

In the most general case, corresponding to the nonlin-ear dirty limit for massive graphene, the dissipative partof the current density which arises only from the inter-band contribution, is given by Jm

k = (Ak, Bk)neqk , where

Ak =e2v2

FE0γ1

[∆2γ2 cos θ0 + ~2v2

Fk2γ2 sin(φk − θ0) sinφk − τ∆gk(ωk − ω) sin θ0

]~ωg2

k γ1 [(ωk − ω)2 + γ22 ] + γ2|Ωcvk |2

, (54)

Bk =e2v2

FE0γ1

[τ∆gk(ωk − ω) cos θ0 − ~2v2

Fk2γ2 sin(φk − θ0) cosφk + ∆2γ2 sin θ0

]~ωg2

k γ1 [(ωk − ω)2 + γ22k] + γ2|Ωcvk |2

. (55)

However for this case, the k integration of Eq.(54) has tobe done numerically.

The optical conductivity of massive graphene, in allfour regimes is shown in Fig. 5. As in the case ofgraphene, the ζ = 1 line marks the boundary of thenon-linear response regime, saturable absorption effectsdominating beyond ζ > 1. Note that the Kubo for-mula based result for the optical conductivity of massivegraphene [Eq. (48)], is valid only in the ω > γ2 and ζ 1regime. The impact of non-linear optical conductivity onthe transmission spectrum is highlighted in Fig. 6.

Finally we note that in graphene σyx(ω) was zero for ax polarized light for each valley. This is not the case formassive graphene. We find that based on Eq. (55), for ax polarized light, each valley has a finite σyx(ω), which

in the clean linear response regime is given by

σyx(ω) =2σ0

π

∑τ

τ∆τ

~ωlog

(2 max∆τ , µ

2 max∆τ , µ − ω

),

(56)where τ = +1 (−1) corresponds to the K (K ′) valley and∆τ is the corresponding gap. Note that in Eq. (56) thesign of σyx(ω) in the K valley turns out to be opposite tothat of the K ′ valley and if they have the same gap, thetotal σyx(ω) vanishes. However, if a valley asymmetrycan be induced in graphene or other Dirac material (bybreaking time reversal symmetry) [65], leading to differ-ent band gap at the K and K ′ valleys (∆K 6= ∆K′), thenwe can have a finite σyx(ω).

![Page 10: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/10.jpg)

10

(a)

(b)

(a) (b)

12 13 14 15log10(!)

0.97

0.98

0.99

1.00

T(!

)

E0 = 102 V/m

E0 = 104 V/m

E0 = 106 V/m

2 3 4 5 6 7 8log10(E0)

0.96

0.98

1.00

T(E

0)

! = 1012 Hz

! = 1014 Hz

! = 1015 Hz

12 13 14 15

log10(!)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8lo

g 10(E

0)

0.98

0.99

1.00

12 13 14 15

log10(!)

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

log 1

0(E

0)

0.98

0.99

1.00(a) (b)

(c)

(d)

FIG. 6. Color plot of the nonlinear transmission as a functionof frequency and the electric field strength of the incidentlaser beam for (a) pristine graphene with µ = 0 and (b) dopedgraphene with µ = 0.13 eV (or equivalently µ/~ = 2 × 1014

Hz). Panels (c) and (d) display horizontal and vertical cuts,respectively with the solid lines corresponding to the µ = 0case, and the dotted lines representing the µ = 0.13 eV. Otherparameters are identical to that of Fig. 5.

VII. CONCLUSION

In this paper, we have present a unified formulationto calculate the non-linear optical conductivity for ageneric two band system. Our model is based on asteady state solution of the optical-Bloch equations whichyields an analytic expression for the population inver-sion and the inter-band coherence. A natural outcomeof our model is the appearance of the dimensionless pa-

rameter ζ ∝ E0/ω, which quantifies the degree of opti-cal non-linearity in the system, which was first pointedout by Mishchenko in the context of graphene [29]. Thisimplies that nonlinear saturation effects are stronger atlower frequencies for the same strength of the optical fieldstrength. Furthermore, based on the parameter ζ andthe coherence decay rate γ2, any optical two band sys-tem can be said to be in one of the four regimes: (1)linear clean where ζ 1, and γ2 ω, (2) linear dirtywhere ζ 1, and γ2 ≥ ω, (3) non-linear clean whereζ ≥ 1, and γ2 ω, and (4) non-linear dirty where ζ ≥ 1,and γ2 ≥ ω. These regimes present distinct signaturesin the optical conductivity and the optical transmissionand reflection spectrum.

Having established a general formulation for any twoband system, we explicitly study the non-linear opticalconductivity of graphene and massive graphene using theeffective low energy Hamiltonian, and find analytic ex-pressions for the optical conductivity in various regimes,reproducing the results for the clean case in the linear re-sponse regime. We emphasize that the usually reportedKubo formula based results for the optical conductivityare generally valid only in the high frequency (ω γ2)and linear response (ζ 1) regimes.

An obvious extension of this work is to include theelectron-phonon and electron-electron interactions ex-plicitly along with the optical Bloch equation. This willprovide a natural microscopic model for population in-version and decoherence decay rates, γ1 and γ2, whichwe have assumed to be constant in this paper. Alongwith this the effect of band bending, trigonal warping etc.can be included by considering a tight-binding model forthe Hamiltonian as opposed to an effective low energyHamiltonian, and that will also increase the validity ofthis formulation for a wide range of optical frequencies.

∗ [email protected] K. S. Novoselov, A. K. Geim, S. V. Morozov, D. Jiang,

Y. Zhang, S. V. Dubonos, I. V. Grigorieva, and A. A.Firsov, “Electric field effect in atomically thin carbonfilms,” Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

2 K. S. Novoselov, A. K. Geim, S. V. Morozov, D. Jiang,M. I. Katsnelson, I. V. Grigorieva, S. V. Dubonos, andA. A. Firsov, “Two-dimensional gas of massless diracfermions in graphene,” Nature 438, 197–200 (2005).

3 A. K. Geim and K. S. Novoselov, “The rise of graphene,”Nat Mater 6, 183–191 (2007).

4 M. I. Katsnelson, Graphene: Carbon in Two Dimensions(Cambridge University Press, 2012).

5 Jahan M. Dawlaty, Shriram Shivaraman, Jared Strait,Paul George, Mvs Chandrashekhar, Farhan Rana,Michael G. Spencer, Dmitry Veksler, and Yunqing Chen,“Measurement of the optical absorption spectra of epitax-ial graphene from terahertz to visible,” Applied PhysicsLetters 93, 131905 (2008).

6 R. R. Nair, P. Blake, A. N. Grigorenko, K. S. Novoselov,

T. J. Booth, T. Stauber, N. M. R. Peres, and A. K.Geim, “Fine structure constant defines visual transparencyof graphene,” Science 320, 1308 (2008).

7 A. B. Kuzmenko, E. van Heumen, F. Carbone, andD. van der Marel, “Universal optical conductance ofgraphite,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 117401 (2008).

8 Z. Q. Li, E. A. Henriksen, Z. Jiang, Z. Hao, M. C. Martin,P. Kim, H. L. Stormer, and D. N. Basov, “Dirac chargedynamics in graphene by infrared spectroscopy,” Nat Phys4, 532–535 (2008).

9 Kin Fai Mak, Matthew Y. Sfeir, James A. Misewich,and Tony F. Heinz, “The evolution of electronic structurein few-layer graphene revealed by optical spectroscopy,”PNAS 107, 14999–15004 (2010).

10 K. I. Bolotin, K. J. Sikes, Z. Jiang, M. Klima, G. Fu-denberg, J. Hone, P. Kim, and H. L. Stormer, “Ultra-high electron mobility in suspended graphene,” Solid StateCommunications 146, 351 – 355 (2008).

11 N. Stander, B. Huard, and D. Goldhaber-Gordon, “Evi-dence for klein tunneling in graphene p-n junctions,” Phys.

![Page 11: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/11.jpg)

11

Rev. Lett. 102, 026807 (2009).12 F. V. Tikhonenko, D. W. Horsell, R. V. Gorbachev, and

A. K. Savchenko, “Weak localization in graphene flakes,”Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 056802 (2008).

13 K. S. Novoselov, Z. Jiang, Y. Zhang, S. V. Morozov, H. L.Stormer, U. Zeitler, J. C. Maan, G. S. Boebinger, P. Kim,and A. K. Geim, “Room-temperature quantum hall effectin graphene,” Science 315, 1379 (2007).

14 Kirill I. Bolotin, Fereshte Ghahari, Michael D. Shulman,Horst L. Stormer, and Philip Kim, “Observation of thefractional quantum hall effect in graphene,” Nature 462,196–199 (2009).

15 Tsuneya Ando, Yisong Zheng, and Hidekatsu Suzuura,“Dynamical conductivity and zero-mode anomaly in hon-eycomb lattices,” Journal of the Physical Society of Japan71, 1318–1324 (2002).

16 V. P. Gusynin and S. G. Sharapov, “Transport of diracquasiparticles in graphene: Hall and optical conductivi-ties,” Phys. Rev. B 73, 245411 (2006).

17 V. P. Gusynin, S. G. Sharapov, and J. P. Carbotte,“Unusual microwave response of dirac quasiparticles ingraphene,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 256802 (2006).

18 V. P. Gusynin, S. G. Sharapov, and J. P. Carbotte, “Sumrules for the optical and hall conductivity in graphene,”Phys. Rev. B 75, 165407 (2007).

19 N. M. R. Peres, F. Guinea, and A. H. Castro Neto, “Elec-tronic properties of disordered two-dimensional carbon,”Phys. Rev. B 73, 125411 (2006).

20 T. Stauber, N. M. R. Peres, and A. K. Geim, “Opticalconductivity of graphene in the visible region of the spec-trum,” Phys. Rev. B 78, 085432 (2008).

21 Vitor M. Pereira, R. M. Ribeiro, N. M. R. Peres,and A. H. Castro Neto, “Optical properties of strainedgraphene,” EPL (Europhysics Letters) 92, 67001 (2010).

22 N. M. R. Peres, T. Stauber, and A. H. Castro Neto, “Theinfrared conductivity of graphene on top of silicon oxide,”EPL (Europhysics Letters) 84, 38002 (2008).

23 E. G. Mishchenko, “Effect of electron-electron interactionson the conductivity of clean graphene,” Phys. Rev. Lett.98, 216801 (2007).

24 Igor F. Herbut, Vladimir Juricic, and Oskar Vafek,“Coulomb interaction, ripples, and the minimal conduc-tivity of graphene,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 046403 (2008).

25 Lars Fritz, Jorg Schmalian, Markus Muller, and SubirSachdev, “Quantum critical transport in clean graphene,”Phys. Rev. B 78, 085416 (2008).

26 E. G. Mishchenko, “Minimal conductivity in graphene: In-teraction corrections and ultraviolet anomaly,” EPL (Eu-rophysics Letters) 83, 17005 (2008).

27 Zheshen Zhang and Paul L. Voss, “Full-band quantum-dynamical theory of saturation and four-wave mixing ingraphene,” Opt. Lett. 36, 4569–4571 (2011).

28 Z. Zhang and P. L. Voss, “A quantum-dynamical theory fornonlinear optical interactions in graphene,” ArXiv e-prints(2011), arXiv:1106.4838 [cond-mat.mes-hall].

29 E. G. Mishchenko, “Dynamic conductivity in graphenebeyond linear response,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 246802(2009).

30 S. A. Mikhailov, “Quantum theory of the third-order non-linear electrodynamic effects of graphene,” Phys. Rev. B93, 085403 (2016).

31 S. A. Mikhailov, “Non-linear electromagnetic response ofgraphene,” EPL (Europhysics Letters) 79, 27002 (2007).

32 M. I. Katsnelson, “Optical properties of graphene: The

fermi-liquid approach,” EPL (Europhysics Letters) 84,37001 (2008).

33 Kenichi L. Ishikawa, “Nonlinear optical response ofgraphene in time domain,” Phys. Rev. B 82, 201402 (2010).

34 S. A. Mikhailov and K. Ziegler, “Nonlinear electromag-netic response of graphene: frequency multiplication andthe self-consistent-field effects,” Journal of Physics: Con-densed Matter 20, 384204 (2008).

35 B. M. Ruvinskii and M. A. Ruvinskii, “On the nonlinear acconductivity in doped graphene,” Physics and chemistry ofsolid state 14, 703 (2013).

36 J. L. Cheng, N. Vermeulen, and J. E. Sipe, “Numeri-cal study of the optical nonlinearity of doped and gappedgraphene: From weak to strong field excitation,” Phys.Rev. B 92, 235307 (2015).

37 F. Bonaccorso, Z. Sun, T. Hasan, and A. C. Ferrari,“Graphene photonics and optoelectronics,” Nature Pho-tonics 4, 611–622 (2010).

38 Qiaoliang Bao and Kian Ping Loh, “Graphene photonics,plasmonics, and broadband optoelectronic devices,” ACSNano 6, 3677–3694 (2012).

39 P. Avouris and M. Freitag, “Graphene photonics, plasmon-ics, and optoelectronics,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topicsin Quantum Electronics 20, 72–83 (2014).

40 A. N. Grigorenko, M. Polini, and K. S. Novoselov,“Graphene plasmonics,” Nat Photon 6, 749–758 (2012).

41 Phaedon Avouris, “Graphene: Electronic and photonicproperties and devices,” Nano Letters 10, 4285–4294(2010).

42 S. A. Mikhailov, “Non-linear graphene optics for tera-hertz applications,” Microelectronics Journal 40, 712 – 715(2009), european Nano Systems (ENS 2007)InternationalConference on Superlattices, Nanostructures and Nanode-vices (ICSNN 2008).

43 Jesse J. Dean and Henry M. van Driel, “Second harmonicgeneration from graphene and graphitic films,” AppliedPhysics Letters 95, 261910 (2009).

44 M. M. Glazov, “Second harmonic generation in graphene,”JETP Letters 93, 366–371 (2011).

45 J. A. Crosse, Xiaodong Xu, Mark S. Sherwin, and R. B.Liu, “Theory of low-power ultra-broadband terahertz side-band generation in bi-layer graphene,” Nature Communi-cations 5, 4854 (2014).

46 E. Hendry, P. J. Hale, J. Moger, A. K. Savchenko, andS. A. Mikhailov, “Coherent nonlinear optical response ofgraphene,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 097401 (2010).

47 T. Gu, N. Petrone, J. F. McMillan, A. van der Zande,M. Yu, G. Q. Lo, D. L. Kwong, J. Hone, and C. W.Wong, “Regenerative oscillation and four-wave mixing ingraphene optoelectronics,” Nature Photonics 6, 554–559(2012).

48 Rui Wu, Yingli Zhang, Shichao Yan, Fei Bian, WenlongWang, Xuedong Bai, Xinghua Lu, Jimin Zhao, and EngeWang, “Purely coherent nonlinear optical response in so-lution dispersions of graphene sheets,” Nano Letters 11,5159–5164 (2011).

49 Saisai Chu, Shufeng Wang, and Qihuang Gong, “Ultra-fast third-order nonlinear optical properties of graphenein aqueous solution and polyvinyl alcohol film,” ChemicalPhysics Letters 523, 104 – 106 (2012).

50 M. V. Entin, L. I. Magarill, and D. L. Shepelyansky, “The-ory of resonant photon drag in monolayer graphene,” Phys.Rev. B 81, 165441 (2010).

51 J. Karch, C. Drexler, P. Olbrich, M. Fehrenbacher,

![Page 12: arXiv:1606.05072v1 [cond-mat.mes-hall] 16 Jun 2016 · Ashutosh Singh, 1Tuhina Satpati, Kirill I. Bolotin,2 Saikat Ghosh, and Amit Agarwal1, ... gauge, with the vector potential A](https://reader034.fdocuments.in/reader034/viewer/2022042411/5f29f38dca2bbc58545dcd82/html5/thumbnails/12.jpg)

12

M. Hirmer, M. M. Glazov, S. A. Tarasenko, E. L. Ivchenko,B. Birkner, J. Eroms, D. Weiss, R. Yakimova, S. Lara-Avila, S. Kubatkin, M. Ostler, T. Seyller, and S. D.Ganichev, “Terahertz radiation driven chiral edge currentsin graphene,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 276601 (2011).

52 J. Karch, P. Olbrich, M. Schmalzbauer, C. Zoth, C. Brin-steiner, M. Fehrenbacher, U. Wurstbauer, M. M. Glazov,S. A. Tarasenko, E. L. Ivchenko, D. Weiss, J. Eroms,R. Yakimova, S. Lara-Avila, S. Kubatkin, and S. D.Ganichev, “Dynamic hall effect driven by circularly po-larized light in a graphene layer,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 105,227402 (2010).

53 Ming Liu, Xiaobo Yin, Erick Ulin-Avila, Baisong Geng,Thomas Zentgraf, Long Ju, Feng Wang, and Xiang Zhang,“A graphene-based broadband optical modulator,” Nature474, 64–67 (2011).

54 Gerasimos Konstantatos, Michela Badioli, Louis Gau-dreau, Johann Osmond, Maria Bernechea, F. Pelayo Gar-cia de Arquer, Fabio Gatti, and Frank H. L. Koppens,“Hybrid graphene-quantum dot phototransistors with ul-trahigh gain,” Nature Nanotechnology 7, 363–368 (2012).

55 Weilu Gao, Jie Shu, Kimberly Reichel, Daniel V. Nickel,Xiaowei He, Gang Shi, Robert Vajtai, Pulickel M. Ajayan,Junichiro Kono, Daniel M. Mittleman, and QianfanXu, “High-contrast terahertz wave modulation by gatedgraphene enhanced by extraordinary transmission throughring apertures,” Nano Letters 14, 1242–1248 (2014).

56 F. H. L. Koppens, T. Mueller, Ph. Avouris, A. C. Fer-rari, M. S. Vitiello, and M. Polini, “Photodetectors basedon graphene, other two-dimensional materials and hybridsystems,” Nature Nanotechnology 9, 780–793 (2014).

57 Han Zhang, Dingyuan Tang, R. J. Knize, Luming Zhao,Qiaoliang Bao, and Kian Ping Loh, “Graphene mode

locked, wavelength-tunable, dissipative soliton fiber laser,”Applied Physics Letters 96, 111112 (2010).

58 M. T. Manzoni, I. Silveiro, F. J. Garcia de Abajo, andD. E. Chang, “Second-order quantum nonlinear opticalprocesses in single graphene nanostructures and arrays,”New Journal of Physics 17, 083031 (2015).

59 Tobias Stauber, Pablo San-Jose, and Luis Brey, “Opti-cal conductivity, drude weight and plasmons in twistedgraphene bilayers,” New Journal of Physics 15, 113050(2013).

60 T. Meier, P. Thomas, and S.W. Koch, Coherent Semi-conductor Optics: From Basic Concepts to NanostructureApplications (Springer, 2007).

61 Ermin Malic, Torben Winzer, Evgeny Bobkin, and An-dreas Knorr, “Microscopic theory of absorption and ultra-fast many-particle kinetics in graphene,” Phys. Rev. B 84,205406 (2011).

62 L. A. Falkovsky and A. A. Varlamov, “Space-time dis-persion of graphene conductivity,” The European PhysicalJournal B 56, 281–284 (2007).

63 S. Y. Zhou, G. H. Gweon, A. V. Fedorov, P. N. First,W. A. de Heer, D. H. Lee, F. Guinea, A. H. Castro Neto,and A. Lanzara, “Substrate-induced bandgap opening inepitaxial graphene,” Nature Materials 6, 770–775 (2007).

64 Eli Rotenberg, Aaron Bostwick, Taisuke Ohta, Jessica L.McChesney, Thomas Seyller, and Karsten Horn, “Originof the energy bandgap in epitaxial graphene,” Nature Ma-terials 7, 258–259 (2008).

65 B. Hunt, J. D. Sanchez-Yamagishi, A. F. Young,M. Yankowitz, B. J. LeRoy, K. Watanabe, T. Taniguchi,P. Moon, M. Koshino, P. Jarillo-Herrero, and R. C.Ashoori, “Massive dirac fermions and hofstadter butterflyin a van der waals heterostructure,” Science 340, 1427–1430 (2013).