ARTS & CULTURE SEPTEMBER 1 - Print...

Transcript of ARTS & CULTURE SEPTEMBER 1 - Print...

www.TheEpochTimes.com

11 SEPTEMBER 22–28, 2016 |ARTS & CULTURE

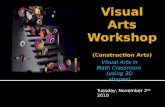

The Guide, 1883, by Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier (French, 1815–1891). Oil on canvas, 44 inches by 34 1/2 inches. Pri-vate collec-tion.

JOSLYN ART MUSEUM

shown a commitment to Russian music, recording many albums of arias and songs from his native country, as well as including them in his recitals.

Dmitri Hvorostovsky Sings of War, Peace, Love and Sorrow (on Delos), recorded last October, comprises scenes and arias from Russian ope-ras. He has performed some of these roles on stage, but not all of them. In fact, he is quoted in the liner notes as saying that he believes his coun-try’s operas are underrepresented on the world’s stages and he wants to use his position to remedy that.

The album captures the singer in fine voice with his usual dramatic flair.

Hvorostovsky had starred in Prokofiev’s War and Peace at the Met when the opera was first done there in 2002. The album begins with Svetlaje vesenneje neba (The radiance of the sky in spring). This is the first scene of the opera in which Prince Andrei overhears a late-night conversation between Natasha, with whom he falls in love, and her serv-ant, Sonya. While initially dejected,

upon hearing the young woman’s joy at encountering the beauty of nature, he declares that life is not over at age 31 and he still harbours hope for the future.

In Tchaikovsky’s 1884 Mazeppa, Hvorostovsky is again smitten by a young woman. This time, he is the title character, the 70-year-old military leader of a Ukrainian sep-aratist group. The opera is based on a rebellion that took place in the early 18th century and is still

timely in view of the current ten-sions between Russia and Ukraine.

The aria, though, has nothing to do with politics but is an expres-sion of Mazeppa’s love for Maria. Their wild passion has reinvigour-ated him in what he expected to be his declining years. Hvorostovsky has never appeared on stage in this opera. It was performed at the Met only when the Kirov Opera com-pany visited in 1998.

Tchaikovsky’s one-act opera Iolanta (1892) had its long overdue debut at the Met last season, star-ring the wonderful Anna Netrebko. Hvorostovky was not in the cast, but the CD contains a rapturous ren-dition of Robert’s aria in which the Duke sings of his love for Countess Mathilde. He raves about her intox-icating beauty even though he was supposed to have an arranged wed-ding with the blind Princess Iolanta.

Hvorostovsky has appeared on stage as Prince Eletzky in Tchaiko-vsky’s Queen of Spades, one of the composer’s two most frequently performed operas. (The other is Eugene Onegin.) Here, he takes on

excerpts as another character in the opera, Count Tomsky.

In Tomsky’s Ballad, he recounts the legend of the elderly Countess and the “three cards”, which sets the action leading to the downfall of the lead character, Herman. Tom-sky’s Song (If cute girls), is a light-hearted drinking song, with a cho-rus that urges the singer to deliver another witty verse.

The recording ends with the dra-matic final scene of Anton Rubin-stein’s The Demon (1871). Hvoros-tovsky plays the title character, who falls in love with a young woman named Tamara. The scene takes place at a convent to which Tamara had fled after the demon killed her bridegroom. She tries to resist him but cannot. After he kisses her, a chorus of angels appears and takes Tamara to heaven while making the demon disappear. Based on this excerpt, the opera seems to be unfairly neglected.

Hvorostovsky had appeared in a semi-staged version of The Demon in Moscow last year. For the record-ing, he has the same soprano,

Asmik Grigourian, sing the role of Tamara. She is also Natasha in the War and Peace scene. She is a rising star and deserves her own recital album. Incidentally, her late father, the tenor Gegam Grigourian, appeared with Hvorostovsky at the Met’s 2002 production of War and Peace.

The State Academic Symphony Orchestra of Russia and the Helikon Opera Chorus are expertly con-ducted by Hvorostovsky’s frequent collaborator Constantine Orbelian.

War, Peace, Love and Sorrow is another excellent example of Hvo-rostovsky’s art and a reminder of the beauty of Russian operas. The CD comes with translations of all the pieces.

Opera lovers should take note that Hvorostovsky will return to the Met next spring in Eugene Onegin with Anna Netrebko. They have each performed the opera here, but not together.

Barry Bassis has been a music, thea-tre+ and travel writer for over a dec-ade for various publications.

DELOS

dent that day. Although he tried to rec-oncile and bring the group back together after the schism took place, and believed he had handled the situation appropri-ately, he was depressed and upset by the whole experience to the point where he resigned from his position, giving up the power he had on this most impor-tant of boards.

The group then held their own annual salon, referred to as the Salon du Champ de Mars. This was not a group of Impres-sionists storming off to create their own organisation because their work was not accepted into the salon. The leader, Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, was a member of the institute and a traditional artist with tight paint handling and carefully organised and systematically designed compositions, as were most others who left the Société des Artistes Français dur-ing this legendary schism. It had nothing at all to do with Impressionists rebelling against the Academics, and everything to do with one group of Academics rebel-ling against an entrenched group of other Academics for totally different reasons.

According to William Bouguereau, Life and Works, by Damien Bartoli and Fred-eric Ross:

“The vote that occurred demon-strates that most of the participating artists believed that the main body had the goal of being fair-minded. ... Those who left to start their own organisation

were only a small per cent of the origi-nal body, and were clearly those who per-ceived their self-interest would be more likely supported in a new organisation where they as founders would have much more power.”

In truth, there was much finger-point-ing at the time in both directions, and two sides to the story, as there usually are. Both groups claimed to be helping young, unknown artists to show in the salon, but had different ideas of how best to accomplish this.

Meissonier, the leader of the dissenters, was the antithesis of the Avant-Garde. He was principally known as a military painter with incredibly detailed work. He did large canvases, but also is well known for his cabinet-sized paintings, which included 17th- and 18th-century cavaliers. He used such small and pre-cise brushstrokes that one needs a mag-nifying glass to fully appreciate them. In this sense, he is somewhat reminiscent of 17th-century Dutch masters like Gerrit Dou, Frans van Mieris and Jan Vermeer.

Kara Lysandra Ross, the chief operating officer for the Art Renewal Centre (ArtRe-newal.org), is an expert in 19th-century European painting.

Read the whole series here: ept.ms/Aca-demicArt

Meissonier’s painting The Guide

exemplifies his passions for French military historical sub-ject matter. Depicting a large group of soldiers on horse-back, proud and confident,

the soldiers in the lead look at the guide with some disdain,

their swords drawn.

At the time depicted, it was advised by French military

theorist Colonel de Brack that post-revolutionary cavalry tie their local guide to a soldier’s saddle in case he tried to run, with a sword at the ready as a reminder of what would hap-pen if he made an attempt. Meissonier depicts the guide in this picture to be outwardly indifferent to his situation, walking with focused intent

and a pipe in hand.

The microscopic details in this painting are something that Meissonier was known for,

from the individual faces and expressions of the soldiers, to the buttons and buckles

on the soldiers’ uniforms. The moody autumn landscape

helps the viewer imagine what it must have been like for both

the guide and soldiers.

COURTESY OF ART RENEWAL CENTRECOURTESY OF ART RENEWAL CENTRE

Le Print-emps, 1886,

by William Bouguereau

(French, 1825–1905).

Oil on canvas, 84 5/8 inches by 46 inches.

Dmitri Hvorostovsky has a distinctive voice, which he uses with musicality and extraordinary breath control.